Intestinal malrotation

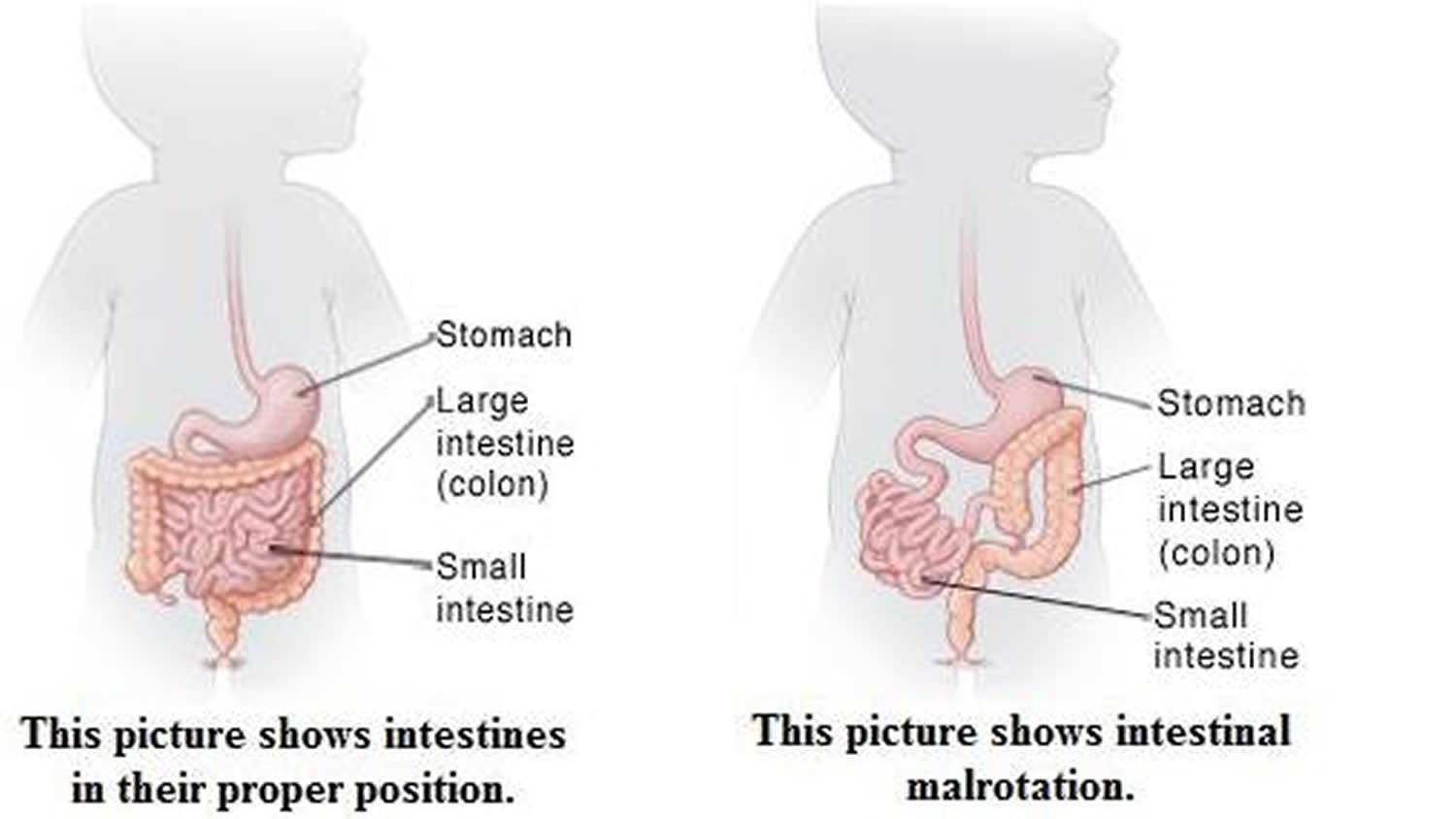

Intestinal malrotation is an abnormality that can happen early in pregnancy when a baby’s intestines don’t form into a coil in the abdomen. Malrotation means that the intestines (or bowel) are twisting, which can cause obstruction (blockage). Some children with intestinal malrotation never have problems and the condition isn’t diagnosed. But most develop symptoms and are diagnosed by 1 year of age. Intestinal malrotation most often isn’t a problem by itself. But it makes a child more likely to have a volvulus (twisted intestine). A volvulus can be very dangerous. That’s why intestinal malrotation needs to be treated, even if your child has no symptoms. Although surgery is needed to repair malrotation, most kids will go on to grow and develop normally after treatment.

Intestinal malrotation occurs in between 1 in 200 and 1 in 500 live births 1. However, most patients with malrotation are asymptomatic, with symptomatic malrotation occurring in only 1 in 6000 live births 2. Symptoms and diagnosis may occur at any age, with some reports of prenatal diagnosis of intestinal malrotation 3. Male predominance is observed in neonatal presentations at a male-to-female ratio of 2:1. No sexual predilection is observed in patients older than 1 year.

Malrotation may occur as an isolated anomaly or in association with other congenital anomalies; 30-62% of children with malrotation have an associated congenital anomaly. All children with diaphragmatic hernia, gastroschisis, and omphalocele have intestinal malrotation by definition. Additionally, malrotation is seen in approximately 17% of patients with duodenal atresia and 33% of patients with jejunoileal atresia 4.

While a baby is still in the womb, its intestines (bowels) form. During normal abdominal development, the 3 divisions of the gastrointestinal tract (i.e., foregut, midgut, hindgut) herniate out from the abdominal cavity, where they then undergo a 270º counterclockwise rotation around the superior mesenteric vessels 5. Following this rotation, the bowels return to the abdominal cavity, with fixation of the duodenojejunal loop to the left of the midline and the cecum in the right lower quadrant.

Intestinal malrotation, also known as intestinal nonrotation or incomplete rotation, refers to any variation in this rotation and fixation of the gastrointestinal tract during development. Interruption of typical intestinal rotation and fixation during fetal development can occur at a wide range of locations; this leads to various acute and chronic presentations of disease. The intestines may bend the wrong way. Or, parts of the intestine may end up in the wrong part of the abdomen. Bands of tissue called Ladd bands can grow between the intestines and body wall. These secure the intestines in the wrong place. Ladd bands can also block part of the intestine, causing digestive problems. The most common type found in pediatric patients is incomplete rotation predisposing to midgut volvulus, requiring emergent operative intervention 6.

Malrotation can lead to these complications:

- In a condition called volvulus, the bowel twists on itself, cutting off the blood flow to the tissue and causing the tissue to die. Symptoms of volvulus, including pain and cramping, are often what lead to the diagnosis of malrotation.

- Bands of tissue called Ladd’s bands may form, obstructing the first part of the small intestine (the duodenum).

- Obstruction caused by volvulus or Ladd’s bands is a potentially life-threatening problem. The bowel can stop working and intestinal tissue can die from lack of blood supply if an obstruction isn’t recognized and treated. Volvulus, especially, is a medical emergency, with the entire small intestine in jeopardy.

If you suspect any kind of intestinal obstruction because your child has bilious (yellow or green) vomiting, a swollen abdomen, or bloody stools, see your doctor immediately, and take your child to the emergency room right away.

- If the child has only intestinal malrotation, surgery is done. During surgery, any Ladd bands present are cut. The intestines are then moved to where they will be least likely to twist. If the child still has his or her appendix, it will be removed during the surgery.

- If the child has intestinal malrotation with a volvulus, surgery is done right away. The intestine is carefully untwisted. If a portion of intestine has died due to lack of blood flow, this portion must be removed. The healthy ends of the intestine are then reattached. If a long length of intestine is removed, a small opening (stoma) may need to be made in the child’s abdomen. This provides a new way for waste to leave the body. If your child needs a stoma, the doctor will tell you more.

Intestinal malrotation causes

Intestinal malrotation occurs due to disruption of the normal embryologic development of the bowel. The intestines are the longest part of the digestive system. If stretched out to their full length, they would measure more than 20 feet long by adulthood, but because they’re folded up, they fit into the relatively small space inside the abdomen.

When a fetus develops in the womb, the intestines start out as a small, straight tube between the stomach and the rectum. As this tube develops into separate organs, the intestines move into the umbilical cord, which supplies nutrients to the developing embryo.

Near the end of the first trimester of pregnancy, the intestines move from the umbilical cord into the abdomen. If they don’t properly turn after moving into the abdomen, malrotation occurs. It happens in 1 out of every 500 births in the United States and the exact cause is unknown.

Some children with intestinal malrotation are born with other associated conditions, including:

- other defects of the digestive system

- heart defects

- abnormalities of other organs, including the spleen or liver

Intestinal malrotation symptoms

An intestinal blockage can prevent the proper passage of food. So one of the earliest signs of malrotation and volvulus is abdominal pain and cramping, which happen when the bowel can’t push food past the blockage.

A baby with cramping might:

- pull up the legs and cry

- stop crying suddenly

- behave normally for 15 to 30 minutes

- repeat this behavior when the next cramp happens

Infants also may be fussy, lethargic, or have trouble pooping.

Vomiting is another symptom of malrotation, and it can help the doctor determine where the obstruction is. Vomiting that happens soon after the baby starts to cry often means the blockage is in the small intestine; delayed vomiting usually means it’s in the large intestine. The vomit may contain bile (which is yellow or green) or may resemble feces.

Other symptoms of malrotation and volvulus can include:

- a swollen abdomen that’s tender to the touch

- diarrhea and/or bloody poop (or sometimes no poop at all)

- fussiness or crying in pain, with nothing seeming to help

- rapid heart rate and breathing

- little or no pee because of fluid loss

- fever

Intestinal malrotation diagnosis

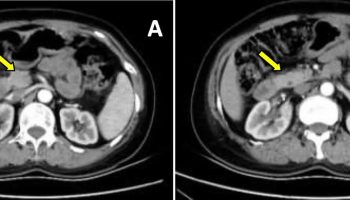

If volvulus or another intestinal blockage is suspected, the doctor will examine your child and then may order X-rays, a computed tomography (CT) scan, or an abdominal ultrasound.

The doctor may use barium or another liquid contrast agent to see the X-ray or scan more clearly. The contrast can show if the bowel has a malformation and can usually find where the blockage is.

Adults and older kids usually drink barium in a liquid form. Infants may need to be given barium through a tube inserted from the nose into the stomach, or sometimes are given a barium enema, in which the liquid barium is inserted through the rectum.

Intestinal malrotation tests may include:

- Blood tests. Tests to check electrolytes.

- Stool guaiac. A test to detect blood in stool samples.

- Computed tomography scan (CT or CAT scan). A diagnostic imaging procedure using a combination of X-rays and computer technology to produce horizontal, or axial, images (often called slices) of the body. A CT scan shows detailed images of any part of the body, including the bones, muscles, fat, and organs. CT scans are more detailed than general X-rays.

- Abdominal X-ray. A diagnostic test which may show intestinal obstructions.

- Barium swallow/upper GI test. A procedure done to examine the intestine for abnormalities. A fluid called barium (a metallic, chemical, chalky, liquid used to coat the inside of organs so that they will show up on an X-ray) is swallowed. An X-ray of the abdomen may show an abnormal location for the small intestine, obstructions (blockages), and other problems. The upper GI series generally looks at the small intestine while the lower GI series looks at the large intestine.

- Barium enema. A procedure done to examine the intestine for abnormalities. A fluid called barium (a metallic, chemical, chalky, liquid used to coat the inside of organs so that they will show up on an X-ray) is given into the rectum as an enema. An X-ray of the abdomen may show that the large intestine is not in the normal location.

- Flexible sigmoidoscopy. This test, usually only done for volvulus, looks at the lower part of the GI tract, rectum, and colon. It can be used to diagnose the volvulus.

Intestinal malrotation treatment

Treating significant malrotation almost always requires surgery. The timing and urgency will depend on the child’s condition. If there is already a volvulus, surgery must be done right away to prevent damage to the bowel.

Any child with bowel obstruction will need to be hospitalized. A tube called a nasogastric (NG) tube is usually inserted through the nose and down into the stomach to remove the contents of the stomach and upper intestines. This keeps fluid and gas from building up in the abdomen. The child may also be given intravenous (IV) fluids to help prevent dehydration and antibiotics to prevent infection.

During the surgery, which is called a Ladd procedure, the intestine is straightened out, the Ladd’s bands are divided, the small intestine is folded into the right side of the abdomen, and the colon is placed on the left side.

Because the appendix is usually found on the left side of the abdomen when there is malrotation (normally, the appendix is found on the right), it is removed. Otherwise, should the child ever develop appendicitis, it could complicate diagnosis and treatment.

If it appears that blood may still not be flowing properly to the intestines, the doctor may do a second surgery within 48 hours of the first. If the bowel still looks unhealthy at this time, the damaged portion might be removed.

If the child is seriously ill at the time of surgery, an ileostomy or colostomy usually will be done. In this procedure, the diseased bowel is completely removed, and the end of the normal, healthy intestine is brought out through an opening on the skin of the abdomen (called a stoma). Fecal matter (poop) passes through this opening and into a bag that is taped or attached with adhesive to the child’s belly.

In young children, depending on how much bowel was removed, the ileostomy or colostomy is often a temporary condition that can later be reversed with another operation.

Most of these surgeries are successful, although some kids have recurring problems after surgery. Recurrent volvulus is rare, but a second bowel obstruction due to adhesions (scar tissue build-up after any type of abdominal surgery) could happen later.

Children who had a large portion of the small intestine removed can have too little bowel to maintain adequate nutrition (a condition known as short bowel syndrome). They might need intravenous (IV) nutrition for a time after surgery (or even permanently if too little intestine remains) and may require a special diet afterward.

Most kids in whom the volvulus and malrotation are found and treated early, before permanent injury to the bowel happens, do well and develop normally.

Long-term management of growth and nutrition

Patients with short-bowel syndrome are at high risk for failure to thrive. These infants require frequent monitoring of growth parameters during the immediate postoperative period to ensure adequate weight, length, and head circumference gains.

Patients may develop iron, folate, and vitamin B-12 deficiencies due to malabsorption depending on how much bowel is removed.

Outpatient care should be individualized, depending on each patient’s operative and postoperative course.

Development considerations

Children with prolonged hospitalization may experience developmental delays and require aggressive physical, occupational, and speech therapy.

Infants can develop poor truncal control due to prolonged periods in the supine position while hospitalized, additionally they may develop contractures in the extremities, or feeding aversion due to prolonged periods with nasogastric tubes in place and taking nothing by mouth.

Developmental delays should be monitored in both inpatient and outpatient settings and should be intervened upon as early as possible 7.

Intestinal malrotation complications

Complications include the following:

Short-bowel syndrome

Short-bowel syndrome is the most common complication of midgut volvulus. These patients have longer delays to recovery of bowel motility and function. They are at high risk for malabsorption and can require long-term parenteral nutrition. Furthermore, these patients have more complications from treatment and longer hospital stays than patients with malrotation without volvulus.

Infection

Wound infections and sepsis can occur in the immediate postoperative period, requiring extended treatment with intravenous antibiotics. Additionally, central venous catheters have the potential to become infected causing bacteremia and/or sepsis

Surgical complications

Postoperative and surgical complications are more likely to occur in those patients with acute symptoms than those with chronic symptoms 8. One review reported an overall complication rate of 8.7% (14 of 161) following Ladd procedure 9. Complications reported include adhesive small bowel obstruction in 6% with 5 requiring reoperation (3%), and 1 patient developed recurrent volvulus (1%). A second review showed comparable rates of recurrent volvulus (2%, 1 of 57) and reoperation for adhesive small bowel obstruction (2%, 1 of 57) 10. Other series have reported lower rates of recurrent volvulus, 0.4% in one series of 441 patients, and 0.6% in a series of 159 patients who underwent Ladd’s procedure 11.

Persistent gastrointestinal symptoms

In the same series of 57 patients, 13 had persistent (>6 months) gastrointestinal symptoms, including constipation (6), intractable diarrhea (1), abdominal pain (2), vomiting (3), and feeding difficulties (1) following Ladd procedure 10.

Mortality

Death occurs due to peritonitis, late nutritional complications, or catheter-related sepsis. Rates are increased among children younger than one year. Following Ladd procedure, mortality rates reported in the literature are as low as 2% 9. However, if more than 75% of the bowel is necrotic, mortality is as high as 65% 11.

Intestinal malrotation prognosis

Prognosis is dependent on the presence of ischemic or necrotic bowel, the amount of bowel removed, and the age of the child. In general, older children have improved morbidity and mortality compared to infants. The presence of midgut volvulus is associated with prolonged hospital length of stay. Long-term prognosis is dependent on how much bowel is removed and the development of short-bowel syndrome.

References- Dilley AV, Pereira J, Shi EC, Adams S, Kern IB, Currie B. The radiologist says malrotation: does the surgeon operate?. Pediatr Surg Int. 2000. 16(1-2):45-9.

- Berseth CL. Disorders of the intestines and pancreas. Taeusch WH, Ballard RA, eds. Avery’s Diseases of the Newborn. 7th ed. Philadelphia: WB Saunders; 1998. 918.

- Varetti C, Meucci D, Severi F, Di Maggio G, Bocchi C, Petraglia F, et al. Intrauterine volvulus with malrotation: prenatal diagnosis. Minerva Pediatr. 2013 Apr. 65(2):219-23.

- Smith EI. Malrotation of the intestine. Welch KJ, Randolph JG, Ravitch MN, eds. Pediatric Surgery. 4th ed. St. Louis: MO: Mosby-Year Book; 1986. Vol 2: 882-95.

- Intestinal malrotation. https://emedicine.medscape.com/article/930313-overview

- Lee HC, Pickard SS, Sridhar S, Dutta S. Intestinal malrotation and catastrophic volvulus in infancy. J Emerg Med. 2012 Jul. 43(1):e49-51.

- Elsinga RM, Roze E, Van Braeckel KN, Hulscher JB, Bos AF. Motor and cognitive outcome at school age of children with surgically treated intestinal obstructions in the neonatal period. Early Hum Dev. 2013 Mar. 89(3):181-5.

- Wallberg SV, Qvist N. Increased risk of complication in acute onset intestinal malrotation. Dan Med J. 2013. 60:A4744.

- El-Gohary Y, Alagtal M, Gillick J. Long-term complications following operative intervention for intestinal malrotation: a 10-year review. Pediatr Surg Int. 2010 Feb. 26(2):203-6.

- Feitz R, Vos A. Malrotation: the postoperative period. J Pediatr Surg. 1997 Sep. 32(9):1322-4.

- Dassinger MS, Smith SD. Chapter 86. Disorders of Intestinal Rotation and Fixation. Coran A, Adzick NS, Krummel TM, et al, eds. Pediatric Surgery. 7th ed. Elsevier; 837-51.