Cryptitis

Cryptitis is an inflammation of the crypts of Morgagni or anal semilunar valves 1. Two centimeters from the anal orifice (anus) the lining tissue of the anus begins to change into the specialized lining of the colon. This junction is called the pectinate line. At the pectinate line are small mounds of tissue that protrude into the anal canal. Between these protrusions into the anus are small out-pouchings from the anus and into the surrounding tissues. These out-pouchings are the anal crypts. Although they are covered with flaps of anal lining tissue, the anal crypts communicate with the anus and colon above. Inflammation of the crypts, probably caused by the trauma of passing stool and/or infection, is referred to as cryptitis. If infection progresses, it can extend further into the surrounding tissues and lead to the formation of an abscess or fistula. Papillitis, fissure-in-ano, internal hemorrhoids, blind internal fistula and proctitis, may be associated with cryptitis. Cryptitis is associated with repetitive sphincter trauma from spasm, recurrent diarrhea, or passage of large/hard stools.

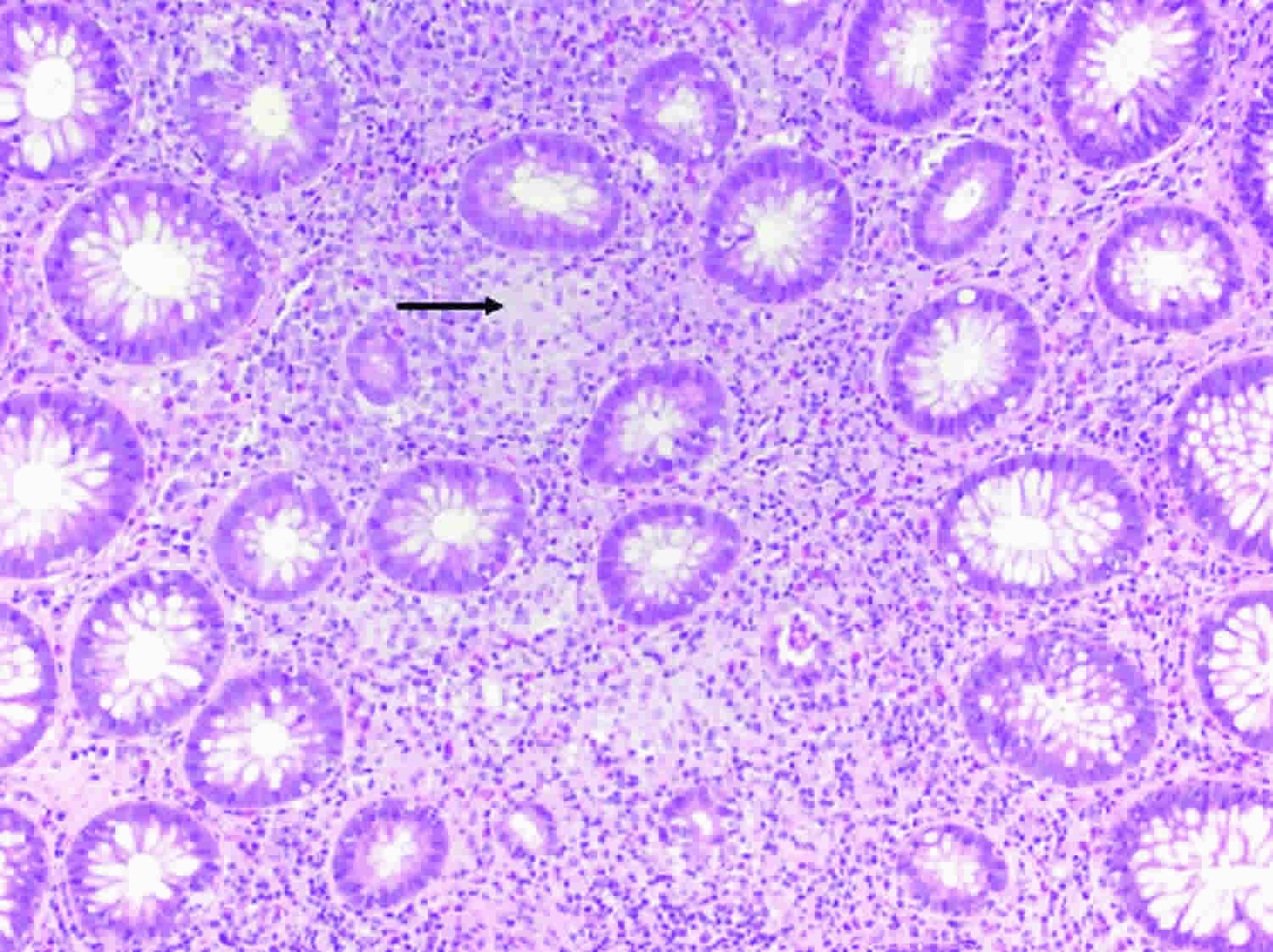

Cryptitis is also a term that is used to describe one of the abnormalities that is seen under the microscope when small intestinal or colonic tissue is examined. The intestinal crypts are tubular structures composed of cells that protrude from the inner lining of the intestines and into the walls of the intestines. These crypts contain the cells that give rise to all the other cells that move out of the crypts and eventually line the inner lining of the intestines. Inflammation of the crypts is known as cryptitis. Cryptitis is seen in inflammatory bowel disease, both Crohn’s and Ulcerative Colitis, but it also can be seen in other inflammatory conditions of the intestines. It is not a disease itself but a histologic manifestation of several different diseases.

Cryptitis may be acute or chronic. In the acute form, the most important symptom is a constant sharp pain, increased on defecation, and becomes throbbing in character as pus forms. In the chronic forms, this sharp pain changes to a dull ache; attacks of itching also supervene.

Cryptitis diagnosis is made by the history, digital and instrumental examination.

Mild and uncomplicated cases of cryptitis may be satisfactorily treated in the office; when associated with other more important anorectal pathology, it is wiser to perform the whole operation in the hospital.

Surgical referral is indicated when:

- Infection has progressed and the crypt will not drain adequately on its own

- Surgical treatment is excision

Cryptitis causes

Cryptitis is a non-specific histopathologic finding that is seen in several conditions, e.g. inflammatory bowel disease 2, diverticular disease 3, radiation colitis 4 and infectious colitis.

Cryptitis is associated with repetitive sphincter trauma from spasm, recurrent diarrhea, or passage of large/hard stools.

Cryptitis pathophysiology

- Anal crypts are mucosal pockets that lie between the columns of Morgagnia. Formed by the puckering action of the sphincter muscles

- Superficial trauma (diarrhea, trauma from hard stool) → breakdown in mucosal lining

- Bacteria enter, inflammation extends into lymphoid tissue of the crypts / anal glands

- Can lead to anal fissure, anal fistula, perirectal abscesses

Cryptitis symptoms

- Anal pain

- Sphincter spasm

- Itching with or without bleeding

- Hypertrophied papillae

The most common symptoms of inflammatory bowel disease are belly pain and diarrhea. Other symptoms include:

- blood in the toilet, on toilet paper, or in the stool (poop)

- fever

- low energy

- weight loss

Inflammatory bowel disease can cause other problems, such as rashes, eye problems, joint pain and arthritis, and liver problems.

People with diverticulosis often have no symptoms, but they may have bloating and cramping in the lower part of the belly. Rarely, they may notice blood in their stool or on toilet paper.

Symptoms of diverticulitis are more severe and often start suddenly, but they may become worse over a few days. They include:

- Tenderness, usually in the left lower side of the abdomen

- Bloating or gas

- Fever and chills

- Nausea and vomiting

- Not feeling hungry and not eating

Infectious colitis

Colonic infection by bacteria, viruses, or parasites result in an inflammatory-type of diarrhea and account for the majority of cases presenting with acute diarrhea. These patients present with purulent, bloody, and mucoid loose bowel motions, fever, tenesmus, and abdominal pain. Common bacteria causing bacterial colitis include Campylobacter jejuni, Salmonella, Shigella, Escherichia coli, Yersinia enterocolitica, Clostridium difficile, and Mycobacterium tuberculosis. Common causes of viral colitis include Norovirus, Rotavirus, Adenovirus, and Cytomegalovirus. Parasitic infestation such as Entamoeba histolytica, a protozoan parasite, is capable of invading the colonic mucosa and causing colitis. Sexually transmitted infection affecting the rectum merit consideration during assessment. These diseases occur in patients with HIV infection and men who have sex with men and may include Neisseria gonorrhoeae, Chlamydia trachomatis, Herpes simplex, and Treponema pallidum.

The patients present with rectal symptoms that mimic inflammatory bowel disease, including rectal pain, tenesmus, bloody mucoid discharge, and urgency. Detailed medical history and identification of specific associated risks are essential in establishing the diagnosis. Stool microscopy and culture and endoscopy are crucial to the diagnosis. However, stool culture can help in the diagnosis of less than 50% of patients presenting with bacterial colitis, and endoscopic examinations usually reveal non-specific pathological changes. Therefore, an approach is needed to evaluate and diagnose the cause of colitis and exclude non-infectious causes. This activity discusses current strategies to diagnose and manage infectious colitis and how to make a high index of suspicion based on clinical presentation and use investigation methods to reach a final diagnosis. This activity discusses the etiology, epidemiology, pathophysiology, clinical presentation, evaluation, differential diagnosis, complications, and management of patients with infectious colitis.

Radiation colitis

Almost all patients undergoing radiation to the abdomen, pelvis, or rectum will show signs of acute radiation enteritis. Injuries clinically evident during the first course of radiation and up to 8 weeks later are considered acute 5. Chronic radiation enteritis may present months to years after the completion of therapy, or it may begin as acute enteritis and persist after the cessation of treatment. Only 5% to 15% of persons treated with radiation to the abdomen will develop chronic problems 6

Factors that influence the occurrence and severity of radiation enteritis include the following:

- Dose and fractionation.

- Tumor size and extent.

- Volume of normal bowel treated.

- Concomitant chemotherapy.

- Radiation intracavitary implants.

- Individual patient variables (e.g., previous abdominal or pelvic surgery, hypertension, diabetes mellitus, pelvic inflammatory disease, inadequate nutrition) 7.

In general, the higher the daily and total dose delivered to the normal bowel and the greater the volume of normal bowel treated, the greater the risk of radiation enteritis. In addition, the individual patient variables listed above can decrease vascular flow to the bowel wall and impair bowel motility, increasing the chance of radiation injury.

Ischemic colitis

Ischemic colitis occurs when blood flow to part of the large intestine (colon) is reduced, usually due to narrowed or blocked blood vessels (arteries). The diminished blood flow doesn’t provide enough oxygen for the cells in your digestive system. Ischemic colitis results in ischemic necrosis of varying severities that can range from superficial mucosal involvement to full-thickness transmural necrosis 8.

Ischemic colitis can cause pain and may damage your colon. Any part of the colon can be affected, but ischemic colitis usually causes pain on the left side of the belly area (abdomen). The classic presentation of ischemic colitis is an elderly patient presenting with bloody bowel movements, abdominal pain, and leukocytosis. Patients typically present with the acute onset of crampy abdominal pain and usually pass blood mixed with stool within 24 hours. The episode is usually preceded by an episode of transient hypoperfusion. The vasculature of the colon is thought to play an integral part in the disease.

Signs and symptoms of ischemic colitis can include:

- Pain, tenderness or cramping in your belly, which can occur suddenly or gradually

- Bright red or maroon blood in your stool or, at times, passage of blood alone without stool

- A feeling of urgency to move your bowels

- Diarrhea

- Nausea

The risk of severe complications is higher when you have symptoms on the right side of your abdomen. That’s because the arteries that feed the right side of your colon also feed part of your small intestine, so that area may also receive too little blood. Pain tends to be severe with this type of ischemic colitis.

Blocked blood flow to the small intestine can quickly lead to the death of intestinal tissue (necrosis). If this life-threatening situation occurs, you’ll need surgery to clear the blockage and to remove the portion of the intestine that has been damaged.

Ischemic colitis can be misdiagnosed because it can easily be confused with other digestive problems. You may need medication to treat ischemic colitis or prevent infection, or you may need surgery if your colon has been damaged. Sometimes, however, ischemic colitis heals on its own.

Bowel ischemia is mainly a disease of old age caused by atheroma of mesenteric vessels. Other causes include embolic disease, vasculitis, fibromuscular hyperplasia, aortic aneurysm, blunt abdominal trauma, disseminated intravascular coagulation, irradiation, and hypovolemic or endotoxic shock 9.

Occlusive mesenteric infarction (embolus or thrombosis) has a 90% mortality rate, whereas nonocclusive disease has a 10% mortality rate 10.

Venous infarction occurs in young patients, usually after abdominal surgery 11. Patients may present with colicky abdominal pain, which becomes continuous. It may be associated with vomiting, diarrhea, or rectal bleeding 12.

Cocaine-induced ischemic colitis is a recognized entity, and the diagnosis is based on clinical and endoscopic findings. Diagnostic imaging is helpful for evaluating abdominal symptoms, and previous studies have suggested specific sonographic findings in ischemic colitis 13.

A retrospective review compared the clinical features of 16 patients with ischemic colitis younger than 45 years with those older than 70 years. Constipation before the onset of symptoms was more frequently found in younger patients 14. To evaluate the clinical features of ischemic colitis, Habu et al 15 looked at 68 patients with ischemic colitis whose age ranged from 22 to 98 years. They found that chronic constipation was commonly associated with ischemic colitis in both young and old patients. Finally, using a research database, investigators found that the relative risk for ischemic colitis was 2.78 times higher for patients with constipation 16. While the exact mechanism has not been determined, it is speculated that increased intraluminal pressure results in decreased blood flow to the mucosa, and predisposes these patients to ischemic attacks.

Cryptitis diagnosis

Your doctor will likely diagnose cryptitis only after ruling out other possible causes for your signs and symptoms. To help confirm a diagnosis of cryptitis, you may have one or more of the following tests and procedures:

Blood tests

- Tests for anemia or infection. Your doctor may suggest blood tests to check for anemia — a condition in which there aren’t enough red blood cells to carry adequate oxygen to your tissues — or to check for signs of infection from bacteria or viruses.

- Fecal occult blood test. You may need to provide a stool sample so that your doctor can test for hidden blood in your stool.

Endoscopic procedures

- Colonoscopy. This exam allows your doctor to view your entire colon using a thin, flexible, lighted tube with an attached camera. During the procedure, your doctor can also take small samples of tissue (biopsy) for laboratory analysis. Sometimes a tissue sample can help confirm a diagnosis.

- Flexible sigmoidoscopy. Your doctor uses a slender, flexible, lighted tube to examine the rectum and sigmoid, the last portion of your colon. If your colon is severely inflamed, your doctor may perform this test instead of a full colonoscopy.

Imaging procedures

- X-ray. If you have severe symptoms, your doctor may use a standard X-ray of your abdominal area to rule out serious complications, such as a perforated colon.

- Computerized tomography (CT) scan. You may have a CT scan — a special X-ray technique that provides more detail than a standard X-ray does. This test looks at the entire bowel as well as at tissues outside the bowel. CT enterography is a special CT scan that provides better images of the small bowel. This test has replaced barium X-rays in many medical centers.

- Magnetic resonance imaging (MRI). An MRI scanner uses a magnetic field and radio waves to create detailed images of organs and tissues. An MRI is particularly useful for evaluating a fistula around the anal area (pelvic MRI) or the small intestine (MR enterography). Unlike a CT, there is no radiation exposure with an MRI.

Cryptitis treatment

Cryptitis treatment involves treating the underlying cause.

The treatment of diverticulitis depends on how serious the symptoms are. Some people may need to be in the hospital, but most of the time, the problem can be treated at home. No specific foods are known to trigger diverticulitis attacks. And no special diet has been proved to prevent attacks. In the past, people with small pouches (diverticula) in the lining of the colon were told to avoid nuts, seeds and popcorn. It was thought that these foods could lodge in diverticula and cause inflammation (diverticulitis). But there’s no evidence that these foods cause diverticulitis.

Once these pouches have formed, you will have them for life. Diverticulitis can return, but some doctors think a high-fiber diet may lessen your chances of a recurrence.

If you have diverticula, focus on eating a healthy diet that’s high in fiber. High-fiber foods, such as fruits, vegetables and whole grains, soften waste and help it pass more quickly through your colon. This reduces pressure within your digestive tract, which may help reduce the risk of diverticula forming and becoming inflamed.

If you think that you’re having a diverticulitis attack, talk to your doctor. Your doctor may suggest that you follow a clear liquid diet for a few days to let your digestive tract rest and heal. Your doctor may also treat you with antibiotics. After you are better, your doctor will suggest that you add more fiber to your diet. Eating more fiber can help prevent future attacks. If you have bloating or gas, reduce the amount of fiber you eat for a few days.

Inflammatory bowel disease

For inflammatory bowel disease, the goal of treatment is to reduce the inflammation that triggers your signs and symptoms. In the best cases, this may lead not only to symptom relief but also to long-term remission and reduced risks of complications. Inflammatory bowel disease treatment usually involves either drug therapy or surgery.

Anti-inflammatory drugs

Anti-inflammatory drugs are often the first step in the treatment of inflammatory bowel disease. Anti-inflammatories include corticosteroids and aminosalicylates, such as mesalamine (Asacol HD, Delzicol, others), balsalazide (Colazal) and olsalazine (Dipentum). Which medication you take depends on the area of your colon that’s affected.

Immune system suppressors

These drugs work in a variety of ways to suppress the immune response that releases inflammation-inducing chemicals in the intestinal lining. For some people, a combination of these drugs works better than one drug alone.

Some examples of immunosuppressant drugs include azathioprine (Azasan, Imuran), mercaptopurine (Purinethol, Purixan), cyclosporine (Gengraf, Neoral, Sandimmune) and methotrexate (Trexall).

One class of drugs called tumor necrosis factor (TNF)-alpha inhibitors, or biologics, works by neutralizing a protein produced by your immune system. Examples include infliximab (Remicade), adalimumab (Humira) and golimumab (Simponi). Other biologic therapies that may be used are natalizumab (Tysabri), vedolizumab (Entyvio) and ustekinumab (Stelara).

Antibiotics

Antibiotics may be used in addition to other medications or when infection is a concern — in cases of perianal Crohn’s disease, for example. Frequently prescribed antibiotics include ciprofloxacin (Cipro) and metronidazole (Flagyl).

Other medications and supplements

In addition to controlling inflammation, some medications may help relieve your signs and symptoms, but always talk to your doctor before taking any over-the-counter medications. Depending on the severity of your inflammatory bowel disease, your doctor may recommend one or more of the following:

- Anti-diarrheal medications. A fiber supplement — such as psyllium powder (Metamucil) or methylcellulose (Citrucel) — can help relieve mild to moderate diarrhea by adding bulk to your stool. For more severe diarrhea, loperamide (Imodium A-D) may be effective.

- Pain relievers. For mild pain, your doctor may recommend acetaminophen (Tylenol, others). However, ibuprofen (Advil, Motrin IB, others), naproxen sodium (Aleve) and diclofenac sodium (Voltaren) likely will make your symptoms worse and can make your disease worse as well.

- Iron supplements. If you have chronic intestinal bleeding, you may develop iron deficiency anemia and need to take iron supplements.

- Calcium and vitamin D supplements. Crohn’s disease and steroids used to treat it can increase your risk of osteoporosis, so you may need to take a calcium supplement with added vitamin D.

Nutritional support

Your doctor may recommend a special diet given via a feeding tube (enteral nutrition) or nutrients injected into a vein (parenteral nutrition) to treat your inflammatory bowel disease. This can improve your overall nutrition and allow the bowel to rest. Bowel rest can reduce inflammation in the short term.

If you have a stenosis or stricture in the bowel, your doctor may recommend a low-residue diet. This will help to minimize the chance that undigested food will get stuck in the narrowed part of the bowel and lead to a blockage.

Surgery

If diet and lifestyle changes, drug therapy, or other treatments don’t relieve your inflammatory bowel disease signs and symptoms, your doctor may recommend surgery.

- Surgery for ulcerative colitis. Surgery can often eliminate ulcerative colitis. But that usually means removing your entire colon and rectum (proctocolectomy). In most cases, this involves a procedure called an ileal pouch anal anastomosis. This procedure eliminates the need to wear a bag to collect stool. Your surgeon constructs a pouch from the end of your small intestine. The pouch is then attached directly to your anus, allowing you to expel waste relatively normally. In some cases a pouch is not possible. Instead, surgeons create a permanent opening in your abdomen (ileal stoma) through which stool is passed for collection in an attached bag.

- Surgery for Crohn’s disease. Up to one-half of people with Crohn’s disease will require at least one surgery. However, surgery does not cure Crohn’s disease. During surgery, your surgeon removes a damaged portion of your digestive tract and then reconnects the healthy sections. Surgery may also be used to close fistulas and drain abscesses. The benefits of surgery for Crohn’s disease are usually temporary. The disease often recurs, frequently near the reconnected tissue. The best approach is to follow surgery with medication to minimize the risk of recurrence.

Infectious colitis

Not all infectious colitis requires antibiotic therapy; patients with mild to moderate Campylobacter jejuni or Salmonella infections do not need antibiotic therapy because the infection is self-limited. Treatment with quinolinic acid antibiotics is only for patients with dysentery and high fever suggestive of bacteremia. Also, patients with AIDS, malignancy, transplantation, prosthetic implants, valvular heart disease, or extreme age will require antibiotic therapy. For mild to moderate C. difficile infection, metronidazole is the preferred treatment. In severe cases of Clostridium difficile infection, oral vancomycin is the recommended approach. In complicated cases, oral vancomycin with intravenous metronidazole is the recommendation 17.

In patients, particularly children, with enterohemorrhagic Escherichia coli (E. coli O157: 7H and non-O157: H7), antibiotics are not recommended for treatment of infection because killing the bacteria can lead to increased release of Shigella toxins and enhance the risk of the hemolytic uremic syndrome 18.

Because of rising multidrug resistance to antituberculous treatment, cases with active Mycobacterium tuberculosis colitis receive therapy with rifampin, isoniazid, pyrazinamide, and ethambutol for 9 to 12 months. The reader is advised to review the recent guidelines by the World Health Organisation on the treatment of developing resistance in tuberculosis 19.

The majority of patients with cytomegalovirus colitis who are immunocompetent may need no treatment with antiviral medications. However, antiviral therapy in immunocompetent patients with cytomegalovirus colitis could be limited to males over the age of 55 who suffer from severe disease and have co-morbidities affecting the immune system such as diabetes mellitus or chronic renal failure; consider an assessment of the colon viral load. The drug of choice is oral or intravenous ganciclovir 19.

Treatment of Entamoeba histolytica is recommended even in asymptomatic individuals. Noninvasive colitis may be treated with paromomycin, to eliminate intraluminal cysts. Metronidazole is the antimicrobial of choice for invasive amoebiasis. Medications with longer half-lives (such as tinidazole, and ornidazole), allow for shorter treatment periods and are better tolerated. After completing a 10-day course of a nitroimidazole, the patient should be placed on paromomycin to eradicate the luminal parasites. Fulminant amoebic colitis requires the addition of broad-spectrum antibiotics to the treatment due to the risk of bacterial translocation 20.

Because of emerging resistance in gonorrhea, current treatment as per current guidelines comprises intramuscular ceftriaxone 500 mg together with an oral dose of azithromycin 1 g. Alternative protocols could be cefixime 400 mg stat or ciprofloxacin 500 mg orally stat.

The treatment of lymphogranuloma venereum comprises doxycycline orally twice daily for 3 weeks or erythromycin 500 mg orally four times daily for 3 weeks 21.

Genital/rectal herpes simplex is treated with acyclovir 400 mg three times daily or valaciclovir 500 mg twice daily for 5 days. Analgesia and saline bathing could sooth the pain. Intravenous therapy is an option if the patient tolerates oral therapy poorly. Consider prolonging treatment if new lesions develop. For recurrent genital/rectal herpes, lesions are usually mild, may need no specific treatment. Symptomatic treatment could help. Challenging cases such as those with recurrence at short intervals may require referral for specialized advice. The partner should also have an examination and treatment if the lesion is active.

Syphilis treatment is with penicillin (the drug of choice). A single dose of 2.4 megaunits of intramuscular benzathine benzylpenicillin is the recommendation for early syphilis or 3 doses at weekly intervals with late syphilis. Doxycycline could be an alternative treatment for individuals sensitive to penicillin. Follow up patients to ensure clearance from infection and notification are required 22.

Radiation enteritis

Medical management includes treating diarrhea, dehydration, malabsorption, and abdominal or rectal discomfort. Symptoms usually resolve with medications, dietary changes, and rest. If symptoms become severe despite these measures, a treatment break may be warranted.

Medications may include the following:

- Kaopectate, an antidiarrheal agent. Dose: 30 cc to 60 cc by mouth after each loose bowel movement.

- Lomotil (diphenoxylate hydrochloride with atropine sulfate). Usual dose: One or two tablets by mouth every 4 hours as needed. Dose can be adjusted to individual patients and patterns of diarrhea. For example, one patient may achieve control of diarrhea with one tablet 3 times a day, while another patient may require two tablets every 4 hours. Patients are not to take more than eight tablets of Lomotil within a 24-hour period.

- Paregoric, an antidiarrheal agent. Usual dose: 1 teaspoon by mouth 4 times a day as needed for diarrhea. Paregoric may also be alternated with Lomotil.

- Cholestyramine, a bile salt sequestering agent. Dose: one package by mouth after each meal and at bedtime.

- Donnatal, an anticholinergic antispasmodic agent to alleviate bowel cramping. Dose: One or two tablets every 4 hours as needed.

- Imodium (loperamide hydrochloride), a synthetic antidiarrheal agent. Recommended initial dose: two capsules (4 mg) by mouth every 4 hours, followed by one capsule (2 mg) by mouth after each unformed stool. Daily total dose should not exceed 16 mg (eight capsules).

In addition to these medications, opioids may offer relief from abdominal pain. If proctitis is present, a steroid foam given rectally may offer relief from symptoms. Finally, if patients with pancreatic cancer are experiencing diarrhea during radiation therapy, they will be evaluated for oral pancreatic enzyme replacement, as deficiencies in these enzymes alone can cause diarrhea.

Nutrition

Damage to the intestinal villi from radiation therapy results in a reduction or loss of enzymes, one of the most important of these being lactase. Lactase is essential in the digestion of milk and milk products. Although there is no evidence that a lactose-restricted diet will prevent radiation enteritis, a diet that is lactose free, low fat, and low residue can be an effective modality in symptom management 23.

Foods to avoid

- Milk and milk products. Exceptions are buttermilk and yogurt, which are often tolerated because lactose is altered by the presence of Lactobacillus. Processed cheese may also be tolerated because the lactose is removed with the whey when it is separated from the cheese curd. Milkshake supplements such as Ensure are lactose free and may be used.

- Whole-bran bread and cereal.

- Nuts, seeds, and coconuts.

- Fried, greasy, or fatty foods.

- Fresh and dried fruit and some fruit juices such as prune juice.

- Raw vegetables.

- Rich pastries.

- Popcorn, potato chips, and pretzels.

- Strong spices and herbs.

- Chocolate, coffee, tea, and soft drinks with caffeine.

- Alcohol and tobacco.

Foods to encourage

- Fish, poultry, and meat that is cooked, broiled, or roasted.

- Bananas, applesauce, peeled apples, and apple and grape juices.

- White bread and toast.

- Macaroni and noodles.

- Baked, boiled, or mashed potatoes.

- Cooked vegetables that are mild, such as asparagus tips, green and waxed beans, carrots, spinach, and squash.

- Mild processed cheese, eggs, smooth peanut butter, buttermilk, and yogurt.

Helpful hints

- Ingest food at room temperature 24.

- Drink 3,000 ml of fluid per day. Allow carbonated beverages to lose carbonation before being ingested.

- Add nutmeg to food, which will help decrease mobility of gastrointestinal tract.

- Start a low-residue diet on day 1 of radiation therapy treatment.

Ischemic colitis

Once the diagnosis of ischemic colitis has been made, patients should be aggressively resuscitated and receive broad-spectrum intravenous antibiotics 25. If the patients are hemodynamically stable and do not have signs of peritonitis, they should undergo urgent colonoscopy. The treatment is dictated by the findings of physical examination and the appearance of the colonic mucosa on endoscopy. Patients with peritoneal signs or nonviable bowel on endoscopy need immediate operative intervention; otherwise they can be managed medically.

Medical management consists of bowel rest, intravenous fluids, and broad-spectrum antibiotics. Nasogastric tubes should be used selectively in patients with distention or ileus. A “splanchnic focused” resuscitation with avoidance of vasoconstrictive medications should be implemented. Mental status, abdominal pain, and urine output should be monitored to assess for signs of adequate end organ perfusion. Additional endpoints of resuscitation, including lactate levels and mixed venous oxygen saturation, may be indicated, depending upon the severity of the attack.

Surgical treatment

In the acute setting, the operative procedure is dictated by the extent of injury to the bowel and the overall condition of the patient. All nonviable bowels must be resected. A damage-control approach may be indicated if intraoperative monitoring reveals hypothermia, coagulopathy, and acidosis. Second look operations may be useful if there are areas of questionable perfusion. The decision to perform an anastomosis should be based on the immediate condition of the patients as well as an assessment of their comorbidities and nutritional status.

After resolution of the acute attack, a small number of patients will develop strictures in the colon. Colonoscopy with biopsy is recommended to evaluate for malignancy or other pathology. Depending upon the severity of the symptoms and the degree of stenosis, dilation or surgical resection may be indicated.

Ischemic colitis outcomes

Acute ischemic colitis usually resolves with medical care but morbidity and mortality rates remain high for patients requiring surgery. A recent meta-analysis revealed that 80.3% of the patients were managed medically with a mortality rate of 6.2%. Surgery was associated with a 39.3% mortality rate 26. This is consistent with a retrospective review of 49 patients with ischemic colitis looking at the outcome of surgical intervention. Emergency colectomy was performed in 81.6%. The authors reported a morbidity rate of 85.7% and a mortality rate of 44.9%. Preoperative hypotension was a significant risk factor for mortality 27.

The long-term prognosis for these patients is more favorable. A retrospective review of 135 patients with ischemic colitis reported that recurrence rates were 2.9 and 9.7% at 1 and 5 years, respectively. Five-year survival was 69%, but most patients died because of other causes 28.

References- Cryptitis. The American Journal of Surgery Volume 36, Issue 1, April 1937, Pages 249-251

- Al-Hussaini, AA.; Machida, HM.; Butzner, JD. (2003). “Crohn’s disease and cheilitis”. Canadian Journal of Gastroenterology Volume 17, Issue 7, Pages 445-447 http://downloads.hindawi.com/journals/cjgh/2003/368754.pdf

- West, AB.; Losada, M. “The pathology of diverticulosis coli”. J Clin Gastroenterol. 38 (5 Suppl 1): S11–6. https://www.ncbi.nlm.nih.gov/pubmed/15115923

- Hovdenak, N.; Fajardo, LF.; Hauer-Jensen, M. (2000). “Acute radiation proctitis: a sequential clinicopathologic study during pelvic radiotherapy”. Int J Radiat Oncol Biol Phys. 2000 Nov 1;48(4):1111-7. https://doi.org/10.1016/S0360-3016(00)00744-6

- O’Brien PH, Jenrette JM, Garvin AJ: Radiation enteritis. Am Surg 53 (9): 501-4, 1987.

- Yeoh EK, Horowitz M: Radiation enteritis. Surg Gynecol Obstet 165 (4): 373-9, 1987.

- Gallagher MJ, Brereton HD, Rostock RA, et al.: A prospective study of treatment techniques to minimize the volume of pelvic small bowel with reduction of acute and late effects associated with pelvic irradiation. Int J Radiat Oncol Biol Phys 12 (9): 1565-73, 1986.

- Schuler JG, Hudlin MM. Cecal necrosis: infrequent variant of ischemic colitis. Report of five cases. Dis Colon Rectum. 2000 May. 43(5):708-12.

- Nielsen OH, Vainer B, Rask-Madsen J. Non-IBD and noninfectious colitis. Nat Clin Pract Gastroenterol Hepatol. 2008 Jan. 5(1):28-39.

- Ischemic Colitis Imaging. https://emedicine.medscape.com/article/366808-overview

- Steele SR. Ischemic colitis complicating major vascular surgery. Surg Clin North Am. 2007 Oct. 87(5):1099-114, ix

- Mancuso MA, Cheung YY, Silas AM, Chertoff JD, Dickey KW. Case 120: ischemic colitis limited to the cecum. Radiology. 2007 Sep. 244(3):919-22.

- Leth T, Wilkens R, Bonderup OK. Sonographic and Endoscopic Findings in Cocaine-Induced Ischemic Colitis. Case Rep Gastrointest Med. 2015. 2015:680937.

- Matsumoto T, Iida M, Kimura Y, Nanbu T, Fujishima M. Clinical features in young adult patients with ischaemic colitis. J Gastroenterol Hepatol. 1994;9(6):572–575.

- Habu Y, Tahashi Y, Kiyota K. et al.Reevaluation of clinical features of ischemic colitis. Analysis of 68 consecutive cases diagnosed by early colonoscopy. Scand J Gastroenterol. 1996;31(9):881–886.

- Suh D C, Kahler K H, Choi I S, Shin H, Kralstein J, Shetzline M. Patients with irritable bowel syndrome or constipation have an increased risk for ischaemic colitis. Aliment Pharmacol Ther. 2007;25(6):681–692.

- Di X, Bai N, Zhang X, Liu B, Ni W, Wang J, Wang K, Liang B, Liu Y, Wang R. A meta-analysis of metronidazole and vancomycin for the treatment of Clostridium difficile infection, stratified by disease severity. Braz J Infect Dis. 2015 Jul-Aug;19(4):339-49.

- Tarr PI, Gordon CA, Chandler WL. Shiga-toxin-producing Escherichia coli and haemolytic uraemic syndrome. Lancet. 2005 Mar 19-25;365(9464):1073-86.

- Falzon D, Schünemann HJ, Harausz E, et al. World Health Organization treatment guidelines for drug-resistant tuberculosis, 2016 update. Eur Respir J. 2017;49(3):1602308. Published 2017 Mar 22. doi:10.1183/13993003.02308-2016 https://www.ncbi.nlm.nih.gov/pmc/articles/PMC5399349

- Haque R, Huston CD, Hughes M, Houpt E, Petri WA. Amebiasis. N. Engl. J. Med. 2003 Apr 17;348(16):1565-73.

- Stoner BP, Cohen SE. Lymphogranuloma Venereum 2015: Clinical Presentation, Diagnosis, and Treatment. Clin. Infect. Dis. 2015 Dec 15;61 Suppl 8:S865-73.

- Dean R, Gill D, Buchan D. Salmonella colitis as an unusual cause of elevated serum lipase. Am J Emerg Med. 2017 May;35(5):800.e5-800.e6.

- Stryker JA, Bartholomew M: Failure of lactose-restricted diets to prevent radiation-induced diarrhea in patients undergoing whole pelvis irradiation. Int J Radiat Oncol Biol Phys 12 (5): 789-92, 1986.

- Yasko JM: Care of the Client Receiving External Radiation Therapy. Reston, Va: Reston Publishing Company, Inc., 1982.

- FitzGerald JF, Hernandez Iii LO. Ischemic colitis. Clin Colon Rectal Surg. 2015;28(2):93–98. doi:10.1055/s-0035-1549099 https://www.ncbi.nlm.nih.gov/pmc/articles/PMC4442720

- O’Neill S, Yalamarthi S. Systematic review of the management of ischaemic colitis. Colorectal Dis. 2012;14(11):e751–e763

- Ryoo S B, Oh H K, Ha H K, Moon S H, Choe E K, Park K J. The outcomes and prognostic factors of surgical treatment for ischemic colitis: what can we do for a better outcome? Hepatogastroenterology. 2014;61(130):336–342.

- Cosme A, Montoro M, Santolaria S. et al.Prognosis and follow-up of 135 patients with ischemic colitis over a five-year period. World J Gastroenterol. 2013;19(44):8042–8046.