Paradoxical embolism

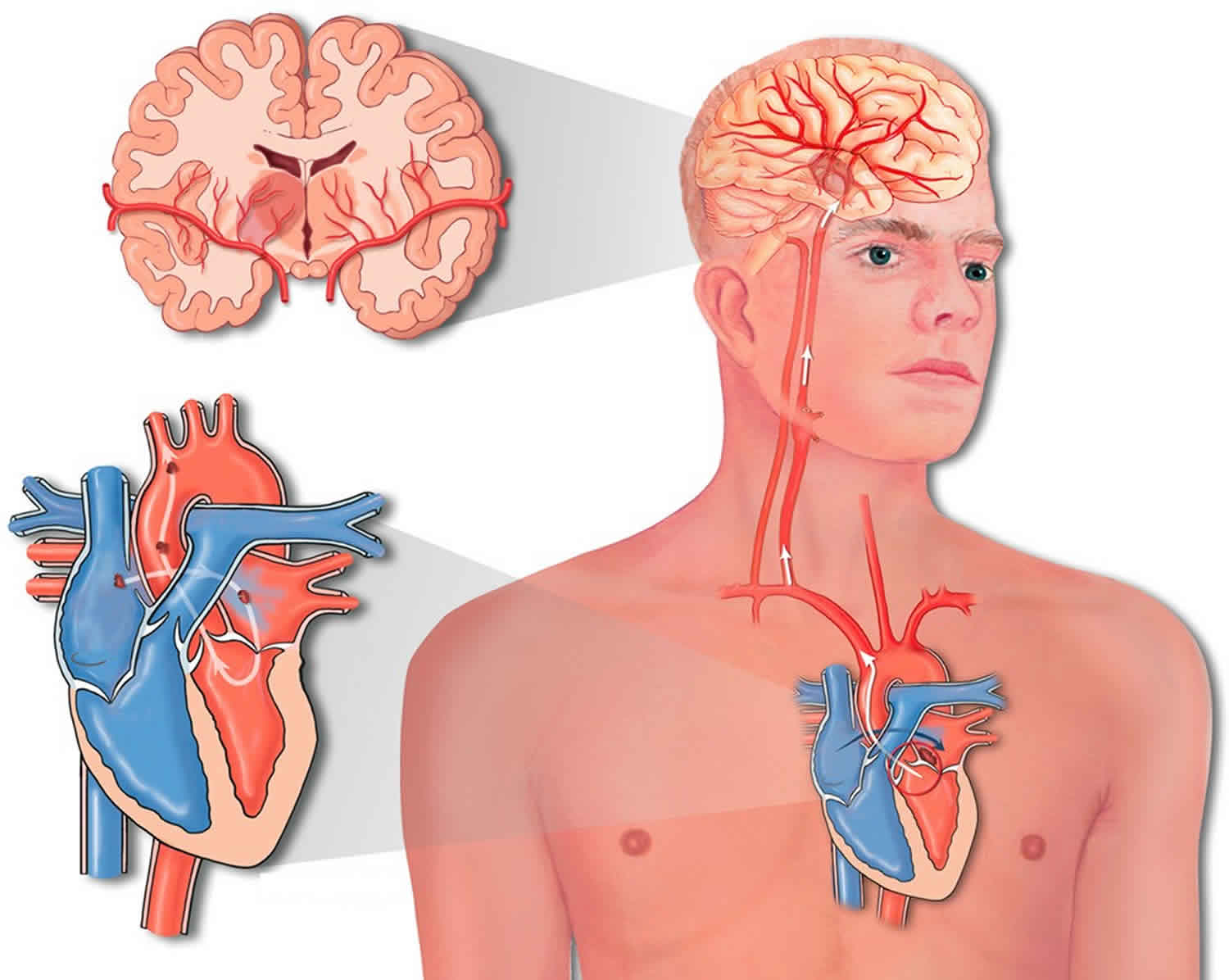

Paradoxical embolism refers to the blockage of an artery due to a passage of a clot from a systemic vein to a systemic artery without passing through the lungs, which ordinarily acts as a filter to remove blood clots from entering the arterial circulation 1. Paradoxical embolism is a clinical scenario in which an embolism arising in the venous system crosses into the arterial circulation where it causes tissue infarction. The most common clinically important site of embolization is the cerebral circulation.

Paradoxical embolism occurs when there is a defect that allows a clot to cross directly from the right to the left side of the heart, as in patients with atrial septal defect or patent foramen ovale (PFO) 1. Once in the arterial circulation, a clot can travel to any site where it can block an artery. Paradoxical embolism is frequently associated with cryptogenic stroke, peripheral embolism, and brain abscess 2. Cardiac sources account for 80% of all peripheral arterial thromboembolic events 3. Paradoxical embolism is comparatively rare and is recognized for less than 2% of systemic arterial emboli 4. However, the importance of paradoxical embolism might be underestimated. Clinically, doctors often encounter patients with acute arterial embolisms with no identifiable significant atherosclerotic risk factors and can not find the sources of thrombus despite a thorough examination. Meacham et al 5 reported that paradoxical embolism could account for as many as 47,000 unexplained ischemic strokes each year in the United States.

The distribution of arterial emboli in paradoxical embolism has differed among studies. According to D’Audiffret et al 6, the extremity arteries (55%) and cerebral arteries (37–50%) represented the most frequent targets; the visceral and coronary arteries were rarer targets (6–9% and 7–9%, respectively). Dubiel et al 7 found the cerebrum as the most targeted (89.4%) area, with 57.8% cases of cerebral embolism and 31.7% cases of transient ischemic attacks; others were coronary (8.9%) and peripheral (1.7%) embolisms. In Zhang et al case series 1, the cerebrum (58.3%) was the most commonly affected site, followed by the renal and mesentery arteries (16.7% respectively).

Paradoxical embolism with descending aorta thrombus and thrombus-straddled patent foramen ovale (PFO) was exceedingly rare with only several case reports 8. In a study by Loscalzo 9, 23% of their cases had 2 separate embolic sites, and 10% had 3. Dubiel et al 7 found that 12.8% of their patients with paradoxical embolism experienced multifocal arterial embolisms.

Paradoxical embolism causes

Paradoxical embolism can occur only when there is an abnormal vascular or intracardiac defect 1. The most common defect associated with paradoxical embolism was patent foramen ovale (PFO). The closure of the foramen ovale is normally complete before the age of 2 years. If the foramen ovale was incompletely closed, it could be normally kept sealed by a pressure gradient between the left and right atrium but might be opened when the right atrial pressure increases and exceeds the left atrial pressure 10. Thus, the foramen ovale serves as a potential route for emboli arising from the right side of the heart. The incidence of patent foramen ovale (PFO) was 20.8% in the general population 11. In a study of 180 patients with paradoxical embolism, 125 (69.4%) patients had a patent foramen ovale (PFO), 63 (35%) had an atrial septal aneurysm, 24 (13.3%) had a patent foramen ovale (PFO)-like septal defect, and 31 (17.2%) had an atrial septal defect 7.

Patent foramen ovale (PFO) is a left to right shunt that occurs between the septum primum and septum secundum. However, Valsalva maneuvers such as coughing, squatting, or defecating can transiently increase right atrial pressure leading to a transient shunt reversal, resulting in the transferring of potential thrombi into systemic circulation.

Atrial septal defects (ASD) are congenital defects that vary in size and location, with clinical manifestations that range from atrial tachyarrhythmias to dyspnea. Atrial septal defects lead to a left to right shunt as well as a fixed split S2 on cardiac exam, however transient reversal in flow can reverse the shunt. Atrial septal defects are associated with a paradoxical embolism in up to 14% of patients 12.

Ventricular septal defects (VSD) commonly result in left to right shunts, however certain conditions that increase right atrial pressure like Eisenmenger syndrome can reverse the shunt, allowing for paradoxical embolism.

Pulmonary arteriovenous malformations are usually hereditary and are a pathological connection between the pulmonary arteries to the pulmonary veins returning to the left atrium. This leads to a permanent right to left shunt. Patients with a history of Hereditary Hemorrhagic Telangiectasia are at increased risk for pulmonary arteriovenous malformation and subsequent paradoxical embolism 13.

Paradoxical embolism symptoms

Physicians should strongly suspect paradoxical embolism in patients with an embolic event with a non-identifiable source such as atrial fibrillation, and a concomitant intracardiac shunt or pulmonary arteriovenous malformation. Physicians should be suspicious for paradoxical embolism when patients present with a systemic cryptogenic embolism with a recent or current history of DVT. Physicians should gather a history of factors that lead to the event such as coughing or straining. Physicians should also gather a history screening for DVT, cardiovascular disease, and stroke. History of migraines occurs in up to 50% of patients with an intracardiac shunt. Physicians should look for signs of congenital heart defects such as right ventricular hypertrophy, digital clubbing, or fixed S2 splitting.

Paradoxical embolism diagnosis

Diagnosis of paradoxical embolism is that of exclusion, and other common causes of stroke should be ruled out first. EKG should be performed to assess for atrial fibrillation. Transthoracic echocardiogram with color-flow Doppler is the diagnostic imaging modality for evaluation of intracardiac shunts, cardiac myxomas, and thrombus formations. Agitated saline or contrast can also be injected during transthoracic echocardiogram to help visualize and diagnose an intracardiac shunt. However, to accurately diagnose a patent foramen ovale (PFO), the saline or contrast needs to be injected at the end of a Valsalva maneuver where the left of right shunt transiently reverses. The transthoracic echocardiogram can also evaluate the presence of aortic plaques in the ascending aorta which can be a cause of systemic embolization. While transthoracic echocardiogram is limited to evaluating intracardiac shunts, transcranial Doppler sonography can be used to detect any shunt including pulmonary arteriovenous malformation. Transcranial Doppler sonography is non-invasive and can be done at the bedside by injecting agitated contrast into a peripheral line and looking for microemboli in the middle cerebral artery. Ear oximetry is a simple screening tool for intracardiac shunts that can be utilized with high sensitivity and specificity. When the patient performs a Valsalva maneuver, the left to right shunt transiently turns into a right to left shunt, resulting in a transient decrease in the arterial oxygen saturation which the ear oximeter can detect 14.

According to Johnson 15, the diagnosis of paradoxical embolism should be considered in the presence of:

- A systemic arterial embolus that did not arise from the left side of the heart,

- Venous thrombosis and /or pulmonary embolism, or

- An intracardiac communication that permitted a right-to-left shunt.

The diagnosis of paradoxical embolism was termed definitive when made at autopsy or when a thrombus is seen crossing an intracardiac defect during echocardiography of an arterial embolus 5 and considered presumptive if the 3 criteria were fulfilled 9. The clinical diagnosis of paradoxical embolism requires at least 2 of the 3 criteria 16.

Paradoxical embolism treatment

Treatment of paradoxical embolism included surgical embolectomy, thrombolysis, and anticoagulation. The choice of treatment options and its specific plan is dependent on the risk of stroke recurrence, the lifelong benefit/risk ratio between thrombolysis, and anticoagulation and surgery, as well as the cost of each intervention. The surgical approach includes embolectomy and closure of intracardiac shunts (eg, a patent foramen ovale [PFO] or an atrial septal defect [ASD]) and pulmonary arteriovenous malformations are the surgical treatments of choice and are widely used in patients with presumed paradoxical embolism 17. Medical therapy is comprised of antithrombotic therapy which includes aspirin, or clopidogrel as monotherapy or taken in combination with warfarin for the prevention of thrombotic events. Thrombolytics therapy includes alteplase, streptokinase, and reteplase.

The presence of paradoxical embolism in association with pulmonary embolism (PE) or atrial clots increases mortality. However, the overall survival appeared equivalent among these 3 therapeutic options 18, although more complications occurred with anticoagulation and thrombolysis 8. Ward et al 19 recommended that hemodynamically significant paradoxical embolism should be treated with thrombolytic therapy.

Prevention remains controversial. Whether prophylaxis benefits persons with a recognized predisposition for paradoxical embolism and whether routine screening for patent foramen ovale or atrial septal defect with contrast echocardiography is advisable for patients with hypercoagulable states are yet to be determined.

After a first paradoxical embolism, the risk of recurrence was 3.4–3.8% per year 7. Nendaz et al 20 recommended observation, antiplatelet and anticoagulation therapies, and closure of the patent foramen ovale (PFO) for the prevention of recurrent arterial emboli after paradoxical embolism. Ward et al 19 suggested that warfarin should be continued for 3–6 months or indefinitely if the patient had a patent foramen ovale (PFO) or pulmonary hypertension. In a systematic review, Khairy et al 21 demonstrated that an implantation of a PFO closure device could prevent recurrent thromboembolic events better than a medical therapy alone (warfarin or salicylate). However, Travis et al 22 recommended closure of a PFO for patients with paradoxical embolism only in whom a systemic anticoagulant was contraindicated. Decousus et al 23 reported a reduction in the occurrence of symptomatic or asymptomatic pulmonary embolism after inferior vena cava filter implantation in patients with proximal DVT. In 8 patients with a complete follow-up in this study, 1 out of the 3 PFOs was repaired; 2 patients were implanted with an inferior vena cava filter; they are all still on medication because they had an unsealed PFO, recurrence of DVT, persistent risk factors for thrombosis, or residual thrombus in the lower limb or pulmonary artery. There was no sign of pulmonary or arterial emboli nora clinically significant bleeding. The Cryptogenic Stroke Study has demonstrated that in patients with PFO, there was no significant difference in the time to the primary end points between those treated with warfarin and those treated with aspirin 24. Two of our patients who independently changed their treatment from warfarin to aspirin continued to perform well in their daily living.

References- Zhang HL, Liu ZH, Luo Q, Wang Y, Zhao ZH, Xiong CM. Paradoxical embolism: Experiences from a single center. Chronic Dis Transl Med. 2017;3(2):123–128. Published 2017 Mar 30. doi:10.1016/j.cdtm.2017.02.005 https://www.ncbi.nlm.nih.gov/pmc/articles/PMC5627697

- Inoue T., Tadehara F., Hinoi T. Paradoxical peripheral embolism coincident with acute pulmonary thromboembolism. Intern Med. 2005;44:243–245.

- AbuRahma A.F., Richmond B.K., Robinson P.A. Etiology of peripheral arterial thromboembolism in young patients. Am J Surg. 1998;1762:158–161.

- d’Audiffret A., Shenoy S.S., Ricotta J.J., Dryjski M. The role of thrombolytic therapy in the management of paradoxical embolism. Cardiovasc Surg. 1998;6:302–306.

- Meacham R.R., 3rd, Headley A.S., Bronze M.S., Lewis J.B., Rester M.M. Impending paradoxical embolism. Arch Intern Med. 1998;158:438–448.

- d’Audiffret A., Pillai L., Dryjski M. Paradoxical emboli: the relationship between patent foramen ovale, deep vein thrombosis and ischaemic stroke. Eur J Vasc Endovasc Surg. 1999;17:468–471.

- Dubiel M., Bruch L., Liebner M. Exclusion of patients with arteriosclerosis reduces long-term recurrence rate of presumed arterial embolism after PFO closure. J Interv Cardiol. 2007;20:275–281.

- Willis S.L., Welch T.S., Scally J.P. Impending paradoxical embolism presenting as a pulmonary embolism, transient ischemic attack, and myocardial infarction. Chest. 2007;132:1358–1360.

- Loscalzo J. Paradoxical embolis: clinical presentation, diagnostic strategies, and therapeutic options. Am Heart J. 1986;112:141–145.

- Wilmshurst P.T., de Belder M.A. Patent foramen ovale in adult life. Br Heart J. 1994;71:209–212.

- Petty G.W., Khandheria B.K., Meissner I. Population-based study of the relationship between patent foramen ovale and cerebrovascular ischemic events. Mayo Clin Proc. 2006;81:602–608.

- Bannan A, Shen R, Silvestry FE, Herrmann HC. Characteristics of adult patients with atrial septal defects presenting with paradoxical embolism. Catheter Cardiovasc Interv. 2009 Dec 01;74(7):1066-9.

- Kjeldsen AD, Oxhøj H, Andersen PE, Green A, Vase P. Prevalence of pulmonary arteriovenous malformations (PAVMs) and occurrence of neurological symptoms in patients with hereditary haemorrhagic telangiectasia (HHT). J. Intern. Med. 2000 Sep;248(3):255-62.

- Karttunen V, Ventilä M, Ikäheimo M, Niemelä M, Hillbom M. Ear oximetry: a noninvasive method for detection of patent foramen ovale: a study comparing dye dilution method and oximetry with contrast transesophageal echocardiography. Stroke. 2001 Feb;32(2):448-53.

- Johnson B.I. Paradoxical embolism. J Clin Pathol. 1951;4:316–332.

- Ucar Ozgul, Golbasi Zehra, Gulel Okan, Yildirim Nesligul. Paradoxical and pulmonary embolism due to a thrombus entrapped in a patent foramen ovale. Tex Heart Inst J. 2006;33:78–80.

- Wahl A, Jüni P, Mono ML, Kalesan B, Praz F, Geister L, et al. Long-term propensity score-matched comparison of percutaneous closure of patent foramen ovale with medical treatment after paradoxical embolism. Circulation. 2012 Feb 14. 125 (6):803-12.

- Bang OY, Lee MJ, Ryoo S, Kim SJ, Kim JW. Patent Foramen Ovale and Stroke-Current Status. J Stroke. 2015 Sep. 17 (3):229-37.

- Ward R., Jones D., Haponik E.F. Paradoxical embolism: an underrecognized problem. Chest. 1995;108:549–558.

- Nendaz M., Sarasin F.P., Bogousslavsky J. How to prevent stroke recurrence in patients with patent foramen ovale: anticoagulants, antiaggregants, foramen closure, or nothing? Eur Neurol. 1997;37:199–204.

- Khairy P., O’Donnell C.P., Landzberg M.J. Transcatheter closure versus medical therapy of patent foramen ovale and presumed paradoxical thromboemboli: a systematic review. Ann Intern Med. 2003;139:753–760.

- Travis J.A., Fuller S.B., Ligush J., Jr., Plonk G.W., Jr., Geary R.L., Hansen K.J. Diagnosis and treatment of paradoxical embolus. J Vasc Surg. 2001;34:860–865.

- Decousus H., Leizorovicz A., Parent F. A clinical trial of vena filters in the prevention of pulmonary embolism in patients with proximal deep-vein thrombosis. Prevention du Risque d’Embolie Pulmonaire par Interruption Cave Study Group. N Engl J Med. 1998;338:409–415.

- Homma S., Sacco R.L., Di Tullio M.R. PFO in Cryptogenic Stroke Study (PICSS) Investigators. Effect of medical treatment in stroke patients with patent foramen ovale: patent foramen ovale in Cryptogenic Stroke Study. Circulation. 2002;105:2625–2631.