Myofascial trigger points

Myofascial trigger points are hard, discrete, palpable nodules in a taut band of skeletal muscle which is palpable and tender during physical examination, that may be spontaneously painful (i.e. active), or painful only on compression (i.e. latent) 1. Myofascial trigger points produce pain locally and in a referred pattern and often accompany chronic musculoskeletal disorders. The spots are painful on compression and can produce referred pain, referred tenderness, motor dysfunction, and autonomic phenomena 2.

Myofascial trigger points are classified as being active or latent, depending on their clinical characteristics 3. An active myofascial trigger point causes pain at rest and is clinically associated with spontaneous pain in the immediate surrounding tissue and/or to distant sites in specific referred pain patterns. Strong digital pressure on the active myofascial trigger point exacerbates the patient’s spontaneous pain complaint and mimics the patient’s familiar pain experience. Myofascial trigger points can also be classified as latent, in which case the myofascial trigger point is physically present but not associated with a spontaneous pain complaint and may restrict movement or cause muscle weakness 4. However, patient presenting with muscle restrictions or weakness may become aware of pain originating from a latent latent myofascial trigger point only when pressure is applied directly over the point at the site of the nodule 5. Both latent and active myofascial trigger points can be associated with muscle dysfunction, muscle weakness, and a limited range of motion. Over the years, the necessity of the physical presence of myofascial trigger points for the definition of myofascial pain syndrome has been hotly debated 1.

Myofascial trigger point is tender to palpation with a referred pain pattern that is similar to the patient’s pain complaint 6. This referred pain is felt not at the site of the trigger-point origin, but remote from it. The pain is often described as spreading or radiating 7. Referred pain is an important characteristic of a trigger point. It differentiates a trigger point from a tender point, which is associated with pain at the site of palpation only (Table 1) 8.

Moreover, when firm pressure is applied over the trigger point in a snapping fashion perpendicular to the muscle, a “local twitch response” is often elicited 9. A local twitch response is defined as a transient visible or palpable contraction or dimpling of the muscle and skin as the tense muscle fibers (taut band) of the trigger point contract when pressure is applied. This response is elicited by a sudden change of pressure on the trigger point by needle penetration into the trigger point or by transverse snapping palpation of the trigger point across the direction of the taut band of muscle fibers. Thus, a classic trigger point is defined as the presence of discrete focal tenderness located in a palpable taut band of skeletal muscle, which produces both referred regional pain (zone of reference) and a local twitch response. Trigger points help define myofascial pain syndromes.

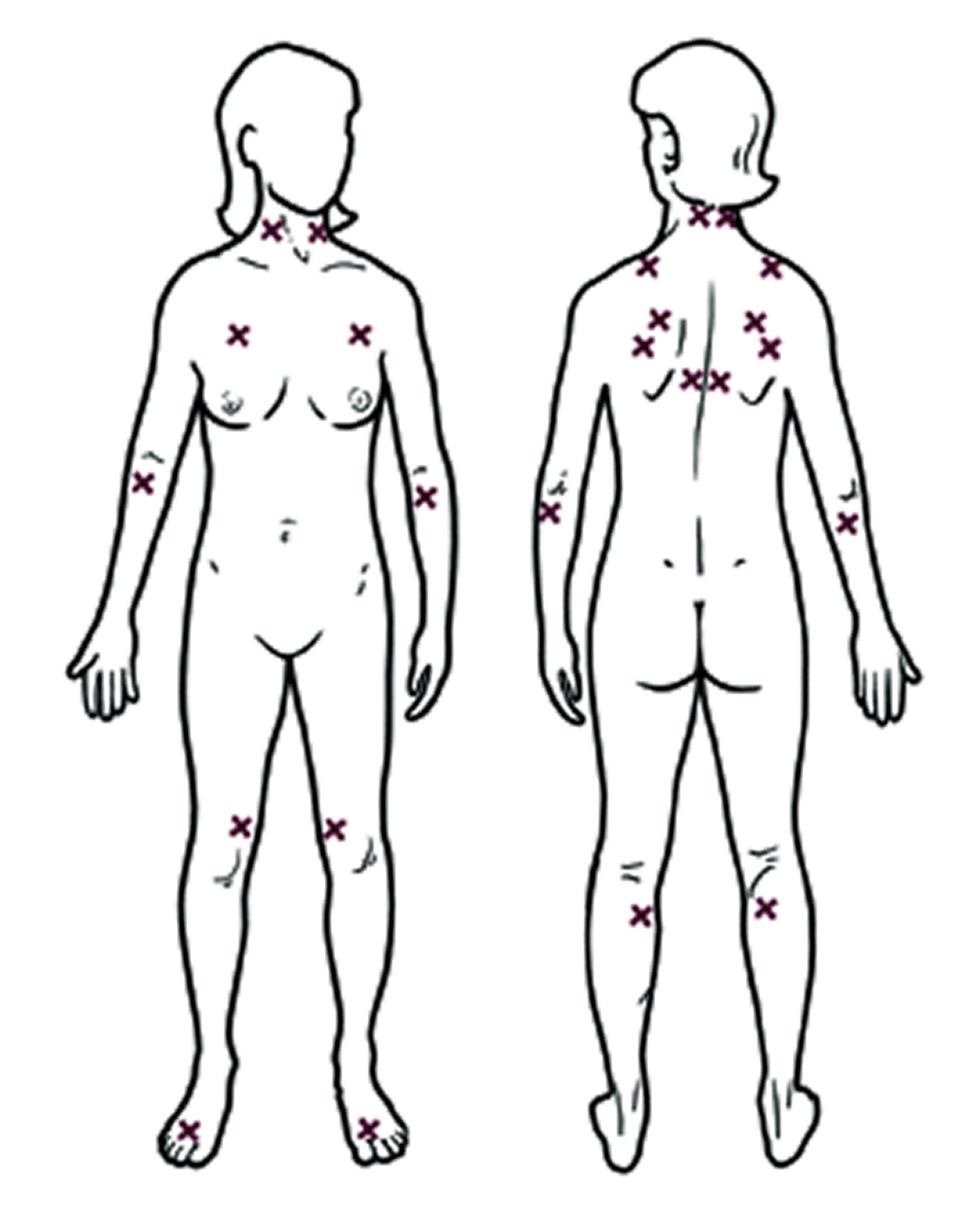

Tender points, by comparison, are associated with pain at the site of palpation only, are not associated with referred pain, and occur in the insertion zone of muscles, not in taut bands in the muscle belly 8. Patients with fibromyalgia have tender points by definition. Concomitantly, patients may also have myofascial trigger points with myofascial pain syndrome. Thus, these two pain syndromes may overlap in symptoms and be difficult to differentiate without a thorough examination by a skilled physician.

The diagnostic criteria for myofascial trigger points are under debate, but there are three minimum clinical diagnostic criteria (1–3) and six confirmatory criteria (4–9) 10:

- Presence of a palpable taut band within a skeletal muscle

- Presence of a hypersensitive spot within the taut band

- Reproduction of a referred pain sensation with stimulation of the spot

- Presence of a local twitch response with snapping palpation of the taut band

- Presence of a jump sign

- Patient recognition of the elicited pain

- Predicted referred pain patterns

- Muscle weakness or muscle tightness

- Pain with stretching or contraction of the affected muscle

Table 1. Myofascial Trigger points versus Tender points

| Myofascial trigger points | Tender points |

|---|---|

Local tenderness, taut band, local twitch response, jump sign | Local tenderness |

Singular or multiple | Multiple |

May occur in any skeletal muscle | Occur in specific locations that are symmetrically located |

May cause a specific referred pain pattern | Do not cause referred pain, but often cause a total body increase in pain sensitivity |

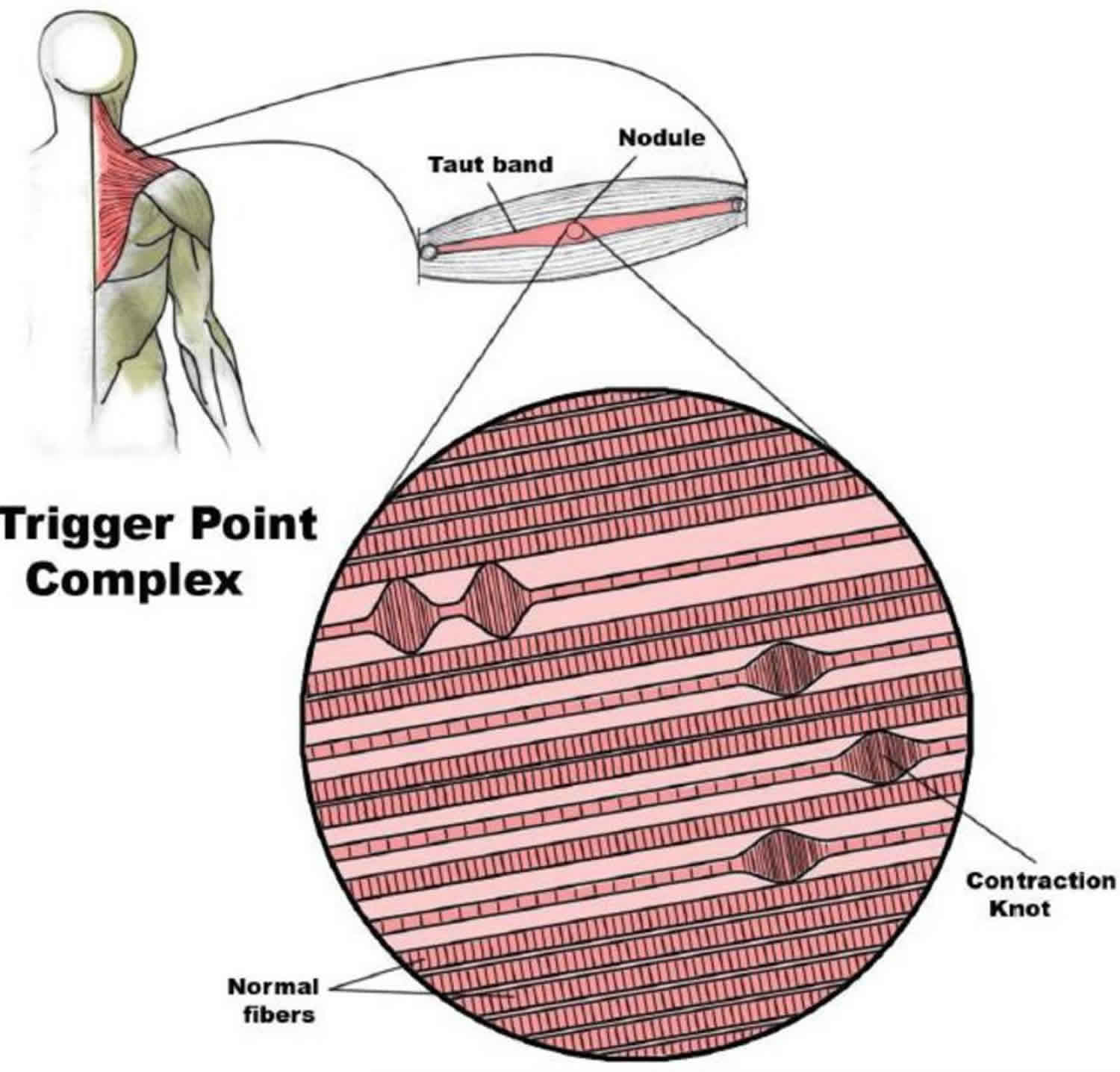

Figure 1. Myofascial trigger point complex

Footnote: Schematic of a trigger point complex. A trigger point complex in a taut band of muscle is composed of multiple contraction knots.

[Source 1 ]Although the myofascial trigger point is a common physical finding, it is often an overlooked component of non-articular musculoskeletal pain because its pathophysiology is not fully understood. Besides the use of palpation, there are currently no accepted criteria (e.g., biomarkers, electrodiagnostic testing, imaging, etc.) for identifying or quantitatively describing myofascial trigger points. In addition, diagnostic criteria are imprecise, and the full impact of myofascial pain syndrome on life activity and function is not fully understood. To complicate this issue further, myofascial trigger points are associated clinically with a variety of medical conditions including those of metabolic, visceral, endocrine, infectious, and psychological origin13, and are prevalent across a wide range of musculoskeletal disorders. If the myofascial trigger point is frequently associated with other musculoskeletal pain syndromes, it would make this finding non-specific—if it is not, it would make the myofascial trigger point specific for myofascial pain syndrome.

Numerous clinicians over the past few centuries, from various countries and specialties, have encountered and described hard tender nodules in muscle. They have attempted to explain their cause, tissue properties, and relationship to myofascial pain syndrome. However, most investigations were hampered by a lack of objective diagnostic techniques that could record more than simply their presence or absence. As a result, theories of the myofascial trigger point pathogenesis, pathophysiology, and contribution to the diagnosis of myofascial pain syndrome have been speculative.

As previously mentioned, myofascial trigger points are found as discrete nodules within a taut band of skeletal muscle that may be spontaneously painful or painful only upon palpation. Although muscle pain displays unique clinical characteristics compared to cutaneous and neuropathic pain, the nature of the symptoms are highly dependent upon the individual’s perception of its characteristic qualities (e.g., boring, aching, sharp, etc.), intensity, distribution, and duration. The way in which individuals report their symptoms presents a challenge for standardization and validation if these are to be used as diagnostic criteria, outcome measures of improvement, and/or in clinical trials. Characteristics like the quality of the pain, its distribution, and whether it radiates, have never been required for the diagnosis of myofascial pain syndrome.

Some investigators are reluctant to diagnose myofascial pain syndrome without a palpable nodule and instead rely exclusively on self-reports. myofascial trigger points are central to the process, but are they necessary? Myofascial trigger points are commonly found in asymptomatic individuals. These latent myofascial trigger points are nodules with the same physical characteristics as active myofascial trigger points; however, palpation is required to elicit pain. In addition, some nodules are not tender to palpation (non-tender nodules) and may be found proximal to or remote from sites of pain. Although the term “myofascial pain syndrome” is commonly used and generally accepted, it does not resolve the clinical dilemma of soft tissue pain in which the palpable nodule is non-tender or no nodule is palpable (and is not explained by radiculopathy, muscle strain, etc.).

In Travell and Simons’ myofascial trigger point-centered model of myofascial pain, the diagnostic criteria and relevant clinical findings can only be studied descriptively, using patient-reported outcomes. Moreover, measurements are obtained via dichotomous data (e.g., presence or absence of pain; presence or absence of myofascial trigger point) or nominal data (i.e., no nodule vs. non-painful nodule vs. latent myofascial trigger point vs. active myofascial trigger point). Since there is a bias toward objective findings, the sine qua non for this syndrome is the spontaneously painful nodule (i.e., active myofascial trigger point). Unfortunately, the role of the nodule in this process has not been determined. It remains unknown whether the nodule is an associated finding, whether it is a causal or pathogenic element in myofascial pain syndrome, and whether or not its disappearance is essential for effective treatment.

In a survey conducted in 2000, the vast majority of American Pain Society members believed myofascial pain syndrome to be a distinct clinical entity, characterized by the finding of myofascial trigger points 11. A growing number of pain clinics are utilizing Travell’s pioneering techniques for the evaluation and treatment of muscle pain disorders. Nevertheless, the lack of consistent nomenclature, universally accepted diagnostic criteria, objective assessments, and conclusive biopsy findings has led to much controversy and generally poor acceptance by mainstream medicine.

Myofascial trigger points pathogenesis

There are several proposed histopathologic mechanisms to account for the development of myofascial trigger points and subsequent pain patterns, but scientific evidence is lacking. Many researchers agree that acute trauma or repetitive microtrauma may lead to the development of a trigger point. Lack of exercise, prolonged poor posture, vitamin deficiencies, sleep disturbances, and joint problems may all predispose to the development of micro-trauma 3. Occupational or recreational activities that produce repetitive stress on a specific muscle or muscle group commonly cause chronic stress in muscle fibers, leading to trigger points. Examples of predisposing activities include holding a telephone receiver between the ear and shoulder to free arms; prolonged bending over a table; sitting in chairs with poor back support, improper height of arm rests or none at all; and moving boxes using improper body mechanics 12.

Acute sports injuries caused by acute sprain or repetitive stress (e.g., pitcher’s or tennis elbow, golf shoulder), surgical scars, and tissues under tension frequently found after spinal surgery and hip replacement may also predispose a patient to the development of trigger points 13.

Myofascial trigger points signs and symptoms

Patients who have myofascial trigger points often report regional, persistent pain that usually results in a decreased range of motion of the muscle in question. Often, the muscles used to maintain body posture are affected, namely the muscles in the neck, shoulders, and pelvic girdle, including the upper trapezius, scalene, sternocleidomastoid, levator scapulae, and quadratus lumborum 14. Although the pain is usually related to muscle activity, it may be constant. It is reproducible and does not follow a dermatomal or nerve root distribution. Patients report few systemic symptoms, and associated signs such as joint swelling and neurologic deficits are generally absent on physical examination 15.

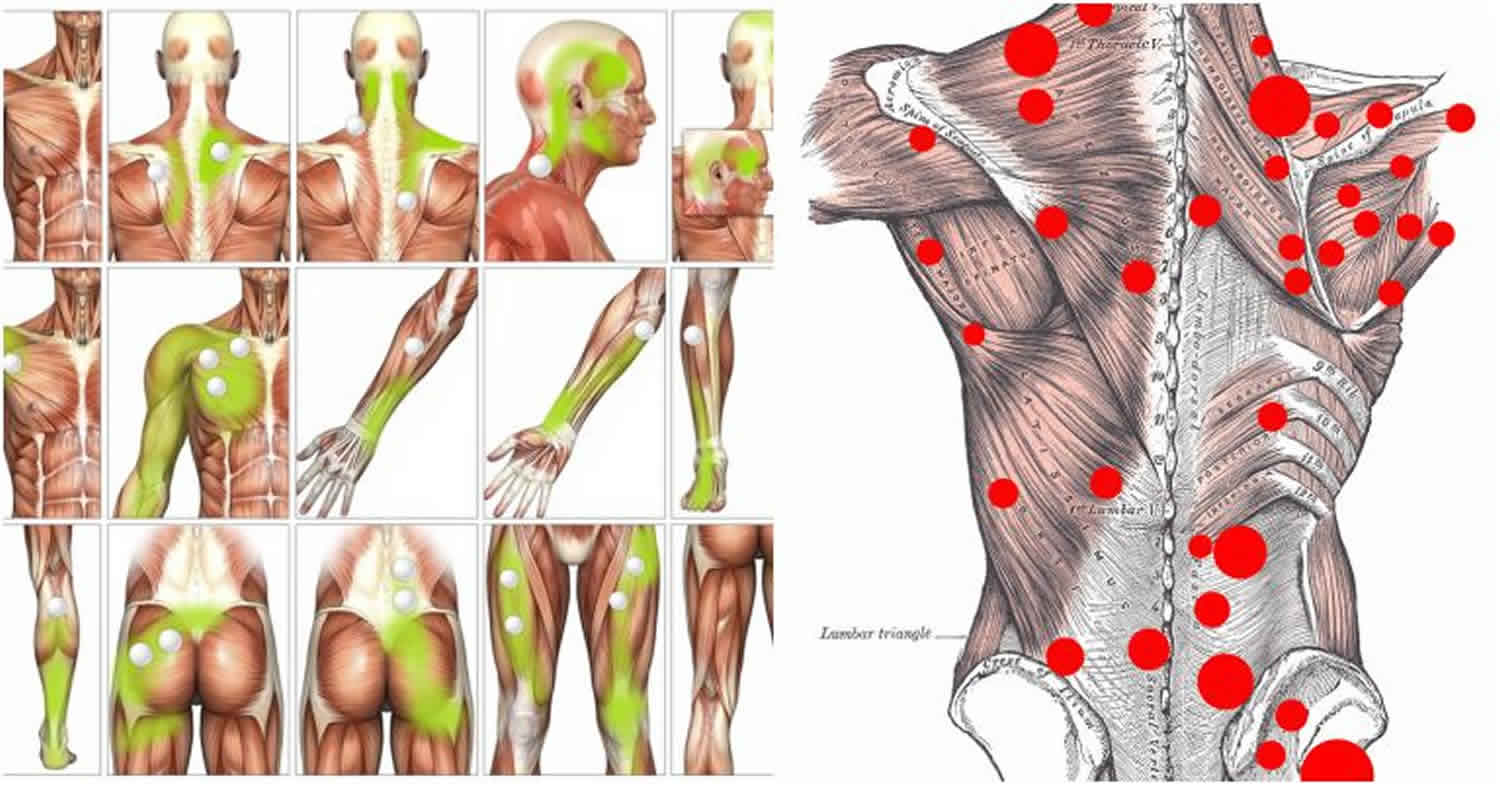

In the head and neck region, myofascial pain syndrome with trigger points can manifest as tension headache, tinnitus, temporomandibular joint pain, eye symptoms, and torticollis 16. Upper limb pain is often referred and pain in the shoulders may resemble visceral pain or mimic tendonitis and bursitis 17. In the lower extremities, trigger points may involve pain in the quadriceps and calf muscles and may lead to a limited range of motion in the knee and ankle. Trigger-point hypersensitivity in the gluteus maximus and gluteus medius often produces intense pain in the low back region 16. Examples of trigger-point locations are illustrated in Figure 2.

Figure 2. Trigger point chart

[Source 9 ]Figure 3. Most frequent locations of myofascial trigger points

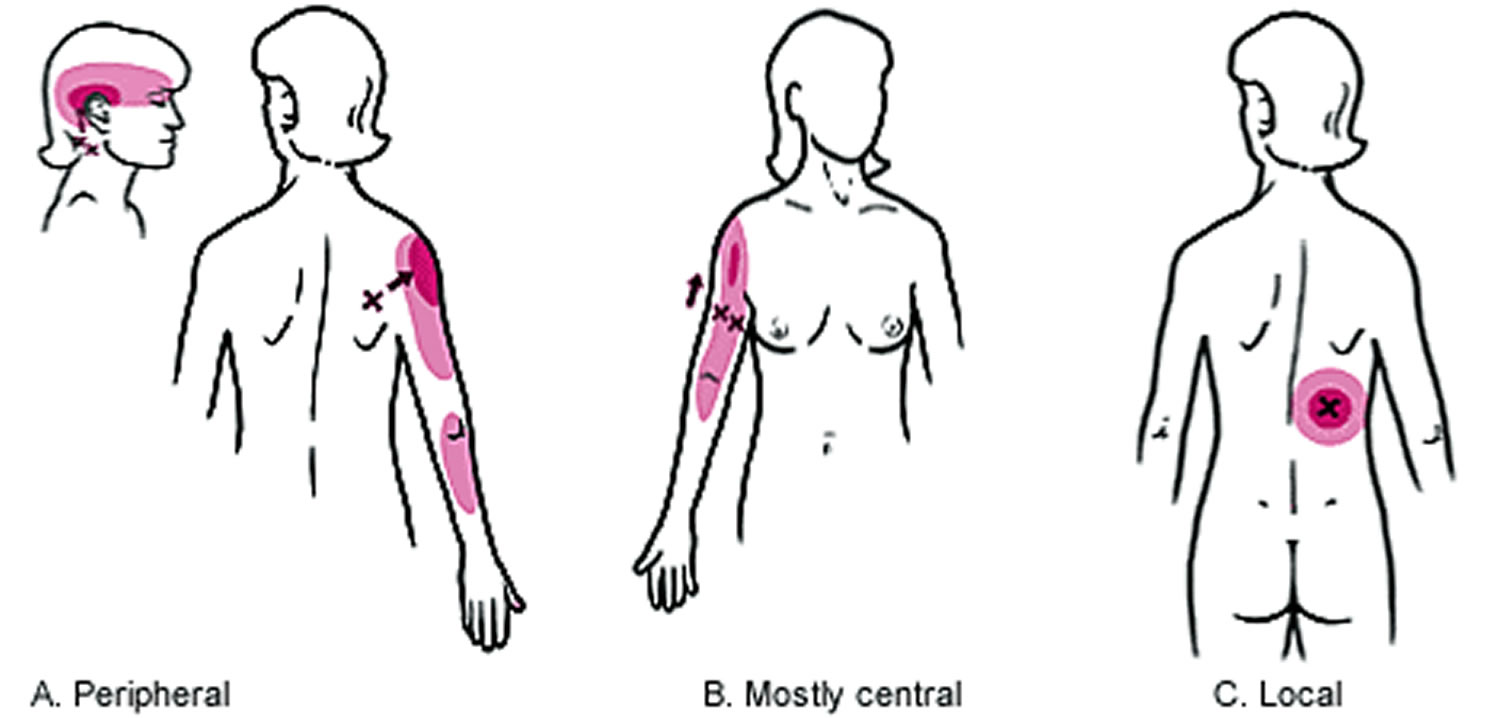

[Source 17 ]Figure 4. Directions in which trigger points may refer pain

Footnote: Examples of the three directions in which trigger points (Xs) may refer pain (red). (A) Peripheral projection of pain from suboccipital and infraspinatus trigger points. (B) Mostly central projection of pain from biceps brachii trigger points with some pain in the region of the distal tendinous attachment of the muscle. (C) Local pain from a trigger point in the serratus posterior inferior muscle.

[Source 9 ]Myofascial trigger points diagnosis

Palpation of a hypersensitive bundle or nodule of muscle fiber of harder than normal consistency is the physical finding most often associated with a trigger point 9. Localization of a trigger point is based on the physician’s sense of feel, assisted by patient expressions of pain and by visual and palpable observations of local twitch response 9. This palpation will elicit pain over the palpated muscle and/or cause radiation of pain toward the zone of reference in addition to a twitch response. The commonly encountered locations of trigger points and their pain reference zones are consistent 8. Many of these sites and zones of referred pain have been illustrated in Figure 4 9.

No laboratory test or imaging technique has been established for diagnosing trigger points 5. However, the use of ultrasonography, electromyography, thermography, and muscle biopsy has been studied.

Myofascial trigger point therapy

Predisposing and perpetuating factors in chronic overuse or stress injury on muscles must be eliminated, if possible 18. Pharmacologic treatment of patients with chronic musculoskeletal pain includes analgesics and medications to induce sleep and relax muscles. Antidepressants, neuroleptics, or nonsteroidal anti-inflammatory drugs are often prescribed for these patients 19.

Nonpharmacologic treatment modalities include acupuncture, osteopathic manual medicine techniques, massage, acupressure, ultrasonography, application of heat or ice, diathermy, transcutaneous electrical nerve stimulation, ethyl chloride Spray and Stretch technique, dry needling, and trigger-point injections with local anesthetic, saline, or steroid. The long-term clinical efficacy of various therapies is not clear, because data that incorporate pre- and post-treatment assessments with control groups are not available.

The Spray and Stretch technique involves passively stretching the target muscle while simultaneously applying dichlorodifluoromethane-trichloromonofluoromethane (Fluori-Methane) or ethyl chloride spray topically 3. The sudden drop in skin temperature is thought to produce temporary anesthesia by blocking the spinal stretch reflex and the sensation of pain at a higher center 9. The decreased pain sensation allows the muscle to be passively stretched toward normal length, which then helps to inactivate trigger points, relieve muscle spasm, and reduce referred pain 3.

Dichlorodifluoromethane-trichloromono-fluoromethane is a nontoxic, nonflammable vapor coolant spray that does not irritate the skin but is no longer commercially available for other purposes because of its effect in reducing the ozone layer. However, its use is safer for both patient and physician than the original volatile vapor coolant, ethyl chloride. Ethyl chloride is a rapid-acting general anesthetic that becomes flammable and explosive when 4 to 15 percent of the vapor is mixed with air 9. Nevertheless, ethyl chloride remains a popular agent because of its local anesthetic action and its greater cooling effect than that of dichlorodifluoromethane-trichloromonofluoromethane 3.

The decision to treat trigger points by manual methods or by injection depends strongly on the training and skill of the physician as well as the nature of the trigger point itself 9. For trigger points in the acute stage of formation (before additional pathologic changes develop), effective treatment may be delivered through physical therapy. Furthermore, manual methods are indicated for patients who have an extreme fear of needles or when the trigger point is in the middle of a muscle belly not easily accessible by injection (i.e., psoas and iliacus muscles) 9. The goal of manual therapy is to train the patient to effectively self-manage the pain and dysfunction. However, manual methods are more likely to require several treatments and the benefits may not be as fully apparent for a day or two when compared with injection 9.

While relatively few controlled studies on trigger-point injection have been conducted, trigger-point injection and dry needling of trigger points have become widely accepted. This therapeutic approach is one of the most effective treatment options available and is cited repeatedly as a way to achieve the best results 3.

Trigger-point injection is indicated for patients who have symptomatic active trigger points that produce a twitch response to pressure and create a pattern of referred pain. In comparative studies 20, dry needling was found to be as effective as injecting an anesthetic solution such as procaine (Novocain) or lidocaine (Xylocaine) 9. However, post-injection soreness resulting from dry needling was found to be more intense and of longer duration than the soreness experienced by patients injected with lidocaine 9.

One noncontrolled study 20 comparing the use of dry needling versus injection of lidocaine to treat trigger points showed that 58 percent of patients reported complete relief of pain immediately after trigger-point injection and the remaining 42 percent of patients claimed that their pain was minimal (1–2/10) on the pain scale. Both dry needling and injection with 0.5 percent lidocaine were equally successful in reducing myofascial pain. Postinjection soreness, a different entity than myofascial pain, often developed, especially after use of the dry needling technique 20. These results support the opinion of most researchers that the critical therapeutic factor in both dry needling and injection is mechanical disruption by the needle 9.

Among the invasive therapies, the scientific articles report mixed results. Generally, dry needling, anesthetic injection, steroids, and botulinum toxin-A (Botox) of the trigger point have all been shown to provide pain relief 21. Regardless of the method used, there is considerable agreement that elicitation of a local twitch response produces more immediate and long-lasting pain relief than no elicitation of local twitch response 22, although some still believe that eliciting a local twitch response is not necessary for improvement. Nevertheless, within minutes of a single induced local twitch response, Shah et al. 23 found that the initially elevated levels of substance P and calcitonin gene-related peptide within the active myofascial trigger point in the upper trapezius muscle decreased to levels approaching that of normal, uninvolved muscle tissue. Though the mechanism of an local twitch response is unknown, the reduction of these biochemicals in the local muscle area may be due to a small, localized increase in blood flow and/or nociceptor and mechanistic changes associated with an augmented inflammatory response 24.

While treatment options for soft tissue pain have not changed dramatically, researchers today have certainly discovered better ways of categorizing and analyzing the clinical data they collect and determining if a treatment is effective. For example, since Travell and Simons’ time, researchers have begun to utilize classifications such as latent, “non-painful palpable,” and “painful, but no nodule” to categorize myofascial pain syndrome. Gerber et al. 25 have also begun to assess the effect of treatment on other aspects besides pain such as quality of life and function, disability, sleep, mood, and range of motion. Clinicians are shifting the focus from not only pain relief and increasing function, but to improving the patient’s quality of life as well.

Though many practitioners can attest to improvement in pain levels of myofascial pain syndrome, it is measured using self-reports of pain levels pre- and post-treatment. To date, the number of randomized, placebo-controlled trials is few, and most of them have small numbers of participants 1. Additionally, because they rely exclusively on self-reports, there remains uncertainty about the validity of the findings. Thus, while a variety of pharmacological and nonpharmacological treatments have shown efficacy, studies of proper size and quantitative outcome measures need to be performed.

References- Shah JP, Thaker N, Heimur J, Aredo JV, Sikdar S, Gerber L. Myofascial Trigger Points Then and Now: A Historical and Scientific Perspective. PM R. 2015;7(7):746–761. doi:10.1016/j.pmrj.2015.01.024 https://www.ncbi.nlm.nih.gov/pmc/articles/PMC4508225

- Simons DG, Travell JG, Simons LS. Travell & Simons’ Myofascial pain and dysfunction: the trigger point manual. 2d ed. Baltimore: Williams & Wilkins, 1999:5.

- Han SC, Harrison P. Myofascial pain syndrome and trigger-point management. Reg Anesth. 1997;22:89–101.

- Ling FW, Slocumb JC. Use of trigger point injections in chronic pelvic pain. Obstet Gynecol Clin North Am. 1993;20:809–15.

- Fricton JR, Kroening R, Haley D, Siegert R. Myofascial pain syndrome of the head and neck: a review of clinical characteristics of 164 patients. Oral Surg Oral Med Oral Pathol. 1985;60:615–23.

- Hong CZ, Hsueh TC. Difference in pain relief after trigger point injections in myofascial pain patients with and without fibromyalgia. Arch Phys Med Rehabil. 1996;77:1161–6.

- Mense S, Schmit RF. Muscle pain: which receptors are responsible for the transmission of noxious stimuli? In: Rose FC, ed. Physiological aspects of clinical neurology. Oxford: Blackwell Scientific Publications, 1977:265–78.

- Hopwood MB, Abram SE. Factors associated with failure of trigger point injections. Clin J Pain. 1994;10:227–34.

- Simons DG, Travell JG, Simons LS. Travell & Simons’ Myofascial pain and dysfunction: the trigger point manual. 2d ed. Baltimore: Williams & Wilkins, 1999:94–173.

- Myofascial Pain. Global Year Against Musculoskeletal Pain Oct 2009 – Oct 2010. http://s3.amazonaws.com/rdcms-iasp/files/production/public/Content/ContentFolders/GlobalYearAgainstPain2/MusculoskeletalPainFactSheets/MyofascialPain_Final.pdf

- Signs and symptoms of the myofascial pain syndrome: a national survey of pain management providers. Harden RN, Bruehl SP, Gass S, Niemiec C, Barbick B. Clin J Pain. 2000 Mar; 16(1):64-72.

- Rachlin ES. Trigger points. In: Rachlin ES, ed. Myofascial pain and fibromyalgia: trigger point management. St. Louis: Mosby, 1994:145–57.

- Fischer AA. Injection techniques in the management of local pain. J Back Musculoskeletal Rehabil. 1996;7:107–17.

- Simons DG, Travell JG, Simons LS. Travell & Simons’ Myofascial pain and dysfunction: the trigger point manual. 2d ed. Baltimore: Williams & Wilkins, 1999:11–93.

- Yunus MB. Fibromyalgia syndrome and myofascial pain syndrome: clinical features, laboratory tests, diagnosis, and pathophysiologic mechanisms. In: Rachlin ES, ed. Myofascial pain and fibromyalgia: trigger point management. St. Louis: Mosby, 1994:3–29.

- Sola AE, Bonica JJ. Myofascial pain syndromes. In: Bonica JJ, ed. The management of pain. 2d ed. Philadelphia: Lea & Febiger, 1990:352–67.

- Rachlin ES. History and physical examination for regional myofascial pain syndrome. In: Rachlin ES, ed. Myofascial pain and fibromyalgia: trigger point management. St. Louis: Mosby, 1994:159–72.

- Trigger Points: Diagnosis and Management. Am Fam Physician. 2002 Feb 15;65(4):653-661. https://www.aafp.org/afp/2002/0215/p653.html

- Imamura ST, Fischer AA, Imamura M, Teixeira MJ, Tchia Yeng Lin, Kaziyama HS, et al. Pain management using myofascial approach when other treatment failed. Phys Med Rehabil Clin North Am. 1997;8:179–96.

- Hong CZ. Lidocaine injection versus dry needling to myofascial trigger point. The importance of the local twitch response. Am J Phys Med Rehabil. 1994;73:256–63.

- Majlesi J, Unalan H. Effect of treatment on trigger points. Curr Pain Headache Rep. 2010 Oct;14(5):353–360.

- Lartigue A. Patient education and self-advocacy. Myofascial pain syndrome: treatments. J Pain Palliat Care Pharmacother. 2009;23:169–170.

- Shah JP, Danoff JV, Desai MJ, et al. Biochemicals associated with pain and inflammation are elevated in sites near to and remote from active myofascial trigger points. Arch Phys Med Rehabil. 2008 Jan;89(1):16–23.

- Willard F. Integrative Pain Medicine: The Science and Practice of Complementary and Alternative Medicine in Pain Management. Humana Press Inc; Totowa: 2008. Basic Mechanisms of Pain.” Future Trends in CAM Research.

- Gerber LH, Sikdar S, Armstrong K, et al. A systematic comparison between subjects with no pain and pain associated with active myofascial trigger points. PM R. 2013 Nov;5(11):931–938.