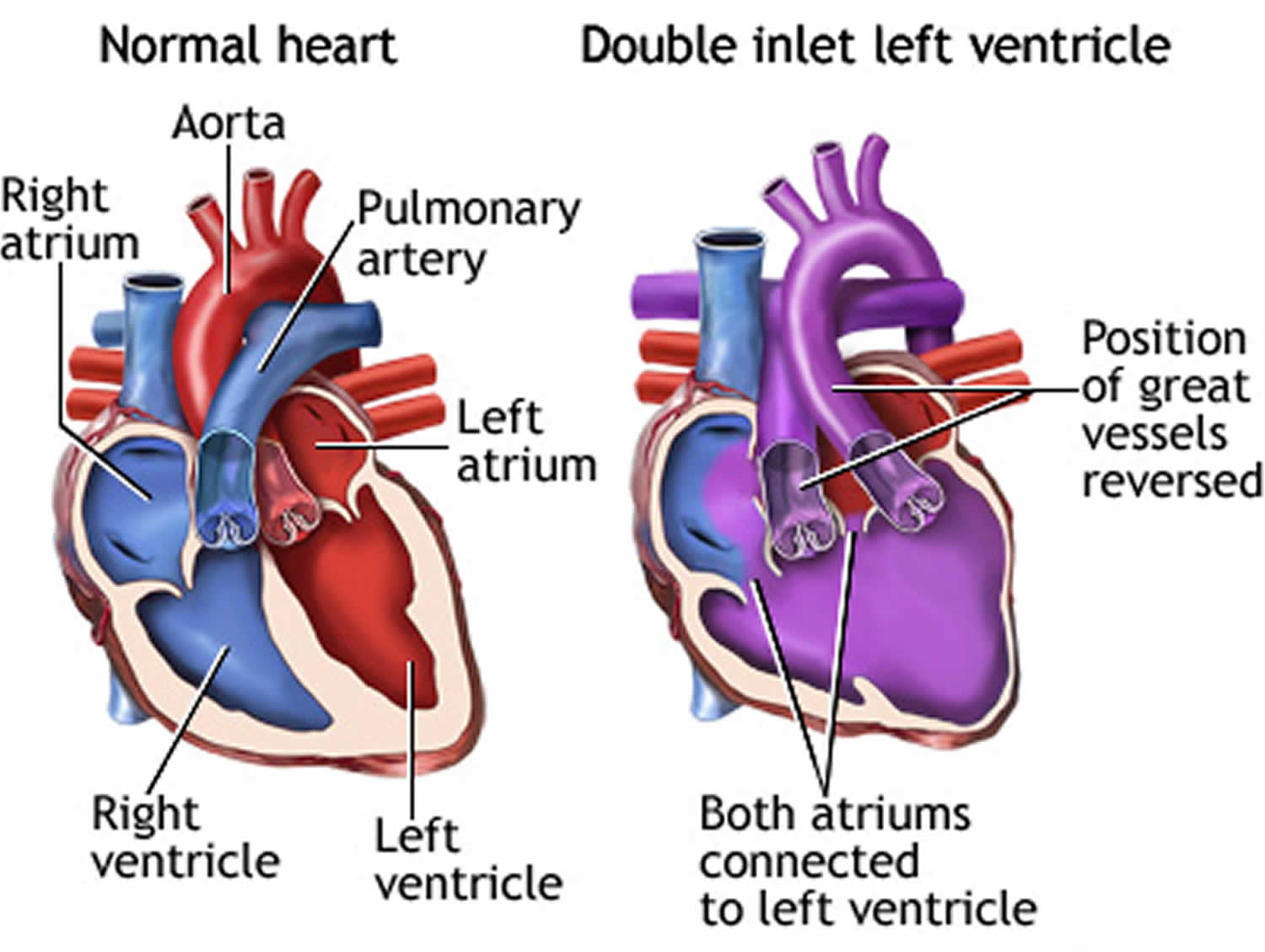

Double inlet left ventricle

Double inlet left ventricle or DILV, is a congenital (present from birth) heart abnormality where both the left and right atria (plural for atrium) are connected to the left ventricle. Babies born with double inlet left ventricle have only one working pumping chamber (ventricle) in their heart. Double inlet left ventricle (DILV) is one of several heart defects known as single or common ventricle defects. People with DILV have a large left ventricle (LV) and a small (hypoplastic) right ventricle (RV). The arteries usually arise with the aorta from the right ventricle (RV) and the pulmonary artery from the left ventricle (LV) (transposition of the great arteries). Normally, the aorta leaves the left ventricle carrying oxygen-rich (red) blood to the body, and the pulmonary artery leaves the right ventricle carrying oxygen-poor (blue) blood to the lungs to get oxygen. The reversal in transposition of the great arteries changes the way blood circulates through the body, causing a shortage of oxygen in the blood leaving the heart going to the rest of the body.

People with DILV often also have other heart problems, such as:

- Coarctation of the aorta (narrowing of the aorta)

- Pulmonary atresia (pulmonary valve of the heart is not formed properly)

- Pulmonary valve stenosis (narrowing of the pulmonary valve)

In the normal heart, the right and left ventricles receive blood from the right and left atria. The atria are the upper chambers of the heart. Oxygen-poor blood returning from the body flows to the right atrium and right ventricle. The right ventricle is the pumping chamber that sends oxygen-poor blood to the lungs. The right ventricle pumps blood to the pulmonary artery. This is the blood vessel that carries blood to the lungs to pick up oxygen.

Blood with fresh oxygen returns to the left atrium and left ventricle. The left ventricle is the pumping chamber of the heart that sends oxygen-rich blood to the body. The aorta then carries oxygen-rich blood to the rest of the body from the left ventricle. The aorta is the major artery leading out of the heart.

In people with DILV, only the left ventricle is developed. Both atria empty blood into this ventricle. This means that oxygen-rich blood mixes with oxygen-poor blood. The mixture is then pumped to both the body and the lungs.

DILV can happen if the large blood vessels arising from the heart are in the wrong positions. The aorta arises from the small right ventricle and the pulmonary artery arises from the left ventricle. It can also occur when the arteries are in normal positions and arise from the usual ventricles. In this case, blood flows from the left to right ventricle through a hole between the chambers called a ventricular septal defect (VSD).

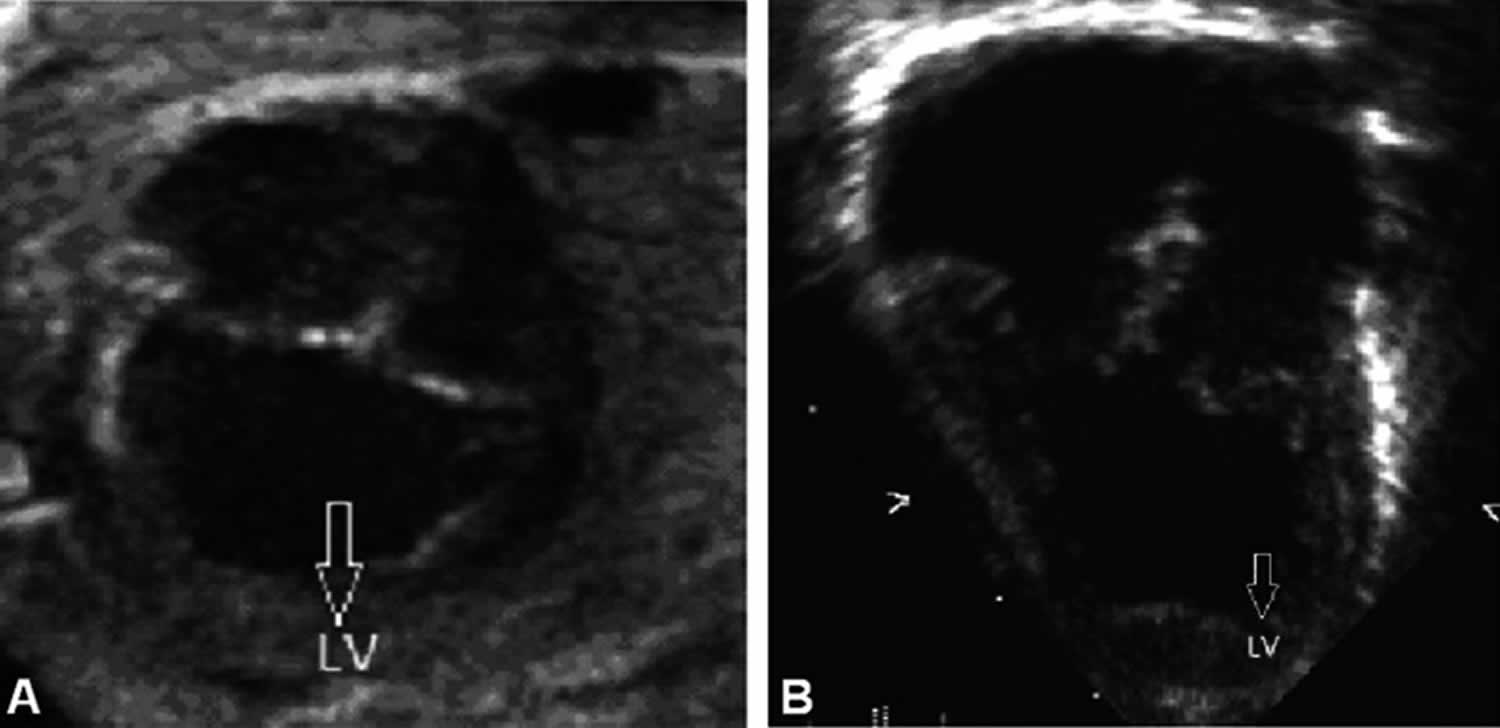

Figure 1. Double inlet left ventricle echo

Footnote: (A) Two-dimensional fetal echocardiogram at 24 weeks of gestation. (B) Two-dimensional transthoracic echocardiogram at birth. Both images demonstrate double-inlet left ventricle (two atrioventricular valves empty in a smooth walled left ventricle).

[Source 1 ]Double inlet left ventricle causes

The cause of double inlet left ventricle is unknown, but the defect is likely to occur early in a pregnancy when the baby’s heart is developing.

Double inlet left ventricle symptoms

Symptoms of double inlet left ventricle usually appear in the early weeks of a baby’s life and include:

- Bluish color to the skin and lips (cyanosis) due to low oxygen in the blood

- Failure to gain weight and grow (failure to thrive)

- Pale skin (pallor)

- Poor feeding from becoming tired easily

- Sweating

- Swollen legs or abdomen

- Trouble breathing

- Fast heartbeat

- Heart murmur (an unusual heart sound)

- Fluid buildup around the lungs

- Heart failure.

Signs of double inlet left ventricle may include:

- Abnormal heart rhythm, as seen on an electrocardiogram

- Buildup of fluid around the lungs

- Heart failure

- Heart murmur

- Rapid heartbeat

Many babies with double inlet left ventricle have other abnormalities in the heart or the main arteries. These abnormalities can block the flow of blood to the lungs.

Double inlet left ventricle complications

Complications of double inlet left ventricle include:

- Clubbing (thickening of the nail beds) on the toes and fingers (late sign)

- Heart failure

- Frequent pneumonia

- Heart rhythm problems

- Death

Double inlet left ventricle diagnosis

Your baby’s doctor will perform a physical examination and listen to your baby’s heartbeat with a stethoscope in order to hear if there is a heart murmur. The doctor may also order various tests, including:

- Chest x-ray

- An electrocardiogram (ECG) to measure the baby heart’s electrical activity

- Cardiac catheterization (a thin tube is inserted into a vein and advanced to the heart to observe how the heart is functioning)

- Echocardiogram or ultrasound imaging of the heart

- Magnetic resonance imaging (MRI), a test that produces very clear pictures, or images, of the human body with a large magnet, radio waves, and a computer

Double inlet left ventricle treatment

Surgery is needed to improve blood circulation through the body and into the lungs. The most common surgeries to treat DILV are a series of two to three operations in order to make the heart work effectively. These surgeries are similar to the ones used to treat hypoplastic left heart syndrome and tricuspid atresia. With surgery, blood circulation through the body and into the lungs can be improved. In most cases, the heart can be repaired to the point where the child can lead a relatively normal life.

Surgeries most commonly performed to treat double inlet left ventricle lead up to a surgery called the Fontan procedure. If blood flow to the pulmonary artery is restricted, a small tube called a shunt can be surgically placed from an artery attached to the aorta to the pulmonary artery. If there is too much blood flow to the lungs, the surgeon may perform a pulmonary artery banding, which protects the pulmonary arteries from high blood pressure.

The first surgery may be needed when the baby is only a few days old. In most cases, the baby can go home from the hospital afterward. The child will most often need to take medicines every day and be closely followed by a pediatric heart doctor (cardiologist). A pediatric cardiologist will determine when the second stage of surgery should be done.

The next surgery (or first surgery, if the baby didn’t need a procedure as a newborn) is called the bidirectional Glenn shunt or Hemi-Fontan procedure. This surgery is usually done when the child is 4 to 6 months old.

Even after the above operations, the child may still look blue (cyanotic). The final step is called the Fontan procedure. This surgery is most often done when the child is 18 months to 6 years old. After this final step, the baby no longer will have blue skin. The Fontan procedure has risks and complications, which your child’s doctor will discuss with you.

The Fontan operation does not create normal circulation in the body. But, it does improve blood flow enough for the child to live and grow.

A child may need more surgeries for other defects or to extend survival while waiting for the Fontan procedure.

Your child may need to take medicines before and after surgery. These may include:

- Anticoagulants to prevent blood clotting

- ACE inhibitors to reduce blood pressure

- Digoxin to help the heart contract

- Water pills (diuretics) to remove extra fluid from the body and reduce swelling in the body

In addition, children with double inlet left ventricle have to take antibiotics before dental treatment in order to prevent endocarditis (infection of the heart lining).

A heart transplant may be recommended, if the above methods fail.

Double inlet left ventricle prognosis

Double inlet left ventricle is a very complex heart defect that isn’t easy to treat. How well the baby does depends on:

- The baby’s overall condition at the time of diagnosis and treatment.

- If there are other heart problems.

- How severe the defect is.

- Genetic syndromes.

After treatment, many infants with double inlet left ventricle live to be adults. But, they will require lifelong follow-ups. They may also face complications and may have to limit their physical activities.

Double inlet left ventricle survival rate

Double inlet left ventricle is a very complex heart defect that isn’t easy to treat. How well the baby does depends on:

- The baby’s overall condition at the time of diagnosis and treatment.

- If there are other heart problems.

- How severe the defect is.

- Genetic syndromes.

Early mortality has decreased to 3% and survival is 97 and 88% at 5 and 10 years after surgery, respectively 2. Actuarial survival for the 203 early operative survivors at 5, 10, 15, and 20 years was 91%, 80%, 73%, and 69%, respectively. Forty-nine percent (99 of 203) had additional surgical procedures after the Fontan operation. Other frequent late events were atrial flutter or fibrillation (57%), protein-losing enteropathy (9%), and thromboembolic events (6%) 2. Current health status was described as good or excellent by 84% of patients, fair by 18%, and poor by 12% 2.

References- Gidvani M, Ramin K, Gessford E, Aguilera M, Giacobbe L, Sivanandam S. Prenatal diagnosis and outcome of fetuses with double-inlet left ventricle. AJP Rep. 2011;1(2):123-128. doi:10.1055/s-0031-1293515 https://www.ncbi.nlm.nih.gov/pmc/articles/PMC3653524

- Earing M G, Cetta F, Driscoll D J. et al.Long-term results of the Fontan operation for double-inlet left ventricle. Am J Cardiol. 2005;96:291–298. https://doi.org/10.1016/j.amjcard.2005.03.061