Monoarthritis

Monoarthritis refers to inflammation (arthritis) of one joint with the clinical presentation of pain or swelling in a single joint 1. Acute monoarthritis can be the initial manifestation of many joint disorders 2. The most common diagnoses in the primary care setting are osteoarthritis, gout, and trauma. A delay in diagnosis and treatment, particularly in septic arthritis, can have catastrophic results including sepsis, bacteremia, joint destruction, or death 3. The history and physical examination can help guide the use of laboratory and imaging studies. The presence of focal bone pain or recent trauma requires radiography of the affected joint to rule out metabolic bone disease, tumor, or fracture. If there is a joint effusion in the absence of trauma or recent surgery, and signs of infection (e.g., fever, erythema, warmth) are present, subsequent arthrocentesis should be performed. Inflammatory synovial fluid containing monosodium urate crystals indicates a high probability of gout. Noninflammatory synovial fluid suggests osteoarthritis or internal derangement. Pitfalls in the diagnosis and early treatment of acute monoarthritis include failure to perform arthrocentesis, administering antibiotics before aspirating the joint when septic arthritis is suspected (or failing to start antibiotics after aspiration), and starting treatment based solely on laboratory data, such as an elevated uric acid level 4.

Monoarthritis causes

Any condition that may cause joint pathology can initially present as monoarthritis, resulting in a broad differential diagnosis 1. Because of this, monoarthritis has no unifying cause. The most common diagnoses in the primary care setting are osteoarthritis, gout, and trauma 4.

Causes of acute monoarthritis

Common causes of acute monoarthritis

- Avascular necrosis

- Crystals

- Calcium oxalate

- Calcium pyrophosphate dihydrate (pseudogout)

- Hydroxyapatite

- Monosodium urate (gout)

- Hemarthrosis

- Infectious arthritis

- Bacteria

- Fungi

- Lyme disease

- Mycobacteria

- Virus

- Internal derangement

- Osteoarthritis

- Osteomyelitis

- Overuse

- Trauma

Less common causes of acute monoarthritis

- Ankylosing spondylitis

- Bone malignancies

- Bowel disease–associated arthritis

- Hemoglobinopathies

- Juvenile rheumatoid arthritis

- Loose body

- Psoriatic arthritis

- Reactive arthritis

- Rheumatoid arthritis

- Sarcoidosis

- Systemic lupus erythematosus

Rare causes of acute monoarthritis

- Amyloidosis

- Behçet syndrome

- Familial Mediterranean fever

- Foreign-body synovitis

- Hypertrophic pulmonary osteoarthropathy

- Intermittent hydrarthrosis

- Pigmented villonodular synovitis

- Relapsing polychondritis

- Synovial metastasis

- Synovioma

- Systemic onset juvenile idiopathic arthritis (Still disease)

- Vasculitic syndromes

Monoarthritis symptoms

Any acute inflammatory process that develops in a single joint over the course of a few days is considered acute monoarthritis (also defined as monoarthritis that has been present for less than two weeks) 5. Establishing the chronology of symptoms is important (Table 1). Rapid onset over hours to days usually indicates an infection or a crystal-induced process. Fungal or mycobacterial infections usually have an indolent and protracted course but can mimic bacterial arthritis.

Symptoms consistent with osteoarthritis include pain that tends to worsen with activity, morning stiffness lasting less than 30 minutes, and asymmetric joint pain 6. The most commonly affected joints are the hands, knees, hips, and spine 6. Although osteoarthritis often follows an insidious course, acute flare-ups are common and can be mistaken for other causes. The presence of focal bone pain or recent trauma requires radiography of the affected joint to rule out metabolic bone disease, tumor, or fracture 7.

Gout is a common disorder with a 3% prevalence worldwide. It accounts for more than 7 million ambulatory visits in the United States annually 8. Crystal-induced arthritis presents as a rapidly developing monoarthritis with swelling and erythema, and most commonly involves the first metatarsophalangeal joint 8. Over time, the joint space can be irreversibly damaged with tophi formation 9. The presence of monosodium urate crystals indicates gout; these crystals are identified by their needle-like appearance and strong negative birefringence 8. Calcium pyrophosphate dihydrate crystals are polymorphic, weakly positive under birefringent microscopy, and their presence indicates pseudogout 4. Other crystal-induced arthritis etiologies include calcium oxalate and hydroxyapatite 1.

Infection is a common cause of joint pain. When infection is suspected in the presence of a joint effusion or inflammation, arthrocentesis should be performed, in addition to further laboratory testing as indicated. Gonococcal arthritis is the most common type of nontraumatic acute monoarthritis in young, sexually active persons in the United States 10.

Septic arthritis is a key consideration in adults presenting with acute monoarthritis, particularly in the presence of joint pain, erythema, warmth, and immobility 11. The most important risk factors for septic arthritis are a prosthetic joint, skin infection, joint surgery, rheumatoid arthritis, age older than 80 years, diabetes mellitus, and renal disease 10. One study found that among persons presenting with acute joint pain and a predisposing condition, 10% had septic arthritis 7. When septic arthritis is suspected, it is important to begin empiric antibiotics immediately following arthrocentesis, because failure to initiate prompt antibiotic therapy can lead to subchondral bone loss and permanent joint dysfunction 11. The most common route of entry into the joint is hematogenous spread during bacteremia 12; therefore, isolation of the causative agent through synovial fluid culture is essential for the diagnosis and guidance of antibiotic therapy 11.

Less common causes of monoarthritis include systemic diseases such as spondyloarthropathies (e.g., psoriatic arthritis, reactive arthritis, ankylosing spondylitis), sarcoidosis, Behçet syndrome, systemic lupus erythematosus, and rheumatoid arthritis.1 Rheumatic diseases and corticosteroid use can cause avascular necrosis of the bone 1.

Monoarthritis diagnosis

The diagnosis of acute monoarthritis begins with a comprehensive history and physical examination to reveal potential diagnostic clues (Table 1). Key elements of the patient history include a review of systems, age, previous joint disease, recent trauma, medication use, family history of gout, concurrent illness, sexual history, diet, travel history, tick bites, alcohol use, intravenous drug use, and an occupational assessment 4.

Symptoms that worsen with activity and improve with rest suggest a mechanical process, whereas symptoms with an inflammatory process often worsen with rest and present with morning stiffness 1. Osteoarthritis often starts as mild joint inflammation that may initially arouse suspicion for new-onset inflammatory diseases, such as rheumatoid arthritis 13. Morning stiffness and its duration in the affected joint, pain with activity or rest, recent history of trauma, history of previous joint symptoms, and family history of joint inflammation are all important factors that can help differentiate etiologies 11. Osteoarthritis typically worsens with activity, particularly after a period of rest (gelling phenomenon).18 Morning stiffness from osteoarthritis usually lasts for a shorter duration than that of rheumatoid arthritis, which typically lasts 45 minutes or more 6.

A gout attack typically begins at night and peaks within 24 hours, causing pain, swelling, and erythema 13. Common clues from the patient history include obesity, a high-calorie diet, alcohol intake, and the use of loop and thiazide diuretics.8 Trauma may also precipitate an acute gout flare-up 8 and the presentation can closely resemble septic arthritis 13.

Determining whether a condition is truly monoarticular can prove beneficial, because prodromal arthralgias can suggest infection 1. Gonococcal arthritis is often preceded by migratory arthritis and tenosynovitis before settling in a primary joint 1. Conducting a sexual history is imperative, as is documenting any urinary problems, purulent discharge from the urethra, or other signs of infection, such as pharyngitis 11. Risk factors such as intravenous drug use, tick bites, and travel history can lead to a diagnosis of infectious or reactive arthritis 1.

Axial skeleton inflammatory arthritis (e.g., sacroiliitis) in addition to symptoms in a single peripheral joint suggest a spondyloarthropathy 1. Spondyloarthropathies can often present as monoarthritis and progress from joint to joint in a migratory or additive pattern 13. It is important to ask patients about other symptoms, such as enthesopathy (tenderness at the muscle or fascia attachment sites) and dactylitis (sausage-like swelling of fingers or toes), because these are common 13. Some patients also present with ocular inflammation (uveitis) and urethritis (Reiter syndrome).20 A history of skin conditions and a positive family history of inflammatory arthritis suggest psoriatic arthritis, which can present as monoarthritis in the early stages 13.

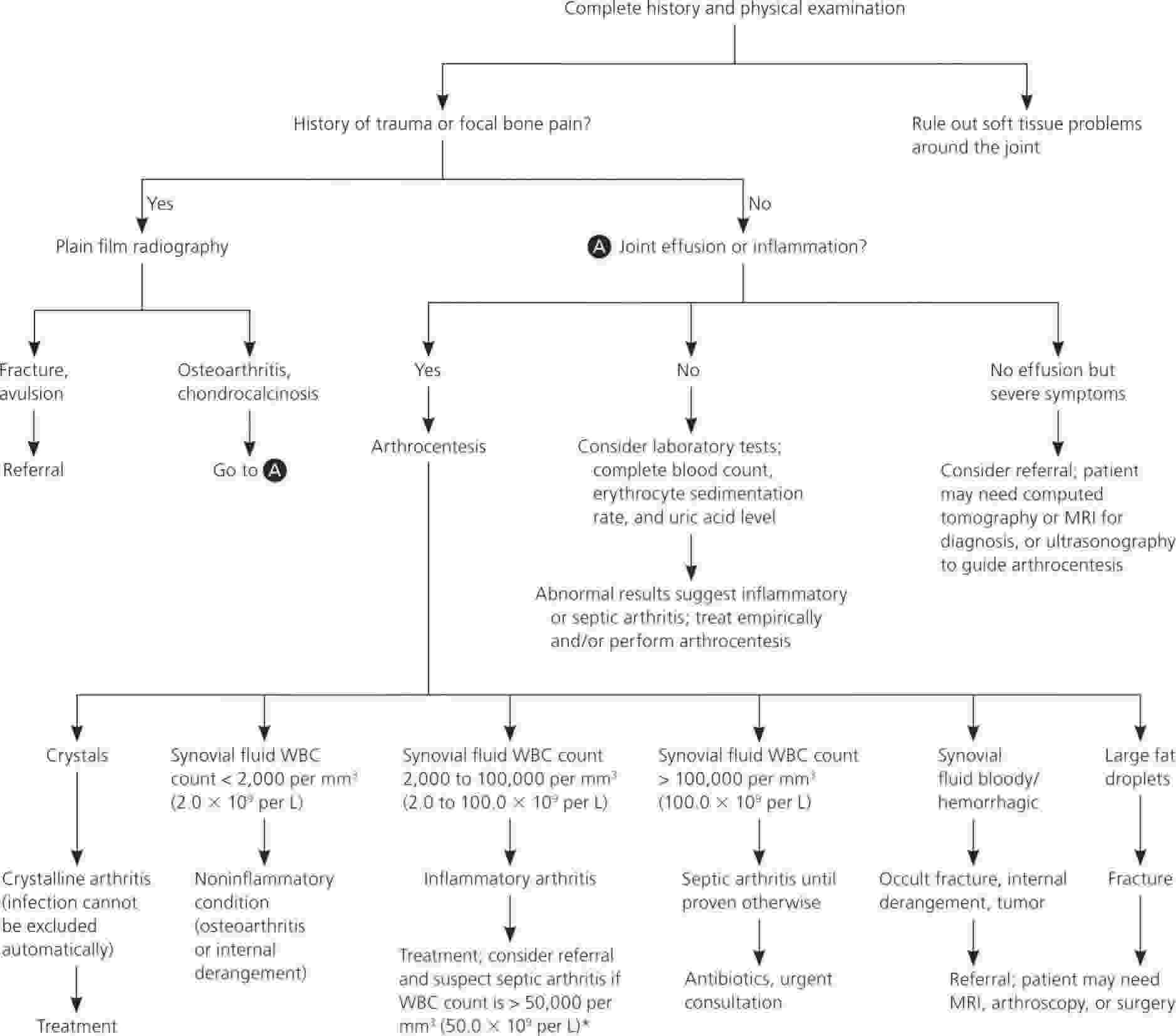

Figure 1. Acute monoarthritis diagnosis

Table 1. Diagnostic clues in patients presenting with monoarthritis

| Clues from history and physical examination | Diagnoses to consider | Evaluation |

|---|---|---|

Active range of motion restricted more than passive range of motion | Periarticular pathology | Radiography and/or MRI if indicated |

Back pain, eye inflammation | Ankylosing spondylitis | HLA-B27 testing, radiography |

Coagulopathy, use of anticoagulants | Hemarthrosis | CBC, ESR, arthrocentesis to confirm diagnosis and rule out infection |

Diuretic medication, presence of tophi, renal stones | Gout | CBC, ESR, uric acid level, arthrocentesis with evaluation for crystals |

Hilar adenopathy, erythema nodosum | Sarcoidosis | CBC, ESR, ACE level, chest radiography, pulmonary referral |

Immunosuppression and/or intravenous drug abuse | Septic arthritis | CBC, ESR, arthrocentesis for cell count and cultures |

Insidious onset of pain and swelling over days to weeks | Indolent infection, osteoarthritis, infiltrative disease, tumor | CBC, ESR, arthrocentesis for cell count and cultures, radiography and possible MRI if tumor is a consideration |

Maximum pain at limits of range of motion (i.e., stress pain) | Osteoarthritis | Radiography |

Normal joint examination | Referred pain | Consider alternative diagnosis |

Onset of pain and swelling over several hours or one to two days | Infection, crystal deposition disease, other inflammatory arthritic condition | CBC, ESR, uric acid level, arthrocentesis with evaluation for crystals |

Pain elicited by joint movements against resistance only | Tendinitis, bursitis | MRI or ultrasonography if diagnosis in question |

Previous acute attacks in any joint with spontaneous resolution | Crystal deposition disease, other inflammatory arthritic condition | CBC, ESR, uric acid level, arthrocentesis with evaluation for crystals |

Prolonged course of corticosteroid therapy | Infection, avascular necrosis | CBC, ESR, arthrocentesis for cell count and cultures if concern for infection, radiography and possible MRI if considering avascular necrosis |

Psoriatic skin plaques, nail pitting, dactylitis | Psoriatic arthritis | CBC, ESR, arthrocentesis, HLA-B27 testing, ANA testing; none of these tests are diagnostic but can exclude other conditions |

Restricted active and passive range of motion | Intra-articular pathology | Radiography and/or MRI if indicated |

Sudden onset of pain in seconds or minutes | Fracture, internal derangement, trauma, loose body | Radiography |

Urethritis, conjunctivitis, diarrhea, rash, sacroiliitis | Reactive arthritis | CBC; ESR; arthrocentesis; HLA-B27 testing; urine PCR testing for Chlamydia trachomatis; stool cultures for Salmonella, Shigella, and Campylobacter |

Young adult, migratory polyarthralgias, tendons inflamed | Gonococcal arthritis | Urine PCR testing, blood culture, and synovial fluid analysis for Neisseria gonorrhoeae |

Abbreviations: ACE = angiotensin-converting enzyme; ANA = antinuclear antibodies; CBC = complete blood count; ESR = erythrocyte sedimentation rate; MRI = magnetic resonance imaging; PCR = polymerase chain reaction.

[Source 2 ]Physical examination

The physical examination should focus on the involved and contralateral joints, the surrounding area, possible systemic manifestations, or polyarticular involvement 4. The first step is to confirm that the joint pain is truly localized and not a periarticular process, such as tendinitis, bursitis, or cellulitis 1. The presence of a joint effusion signifies intra-articular pathology, with patients typically reporting painful limitation of active and passive joint motion 1.

A diagnosis of osteoarthritis can often be based on the history and physical examination 4. The characteristic presentation includes painful and limited range of motion, crepitus, effusions, instability, or deformities 14. Heberden and Bouchard nodes are pathognomonic for osteoarthritis. They result from hard, bony thickening that gradually forms around the distal and proximal interphalangeal joints of the fingers, respectively 13. The first carpometacarpal joint is one of the most common sites of osteoarthritis 13.

Inflammatory arthritis elicits painful range of motion and erythema that is typically confined to the affected joint. Gout can present with intense erythema of the skin. It is often confused with cellulitis because this finding may extend past the joint margin 8.

There are many superficial examination findings that can suggest specific diagnoses. Subcutaneous nodules (tophi) and podagra (gouty arthritis of the first metatarsophalangeal joint) are highly specific for gout 13. Erythema nodosum may be a manifestation of sarcoidosis or inflammatory bowel disease; psoriatic skin plaques are associated with psoriatic arthritis; and oral ulcers can indicate reactive arthritis or Behçet syndrome 1. The presence of a joint effusion signifies intra-articular pathology, with patients typically reporting painful limitation of active and passive joint motion 1.

Septic arthritis is most likely to seed within a larger joint 1. The presence of a joint effusion signifies intra-articular pathology, with patients typically reporting painful limitation of active and passive joint motion 1 and to be accompanied by erythema, warmth, and immobility 11. Although clinical manifestations have low sensitivity 11, acute monoarthritis with fever should be considered to have a bacterial etiology until proven otherwise because of the potential consequences of inadequate treatment.20 For example, morbidity associated with septic arthritis includes functional deterioration, arthrodesis, and amputation11,12; the mortality rate is 10% to 20% 11.

Diagnostic tests

Because the causes of acute monoarthritis vary widely, a stepwise approach to diagnosis can aid decision making (Figure 1) 15. In the setting of trauma, radiography of the affected joint is required to rule out dislocation or fracture before performing active physical examination maneuvers 1. Radiography can also show signs of osteoarthritis, such as joint space narrowing, osteophytes, and subchondral sclerosis 1. If a joint effusion is present in the absence of traumatic injury, arthrocentesis should be performed, particularly when other inflammatory signs are present and there is a reasonable concern for infection (e.g., fever, erythema, warmth) 1.

Analysis of synovial fluid distinguishes infectious and inflammatory causes of acute monoarthritis (e.g., rheumatoid, septic, and crystal-induced arthritis) from non-inflammatory causes (e.g., trauma, osteoarthritis) 7. Analysis should include cell count and differential, white blood cell count, Gram stain, cultures, and crystal evaluation 7.

Many cases of acute gouty arthritis are diagnosed without synovial fluid analysis 16. To improve the predictive value of clinical diagnosis, a gout calculator has been developed 17. Seven predictive variables are included in this rule, and a scoring system has been developed to guide the decision to treat the patient for gout, pursue synovial fluid analysis, or search for other causes 18. A complete blood count and uric acid level can also aid in the diagnosis, especially if synovial fluid cannot be successfully obtained 19.

A synovial fluid white blood cell count greater than 50,000 per mm³ (50.0 × 109 per L) with at least 90% neutrophils is the most useful laboratory finding for making an early diagnosis of septic arthritis 4. This traditional cutoff lacks sensitivity because there can be wide overlap with inflammatory conditions, but higher white blood cell counts in the synovial fluid have a greater association with septic arthritis 20. Staphylococci and streptococci are the most common bacterial causes at 40% and 28%, respectively, and their presence may suggest drug abuse. These organisms are also associated with cellulitis, endocarditis, and chronic osteomyelitis 11.

Gram-stain results should guide initial antibiotic choice. Gram-negative organisms account for 10% to 21% of cases of septic arthritis 11. Mycobacterial and fungal arthritis typically present in immunocompromised patients, and Lyme arthritis often presents as a late manifestation of Lyme disease 11. Special consideration should be given to patients with prosthetic joint infection because the cutoff values for infection may be as low as 1,100 white blood cells per mm³ (1.1 × 109 per L), with a neutrophil differentiation greater than 65% 4. Gonococci are cultured from joints in fewer than 50% of cases of gonococcal arthritis1 21; therefore, it is often necessary to obtain cultures from appropriate mucosal sites of infection 21. Noninflammatory synovial fluid (less than 2,000 cells per mm3 [2.0 × 109 per L]) is suggestive of osteoarthritis or internal derangement.1 Inflammatory synovial fluid containing monosodium urate crystals is highly suggestive of gout, particularly in the presence of podagra; however, the absence of crystals does not exclude crystal-induced arthritis, such as pseudogout 17.

Erythrocyte sedimentation rate and C-reactive protein level are often elevated in inflammatory conditions 19. Literature comparing these two values is limited; however, it has been determined that these tests are more useful for following a disease course than discriminating the presence or absence of the disease 19.

Table 2. Diagnostic rule for gout when synovial fluid analysis is unavailable

Patient with monoarthritis | ||

Male sex | 2 points | |

Previous patient-reported arthritis attack | 2 points | |

Onset within 1 day | 0.5 point | |

Joint redness | 1 point | |

Involvement of first metatarsophalangeal joint | 2.5 points | |

Hypertension or ≥ 1 cardiovascular diseases* | 1.5 points | |

Serum uric acid > 5.88 mg per dL (350 μmol per L) | 3.5 points | |

Total score: | ________ | |

≤ 4 points | > 4 and < 8 points | ≥ 8 points |

Non-gout in 95% | Uncertain diagnosis | Gout in 87% |

Consider alternative diagnosis, such as calcium pyrophosphate dihydrate deposition disease arthritis, reactive arthritis, septic arthritis, rheumatoid arthritis, osteoarthritis, or psoriatic arthritis | Perform arthrocentesis and analysis with polarization microscopy for the presence of crystals; if not possible or available, then extensive follow-up of the patient | Manage the patient as having gout, including care for cardiovascular risk |

Footnote: *Indicates angina pectoris, myocardial infarction, heart failure, cerebrovascular accident, transient ischemic attack, or peripheral vascular disease.

Monoarthritis treatment

Monoarthritis treatment involves treating the underlying cause.

References- Gorn AH, Brahn E. Monoarticular arthritis (diagnostic approach). Essential Evidence Plus; 2015.

- Acute Monoarthritis: Diagnosis in Adults. Am Fam Physician. 2016 Nov 15;94(10):810-816. https://www.aafp.org/afp/2016/1115/p810.html

- Mathews CJ, Weston VC, Jones A, Field M, Coakley G. Bacterial septic arthritis in adults. Lancet. 2010;375(9717):846–855.

- Ma L, Cranney A, Holroyd-Leduc JM. Acute monoarthritis: what is the cause of my patient’s painful swollen joint? CMAJ. 2009;180(1):59–65.

- Freed JF, Nies KM, Boyer RS, Louie JS. Acute monoarticular arthritis. A diagnostic approach. JAMA. 1980;243:2314–6.

- Manek NJ, Lane NE. Osteoarthritis: current concepts in diagnosis and management. Am Fam Physician. 2000;61(6):1795–1804.

- Margaretten ME, Kohlwes J, Moore D, Bent S. Does this adult patient have septic arthritis? JAMA. 2007;297(13):1478–1488.

- Hainer BL, Matheson E, Wilkes RT. Diagnosis, treatment, and prevention of gout. Am Fam Physician. 2014;90(12):831–836.

- Schlesinger N, Thiele RG. The pathogenesis of bone erosions in gouty arthritis. Ann Rheum Dis. 2010;69(11):1907–1912.

- Goldenberg DL. Septic arthritis. Lancet. 1998;351(9097):197–202.

- Horowitz DL, Katzap E, Horowitz S, Barilla-LaBarca ML. Approach to septic arthritis. Am Fam Physician. 2011;84(6):653–660.

- Ross JJ, Saltzman CL, Carling P, Shapiro DS. Pneumococcal septic arthritis: review of 190 cases. Clin Infect Dis. 2003;36(3):319–327.

- Luosujärvi R. Disease-specific signs and symptoms in patients with inflammatory joint diseases. Essential Evidence Plus; 2013.

- Sinusas K. Osteoarthritis: diagnosis and treatment [published correction appears in Am Fam Physician. 2012;86(10):893]. Am Fam Physician. 2012;85(1):49–56.

- Siva C, Velazquez C, Mody A, Brasington R. Diagnosing acute monoarthritis in adults: a practical approach for the family physician. Am Fam Physician. 2003;68(1):83–90.

- Janssens HJ, Fransen J, van de Lisdonk EH, van Riel PL, van Weel C, Janssen M. A diagnostic rule for acute gouty arthritis in primary care without joint fluid analysis. Arch Intern Med. 2010;170(13):1120–1126.

- Kienhorst LB, Janssens HJ, Fransen J, Janssen M; British Society for Rheumatology. The validation of a diagnostic rule for gout without joint fluid analysis: a prospective study. Rheumatology (Oxford). 2015;54(4):609–614.

- Krishnan E, Svendsen K, Neaton JD, Grandits G, Kuller LH; MRFIT Research Group. Long-term cardiovascular mortality among middle-aged men with gout. Arch Intern Med. 2008;168(10):1104–1110.

- Waits JB. Rational use of laboratory testing in the initial evaluation of soft tissue and joint complaints. Prim Care. 2010;37(4):673–689, v.

- Li SF, Henderson J, Dickman E, Darzynkiewicz R. Laboratory tests in adults with monoarticular arthritis: can they rule out a septic joint? Acad Emerg Med. 2004;11(3):276–280.

- Bardin T. Gonococcal arthritis. Best Pract Res Clin Rheumatol. 2003;17(2):201–208.