Pulmonary aspiration

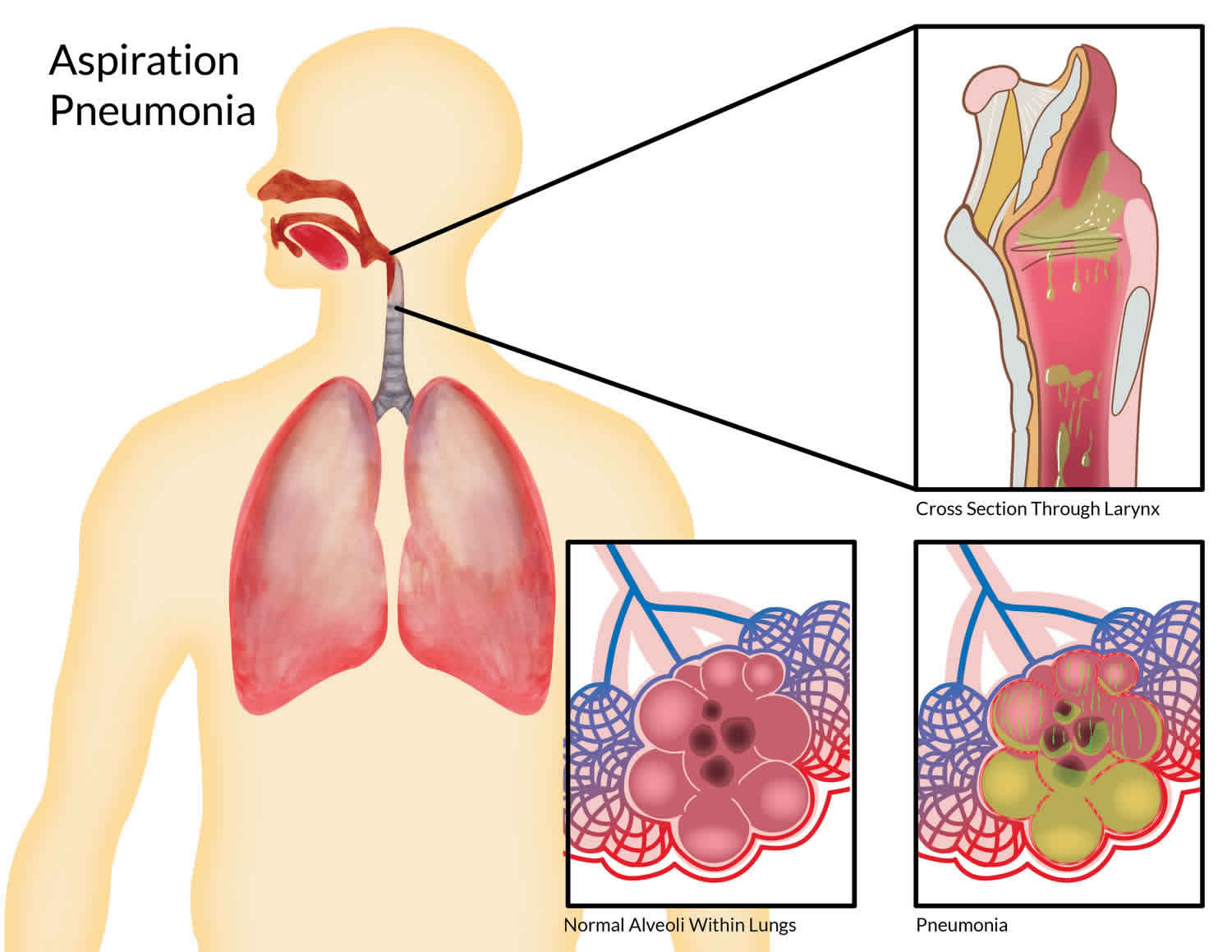

Pulmonary aspiration is the entry of secretions or foreign material into your trachea and lungs. The patient may either inhale the material, or it may be blown into the lungs during positive pressure ventilation or CPR. As the right main bronchus is more vertical and of slightly wider lumen than the left, aspirated material is more likely to end up in this branch or one of its subsequent bifurcations. Failure of the natural defense mechanisms like the closure of glottis and cough reflex increases the risk of pulmonary aspiration. The common risk factors for pulmonary aspiration include altered mental status, neurologic disorders, esophageal motility disorders, protracted vomiting, and gastric outlet obstruction 1.

Pulmonary aspiration can affect any age group, but the youngest and oldest are at highest risk because of a higher incidence of risk factors. Pulmonary aspiration affects both genders equally.

The exact number of individuals who develop aspiration pneumonia is not known but they are not minuscule. It is believed that at least 10-15% of patients hospitalized develop aspiration pneumonitis as a result of a drug overdose, stroke, and other central nervous system (CNS) pathology 2.

Pulmonary aspiration is common, even in healthy patients. Pulmonary aspiration can have significant morbidity and mortality in certain circumstances. Pulmonary aspiration is categorized based on the predominant material in the aspirate. If oropharyngeal secretions, orally ingested material, or partially digested gastric contents are aspirated, one would expect infectious pneumonia to develop. However, if pure gastric secretions are aspirated, then a chemical pneumonitis is the result. If partially digested gastric contents are aspirated along with some gastric acid, a mixture of chemical pneumonitis and inoculation of the lungs with potentially pathogenic organisms can occur. In practice, it is prudent to treat a chemical pneumonitis with prophylactic antibiotics because a superimposed infection occurs in over 25% of cases. It is difficult to determine the quality of the aspirate in most cases, and a combination of bacterial and chemical injury is common 3.

The treatment varies between aspiration pneumonia and aspiration pneumonitis. To prevent further aspiration, patient’s position should be adjusted followed by suction of oropharyngeal contents with the placement of the nasogastric tube. In patients who are not intubated humidified oxygen is administered and the head end of the bed should be raised by 45 degrees. A close monitoring of patients oxygen saturation is important and immediate intubation with mechanical ventilation should be provided if hypoxia is noted. A flexible bronchoscopy is usually indicated for large volume aspiration to clear the secretion and also for obtaining the sample of bronchoalveolar lavage for quantitative bacteriological studies. In general practice, antibiotics are initiated immediately even though are not required in aspiration pneumonitis to prevent progression of the disease. The choice of antibiotics for community-acquired aspiration pneumonia are ampicillin-sulbactam, or a combination of metronidazole and amoxicillin can be used. In patients with penicillin allergy clindamycin is preferred. However, in hospital-acquired aspiration pneumonia antibiotics that cover resistant gram-negative bacteria and S.aureus; so the use of a combination of vancomycin and piperacillin-tazobactam is most widely used. Once the culture results are obtained the antibiotic regimen should be narrowed to organism-specific 4.

Oxygenation is often needed and some patients may even require mechanical ventilation.

Pulmonary aspiration causes

Risk factors for pulmonary aspiration 2:

- Cognitive Neurologic impairment: This can be due to stroke, seizure, intoxication, developmental delay or any other cognitive impariment

- Focal Neurologic impariment: This is related to history of stroke, cranial nerve injury, pharyngeal muscle injury.

- Pulmonary disease: This includes patients who require mechanical ventilation for any reason, patients with a poor cough, or poor forced expiratory volume.

- Supraglottic disease: This includes patients with anatomic irregularities in the oropharynx, poor dental hygiene, or disease states which cause esophageal dysmotility and impaired swallowing.

- Other causes: Position changes can lead to aspiration even in healthy patients. Fifty percent of healthy individuals have silent aspiration during sleep identified by radio-markers. Frequent, high-volume vomiting is another potential risk factor. Also, proton pump inhibition which changes the gastric pH, and subsequently the gastric flora, allowing overgrowth of potentially harmful microorganisms 5. Analgesia of the pharynx and/or larynx, patients undergoing any oral, esophageal or airway procedure, and trauma patients.

- Mechanical. When patients have an nasogastric tube, tracheostomy, upper endoscopy, bronchoscopy or a gastrostomy feeding tube, they are at a risk for aspiration.

Conditions that increase the risk of aspiration pneumonia include 1:

- Stroke

- Drug overdose

- Alcoholism

- Seizures

- General anesthesia

- Head trauma

- Intracranial masses

- Dementia

- Parkinson disease

- Esophageal strictures

- Gastroesophageal reflux disease (GERD)

- Pseudobulbar palsy

- Tracheostomy

- Nasogastric tube

- Bronchoscopy

- Protracted vomiting

Healthy people in the community can tolerate small pulmonary aspiration events without significant complications. However, micro-aspiration has been implicated in the pathogenesis of ventilator-associated pneumonia 2. Several factors may contribute to this. Ventilated patients have significant disease states that may predispose them to a superimposed infection. It should be noted that the endotracheal tube cuff, or tracheostomy tube cuff, does not protect from micro-aspiration, even when properly inflated. The use of endotracheal tubes with aspiration ports proximal to the cuff and connected to continuous suction have successfully decreased the risk of ventilator-associated pneumonia but have not completely stopped its occurrence. It is prudent to use this for patients that are not expected to be weaned from the ventilator early.

Another important consideration is the widespread use of proton pump inhibitors in the intensive care unit (ICU) population. The use of these agents for peptic ulcer prophylaxis is ubiquitous and changes the gastric pH to a less acidic environment. This change in gastric pH leads to a change in the gastric flora, which favors pathogenic organisms over the normal colonizers. With micro-aspiration, this increases the likelihood of pathogenic organisms getting entry into the bronchial tree 1.

Chemical pneumonitis occurs when a significant amount of gastric content is aspirated. This fluid devoid of bacteria can cause severe respiratory distress within 60 minutes. The acidic fluid results in severe damage to the upper and lower airways.

The entry of fluid into the bronchi and alveolar space triggers an anti-inflammatory reaction with the release of proinflammatory cytokines, tumor necrosis factor alpha, and Interleukins. Inoculation of organisms of common flora from the oropharynx and esophagus results in the infectious process. Mendelson first studied the pathophysiology of aspiration pneumonitis by inducing gastric contents in rabbit’s lung and comparing to 0.1N hydrochloric acid. Later studies conducted in rats using diluted hydrochloric acid demonstrated the biphasic response with initial corrosive phase by acidic pH followed by a neutrophil-mediated inflammatory response. Inoculation of normal oropharyngeal flora in the aspirate results in infectious process and results in aspiration pneumonia. If the bacterial load of aspirate is low normal host defenses will clear the secretions and prevent infection.

When patients develop aspiration pneumonia, the predominant organisms are anaerobes but one may also find gram-positive and gram-negative pathogens. Today, MRSA is widely reported to be the cause of aspiration pneumonia in the community.

Pulmonary aspiration symptoms

The common clinical features that should raise suspicion for pulmonary aspiration include sudden onset shortness of breath (dyspnea), coughing, fever, low oxygen saturation (hypoxemia), radiological findings of bilateral infiltrates and crackles on lung auscultation in a hospitalized patient. The common site involved depends on the position at the time of aspiration, commonly the lower lobes are involved in an upright position, and superior lobes can be involved in the recumbent position. The radiological findings will develop within 2 hours after aspiration and bronchoscopy can reveal erythematous bronchi.

The pertinent physical findings include tachypnea, low oxygen saturation, rhonchi, rales, and the absence of breath sounds if an obstruction occurs. In obtunded patients, aspiration may be an ongoing process rather than a single event. History is important as both inpatients and outpatients may have had a witnessed aspiration or developed acute shortness of breath.

Pulmonary aspiration complications

- Lung abscess

- Empyema

- Bronchopleural fistula

- Acute respiratory distress syndrome (ARDS)

Pulmonary aspiration diagnosis

Get a chest x-ray to determine the extent of the pulmonary aspiration. With sufficiently large aspirations, it may become necessary to perform bronchoscopy and bronchoalveolar lavage to clear as much macroscopic material as possible. Perform a swallow evaluation and barium swallow study on any patient at risk for pulmonary aspiration, by a speech therapist. In young children, this is done under fluoroscopy. Dietary alterations, such as thickened liquids or pureed diets, can help patients with functional swallowing disorders 6.

The blood gas can provide details about oxygenation and pH status. In addition, lactate levels can be used as a marker of shock.

Levels of electrolytes, blood urea nitrogen (BUN), and creatinine can be used to assess renal function and fluid status. The complete blood count (CBC) may reveal leucocytosis, anemia, and thrombocytosis.

The value of sputum culture and gram stain is limited because of contamination. Blood cultures are often not positive and not useful for initial management.

The chest x-ray is important as it can provide information on patient position when aspiration occurred. The right lower lobe is the most common site for aspiration because of its vertical orientation. Individuals who aspirate while upright may have bilateral lower lobe infiltrates. Those lying in the left lateral decubitus position may have left-sided infiltrates. The upper lobe is classically involved when the patient aspirates in the prone position. This is often seen in alcoholics. Some patients may develop a parapneumonic effusion, which can be aspirated for culture and gram stain.

CT scan is not routine but may be required if the patient is not improving and there is suspicion of an empyema or a cavitary lesion with necrosis.

Bronchoscopy is usually indicated in chemical pneumonitis when food or foreign material has been aspirated. The technique can also help retrieve samples for culture and can detect any bronchial obstruction.

Pulmonary aspiration treatment

It is important to determine the type of aspiration that has occurred. If a chemical pneumonitis is suspected, supportive therapy should be initiated. Depending on the overall health status of the patient, intubation may or may not be necessary and should be guided by the clinical picture. It should be noted that chemical pneumonitis may progress very rapidly and commonly leads to acute respiratory distress syndrome. As noted earlier, most cases are not purely chemical or bacterial, so prophylactic antibiotics should be instituted until definitive evidence exists that there is no infectious component 7.

If large particles of food or other oral or gastric content enters the bronchial tree, it may require bronchoscopy to alleviate the obstruction of the airways. Any obstruction should be removed as quickly as possible to allow the normal physiologic mechanisms to mobilize secretions and infectious particles.

If the aspiration leads to bacterial pneumonia, appropriate cultures should be obtained and broad-spectrum antibiotics instituted. Once culture sensitivities are available, more directed antibiotic therapy can be used.

Patients at high risk for aspiration should have precautions put in place to reduce the risk. These precautions are dependent on the predisposing risk factors for any individual. Patients unable to contribute to their oral hygiene should have an oral cleansing program provided. This can be accomplished using chlorhexidine oral swabs twice daily, especially in chronically intubated patients. In the intubated patient, it is important to place the patient in a semi-recumbent position (head up 45 degrees) rather than supine, as long as it is not contraindicated. If ventilatory support is expected to be longer than 48 to 72 hours, an endotracheal tube with subglottic suction capability should be placed, and either continuous or intermittent suction should be utilized.

Hemodynamic compromise is common in aspiration pneumonia and patients may require ICU monitoring and inotropic support.

Debilitated and neurologically impaired patients should be fed in an upright position, and a swallow evaluation should be done by a speech therapist or nutritionist to determine the proper consistency of food and liquids. For those unable to tolerate oral intake, a percutaneous endoscopic gastrostomy tube (PEG tube) or jejunostomy tube (J-tube) should be considered if recovery is expected to be protracted.

Pulmonary aspiration prognosis

The prognosis of pulmonary aspiration is highly variable and dependent on a number of factors. Patients in good health before the event, small volume aspiration, and better pulmonary reserve tend to have a more favorable outcome. Patients with poor host defenses, recurrent aspiration events, large-volume acid aspiration, and underlying pulmonary disease may poorly tolerate the insult. The majority of inpatient management should be focused on prevention when possible. The mortality rate for aspiration pneumonia varies from 10-50%. Any delay in diagnosis or treatment usually leads to high mortality.

References- Sanivarapu RR, Gibson JG. Aspiration Pneumonia. [Updated 2019 Sep 29]. In: StatPearls [Internet]. Treasure Island (FL): StatPearls Publishing; 2019 Jan-. Available from: https://www.ncbi.nlm.nih.gov/books/NBK470459

- Kollmeier BR, Keenaghan M. Aspiration Risk. [Updated 2019 Oct 29]. In: StatPearls [Internet]. Treasure Island (FL): StatPearls Publishing; 2019 Jan-. Available from: https://www.ncbi.nlm.nih.gov/books/NBK470169

- Lyons PG, Kollef MH. Prevention of hospital-acquired pneumonia. Curr Opin Crit Care. 2018 Oct;24(5):370-378.

- Barrett Mørk FC, Gade C, Thielsen M, Frederiksen MS, Arpi M, Johannesen J, Jimenez-Solem E, Holst H. Poor compliance with antimicrobial guidelines for childhood pneumonia. Dan Med J. 2018 Nov;65(11).

- Lee AS, Ryu JH. Aspiration Pneumonia and Related Syndromes. Mayo Clin. Proc. 2018 Jun;93(6):752-762.

- Son YG, Shin J, Ryu HG. Pneumonitis and pneumonia after aspiration. J Dent Anesth Pain Med. 2017 Mar;17(1):1-12.

- Jam R, Mesquida J, Hernández Ó, Sandalinas I, Turégano C, Carrillo E, Pedragosa R, Valls J, Parera A, Ateca B, Salamero M, Jane R, Oliva JC, Delgado-Hito P. Nursing workload and compliance with non-pharmacological measures to prevent ventilator-associated pneumonia: a multicentre study. Nurs Crit Care. 2018 Nov;23(6):291-298.