Dientamoeba fragilis

Dientamoeba fragilis is a single-celled protozoan parasite that lives in the large intestine of people 1. This protozoan parasite produces trophozoites; cysts have not been identified. Dientamoeba fragilis infection is common worldwide, including in the United States. Estimated Dientamoeba fragilis prevalence in the general population in the United States and in other developed countries is most commonly 2-5%. However, much higher prevalence rates (19-69%) have been reported in specific populations, such as individuals living in crowded conditions (eg, institutions, communal living), individuals living in conditions with poor hygiene, and those traveling to developing countries 2. A prospective study from Spain that included 44 Dientamoeba fragilis patients and their 97 household contacts reported that 50.5% of household contacts had a positive PCR for Dientamoeba fragilis. The study also reported that patients with children were more associated with coinfection 3.

Dientamoeba fragilis intestinal infection may be either asymptomatic or symptomatic. Despite its name, Dientamoeba fragilis is not an ameba but an intestinal flagellate that lacks external flagella, most closely related to trichomonads. In human stool specimens, Dientamoeba fragilis is almost always found solely as a trophozoite. However, the rare presence of putative cyst and precyst forms in clinical specimens has been reported; their transmission potential is being investigated. Other aspects of the transmission and pathogenicity of Dientamoeba fragilis also are poorly understood. Dientamoeba fragilis is found worldwide. Infection appears to be more common in children.

Dientamoeba fragilis colonization may occur without development of disease, and, in adults, asymptomatic colonization was once thought to be present in 75-85% of individuals infected by the parasite. More recently, it is not believed that asymptomatic carriage is as prevalent as once thought and in children symptomatic disease develops in as many as 90% of those colonized. In 2014, new research was presented at the 24th European Congress of Clinical Microbiology and Infectious Diseases that questioned the pathogenicity of the Dientamoeba fragilis parasite 4.

Dientamoeba fragilis is primarily a parasite of humans. Trophozoites have been identified in some other mammals (e.g., non-human primates, swine), but the epidemiologic significance of these hosts is unknown.

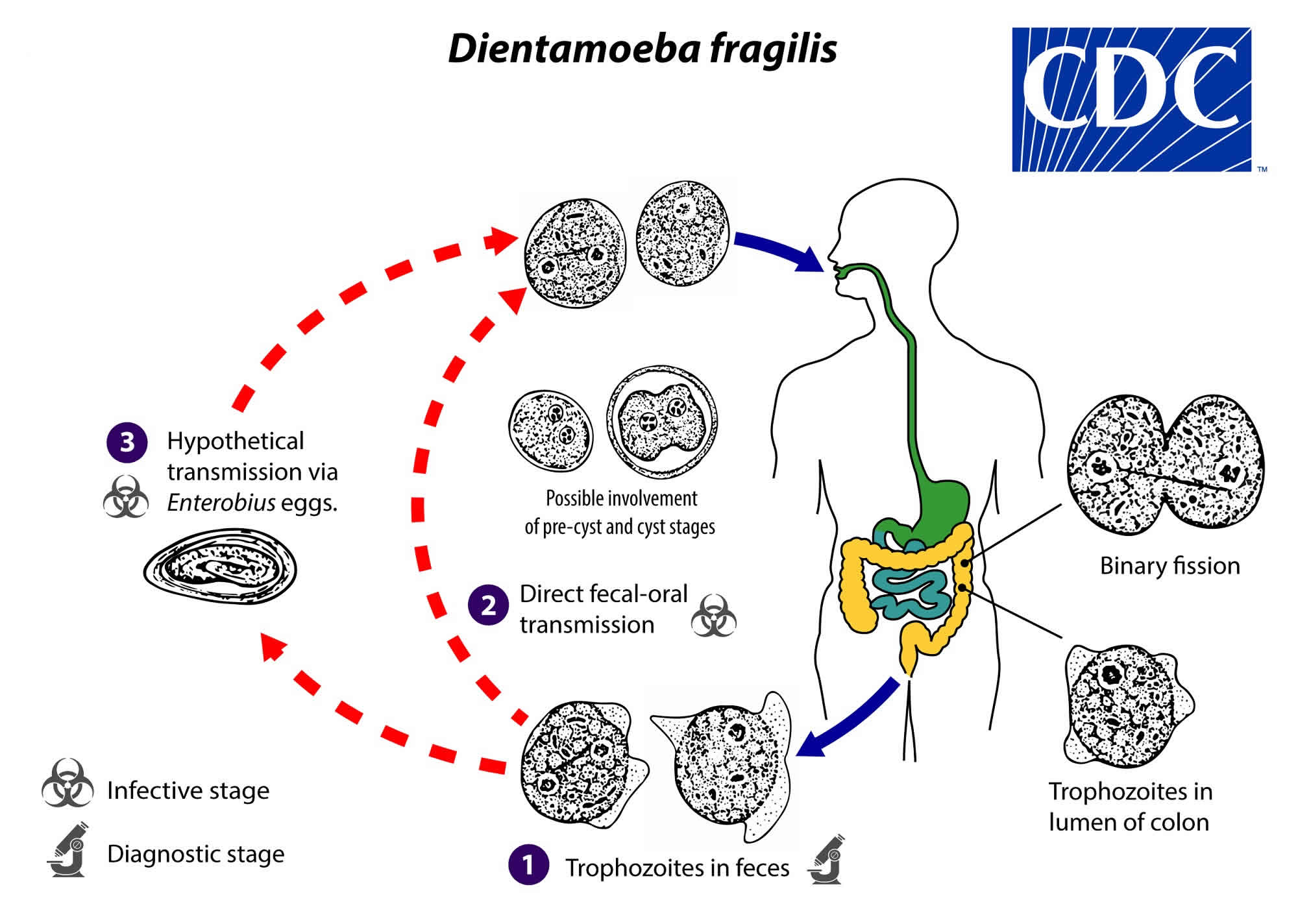

Dientamoeba fragilis life cycle

The complete life cycle of Dientamoeba fragilis has not yet been elucidated; assumptions have been made on the basis of clinical observations and the biology of related species (in particular, Histomonas meleagridis, a parasite of galliform birds). Trophozoites are found in the lumen of the large intestine, where they multiply via binary fission, and are shed in the stool (number #1). Historically, only the trophozoite stage of Dientamoeba fragilis had been detected. However, rare putative cyst and precyst forms have been described in human clinical specimens; whether and in what settings transmission to humans occurs via ingestion of such forms in contrast or in addition to other fecal-oral transmission routes is not yet known (number #2). Transmission via helminth eggs (e.g., via Enterobius vermicularis eggs) has been postulated (number #3).

Dientamoeba fragilis trophozoites measure 5 to 15 µm; cyst-like stages are rare. Pseudopodia are angular to broad-lobed and transparent. Although most trophozoites are binucleate, some have only one nucleus. The nucleus typically has a fragmented karyosome with discrete chromatin granules, and a thin nuclear membrane may be visible.

Figure 1. Dientamoeba fragilis life cycle

How do people get infected with Dientamoeba fragilis?

This question is difficult to answer because scientists aren’t sure how Dientamoeba fragilis is spread. Most likely, people get infected by accidentally swallowing the parasite; this is called fecal-oral transmission. The parasite is fragile; it probably cannot live very long in the environment (after it is passed in feces) or in stomach acid (after it is swallowed). An unproven possibility is that pinworm eggs (or the eggs of another parasite) help protect and spread Dientamoeba fragilis.

Who is at greatest risk for Dientamoeba fragilis infection?

Anyone can become infected with Dientamoeba fragilis. However, the risk for Dientamoeba fragilis infection might be higher for people who live in or travel to settings with poor sanitary conditions.

Dientamoeba fragilis infection causes

The mode of transmission is believed to be through direct fecal-oral spread and, possibly, through the eggs of Enterobius Vermicularis (pinworm). Pigs have recently been identified as a natural host for Dientamoeba fragilis 5, raising the possibility of transmission from porcine waste and the parasite has also been identified in untreated wastewater 6.

Dientamoeba fragilis infection prevention

- Wash your hands with soap and warm water after using the toilet, after changing diapers, and before preparing or eating food.

- Teach children the importance of washing hands to prevent infection.

Dientamoeba fragilis symptoms

Dientamoeba fragilis are associated with symptomatic infection in humans. Both asymptomatic and symptomatic infection (e.g., with various nonspecific gastrointestinal symptoms) have been reported. Many infected people do not have any symptoms. The most common symptoms are diarrhea and abdominal pain 7. Symptoms also can include loss of appetite, weight loss, nausea, and fatigue. The reported clinical manifestations have sometimes been described as similar to those of colitis, appendicitis, or irritable bowel syndrome. Dientamoeba fragilis infection does not spread from the intestine to other parts of the body.

In acute Dientamoeba fragilis infection, diarrhea is the predominant symptom, which lasts 1-2 weeks 8. Diarrheal history may vary, with either consistently frequent stools (1-4 stools per day) or episodic occurrence of diarrhea. Stools are greenish brown, and their consistency varies from watery to sticky. Occasionally, mucus is noted in the stools, but hematochezia is unusual. Chronic infection is diagnosed when duration of symptoms is greater than 1-2 months. The most common symptom in chronic infection is abdominal pain.

Other gastrointestinal complaints include the following 9:

- Anorexia

- Weight loss

- Nausea

- Vomiting

- Bloating

- Flatulence

- Alternating constipation and diarrhea

Nonintestinal complaints include the following:

- Headache

- Fever

- Malaise

- Fatigue

- Irritability

- Weakness

- Pruritus

- Urticaria

Dientamoeba fragilis diagnosis

Your health care provider will ask you to provide stool specimens for testing. Because the parasite is not always found in every specimen, you might be asked to submit stool from more than one day. You might also be tested for pinworm eggs, which sometimes are found in people who are infected with Dientamoeba fragilis.

Dientamoeba fragilis infection typically is diagnosed by detection of Dientamoeba fragilis trophozoites in fecal smears stained with trichrome or another permanent stain. The trophozoite stage of the parasite is not usually detectable if stool concentration methods are used. Dientamoeba fragilis trophozoites can easily be overlooked or misidentified because they are pale-staining and their nuclei sometimes resemble those of Endolimax nana or Entamoeba hartmanni.

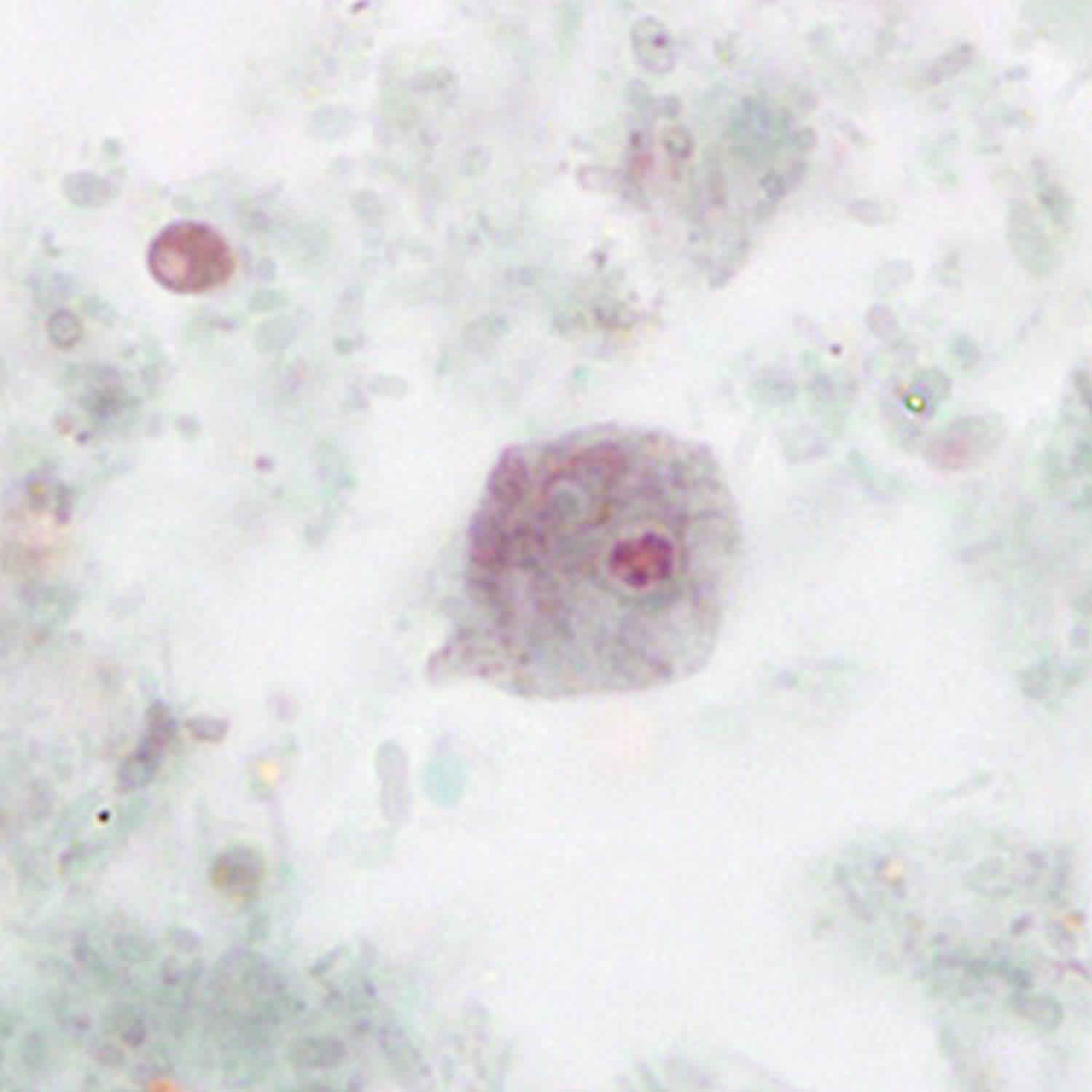

Figure 2. Dientamoeba fragilis trophozoites

Footnote: Although most Dientamoeba fragilis trophozoites are binucleate, some have only one nucleus. Uninucleate form of a trophozoite of Dientamoeba fragilis, stained with trichrome.

[Source 10 ]Dientamoeba fragilis treatment

Safe and effective medications are available to treat Dientamoeba fragilis infection. Examples of several of the most commonly used treatments are provided in the table below. As always, treatment decisions should be individualized.

| Drug* | Dosage regimen for adults |

|---|---|

| Iodoquinol | 650 mg orally three times daily for 20 days |

| OR | |

| Paromomycin | 25–35 mg per kg per day orally, in three divided doses, for 7 days |

| OR | |

| Metronidazole** | 500–750 mg orally three times daily for 10 days |

Footnote:

*Not FDA-approved for this indication.

** Metronidazole is a nitroimidazole drug. The nitroimidazole drugs secnidazole and ornidazole have been used to treat D. fragilis infection but are unavailable in the United States.

Iodoquinol is available for human use in the United States.

Oral paromomycin is available for human use in the United States.

Metronidazole is available for human use in the United States.

[Source 11 ]Iodoquinol

Note on treatment in pregnancy

- Oral iodoquinol has not been assigned a pregnancy category by the Food and Drug Administration. Data on the use of iodoquinol in pregnant women are limited, and risk to the embryo-fetus is unknown. Iodoquinol should be used during pregnancy only if the potential benefit justifies the potential risk to the fetus.

Note on treatment during breastfeeding

- It is not known whether iodoquinol is excreted in breast milk. Iodoquinol should be used with caution in breastfeeding women.

Note on treatment in children

- The safety of iodoquinol in children has not been established.

Paromomycin

Note on treatment in pregnancy

- Oral paromomycin has not been assigned to a pregnancy category by the Food and Drug Administration. Data on the use of oral paromomycin in pregnant women are limited, and the risk to the embryo-fetus probably is low. Oral paromomycin generally is poorly absorbed from the gastrointestinal tract, with minimal, if any, systemic availability.

Note on treatment during breastfeeding

- Oral paromomycin is unlikely to be excreted in breast milk, and the drug generally is poorly absorbed from the gastrointestinal tract.

Note on treatment in children

- The safety of oral paromomycin in children has not been formally evaluated. However, the safety profiles likely are comparable in children and adults.

Metronidazole

Note on treatment in pregnancy

- Pregnancy Category B: Either animal-reproduction studies have not demonstrated a fetal risk but there are no controlled studies in pregnant women or animal-reproduction studies have shown an adverse effect (other than a decrease in fertility) that was not confirmed in controlled studies in women in the first trimester (and there is no evidence of a risk in later trimesters).

- Metronidazole is in pregnancy category B. Data on the use of metronidazole in pregnant women are conflicting. The available evidence suggests use during pregnancy has a low risk of congenital anomalies. Metronidazole may be used during pregnancy in those patients who will clearly benefit from the drug, although its use should be weighed against any potential risks.

Note on treatment during breastfeeding

- Metronidazole is excreted in breast milk. The American Academy of Pediatrics classifies metronidazole as a drug for which the effect on nursing infants is unknown but may be of concern. The World Health Organization (WHO) advises to avoid metronidazole treatment in lactating women. Metronidazole should be used during lactation only if the potential benefit of therapy to the mother justifies the potential risk to the infant.

Note on treatment in children

- The safety of metronidazole in children has not been established. Metronidazole is listed as an antiamebic and antigiardiasis medicine on the WHO Model List of Essential Medicines for Children, intended for the use of children up to 12 years of age.

- Dientamoeba fragilis. https://www.cdc.gov/parasites/dientamoeba/

- Dientamoeba Fragilis Infection. https://emedicine.medscape.com/article/997239-overview

- Menéndez Fernández-Miranda C, Fernández-Suarez J, Rodríguez-Pérez M, Menéndez Fernández-Miranda P, Vázquez F, Boga Ribeiro JA, et al. Prevalence of D. fragilis infection in the household contacts of a group of infected patients. Enferm Infecc Microbiol Clin. 2017 Oct 24.

- New Research Questions Pathogenicity of Parasite D fragilis. https://www.medscape.com/viewarticle/825137

- Cacciò SM, Sannella AR, Manuali E, Tosini F, Sensi M, Crotti D, et al. Pigs as natural hosts of Dientamoeba fragilis genotypes found in humans. Emerg Infect Dis. 2012 May. 18(5):838-41.

- Stark D, Roberts T, Marriott D, Harkness J, Ellis JT. Detection and transmission of Dientamoeba fragilis from environmental and household samples. Am J Trop Med Hyg. 2012 Feb. 86(2):233-6.

- Stark D, Barratt J, Roberts T, Marriott D, Harkness J, Ellis J. A review of the clinical presentation of dientamoebiasis. Am J Trop Med Hyg. 2010 Apr. 82(4):614-9.

- Cuffari C, Oligny L, Seidman EG. Dientamoeba fragilis masquerading as allergic colitis. J Pediatr Gastroenterol Nutr. 1998 Jan. 26(1):16-20.

- Johnson EH, Windsor JJ, Clark CG. Emerging from obscurity: biological, clinical, and diagnostic aspects of Dientamoeba fragilis. Clin Microbiol Rev. 2004 Jul. 17(3):553-70, table of contents.

- Dientamoeba fragilis Infection. https://www.cdc.gov/dpdx/dientamoeba/index.html

- Resources for Health Professionals. https://www.cdc.gov/parasites/dientamoeba/health_professionals/index.html