Infant respiratory distress syndrome

Infant respiratory distress syndrome also known as newborn respiratory distress syndrome, hyaline membrane disease or surfactant deficiency lung disease, is a lung condition causing breathing problems in newborn premature infants. Respiratory distress syndrome in newborn happens when a baby’s lungs are not fully developed and cannot provide enough oxygen, causing breathing difficulties. Infant respiratory distress syndrome usually affects premature babies.

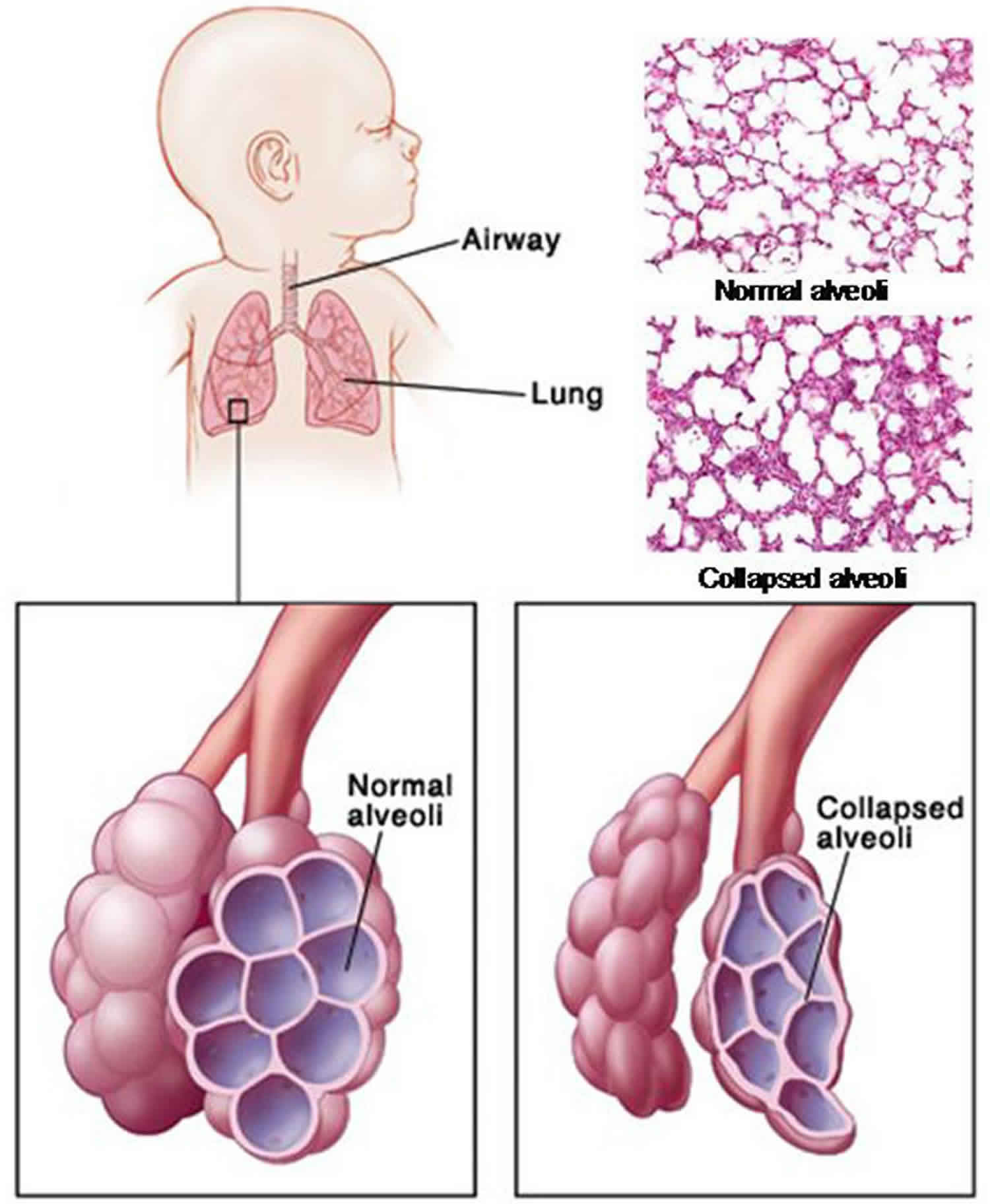

Newborn respiratory distress syndrome occurs when there is not enough of a substance in the lungs called surfactant. Surfactant is made by the cells in the airways and consists of phospholipids and protein. Surfactant begins to be produced in the fetus at about 24 to 28 weeks of pregnancy, and is found in amniotic fluid between 28 and 32 weeks. By about 35 weeks gestation, most babies have developed adequate amounts of surfactant. Surfactant helps to keep the alveoli from collapsing once they are inflated. In the lungs, the exchange of oxygen and carbon dioxide takes place in the alveoli (small air sacs).

Newborn respiratory distress syndrome is most common in premature infants who are 30 weeks gestation or younger. Because a baby’s lungs are not needed for breathing until after birth, they are one of the last organs to fully develop. The more premature the birth, the less able your baby’s lungs are to function well.

A baby’s first breath requires a big effort to open the alveoli and fill them with air for the first time. Without surfactant, each breath continues to require a great effort because the alveoli don’t stay open. The infant soon tires and has trouble breathing.

After birth, the baby’s lungs may take up to 5 days to produce surfactant.

Treatment for newborn respiratory distress syndrome may include:

- placing an endotracheal tube (breathing tube, also called an ET) into your baby’s windpipe

- mechanical breathing machine (to do the work of breathing for your baby)

- supplemental oxygen (extra amounts of oxygen)

continuous positive airway pressure (CPAP) – a mechanical breathing machine that pushes a continuous flow of air or oxygen to the airways to help keep tiny air passages in the lungs open - surfactant replacement with artificial surfactant – this treatment has been shown to reduce the severity of newborn respiratory distress syndrome, and is most effective if started in the first six hours of birth. It may be given as preventive treatment for babies at very high risk for newborn respiratory distress syndrome, or used as a “rescue” method. The drug comes as a powder that is mixed with sterile water and given through the endotracheal tube tube. This treatment is usually administered in several doses.

- medications (to help sedate and ease your baby’s pain during treatment)

Infant respiratory distress syndrome key points:

- Newborn respiratory distress syndrome is one of the most common problems seen in premature babies.

- The more premature the baby, the higher the risk and the more severe the newborn respiratory distress syndrome.

- Newborn respiratory distress syndrome typically worsens over the first 48 to 72 hours and then improves with treatment.

- More than 90 percent of babies with newborn respiratory distress syndrome survive.

- The best way of preventing newborn respiratory distress syndrome is by preventing a preterm birth. When a preterm birth cannot be prevented, giving the mother medications called corticosteroids before delivery has been shown to dramatically lower the risk and severity of newborn respiratory distress syndrome in the baby. These steroids are often given to women between 24 and 34 weeks gestation who are at risk of early delivery.

What does surfactant do?

In healthy lungs, surfactant is released into the lung tissues where it helps lower surface tension in the airways, which helps keep the lung alveoli (air sacs) open. When there is not enough surfactant, the tiny alveoli collapse with each breath. As the alveoli collapse, damaged cells collect in the airways, which makes it even harder to breath. These cells are called hyaline membranes. Your baby works harder and harder at breathing, trying to re-inflate the collapsed airways.

As your baby’s lung function decreases, less oxygen is taken in and more carbon dioxide builds up in the blood. This can lead to acidosis (increased acid in the blood), a condition that can affect other body organs. Without treatment, your baby becomes exhausted trying to breathe and eventually gives up. A mechanical ventilator (breathing machine) must do the work of breathing instead.

What factors determine how newborn respiratory distress syndrome progresses?

The course of illness with newborn respiratory distress syndrome depends on the size and gestational age of your baby, the severity of the disease, the presence of infection, whether or not your baby has a patent ductus arteriosus (a heart condition) and whether or not she needs mechanical help to breathe.

Infant respiratory distress syndrome causes

Neonatal newborn respiratory distress syndrome occurs in infants whose lungs have not yet fully developed.

The disease is mainly caused by a lack of a slippery substance in the lungs called surfactant. This substance helps the lungs fill with air and keeps the air sacs from deflating. Surfactant is present when the lungs are fully developed.

Neonatal respiratory distress syndrome can also be due to genetic problems with lung development.

Most cases of newborn respiratory distress syndrome occur in babies born before 37 to 39 weeks. The more premature the baby is, the higher the chance of newborn respiratory distress syndrome after birth. The problem is uncommon in babies born full-term (after 39 weeks).

Other factors that can increase the risk of newborn respiratory distress syndrome include:

- A brother or sister who had newborn respiratory distress syndrome

- Diabetes in the mother

- Cesarean delivery or induction of labor before the baby is full-term

- Problems with delivery that reduce blood flow to the baby

- Multiple pregnancy (twins or more)

- Rapid labor.

Who is affected by newborn respiratory distress syndrome?

Newborn respiratory distress syndrome occurs in about 60 to 80 percent of babies born before 28 weeks gestation, but only in 15 to 30 percent of those born between 32 and 36 weeks. About 25 percent of babies born at 30 weeks develop newborn respiratory distress syndrome severe enough to need a mechanical ventilator (breathing machine).

Although most babies with newborn respiratory distress syndrome are premature, other factors can influence the chances of developing the disease. These include the following:

- Caucasian or male babies

- Previous birth of baby with newborn respiratory distress syndrome

- Cesarean delivery

- Perinatal asphyxia (lack of air immediately before, during or after birth)

- Cold stress (a condition that suppresses surfactant production)

- Perinatal infection

- Multiple births (multiple birth babies are often premature)

- Infants of diabetic mothers (too much insulin in a baby’s system due to maternal diabetes can delay surfactant production)

- Babies with patent ductus arteriosus

Infant respiratory distress syndrome prevention

Taking steps to prevent premature birth can help prevent neonatal respiratory distress syndrome. Good prenatal care and regular checkups beginning as soon as a woman discovers she is pregnant can help avoid premature birth.

The risk of newborn respiratory distress syndrome can also be lessened by the proper timing of delivery. An induced delivery or cesarean may be needed. A lab test can be done before delivery to check the readiness of the baby’s lungs. Unless medically necessary, induced or cesarean deliveries should be delayed until at least 39 weeks or until tests show that the baby’s lungs have matured.

Medicines called corticosteroids can help speed up lung development before a baby is born. They are often given to pregnant women between 24 and 34 weeks of pregnancy who seem likely to deliver in the next week. More research is needed to determine if corticosteroids may also benefit babies who are younger than 24 or older than 34 weeks.

At times, it may be possible to give other medicines to delay labor and delivery until the steroid medicine has time to work. This treatment may reduce the severity of newborn respiratory distress syndrome. It may also help prevent other complications of prematurity. However, it will not totally remove the risks.

Infant respiratory distress syndrome symptoms

Most of the time, neonatal respiratory distress syndrome symptoms appear within minutes of birth. However, they may not be seen for several hours.

While each baby may experience symptoms differently, some of the most common symptoms of newborn respiratory distress syndrome include:

- Breathing too fast or too slow

- Shallow breathing

- Flaring of the nostrils with breaths

- Unusual breathing movement (such as drawing back of the chest muscles with breathing) or retractions (chest skin pulls in with breaths)

- Chest may collapse with each breath

- Grunting when breathing out

- Skin color may be pale, bluish (cyanosis) or gray

- Brief stop in breathing (apnea)

- Decreased urine output

- Shortness of breath and grunting sounds while breathing.

Symptoms of newborn respiratory distress syndrome usually peak by the third day and may resolve quickly when your baby begins to diurese (excrete excess water in urine) and needs less oxygen and mechanical help to breathe.

Infant respiratory distress syndrome possible complications

Your baby may develop complications of the infant respiratory distress syndrome or problems as side effects of treatment. As with any disease, more severe cases often have greater risks for complications.

Some complications associated with newborn respiratory distress syndrome include the following:

Air or gas may build up in:

- Air leaks into the space between the chest wall and the outer tissues of the lungs (pneumothorax)

- Air leaks into the mediastinum (the space between the two pleural sacs containing the lungs) (pneumomediastinum)

- Air leaks into the area between the heart and the thin sac that surrounds the heart (pneumopericardium)

- Air leaks and becomes trapped between the alveoli, the tiny air sacs of the lungs (pulmonary interstitial emphysema)

Other conditions associated with newborn respiratory distress syndrome or extreme prematurity may include:

- Bleeding into the brain (intraventricular hemorrhage of the newborn) – Bleeding into the brain is quite common in premature babies, but most bleeds are mild and do not cause long-term problems.

- Bleeding into the lung (pulmonary hemorrhage; sometimes associated with surfactant use) – Bleeding into the lungs is treated with air pressure from a ventilator to stop the bleeding and a blood transfusion.

- Problems with lung development and growth (bronchopulmonary dysplasia)

- Sometimes ventilation (begun within 24 hours of birth) or the surfactant used to treat newborn respiratory distress syndrome causes scarring to the baby’s lungs, which affects their development. This lung scarring is called bronchopulmonary dysplasia. Symptoms of bronchopulmonary dysplasia include rapid, shallow breathing and shortness of breath. Babies with severe bronchopulmonary dysplasia usually need additional oxygen from tubes into their nose to help with their breathing. This is usually stopped after a few months, when the lungs have healed. But children with bronchopulmonary dysplasia may need regular medication, such as bronchodilators, to help widen their airways and make breathing easier.

- Delayed development or intellectual disability associated with brain damage or bleeding. If the baby’s brain is damaged during newborn respiratory distress syndrome, either because of bleeding or a lack of oxygen, it can lead to long-term developmental disabilities, such as learning difficulties, movement problems, impaired hearing and impaired vision. But these developmental problems are not usually severe. For example, 1 survey estimated that 3 out of 4 children with developmental problems only have a mild disability, which should not stop them leading a normal adult life.

- Problems with eye development (retinopathy of prematurity) and blindness

Newborn respiratory distress syndrome diagnosis

The following tests are used to detect respiratory distress in babies:

- Blood gas analysis — shows low oxygen and excess acid in the body fluids.

- Chest x-ray — shows a “ground glass” appearance to the lungs that is typical of the disease. This often develops 6 to 12 hours after birth.

- Echocardiography (EKG) – may be used to rule out heart problems that could cause symptoms similar to newborn respiratory distress syndrome. An electrocardiogram is a test that records the electrical activity of the heart, shows arrhythmias (abnormal rhythms) and detects damage to the heart muscle.

- Lab tests — help to rule out infection as a cause of breathing problems.

Infant respiratory distress syndrome treatment

Treatment before birth

If you’re thought to be at risk of giving birth before week 34 of pregnancy, treatment for newborn respiratory distress syndrome can begin before birth.

You may have a steroid injection before your baby is delivered. A second dose is usually given 24 hours after the first.

The steroids stimulate the development of the baby’s lungs. It’s estimated that the treatment helps prevent newborn respiratory distress syndrome in a third of premature births.

You may also be offered magnesium sulphate to reduce the risk of developmental problems linked to being born early.

If you take magnesium sulphate for more than 5 to 7 days or several times during your pregnancy, your newborn baby may be offered extra checks. This is because prolonged use of magnesium sulphate in pregnancy has in rare cases been linked to bone problems in newborn babies.

Treatment after the birth

Babies who are premature or have other conditions that make them at high risk for the infant respiratory distress syndrome need to be treated at birth by a medical team that specializes in newborn breathing problems. Your baby may be transferred to a ward that provides specialist care for premature babies (a neonatal unit).

Treatment will depend on how ill the infant is.

- If the symptoms are mild, they may only need extra oxygen. It’s usually given through an incubator or tubes into their nose.

- If symptoms are more severe, your baby will be attached to a breathing machine (ventilator) to either support or take over their breathing.

Extra oxygen may be needed. A ventilator (breathing machine) may also be needed to deliver oxygen and help remove carbon dioxide from your baby’s lungs. However, this treatment needs to be monitored carefully to avoid side effects from too much oxygen.

Assisted ventilation with a ventilator (breathing machine) can be lifesaving for some babies. However, use of a breathing machine can damage the lung tissue, so this treatment should be avoided if possible. Babies may need this treatment if they have:

- High level of carbon dioxide in the blood

- Low blood oxygen

- Low blood pH (acidity)

- Repeated pauses in breathing

A treatment called continuous positive airway pressure (CPAP) may prevent the need for assisted ventilation or surfactant in many babies. CPAP sends air into the nose to help keep the airways open. It can be given by a ventilator (while the baby is breathing independently) or with a separate CPAP device.

As babies get better, they are weaned from the oxygen or ventilator over several days. Some infants may continue to need extra oxygen. Most infants are soon breathing on their own and doing well.

A heart monitor will be used, and blood tests and chest X-rays will be done.

Artificial surfactant may be given in some situations to expand the lungs. Giving extra surfactant to a sick infant has been shown to be helpful. However, the surfactant is delivered directly into the baby’s airway, so some risk is involved. More research still needs to be done on which babies should get this treatment and how much to use.

The American Academy of Pediatrics 2014 guidelines recommend immediate management of all preterm infants with nasal continuous positive airway pressure 1. Subsequently, in selected patients, surfactant administration may be considered as an alternative to intubation with prophylactic or early surfactant administration. The surfactant replacement therapy is administered by trained personnel, in a clinical setting where equipment for intubation and resuscitation are readily available.

Endotracheal installation of surfactant is the most widely accepted technique. Surfactant is administered in liquid form via an endotracheal tube in a single bolus dose as quickly as the neonate tolerates. Some studies recommend the administration of all the surfactant at once while others advocate dividing the bolus into smaller aliquots.

Another technique of administration known as the INSURE technique is approached with the neonate not already intubated. The INSURE technique uses an in-out intubation procedure to administer the surfactant. This process includes intubation, followed by administration of the drug, and then extubation. Newer methods to limit the invasiveness of older approaches are in practice and targets of research today 2. One such technique is known as the Minimally Invasive Surfactant Therapy or MIST 3. The MIST method connects the patient to non-invasive respiratory support, and through that, the surfactant administration is with the work of spontaneous breathing. This method is increasingly being used to reduce intubation rates and their associated pathologies. Another method is the less invasive surfactant administration or LISA technique 4. This method utilizes a thin catheter for surfactant delivery, which serves to reduce the possibility of lung injury as is possible with intubation. At present, five surfactants (Lucinactant, colfosceril palmitate, beractant, calefacient, and protectant alfa) have FDA approval. Colfosceril palmitate is no longer commercially available. Lucinactant is the first U.S. FDA-approved protein-containing synthetic surfactant.

The usage of surfactant can lead to bradycardia and hypotension in the neonate. There are also some reports of instances of oxygen desaturation upon administration of the drug. Also, because conventional methods of surfactant administration require an endotracheal tube, certain risks are associated with tubal administration of any drug. Hygiene is of vital importance, especially in neonates as their immunities are underdeveloped. Infections and sepsis can occur if measures are not taken to prevent them. Unless the neonate is already intubated, intubation must take place first, which presents with the risk of injury and air leaks. Intubation also poses the risk of airway obstruction, mechanical damage to the airway, and it may require frequent suctioning. There is a risk of alterations in cerebral flow and hypoxemia. Concomitant administration of oxygen can damage lung tissue from oxygen pressure. Excess oxygenation and subsequent cessation of it leads to diseases like bronchopulmonary dysplasia and retrolental fibroplasia in infants as well 5.

Since surfactant extraction is from animal sources, a risk of immune activation exists. Rarely the drug can lead to pneumothorax and/or pulmonary hemorrhage. Other side effects may include intraventricular hemorrhage, patent ductus arteriosus, retinopathy, necrotizing enterocolitis, and/or blockage of the endotracheal tube can cause complications as well.

Babies with newborn respiratory distress syndrome need close care. This includes:

- Having a calm setting

- Gentle handling

- Staying at an ideal body temperature

- Carefully managing fluids and nutrition

- Treating infections right away

How long will it take for my baby to get well?

There are many reasons why some babies recover faster than others. Infants who are on ventilators for a long time may develop changes in their lungs. This may increase the time they need ventilator support. Other factors such as infection can also affect recovery. Each baby responds and recovers in a unique way.

Infant respiratory distress syndrome prognosis

Infant respiratory distress syndrome often gets worse for 2 to 4 days after birth and improves slowly after that. Some infants with severe respiratory distress syndrome will die. This most often occurs between days 2 and 7.

Long-term complications may develop due to:

- Too much oxygen.

- High pressure delivered to the lungs.

- More severe disease or immaturity. newborn respiratory distress syndrome can be associated with inflammation that causes lung or brain damage.

- Periods when the brain or other organs did not get enough oxygen.

- Khawar H, Marwaha K. Surfactant. [Updated 2019 Sep 12]. In: StatPearls [Internet]. Treasure Island (FL): StatPearls Publishing; 2019 Jan-. Available from: https://www.ncbi.nlm.nih.gov/books/NBK546600

- Canals Candela FJ, Vizcaíno Díaz C, Ferrández Berenguer MJ, Serrano Robles MI, Vázquez Gomis C, Quiles Durá JL. [Surfactant replacement therapy with a minimally invasive technique: Experience in a tertiary hospital]. An Pediatr (Barc). 2016 Feb;84(2):79-84.

- Kribs A. Minimally Invasive Surfactant Therapy and Noninvasive Respiratory Support. Clin Perinatol. 2016 Dec;43(4):755-771.

- Aldana-Aguirre JC, Pinto M, Featherstone RM, Kumar M. Less invasive surfactant administration versus intubation for surfactant delivery in preterm infants with respiratory distress syndrome: a systematic review and meta-analysis. Arch. Dis. Child. Fetal Neonatal Ed. 2017 Jan;102(1):F17-F23.

- Foglia EE, Jensen EA, Kirpalani H. Delivery room interventions to prevent bronchopulmonary dysplasia in extremely preterm infants. J Perinatol. 2017 Nov;37(11):1171-1179.