Duodenal atresia

Duodenal atresia is a condition that occurs when a portion of the duodenum doesn’t form. Duodenal atresia results in a blockage (atresia) that stops food or fluid from leaving the baby’s stomach. Duodenal atresia is a congenital (present at birth) intestinal obstruction in the form of complete obliteration of the duodenal lumen that can cause bilious or nonbilious vomiting within the first 24 to 38 hours of neonatal life, typically following the first oral feeding 1. A duodenal diaphragm or duodenal web is thought to represent a mild form of duodenal atresia. Duodenal atresia is associated with in-utero polyhydramnios and is one of the most common causes of fetal bowel obstruction. Antenatal ultrasound can make the diagnosis. If duodenal atresia is not diagnosed antenatally, then the diagnosis can be made radiographically with plain abdominal x-ray as the first step in evaluation. This may be followed by a controlled contrast exam if needed. Either barium for a limited upper gastrointestinal series or water/pedialyte for an ultrasound evaluation can be performed to confirm the diagnosis. CT plays a limited if any role in the evaluation of duodenal atresia 2.

In utero, duodenal atresia, a proximal gastrointestinal tract obstruction, causes polyhydramnios by interfering with the gastrointestinal absorption of amniotic fluid swallowed by the fetus distal to the level of intestinal obstruction. Polyhydramnios is defined as abnormally large amounts of amniotic fluid in the gestational sac during pregnancy. Antenatal ultrasound is diagnostic for polyhydramnios when the amniotic fluid index is greater than 25 cm or when the total amniotic fluid is estimated to be greater than 1500 to 2000 ml. In duodenal atresia, amniotic fluid that is swallowed by the fetus is prevented from moving distally to be absorbed by the fetal gastrointestinal tract and transferred to the maternal circulation through the placenta. Rather it is refluxed back into the amniotic fluid.

Congenital duodenal atresia is one of the more common intestinal anomalies treated by pediatric surgeons, occurring 1 in 2500-5000 live births. Duodenal atresia is often associated with other anomalies, including trisomy 21/Down syndrome and cardiac malformations. In 25-40% of of children with duodenal atresia have Down syndrome or trisomy 21 3. There is a 3% prevalence of congenital duodenal atresia among patients with trisomy 21 or Down syndrome. There is no difference in prevalence between the genders. There is an association with VACTERL (vertebral defects, anal atresia, cardiac defects, tracheo-esophageal fistula, renal anomalies, and limb abnormalities), annular pancreas, and other bowel atresias including jejunal atresia, ileal atresia, and rectal atresia 4.

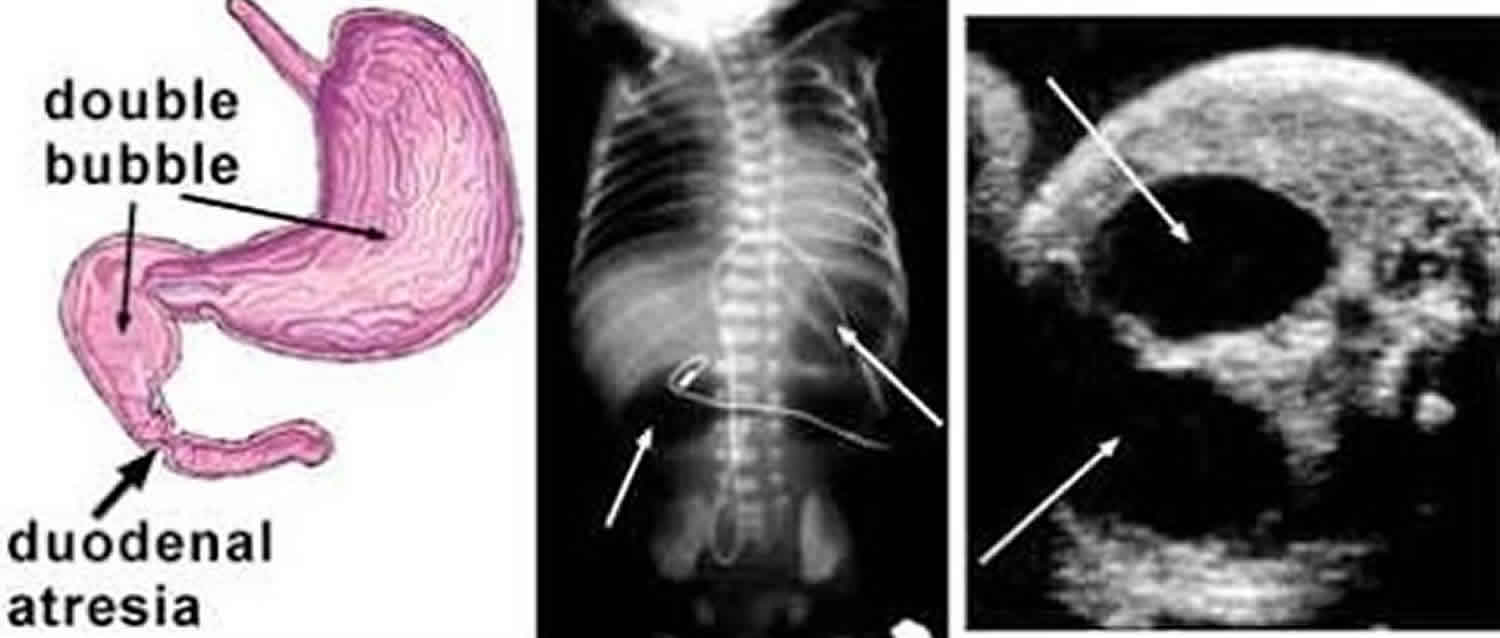

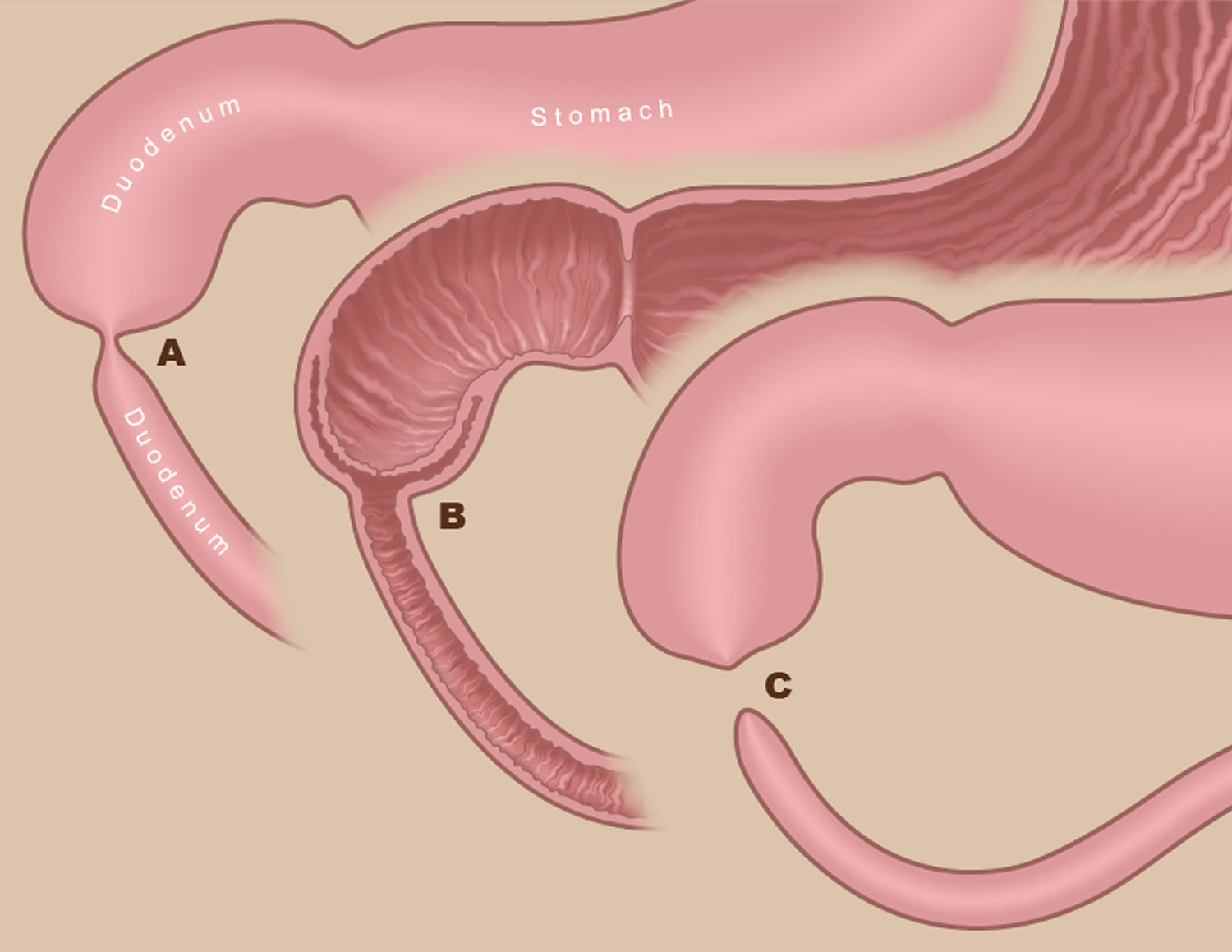

Figure 1. Duodenal atresia

Footnote: (A) Incomplete obstructions are known as duodenal “webs” because of the web-like membrane that forms inside the duodenum at the point of the obstruction (B). (C) Complete duodenal atresia occurs when a segment of the duodenum is absent.

Duodenal atresia causes

Duodenal atresia is a congenital condition, which means it develops before birth. Exactly what causes the condition is unknown, although genetics may play a role in rare cases. Duodenal atresia is believed to occur because of failure of the epithelial solid cord to recanalize or excessive endodermal proliferation 5. In duodenal atresia, there is complete obstruction of the duodenal lumen. Obstruction of the duodenum causes duodenal atresia; usually distal to the ampulla of Vater in the second portion of the duodenum. Errors of duodenal re-canalization during the eighth to the tenth week of embryological development is the main cause of duodenal atresia 1. Duodenal stenosis is the term used for narrowing resulting in an incomplete obstruction of the duodenum lumen. A duodenal web is a rarer cause of duodenal obstruction which tends to cause a windsock deformity of the duodenal lumen 6.

Duodenal atresia symptoms

Symptoms of duodenal atresia include:

- Upper abdominal swelling (sometimes)

- Early vomiting of large amounts, which may be greenish (containing bile)

- Continued vomiting even when infant has not been fed for several hours

- No urination after first few voidings

- No bowel movements after first few meconium stools

Duodenal atresia presents early in life as vomiting; which usually occurs within the first 24 to 38 hours of life after the first feeding and progressively worsens if not treated. Sometimes the vomiting may be projectile; which like pylorospasm and gastroesophageal reflux, may simulate hypertrophic pyloric stenosis 7. The clinical presentation of bilious vomiting points to congenital intestinal obstruction distal to the ampulla of Vater. There are cases of atresia proximal to the ampulla of Vater that present without bilious vomiting. The ampulla of Vater is located in the second or descending portion of the duodenum. Excessive bilious vomiting can cause hypokalemic hypochloremic metabolic alkalosis with paradoxical aciduria, particularly if there is a delay in hydration. Patients have symptoms of abdominal distension and absent bowel movements.

Duodenal atresia diagnosis

Duodenal atresia is diagnosed by ultrasound, but not usually at the routine 20-week screening ultrasound. That’s because signs of the condition tend not to be visible by ultrasound until later in the pregnancy.

Antenatal imaging will show a double bubble, an echoless stomach filled with amniotic fluid, as well as a second nearby but more distal fluid filled, often circular (but blind ended) structure (the second bubble) that is the obstructed portion of the duodenum. The diagnosis is further established if the ultrasound image shows the classic sign of duodenal atresia: a “double bubble” in the baby’s abdomen (Figure 2). The use of prenatal ultrasound has allowed for an earlier diagnosis of duodenal atresia. An advantage of neonatal abdominal ultrasound is that it can be performed in the neonatal intensive care unit or nursery. When antenatal ultrasound is performed the duodenum is usually not filled with fluid, and the presence of a fluid-filled duodenum suggests duodenal atresia. If a double-bubble sign is seen on antenatal ultrasound, then it is important for the sonographer to demonstrate a connection between the two fluid-filled structures because foregut duplication cyst, as well as other abdominal cysts, may simulate the appearance of a double-bubble sign 8.

The ultrasound that leads to the diagnosis usually occurs through one of the following two pathways:

- If genetic screening or other diagnostic testing determines the baby is at an increased risk for Down syndrome, an ultrasound will be performed to screen for duodenal atresia.

- In pregnancies with no increased risk for Down syndrome, an ultrasound will be ordered if the uterus measures large for dates in the third trimester. An enlarged uterus is sometimes caused by excessive amounts of amniotic fluid, a condition known as polyhydramnios. Extra amniotic fluid can accumulate when the unborn baby is having difficulty swallowing — a difficulty that can result from the presence of a duodenal atresia.

The initial postnatal radiographic evaluation for diagnosing duodenal atresia is a plain abdominal x-ray. In duodenal atresia, there is gas in the stomach and the proximal duodenum but an absence of gas distally in the small or large bowel. A plain abdominal x-ray may reveal the double-bubble sign which is seen postnatally as a large radiolucent (air-filled) stomach usually in the normal position to the left of the midline, and a smaller more distal bubble to the right of midline which represents a dilated duodenum. A double-bubble sign on an abdominal x-ray is a reliable indicator of duodenal atresia. Other causes of intestinal obstruction may simulate a double-bubble sign. Annular pancreas is the second most common cause of duodenal atresia. Jejunal or more distal obstruction may have dilation more distally or more than two bubbles may be present 9.

In patients with Down syndrome, the x-ray double-bubble has a higher positive predictive value because the prevalence of duodenal atresia in Down syndrome is much higher than in the general population and further evaluation with additional modalities is not always needed before proceeding to surgery. Duodenal stenosis can also cause the double-bubble sign; however, if stenosis is present, at least a small amount of gas may be present distal to the obstruction. The absence of gas in the stomach on abdominal x-ray is a sign of esophageal atresia without tracheoesophageal fistula. At times there may be distal air distal to a duodenal atresia that has entered distal bowel via an anomalous biliary tree. The radiographic appearance of the double-bubble sign should prompt immediate surgical consultation. For cases of suspected duodenal atresia not identified antenatally, barium fluoroscopy can be used to assess the gastrointestinal tract. If necessary further evaluation with ultrasound or upper gastrointestinal series may be performed. More recently, neonatal ultrasound has been shown to be very helpful in clarifying the anatomy, especially using the fluid as a contrast agent 10. A possible mimic of the double-bubble sign is the pseudo-double-bubble sign created by the curved configuration of the stomach where the two bubbles represented normal fluid in the proximal the and distal stomach.

Barium contrast is administered sometimes via an orogastric or nasogastric tube under fluoroscopy to evaluate the esophagus, stomach, and duodenum. Only a controlled amount of barium is placed to confirm obstruction. It is then removed by nasogastric tube to prevent reflux and potential aspiration. The main purpose of the upper gastrointestinal series is to differentiate between duodenal atresia and midgut volvulus; an important distinction, because midgut volvulus requires emergency surgery, whereas duodenal atresia can be managed on an urgent basis 11.

Pediatric CT plays a very limited if any role in diagnosis and evaluation of duodenal atresia. However, its 2D reconstruction may allow for further evaluation of bowel layout in confusing cases. Neonatal CT is more technically challenging as it may require sedation, bundling and, starting a neonatal intravenous line for contrast administration. Additionally, CT does involve ionizing radiation and may be more difficult to interpret because there is less abdominal fat separating abdominal viscera compared to older patients.

Figure 2. Duodenal atresia showing double bubble sign on ultrasound

Footnote: Ultrasound showed “double bubble sign” with polyhydramnios. One “bubble” is the fluid-filled stomach; the other is the fluid-filled duodenum. Those “bubbles” mean that, due to the atresia (blockage), there is fluid in the stomach and in part of the duodenum, but not further down the intestinal tract.

Figure 3. Duodenal atresia X-ray

Footnote: Marked gaseous distension of the stomach and proximal duodenum, with absent bowel gas distally. Typical “double bubble” appearance of duodenal atresia. The baby had an unremarkable antenatal course, and the diagnosis was not expected at birth. Baby recovered well following repair of duodenal atresia.

Duodenal atresia treatment

The prenatal management of babies with duodenal atresia starts with acquiring as much information about the condition as early as possible. Tests will also be done to help determine if Down syndrome or a heart-related birth defect are present. To gather all of that information, doctors use several different techniques, including high-resolution fetal ultrasonography, fetal echocardiography and amniocentesis.

Duodenal atresia cannot be treated before a child is born. Doctors will, however, take an active, two-fold approach to managing the condition during your pregnancy. First, your doctor will monitor both mother and baby very carefully, looking for any potential complications that might lead to premature delivery. One of those potential complications is the accumulation in the uterus of extra amniotic fluid (polyhydramnios), which can occur when the atresia (blockage) makes it difficult for the baby to swallow. If this happens, doctors will watch closely for signs of preterm labor and/or symptoms in the mother related to the increased uterine size and pressure. Occasionally, an amnioreduction is performed. This procedure, which is similar to an amniocentesis, removes some of the excess fluid and alleviates any symptoms the mother may be experiencing.

Second, doctors will try to identify any complicating factors — such as Down syndrome or a heart defect — that might require additional therapies. That way your doctors can be prepared during and after delivery to optimally care for your infant.

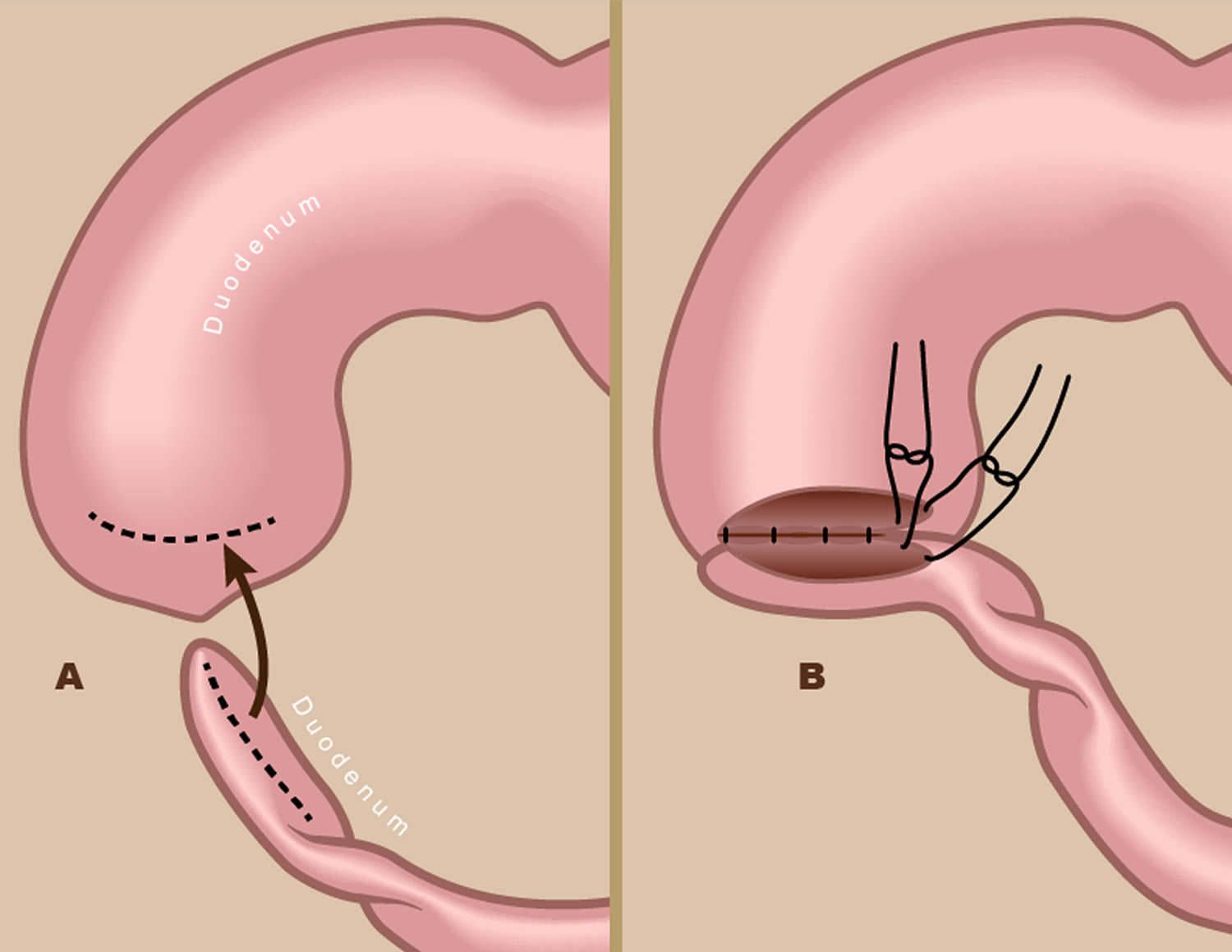

Infants with duodenal atresia can be delivered vaginally. The goal will be to have your baby’s birth occur as near to your due date as possible. Treatment involves nasogastric suction to decompress the stomach and surgery to correct the obstructing lesion. Duodenoduodenostomy is the typical surgery performed. Doudenodoudenostomy can be performed as an open or laparoscopic procedure. Doudenodoudenostomy is a type of bypass procedure that is said to be technically demanding for a laparoscopic approach. A diamond-shaped anastomosis is constructed with a proximal transverse to the distal longitudinal duodenal anastomosis. The bypass procedure avoids damage to the pancreas, main pancreatic duct, accessory pancreatic duct, and common bile duct. Before surgery, the stomach and proximal duodenum are decompressed with an orogastric tube, and intravenous fluid resuscitation is performed. Possible complications of duodenoduodenostomy include gastroesophageal reflux, megaduodenum, and impaired duodenal motility. A complete operative evaluation includes looking for additional areas of intestinal obstruction 12.

Duodenal atresia surgery

Treatment for duodenal atresia requires an operation to remove the blockage (atresia) and repair the duodenum. The surgery is not considered an emergency, and is typically done when the baby is two or three days old.

Surgical treatment for duodenal obstruction includes some different techniques for the intrinsic causes, including duodeno-duodenostomy and duodeno-jejunostomy. A duodenoduodenostomy is the most commonly performed procedure. A duodenojejunostomy is now uncommonly performed due to its higher risk of long-term complications.

Although there are several subtypes of duodenal atresia, the surgical procedure is basically the same for all of them. The surgeon opens up the blocked end of the duodenum and then connects it to the rest of the small intestine. The surgeon will also pass a tube from your baby’s mouth through the stomach and into the small intestine. This “feeding tube” will be used for the first few weeks after surgery.

The surgery is done under general anesthesia. Afterward, your baby will be returned to the newborn intensive care unit (NICU). For several days, your baby may need a machine (ventilator) to help with breathing.

With surgical correction, prognosis is excellent (especially with isolated cases), and the outlook is therefore largely determined by other associated abnormalities.

Figure 4. Duodenal atresia surgery

Footnote: During surgery to repair duodenum atresia, the surgeon opens up the blocked ends of the duodenum (A) and then sutures them together (B).

How long will my baby be in the hospital?

Typically, your baby will be in the hospital for two to three weeks. The feeding tube inserted during surgery will be kept in place until the small intestine has healed, a process that can take up to two weeks. During the healing process, your baby can be fed breast milk or formula through the feeding tube placed during surgery. Once the healing is confirmed, the baby can start nursing or receiving a bottle.

Your baby will be discharged from the hospital when he or she is taking food by mouth without difficulty and gaining weight.

Duodenal atresia prognosis

The prognosis for babies with isolated duodenal atresia is excellent when the condition is diagnosed and treated promptly.

Most babies with isolated duodenal atresia do not require long-term follow-up. Such follow-up may be necessary, however, for babies with the condition who also have Down syndrome and/or a heart defect. These children may also require more surgery and hospitalization.

Over the past three decades, the mortality rates of duodenal atresia have significantly dropped averaging 2-5%. Mortality rates are not directly related to the surgery but to the other associated organ anomalies like complex congenital cardiac defects. However, survival continues to improve with better NICU (newborn intensive care unit) care, nutritional support and improved pediatric anesthesia. Today long-term survival of most infants (more than 80%) with duodenal atresia is the norm.

Duodenal atresia complications

Complications are chiefly associated with surgery and include the following:

- Megaduodenum

- Blind loop syndrome

- Cholecystitis

- Esophagitis

- Peptic ulcer disease

- Gastroesophageal reflux disease (GERD)

- Pancreatitis

- Gossman W, Eovaldi BJ, Cohen HL. Duodenal Atresia And Stenosis. [Updated 2019 May 19]. In: StatPearls [Internet]. Treasure Island (FL): StatPearls Publishing; 2019 Jan-. Available from: https://www.ncbi.nlm.nih.gov/books/NBK470548

- Srisajjakul S, Prapaisilp P, Bangchokdee S. Imaging spectrum of nonneoplastic duodenal diseases. Clin Imaging. 2016 Nov – Dec;40(6):1173-1181.

- Freeman SB, Torfs CP, Romitti PA, et al. Congenital gastrointestinal defects in Down syndrome: a report from the Atlanta and National Down Syndrome Projects. Clin Genet. 2009 Feb. 75(2):180-4.

- Morris JK, Springett AL, Greenlees R, Loane M, Addor MC, Arriola L, Barisic I, Bergman JEH, Csaky-Szunyogh M, Dias C, Draper ES, Garne E, Gatt M, Khoshnood B, Klungsoyr K, Lynch C, McDonnell R, Nelen V, Neville AJ, O’Mahony M, Pierini A, Queisser-Luft A, Randrianaivo H, Rankin J, Rissmann A, Kurinczuk J, Tucker D, Verellen-Dumoulin C, Wellesley D, Dolk H. Trends in congenital anomalies in Europe from 1980 to 2012. PLoS ONE. 2018;13(4):e0194986

- Prasad TR, Bajpai M. Intestinal atresia. Indian J Pediatr. 2000 Sep;67(9):671-8.

- Sheorain VK, Cohen HL, Boulden TF. Classical wind sock sign of duodenal web on upper gastrointestinal contrast study. J Paediatr Child Health. 2013 May;49(5):416-7.

- Gilet AG, Dunkin J, Cohen HL. Pylorospasm (simulating hypertrophic pyloric stenosis) with secondary gastroesophageal reflux. Ultrasound Q. 2008 Jun;24(2):93-6.

- Koberlein G, DiSantis D. The “double bubble” sign. Abdom Radiol (NY). 2016 Feb;41(2):334-5.

- Blumer SL, Zucconi WB, Cohen HL, Scriven RJ, Lee TK. The vomiting neonate: a review of the ACR appropriateness criteria and ultrasound’s role in the workup of such patients. Ultrasound Q. 2004 Sep;20(3):79-89.

- Cohen HL, Moore WH. History of emergency ultrasound. J Ultrasound Med. 2004 Apr;23(4):451-8.

- Latzman JM, Levin TL, Nafday SM. Duodenal atresia: not always a double bubble. Pediatr Radiol. 2014 Aug;44(8):1031-4.

- Oh C, Lee S, Lee SK, Seo JM. Laparoscopic duodenoduodenostomy with parallel anastomosis for duodenal atresia. Surg Endosc. 2017 Jun;31(6):2406-2410.