Follicular mucinosis

Follicular mucinosis also known as alopecia mucinosa, is a rare skin disorder characterized by follicular degeneration due to the accumulation of mucin within the pilosebaceous unit (hair follicle), with associated inflammatory changes 1. Follicular mucinosis describes the appearance of mucin around hair follicles as seen under the microscope. Mucins look like stringy clear or whitish goo mainly composed of hyaluronic acid, a normal component of the ground substance surrounding collagen in the dermis. Follicular mucinosis was first described by Pinkus as alopecia caused by follicular degeneration secondary to the accumulation of mucin around the outer hair sheath and sebaceous gland, with prominent follicular infiltration by chronic inflammatory cells 2. Subsequent evidence revealed that this unique degeneration of the hair follicles can occur in the presence or absence of alopecia (hair loss), hence the name follicular mucinosis 3.

Follicular mucinosis can be broadly classified into 3 different forms with variations in onset, course, and disease associations.

- The first is a primary acute form (Pinkus type) which occurs more commonly in children and adolescents, with solitary lesions seen on the head and scalp that resolve spontaneously within a relatively short period.

- The second is a primary chronic form which is seen in people older than 40 years and runs a more protracted course with multiple disseminated lesions that tend to recur frequently following treatment.

- The third variant occurs secondary to a wide range of benign diseases (lupus erythematosus, hypertrophic lichen planus, alopecia areata), hematopoietic stem cell transplantation and malignant diseases (Hodgkin’s lymphoma, leukemia cutis, cutaneous T-cell lymphoma), the most documented being mycosis fungoides 4.

- Urticaria-like follicular mucinosis (rare).

There is no known way to differentiate idiopathic follicular mucinosis from mycosis fungoides or cutaneous T-cell lymphoma-associated follicular mucinosis with certainty. In general, patients with idiopathic follicular mucinosis tend to be younger and have fewer and more localized lesions (on the head or neck). No reliable distinguishing clinical, histological, or molecular parameter exists.

Unless patients have or develop clinical and histological evidence of mycosis fungoides or cutaneous T-cell lymphoma (e.g. poikilodermatous patches, arcuate plaques on exam, cytologically atypical lymphocytes with epidermotropism histologically), it is difficult or impossible to predict which patients will progress.

Patients with follicular mucinosis require a thorough review of systems, full skin and lymph node exam, and long-term follow up. Given the association with cutaneous T-cell lymphoma, as well as much rarer associations with other hematologic malignancies (e.g. acute myeloblastic leukemia), a baseline complete blood count (CBC) with differential and lactate dehydrogenase (LDH) level should be obtained, and chest radiograph should be considered.

The pathogenesis of follicular mucinosis remains largely unknown. It has been postulated to arise from cellular alterations in the affected structures leading to the production of mucin 5. A cell-mediated immune mechanism as evidenced by a large number of T-cells and macrophages, with markedly increased number of Langerhans cells within the affected hair follicle has also been suggested to play a role 6.

Treatment modalities that have been described in the management of follicular mucinosis include topical, intralesional and systemic glucocorticoids, x-irradiation, dapsone, antimalarials, indomethacin, isotretinoin, minocycline, PUVA photochemotheraphy, and UVA1 phototheraphy 7. In cases of secondary follicular mucinosis, treatment of the underlying cause leads to resolution of symptoms. Follicular mucinosis has been reported to run a more benign course in children even when associated with mycosis fungoides, with some authors suggesting that a less aggressive approach be used in both diagnosis and treatment of this age group 8. Expectant management is an option in cases of primary follicular mucinosis as most cases resolve spontaneously within two months to two years. However, the lack of clear cut diagnostic methods and the potential association of follicular mucinosis with other more aggressive disease conditions warrant a need for constant followup usually for a minimum of five years in affected individuals to enable early detection of signs of other malignancies 4.

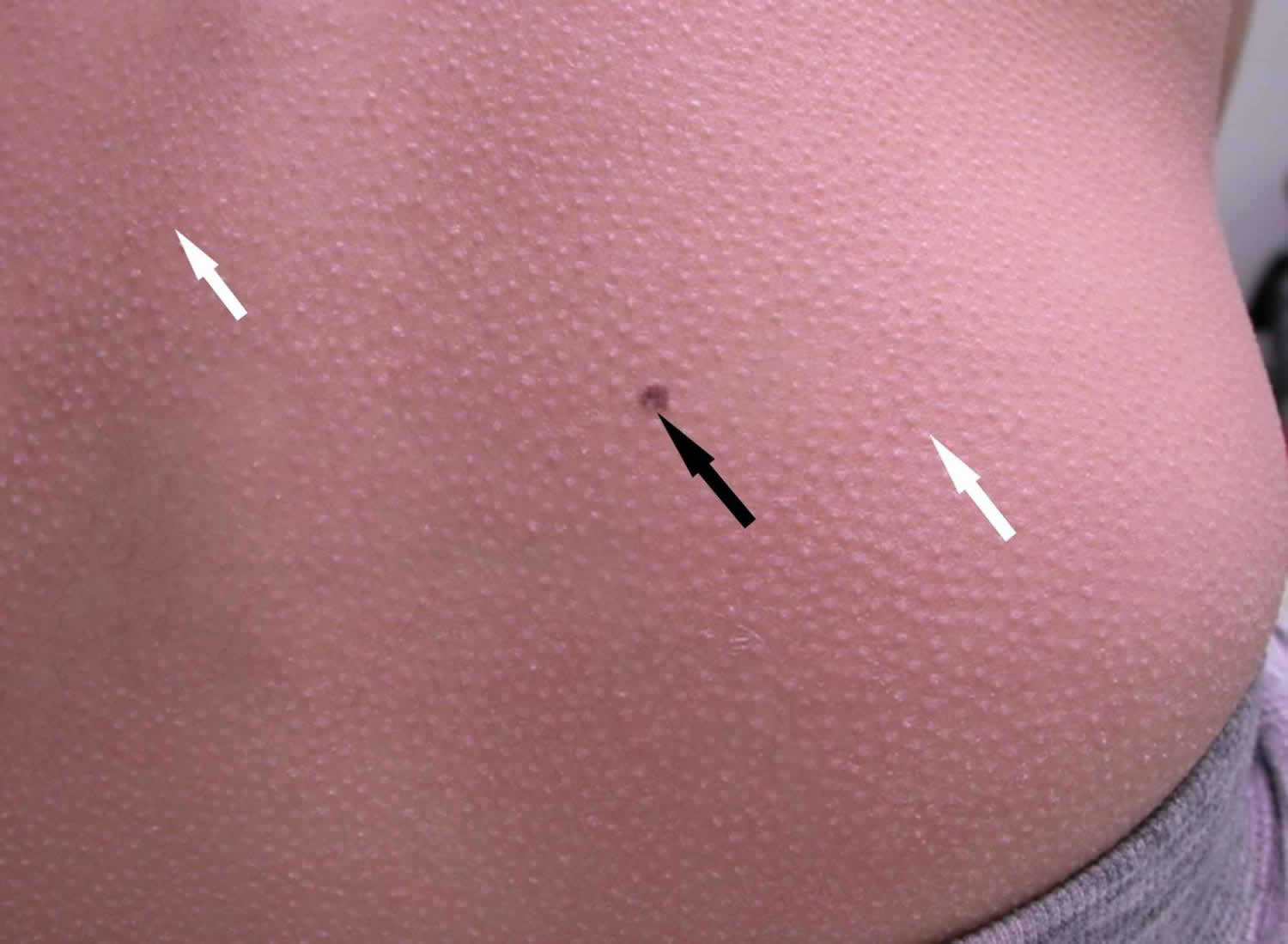

Figure 1. Follicular mucinosis

Footnote: An 11-year-old female with multiple skin papules of 11 months duration. She was on no medications. Past history was only significant for early puberty treated with gonadotropin releasing hormone agonists. Examination revealed widespread follicular papules which were located mainly on the elbows, knees, buttocks, and lower back. Close examination (including evaluation with a dermatoscope) revealed multiple small papular lesions on an erythematous base measuring approximately 0.4 mm. Clinical photograph of the back showing widespread follicular papules (white arrows) and an incidental melanocytic nevus (black arrow).

[Source 1 ]Figure 2. Follicular mucinosis

Footnote: Idiopathic follicular mucinosis with papules on the cheek

Figure 3. Follicular mucinosis as pink patch on the cheek

Figure 4. Mycosis fungoides associated follicular mucinosis on posterior scalp. Note overlying alopecia.

Who is at risk for developing follicular mucinosis?

Due to follicular mucinosis rarity, epidemiologic studies are limited; no predisposing factors have been identified, and no racial or gender predilection has been established. follicular mucinosis may affect children (it is very rare in infants and toddlers), but is most common in the 4th to 6th decades. The epidemiology of follicular mucinosis associated with mycosis fungoides or cutaneous T-cell lymphoma parallels that of mycosis fungoidesor cutaneous T-cell lymphoma and is most common in adults in their 6th decade or older.

Follicular mucinosis has been reported as an incidental finding in a variety of inflammatory skin disorders, such as acne, insect bite reactions, and lichen planus. It has also been rarely reported in patients with neoplastic diseases, most commonly hematologic-based malignancies.

Follicular mucinosis causes

The cause of follicular mucinosis is unknown, but it may have something to do with circulating immune complexes and cell-mediated immunity. What is known is that mucinous material deposits and accumulates in hair follicles and sebaceous glands to create an inflammatory condition that subsequently breaks down the ability of the affected follicles to produce hair.

Controversy exists as to whether follicular mucinosis is a neoplastic process or a reactive process. It may be due to dysfunctional T cells inducing mucin production by fibroblasts surrounding follicular epithelium, or due to excess production of mucin by follicular keratinocytes. Some investigators propose that follicular mucinosis is in fact a form of mycosis fungoides or cutaneous T-cell lymphoma, with a relatively benign or unpredictable course, while others propose that it may be a cutaneous T-cell lymphoid dyscrasia.

Follicular mucinosis differential diagnosis

Secondary causes of follicular mucinosis such as mycosis fungoides may not be diagnosed for some years, necessitating careful follow-up and biopsy. Other conditions that may need to be considered in the differential diagnosis include:

- Alopecia areata, which causes non-scarring localised bald patches

- Seborrheic dermatitis, psoriasis and tinea capitis, which may cause scaly plaques and hair loss

- Discoid lupus erythematosus and lichen planopilaris, which may cause localized areas of scaling and scarring alopecia.

Follicular mucinosis symptoms

Follicular mucinosis lesions are often asymptomatic but may itch or burn; they develop over weeks or months (not days). Follicular mucinosis generally presents as pink-red papules, patches, or plaques most commonly affects face, neck and scalp, but any part of the body may be affected (see Figures 1 to 4). On hair-bearing skin (e.g. scalp), overlying alopecia is notable, hence the term “alopecia mucinosa” (see Figure 4).

Follicular mucinosis signs and symptoms:

- Follicular mucinosis presents as grouped follicular papules within reddened, dry, patches or plaques.

- Patches or plaques are usually 2–5 cm in diameter but can be larger.

- One or more lesions may be present from onset or a single lesion may develop to multiple lesions over a few weeks or months.

- Hair loss is non–scarring and potentially reversible in the early stages, but in more advanced disease the hair follicles are destroyed, causing scarring alopecia.

Primary and acute follicular mucinosis

- Affects people under 40 years.

- Usually, only one or a few lesions arise.

- They are often located on the head, neck and upper arm.

- Most resolve spontaneously within 2 months to 2 years.

Primary and chronic follicular mucinosis

- Affects people over 40 years.

- Widespread and often numerous lesions may persist or recur indefinitely.

- It presents as flat or raised patches that may rarely ulcerate.

- Permanently bald patches are studded with horny plugs.

- Sometimes mucin can be squeezed out of affected follicles.

Secondary follicular mucinosis

- Affects people over 40 years.

- Follicular mucinous degeneration may arise in inflammatory skin diseases such as lupus erythematosus and lichen simplex.

- It may also arise in malignant diseases such as cutaneous T-cell lymphoma (the most common association, affecting 10–30% of cases of follicular mucinosis), Kaposi sarcoma and Hodgkin lymphoma (especially in children).

- Hematopoietic stem cell transplantation 9

- Skin features typical of the underlying disease may also be present.

- A skin biopsy is necessary to distinguish these from primary follicular mucinosis.

Urticaria–like follicular mucinosis

- Presents as itchy small bumps (papules) or raised areas (plaques).

- These are mostly found on the head and neck.

Follicular mucinosis diagnosis

Skin biopsies are required for diagnosis. Follicular mucinosis is diagnosed by its clinical appearance and supported by histopathological findings on biopsy:

- Accumulation of mucin in the pilosebaceous follicle and sebaceous glands (intrafollicular mucin)

- Keratinous debris within a cystic cavity

- Inflammation

- Degeneration of follicular structures.

Histological features of the underlying disease are present in secondary follicular mucinosis.

Histologically, the presence of inflammatory infiltrates confined to the perifollicular or perivascular zones, an absence of atypical cells and minimal to no extension of infiltrates to the epidermis or upper portions of the hair follicle are indicative of a more benign condition. On the other hand, involvement of the upper dermis and epidermis, cytological atypia, and the presence of band-like infiltrates are more commonly seen in association with mycosis fungoides 10. Solitary lesions are also more likely to be benign, though have been reported in follicular mucinosis associated with secondary malignancies 11. There is, however, no clear cut diagnostic criteria to different benign from more malignant disease processes. Studies into various clinical and immunohistochemical methods to achieve this have shown significant overlap in the features of both primary and secondary forms of follicular mucinosis, with none being able to reliably predict disease progression and subsequent outcomes in the affected individuals 12.

Given the association with cutaneous T-cell lymphoma, as well as much rarer associations with other hematologic malignancies (e.g. acute myeloblastic leukemia), a baseline complete blood count (CBC) with differential and lactate dehydrogenase (LDH) level should be obtained, and chest radiograph should be considered.

Follicular mucinosis treatment

There is no proven effective treatment for follicular mucinosis. Therapeutic options and efficacy are based on retrospective case series or anecdotal reports; no controlled trials exist. Usually, primary and acute follicular mucinosis occurring in children resolves spontaneously. Because there is a small chance of spontaneous resolution for other forms of follicular mucinosis, the effect of treatment can be difficult to assess. Some treatments that have been tried with limited success include:

- Topical, intralesional and systemic corticosteroids

- Oral antibiotics such as minocycline

- Dapsone

- Indomethacin

- Interferons

- Topical and systemic photochemotherapy (PUVA)

- Topical nitrogen mustard

- Radiation therapy

- UVA1 phototherapy

- Topical bexarotene 1% gel.

Secondary follicular mucinosis should be treated appropriately for the underlying skin disease, particularly if it is cutaneous T-cell lymphoma.

First line

Solitary or localized lesions

For solitary or localized lesions, topical agents are first line because they are low risk, easy to administer, and low cost. Intralesional corticosteroids or excision should be considered for refractory or localized lesions, where cosmetically acceptable. Photodynamic therapy is an option, but availability is more limited and may be more costly. Suggested therapies are based on anecdotal reports or small case series.

- Topical corticosteroids (mid to high potency)—response expected within 3 months

- Tretinoin 0.01% gel daily—response expected within months

- Pimecrolimus cream twice daily—response expected within 3 months; given the putative association of cutaneous lymphoma with follicular mucinosis, consider warning patients or parents of young patients with follicular mucinosis about the FDA’s black box warning of potential increased risk of lymphoma and skin malignancy with use of pimecrolimus.

- Intralesional corticosteroids—triamcinolone acetonide, 2.5 to 10mg/ml, volume based on lesion size

- Excision

- Photodynamic therapy—topical methylaminolevulinic acid, occluded 3 hours, followed by red light (630nm, 37J/cm², 7.5 minutes); single session per lesion; response expected within 2 months.

Numerous or widespread lesions, unresponsive or intolerant

For more numerous or widespread lesions, or if the patient shows no response or is intolerant to the options above, the following are first-line oral therapeutic options:

Hydroxychloroquine 200mg orally, three times daily for 10 days, followed by 200mg orally, twice daily; response noted within 6 months, begin taper after lesions have cleared. Treatment based on single case series of six patients.

Minocycline 100mg orally, twice daily; response noted within 6 months; begin to taper slowly over months after lesions have cleared. Avoid use in patients under age 8. Treatment based on several case reports.

Second line

The following options have been anecdotally reported to be effective; selection is based on individual patient tolerance and comorbidities, and on the comfort level of the prescribing physician. Consider if patient is intolerant or unresponsive to first-line agents.

- Indomethacin 25mg orally, twice daily; monitor for gastrointestinal adverse effects, electrolytes, and creatinine. Caution if used in patients with gastritis, peptic ulcer disease, or renal insufficiency. Response within 3 months; recurrence may occur upon discontinuation.

- Isotretinoin 0.5mg/kg/day orally; response within 3 months; begin taper over several weeks, after lesions have cleared. In the United States, iPLEDGE enrollment is required for isotretinoin use. Isotretinoin is pregnancy category X. If given to females of childbearing potential, monitor closely for pregnancy. Routine laboratory monitoring is suggested (i.e. chemistries, lipids).

- Dapsone 100mg orally, daily; response within 3 months; taper not defined, recurrence may occur upon discontinuation. Laboratory monitoring required (i.e. CBC, hepatic panel). Contraindicated in patients with glucose-6-phosphate dehydrogenase deficiency.

- Phototherapy using PUVA; caution in patients with history of melanoma and/or aggressive non-melanoma skin cancers or photosensitivity disorders.

Third line

Relative to interventions noted above, these agents are associated with a potentially higher risk or higher cost; or, response and/or dosing are not as well defined.

- Quinacrine 100mg; not available in the United States

- Corticosteroids, oral—dose not delineated in reports

- Methotrexate, oral

- Radiation therapy—skin-directed electron beam or conventional radiation

- Interferon alfa-2a, intralesional 3 million units biweekly X 5, then monthly

Long term management

Discontinue therapy or consider slow titration (over months or years) after complete response is evident. If recurrence is noted upon withdrawal, consider reinstitution of either the same or a new therapy. Of note, follicular mucinosis may resolve spontaneously.

Patients should be advised of the potential relationship with mycosis fungoides or cutaneous T-cell lymphoma, and of the difficulty in distinguishing idiopathic from mycosis fungoides or cutaneous T-cell lymphoma-associated follicular mucinosis with certainty. No data suggest that lack of response to therapy is predictive of higher likelihood of mycosis fungoides or cutaneous T-cell lymphoma association.

Long-term dermatologic follow up is necessary; a reasonable frequency for skin and lymph node exam is every 3-6 months initially, then annually. Periodic laboratory studies (i.e. CBC with differential and LDH) should be performed; frequency should be based on the patient’s symptoms and exam. Baseline blood molecular assay for T cell receptor clonality should be considered if lesional skin is positive for T-cell clonality; baseline blood flow cytometry leukemia/lymphoma profile should also be considered, particularly if the blood molecular is positive for T-cell clonality.

If lesional morphology should change considerably, skin biopsies should be repeated. If highly suspicious clinically and histologically for mycosis fungoides or cutaneous T-cell lymphoma, proper evaluation and staging studies should be performed.

Unusual clinical scenarios to consider in patient management

Serial skin biopsies every 1-2 years to evaluate for mycosis fungoides or cutaneous T-cell lymphoma are warranted for patients whose lesions fail to regress, for patients who develop more widespread lesions despite therapy, and for patients in whom there is a significant change in lesion morphology (e.g. patches progress to thick plaques).

The presence of lesional skin T-cell clonality in follicular mucinosis does not portend a poorer prognosis. Clonal follicular mucinosis may regress completely. Long-term clinical monitoring of patients with follicular mucinosis is suggested.

Controversy exists as to whether follicular mucinosis is in fact a form of mycosis fungoides or cutaneous T-cell lymphoma. Many mycosis fungoides or cutaneous T-cell lymphoma patients with limited disease have an overall good prognosis.

Follicular mucinosis prognosis

The prognosis of follicular mucinosis depends on the specific clinical variant, as follows:

- Primary acute follicular mucinosis usually disappears within 2 years; however, childhood follicular mucinosis is not always self-limited and may possibly be related to Hodgkin disease.

- Primary chronic follicular mucinosis usually lingers for several years, but it can fluctuate in the extent of skin involvement at any given time.

- Secondary follicular mucinosis has the least favorable prognosis when associated with coexistent malignancy.

Mortality is related to the coexistence of mycosis fungoides in secondary follicular mucinosis. An estimated 15-40% of adults with follicular mucinosis will eventually develop lymphoma, if they do not already have it. The malignant potential of follicular mucinosis cannot be fully assessed because of the enigmatic nature of this and other cutaneous T-cell abnormalities. The morbidity of primary follicular mucinosis is generally restricted to cosmesis; whereas, in cases of secondary follicular mucinosis, morbidity is related to the associated disease process.

References- Akinsanya A O, Tschen J A (May 24, 2019) Follicular Mucinosis: A Case Report. Cureus 11(5): e4746. doi:10.7759/cureus.4746

- Pinkus H: Alopecia mucinosa. Inflammatory plaques with alopecia characterized by root-sheath mucinosis. Arch Dermatol. 1983, 119:690-697. 10.1001/archderm.1983.01650320064019

- Kim R, Winkelmann RK: Follicular mucinosis (alopecia mucinosa). Arch Dermatol. 1962, 85:490-498. 10.1001/archderm.1962.01590040054007

- Passos PCVR, Zuchi MF, Fabre AB, Martins LEAM: Follicular mucinosis – case report. An Bras Dermatol. 2013, 88:337-339. 10.1590/abd1806-4841.20142968

- Fonseca A de PM da, Bona SH, Fonseca WSM da, Campelo FS, Rego PM de M: Follicular mucinosis: literature review and case report. An Bras Dermatol. 2002, 77:701-706. 10.1590/S0365-05962002000600007

- Lancer HA, Bronstein BR, Nakagawa H, Bhan AK, Mihm MC Jr: Follicular mucinosis: a detailed morphologic and inmmunophatologic study. J Am Acad Dermatol. 1984, 10:760-768. 10.1016/S0190-9622(84)70091-0

- Clark-Loeser L, Latkowski J-A: Follicular mucinosis associated with mycosis fungoides. Dermatol Online J. 2004, 56:1882.

- Zvulunov A, Shkalim V, Ben-Amitai D, Feinmesser M: Clinical and histopathologic spectrum of alopecia mucinosa/follicular mucinosis and its natural history in children. J Am Acad Dermatol. 2012, 67:1174-1181. 10.1016/j.jaad.2012.04.015

- Mir-Bonafé JM, Cañueto J, Fernández-López E, Santos-Briz A. Follicular mucinosis associated with nonlymphoid skin conditions. Am J Dermatopathol. 2014 Sep;36(9):705-9. doi: 10.1097/01.dad.0000451564.29918.31

- Gibson LE, Muller SA, Leiferman KM, Peters MS: Follicular mucinosis: clinical and histopathologic study. J Am Acad Dermatol. 1989, 20:441-446. 10.1016/S0190-9622(89)70055-4

- Cerroni L, Fink-Puches R, Bäck B, Kerl H: Follicular mucinosis: a critical reappraisal of clinicopathologic features and association with mycosis fungoides and Sézary syndrome. Arch Dermatol. 2002, 138:182-189. 10.1001/archderm.138.2.182

- Rongioletti F, Lucchi SD, Meyes D, et al.: Follicular mucinosis: a clinicopathologic, histochemical, immunohistochemical and molecular study comparing the primary benign form and the mycosis fungoides-associated follicular mucinosis. J Cutan Pathol. 2010, 37:15-19. 10.1111/j.1600-0560.2009.01338.x