Klatskin tumor

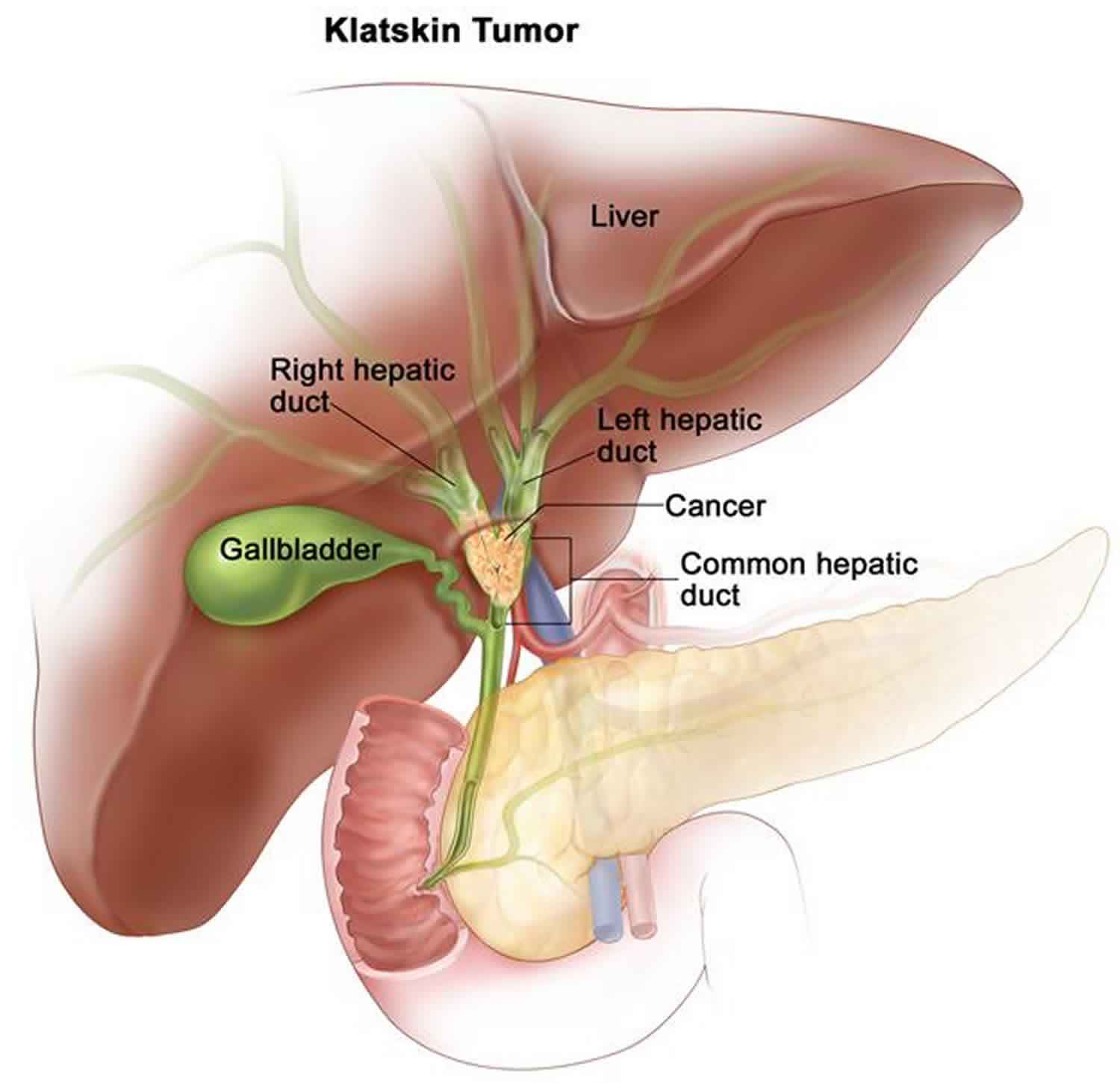

Klatskin tumor also called hilar cholangiocarcinoma or central bile duct carcinoma, is cancer that develops in cells that line the bile ducts in the liver, where the right and left common hepatic ducts meet in an area called the hilum and leave the liver. Klatskin tumor is the most common type of cholangiocarcinoma, accounting for more than half of all cases and usually presenting in the 5th to 7th decade of life and are seen slightly more frequently in males (1.3:1 male to female ratio) 1. Klatskin tumor is a term that was traditionally given to a hilar cholangiocarcinoma, occurring at the bifurcation of the common hepatic duct. Typically, these tumors are small, poorly differentiated, exhibit aggressive biologic behavior, and tend to obstruct the intrahepatic bile ducts.

Klatskin tumor is a rare type of tumor, with an annual incidence of no more than 1: 100 000 2.

Klatskin tumor symptoms usually don’t present until advanced stages of disease, when jaundice is the most common feature. Other symptoms include abdominal pain, unintentional weight loss, and a general feeling of being unwell (malaise) 3. Metastasis to regional lymph nodes is frequent. It can spread from the pericholedochal nodes in the hepatoduodenal ligament to the posteriorsuperior area around the pancreatic head, common hepatic artery and portal vein.

The cause of Klatskin tumors is unknown 1. Studies suggest that a combination of genetic, environmental, and lifestyle factors (multifactorial) likely influence whether a person will develop cholangiocarcinoma. Because Klatskin tumors are often discovered after they have spread, they can be challenging to treat effectively 4. Surgical removal of the tumor and relief of bile duct blockage are the main goals of treatment 5. Affected individuals can survive for several months to several years after diagnosis.

The only curative treatment is a complete surgical resection with histologically negative margins 6. Current surgical strategies usually include choledochectomy, extended hepatectomy, and portal resection. Due to the local anatomy, the proximal and lateral safety margin R0 resection is a surgery that demands excellent technique 7. Molina et al. 8 reported that lymph node involvement and metastasis were important prognostic factors. The median survival of inoperable patients is 6 to 12 months, and the most common causes of death are liver failure and septic complications.

Figure 1. Bile duct anatomy

Figure 2. The common bile duct is closely associated with the pancreatic duct and the duodenum

Figure 3. Klatskin tumor

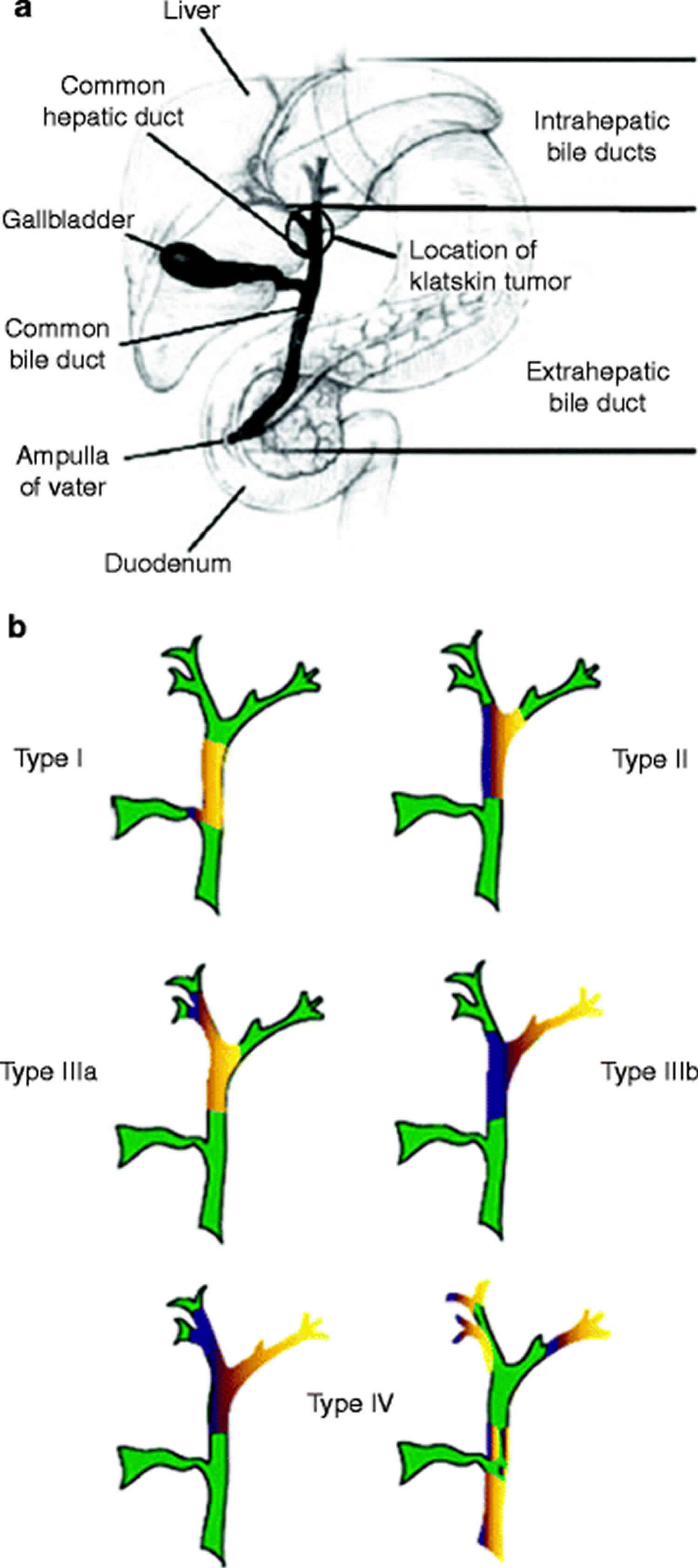

Klatskin tumor type

Determine the exact location of Klatskin tumor mass and can be used in the preoperative assessment. The Bismuth-Corlette system is one classification 9:

- type I: the lesion is limited to the common hepatic duct distal to the confluence of the right and left ducts

- type II: the tumor involves the confluence of the right and left hepatic ducts

- type III: the tumor involves one of the hepatic ducts

- type IV: the tumor invades the right and left hepatic ducts and hence it becomes unresectable

Figure 4. Klatskin tumor type

Klatskin tumor causes

The cause of Klatskin tumor is still unclear, but many risk factors have been identified. Infection seems to be closely related to the development of cholangiocarcinoma in Asian countries 6. Liver flukes, including Clonorchis trematode and Thai liver fluke, can chronically infect the bile duct and cause the development of cholangiocarcinoma 10. Other risk factors related to Klatskin tumor include alcoholism, hepatitis B and hepatitis C viruses, chronic pancreatitis, primary sclerosing cholangitis, choledochal cysts, liver fluke infection (Clonorchis sinensis and Opisthorchis viverrini) and cholelithiasis (intrahepatic bile duct stones) 11, but most Klatskin tumors are sporadic with no obvious predisposing factors 12.

Risk factors for developing Klatskin tumor

A risk factor is anything that affects your chance of getting a disease like cancer. Different cancers have different risk factors. Some risk factors, like smoking, can be changed. Others, like a person’s age or family history, can’t be changed.

But having a risk factor, or even many risk factors, does not mean that a person will get the disease. And many people who get the disease have few or no known risk factors.

Researchers have found some risk factors that make a person more likely to develop bile duct cancer.

Certain diseases of the liver or bile ducts

People who have chronic (long-standing) inflammation of the bile ducts have an increased risk of developing bile duct cancer. Certain conditions of the liver or bile ducts can cause this, these include:

- Primary sclerosing cholangitis, a condition in which inflammation of the bile ducts (cholangitis) leads to the formation of scar tissue (sclerosis). People with primary sclerosing cholangitis have an increased risk of bile duct cancer. The cause of the inflammation is not usually known. Many people with this disease also have inflammation of the large intestine, called ulcerative colitis.

- Bile duct stones, which are a lot like but much smaller than gallstones, can also cause inflammation that increases the risk of bile duct cancer.

- Choledochal cyst disease, a rare condition some people are born with. It causes bile-filled sacs along the bile ducts. (Choledochal means having to do with the common bile duct.) If not treated, the bile sitting in these sacs causes inflammation of the duct walls. The cells of the duct wall often have areas of pre-cancerous changes, which, over time, cam progress to bile duct cancer.

- Liver fluke infections, which occur in some Asian countries when people eat raw or poorly cooked fish that are infected with these tiny parasite worms. In humans, these flukes live in the bile ducts and can cause bile duct cancer. There are several types of liver flukes. The ones most closely related to bile duct cancer risk are Clonorchis sinensis and Opisthorchis viverrini. Liver fluke infection is rare in the US, but it can affect people who travel to Asia.

- Abnormalities where the bile duct and pancreatic duct normally meet which can allow digestive juices from the pancreas to reflux (flow back) into the bile ducts. This backward flow keeps the bile from moving through the bile ducts the way it should. People with these abnormalities are at higher risk of bile duct cancer.

- Cirrhosis, which is damage to the liver caused by scar tissue. It’s caused by irritants like alcohol and diseases like hepatitis. Studies have found it raises the risk of bile duct cancer.

- Infection with hepatitis B virus or hepatitis C virus which increases the risk of intrahepatic bile duct cancers. This may be at least in part because long-term infections with these viruses can also lead to cirrhosis.

Other rare diseases of the liver and bile duct that may increase the risk of developing bile duct cancer include polycystic liver disease and Caroli syndrome (a dilation of the intrahepatic bile ducts present at birth).

Inflammatory bowel disease

Inflammatory bowel disease includes ulcerative colitis and Crohn’s disease. People with these diseases have an increased risk of bile duct cancer.

Older age

Older people are more likely than younger people to get bile duct cancer. Most people diagnosed with bile duct cancer are in their 60s or 70s.

Ethnicity and geography

In the US, the risk of bile duct cancer is highest among Hispanic Americans. Worldwide, bile duct cancer is much more common in Southeast Asia and China, largely because of the high rate of infection with liver flukes in these areas.

Obesity

Being overweight or obese can increase the risk of cancers of the gallbladder and bile ducts. This could be because obesity increases the risk of gallstones and bile duct stones, as well as the risk of non-alcoholic fatty liver disease. But there may be other ways that being overweight can lead to bile duct cancers, such as changes in certain hormones.

Non-alcoholic fatty liver disease

Non-alcoholic fatty liver disease is the build-up of extra fat in the liver cells that’s not caused by alcohol. Over time, this can cause swelling and scarring that can progress to cancer.

Exposure to Thorotrast

A radioactive substance called Thorotrast (thorium dioxide) was used as a contrast agent for x-rays until the 1950s. It was found to increase the risk for bile duct cancer, as well as some types of liver cancer, and is no longer used.

Family history

A history of bile duct cancer in the family seems to increase a person’s chances of developing this cancer, but the risk is still low because this is a rare disease. Most bile duct cancers are not found in people with a family history of the disease.

Diabetes

People with diabetes (type 1 or type 2) have a higher risk of bile duct cancer. This increase in risk is not high, and the overall risk of bile duct cancer in someone with diabetes is still low.

Alcohol

People who drink alcohol are more likely to get intrahepatic bile duct cancer. The risk is higher in those who have liver problems from drinking alcohol.

Other possible risk factors

Studies have found other factors that might increase the risk of bile duct cancer, but the links are not as clear. These include:

- Smoking

- Chronic pancreatitis (long-term inflammation of the pancreas)

- Infection with HIV (the virus that causes AIDS)

- Exposure to asbestos

- Exposure to radon or other radioactive chemicals

- Exposure to dioxin, nitrosamines, or polychlorinated biphenyls (PCBs)

Klatskin tumor symptoms

The symptoms associated with Klatskin tumors are usually due to blocked bile ducts. Symptoms may include 1:

- Jaundice: Jaundice is the most common symptom of bile duct cancer, but most of the time, jaundice isn’t caused by cancer. It’s more often caused by hepatitis (inflammation of the liver) or a gallstone that has traveled to the bile duct. But whenever jaundice occurs, a doctor should be seen right away.

- Itching: Excess bilirubin in the skin can also cause itching. Most people with bile duct cancer notice itching.

- Light colored stools: Bilirubin contributes to the brown color of bowel movements, so if it doesn’t reach the intestines, the color of a person’s stool might be lighter. If the cancer blocks the release of bile and pancreatic juices into the intestine, a person might not be able to digest fatty foods. The undigested fat can also cause stools to be unusually pale. They might also be bulky, greasy, and float in the toilet.

- Dark urine: When bilirubin levels in the blood get high, it can also come out in the urine and turn it dark.

- Abdominal pain: Early bile duct cancers seldom cause pain, but bigger tumors may cause belly pain, especially below the ribs on the right side.

- Loss of appetite / weight loss: People with bile duct cancer may not feel hungry and may lose weight without trying to do so.

- Fever: Some people with bile duct cancer develop fevers.

- Nausea / vomiting: These are not common symptoms of bile duct cancer, but they may occur in people who develop an infection (cholangitis) as a result of bile duct blockage. These symptoms are often seen along with a fever.

The symptoms are usually fatigue, jaundice, and cachexia, indicating metastatic or advanced tumors. Most patients have biliary symptoms, including painless jaundice. About 10% of patients also simultaneously present with cholangitis 13.

What symptoms are common in patients with non-resectable Klatskin tumors?

Two of the most common features noted in patients with non-resectable Klatskin tumors are bile duct blockage (which can lead to jaundice, itching, and other symptoms) and pain 1.

Klatskin tumor diagnosis

Most bile duct cancers aren’t found until a person goes to a doctor because they have symptoms.

Medical history and physical exam

If there’s reason to suspect that you might have bile duct cancer, your doctor will want to take your complete medical history to check for risk factors and to learn more about your symptoms.

A physical exam is done to look for signs of bile duct cancer or other health problems. If bile duct cancer is suspected, the exam will focus mostly on the abdomen (belly) to check for any lumps, tenderness, or build-up of fluid. The skin and the white part of the eyes will be checked for jaundice (a yellowish color).

If symptoms and/or the results of the physical exam suggest you might have bile duct cancer, tests will be done. These could include lab tests, imaging tests, and other procedures.

Blood tests

Tests of liver and gallbladder function

Lab tests might be done to find out how much bilirubin is in your blood. Bilirubin is the chemical that causes jaundice. Problems in the bile ducts, gallbladder, or liver can raise the blood level of bilirubin.

The doctor may also do tests for albumin, liver enzymes (alkaline phosphatase, AST, ALT, and GGT), and certain other substances in your blood. These may be called liver function tests. They can help diagnose bile duct, gallbladder, or liver disease. If levels of these substances are higher, it might point to blockage of the bile duct, but they can’t show if it’s due to cancer or some other reason.

Tumor markers

Tumor markers are substances made by cancer cells that can sometimes be found in the blood. People with bile duct cancer may have high blood levels of the markers called CEA and CA 19-9. High levels of these markers often mean that cancer is present, but the high levels can also be caused by other types of cancer, or even by problems other than cancer. Also, not all bile duct cancers make these tumor markers, so low or normal levels don’t always mean cancer is not present.

Still, these tests can sometimes be useful after a person is diagnosed with bile duct cancer. If the levels of these markers are found to be high, they can be followed over time to help see how well treatment is working.

Imaging tests

Imaging tests use x-rays, magnetic fields, or sound waves to create pictures of the inside of your body. Imaging tests can be done for a number of reasons, including:

- To look for suspicious areas that might be cancer

- To help a doctor guide a biopsy needle into a suspicious area to take a sample for testing

- To learn how far cancer has spread

- To help make treatment decisions

- To help find out if treatment is working

- To look for signs of the cancer coming back after treatment

Imaging tests can often show a bile duct blockage. But they often can’t show if the blockage is caused by a tumor or a less serious problem like scarring.

People who have (or might have) bile duct cancer may have one or more of these tests:

Ultrasound

Ultrasound uses sound waves and their echoes to create images of the inside of the body. A small instrument called a transducer gives off sound waves and picks up the echoes as they bounce off organs inside the body. The echoes are converted by a computer into an image on a screen.

- Abdominal ultrasound: This is often the first imaging test done in people who have symptoms such as jaundice or pain in the right upper part of their abdomen (belly). This is an easy test to have and it doesn’t use radiation. You simply lie on a table while a technician moves the transducer on the skin over your abdomen. This type of ultrasound can also be used to guide a needle into a suspicious area or lymph node so that cells can be removed (biopsied) and looked at under a microscope. This is called an ultrasound-guided needle biopsy.

- Endoscopic or laparoscopic ultrasound: In these techniques, the doctor puts the ultrasound transducer inside your body and closer to the bile duct. This gives more detailed images than a standard ultrasound. The transducer is on the end of a thin, lighted tube that has a camera on it. The tube is either passed through your mouth, down through your stomach, and into the small intestine near the bile ducts (endoscopic ultrasound) or through a small surgical cut in the skin on side of your body (laparoscopic ultrasound). If there’s a tumor, the doctor might be able to see how far it has grown and spread, which can help in planning for surgery. Ultrasound may be able to show if nearby lymph nodes are enlarged, which can be a sign that cancer has reached them. Needle biopsies of suspicious areas might be done.

Computed tomography (CT) scan

A CT scan uses x-rays to make detailed cross-sectional images of your body. It can be used to

- Help diagnose bile duct cancer by showing tumors in the area.

- Help stage the cancer (find out how far it has spread). CT scans can show the organs near the bile duct (especially the liver), as well as lymph nodes and distant organs where cancer might have spread to.

- A type of CT known as CT angiography can be used to look at the blood vessels around the bile ducts. This can help determine if surgery is an option.

- Guide a biopsy needle into a suspected tumor. This is called a CT-guided needle biopsy. To do it, you stay on the CT scanning table while the doctor advances a biopsy needle through your skin and toward the mass. CT scans are repeated until the needle is inside the mass. A small amount of tissue (a sample) is then taken out through the needle.

Magnetic resonance imaging (MRI) scan

Like CT scans, MRI scans show detailed images of soft tissues in the body. But MRI scans use radio waves and strong magnets instead of x-rays. A contrast material called gadolinium may be injected into a vein before the scan to see details better.

MRI scans can provide a great deal of detail and be very helpful in looking at the bile ducts and other organs. Sometimes they can help tell a benign (non-cancer) tumor from one that’s cancer. Special types of MRI scans may also be used in people who may have bile duct cancer:

- MR cholangiopancreatography (MRCP) can be used to look at the bile ducts and is described below in the section on cholangiography.

- MR angiography (MRA) looks at blood vessels and is also covered in the section on angiography.

Cholangiography

A cholangiogram is an imaging test that looks at the bile ducts to see if they’re blocked, narrowed, or dilated (widened). This can help show if someone might have a tumor that’s blocking a duct. It can also be used to help plan surgery. There are several types of cholangiograms, each of which has different pros and cons.

- Magnetic resonance cholangiopancreatography (MRCP): This is a way to get images of the bile ducts with the same type of machine used for standard MRIs. Neither an endoscope or an IV contrast agent is used, unlike the other types of cholangiograms. Because it’s non-invasive (nothing is put in your body), doctors often use MRCP if they just need images of the bile ducts. This test can’t be used to get biopsy samples of tumors or to place stents (small tubes) in the ducts to keep them open.

- Endoscopic retrograde cholangiopancreatography (ERCP): In this procedure, a doctor passes a long, flexible tube (endoscope) down your throat, through your stomach, and into the first part of the small intestine. This is usually done while you are sedated (given medicine to make you sleepy). A small catheter (tube) is passed out of the end of the endoscope and into the common bile duct. A small amount of contrast dye is injected through the catheter. The dye helps outline the bile ducts and pancreatic duct as x-rays are taken. The images can show narrowing or blockage of these ducts. This test is more invasive than MRCP, but it has the advantage of allowing the doctor to take samples of cells or fluid for testing. ERCP can also be used to put a stent (a small tube) into a duct to help keep it open.

- Percutaneous transhepatic cholangiography (PTC): To do this procedure, the doctor puts a thin, hollow needle through the skin of your belly and into a bile duct inside your liver. You’re given medicines through an IV line to make you sleepy before this test. A local anesthetic is also used to numb the area before putting in the needle. A contrast dye is then injected through the needle, and x-rays are taken as it passes through the bile ducts. Like ERCP, this test can also be used to take samples of fluid or tissues or to put a stent (small tube) in the bile duct to help keep it open. Because it’s more invasive, PTC is not usually used unless ERCP has already been tried or can’t be done for some reason.

Angiography

Angiography or an angiogram is an x-ray test for looking at blood vessels in and around the liver and bile ducts. A thin plastic tube called a catheter is threaded into an artery and a small amount of contrast dye is injected to outline blood vessels. Then x-rays are taken. The images show if blood flow in is blocked anywhere or affected by a tumor, as well as any abnormal blood vessels in the area. The test can also show if a bile duct cancer has grown through the walls of blood vessels. This information is mainly used to help surgeons decide whether a cancer can be removed and to help plan the operation.

Angiography can also be done with a CT scan (CT angiography) or an MRI (MR angiography). These tend to be used more often because they give information about the blood vessels without the need for a catheter. You may still need an IV line so that a contrast dye can be injected into your bloodstream during the imaging.

Other tests

Doctors may also use special instruments (endoscopes) to go into the body to get a more direct look at the bile duct and nearby areas. The scopes may be passed through small surgical incisions (cuts) or through natural body openings like the mouth.

Laparoscopy

Laparoscopy is a type of surgery. The doctor puts a thin tube with a light and a small video camera on the end (a laparoscope) through a small incision (cut) in the front of your belly to look at the bile ducts, gallbladder, liver, and other nearby organs and tissues. (Sometimes more than one cut is made.) This is typically done in the operating room while drugs are used to put you into a deep sleep and not feel pain (general anesthesia) during the surgery.

Laparoscopy can help doctors plan surgery or other treatments, and can help determine the stage (extent) of the cancer. If needed, doctors can also use special instruments put in through the incisions to take out biopsy samples for testing. Laparoscopy is often done before surgery to remove the cancer, to help make sure the tumor can be removed completely.

Cholangioscopy

This procedure can be done during an endoscopic retrograde cholangiopancreatography (ERCP). The doctor passes a very thin fiber-optic tube with a tiny camera on the end down through the larger tube used for the ERCP. From there it can be maneuvered into the bile ducts. This lets the doctor see any blockages, stones, or tumors and even biopsy them.

Biopsy

Imaging tests might suggest that a bile duct cancer is present, but in many cases samples of bile duct cells or tissue is removed (biopsied) and looked at with a microscope to be sure of the diagnosis.

But a biopsy isn’t always be done before surgery for a possible bile duct cancer. If imaging tests show a tumor in the bile duct, the doctor may decide to proceed directly to surgery and to treat the tumor as a bile duct cancer.

Types of biopsies

There are many ways to take biopsy samples to diagnose bile duct cancer.

- During cholangiography: If ERCP or PTC is being done, a sample of bile may be collected during the procedure to look for cancer cells in the fluid. Bile duct cells and tiny pieces of bile duct tissue can also be taken out by biliary brushing. Instead of injecting contrast dye and taking x-ray pictures (as for ERCP or PTC), the doctor advances a small brush with a long, flexible handle through the endoscope or needle. The end of the brush is used to scrape cells and small tissue fragments from the lining of the bile duct. These are then looked at with a microscope.

- During cholangioscopy: Biopsy specimens can also be taken during cholangioscopy. This test lets the doctor see the inside surface of the bile duct and take samples of suspicious areas.

- Needle biopsy: For this test, a thin, hollow needle is put through the skin and into the tumor without making a cut in the skin. (The skin is numbed first with a local anesthetic.) The needle is usually guided into place using ultrasound or CT scans. When the images show that the needle is in the tumor, cells and/or fluid are drawn into the needle and sent to the lab to be tested.

In most cases, this is done as a fine needle aspiration (FNA) biopsy, which uses a very thin needle attached to a syringe to suck out (aspirate) a sample of cells. Sometimes, the FNA doesn’t get enough cells for a definite diagnosis, so a core needle biopsy, which uses a slightly larger needle to get a bigger sample, may be done.

Klatskin tumor staging

After a person is diagnosed with Klatskin tumor or hilar bile duct cancer, doctors will try to figure out if it has spread, and if so, how far. This process is called staging. The stage of a cancer describes how much cancer is in the body. It helps determine how serious the cancer is and how best to treat it. Doctors also use a cancer’s stage when talking about survival statistics.

The earliest stage Klatskin tumor or hilar bile duct cancers are stage 0, also called carcinoma in situ (CIS) or high-grade biliary intraepithelial neoplasia. Stages then range from stages I (1) through IV (4). As a rule, the lower the number, the less the cancer has spread. A higher number, such as stage 4, means cancer has spread more. And within a stage, an earlier letter means a lower stage.

Although each person’s cancer experience is unique, cancers with similar stages tend to have a similar outlook and are often treated in much the same way.

The staging system most often used for Klatskin tumor or hilar bile duct cancer is the American Joint Committee on Cancer (AJCC) TNM system, which is based on 3 key pieces of information:

- The extent (size) of the main tumor (T): Has the cancer grown through the bile duct or reached nearby structures or organs?

- The spread to nearby lymph nodes (N): Has the cancer spread to nearby lymph nodes?

- The spread (metastasis) to distant sites (M): Has the cancer spread to distant lymph nodes or distant organs such as the bones, lungs, or peritoneum (the lining of the abdomen [belly])?

The system described below is the most recent AJCC system, effective January 2018. It’s used only for perihilar bile duct cancers (those starting in the hilum, just outside the liver).

Numbers or letters after T, N, and M provide more details about each of these factors. Higher numbers mean the cancer is more advanced.

Once a person’s T, N, and M categories have been determined, this information is combined in a process called stage grouping to assign an overall stage.

Perihilar bile duct cancer is typically given a clinical stage based on the results of a physical exam, biopsy, and imaging tests. If surgery is done, the pathologic stage also called the surgical stage, is determined by examining the tissue removed during the operation.

Cancer staging can be complex, so ask your doctor to explain it to you in a way you understand.

Table 1. Stages of perihilar bile duct cancer

| AJCC Stage | Stage grouping | Stage description* |

| 0 | Tis N0 M0 | The cancer is only in the mucosa (the innermost layer of cells in the bile duct). It hasn’t started growing into the deeper layers (Tis). It has not spread to nearby lymph nodes (N0) or to distant sites (M0). |

| I | T1 N0 M0 | The cancer has grown into deeper layers of the bile duct wall, such as the muscle layer or fibrous tissue layer (T1). It has not spread to nearby lymph nodes (N0) or to distant sites (M0). |

| II | T2a or T2b N0 M0 | The tumor has grown through the bile duct wall and into the nearby fatty tissue (T2a) or into the nearby liver tissue (T2b). The cancer has not spread to nearby lymph nodes (N0) or to distant sites (M0). |

| IIIA | T3 N0 M0 | The cancer is growing into branches of the main blood vessels of the liver (the portal vein and/or the hepatic artery) on one side (left or right) (T3). The cancer has not spread to nearby lymph nodes (N0) or to distant sites (M0). |

| IIIB

| T4 N0 M0 | The cancer is growing into the main blood vessels of the liver (the portal vein and/or the common hepatic artery) or into branches of these vessels on both sides (left and right), OR the cancer is growing into other bile ducts on one side (left or right) and a main blood vessel on the other side (T4). The cancer has not spread to nearby lymph nodes (N0) or to distant sites (M0). |

| IIIC | Any T N1 M0 | The cancer is any size and may or may not be growing outside the bile duct or into nearby blood vessels (Any T) and has spread to 1 to 3 nearby lymph nodes (N1). It has not spread to distant sites (M0). |

| IVA | Any T N2 M0 | The cancer is any size and may or may not be growing outside the bile duct or into nearby blood vessels (Any T). It has also spread to 4 or more nearby lymph nodes (N2). It has not spread to distant sites (M0). |

| IVB | Any T Any N M1 | The cancer is any size and may or may not be growing outside the bile duct or into nearby blood vessels (Any T). It may or may not have spread to nearby lymph nodes (Any N). It has spread to distant organs such as the bones, lungs, or distant parts of the liver (M1). |

Footnotes:

*The T categories are described in the table above, except for:

- TX: Main tumor cannot be assessed due to lack of information.

- T0: No sign of a primary tumor.

The N categories are described in the table above, except for:

- NX: Nearby lymph nodes cannot be assessed due to lack of information.

Klatskin tumor treatment

Different types of treatments are available for patients with Klatskin tumor. Some treatments are standard (the currently used treatment), and some are being tested in clinical trials.

The main types of treatment for bile duct cancer include:

- Surgery

- Radiation Therapy

- Chemotherapy

- Targeted Therapy Drugs

- Immunotherapy

- Palliative Therapy

For patients whose tumors are operable, the current primary treatment is surgery. Several studies have shown that patients undergoing resection have significantly longer survival than in non-surgical patients, and the overall 5-year survival rate for highly selected patients is close to 53% 6.

Resectable Klatskin tumor

Treatment of resectable perihilar bile duct cancer may include the following:

- Surgery to remove the cancer, which may include partial hepatectomy.

- Stent placement or percutaneous transhepatic biliary drainage as palliative therapy, to relieve jaundice and other symptoms and improve the quality of life.

- Surgery followed by radiation therapy and/or chemotherapy.

The resection for Klatskin tumor involves achieving an R0 surgical margin and then trying to improve the survival time. A number of studies have shown that, compared with R1 resection, the overall survival rate of the R0 surgical margin increased significantly 15.

There are also some other surgical factors and tumor features related to longer survival time after surgery. Studies showed that the presence of lymph node metastasis was associated with poor survival 16. Some case analyses showed that elevated preoperative serum bilirubin, histological tumor type, and tumor differentiation in patients are associated with lower survival rates, although these findings vary from study to study 17. In an analysis, older age, higher M stages, and higher pathology grades were related to the worse prognosis.

Unresectable, Recurrent, or Metastatic Klatskin tumor

Current unresectable disease criteria include major portal vein involvement or encapsulation, bilateral spread, bilateral hepatic artery involvement, unilateral liver arterial involvement, and the presence of distant lymph nodes or organ metastases 18.

Treatment of unresectable, recurrent, or metastatic perihilar bile duct cancer may include the following:

- Stent placement or biliary bypass as palliative treatment to relieve symptoms and improve the quality of life.

- External or internal radiation therapy as palliative treatment to relieve symptoms and improve the quality of life.

- Chemotherapy.

- A clinical trial of external radiation therapy combined with hyperthermia therapy, radiosensitizer drugs, or chemotherapy.

- A clinical trial of chemotherapy and radiation therapy followed by a liver transplant.

Klatskin tumor surgery

The following types of surgery are used to treat bile duct cancer:

- Removal of the bile duct: A surgical procedure to remove part of the bile duct if the tumor is small and in the bile duct only. Lymph nodes are removed and tissue from the lymph nodes is viewed under a microscope to see if there is cancer.

- Partial hepatectomy: A surgical procedure in which the part of the liver where cancer is found is removed. The part removed may be a wedge of tissue, an entire lobe, or a larger part of the liver, along with some normal tissue around it.

- Whipple procedure: A surgical procedure in which the head of the pancreas, the gallbladder, part of the stomach, part of the small intestine, and the bile duct are removed. Enough of the pancreas is left to make digestive juices and insulin.

After the doctor removes all the cancer that can be seen at the time of the surgery, some patients may be given chemotherapy or radiation therapy after surgery to kill any cancer cells that are left. Treatment given after the surgery, to lower the risk that the cancer will come back, is called adjuvant therapy. It is not yet known whether chemotherapy or radiation therapy given after surgery helps keep the cancer from coming back.

The following types of palliative surgery may be done to relieve symptoms caused by a blocked bile duct and improve quality of life:

- Biliary bypass: If cancer is blocking the bile duct and bile is building up in the gallbladder, a biliary bypass may be done. During this operation, the doctor will cut the gallbladder or bile duct in the area before the blockage and sew it to the part of the bile duct that is past the blockage or to the small intestine to create a new pathway around the blocked area.

- Endoscopic stent placement: If the tumor is blocking the bile duct, surgery may be done to put in a stent (a thin tube) to drain bile that has built up in the area. The doctor may place the stent through a catheter that drains the bile into a bag on the outside of the body or the stent may go around the blocked area and drain the bile into the small intestine.

- Percutaneous transhepatic biliary drainage: A procedure used to x-ray the liver and bile ducts. A thin needle is inserted through the skin below the ribs and into the liver. Dye is injected into the liver or bile ducts and an x-ray is taken. If the bile duct is blocked, a thin, flexible tube called a stent may be left in the liver to drain bile into the small intestine or a collection bag outside the body.

Klatskin tumor prognosis

Most Klatskin tumors are diagnosed at an advanced stage 5. The best long-term results are achieved with surgical intervention 3. The median survival of patients with non-resectable Klatskin tumors after palliative drainage is two to eight months 1. Complications include recurring bacterial cholangitis and/or liver failure (cirrhosis) 4. The aim of palliative treatment is improvement in the patient’s quality of life. This includes treating cholestasis and cholangitis, which secondarily prolongs survival 19.

Table 2. 5-year relative survival rates for extrahepatic bile duct cancers (those starting outside the liver). This includes both perihilar and distal bile duct cancers.

| Surveillance, Epidemiology, and End Results (SEER) stage | 5-year relative survival rate |

| Localized | 15% |

| Regional | 16%* |

| Distant | 2% |

| All SEER stages combined | 10% |

Footnotes: Keep in mind that survival rates are estimates and are often based on previous outcomes of large numbers of people who had a specific cancer, but they can’t predict what will happen in any particular person’s case. These statistics can be confusing and may lead you to have more questions. Talk with your doctor about how these numbers may apply to you, as he or she is familiar with your situation.

*The 5-year survival for these tumors at the regional stage is slightly better than for the localized stage, although the reason for this is not exactly clear.

Understanding the numbers:

- These numbers apply only to the stage of the cancer when it is first diagnosed. They do not apply later on if the cancer grows, spreads, or comes back after treatment.

- These numbers don’t take everything into account. Survival rates are grouped based on how far the cancer has spread. But other factors, such as your age and overall health, and how well the cancer responds to treatment, can also affect your outlook.

- People now being diagnosed with bile duct cancer may have a better outlook than these numbers show. Treatments improve over time, and these numbers are based on people who were diagnosed and treated at least five years earlier.

- Cholangiocarcinoma. https://emedicine.medscape.com/article/277393-overview

- Seehofer D, Kamphues C, Neuhaus P. Resection of Klatskin tumors. Chirurg. 2012;83(3):221–28.

- Klatskin tumor. https://www.orpha.net/consor/cgi-bin/OC_Exp.php?lng=en&Expert=99978

- Cholangiocarcinoma. https://ghr.nlm.nih.gov/condition/cholangiocarcinoma

- Bile Duct Cancer. https://www.cancer.org/cancer/bile-duct-cancer.html

- Zhang X, Liu H. Klatskin Tumor: A Population-Based Study of Incidence and Survival. Med Sci Monit. 2019;25:4503–4512. Published 2019 Jun 17. doi:10.12659/MSM.914987 https://www.ncbi.nlm.nih.gov/pmc/articles/PMC6597140

- Stavrou GA, Donati M, Faiss S, et al. Perihilar cholangiocarcinoma (Klatskin tumor) Chirurg. 2014;85(2):155–65. quiz 166–67.

- Molina V, Sampson J, Ferrer J, et al. Klatskin tumor: Diagnosis, preoperative evaluation and surgical considerations. Cir Esp. 2015;93(9):552–60.

- Welzel T.M., McGlynn K.A. (2011) Klatskin Tumors. In: Schwab M. (eds) Encyclopedia of Cancer. Springer, Berlin, Heidelberg. https://doi.org/10.1007/978-3-642-16483-5

- Shin HR, Oh JK, Masuyer E, et al. Epidemiology of cholangiocarcinoma: An update focusing on risk factors. Cancer Sci. 2010;101(3):579–85.

- Shaib YH, El-Serag HB, Nooka AK, et al. Risk factors for intrahepatic and extrahepatic cholangiocarcinoma: A hospital-based case-control study. Am J Gastroenterol. 2007;102(5):1016–21.

- Mansour JC, Aloia TA, Crane CH, et al. Hilar cholangiocarcinoma: Expert consensus statement. HPB (Oxford) 2015;17(8):691–99.

- Jarnagin W, Winston C. Hilar cholangiocarcinoma: Diagnosis and staging. HPB (Oxford) 2005;7(4):244–51.

- Staging of Perihilar Bile Duct Cancers. https://www.cancer.org/cancer/bile-duct-cancer/detection-diagnosis-staging/staging/staging-extrahepatic-bile-duct.html

- Matsuo K, Rocha FG, Ito K, et al. The Blumgart preoperative staging system for hilar cholangiocarcinoma: Analysis of resectability and outcomes in 380 patients. J Am Coll Surg. 2012;215(3):343–55.

- Song SC, Choi DW, Kow AW, et al. Surgical outcomes of 230 resected hilar cholangiocarcinoma in a single centre. ANZ J Surg. 2013;83(4):268–74.

- Cheng Q, Luo X, Zhang B, et al. Predictive factors for prognosis of hilar cholangiocarcinoma: Postresection radiotherapy improves survival. Eur J Surg Oncol. 2007;33(2):202–7.

- Parikh AA, Abdalla EK, Vauthey JN. Operative considerations in resection of hilar cholangiocarcinoma. HPB (Oxford) 2005;7(4):254–58.

- Witzigmann H, Wiedmann M, Wittekind C, Mössner J, Hauss J. Therapeutical concepts and results for Klatskin tumors. Dtsch Arztebl Int. 2008;105(9):156–161. doi:10.3238/arztebl.2008.0156 https://www.ncbi.nlm.nih.gov/pmc/articles/PMC2696740