Neuromyotonia

Acquired neuromyotonia also called Isaacs’ syndrome, continuous muscle fiber activity syndrome or Isaacs-Mertens syndrome, is a very rare neuromuscular disorder that causes spontaneous, continuous muscle activity of peripheral nerve origin that cannot be controlled, even during sleep or under general anesthesia. Neuromyotonia is a peripheral nerve hyperexcitability syndrome and a type of acquired channel disease 1.

Neuromyotonia often affects the muscles in the arms and legs, but may affect the whole body. Neuromyotonia is characterized clinically by muscle twitching at rest (visible myokymia), cramps that can be triggered by voluntary or induced muscle contraction, and impaired muscle relaxation (pseudomyotonia) 2. Often, patients also have symptoms of excessive sweating (hyperhidrosis), increased skin temperature, rapid heartbeats (tachycardia), problems with chewing, swallowing, speech, breathing and more rarely mild muscular weakness, and paresthesia. The disorder often gets worse over time. Neuromyotonia usually occurs in people aged 15 to 60 years, with most people experiencing symptoms before age 40. It may occur with certain types of cancer and is sometimes inherited.

The main clinical features of neuromyotonia 2:

- Muscle twitching

- Muscle cramps

- Muscle stiffness

- Muscle hypertrophy

- Pseudomyotonia

- Muscle weakness rarely

- Increased sweating

Although the exact underlying cause is unknown, there appear to be hereditary and acquired (non-inherited) forms of neuromyotonia. Approximately 20% of affected individuals have a tumor of the thymus gland (thymoma). The thymus glands are the source of a number of specialized cells associated with autoimmune functions. The disorder is also associated with peripheral neuropathies and autoimmune diseases including myasthenia gravis in some individuals. It has also been reported following infections and radiation therapy.

Treatment is based on the signs and symptoms present in each person 3. Anticonvulsants, including phenytoin and carbamazepine, usually provide significant relief from the stiffness, muscle spasms, and pain associated with Isaacs’ syndrome. Plasma exchange may provide short-term relief for individuals with some forms of the acquired disorder.

Neuromyotonia causes

The exact cause of neuromyotonia is poorly understood. There appear to be hereditary and acquired (non-inherited) forms of neuromyotonia. Acquired neuromyotonia is an autoimmune disease in which the immune system malfunctions so that it damages parts of your body. The acquired neuromyotonia are often associated with malignancies, peripheral neuropathies, and a variety of autoimmune disorders of the nervous system. It was thought that neuromyotonia is an autoimmune disease because plasmapheresis is an effective method to treat the symptoms 4. Approximately 40% of affected individuals have antibodies that target the presynaptic voltage-gated potassium channels (VGKC’s) that affect the points at which the signals from the nerve fiber meet the muscle cell (neuromuscular junction), inducing hyperexcitability of peripheral nerves 1.

Since the first reports of acquired neuromyotonia or Issacs’ syndrome in 1961 5, thymoma, myasthenia gravis, vitiligo, Hashimoto’s thyroiditis, penicillamine treatment and anti-acetylcholine receptor disorder have been reported to be associated with neuromyotonia 6. In addition, neuromyotonia has been reported in patients with lung cancer, raising the possibility that tumor antigenic determinants are perhaps capable of triggering an autoimmune response producing antibodies that cross-react with neuronal voltage-gated ion channels.

Clinical associations of neuromyotonia 2:

- Autoantibody-mediated or autoimmune-associated

- Paraneoplastic

- Thymoma with or without myasthenia gravis

- Small cell lung carcinoma

- Lymphoma (Hodgkin’s)

- Plasmacytoma with IgM paraproteinaemia

- Associated with other autoimmune disorders

- Myasthenia gravis without thymoma

- Diabetes mellitus (insulin or noninsulin dependent)

- Chronic infl ammatory demyelinating neuropathy

- Guillain–Barré syndrome

- Addison’s disease

- Amyloidosis

- Celiac disease

- Hypothyroidism

- Penicillamine-induced in patients with rheumatoid disease

- Rheumatoid disease

- Systemic lupus erythematosus

- Systemic sclerosis

- Vitiligo

- Paraneoplastic

- Non-immune mediated

- Anterior horn cell degeneration (as part of motor neuron disease)

- Drugs: gold

- Genetic: hereditary neuropathy

- Idiopathic peripheral neuropathy

- Infective: staphylococcal infection

- Toxins: herbicide, insecticide, toluene, alcohol, timber rattle snake venom

Neuromyotonia symptoms

The signs and symptoms of neuromyotonia generally develop between ages 15 and 60, with most people showing symptoms before age 40. Although the symptoms can vary, affected people may experience:

- Progressive stiffness, cramping and weakness

- Muscle twitching with a rippling appearance (myokymia)

- Delayed muscle relaxation

- Diminished reflexes

- Muscle atrophy

- Ataxia (difficulty coordinating voluntary movements)

- Increased sweating (hyperhidrosis)

- Speech and breathing may also be affected if the muscles of the throat are involved. Smooth muscles and cardiac (heart) muscles typically are spared.

Acquired neuromyotonia or Issacs’ syndrome, is characterized by involuntary continuous muscle fiber activity (fasciculations) that cause progressive muscle stiffness and delayed relaxation in the affected muscles, even during sleep or when individuals are under general anesthesia. Muscle twitching with a rippling appearance (myokymia) may occur along with these symptoms. Affected individuals may, at times, be unable to coordinate voluntary muscle movement and find difficulty in walking (ataxia). Other symptoms may include staggering and reeling (titubation), stiffness, and lack of balance in response to being startled. There may be diminished spontaneous gross motor activity.

Neuromyotonia is characterized by progressive stiffness, cramping, and weakness. Muscle activity is constant, and patients describe the feeling of continuous writhing or rippling of muscles under the skin. These movements continue during sleep. Many people also develop weakened reflexes and muscle pain, but numbness is relatively uncommon. In some instances, muscle relaxation following voluntary muscle movement is delayed (grip myotonia) in the affected muscles. For example, affected individuals may be not be able to open their fists or eyes immediately after closing them tightly for a few seconds.

Affected individuals frequently have excessive sweating (hyperhidrosis), rapid heartbeats (tachycardia) and weight loss.

In most people with neuromyotonia, stiffness is most prominent in limb and trunk muscles, although symptoms can be limited to cranial muscles. Speech and breathing may be affected if pharyngeal or laryngeal muscles are involved. Onset is between ages 15 and 60, with most individuals experiencing symptoms before age 40. There are hereditary and acquired (occurring from unknown causes) forms of the disorder. The acquired neuromyotonia occasionally develops in association with peripheral neuropathies or after radiation treatment, but more often is caused by an autoimmune condition. Autoimmune-mediated neuromyotonia is typically caused by antibodies that bind to potassium channels on the motor nerve. Issacs’ syndrome is only one of several neurological conditions that can be caused by potassium channel antibodies.

In slightly fewer than 20% of the cases, a set of symptoms, including arrhythmias, excessive salivation, memory loss, confusion, hallucinations, constipation, personality change and/or sleep disorders, are found. In such cases the disorder may be referred to as Morvan syndrome.

Muscle twitching

Muscle twitching or ‘visible myokymia’ is observed as a continuous, undulating, wave-like rippling of muscles, likened to a bag of worms under the skin. This is usually the commonest symptom, seen in over 90% of patients. Twitching generally occurs in the limbs but can also be seen in the trunk muscles and the face, including the tongue. Rarely, the laryngeal muscles are involved, causing hoarseness and exertional dyspnea. Occasionally, there is no visible muscle twitching at all, but needle electromyography or EMG reveals continuous motor unit activity. However, muscle rippling can sometimes be felt on palpation, even when it is invisible to the naked eye.

Muscle cramps

Muscle cramps that can be painful at times are a prominent feature in over 70% of cases and are sometimes the first symptom that is noticed. They may be associated with spasms and are sometimes worsened by attempted voluntary muscle contraction or electrical nerve stimulation. Cold weather can also precipitate muscle cramps.

Muscle stiffness

This can occur in association with cramps, and can be severe enough to affect walking and manual dexterity. As a result, patients may adopt an abnormal posture and may be unable to stand on their heels due to stiffness in the lower limbs. Stiffness can also occur in the muscles of respiration resulting in breathlessness. Occasionally, stiffness can improve with repeated exercise. It is sometimes impossible to elicit the tendon reflexes due to the increased muscle tone.

Increased sweating

Hyperhidrosis, seen in about half the cases, is a systemic feature that is thought to arise as a result of an increase in the basal metabolic rate, perhaps due to continuous muscle activity. There is no evidence of continuous neural activity in the sudomotor nerves.

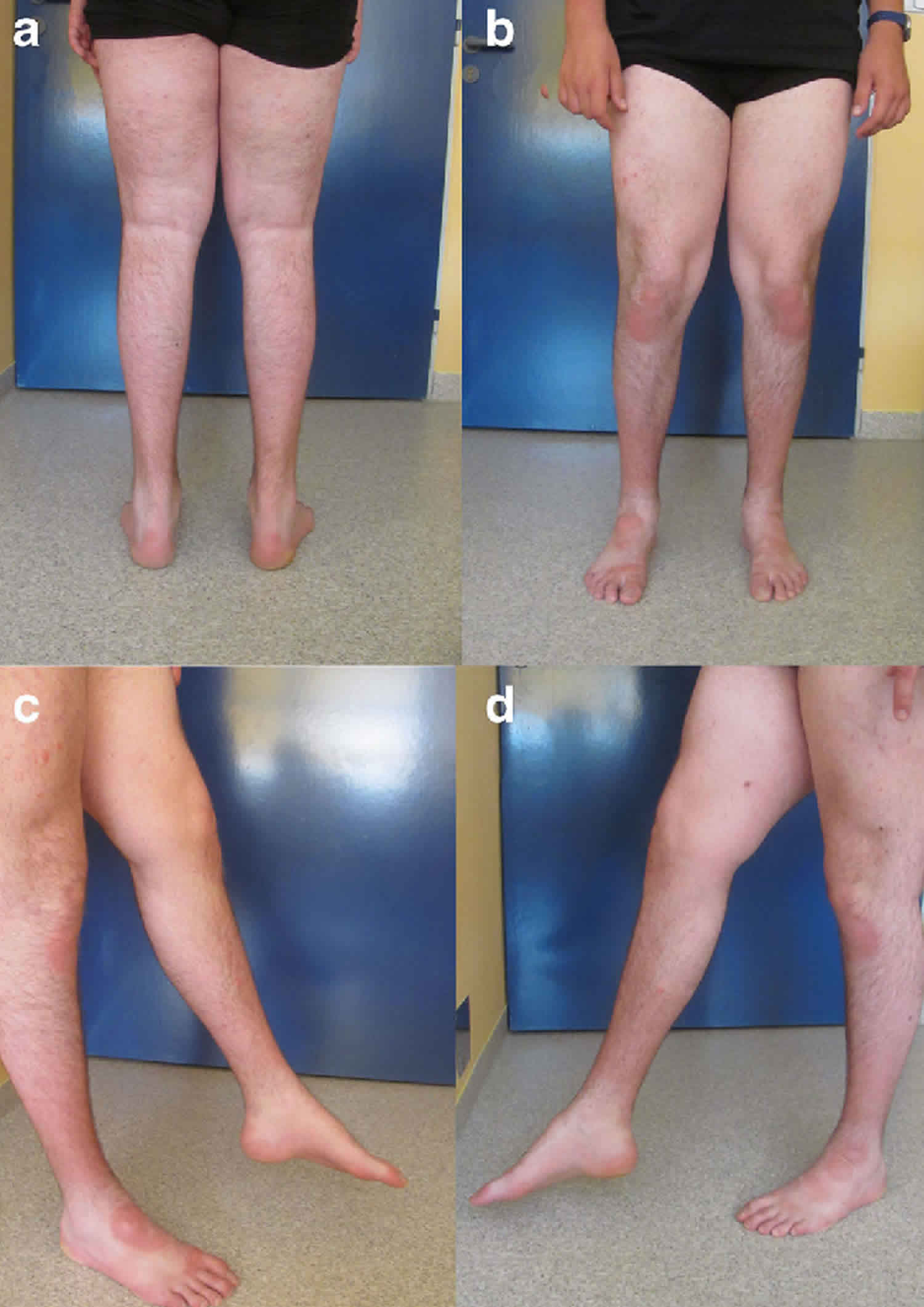

Muscle hypertrophy

Muscle hypertrophy is thought to arise as a result of continuous muscle activity. Most often the calves are hypertrophied but hypertrophy can also be seen in the forearm and hand muscles. The degree of hypertrophy seems to correlate with the severity of overactivity in individual muscle groups and is usually bilateral.

Pseudomyotonia

Pseudomyotonia describes a myotonic-like slow relaxation of muscles after voluntary contraction, for example abnormally slow release of hand grip. Unlike myotonic dystrophy, there is no evidence of percussion myotonia. Pseudomyotonia may be the first symptom and can occur on eye and jaw closure as well as on hand grip. Only about one third of patients exhibit this phenomenon.

Muscle weakness

Reduced muscle power is unusual, but has been reported with no additional cause for weakness, even when the weak muscles were hypertrophied. One cause for the muscular weakness may be fatigue in the presence of continuous muscle fiber activity.

Central nervous system symptoms

There are occasional reports of hallucinations, delusional episodes and insomnia, sometimes referred to as Morvan’s fibrillary chorea 7. Although oligoclonal bands have been found in the cerebrospinal fluid (CSF) of patients with autoimmune neuromyotonia, there is no correlation with disease severity or central symptoms. Detectable levels of antivoltage-gated potassium channel antibodies in the CSF have not been demonstrated.

Neuromyotonia diagnosis

The diagnosis of neuromyotonia or Isaacs’ syndrome is based on the presence of continuous muscle contractions (myokymia), especially in the face and hands, rhythmic tics or twitches (fasciculations), and muscle cramps. The diagnosis is confirmed by studies of the electrical signs of muscle activity (electromyography or EMG). Despite the fasciculations, needle tests of the muscle (EMG) do not show any other signs of denervation in the muscles. Myotonic discharges (distinctive bursts of muscle activity) can be seen on needle EMG. Sensory and motor nerve conduction tests are normal.

Additional testing can then be ordered to confirm the diagnosis, evaluate for associated conditions (i.e. malignancies and autoimmune disorders) and rule out other disorders that may cause similar features. This testing may included 3:

- Specialized laboratory studies on blood and/or urine. Voltage gated K channel (VGKC) antibodies may be present in the patient’s blood.

- Imaging studies such as a CT scan or MRI scan

- Electromyography (EMG) which checks the health of the muscles and the nerves that control them.

Neuromyotonia treatment

The treatment of neuromyotonia or Isaacs’ syndrome is based on the signs and symptoms present in each person. For example, antiepileptic medications such as phenytoin and carbamazepine, muscle relaxants may be prescribed to relieve stiffness, muscle spasms, and analgesics for muscle pain. In cases of severe symptoms, patients are required to undergo steroid pulse therapy, immunoglobulin therapy (IVIg therapy) and plasmapheresis. Plasma exchange (plasmapheresis) may provide short-term relief for people with some forms of acquired Isaacs’ syndrome. Plasma exchange is a method by which whole blood is removed from the body and processed so that the red and white blood cells are separated from the plasma (liquid portion of the blood). The blood cells are then returned to the patient without the plasma, which the body quickly replaces. If there is no response or poor response to plasma exchange, some studies suggest that intravenous infusions of immunoglobulins (IVIg therapy) may be beneficial 3. Intravenous immunoglobulin is made from pooled human serum or can be mad in the laboratory. This contains many different proteins that are thought to bind with disease causing antibodies and relieve the symptoms. Patients receive intravenous infusions of the IVIg at 4 weekly intervals.

As the abnormal discharge occurs at the neuromuscular junction, a proximal block might not suppress the discharge. In contrast, general anesthesia with neuromuscular blockade will abolish this discharge. Suppressing the abnormal muscle symptoms with only a local anesthetic agent would require considerably high concentrations. However, reports support the efficacy of muscle relaxants (depolarizing and non-depolarizing) and spinal and epidural anesthesia for suppressing spontaneous discharge 8.

Neuromyotonia prognosis

There is no cure for neuromyotonia. The long-term prognosis for individuals with Issacs’ syndrome is uncertain and largely depends on the underlying cause. In general, there is no cure for the condition although it is generally not fatal and patients are able to continue a normal life. Spontaneous remission has also been observed 2.

References- Hart IK, Waters C, Vincent A, Newland C, Beeson D, Pongs O, et al. Autoantibodies detected to expressed K+ channels are implicated in neuromyotonia. Ann Neurol. 1997;41(2):238–246. doi: 10.1002/ana.410410215

- Maddison P. Neuromyotonia. Practical Neurology 2002;2:225-229. https://pn.bmj.com/content/practneurol/2/4/225.full.pdf

- Ahmed A, Simmons Z. Isaacs syndrome: A review. Muscle Nerve. July 2015; 52(1):5-12.

- Sonoda Y, Arimura K, Kurono A, Suehara M, Kameyama M, Minato S, et al. Serum of Isaacs’ syndrome suppresses potassium channels in PC-12 cell lines. Muscle Nerve. 1996;19(11):1439–1446. doi: 10.1002/mus.880191102

- Isaacs H. A Syndrome of Continuous Muscle-Fibre Activity. J Neurol Neurosurg Psychiatry. 1961;24(4):319–325. doi: 10.1136/jnnp.24.4.319

- Vincent A, Palace J, Hilton-Jones D. Myasthenia gravis. Lancet. 2001;357(9274):2122–2128. doi: 10.1016/S0140-6736(00)05186-2

- Liguori R, Vincent A, Clover L et al. (2001) Morvan’s syndrome: peripheral and central nervous system and cardiac involvement with antibodies to voltage-gated potassium channels. Brain, 124, 2417–26.

- Hosokawa S, Shinoda H, Sakai T, Kato M, Kuroiwa Y. Electrophysiological study on limb myokymia in three women. J Neurol Neurosurg Psychiatry. 1987;50(7):877–881. doi: 10.1136/jnnp.50.7.877