What is Meigs syndrome

Meigs syndrome is defined as the triad of benign ovarian tumor with ascites (abnormal buildup of fluid in the abdomen) and pleural effusion (abnormal buildup of fluid in the pleural space between the lungs and chest cavity) that resolves after resection of the tumor 1. Histologically, the benign ovarian tumor may be a fibroma, thecoma, cystadenoma, or granulosa cell tumor. Ovarian fibromas constitute the majority of the benign tumors seen in Meigs syndrome. Meigs syndrome, however, is a diagnosis of exclusion, only after ovarian carcinoma is ruled out 2.

Pseudo-Meigs syndrome consists of pleural effusion, ascites, and benign tumors of the ovary other than fibromas. These benign tumors include those of the fallopian tube or uterus and mature teratomas, struma ovarii, and ovarian leiomyomas 3. This terminology sometimes also includes ovarian or metastatic gastrointestinal malignancies 1.

Pseudo-pseudo Meigs syndrome includes patients with systemic lupus erythematosus and enlarged ovaries 4.

Atypical Meigs characterized by a benign pelvic mass with right-sided pleural effusion but without ascites has been reported at least twice. As in Meigs syndrome, pleural effusion resolves after removal of the pelvic mass.

Life expectancy of patients with Meigs syndrome mirrors that of the general population after surgery, and less than 1% of fibromas progress to fibrosarcoma.

Although Meigs syndrome mimics a malignant condition, it is a benign disease and has a very good prognosis if properly managed. Life expectancy after surgical removal of the tumor is the same as the general population 5.

Meigs syndrome causes

Ascites is present in 10-15% of Meigs syndrome cases, and hydrothorax is found in only 1% of Meigs syndrome cases 6. When an ovarian mass is associated with Meigs syndrome and an elevated CA-125 serum level, a malignant process may be suspected until proven otherwise histologically. A negative cytologic examination result of ascitic effusion, the absence of peritoneal implantation, and benign histology should limit surgical procedures. This decision should be made by an experienced gynecologic surgeon or a gynecologic oncologist.

Case reports exist of pseudo-Meigs syndrome associated with malignant struma ovarii and elevated CA-125 levels 7. The choice of not performing adjuvant therapy is feasible after optimal surgery and adequate staging procedure given to the usually clinical benign course and the low incidence of metastases in malignant struma ovarii. Struma ovarii is a rare cause of ascites, hydrothorax, elevated CA-125 levels, and hyperthyroidism 8. This rare condition should be considered in the differential diagnosis in patients with ascites and pleural effusions but with negative cytologic test results.

Liao and colleagues 9 reported a case of right benign struma ovarii in a patient presenting with ascites and CA-125 of 3515 U/Ml, who presented complete remission of symptoms and return to normal CA-125 after surgical resection of the mass.

The combination of ascites, pleural effusion, CA-125 level elevation, and no tumor in a patient with systemic lupus erythematosus is either a Tjalma syndrome or due to the migrated Filshie clips a pseudo-Meigs syndrome 10.

Cause of ascitic fluid

The pathophysiology of ascites in Meigs syndrome is speculative. Meigs suggested that irritation of the peritoneal surfaces by a hard, solid ovarian tumor could stimulate the production of peritoneal fluid. Samanth and Black studied ovarian tumors accompanied by ascites and found that only tumors larger than 10 cm in diameter with a myxoid component to the stroma are associated with ascites 11. These authors believe that their observations favor secretion of fluid from the tumor as the source of the ascites.

Other proposed mechanisms are direct pressure on surrounding lymphatics or vessels, hormonal stimulation, and tumor torsion. Development of ascites may be due to release of mediators (eg, activated complements, histamines, fibrin degradation products) from the tumor, leading to increased capillary permeability.

Origin of pleural effusion

The etiology of pleural effusion is unclear. Efskind and Terada et al theorize that ascitic fluid is transferred via transdiaphragmatic lymphatic channels. The size of the pleural effusion is largely independent of the amount of ascites. The pleural fluid may be located on the left side or may be bilateral 5.

Efskind injected ink into the lower abdomen of a woman with Meigs syndrome and found that the ink particles accumulated in the lymphatics of the pleural surface within half an hour. Blockage of these lymphatics prevented accumulation of pleural fluid and caused an increase in ascitic fluid.

In 1992, Terada and colleagues injected labeled albumin into the peritoneum and found that the maximum concentration was detected in the right pleura within 3 hours.

Nature of the ascitic and pleural fluid

Ascitic fluid and pleural fluid in Meigs syndrome can be either transudative or exudative 12. Meigs performed electrophoresis on several cases and determined that pleural and ascitic fluids were similar in nature. Tumor size, rather than the specific histologic type, is thought to be the important factor in the formation of ascites and accompanying pleural effusion.

In 2015, the findings of Krenke et al 13. in their systematic literature review of 541 cases reported with Meig’s syndrome revealed that an exudative origin in pleural effusions was significantly more prevalent than the ones from transudative origin.

Meigs syndrome symptoms

Patients with Meigs syndrome may have a family history of ovarian cancer. The chief complaints are vague and generally manifest over time; they include the following:

- Fatigue

- Shortness of breath

- Increased abdominal girth

- Weight gain/weight loss

- Nonproductive cough

- Bloating

- Amenorrhea for premenopausal women

- Menstrual irregularity

Positive signs include the following:

- Vital signs – Tachypnea, tachycardia

- Lungs – Dullness to percussion; decreased tactile fremitus; decreased vocal resonance; decreased breath sounds, suggesting pleural effusion, which is mostly observed on the right side but can also be left sided

- Abdomen – Most patients present with an asymptomatic, solid, and unilateral pelvic mass, most often left sided; the mass may be large, but sometimes, no mass is felt; ascites is present, with shifting dullness and/or fluid thrill 6

- Pelvis – Examination reveals a pelvic mass

Meigs syndrome diagnosis

Laboratory Studies

Complete blood count

Complete blood count (CBC) provides information about hemoglobin, hematocrit, and platelet levels. A low hemoglobin count requires further workup, including reticulocyte count, total iron-binding capacity, and iron and ferritin levels. Anemia in patients with Meigs syndrome is most likely due to iron deficiency. Anemia can be corrected emergently by blood transfusion in patients undergoing surgery for Meigs syndrome. Anemia can be treated with iron supplementation postoperatively.

Basic metabolic profile

Studies of sodium, potassium, chloride, bicarbonate, blood urea nitrogen, creatinine, and glucose levels are included. These electrolytes are checked before the patient undergoes surgery. If necessary, corrections of these electrolytes are made.

Prothrombin time

Prothrombin time is checked before surgery. If elevated, it is a marker of coagulopathy. Elevated prothrombin time is corrected before surgery, either by administering vitamin K to the patient or by transfusing fresh frozen plasma.

Serum cancer antigen 125 test

Other than serum electrolytes and CBC count, the study of interest is the serum cancer antigen 125 (CA-125) test. Tumor marker serum levels of CA-125 can be elevated in Meigs syndrome, but the degree of elevation does not correlate with malignancy. In fact, a normal CA-125 level does not exclude the possibility of malignancy 14. The CA-125 level is not used as a screening test. Immunohistochemical studies suggest that serum CA-125 elevation in patients with Meigs syndrome is caused by mesothelial expression of the antigen rather than by fibroma 2. The highest reported level of CA-125 after laparotomy is 1808 U/mL. This would be a false-positive result.

Physiologic sources of CA-125 are fetal coelomic epithelium and its derivatives, including the following:

- Müllerian epithelium

- Pleura

- Pericardium

- Peritoneum

Pathologic conditions related to an elevated CA-125 level include the following:

- Pelvic inflammatory disease (PID)

- Peritoneal damage or regeneration (eg, abdominal surgery)

- Ovarian malignancy

- Endometriosis

In 1992, Lin et al 15 conducted a study to determine whether the ovarian fibroma was the source of serum CA-125 elevation. Using an immunohistochemical technique specific for the tumor marker, they localized CA-125 expression in the omentum and peritoneal surfaces rather than in the fibroma.

Papanicolaou test

Papanicolaou test findings are normal.

Imaging Studies

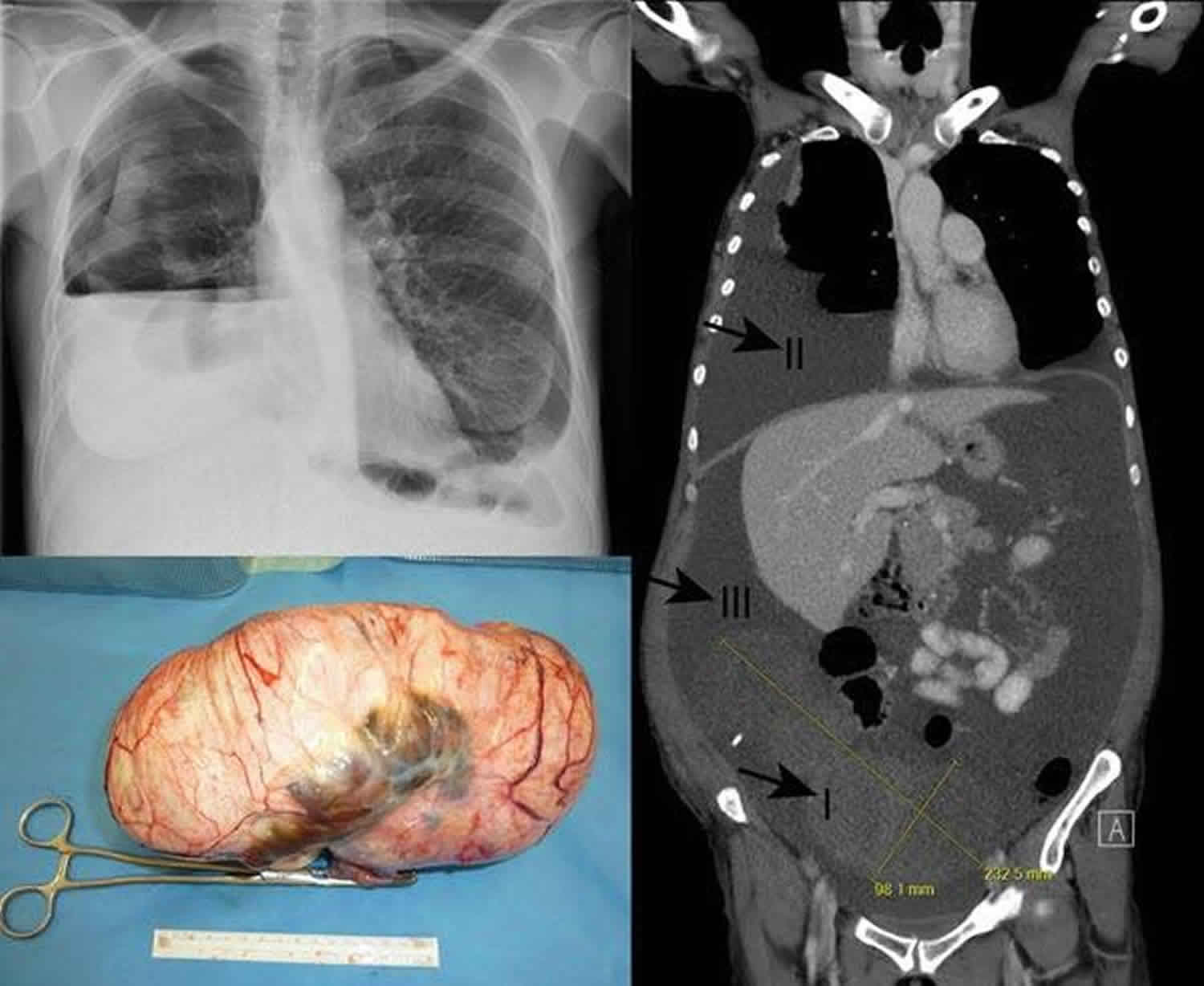

Chest radiography confirms pleural effusion.

- Abdominal and pelvic ultrasound confirms the ovarian mass and ascites.

CT scan of the abdomen and pelvis

- CT scanning confirms ascites and ovarian, uterine, fallopian tube, or broad ligament mass.

- No signs of distant metastasis are observed.

Procedures

Paracentesis

- Ascitic fluid is mostly transudative. Findings are negative for malignant cells but can be positive for reactive mesothelial cells.

Thoracentesis

- Pleural fluid is usually transudative. Findings can be exudative and negative for malignant cells.

Histologic Findings

Ovarian tumors are divided into the following histologic subgroups, and Meigs syndrome can be observed with any of the benign tumors.

Coelomic epithelial tumors

These tumors, which originate from the coelomic epithelium, constitute 80-85% of all ovarian tumors.

- Serous cystadenoma and mucinous cystadenoma: 15-20% are malignant.

- Endometrioid type and clear cell: 95-98% are malignant.

- Brenner tumor: 2% are malignant.

Germ cell tumors

These tumors originate from the germ cell and constitute 10-15% of all ovarian tumors. All are malignant except mature teratomas and gonadoblastomas, which are always benign.

- Mature teratoma

- Immature teratoma

- Dysgerminoma

- Gonadoblastoma

- Endodermal sinus

- Embryonal carcinoma

- Nongestational choriocarcinoma

Gonadal-stromal cell tumors

Gonadal-stromal cell tumors constitute 3-5% of all tumors.

- Granulosa cell

- Fibroma: Fewer than 5% are malignant.

- Thecoma: Fewer than 5% are malignant.

- Sertoli-Leydig cell: Fewer than 5% are malignant.

- Lipid cell type: 30% are malignant.

- Gynandroblastoma: 100% are malignant.

Meigs syndrome treatment

Medical care of patients with Meigs syndrome is intended to provide symptomatic relief of ascites and pleural effusion by means of therapeutic paracentesis and thoracentesis.

Consult with a gynecologic surgeon for surgical management of the patient.

Consult with a pulmonologist for management of pleural effusion. Medical pleuroscopy is typically not indicated but may be useful in complicated patients.

Activity

Patients can maintain activities as tolerated.

Surgical Care

- Resolution after tumor resection has been widely documented 16.

- Exploratory laparotomy with surgical staging is the treatment of choice. Perform a frozen section of the ovarian mass during exploratory laparotomy. If the frozen section is consistent with benign tumor, conservative surgery (salpingo-oophorectomy or oophorectomy) is appropriate. Findings of lymph node biopsies and omentum and pelvic washings are negative for malignancy if these procedures are performed during surgery.

- In women of reproductive age, perform unilateral salpingo-oophorectomy.

- In postmenopausal women, options include bilateral salpingo-oophorectomy with total hysterectomy and unilateral or occasionally bilateral salpingo-oophorectomy.

- In prepubertal girls, options include wedge resection of ovary and unilateral salpingo-oophorectomy.

- The cure rate after either type of surgery is high and recurrence is rare.

As described by Meigs, ascites and pleural effusion resolve dramatically within a few weeks to months after removal of the pelvic mass, without any recurrence. Use of chest ultrasound to follow pleural effusion progression is superior to chest radiography in identifying residual pleural effusion and can detect amounts as small as 3-5 mL 2.

The serum CA-125 level also returns to normal after surgery.

Meigs syndrome prognosis

Meig’s syndrome is a benign disease, if properly treated. No recurrence after sugical removal of the mass has been reported.

Clinicans should be aware of this rare and treatable condition.

References- Meigs Syndrome. https://emedicine.medscape.com/article/255450-overview

- Riker D, Goba D. Ovarian mass, pleural effusion, and ascites: revisiting meigs syndrome. J Bronchology Interv Pulmonol. 2013 Jan. 20(1):48-51.

- Dunn JS Jr, Anderson CD, Method MW. Hydropic degenerating leiomyoma presenting as pseudo-Meigs syndrome with elevated CA 125. Obstet Gynecol. 1998 Oct. 92(4 Pt 2):648-9.

- Schmitt R, Weichert W, Schneider W, Luft FC, Kettritz R. Pseudo-pseudo Meigs’ syndrome. Lancet. 2005 Nov 5. 366(9497):1672.

- Park JW, Bae JW. Postmenopausal Meigs’ Syndrome in Elevated CA-125: A Case Report. J Menopausal Med. 2015 Apr. 21 (1):56-9.

- Loue VA, Gbary E, Koui S, Akpa B, Kouassi A. Bilateral Ovarian Fibrothecoma Associated with Ascites, Bilateral Pleural Effusion, and Marked Elevated Serum CA-125. Case Rep Obstet Gynecol. 2013. 2013:189072.

- Loizzi V, Cormio G, Resta L, Fattizzi N, Vicino M, Selvaggi L. Pseudo-Meigs syndrome and elevated CA125 associated with struma ovarii. Gynecol Oncol. 2005 Apr. 97(1):282-4.

- Zannoni GF, Gallotta V, Legge F, Tarquini E, Scambia G, Ferrandina G. Pseudo-Meigs’ syndrome associated with malignant struma ovarii: a case report. Gynecol Oncol. 2004 Jul. 94(1):226-8.

- Liao Q, Hu S. Meigs’ Syndrome and Pseudo-Meigs’ Syndrome: Report of Four Cases and Literature Reviews. Journal of Cancer Therapy. Journal of cancer therapy. 2015 April. 6(04):293.

- Tjalma WA. Ascites, pleural effusion, and CA 125 elevation in an SLE patient, either a Tjalma syndrome or, due to the migrated Filshie clips, a pseudo-Meigs syndrome. Gynecol Oncol. 2005 Apr. 97(1):288-91.

- Samanth KK, Black WC. Benign ovarian stromal tumors associated with free peritoneal fluid. Am J Obstet Gynecol. 1970 Jun 15. 107(4):538-45.

- CIFDS G, André SA, Maggi L, Nogueira FJ. Syndrome with Elevated CA 125: Case Report with a Journey through Literature. J Pulm Respir Med. 2015. 5(303):2.

- Krenke R, Maskey-Warzechowska M, Korczynski P, Zielinska-Krawczyk M, Klimiuk J, Chazan R, et al. Pleural Effusion in Meigs’ Syndrome-Transudate or Exudate?: Systematic Review of the Literature. Medicine (Baltimore). 2015 Dec. 94 (49):e2114.

- Jones OW, Surwit EA. Meigs syndrome and elevated CA 125. Obstet Gynecol. 1989 Mar. 73(3 Pt 2):520-1.

- Lin JY, Angel C, Sickel JZ. Meigs syndrome with elevated serum CA 125. Obstet Gynecol. 1992 Sep. 80(3 Pt 2):563-6.

- Danilos J, Michał Kwaśniewski W, Mazurek D, Bednarek W, Kotarski J. Meigs’ syndrome with elevated CA-125 and HE-4: a case of luteinized fibrothecoma. Prz Menopauzalny. 2015 Jun. 14 (2):152-4