Overlap syndrome

An overlap syndrome is an autoimmune disease in which the patient presents with symptoms of two or more diseases 1. As much as 25% of all patients with connective tissue disease show signs of an overlap syndrome. Examples of overlap syndromes are scleroderma that can occur with other autoimmune diseases, including systemic lupus erythematosus (SLE) and polymyositis or mixed connective tissue disease and scleromyositis, but the exact diagnosis depends from which diseases the patient shows symptoms. In overlap syndromes features of systemic lupus erythematosus (SLE), systemic sclerosis, polymyositis, dermatomyositis, rheumatoid arthritis (RA) and Sjögren’s syndrome are found most commonly 1.

In overlap syndrome, features of the following diseases are found (most common listed) 1:

- Systemic lupus erythematosus (SLE)

- Systemic sclerosis

- Polymyositis

- Dermatomyositis

- Rheumatoid arthritis (RA)

- Sjögren’s syndrome

- Eosinophilic granulomatosis with polyangiitis

- Autoimmune thyroiditis

- Antiphospholipid antibody syndrome

The treatment of overlapping connective tissue disorders is mainly based on the use of corticosteroids and immunosuppressants. Biologic drugs, i.e. anti-TNFα or anti-CD20 monoclonal antibodies, have been recently introduced as alternative treatments in refractory cases. There are some concerns with the use of anti-TNF agents in patients with systemic autoimmune diseases due to the risk of triggering disease exacerbations 2.

The term polyangiitis overlap syndrome refers to a systemic vasculitis that shares features with two or more distinct vasculitis syndromes. The most common type of polyangiitis overlap syndrome is microscopic polyangiitis, which shares features with eosinophilic granulomatosis with polyangiitis, granulomatosis with polyangiitis and panarteritis nodosa. Sometimes polyangiitis overlap syndrome is used as a synonym for microscopic polyangiitis 3.

In gastroenterology, the term overlap syndrome may be used to describe autoimmune liver diseases that combine characteristic features of autoimmune hepatitis, primary biliary cirrhosis and primary sclerosing cholangitis 4.

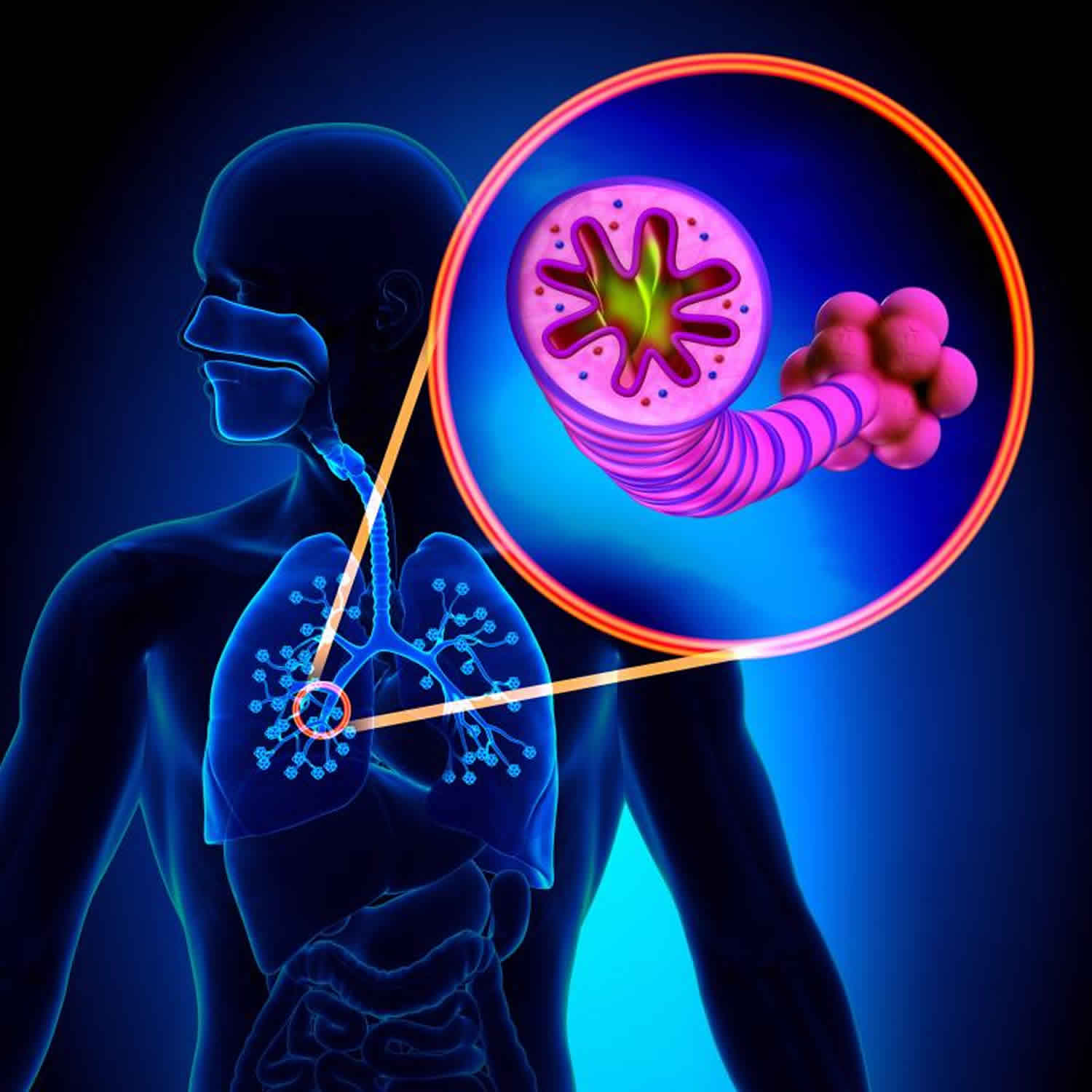

Asthma and COPD overlap syndrome

Asthma–COPD overlap syndrome (ACOS) has been applied to the condition in which a person has clinical features of both asthma and COPD 5. Approximately 1 in 12 people worldwide are affected by asthma or chronic obstructive pulmonary disease (COPD) 6; once regarded as two distinct disease entities, these two conditions are now recognized as heterogeneous and often overlapping conditions 7. However, on the basis of information presented in this review 5, the authors believe that it is premature to recommend the designation of asthma COPD overlap syndrome (ACOS) as a disease entity in primary and specialist care. More research is needed to better characterize patients and to obtain a standardized definition of asthma COPD overlap syndrome (ACOS) that is based on markers that best predict treatment response in individual patients 5.

Asthma is an inflammatory disease that affects the large and small airways. It typically develops in childhood and is often accompanied by allergies, although asthma develops in adulthood in a subgroup of patients 8. Patients with asthma have bouts of breathlessness, chest tightness, coughing, and wheezing that are due to generalized airway obstruction, which is manifested as decreased flow rates over the entire vital capacity and a diminished forced expiratory volume in 1 second (FEV1) that usually reverts completely after the attack. This airway obstruction results predominantly from smooth-muscle spasm, although airway mucus and inflammatory infiltrates also contribute. Bronchial hyperresponsiveness, an enhanced bronchoconstrictor response to inhaled stimuli, is a common and core feature of asthma but is not sufficiently specific to establish a firm diagnosis 8.

COPD is also an inflammatory airway disease, one that affects the small airways in particular 6. In chronic bronchitis, there are inflammatory infiltrates in the airways, especially the mucus secretory apparatus, whereas in emphysema, there are clusters of inflammatory cells near areas of alveolar-tissue breakdown. Chronic bronchitis and emphysema often coexist, although there are patients in whom one phenotype predominates. COPD usually becomes symptomatic with breathlessness in persons older than 40 to 45 years of age and is frequently associated with chronic cough, phlegm, wheezing, or a combination of these. Airway obstruction results from smooth-muscle contraction, airway mucus, tissue breakdown, or a combination of these, with loss of lung elastic recoil leading to airway closure. This form of airway obstruction is progressive in many patients. COPD is caused primarily by smoking, although passive smoking, air pollution, and occupational exposures can cause the condition as well 6.

Airway inflammation in asthma differs from that in COPD. Asthma is characterized predominantly by eosinophilic inflammation and inflammation involving type 2 helper T (Th2) lymphocytes, whereas COPD is characterized predominantly by neutrophilic inflammation and inflammation involving CD8 lymphocytes 6. The clinical extremes of asthma and COPD are easily recognized in differences in symptoms and in the age of the patients. Particularly in older patients, the presentation of asthma and COPD may converge clinically and mimic each other. Irreversible airway obstruction develops over time in some patients with asthma owing to airway remodeling, with the result that these patients with asthma resemble those with COPD. In contrast, reversible airway obstruction can occur in patients with COPD, with the result that these patients with COPD resemble those with asthma. Recently, the Global Initiative for Asthma 8 and the Global Initiative for Chronic Obstructive Lung Disease 6 issued a joint document that describes asthma COPD overlap syndrome as a clinical entity and proposes that clinicians should assemble the features for asthma and for COPD that best describe the patient and compare the number of features in favor of each diagnosis. Even though overlaps between asthma and COPD are a clinical reality, the Global Initiative for Asthma 8 and Global Initiative for Chronic Obstructive Lung Disease documents have not given a specific definition of asthma COPD overlap syndrome and have stated that more evidence on “clinical phenotypes and underlying mechanisms” is needed 6. In practice, if three or more features of either asthma or COPD are present, that diagnosis is suggested; if there are similar numbers of features of asthma and COPD, the diagnosis of asthma COPD overlap syndrome should be considered. The relevant variables are age at onset, pattern and time course of symptoms, personal history or family history, variable or persistent airflow limitation, lung function between symptoms, and severe hyperinflation.

According to a case definition of asthma COPD overlap syndrome that has been widely promulgated, the syndrome is estimated to be present in 15 to 45% of the population with obstructive airway disease, and the prevalence increases with age 9. However, despite this presumed high prevalence, no double-blind, prospective studies have been conducted to provide information on how to treat these types of patients. Indeed, studies of COPD have excluded nonsmokers and patients with some bronchodilator reversibility, whereas studies of asthma have excluded smokers and patients without substantial bronchodilator reversibility. Thus, the most effective treatment of patients with asthma COPD overlap syndrome remains unknown.

Asthma and COPD treatment

Global Initiative for Asthma 8 and the Global Initiative for Chronic Obstructive Lung Disease 6 provide well-defined treatment and management plans for clear cases of asthma and COPD. For example, for the patient with “easy” asthma, a stepwise approach is recommended on the basis of disease severity, with the clinical aim of disease control and future risk reduction. The main pillars of treatment are inhaled glucocorticoids in combination with bronchodilator drugs, in particular short-acting beta-agonists and long-acting beta-agonists (LABAs). Leukotriene-receptor antagonists are an alternative choice in milder disease.1 For severe allergic asthma with appropriate IgE levels, anti-IgE treatment is an approved option; long-acting muscarinic antagonists (LAMAs) have been shown to work in controlled trials and are now included in the treatment of severe asthma but are not approved by the Food and Drug Administration (FDA) for this use 8.

For the patient with “easy” COPD, a stepwise treatment approach is also recommended, with a focus on reduction of symptoms and exacerbations and acknowledgment of the role of coexisting conditions. The main emphasis is on smoking cessation and the use of long-acting beta-agonists (LABAs) and long-acting muscarinic antagonists (LAMAs). The role of inhaled glucocorticoids has been debated for years and is limited to patients with more severe disease and those with frequent exacerbations 6.

Given the lack of randomized intervention studies of asthma COPD overlap syndrome, it is difficult to provide firm treatment guidance for patients with the asthma COPD overlap syndrome. Experts believe that treatment with inhaled glucocorticoids should be continued in patients with long-standing asthma even if a component of irreversible airway obstruction develops; leukotriene modifiers may be of value in those with atopy. Combination therapy with a long-acting muscarinic antagonist and a long-acting beta-agonist is a well-established treatment and is a reasonable approach for patients with more severe asthma or COPD or with overlapping conditions. However, given the ongoing debate on the safety of long-acting beta-agonists in people with asthma, any suspicion of an asthmatic component in a given person should definitely prompt the use of inhaled glucocorticoids.

Traditionally, COPD is characterized by a relevant smoking history, persistent and progressive airway obstruction, lack of reversibility of airway obstruction, and neutrophil infiltration in the airways. As noted above, we now appreciate that reversibility, eosinophilia, and bronchial hyperresponsiveness may be present in patients with COPD. Experts think that patients who have any of these asthmalike features might benefit from inhaled glucocorticoids. This approach should be evaluated in large clinical-effectiveness studies with extensive phenotyping at baseline. Notably, such studies need to expand on alternative outcome measures, because patients with COPD and concomitant signs of asthma may not have easily measured changes in FEV1 in response to treatment and over a short period of time 10.

References- Overlap syndromes and mixed connective tissue disease. Curr Opin Rheumatol. 1991 Dec;3(6):995-1000. DOI:10.1097/00002281-199112000-00016

- Overlap connective tissue disease syndromes. Autoimmun Rev. 2013 Jan;12(3):363-73. doi: 10.1016/j.autrev.2012.06.004. Epub 2012 Jun 26. https://doi.org/10.1016/j.autrev.2012.06.004

- Polyangiitis overlap syndrome. Classification and prospective clinical experience. Am J Med. 1986 Jul;81(1):79-85. https://doi.org/10.1016/0002-9343(86)90186-5

- Overlap syndromes of autoimmune hepatitis: diagnosis and treatment. Rev Gastroenterol Mex. 2015 Apr-Jun;80(2):150-9. doi: 10.1016/j.rgmx.2015.04.001. Epub 2015 Jun 16. https://doi.org/10.1016/j.rgmx.2015.04.001

- The Asthma–COPD Overlap Syndrome. N Engl J Med 2015; 373:1241-1249 DOI: 10.1056/NEJMra1411863 https://www.nejm.org/doi/full/10.1056/NEJMra1411863

- Global Initiative for Chronic Obstructive Lung Disease. Global strategy for the diagnosis, management, and prevention of chronic obstructive pulmonary disease. https://goldcopd.org

- Barker BL, Brightling CE. Phenotyping the heterogeneity of chronic obstructive pulmonary disease. Clin Sci (Lond) 2013;124:371-387

- Global Initiative for Asthma. Global strategy for asthma management and prevention. https://ginasthma.org

- de Marco R, Pesce G, Marcon A, et al. The coexistence of asthma and chronic obstructive pulmonary disease (COPD): prevalence and risk factors in young, middle-aged and elderly people from the general population. PLoS One 2013;8:e62985-e62985

- Christenson SA, Steiling K, van den Berge M, et al. Asthma-COPD overlap: clinical relevance of genomic signatures of type 2 inflammation in COPD. Am J Respir Crit Care Med 2015;191:758-766