Epulis

Epulis literally means “of the gums”, is a benign inflammatory tumor of the gingiva (gums) and develops in response to a local chronic irritative factor (brackets, tartar, and interdental spaces) 1. However, some authors define epulis as a non-specific term used for tumors and tumor-like masses of the gingiva (gums) 2. Therefore, the classification and terminology of epulis are conflicting in the literature.

In 2004, Sapp divided epulis into four main kinds, namely, peripheral fibroma, peripheral ossifying fibroma, pyogenic granuloma (including pregnancy tumour) and peripheral giant cell granuloma, based on the histological feature 3. However, other literature classified epulis into acanthomatous epulis, giant-cell epulis, ossifying epulis and periodontal fibromatous epulis. In 2008, the Dental Dictionary categorized epulis into congenital of newborn, epulis fissuratum, epulis-giant cell, and epulis granulomatosa. Furthermore, some categorizsation was also based on the age group. These different classifications result in the confusing diagnoses and treatments.

Epulis occurs twice as often in women than in men.

The cause of epulis is multifactorial like irritative factors (poor oral hygiene, chronic gingivitis, periodontal diseases) and hormonal changes.

Epulis are usually divided into 3 types i.e. epulis fissuratum (fibrous epulis), giant-cell epulis and congenital epulis. Epulis fissuratum (fibrous epulis) most commonly occurs at the anterior gingival region. It may be pinkish in color, sessile or pedunculated, fixed but elastic in consistency, covered by apparently health mucous tissue unless the surface has been injured or ulcerated. Areas of fibrous epulis can resemble fibrous dysplasia or ossifying fibroma but the distinction from such bone lesions is readily made by the clinically peripheral location of the fibrous epulis which does not arise from bone. Histopathologically the lesion consists of hyperplastic connective tissue, can be ulcerated and covered by stratified squamous epithelium.

Table 1. Epulis types

| Epulis type | Description |

|---|---|

| Epulis fissuratum | Overgrowth of fibrous connective tissue around the edges of ill-fitting dentures |

| Giant-cell epulis | A peripheral giant cell granuloma that arises exclusively from the periodontal ligament enclosing the root of a tooth |

| Congenital epulis | Rare tumor of the newborn that arises from the mucosa of the gingiva |

According to histological analysis and cause, epulis are classified as: epulis gigantocellularis, epulis fibromatosa, epulis congenita, epulis gravidarum, epulis granulomatosa, epulis fissuratum, epulis hemangiomatosa 5.

Clinically, epulis appears as a localized nodule appearing on the marginal gingiva or alveolar processes. It is difficult to clinically distinguish epulis from malignant tumors or any other lesion on the gingiva, and a histopathological analysis is essential for diagnosis.

Histological examination of epulides indicates that the vast majority are the fibrous hyperplasias, peripheral ossifying fibromas, epulis gigantocellularis, epulis granulomatosa, epulis fissuratum,

epilis gravidarum, epulis haemangiomatosa.

The treatment of epulis is to remove the causal factors and surgical excision of the lesion.

Inflammatory epulis is most common following orthodontic treatment. Its size can be significant. Highly vascularized, it bleeds easily. Its treatment is based on excision up to the bone contact, removal of the causal factor if possible, and oral hygiene reeducation. In children, the presence of an inflammatory epulis requires a complete blood count (CBC) to rule out leukemia 1.

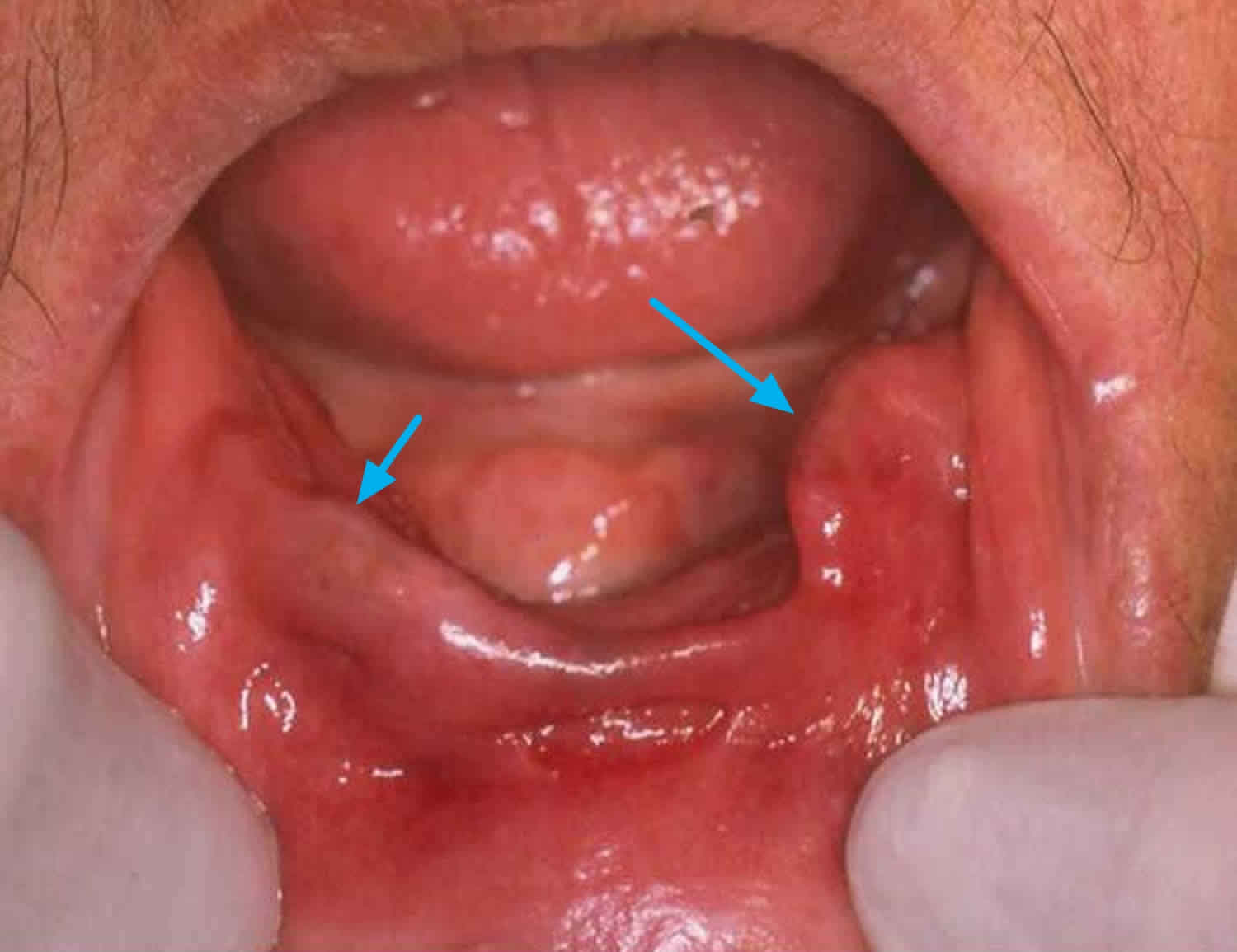

Figure 1. Epulis

[Source 6 ]Epulis fissuratum

Epulis fissuratum is also referred to as inflammatory fibrous hyperplasia, fibromatous epulis, denture epulis and denture-induced fibrous hyperplasia 4. The fibrous overgrowth is caused by chronic irritation of the denture flange (edge) against the area where the gums meet the inner cheek (alveolar vestibular mucosa). Because bone under the denture is constantly changing due to bone loss, the bony support for the denture base becomes unstable which results in ill-fitting dentures and epulis fissuratum.

Clinically, this adaptive lesion presents a raised sessile lesion in a form of folds, with a smooth surface and normal mucosa coloration.2 Depending on the intensity of the trauma, the surface may become ulcerated. The definitive treatment is excision with appropriate prosthetic reconstruction. Recurrences are rare as long as the sources of trauma and/or the patient’s habits are eliminated and the appropriate prosthetic rehabilitation is provided 7.

Epulis fissuratum is most common in the elderly as the need for dentures increases with age. However, it is becoming less of a problem nowadays as dental technology to maintain and restore teeth is much more advanced. Epulis fissuratum appears to be more common in women than men.

Figure 2. Epulis fissuratum

Footnote: Clinical presentation of a lower epulis fissuratum without protheses.

[Source 8 ]Epulis fissuratum signs and symptoms

Epulis fissuratum is not a true tumor but an adaptive fibroepithelial response due a chronic low-grade irritation from poorly adapted prostheses with variable degrees of hypertrophy and hyperplasia.

The lesions made up of excess tissue are usually firm, fibrous and pink. One part of the lesion is found under the denture while the rest protrudes into the cheek area. The internal and external parts of the lesion are separated by a deep groove in which the denture flange sits. Sometimes the irritation can be severe enough to cause redness and ulceration, particularly at the bottom of the groove where the denture rests.

Epulis fissuratum treatment

The lesions of epulis fissuratum can be surgically cut out. Although it is very uncommon for these lesions to be associated with oral squamous cell carcinoma, as a precautionary measure the removed lesion should be sent for microscopic testing.

In addition to removing lesions, dentures should be re-modelled to fit properly into the gums to prevent further irritation and development of epulis fissuratum.

Giant cell epulis

Giant cell epulis is also referred to as granulomatous epulis, peripheral giant cell granuloma, giant cell reparative granuloma, osteoclastoma and myeloid epulis 4, gingival pyogenic granuloma 9, lobular capillary hemangioma of the gingiva 10 and epulis granulomatosa 11. It is not clear why lesions of giant cell epulis occur but it may be a response to injury. In addition, many cases have cells expressing surface receptors for estrogen, which has led to speculation that hormonal influences may play a role in their development.

Giant cell epulis or granulomatous epulis may occur at any time, although it appears to be most commonly diagnosed between 40-60 years of age. In adults it occurs mainly in women.

Local irritants, such as calculus, hormonal factors, certain drugs, and poor oral hygiene, may contribute to the development of granulomatous epulis 9. The management of granulomatous epulis depends on the clinical manifestations. Removal of the causative irritants, clinical observation and follow-up may be suggestive when the lesion is small, painless and free of bleeding. Although conservative excision, which extends down to the periosteum and reserves the teeth, was the usual treatment, invasive resection, which includes removing the adjacent teeth, should be performed to treat the extensive lesion with serious loose tooth or the recurrent lesion 10.

Giant cell epulis signs and symptoms

Lesions are often fibrous and present as a gingival lump emerging between two teeth. The lesion grows quickly and may exceed 4cm in diameter, but most remain less than 2cm. It can grow into an irregular red fleshy mass that may ulcerate or bleed. Sometimes the giant cell epulis may invade underlying bone.

Giant cell epulis treatment

Treatment involves surgical excision of the lesion and curettage of any underlying bony defect. The affected teeth may also need to be extracted or scaling and root planing performed. A recurrence rate of 10% or more has been reported and re-excision may be required.

However, other clinicians recommend to conserve the teeth in consideration of the aesthetics or masticatory function 12. Recently, more treatment protocols, including laser surgery and cryosurgery, were used to deal with granulomatous epulis to reserve the teeth and reduce recurrence 10.

Each protocol has its advantages. However, incomplete excision 13, continuous secretion of hormone and remaining irritation could also cause the recurrence 10 even in some cases with teeth extraction. In this series 3, the patients with recurreding granulomatous epulis were all female between 15 and 38-years-old; some patients even had the involved teeth removed. This evidence indicated that hormonal reason may play a critical role in these cases. Furthermore, if surgery is still the treatment of choice to treat, then more extensive resection should be performed, including the removal of more teeth and alveolar bone, which were not accepted by most patients. More important was that more extensive surgery could not confirm success.

In the present cases 3, the intralesional intralesional pingyangmycin injection was used for the relapsed lesions. The exciting result indicated that intralesional pingyangmycin sclerotherapy may be an additional method for the granulomatous epulis.

Congenital epulis

Congenital epulis is also referred to as congenital (present at birth) granular cell myoblastoma, congenital granular cell epulis, granular cell epulis of infancy, and granular cell fibroblastoma 4. It is not clear why congenital epulis occur but they are thought to originate from primitive mesenchymal cells of neural crest origin.

This is a rare congenital condition that appears at birth. Congenital epulis occurs much more commonly in female than males with a ratio of approximately 9–10:1 and because of this gender-specific predominance and its in utero origins, it has been theorized that the development of the congenital epulis may be closely linked to maternal hormones 14.

Typically, the growth of the epulis manifests during the third trimester of pregnancy and completely arrests after birth 14. As a result, the presence of the lesion has the potential to hinder proper breast feeding in newborns and is often resolved via surgical excision. Frequently, congenital epulis is detected in utero via the use of antepartum ultrasound or magnetic resonance imaging 15.

Congenital epulis is usually an isolated finding without association with any syndromes or genetic abnormalities 16. Congenital epulis predominantly occurs as a solitary lesion, while multiple lesions are seen in 10% of the cases 14. In multifocal cases, the lesions often involve both maxilla and mandible 17. Congenital epulis usually ranges from 1 to 2 cm in diameter, although larger masses up to 9 cm have been previously reported 18. Clinically, it presents as a well-circumscribed, sessile or pedunculated lesion with a smooth, normal-colored surface (Figure 3) 16.

Figure 3. Congenital epulis

Footnote: Congenital epulis is characterized by a well-circumscribed lesion on the anterior alveolar ridge of a newborn infant showing a pink, smooth, and glistening external surface.

[Source 19 ]Congenital epulis signs and symptoms

Infants are born usually with a mass protruding out their mouth. The lesion is almost exclusively found on the anterior alveolar ridges of the newborn. In 10% of cases multiple lesions may be present. Lesions may range from 0.5 to 2cm in size, and in rare cases reach up to as much as 9cm. The lesion is a soft, pedunculated and sometime lobulated nodule of the alveolar mucosa.

If the epulis is too large it may interfere with breathing and feeding.

Congenital epulis treatment

Most congenital epulis tend to spontaneously regress and disappear over the first 8 months of life 4. Hence, if the lesion is small there may be no need for treatment. Larger lesions that may interfere with breathing and/or feeding may need to be surgically removed. Carbon dioxide laser has been used successfully to remove large lesions. Recurrences of epulis have not been reported and residual remnants appear not to interfere with tooth eruption.

Congenital epulis prognosis

Congenital epulis has an excellent prognosis with simple excision as the mainstay curative treatment 14. Conservative monitoring is also acceptable in patients with smaller lesions as congenital epulis occasionally regresses spontaneously 16. Recurrence after resection is uncommon and there has not been report of malignant transformation 14.

Epulis causes

There are three existing theories in the cause of epulis 6. The first is that epulis occurs as an inflammatory response to local stimuli (unadjusted prosthetic, improper fillings, residual roots, poor oral hygiene and various other trauma). Cells of the mucoperiosteum respond to such stimuli by forming a specific granulation tissue.

Second theory suggests a benign neoplasm.

A third theory holds that hormonal imbalance related to pregnancy or hyperparathyroidism act as the cause of epulis 20.

Most commonly, epulis is a reactive hyperplasia of the connective tissue of the gingiva or the periodontal ligament 6.

Epulis diagnosis

No clinical laboratory tests are used for these lesions. A definitive diagnosis requires biopsy.

Conservative excisional biopsy is indicated because both lesions are rarely larger than 2 cm in diameter. As a general rule, the depth of biopsy for granular cell tumors approximates the diameter of the lesion. Margins do not need to be extensive; generally, a few millimeters is adequate.

The depth of biopsy for congenital epulis is the periosteum. Removal of bone is not indicated. Since these are exophytic lesions, surgical margins do not need to be much greater than the clinical margins.

Epulis treatment

Treatment for epulis depends on the type. For examplae, for granular cell tumors and congenital epulis treatment is surgery. While extensive surgery is not indicated, recurrence of granular cell tumors has been reported several years after removal. Recurrence of congenital epulis has not been reported; however, the number of total cases is small. If congenital epulis is asymptomatic and surgery is deferred, the lesion may regress spontaneously 21.

References- Sicard, L. & Benmoussa, L. & Moreau, Nathan & Salmon, Benjamin & Anne-Laure, Ejeil. (2018). Orthodontics and oral mucosal lesions in children and teenagers. Journal of Dentofacial Anomalies and Orthodontics. 21. 207. 10.1051/odfen/2018056

- Fibrous Epulis in a child. International Journal of Clinical & Medical Images (2014) Volume 1, Issue 7 http://dx.doi.org/10.4172/ijcmi.1000233

- Cai Y, Sun R, He KF, Zhao YF, Zhao JH. Sclerotherapy for the recurrent granulomatous epulis with pingyangmycin. Med Oral Patol Oral Cir Bucal. 2017;22(2):e214–e218. Published 2017 Mar 1. doi:10.4317/medoral.21422 https://www.ncbi.nlm.nih.gov/pmc/articles/PMC5359704

- Epulis. https://dermnetnz.org/topics/epulis

- Kamath KP, Vidya M, Anand PS. Biopsied lesions of the gingiva in a southern Indian population – a retrospective study. Oral Health Prev Dent. 2013;11(1):71-9.

- Hadžić S, Gojkov-Vukelić M, Pašić E. (2015). DIAGNOSTIC AND THERAPEUTIC PROTOCOL WITH HISTOPATHOLOGIC ANALYSIS OF GINGIVAL EPULIS: REPORT OF TWO CASES. Stomatolos̆ki vjesnik. Stomatological review. 4 (2). 107-111.

- M. Tamarit-Borrás, E. Delgado-Molina, L. Berini-Aytés, C. Gay-Escoda. Removal of hyperplastic lesions of the oral cavity. A retrospective study of 128 cases. Med Oral Patol Oral Cir Bucal, 10 (2005), pp. 151-162

- Treatment of epulis fissuratum with carbon dioxide laser. Rev port estomatol med dent cir maxilofac. 2011;52(3):165–169 DOI: 10.1016/j.rpemd.2011.05.001

- Gomes SR, Shakir QJ, Thaker PV, Tavadia JK. Pyogenic granuloma of the gingiva: A misnomer? – A case report and review of literature. J Indian Soc Periodontol. 2013;17:514–9.

- Jafarzadeh H, Sanatkhani M, Mohtasham N. Oral pyogenic granuloma: a review. J Oral Sci. 2006;48:167–75.

- Kuhl SR, Schulze RK, Kreft A, d’Hoedt B. Epulis granulomatosa as an oral manifestation of Klippel-Trenaunay syndrome. J Oral Pathol Med. 2006;35:576–8.

- Zheng JW, Zhou Q, Yang XJ, He Y, Wang YA, Ye WM. Intralesional injection of Pingyangmycin may be an effective treatment for epulis. Med Hypotheses. 2009;72:453–4.

- Taira JW, Hill TL, Everett MA. Lobular capillary hemangioma (pyogenic granuloma) with satellitosis. J Am Acad Dermatol. 1992;27:297–300.

- Conrad R, Perez MC. Congenital granular cell epulis. Arch Pathol Lab Med. 2014;138:128–131. doi: 10.5858/arpa.2012-0306-RS

- Silva GC, Vieira TC, Vieira JC, et al. Congenital granular cell tumor (congenital epulis): a lesion of multidisciplinary interest. Med Oral Patol Oral Cir Bucal. 2007;12:E428-30

- Ritwik P, Brannon RB, Musselman RJ. Spontaneous regression of congenital epulis: a case report and review of the literature. J Med Case Rep. 2010;4:331. doi: 10.1186/1752-1947-4-331

- Bianchi PR, de Araujo VC, Ribeiro JW, et al. Multiple congenital granular cell epulis: case report and immunohistochemical profile with emphasis on vascularization. Case Rep Dent. 2015;2015:878192

- Eghbalian F, Monsef A. Congenital epulis in the newborn, review of the literature and a case report. J Pediatr Hematol Oncol. 2009;31:198–199. doi: 10.1097/MPH.0b013e31818ab2f7

- Cheung JM, Putra J. Congenital Granular Cell Epulis: Classic Presentation and Its Differential Diagnosis. Head Neck Pathol. 2020;14(1):208–211. doi:10.1007/s12105-019-01025-1 https://www.ncbi.nlm.nih.gov/pmc/articles/PMC7021869

- Carbone M, Broccoletti R, Gambino A, Carrozzo M, Tanteri C, Calogiuri PL, Conrotto D, Gandolfo S, Pentenero M, Arduino PG. Clinical and histological features of gingival lesions: a 17-year retrospective analysis in a northern Italian population. Med Oral Patol Oral Cir Bucal. 2012,17(4):555-61.

- Ruschel HC, Beilke LP, Beilke RP, Kramer PF. Congential epulis of newborn: report of a spontaneous regression case. J Clin Pediatr Dent. 2008. 33(2):167-9.