GM1 gangliosidosis

GM1 gangliosidosis is a rare inherited lysosomal storage disorder that progressively destroys nerve cells (neurons) in the brain and spinal cord 1. Some researchers classify GM1 gangliosidosis into three major types based on the age at which signs and symptoms first appear: classic infantile (GM1 gangliosidosis type 1); juvenile (GM1 gangliosidosis type 2); and adult onset or chronic (GM1 gangliosidosis type 3). Although the three types differ in severity, their features can overlap significantly. Because of this overlap, other researchers believe that GM1 gangliosidosis represents a continuous disease spectrum instead of three distinct types.

GM1 gangliosidosis is estimated to occur in 1 in 100,000 to 200,000 newborns. GM1 gangliosidosis is caused by mutations in the GLB1 gene and is inherited in an autosomal recessive manner. Treatment is currently symptomatic and supportive.

The signs and symptoms of the most severe form of GM1 gangliosidosis is called GM1 gangliosidosis type 1 or the infantile GM1 gangliosidosis, usually become apparent by the age of 6 months. GM1 gangliosidosis type 1 is reported more frequently than the other forms of this condition. Infants with GM1 gangliosidosis type 1 of the disorder typically appear normal until their development slows and muscles used for movement weaken. Affected infants eventually lose the skills they had previously acquired (developmentally regress) and may develop an exaggerated startle reaction to loud noises. As the disease progresses, children with GM1 gangliosidosis type 1 develop an enlarged liver and spleen (hepatosplenomegaly), skeletal abnormalities, seizures, profound intellectual disability, and clouding of the clear outer covering of the eye (the cornea). Loss of vision occurs as the light-sensing tissue at the back of the eye (the retina) gradually deteriorates. An eye abnormality called a cherry-red spot, which can be identified with an eye examination, is characteristic of this disorder. In some cases, affected individuals have distinctive facial features that are described as “coarse,” enlarged gums (gingival hypertrophy), and an enlarged and weakened heart muscle (cardiomyopathy). Individuals with GM1 gangliosidosis type 1 usually do not survive past early childhood.

GM1 gangliosidosis type 2 consists of intermediate forms of the condition, also known as the late infantile and juvenile forms. Children with GM1 gangliosidosis type II have normal early development, but they begin to develop signs and symptoms of the condition around the age of 18 months (late infantile form) or 5 years (juvenile form). Individuals with GM1 gangliosidosis type II experience developmental regression but usually do not have cherry-red spots, distinctive facial features, or enlarged organs. Type II usually progresses more slowly than type I, but still causes a shortened life expectancy. People with the late infantile form typically survive into mid-childhood, while those with the juvenile form may live into early adulthood.

GM1 gangliosidosis type 3 is known as the adult or chronic form, and it represents the mildest end of the disease spectrum. Most individuals with GM1 gangliosidosis type 3 are of Japanese descent. The age at which symptoms first appear varies in GM1 gangliosidosis type 3, although most affected individuals develop signs and symptoms in their teens. The characteristic features of GM1 gangliosidosis type 3 include involuntary tensing of various muscles (dystonia) and abnormalities of the spinal bones (vertebrae). Life expectancy varies among people with GM1 gangliosidosis type 3.

There is no treatment or cure for GM1 gangliosidosis disease but there are ways to manage symptoms. These range from life-extending interventions like a feeding tube to comfort measures like massage to promote relaxation. Anticonvulsants may initially control seizures. Other supportive treatment includes proper nutrition and hydration, and keeping the airway open. Restricting your diet does not prevent lipid buildup in cells and tissues.

GM1 gangliosidosis type 1

GM1 gangliosidosis type 1 also known as classic infantile GM1 gangliosidosis, is the most severe type, with onset shortly after birth (usually within 6 months of age). Affected infants typically appear normal until onset, but developmental regression (loss of acquired milestones) eventually occurs. Signs and symptoms may include neurodegeneration, seizures, liver and spleen enlargement, coarsening of facial features, skeletal irregularities, joint stiffness, a distended abdomen, muscle weakness, an exaggerated startle response to sound, and problems with gait (manner of walking). About half of people with this type develop cherry-red spots in the eye. Children may become deaf and blind by one year of age 2. Affected children typically do not live past 2 years of age. Respiratory health and seizure management are the two main symptom management challenges in Infantile GM1 gangliosidosis type 1.

GM1 gangliosidosis type 1 symptoms

Symptoms appear within the first 6 months of age and may be apparent at birth. Early symptoms include poor appetite, weak suck and failure to thrive. Only about 50% of cases display the cherry-red spot in the back of the eye.

First signs – A baby with Classic Infantile GM1 gangliosidosis displays symptoms within the first 6 months. Symptoms may be apparent at birth. Early symptoms include poor appetite, weak suck and failure to thrive. Only about 50% of cases display the cherry-red spot in the back of the eye.

Gradual Loss of skills – Infantile GM1 gangliosidosis children never learn to sit up or crawl, have generalized poor muscle strength, demonstrate progressive inability to swallow and have difficulty breathing. Some children also have an enlarged heart, cardiomegaly.

By Age 2 and beyond – Most children experience recurrent seizures by age 1 and eventually lose muscle function, and mental function and sight, becoming mostly non-responsive to their environment.

GM1 gangliosidosis type 1 diagnosis

Babies affected by the Infantile form of GM1 gangliosidosis type 1 are frequently diagnosed by the cherry-red spot on the retina of the eye. Initially many parents notice developmental delays but pediatricians often dismiss these concerns by stating “every baby develops differently” and “the baby will catch up”. Often at about 10-14 months of age, children may start to exhibit trouble tracking and/or focusing with their eyes, so parents schedule an appointment for an eye exam. The cherry-red spot is quickly seen and an initial diagnosis of Tay-Sachs or similar devastating disease is made.

Children affected by Juvenile form of GM1 gangliosidosis type 1 do not exhibit the tell-tale cherry-red spot in the eye. This can make the road to diagnosis long and challenging. Unfortunately many healthcare providers are not aware of the rare juvenile forms of these diseases and dismiss the initial diagnosis due to the age of the child.

Late Onset GM1 gangliosidosis type 1 may be hard to diagnosis. Some adults go 5 or more years before learning their true diagnosis. It may sometimes be misdiagnosed as Multiple Sclerosis or amyotrophic lateral sclerosis (ALS).

Adults affected by the adult form of GM1 gangliosidosis disease do not exhibit the tell-tale cherry-red spot. This can make the road to diagnosis long and challenging. Unfortunately many healthcare providers are not aware of the rare adult forms of these diseases and dismiss the initial diagnosis due to the age of the patient.

Adults that display mental health symptoms before physical symptoms often experience the longest road to diagnosis.

Diagnosis can also be made by a neurologist or geneticists and the completion of a metabolic evaluation.

GM1 gangliosidosis is diagnosed through a blood test to check the level of beta-galactosidase (GLB1). A follow-up DNA test may be recommended. Any doctor can order the GM1 gangliosidosis GLB1 blood test. Often, diagnosis is made by a neurologist or geneticist.

GM1 gangliosidosis type 2

Symptoms appear after the first year of life, typically between ages 2 and 5, but can occur anytime during childhood. Early symptoms of GM1 include lack of coordination or clumsiness and muscle weakness such as struggling with stairs. A child may also exhibit slurred speech, swallowing difficulties and muscle cramps.

Progressive loss of ambulatory skills followed by respiratory health and seizure management are the main symptom management issues in Juvenile GM1 gangliosidosis type 2.

First signs – Early symptoms of GM1 gangliosidosis include lack of coordination or clumsiness and muscle weakness such as struggling with stairs. A child may also exhibit slurred speech, swallowing difficulties and muscle cramps.

Gradual Loss of skills – Over time children with GM1 gangliosidosis slowly decline, losing their ability to walk, eat on their own and communicate. Children are prone to respiratory infections and often experience recurrent bouts of pneumonia. Many have seizures.

Range of severity – Juvenile GM1 gangliosidosis has a broad range of severity. In most cases, the earlier the first signs are observed, the more quickly the disease will progress. For example, a child with first symptoms at age 2 will decline faster than a child with first symptoms at age 5.

GM1 gangliosidosis type 3

Symptoms typically appear in adolescence or early adulthood, but sometimes later. Early symptoms of Late Onset GM1 gangliosidosis type 3 include clumsiness and muscle weakness in the legs. Once diagnosed, adults often reflect back to their childhood and may notice experiencing symptoms much earlier such as not being athletic and/or speech difficulties or a stutter as a child or teenager.

First signs – Early symptoms of Late Onset GM1 gangliosidosis include clumsiness and muscle weakness in the legs. Once diagnosed, adults often reflect back to their childhood and may notice experiencing symptoms much earlier such as not being athletic and/or speech difficulties or a stutter as a child or teenager.

Gradual Loss of skills – Over time, adults with Late Onset GM1 gangliosidosis slowly decline. Adults frequently require more mobility assistance, i.e. cane to walker to wheelchair. Many experience speech and swallowing difficulties but few require a feeding tube.

Late Onset GM1 gangliosidosis type 3 is a challenging and debilitating disorder but doesn’t always shorten life span like the childhood forms of GM1 gangliosidosis.

GM1 gangliosidosis causes

Mutations in the GLB1 gene cause GM1 gangliosidosis. The GLB1 gene provides instructions for making an enzyme called beta-galactosidase (β-galactosidase), which plays a critical role in the brain. This enzyme is located in lysosomes, which are compartments within cells that break down and recycle different types of molecules. Within lysosomes, β-galactosidase helps break down several molecules, including a substance called GM1 ganglioside. GM1 ganglioside is important for normal functioning of nerve cells in the brain.

Mutations in the GLB1 gene reduce or eliminate the activity of β-galactosidase. Without enough functional β-galactosidase, GM1 ganglioside cannot be broken down when it is no longer needed. As a result, this substance accumulates to toxic levels in many tissues and organs, particularly in the brain. Progressive damage caused by the buildup of GM1 ganglioside leads to the destruction of nerve cells in the brain, causing many of the signs and symptoms of GM1 gangliosidosis. In general, the severity of GM1 gangliosidosis is related to the level of β-galactosidase activity. Individuals with higher enzyme activity levels usually have milder signs and symptoms than those with lower activity levels because they have less accumulation of GM1 ganglioside within the body.

Conditions such as GM1 gangliosidosis that cause molecules to build up inside the lysosomes are called lysosomal storage disorders.

GM1 gangliosidosis inheritance pattern

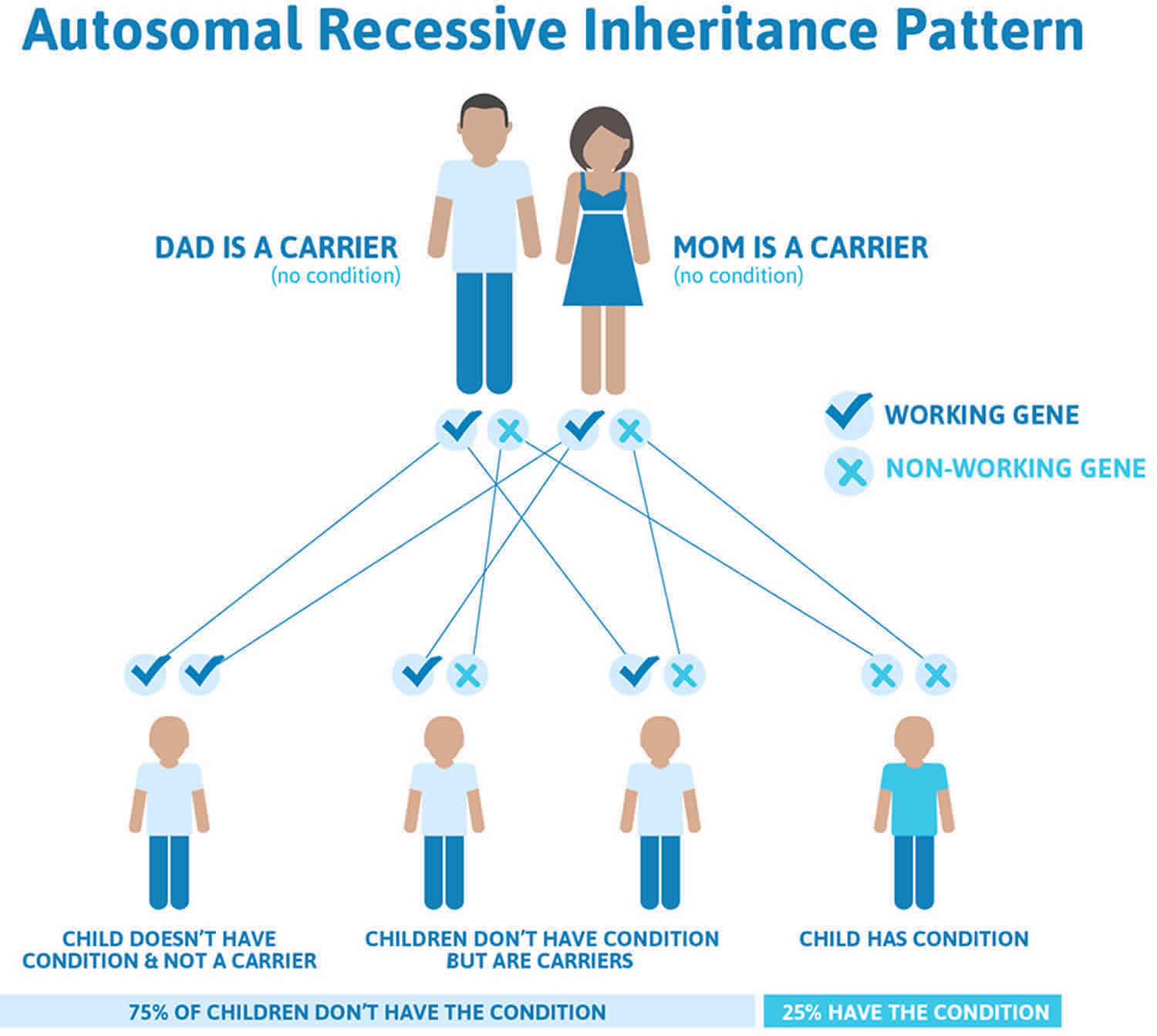

GM1 gangliosidosis is inherited in an autosomal recessive pattern, which means both copies of the gene in each cell have mutations. The parents of an individual with an autosomal recessive condition each carry one copy of the mutated gene, but they typically do not show signs and symptoms of the condition.

It is rare to see any history of autosomal recessive conditions within a family because if someone is a carrier for one of these conditions, they would have to have a child with someone who is also a carrier for the same condition. Autosomal recessive conditions are individually pretty rare, so the chance that you and your partner are carriers for the same recessive genetic condition are likely low. Even if both partners are a carrier for the same condition, there is only a 25% chance that they will both pass down the non-working copy of the gene to the baby, thus causing a genetic condition. This chance is the same with each pregnancy, no matter how many children they have with or without the condition.

- If both partners are carriers of the same abnormal gene, they may pass on either their normal gene or their abnormal gene to their child. This occurs randomly.

- Each child of parents who both carry the same abnormal gene therefore has a 25% (1 in 4) chance of inheriting a abnormal gene from both parents and being affected by the condition.

- This also means that there is a 75% ( 3 in 4) chance that a child will not be affected by the condition. This chance remains the same in every pregnancy and is the same for boys or girls.

- There is also a 50% (2 in 4) chance that the child will inherit just one copy of the abnormal gene from a parent. If this happens, then they will be healthy carriers like their parents.

- Lastly, there is a 25% (1 in 4) chance that the child will inherit both normal copies of the gene. In this case the child will not have the condition, and will not be a carrier.

These possible outcomes occur randomly. The chance remains the same in every pregnancy and is the same for boys and girls.

Figure 1 illustrates autosomal recessive inheritance. The example below shows what happens when both dad and mum is a carrier of the abnormal gene, there is only a 25% chance that they will both pass down the abnormal gene to the baby, thus causing a genetic condition.

Figure 1. GM1 gangliosidosis autosomal recessive inheritance pattern

People with specific questions about genetic risks or genetic testing for themselves or family members should speak with a genetics professional.

Resources for locating a genetics professional in your community are available online:

- The National Society of Genetic Counselors (https://www.findageneticcounselor.com/) offers a searchable directory of genetic counselors in the United States and Canada. You can search by location, name, area of practice/specialization, and/or ZIP Code.

- The American Board of Genetic Counseling (https://www.abgc.net/about-genetic-counseling/find-a-certified-counselor/) provides a searchable directory of certified genetic counselors worldwide. You can search by practice area, name, organization, or location.

- The Canadian Association of Genetic Counselors (https://www.cagc-accg.ca/index.php?page=225) has a searchable directory of genetic counselors in Canada. You can search by name, distance from an address, province, or services.

- The American College of Medical Genetics and Genomics (http://www.acmg.net/ACMG/Genetic_Services_Directory_Search.aspx) has a searchable database of medical genetics clinic services in the United States.

GM1 gangliosidosis symptoms

Infantile GM1 gangliosidosis

In the most common infantile GM1 gangliosidosis, coarse facial features, hepatosplenomegaly, generalized skeletal dysplasia (dysostosis multiplex), macular cherry-red spots, and developmental delay/arrest (followed by progressive neurologic deterioration) usually occur within the first 6 months of life. Nonimmune hydrops has been reported. An increased incidence of Mongolian spots has also been reported. A wide spectrum of variability is observed in the appearance and progression of the typical dysmorphic features. As many as 50% of affected infants have a macular cherry-red spot 3.

Juvenile GM1 gangliosidosis

The juvenile GM1 gangliosidosis is characterized by a later age of onset, less hepatosplenomegaly (if any), fewer cherry-red spots (if any), dysmorphic features, or skeletal changes (vertebral dysplasia may be detected radiographically) 4.

Adult GM1 gangliosidosis

The adult GM1 gangliosidosis is characterized by normal early neurologic development, with variable age of clinical presentation. Slowly progressing dementia with parkinsonian features and extrapyramidal disease is common. Intellectual impairment may be initially absent or mild but progresses with time. Generalized dystonia with speech and gait disturbance is the most frequently reported early feature. Typically, no hepatosplenomegaly, cherry-red spots, dysmorphic features, or skeletal changes are present aside from scoliosis (mild vertebral changes may be revealed with radiography), but short stature is common 5.

Neurologic findings

- Developmental delay, arrest, and regression

- Generalized hypotonia initially, developing into spasticity

- Exaggerated startle response

- Hyperreflexia

- Seizures

- Extrapyramidal disease (adult subtype)

- Generalized dystonia (adult subtype) 5

- Ataxia (adult subtype)

- Dementia (adult subtype)

- Speech and swallowing disturbance (adult subtype) 6

Ophthalmologic findings

- Macular cherry-red spots

- Present in as many as 50% of affected infants

- May be found in other genetic disorders (eg, mucolipidosis type I, Niemann-Pick disease, Krabbe disease, Tay-Sachs disease)

- Optic atrophy

- Corneal clouding

Dysmorphic features

- Frontal bossing

- Depressed nasal bridge and broad nasal tip

- Large low-set ears

- Long philtrum

- Gingival hypertrophy and macroglossia 7

Coarse skin

Hirsutism

Cardiovascular – Dilated and/or hypertrophic cardiomyopathy, valvulopathy

Abdomen

- Hepatosplenomegaly

- Inguinal hernia

Skeletal abnormalities

- Lumbar gibbus deformity and kyphoscoliosis

- Dysostosis multiplex

- Broad hands and feet

- Brachydactyly

- Joint contractures

Angiokeratoma corporis diffusum (reported infrequently)

Hydrops fetalis (has been reported)

Prominent dermal melanocytosis (Mongolian spots) 8.

GM1 gangliosidosis complications

Patients with GM1 gangliosidosis are at risk for aspiration pneumonia and recurrent respiratory infections resulting from neurologic compromise.

Congestive heart failure may result secondary to cardiomyopathy.

Atlantoaxial instability can develop because of abnormally shaped cervical vertebrae. If this occurs, patients should be monitored, and they eventually should undergo surgical stabilization to avoid the risk of spinal cord injury.

GM1 gangliosidosis diagnosis

GM1 gangliosidosis is diagnosed through a blood test to check the level of beta-galactosidase (GLB1) enzyme. A follow-up DNA testing of the GLB1 gene may be recommended. Despite the availability of molecular genetic testing, the mainstay of diagnosis will likely continue to be enzyme activity because of cost and difficulty in interpreting unclear results 9. However, enzyme activity may not be predictive of carrier status in relatives of affected people. Carrier testing for at-risk family members is done with molecular genetic testing, and is possible if the disease-causing mutations in the family are already known 9.

Any doctor can order the GM1 gangliosidosis GLB1 blood test. Often, diagnosis is made by a neurologist or geneticist.

GM1 gangliosidosis treatment

There is currently no effective medical treatment for GM1 gangliosidosis 10. Symptomatic treatment for some of the neurologic signs and symptoms is available, but does not significantly alter the progression of the condition 10. For example, anticonvulsants may initially control seizures. Supportive treatments may include proper nutrition and hydration, and keeping the affected individual’s airway open 11.

Bone marrow transplantation was reportedly successful in an individual with infantile/juvenile GM1 gangliosidosis; however, no long-term benefit was reported. Presymptomatic cord-blood hematopoietic stem-cell transplantation has been advocated by some as a possible treatment due to its success in other lysosomal storage disorders 10.

Neurologic and orthopedic complications may prevent adequate physical activity, but affected individuals may benefit from physical and occupational therapy 10.

Active research in the areas of enzyme replacement and gene therapy for GM1 gangliosidosis is ongoing but has not yet advanced to human trials 12. In cats, AAV gene therapy has shown significant therapeutic benefit, resulting in near-normal function up to 5 years posttreatment 13.

Researchers at the University of Minnesota are conducting a 5-year longitudinal phase 4 study using a combination of miglustat and the ketogenic diet for infantile and juvenile GM1 gangliosidosis 14. An Italian study published in June 2017 used miglustat as treatment in three patients with GM1 gangliosidosis (2 juvenile, 1 adult) and showed a reduction of disease progression and, in some measures, reversal of symptoms 15.

GM1 gangliosidosis prognosis

The long-term outlook or prognosis for people with GM1 gangliosidosis depends on the type, age of onset, and severity of the condition in each person.

- GM1 gangliosidosis type 1 or Infantile GM1 gangliosidosis: Death usually occurs during the second year of life because of infection and cardiopulmonary failure 7.

- GM1 gangliosidosis type 2 or Juvenile GM1 gangliosidosis: Death usually occurs before the second decade of life 7.

- GM1 gangliosidosis type 3 or Adult GM1 gangliosidosis: Phenotypic variability is marked, but progressive development of neurologic sequelae usually leads to a shortened lifespan 7.

GM1 gangliosidosis type 1, also known as the infantile GM1 gangliosidosis, is the most severe type of GM1 gangliosidosis . Children with GM1 gangliosidosis type 1 usually do not survive past early childhood due to infection and cardiopulmonary failure. GM1 gangliosidosis type 2, which includes the late-infantile and juvenile forms, is an intermediate form of the condition. People with GM1 gangliosidosis type 2 who have late-infantile onset usually survive into mid-childhood, while those with juvenile onset may live into early adulthood. GM1 gangliosidosis type 3, known as the adult or chronic form of GM1 gangliosidosis, is the mildest form of the condition. The age of onset and life expectancy for people with GM1 gangliosidosis type 3 varies, but life expectancy is usually shortened 10.

References- GM1 gangliosidosis. https://rarediseases.info.nih.gov/diseases/10891/gm1-gangliosidosis

- GM1 Gangliosidosis-1. https://www.ntsad.org/index.php/the-diseases/gm-1

- Dweikat I, Libdeh BA, Murrar H, Khalil S, Maraqa N. Gm1 gangliosidosis associated with neonatal-onset of diffuse ecchymoses and mongolian spots. Indian J Dermatol. 2011 Jan. 56(1):98-100.

- Takenouchi T, Kosaki R, Nakabayashi K, Hata K, Takahashi T, Kosaki K. Paramagnetic Signals in the Globus Pallidus as Late Radiographic Sign of Juvenile-Onset GM1 Gangliosidosis. Pediatr Neurol. 2014 Oct 16.

- Roze E, Paschke E, Lopez N, et al. Dystonia and parkinsonism in GM1 type 3 gangliosidosis. Mov Disord. 2005 Oct. 20(10):1366-9.

- Muthane U, Chickabasaviah Y, Kaneski C, et al. Clinical features of adult GM1 gangliosidosis: report of three Indian patients and review of 40 cases. Mov Disord. 2004 Nov. 19(11):1334-41.

- Suzuki Y, Oshima A, Nanba E. B-Galactosidase deficiency (B-Galactosidosis): GM1 gangliosidosis and Morquio B disease. Scriver CR, Sly WS, Valle D, et al, eds. The Metabolic and Molecular Bases of Inherited Disease. 8th ed. McGraw-Hill Professional; 2001. 3775-810.

- Armstrong-Javors A, Chu CJ. Child Neurology: Exaggerated dermal melanocytosis in a hypotonic infant: A harbinger of GM1 gangliosidosis. Neurology. 2014 Oct 21. 83(17):e166-8.

- Regier DS, Tifft CJ. GLB1-Related Disorders. 2013 Oct 17 [Updated 2019 Aug 29]. In: Adam MP, Ardinger HH, Pagon RA, et al., editors. GeneReviews® [Internet]. Seattle (WA): University of Washington, Seattle; 1993-2019. Available from: https://www.ncbi.nlm.nih.gov/books/NBK164500

- GM1 Gangliosidosis. https://emedicine.medscape.com/article/951637-overview

- Generalized Gangliosidoses Information Page. https://www.ninds.nih.gov/Disorders/All-Disorders/Generalized-Gangliosidoses-Information-Page

- Brunetti-Pierri N, Scaglia F. GM1 gangliosidosis: review of clinical, molecular, and therapeutic aspects. Mol Genet Metab. 2008 Aug. 94(4):391-6.

- Gray-Edwards HL, Regier DS, Shirley JL, Randle AN, et al. Novel Biomarkers of Human GM1 Gangliosidosis Reflect the Clinical Efficacy of Gene Therapy in a Feline Model. Mol Ther. 2017 Apr 5. 25 (4):892-903.

- Synergistic Enteral Regimen for Treatment of the Gangliosidoses (Syner-G). https://clinicaltrials.gov/ct2/show/NCT02030015?cond=NCT02030015&rank=1

- Deodato, F., Procopio, E., Rampazzo, A. et al. The treatment of juvenile/adult GM1-gangliosidosis with Miglustat may reverse disease progression. Metab Brain Dis. 2017 June 3. 32:1529-1536.