Grisel syndrome

Grisel syndrome is a rare but dangerous cause of torticollis (wry neck) in which the neck muscles contract, causing the head to twist to one side, that involves partial dislocation (subluxation) of atlanto-axial joint (C1–C2 vertebrae) from inflammatory ligamentous laxity following an infectious process in the head and neck, usually a retropharyngeal abscess following upper airway infections and otorhinolaryngology procedures 1. Grisel syndrome is the consequence of the relative weakness of ligaments and joint capsules, horizontal joint articulation, and small supporting muscles 2. Congenital conditions that involve ligamentous laxity such as Down and Marfan syndromes present a higher risk of atlantoaxial subluxation 3. Grisel syndrome usually more commonly in infants or young children and only rare cases involving adults have been reported 4 and usually presents with cervical pain and torticollis, in addition to symptoms of the primary infection. Variable presentation may be associated with fever, difficulty swallowing (dysphagia) and hearing loss. Neurological complications ranging from radiculopathy to death from medullary compression occur in 15% of the cases 5.

The recognition of the Grisel’s syndrome is based on clinical and neuroradiological investigations, and early diagnosis and specific treatment are crucial to the successful outcome of the disease.

In early stages medical treatment with antibiotics is adequate. With late presentation, invasive surgical treatment may be necessary to prevent morbidity. Therefore early recognition of this rare condition is vital to prevent long-term complications with possible neurological deficit 6.

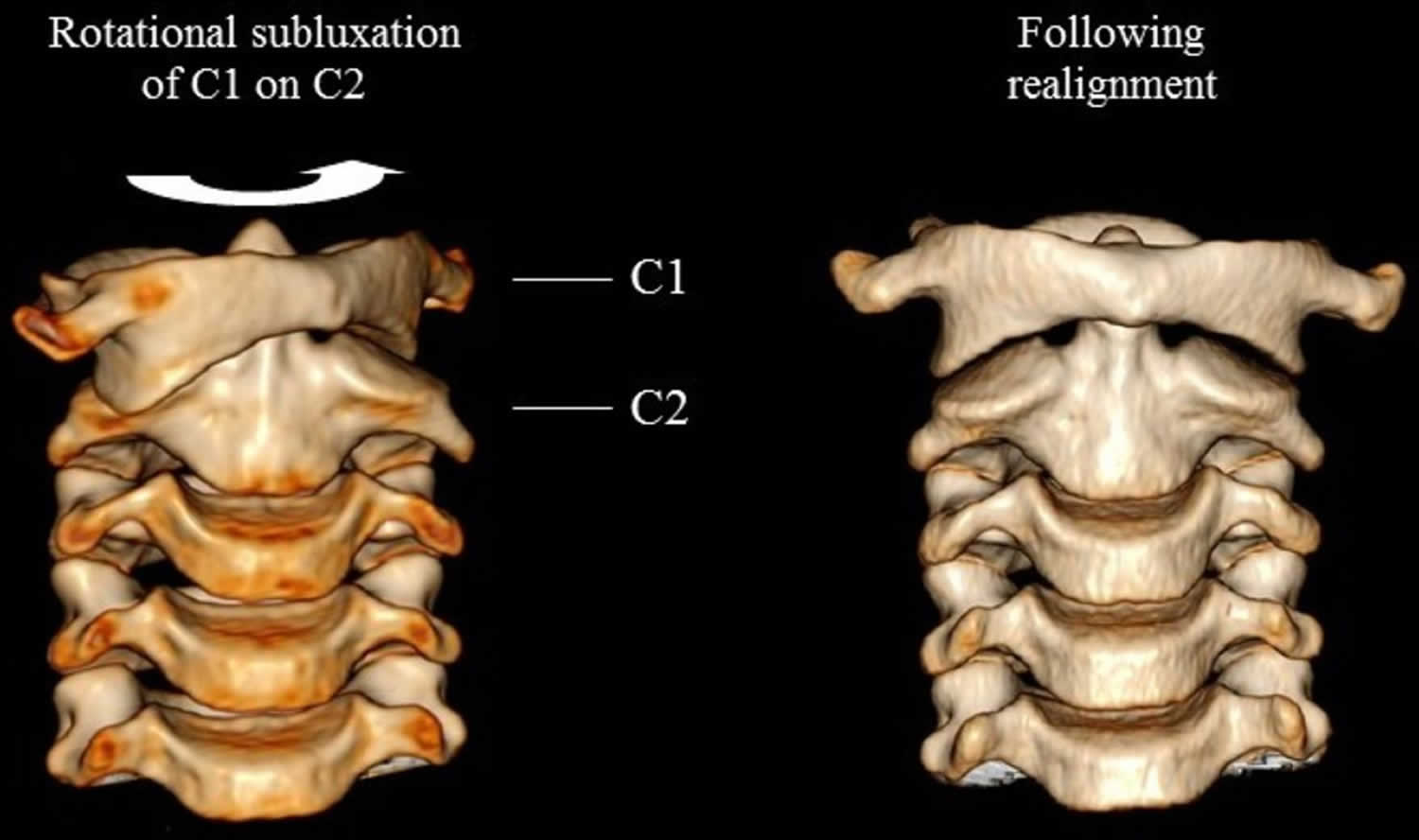

Figure 1. Grisel syndrome

Footnote: A 7-year-old girl developed severe neck stiffness and trismus (lockjaw or reduced opening of the jaws) while on treatment for a presumed throat infection. Examination findings included a fixed torticollis with restricted neck movements in all directions; erythematous tonsils and cervical lymphadenopathy. Group A strep was cultured from her throat swab. She coincidentally had diabetes mellitus. CT neck with contrast revealed subluxation of C1/C2 (Figure 2, left); and bilateral retropharyngeal abscess.

[Source 7 ]Figure 2. Grisel syndrome cervical spine

Figure 3. Grisel syndrome

Footnote: A 9-year-old boy with Grisel syndrome. Typical cock robin posture.

[Source 8 ]Grisel syndrome causes

Grisel syndrome may result from any inflammatory process of the head and neck. Upper respiratory tract infections are the commonest cause of Grisel syndrome. However, any inflammatory process of the head and neck including post-surgical inflammation (for example, adenotonsillectomy), can result in Grisel syndrome.

The most common causes of Grisel syndrome are as follows 1:

- upper respiratory tract infections

- tonsillectomy/adenotonsillectomy

- otitis media

- other ear, nose and throat (ENT) infections/surgery

The causative organisms are usually 9:

- Staphylococcus aureus

- Group B Streptococcus (Streptococcus pyogenes)

- oral flora

- Epstein-Barr virus,

- Kawasaki disease 10,

- Mycoplasma pneumoniae.

The main causes of Grisel’s syndrome were infection (48%) and post-adenotonsillectomy (31%). Less common causes included other postoperative cases such as pharyngoplasty and ear operations 11.

Predisposing factors are trauma, hyperlaxity of the transverse and alar ligaments of the atlantoaxial joints 12.

Grisel syndrome symptoms

Grisel syndrome has a variable presentation, time between inciting event and symptom onset is variable, and laboratory investigations may be normal. So diagnosis is difficult. However, typically presentation consists of 9:

- torticollis

- reduced neck mobility

- cervical pain (neck pain)

- symptoms related to underlying infection.

Upon physical examination, three signs define the clinical diagnosis of atlanto-axial rotatory subluxation 13:

- palpable deviation of the spinous process of the axis in the same direction of head rotation,

- spasm of the sternocleidomastoid muscle ipsilateral to the rotation 2

- inability to turn the head beyond the midline in the direction of the side opposite to the lesion 14.

Nuchal pain increases when an attempt is made to perform active contralateral neck rotation. Thus, the patient keeps his or her head motionless, in subtle rotation and flexion, with the chin in a position opposite to that of the affected side, characterizing the pathologic posture denoted “cock robin posture,” a term coined in reference to the posture of a robin with its head in rotation (Figure 3) 15. The reported case showed complete contralateral cervical rotation not typical of cock robin posture. However, the absence of spasm of the sternocleidomastoid muscle contralateral to the rotation might alert that this posture may not correspond to a torticollis elicited by muscle spasm.

Neurological complications can range from radiculopathy to death from medullary compression 1.

The diagnosis of the syndrome should be prompt. Diagnosis after 3 weeks is related to failure of conservative treatment, including closed reduction, greater risks of recurrence and permanent craniofacial and/or cervical deformities, and the need for surgical treatment 16. These might occur because of chronic changes in the transverse and alar ligaments 2.

Grisel syndrome diagnosis

Plain radiographs are of limited value in establishing a diagnosis. Best investigation is three-dimensional computed tomography (CT) of the craniocervical transition, which demonstrate abnormal lateral placement of C1 on C2, and of occipital facets on C1. The CT scan must be performed with the head in neutral position to avoid misdiagnosis. The three-dimensional reconstruction of CT permits a clear visualization of C1–C2 rotation, including the loss of congruence of the articular facets. The axial images permit the measurement of atlantodental interval (ADI), which is the horizontal distance between the anterior arch of the atlas and the dens of the axis, used in the diagnosis of atlanto-occipital dissociation injuries and injuries of the atlas and axis. The normal measurement is 2 to 3 mm in adults and up to 5 mm in children 17. An increase in this distance is an indirect result of injury to the transverse ligament, which is related to greater instability of the lesion, with the possible need for surgical treatment. MRI may be useful in evaluating inflammatory changes in the surrounding soft tissues.

Diagnostic findings of Grisel syndrome 8:

- History of upper airway infections and/or head and neck surgeries

- Complaint of torticollis a few days after onset of infection/surgery

- Anomalous rotation and mild flexion of the head, with the chin turned toward the contralateral side

- Pain with active or passive head rotation

- Elevation of C reactive protein and of leukocytes during the first days of torticollis, with later normalization of these parameters, usually without a fever

- Anteroposterior radiograph may show enlargement of the C1 lateral mass that is dislocated forward (contralateral to neck rotation)

- Lateral radiograph of the cervical spine may show an atlantodental interval larger than 5 mm in severe cases

- Computed tomography (CT) showing rotatory subluxation of C1–C2.

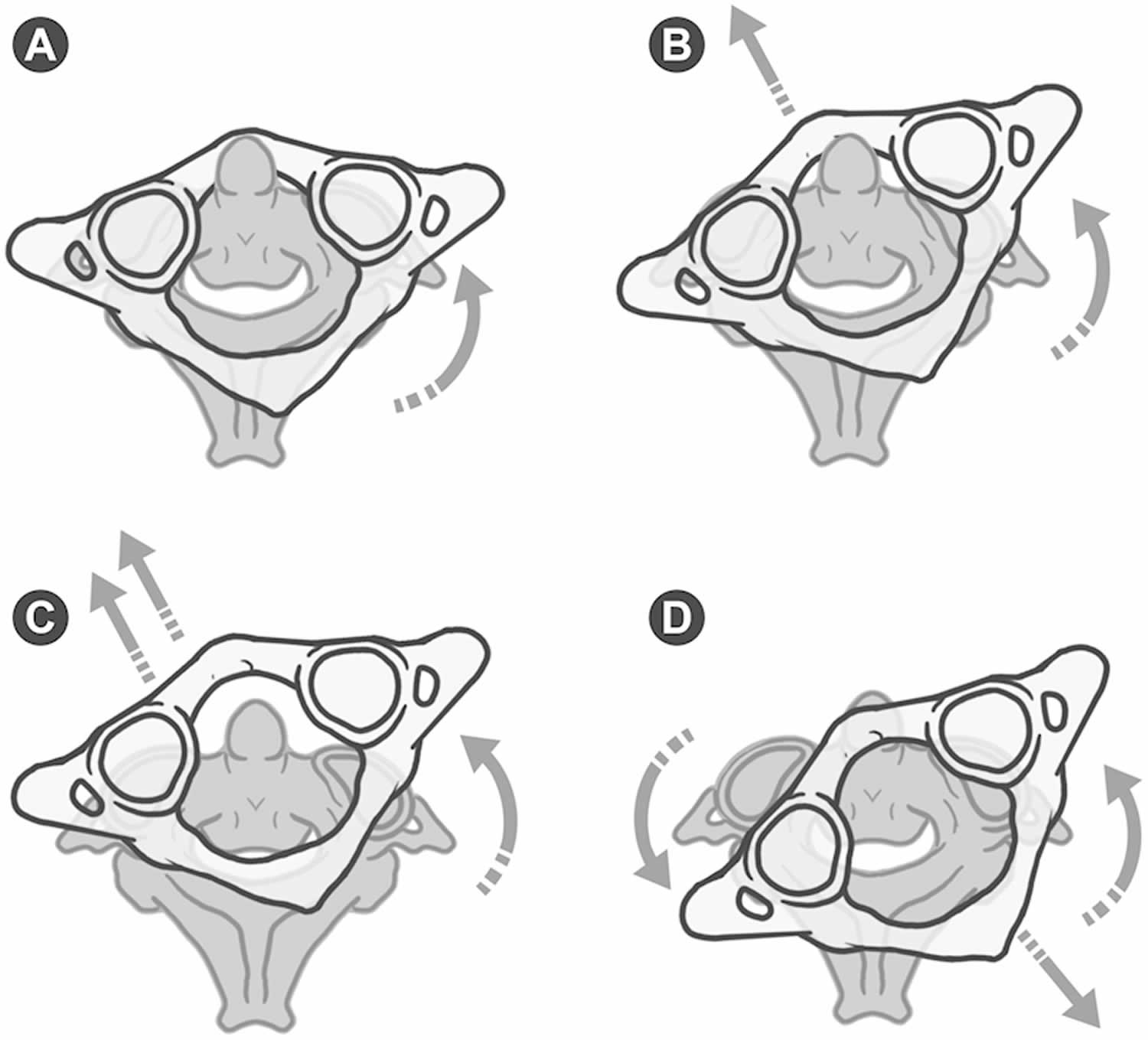

Fielding and Hawkins classified traumatic atlantoaxial rotatory subluxation into four types depending on the distance between the atlas and the odontoid process of the axis 18. In type 1, there is pure rotation of the atlas in relation to the axis and atlantodental interval (ADI) is normal. In type 2, there is both rotation and anterior dislocation of the atlas with atlantodental interval (ADI) of 3 to 5 mm, suggesting mild dysfunction of the transverse ligament. Type 3 consists of rotation and anterior dislocation of more than 5 mm, indicating complete dysfunction of the transverse ligament. Type 4 is characterized by rotation and posterior dislocation of the atlas (Figure 4). Type 1 and 2 subluxations are the most frequent and do not involve neurologic deficits, whereas types 3 and 4 may be associated with spinal cord compression and neurological injury.

Figure 4. Fielding and Hawkins traumatic atlantoaxial rotatory subluxation classification

Footnote: Schematic illustration of Fielding and Hawkins’ classification of traumatic atlantoaxial rotatory subluxation. Type 1: pure rotation of the atlas in relation to the axis without anterior displacement (A). Type 2: atlas rotated with 3- to 5-mm anterior displacement (B). Type 3: rotation of the atlas with anterior displacement greater than 5 mm (C). Type 4: rotatory fixation with posterior displacement of atlas (D).

[Source 18 ]Grisel syndrome treatment

The treatment of Grisel syndrome is controversial. Neurosurgical consultation is paramount in all cases 11. In the majority of cases conservative management in the form of bed rest, antibiotics, analgesics, nonsteroidal anti-inflammatory drugs (NSAIDs), muscle relaxants, traction, cervical collar and abscess drainage was effective 2; in a few cases only surgery in the form of C1-C2 arthrodesis (surgical immobilization of a joint by fusion of the bones) is indicated in case of failure of medical management or onset of neurologic signs 19. Morbidity was significant in those cases where diagnosis was delayed, with the most devastating consequence a permanent neurological deficit in one case.

At first, the cervical posture usually prevents the use of a rigid cervical collar. Therefore, some doctors recommend the use of a soft cervical collar molded to the height of the neck at that time. As greater relaxation of the cervical muscles occurs, the authors recommend increasing the height of the collar until reduction of the lesion occurs 13. Then, the soft collar is replaced with a rigid one. The waiting period for the occurrence of spontaneous reduction has not been established. However, most cases usually resolve spontaneously up to 7 days after the beginning of treatment 20. Once the injury is reduced and the inflammatory process is completely solved, stability is recovered. Although there is no consensus, the authors recommend the use of a rigid collar for at least 2 weeks to treat neck pain and to prevent early recurrence and the return to normal recreation and sports activities after 4 to 6 weeks 13.

If spontaneous reduction of the lesion does not occur, closed reduction under mild sedation is recommended, with analgesia in the surgical block 13. The options are: manual traction in mild flexion followed by cervical extension and contralateral rotation, Jeszenszky transoral technique consisting of locking the spinous process of the axis with one hand while pressing with the index finger of the other hand the lateral mass dislocated anteriorly through the posterior wall of the oropharynx, or halo-cranial traction 21. Definitive treatment should be instituted after reduction. Wetzel and La Rocca 22 proposed a treatment protocol for nontraumatic atlantoaxial rotatory subluxation (Grisel syndrome) based on the classification of Fielding and Hawkins. Conservative treatment for type 1, 2, and 3 lesions with a soft collar, a rigid collar (Philadelphia collar), and a halo-vest, respectively. For type 4 lesions, they recommend surgical treatment 22. Surgical treatment is indicated also in cases of failure of conservative treatment, recurrence of subluxation, and irreducible subluxations. Craniocervical fusions in children present unique challenges even in the absence of craniovertebral malformations. The diminutive osseous and ligamentous structures, especially in children younger than 5 to 6 years, limit the use of internal fixation. In these cases, Menezes 23 recommends a small craniectomy and upper cervical laminectomy with a bilateral interlaminar and occipital rib graft anchored with titanium cables. After this age, the size and anatomy of craniovertebral structures may allow the use of screw fixations such as C1–C2 transarticular screw fixation, lateral mass screws at C1, and rod fixation with either C2 pars interarticular screw fixation, pedicle screw fixation, or C2 translaminar screw fixation 23.

Grisel syndrome prognosis

In milder cases and with early diagnosis, treatment with broad spectrum antibiotics and soft collar is sufficient. Delayed diagnosis or increasing severity needs treatment with traction brace.

Residual subluxation after 8 weeks of treatment or neurological symptoms may require operative treatment.

References- Karkos PD, Benton J, Leong SC, Mushi E, Sivaji N, Assimakopoulos DA. Grisel’s syndrome in otolaryngology: a systematic review. Int J Pediatr Otorhinolaryngol. 2007;71(12):1823-1827. doi:10.1016/j.ijporl.2007.07.002

- Fernández Cornejo V J, Martínez-Lage J F, Piqueras C, Gelabert A, Poza M. Inflammatory atlanto-axial subluxation (Grisel’s syndrome) in children: clinical diagnosis and management. Childs Nerv Syst. 2003;19(5–6):342–347.

- Yamazaki M, Someya Y, Aramomi M, Masaki Y, Okawa A, Koda M. Infection-related atlantoaxial subluxation (Grisel syndrome) in an adult with Down syndrome. Spine (Phila Pa 1976) 2008;33(5):E156–E160.

- Youssef K, Daniel S. Grisel syndrome in adult patients. Report of two cases and review of the literature. Can J Neurol Sci. 2009;36(1):109–113.

- Doshi, J., Anari, S., Zammit-Maempel, I., & Paleri, V. (2007). Grisel syndrome: A delayed presentation in an asymptomatic patient. The Journal of Laryngology & Otology, 121(8), 800-802. doi:10.1017/S0022215107006263

- Das S, Chakraborty S, Das S. Grisel Syndrome in Otolaryngology: A Case Series with Literature Review. Indian J Otolaryngol Head Neck Surg. 2019;71(Suppl 1):66-69. doi:10.1007/s12070-016-1030-0

- Stilwell PA, Fine D, Roberts J, et al. A pain in the neck: Grisel’s syndrome. Archives of Disease in Childhood 2019;104:610.

- Deichmueller CM, Welkoborsky HJ. Grisel’s syndrome—a rare complication following “small” operations and infections in the ENT region. Eur Arch Otorhinolaryngol 2010;267(9):1467–1473.

- Doshi J, Anari S, Zammit-Maempel I, Paleri V. Grisel syndrome: a delayed presentation in an asymptomatic patient. J Laryngol Otol. 2007;121(8):800-802. doi:10.1017/S0022215107006263

- Nozaki F, Kusunoki T, Tomoda Y. et al.Grisel syndrome as a complication of Kawasaki disease: a case report and review of the literature. Eur J Pediatr. 2013;172(1):119–121.

- Grisel’s syndrome in otolaryngology: A systematic review. International Journal of Pediatric Otorhinolaryngology Volume 71, Issue 12, December 2007, Pages 1823-1827. https://doi.org/10.1016/j.ijporl.2007.07.002

- Falsaperla R, Piattelli G, Marino S, Marino SD, Fontana A, Pavone P. Grisel’s syndrome caused by Mycoplasma pneumoniae infection: a case report and review of the literature. Childs Nerv Syst. 2019;35(3):523-527. doi:10.1007/s00381-018-3970-z

- Nontraumatic Atlantoaxial Rotatory Subluxation: Grisel Syndrome. Case Report and Literature Review. Global Spine J. 2014 Aug; 4(3): 179–186. doi: 10.1055/s-0033-1363936 https://www.ncbi.nlm.nih.gov/pmc/articles/PMC4111947

- Subach B R, McLaughlin M R, Albright A L, Pollack I F. Current management of pediatric atlantoaxial rotatory subluxation. Spine (Phila Pa 1976) 1998;23(20):2174–2179.

- Rinaldo A, Mondin V, Suárez C, Genden E M, Ferlito A. Grisel’s syndrome in head and neck practice. Oral Oncol. 2005;41(10):966–970.

- Yu K K, White D R, Weissler M C, Pillsbury H C. Nontraumatic atlantoaxial subluxation (Grisel syndrome): a rare complication of otolaryngological procedures. Laryngoscope. 2003;113(6):1047–1049.

- Diethelm L, Heuck F, Olsson O, Berlin, Germany: Springer Verlag; 1976. Handbuch der medizinischen Radiologie [Encyclopedia of Medical Radiology] p. 195.

- Fielding J W, Hawkins R J. Atlanto-axial rotatory fixation (fixed rotatory subluxation of the atlanto-axial joint) J Bone Joint Surg Am. 1977;59(1):37–44.

- Fath L, Cebula H, Santin MN, Coca A, Debry C, Proust F. The Grisel’s syndrome: A non-traumatic subluxation of the atlantoaxial joint. Neurochirurgie. 2018;64(4):327-330. doi:10.1016/j.neuchi.2018.02.001

- Phillips W A, Hensinger R N. The management of rotatory atlanto-axial subluxation in children. J Bone Joint Surg Am. 1989;71(5):664–668.

- Park S W, Cho K H, Shin Y S. et al.Successful reduction for a pediatric chronic atlantoaxial rotatory fixation (Grisel syndrome) with long-term halter traction: case report. Spine (Phila Pa 1976) 2005;30(15):E444–E449.

- Wetzel F T, La Rocca H. Grisel’s syndrome. Clin Orthop Relat Res. 1989;(240):141–152.

- Menezes A H. Craniocervical fusions in children. J Neurosurg Pediatr. 2012;9(6):573–585.