Onychophagia

Onychophagia also known as onychotillomania, is the medical term for chronic fingernail biting 1. Onychophagia is a common stress-related or nervous habit in children and adults. It involves biting off the nail plate, and sometimes the soft tissues of the nail bed and the cuticle as well. Onychophagia includes the habit of picking or otherwise manipulating the nails. Chronic nail biting can also leave you vulnerable to infection as you pass harmful bacteria and viruses from your mouth to your fingers and from your nails to your face and mouth.

Nail biting typically begins in childhood, is most common during adolescence and can continue through adulthood, although the behavior often decreases or stops with age 2. Only few epidemiological studies provide the frequency or the prevalence of onychophagia and most data are limited to children and adolescents 3. It ranges from 20 to 33% during childhood and approximately 45% of teenagers are nail biters 4. Onychophagia is usually not observed before the age of 3 or 4 years. By the age of 18 years the frequency of nail biting decreases; however it may persist in some adults 5.

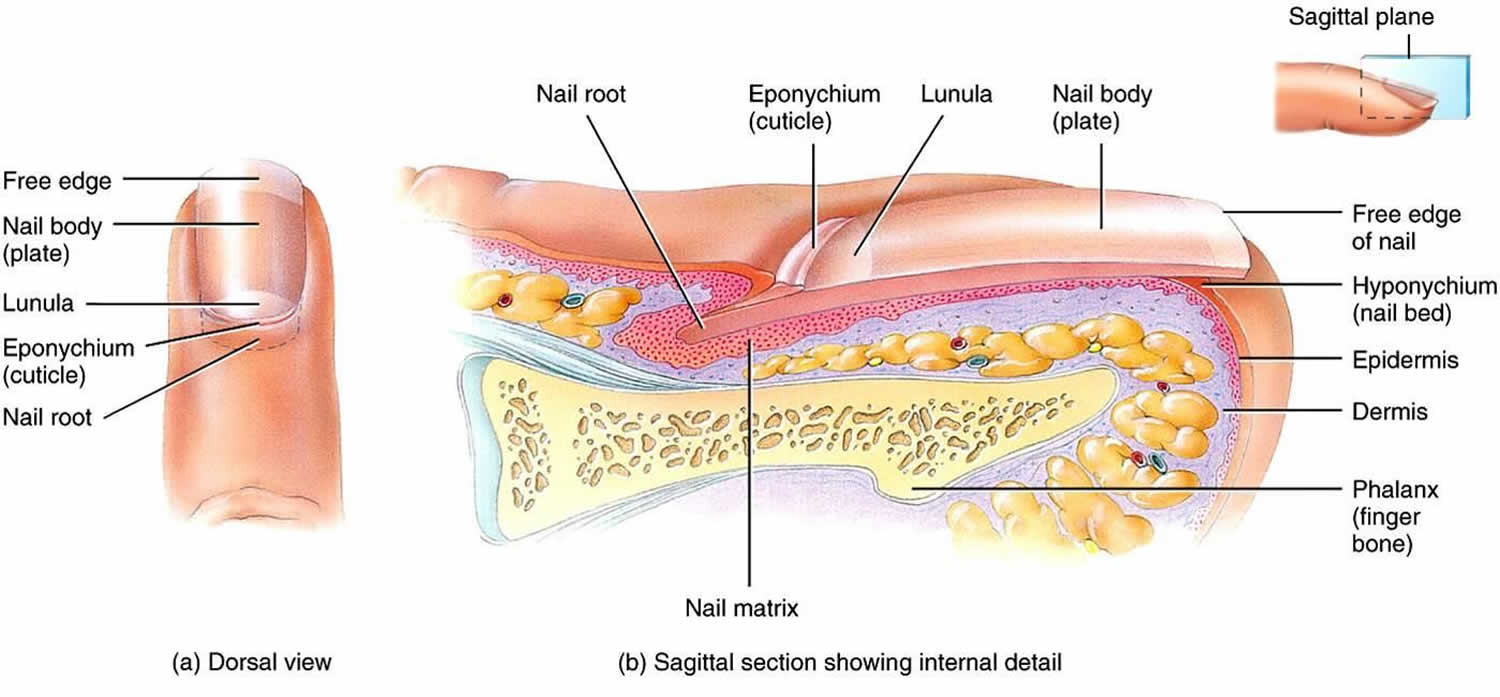

Onychophagia side effects can be more than cosmetic. Repeated nail biting can make the skin around your nails feel sore, and it can damage the tissue that makes nails grow, resulting in abnormal-looking nails. Nails are formed within the nail bed — just beneath where the U-shaped cuticles begin. As long as the nail bed remains intact, nail biting isn’t likely to interfere with fingernail growth. In fact, some research suggests that nail biting might even promote faster nail growth.

Doctors classify chronic nail biting as a type of obsessive-compulsive disorder (OCD) since the person has difficulty stopping. People often want to stop and make multiple attempts to quit without success. People with onychophagia cannot stop the behavior on their own, so it’s not effective to tell a loved one to stop.

Onychophagia can cause distress, emotional tension or social embarrassment. It is associated with other habit disorders, including trichotillomania (hair pulling) and dermatillomania (compulsive skin picking).

It is also important to note that nail biting can also cause physical problems, including:

- Stomach infections resulting from the swallowing the bitten nails

- Fungal infections of the nail plate (onychomycosis) and surrounding skin (paronychia)

- Harm your teeth

- Teeth root resorption

- Alveolar destruction

- Intestinal parasitic infections

- Temporomandibular joint pain and dysfunction

- Damage the skin around the nail, increasing the risk of infection

- Increase the risk of colds and other infections by spreading germs from your fingers to your mouth.

If you’re concerned about nail biting, consult your doctor or a mental health provider. The treatment for onychophagia depends on the severity of the nail-biting habit:

- No treatment is necessary for mild onychophagia as a child can often outgrow the habit.

- Avoiding factors that trigger nail biting, such as overstimulation.

- Occupying your hands or mouth with alternate activities, such as playing a musical instrument or chewing gum.

- Taking healthy steps, such as getting active, to manage stress and anxiety.

- Dermatologists recommend keeping the nails short and neatly trimmed, manicured, or covered to minimize the temptation to nail-bite.

- The application of bitter-tasting compounds to the nails to discourage nail biting is controversial and not very effective.

- In some cases, treatment with behavior therapy might be needed.

- Any underlying mental health problem or psychiatric disorder should also be managed.

Figure 1. Nail anatomy

When is nail biting a problem that needs medical attention?

If nail biting causes physical harm and psychological distress, then professional treatment is necessary. Usually, the person knows the behavior is problematic, but they can’t control it on their own. It is important to seek help if the behavior is affecting mental and physical health:

- Damage to the nail, cuticle or surrounding skin.

- Bacterial infection.

- Dental concerns.

- Psychological damage (shame, low self-esteem, depression).

- Relationship problems.

What’s behind chewed-to-the-nub nail biting?

For most people, nail biting is an occasional thing. When people can’t stop the behavior on their own, doctors consider it a type of body-focused repetitive behavior (BFRB). Doctors refer to chronic nail biting as onychophagia and they don’t fully understand the cause (though there may be a genetic component). Scientists do know that people with these conditions often have onychophagia as well:

- Attention deficit hyperactivity disorder (ADHD): Hyperactivity and impulsiveness, plus difficulty paying attention.

- Oppositional defiant disorder: Defiance and disobedience toward people of authority.

- Separation anxiety disorder: Excessive anxiety when separated from particular people or pets.

- Tourette syndrome: Involuntary movements and sounds.

- Other body-focused repetitive behaviors: Chronic skin picking, hair pulling, cheek biting and grinding teeth.

Are there specific triggers for onychophagia?

The behavior is typically automatic — people don’t realize they’re doing it. Chronic nail biting often has a self-soothing quality (it provides a sense of calm), so people may use it as a coping mechanism. Sometimes, a hangnail or nail imperfection could spur someone to excessively groom the nail. Their goal is to improve the look of the nail, but unfortunately, the nail often ends up looking worse. They don’t intend to self-harm — it’s a grooming behavior run amok. Other triggers could be boredom, needing to concentrate or a stressful situation.

Onychophagia causes

To date, the exact cause of onychophagia remains as yet unclear. Although it has been observed that nail biters have more anxiety than those who do not have the habit, no relevant relationship was found between nail biting and anxiety 6. Others support that onychophagia is a learned behavior from family members, which most likely seems consistent with a process of imitation 7. Some researchers believe that nail biting is a result of a delay or dysfunction in the oral stage of psychological development.

While it does not cause them, onychophagia is associated with a variety of psychiatric disorders, including:

- Obsessive–compulsive disorder (OCD)

- Attentional deficit hyperactivity disorder (ADHD)

- Oppositional defiant disorder (ODD)

- Separation anxiety disorder

- Tourette syndrome

- Other body-focused repetitive behaviors: Chronic skin picking, hair pulling, cheek biting and grinding teeth.

Onychophagia symptoms

Onychophagia is the medical term for chronic nail biting. Nail biting is associated with a variety of medical and dental problems. Besides the persistently embarrassing and socially undesirable cosmetic problem, onychophagia is responsible for recurrent chronic paronychia, subungual infection, onychomycosis, or severe damage to the nail bed causing onycholysis 3.

On the other hand, just like any other oral parafunction, onychophagia may cause temporomandibular dysfunction 8. Moreover, biting pressure can be transferred down from the crown to the root leading to small fractures at the edges of incisors, apical root resorption, alveolar destruction, or gingivitis 2.

If left untreated, severe onychophagia can lead to dysmorphic dental problems, including 2:

- Malocclusion (imperfect positioning) of the front teeth

- Crowding, attrition and rotation of the teeth noted on X-rays

- Attrition of the incisional edge of the mandibular incisors (lower front teeth)

- Protrusion of the maxillary incisors (upper front teeth).

These problems can affect the individual’s physical appearance, but this can be avoided if the nail-biting habit is broken early.

In addition to the visible damage to fingernails, onychophagia may co-occur with other body-focused repetitive behaviors, such as hair pulling (trichotillomania) or skin picking (dermatillomania). Symptoms are both psychological and physical. People who chronically bite their nails may experience:

- distressful feelings of unease or tension prior to biting

- feelings of relief or even pleasure after biting

- feelings of shame, embarrassment, and guilt, often related to the appearance of physical damage to skin and nails caused by biting

- tissue damage to fingers, nails, and cuticles

- mouth injuries, dental problems, abscesses, and infections

- in some cases, onychophagia may lead to complicated family and social relationships

Onychophagia diagnosis

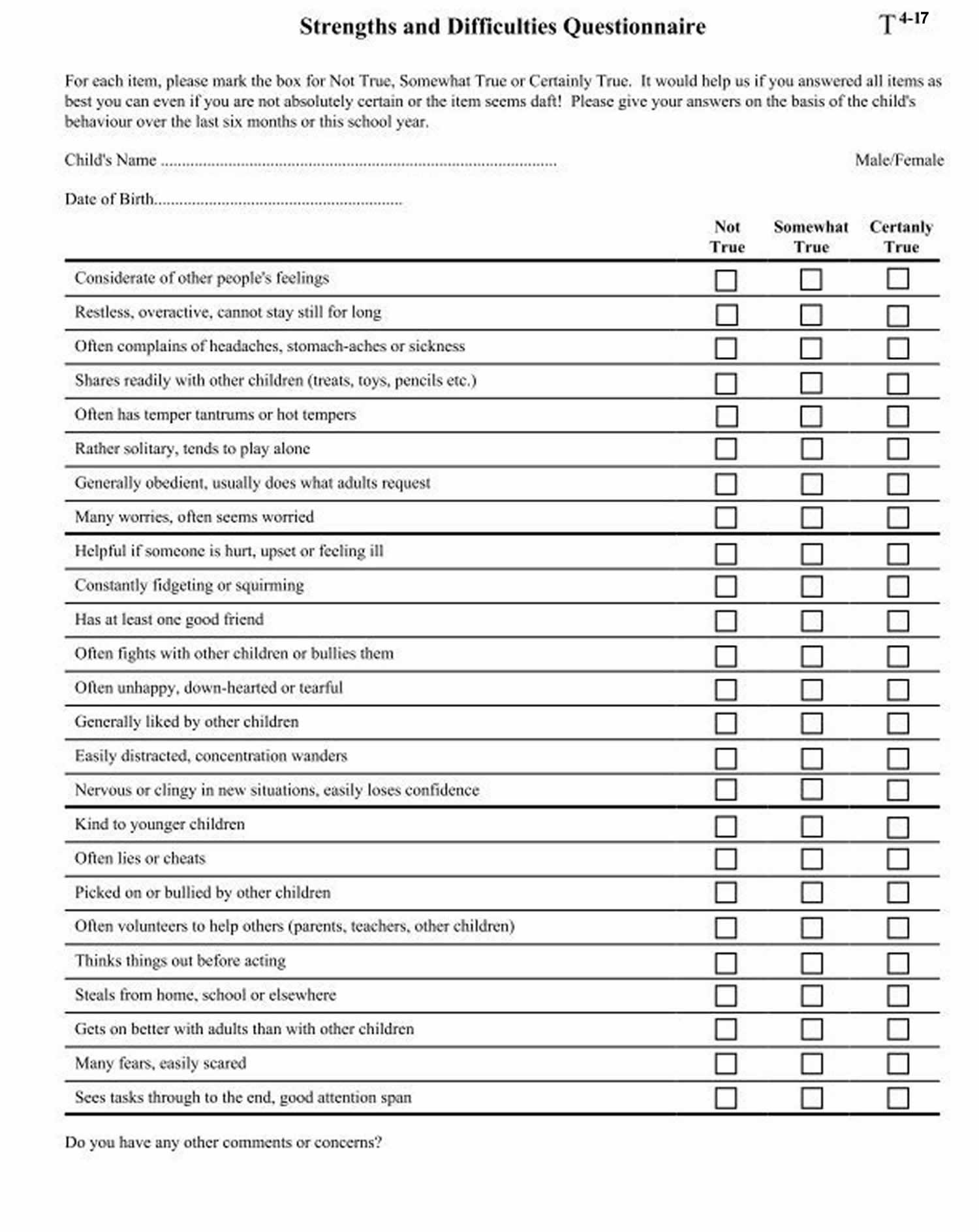

While there is no assessment tool specific to onychophagia itself, some research has centered on the Strengths and Difficulties Questionnaire (SDQ). The Strengths and Difficulties Questionnaire (SDQ) is a brief behavioral screening questionnaire. It exists in several versions to meet the needs of researchers, clinicians and educationalists. Dr Robert Goodman, based in the United Kingdom, initially developed the tool for use in the mental health field but over the years it has been enhanced to use across a number of settings. The Strengths and Difficulties Questionnaire is a mental health tool is able to assess a variety of emotional and behavior problems, including inattention and hyperactive behavior, emotional symptoms, conduct problems, and prosocial behavior. When dealing with onychophagia, it can be useful to consider the issues covered in this questionnaire as a way to look for relationships/associations that may influence the individual’s nail-biting habit.

The Strengths and Difficulties Questionnaire consists of three questionnaires that are filled out: one by the teacher, one by the student (dependant on age) and one by the parents. Each questionnaire consists of 25 questions assessing the following areas:

- 5 on emotional symptoms

- 5 on conduct problems

- 5 on hyperactivity

- 5 on peer relationship problems

- 5 on pro social behavior

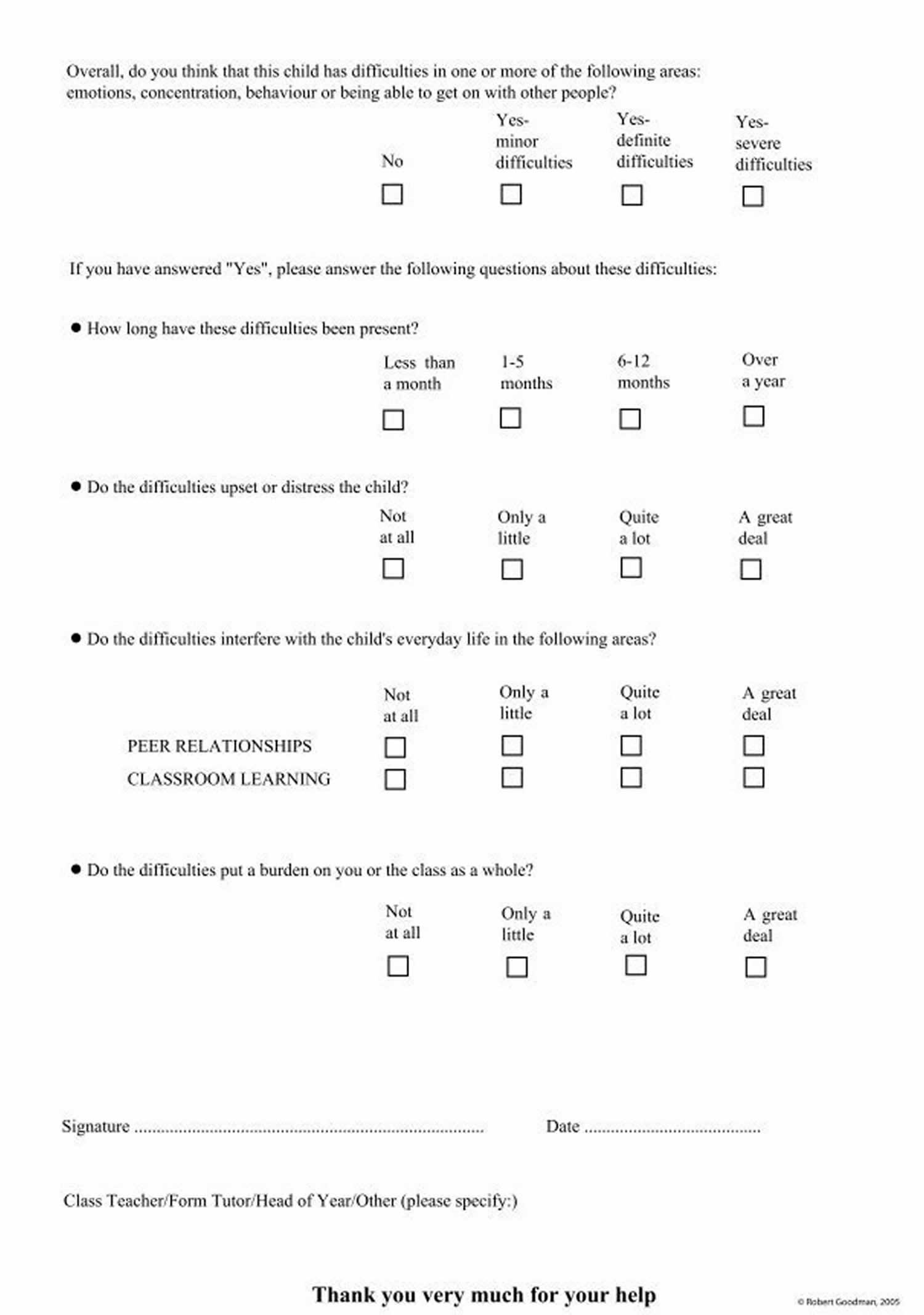

There is a short impact supplement, consisting of 5 questions on the reverse side of the questionnaire.Additionally, there is a follow-up questionnaire to measure the change in the child/young person. This is to be used when you are doing a post Strengths and Difficulties Questionnaire (SDQ) assessment.

The following is an example of the Strengths and Difficulties Questionnaire. Note the 25 questions on the front side and the T 4-17 code in the top left hand corner, which identifies this as the questionnaire for the parent to fill out, answering the questions about their 4-17 year old child/young person.

Scoring

Once the questionnaires have been filled out the Strengths and Difficulties Questionnaire assessment is then scored to show the level of difficulty on a numerical scale.

- Each psychological attribute is scored on a 0–10 scale.

- A score of 0 is the best outcome concerning the emotional, conduct, hyperactivity, and peer relationship fields (note that these four attributes add up to a total difficulties/overall stress score scored on a 0-40 scale).

- This scoring reverses for pro-social/score for kind and helpful behavior, where a score of 10 shows the least amount of difficulty.

Figure 1. Strengths and Difficulties Questionnaire

Onychophagia treatment

To help you stop biting your nails, doctors recommend following these tips:

- Keep your nails trimmed short. Having less nail provides less to bite and is less tempting.

- Apply bitter-tasting nail polish to your nails. Available over-the-counter, this safe, but awful-tasting formula discourages many people from biting their nails. The application of bitter-tasting compounds to the nails to discourage nail biting is controversial and not very effective.

- Get regular manicures. Spending money to keep your nails looking attractive may make you less likely to bite them. Alternatively, you can also cover your nails with tape or stickers or wear gloves to prevent biting.

- Replace the nail-biting habit with a good habit. When you feel like biting your nails, try playing with a stress ball or silly putty instead. This will help keep your hands busy and away from your mouth.

- Identify your triggers. These could be physical triggers, such as the presence of hangnails, or other triggers, such as boredom, stress, or anxiety. By figuring out what causes you to bite your nails, you can figure out how to avoid these situations and develop a plan to stop. Just knowing when you’re inclined to bite may help solve the problem.

- Try to gradually stop biting your nails. Some doctors recommend taking a gradual approach to break the habit. Try to stop biting one set of nails, such as your thumb nails, first. When that’s successful, eliminate your pinky nails, pointer nails, or even an entire hand. The goal is to get to the point where you no longer bite any of your nails.

- Treatment of any psychiatric disorders: People with chronic nail biting may need medications or behavioral therapy to address a related condition.

For some people, nail biting may be a sign of a more serious psychological or emotional problem. If you’ve repeatedly tried to quit and the problem persists, consult a doctor. Behavioral therapy can help release the shame and negative emotions that often accompany nail biting. It can also help increase awareness of the triggers and urges you feel. In some cases, habit-reversal training or hypnotherapy are effective.

If you bite your nails and develop a skin or nail infection, consult a board-certified dermatologist.

References- O. Marouane, M. Ghorbel, M. Nahdi, A. Necibi, N. Douki, “New Approach to Managing Onychophagia”, Case Reports in Dentistry, vol. 2016, Article ID 5475462, 5 pages, 2016. https://doi.org/10.1155/2016/5475462

- O. M. Tanaka, R. W. F. Vitral, G. Y. Tanaka, A. P. Guerrero, and E. S. Camargo, “Nailbiting, or onychophagia: a special habit,” American Journal of Orthodontics and Dentofacial Orthopedics, vol. 134, no. 2, pp. 305–308, 2008.

- P. Pacan, M. Grzesiak, A. Reich, and J. C. Szepietowski, “Onychophagia as a spectrum of obsessive-compulsive disorder,” Acta Dermato-Venereologica, vol. 89, no. 3, pp. 278–280, 2009.

- A. K. C. Leung and W. L. M. Robson, “Nailbiting,” Clinical Pediatrics, vol. 29, no. 12, pp. 690–692, 1990.

- L. Gregory, “Stereotypic movement disorder and disorder of infancy, childhood, or adolescence NOS,” in Comprehensive Textbook of Psychiatry, pp. 2360–2362, Williams & Wilkins, Baltimore, Md, USA, 6th edition, 1995.

- P. A. Deardoff, A. J. Finch Jr., and L. R. Royall, “Manifest anxiety and nail-biting,” Journal of Clinical Psychology, vol. 30, no. 3, p. 378, 1974.

- M. Massler and A. J. Malone, “Nail biting-a review,” American Journal of Orthodontics, vol. 36, no. 5, pp. 351–367, 1950.

- E. Winocur, D. Littner, I. Adams, and A. Gavish, “Oral habits and their association with signs and symptoms of temporomandibular disorders in adolescents: a gender comparison,” Oral Surgery, Oral Medicine, Oral Pathology, Oral Radiology, and Endodontology, vol. 102, no. 4, pp. 482–487, 2006.