Photopsia

Photopsias are flashes of light that are usually brief and intermittent 1. While a photopsia may be a disturbing event on its own, especially if the condition comes and goes without regularity, this is not a medical problem by itself. Photopsias are typically symptoms of another condition. Photopsias (flashes of light) are a common presenting symptoms in the ophthalmology clinic. Although the majority of photopsias are retinal in origin 1, characterizing the appearance, onset, and associated features is critical in determining the cause of photopsia.

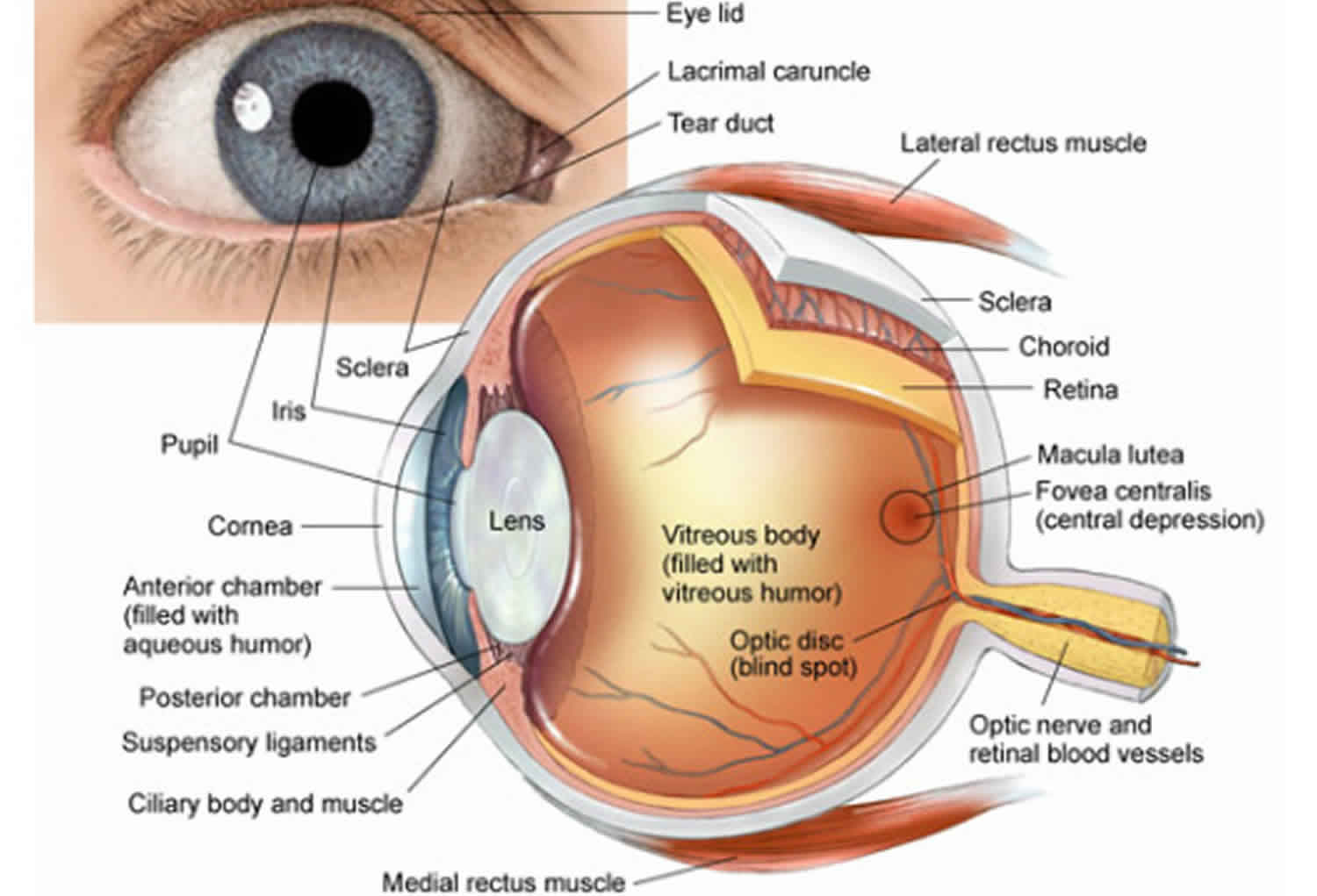

Many, many conditions can cause photopsias and these can be benign or problematic – various sources of photopsia are vitreoretinal traction, ocular migraines, age-related macular degeneration (AMD), diabetes, cerebral blood flow, visual hallucinations, cancer associated retinopathy, entoptic phenomenon, phosphenes, and lens associated dysphotopsias. They can be caused by problems with the vitreous, retina and nerve of the eye. They can also be neurological in origin and not related to any eye issue. Therefore, the causes and treatments can only be determined by a comprehensive eye exam by an ophthalmologist.

Photopsia causes

Some of the most common conditions leading to photopsias include:

- Age-related macular degeneration. Often shortened to AMD, this is a common condition in the eyes of people who are 50 or older. The macular is the part of the eye that helps you see clearly in front of you. This is called central vision. Age-related macular degeneration (AMD) is the slow degeneration of the macula, leading to a loss of clear central vision. Some of the early warning signs of AMD include developing photopsias. Exudative (i.e., neovascular or wet) AMD, a common cause of photopsias and the second most common cause in one reported case series 1. Approximately 50% of individuals with exudative AMD report experiencing repeated centrally located flashes that last for several seconds to a few minutes. These flashes are typically described as flickers, pulsations, sparkling lights, snake-like lights, spinning lights, pinwheels, or circles. These lights are most commonly white in color, but people have reported seeing blue, silver, gold, or multiple colored lights 1. The likelihood of reported photopsias increases as the neovascular membranes increases in area. Unlike the photopsias of posterior vitreous detachment, which are stimulated from the inner retina-vitreous interface, the photopsias from exudative AMD occur from accumulating fluid stimulating the outer retina layers 1. Differentiating between the two may sometimes be difficult prior to exam; however, central flashes are far more common with AMD and peripheral flashes are more common with posterior vitreous detachment 1.

- Ocular migraine. Most people think of migraines as recurring headaches, but there are other symptoms alongside migraines that may not be just pain, physical sensitivity, soreness, or sensitivity to light or sound. Visual changes called auras (a type of photopsia) are associated with migraines affecting the eyes or ocular migraine. Visual snow or static can also be symptoms of ocular migraines. Although the visual phenomenon typically occurs bilaterally, the photopsias may appear larger in one eye than the other 1. Visual symptoms can occur with every migraine headache an individual has or may only happen once 1. Migraine and auras are not fully understood, and there is much debate around their underlying mechanisms. A leading theory is that migraines are caused by disturbances in cerebral blood flow and a wave of depressed neuronal activity moves slowly across the brain; this process usually starts in the occipital lobe and spreads anteriorly. A migraine aura likely is a result of the initial wave of high neuronal activity related to the previously described spreading depression followed by an inhibition of activity 2. Auras can manifest as small bright lights, blind spots, static/foggy vision, and/or complex visual disturbances. Typically, auras begin prior to the headache as a central crescent-shaped scintillating scotoma that expands outwards and is surrounded by flashes or zigzags of light 3. In a retinal migraine, a patient experiences decrease in vision or complete blindness in one eye without a scintillating scotoma; this is due to vasospasm of the retinal circulation or ophthalmic artery. Vision in a retinal migraine promptly returns to normal. A very uncommon form of migraine is an ophthalmoplegic migraine, which can cause a temporary paralysis of one of the three cranial nerves involved in ocular motion (CN III, CN IV, and CN VI) but is not associated with photopsias 4.

- Optic neuritis. This is inflammation that damages the optic nerve, leading to changes in how visual images are processed in the brain. The most common cause of optic nerve degeneration is multiple sclerosis. Flickering lights or flashes in the field of vision, along with pain, loss of color perception, and eventual vision loss are also part of damage to the optic nerve during optic neuritis.

- Posterior Vitreous Detachment, Retinal Tears, and/or Retinal Detachment

- Peripheral vitreous detachment. The vitreous humor in the eyes is the gel that spans the entire inside of the eye, keeping the shape and aiding support of structures within the organ. If the vitreous humor detaches from part of the eye, this can cause serious structural problems. When the gel detaches from the retina, at the back of the eye, it may lead to slow loss of peripheral vision. This is most likely to occur due to age — older adults are more likely to experience peripheral vitreous detachment — but it can also occur spontaneously, due to an accident, or because of an illness. When it occurs too fast, this may cause flashes of light and floaters to appear in the visual field; however, these photopsias typically go away in a few months. Photopsias occur as the vitreous pulls on the retina. The tension from the vitreous on the retina causes retinal cells to fire and leads to the perception of flashes of light. These flashes typically last less than one second and are described as a lightning streak or a camera flash in the periphery. The shape of the lightning streak is usually curvilinear due to the edge of the vitreoretinal traction. Photopsias can occur unilaterally or bilaterally, but bilateral flashes typically occur at different times in each eye. A posterior vitreous detachment is a common cause of floaters and photopsias in the general population, accounting for approximately 40% of patients presenting with these symptoms 1. Floaters are typically due to cells or debris floating in the vitreous that cast shadows onto the retina. Patients also often describe seeing a large opaque floater as the vitreous separates from around the optic nerve head 5. On clinical examination, this vitreous separation from the circular optic nerve can be seen as a Weiss ring.

- Retinal tears. Retinal tears can also cause floaters and flashes of light in the periphery 1. Retinal tears due to traction from trauma or posterior vitreous detachment are typically horseshoe shaped, and, if large enough, the vitreous enters the subretinal space causing a rhegmatogenous retinal detachment 6. Surgical intervention is required for rhegmatogenous retinal detachments, which are associated with persistent and progressive decrease in vision that patients typically described as a curtain or veil in their visual field. Differentiating between an acute posterior vitreous detachment and retinal tears can be difficult based on history alone. Hollands, et al. found that 14% of patients presenting with floaters and/or flashes and a diagnosis of posterior vitreous detachment also have a retinal tear; however, if there is no subjective decline in visual acuity, this risk decreases to 8.9% 7. Conversely, if the patient reports a subjective decrease in visual acuity or a vitreous hemorrhage is seen, then the risk of a tear increases to 45% and 62%, respectively. If vitreous pigment (i.e., Shafer’s sign) is noted, then the risk of a retinal tear is as high as 88% 7. In patients diagnosed with a posterior vitreous detachment without a retinal tear, 3.4% had a retinal tear within six weeks of their initial presentation 7. Thus, all patients should have a repeat dilated fundus examination within 4-6 weeks after initial presentation.

- Retinal detachment. The back of the eye contains the retina, which has a series of photosensitive receptor cells that collect information from light and transmit this data to the brain to be converted into images. If the retina detaches due to illness or injury, it can cause changes to the vision, including vision loss. Retinal detachment is a serious medical problem that needs immediate treatment. Suddenly experiencing floaters, light flashes, or other photopsias when you did not before could be a sign of this problem. It may require laser treatments, freezing, or surgery to keep your retina in place.

- Diabetes can cause a multitude of visual changes. Progression of the disease can lead to proliferative or non-proliferative diabetic retinopathy. Diabetic patients with tight control of their blood glucose levels can significantly decrease their risk of developing diabetic retinopathy 8. However, the majority of patients will develop diabetic retinopathy after 15 years with the disease 9. Non-proliferative diabetic retinopathy is characterized by microaneurysms, dot-and-blot hemorrhages, hard exudates, cotton-wool spots, and macular edema. Patients with macular edema will commonly present with a decrease in visual acuity 10. However, most patients will remain asymptomatic until they reach the proliferative phase. Proliferative diabetic retinopathy occurs when the prolonged ischemia to the retina triggers new vessel and fibrous tissue formation. The new fibrous growth forms a contracted scar at the vitreoretinal interface and can cause photopsias as the tissue contracts. This contraction can lead to tractional retinal detachments with a potential vitreous hemorrhage due to these new vessels being fragile 11. Patients with tractional retinal detachments may report floaters, photopsias, and/or a curtain over their visual field that is similar to rhegmatogenous retinal detachments. The complications of proliferative diabetic retinopathy can result in permanent vision loss. In a small study, patients with hypoglycemia who were insulin-dependent diabetics reported bilateral photopsias that ceased when their glucose returned to normal levels. They occurred in either light or dark settings and were described as white flickers or circles 1.

- Vertebrobasilar insufficiency. Vertebral basilar insufficiency causes reduced blood flow to the back of the brain can cause a lot of brain damage, and is associated with aging. This decreased blood flow causes ischemia to this area and leads to bilateral photopsias, which are described as broken flashes lasting seconds to minutes 12. The back of the brain is involved in processing visual images and coordinating balance and movement. When this area is damaged, you may also experience weakness, trouble walking, vertigo, dizziness, diplopia, blindness, weakness, ataxia and difficulty making movements happen together 12. Patients may have similar flashes of light and fogging of vision, similar to a visual migraine; however, these symptoms do not continue for as long and do not occur before a headache 6.

- Release Hallucinations (Charles Bonnet Syndrome). Release hallucinations are characterized as visual hallucinations resulting from damage to the visual pathway, unilaterally or bilaterally, in individuals with intact cognition 10. Patients describe seeing multi-colored shapes, grids, faces, people, and flowers lasting from seconds to minutes 1. The underlying mechanism is poorly understood. The most widely accepted theory is the sensory deprivation theory, which states that the loss of visual stimuli to the visual cortex increases the excitability of neurons. This increased neuronal activity leads to random firing of the neurons with little to no stimuli, hence the name release hallucinations [15]. This is supported by the high prevalence in individuals with poorer visual acuity and after postoperative eye patching 13. The prevalence of Charles Bonnet Syndrome increases in individuals with poorer visual acuity bilaterally 14.

- Cancer-Associated Retinopathy. Cancer-associated retinopathy is rare autoimmune disease where the body develops autoantibodies to retinal antigens 15. Recoverin and a-enolase are the most common retinal antigens to which autoantibodies develop 16. These antibodies typically develop in the presence of malignancy, most frequently small cell lung cancer [18-20]. Patients who develop this disease often present with a decrease in visual acuity secondary to photoreceptor dysfunction. Individuals may experience photosensitivity, increased glare after light exposure, decrease in color vision, and/or central scotomas and sausage-shaped arcuate (Bjerrum) scotomas due to cone dysfunction. Night blindness, peripheral ring scotomas, or a significant decline in peripheral vision can be seen with rod dysfunction 17. Photopsias are also seen with cancer-associated retinopathy approximately 7-15% of the time. They are described as flickering or shimmering lights and are thought to be caused by retinal degeneration. One study found that visual symptoms may proceed a cancer diagnosis 18.

- Phosphenes. Phosphenes are a positive photopsia that are seen without a light source 19. They are described as flashes of light, bars/spots of light, or colored spots. These can be elicited by rubbing the eyes, coughing, head trauma, or from other pathological causes. Production of phosphenes by these mechanisms is thought to be due to excitation the photoreceptors in the retina through mechanical pressure 20. The other underlying mechanisms vary depending on the pathology seen within the eye. Retinal traction, retinal detachments, cancer-associated retinopathy, and release hallucination are all pathological causes of phosphenes and occur as discussed above. Phosphenes are also experienced with substance intoxications or irradiation to the eye 21.

- Positive and negative dysphotopsias.

- Positive and negative dysphotopsias are common occurrences following cataract extraction with placement of an intraocular lens. The typical description given of positive dysphotopsias are flashes of light, glare, or halos present in the periphery 22. These occur when the eyes are open and vary in different settings of light, most commonly occurring when an individual enters a lighted room from the dark when the pupils are dilated. These are in contrast to photopsias due to vitreous traction, which are typically elicited in the dark and triggered via movements of the eye. Unlike retinal detachments, positive dysphotopsias are not persistent and do not increase in size [29]. The underlying mechanism of positive dysphotopsias is the result of aberrant reflections of light off the edge of the intraocular lens 22.

- In contrast, negative dysphotopsias are commonly described as arcs, or crescent-shaped, shadows in the periphery 22. The underlying mechanism of negative dysphotopsias is due to the fraction of light that reflects away from the eye causing a small area in which light does not reach the retina 23. Negative dysphotopsias commonly resolve when the patient is dilated. Both positive and negative dysphotopsias are more common with small sharp-edged intraocular lens 24. Multifocal IOLs (intraocular lens) are also associated with an increase in glare and photopsias when compared to monofocal intraocular lens 25. These symptoms are most common in the early post-operative period but typically subside as the capsule undergoes fibrosis 22. Although relatively infrequent, some patients may find these distracting enough to require repositioning or secondary placement of the intraocular lens.

Photopsia symptoms

Photopsias are flashes of light that are usually brief and intermittent 1.

Photopsias usually appear as:

- flickering lights

- shimmering lights

- floating shapes

- moving dots

- snow or static

Photopsia treatment

Photopsia treatment involves treating the underlying cause.

References- Photopsias: A Key to Diagnosis. Ophthalmology. 2015 Oct;122(10):2084-94. doi: 10.1016/j.ophtha.2015.06.025. Epub 2015 Aug 3. https://doi.org/10.1016/j.ophtha.2015.06.025

- Aminoff MJ, Greenberg DA, Simon RP. Headache & Facial Pain. Clinical Neurology, 9e. New York, NY: McGraw-Hill Education; 2015.

- Vincent MB. Vision and migraine. Headache 2015;55(4):595-599. DOI: 10.1111/head.12531

- Marzoli SB, Criscuoli A. The role of visual system in migraine. Neurol Sci 2017;38(Suppl 1):99-102. DOI: 10.1007/s10072-017-2890-0

- Sharma P, Sridhar J, Mehta S. Flashes and Floaters. Prim Care 2015;42(3):425-435. DOI: 10.1016/j.pop.2015.05.011

- Horton JC. Disorders of the Eye. In: Kasper D, Fauci A, Hauser S, Longo D, Jameson JL, Loscalzo J, editors. Harrison’s Principles of Internal Medicine, 19e. New York, NY: McGraw-Hill Education; 2014.

- Hollands H, Johnson D, Brox AC, Almeida D, Simel DL, Sharma S. Acute-onset floaters and flashes: is this patient at risk for retinal detachment? Jama 2009;302(20):2243-2249. DOI: 10.1001/jama.2009.1714

- Zhao Q, Zhou F, Zhang Y, Zhou X, Ying C. Fasting Plasma Glucose Variability Levels and Risk of Adverse Outcomes Among Patients with Type 2 Diabetes: A Systematic Review and Meta-analysis. Diabetes Res Clin Pract 2018;10.1016/j.diabres.2018.12.010

- Klein R, Klein BE, Moss SE, Davis MD, DeMets DL. The Wisconsin epidemiologic study of diabetic retinopathy. II. Prevalence and risk of diabetic retinopathy when age at diagnosis is less than 30 years. Arch Ophthalmol 1984;102(4):520-526.

- Basic ophthalmology: essentials for medical students. 10th ed: American Academy of Ophthalmology, 2016.

- Masharani U. Diabetes Mellitus & Hypoglycemia. In: Papadakis MA, McPhee SJ, Rabow MW, editors. Current Medical Diagnosis & Treatment 2018. New York, NY: McGraw-Hill Education; 2018.

- Lima Neto AC, Bittar R, Gattas GS, Bor-Seng-Shu E, Oliveira ML, Monsanto RDC, Bittar LF. Pathophysiology and Diagnosis of Vertebrobasilar Insufficiency: A Review of the Literature. Int Arch Otorhinolaryngol 2017;21(3):302-307.

- Beaulieu RA, Tamboli DA, Armstrong BK, Hogan RN, Mancini R. Reversible Charles Bonnet Syndrome After Oculoplastic Procedures. J Neuroophthalmol 2018;38(3):334-336. DOI: 10.1097/wno.0000000000000477

- Pang L. Hallucinations Experienced by Visually Impaired: Charles Bonnet Syndrome. Optom Vis Sci 2016;93(12):1466-1478. DOI: 10.1097/opx.0000000000000959

- Moyer K, DeWilde A, Law C. Cystoid macular edema from cancer-associated retinopathy. Optom Vis Sci 2014;91(4 Suppl 1):S66-70. DOI: 10.1097/opx.0000000000000184

- Grange L, Dalal M, Nussenblatt RB, Sen HN. Autoimmune retinopathy. Am J Ophthalmol 2014;157(2):266-272.e261. DOI: 10.1016/j.ajo.2013.09.019

- Grewal DS, Fishman GA, Jampol LM. Autoimmune retinopathy and antiretinal antibodies: a review. Retina 2014;34(5):827-845. DOI: 10.1097/iae.0000000000000119

- Adamus G. Autoantibody targets and their cancer relationship in the pathogenicity of paraneoplastic retinopathy. Autoimmun Rev 2009;8(5):410-414. DOI: 10.1016/j.autrev.2009.01.002

- Ropper AH, Samuels MA, Klein JP. Chapter 13. Disturbances of Vision. Adams and Victor’s Principles of Neurology, 10e. New York, NY: The McGraw-Hill Companies; 2014.

- Salari V, Scholkmann F, Vimal RLP, Csaszar N, Aslani M, Bokkon I. Phosphenes, retinal discrete dark noise, negative afterimages and retinogeniculate projections: A new explanatory framework based on endogenous ocular luminescence. Prog Retin Eye Res 2017;60:101-119. DOI: 10.1016/j.preteyeres.2017.07.001

- Mathis T, Vignot S, Leal C, Caujolle JP, Maschi C, Mauget-Faysse M, Kodjikian L, Baillif S, Herault J, Thariat J. Mechanisms of phosphenes in irradiated patients. Oncotarget 2017;8(38):64579-64590. DOI: 10.18632/oncotarget.18719

- Bournas P, Drazinos S, Kanellas D, Arvanitis M, Vaikoussis E. Dysphotopsia after cataract surgery: comparison of four different intraocular lenses. Ophthalmologica 2007;221(6):378-383. DOI: 10.1159/000107496

- Davison JA. Positive and negative dysphotopsia in patients with acrylic intraocular lenses. J Cataract Refract Surg 2000;26(9):1346-1355.

- Hu J, Sella R, Afshari NA. Dysphotopsia: a multifaceted optic phenomenon. Curr Opin Ophthalmol 2018;29(1):61-68. DOI: 10.1097/icu.0000000000000447

- Wang SY, Stem MS, Oren G, Shtein R, Lichter PR. Patient-centered and visual quality outcomes of premium cataract surgery: a systematic review. Eur J Ophthalmol 2017;27(4):387-401. DOI: 10.5301/ejo.5000978