What is phytophotodermatitis

Phytophotodermatitis is a skin condition caused by sequential exposure to photosensitizing substances present in plants followed by sunlight or ultraviolet light 1. Several plants (e.g., limes, celery, fig, and wild parsnip) contain furocoumarin compounds (psoralens). Phytophotodermatitis name has 3 components: phyto (plant), photo (light) and dermatitis (inflammatory rash). Phytophotodermatitis generally occurs during in spring or summer following some outdoor activity on a sunny day during which there has been contact with one of the responsible plants. Phytophotodermatitis is usually not itchy (nonpruritic) and has various appearances; it is often asymmetrically distributed and oddly shaped.

Phytophotodermatitis is a clinical diagnosis and should be suspected when patients present with an irregularly shaped rash and exposure to sunlight and a psoralen-containing substance. Diagnosis requires a history of exposure to a psoralen-containing substance and sunlight.

The acute dermatitis is self-limited and resolves over a period of days to weeks, but the ensuing hyperpigmentation, caused by psoralen-stimulated melanin hyperproduction, can last weeks to months 2. Persistent hyperpigmentation is expected and can last weeks to months.

The phytophotodermatitis reaction is highly variable. Rash characteristics can range from simple hyperpigmentation to erythema, vesicles, or bullae 2. The variability is dependent on the quantity of photosensitizing agent, the length of exposure,8 the type of psoralen-containing substance 3 and the method of contact 2. For this reason, scientists might believe the rash has more than one cause. One case report documented a leg rash that was consistent with the shape of the patient’s palm and fingertips 2. The rash has also been confused with nonaccidental trauma 3. Usually, the rash is nonpruritic; pruritus should prompt consideration of other diagnoses 4.

Treatment is sometimes pursued; however, there is limited evidence on efficacy. Severe bullous reactions and resulting wounds should be managed with standard care to prevent secondary infection 5. In some cases, physicians might choose to prescribe topical steroids 4 or antihistamines 4 or advise the use of cold compresses1 for relief of pain or itching. Evidence for these treatments is based on expert opinion. While the rash might be aesthetically disturbing to patients, reassurance is often all that is needed 2.

Patients can be counseled on prevention. If an exposure can be identified early, the chemical stimulus can be cleansed from the skin with water. Psoralen must be absorbed into the skin before activation by UVA light, a process that can take anywhere between 30 and 120 minutes 2. This knowledge might be useful for patients with occupational or travel-related exposures. Not all sunscreens are helpful in preventing the rash, as some sunscreens only protect against UVB light 6.

Phytophotodermatitis causes

Phytophotodermatitis is a rash occurring after contact between the skin and furanocoumarins, a class of chemicals found in many plants and fruits 2. Furocoumarins are beneficial to plants as they protect them from the attack of fungal pathogens 7.

Phytophotodermatitis is induced by the action of long wavelength ultraviolet radiation (UVA) on a plant chemical called furocoumarins (psoralens) on the skin surface. Contact with the plant, fruit or vegetable may have been brief and unnoticed. The reaction depends on:

- The amount of juice or sap on the skin

- The amount of furocoumarins in the plant, which is thought to be produced in response to fungal attack

- Amount of UVA exposure. UVA levels are greater when during the middle part of the day, in midsummer and at high altitude

The reaction causes inflammation in the epidermis (contact dermatitis) and activation of melanocytes (pigment cells) to produce melanin pigment.

Pigmentation due to phytophotodermatitis is partly epidermal melanosis (ie pigment is within the skin cells) and partly dermal melanosis (ie the pigment is deeper in the skin).

The active substance within the furanocoumarins is psoralen 2, which reacts with UVA light to cause an intense cutaneous reaction. Phytophotodermatitis does not involve any immune mechanism but must be differentiated from an allergic response 8. At a histologic level, cell damage is first detectable at 24 hours after the initial insult; clinical signs can be identified 48 hours after UVA exposure 9.

Plants and fruits commonly associated with phytophotodermatitis

The following are commonly associated with phytophotodermatitis 10:

- Bergamot

- Buttercup

- Capsaicin (peppers)

- Celery

- Carrots

- Citrus fruits (especially lemons and limes)

- Common rue

- Dill

- Fennel

- Fig

- Hogweed

- Lemon

- Lime

- Mustard

- Parsley

- Parsnip

- Parsley

- Several species of wild flowers (umbelliferae), such as hogweed.

Photoxicity due to PUVA

Photochemotherapy (PUVA) is a treatment for inflammatory skin diseases such as psoriasis and eczema. The treatment involves taking psoralens by mouth or applying psoralens solution to the skin, followed by exposure to UVA, in controlled circumstances.

PUVA has beneficial effects on the skin diseases, but as it involves the same process as occurs in phytophotodermatitis, it can result in excessive pigmentation. This can be quite noticeable after topical or bathwater PUVA.

Phytophotodermatitis clinical features

During the acute inflammatory stage, itchy blisters and reddened patches appear on exposed skin, usually the forearms or lower legs. These are often irregularly distributed and odd in shape. Linear lesions are characteristic. In some cases, the inflammatory phase is not observed.

After a few days the redness and blistering settles down, but is replaced by unsightly and bizarre pigmentation at the same sites. The pigmentation is more pronounced in dark skin compared to fair skin. This postinflammatory pigmentation may persist for weeks to months.

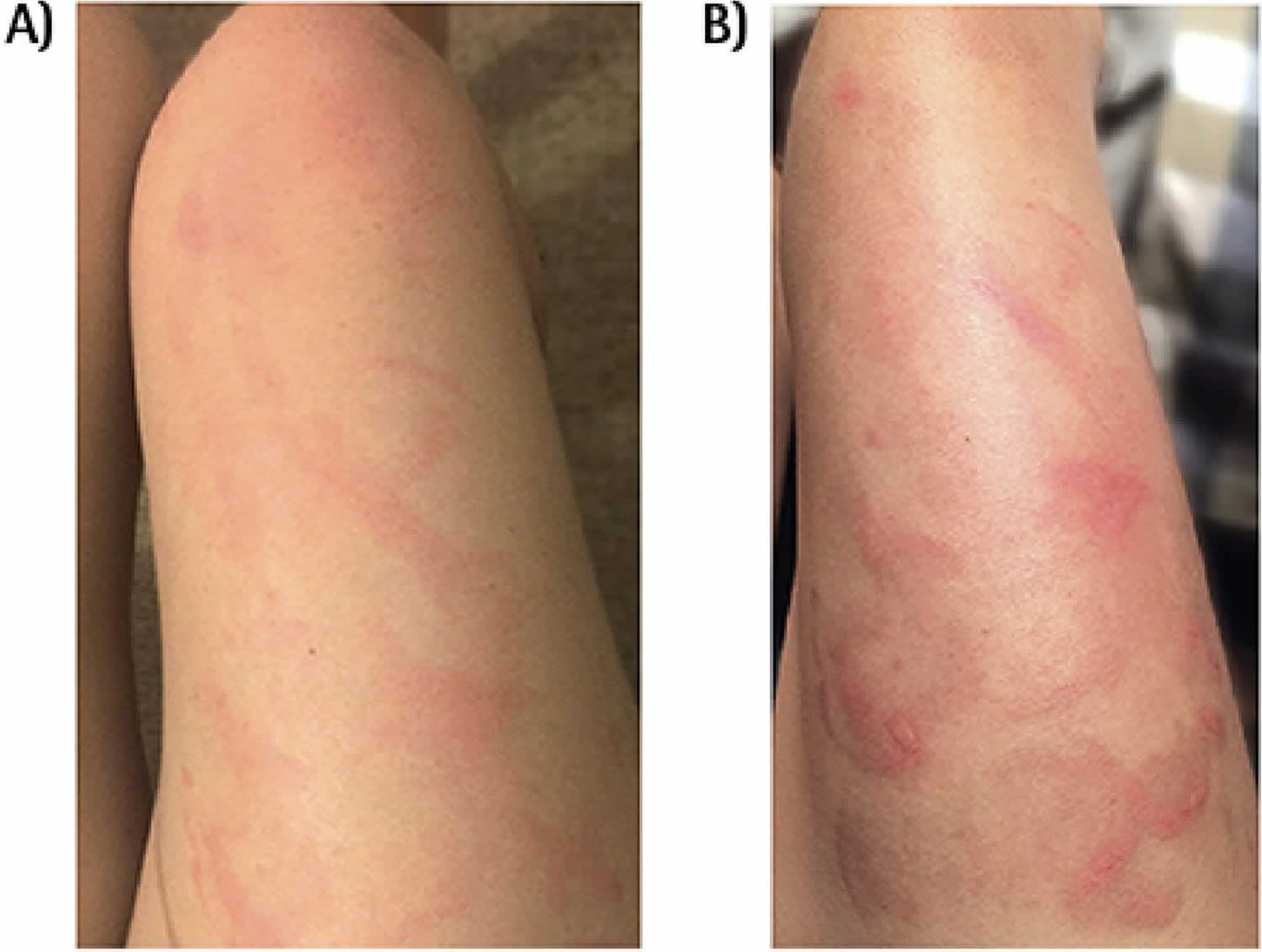

Figure 1. Acute phytophotodermatitis

Footnote: Patient’s right thigh: A) Early erythematous rash; B) vesicles and bullae.

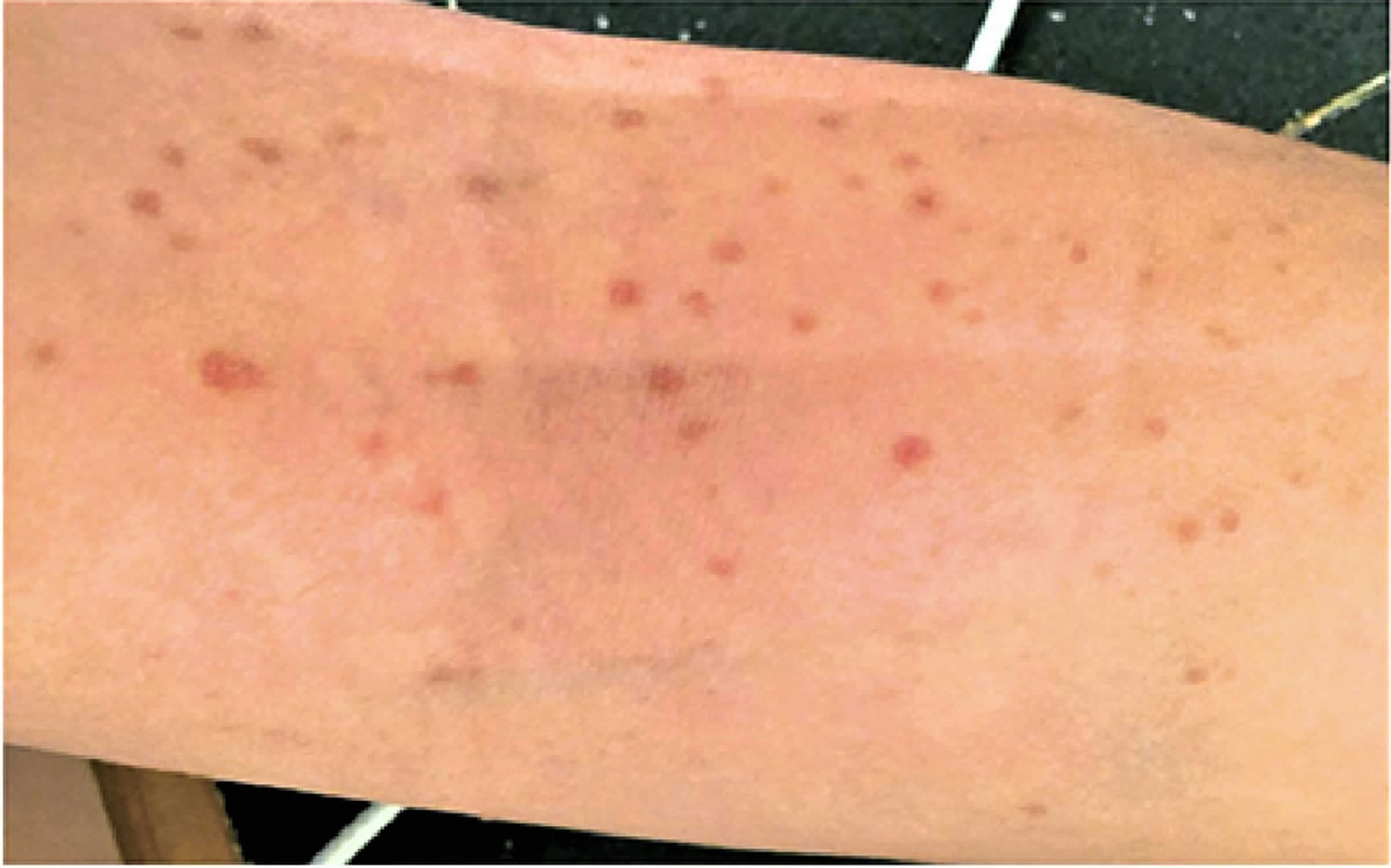

Figure 2. Acute phytophotodermatitis macular rash

Footnote: Macular rash seen on the patient’s right antecubital fossa.

Figure 3. Phytophotodermatitis hyperpigmentation

Footnote: Phytophotodermatitis hyperpigmentation on the patient’s right thigh following the acute rash.

Phytophotodermatitis treatment

By the time pigmentation has occurred, the inflammatory phase of phytophotodermatitis is over. This means that anti-inflammatory treatments like topical steroids are only useful in the early phase of redness and blistering. In some cases, physicians might choose to prescribe topical steroids 4 or antihistamines 4 or advise the use of cold compresses1 for relief of pain or itching. Evidence for these treatments is based on expert opinion. While the rash might be aesthetically disturbing to patients, reassurance is often all that is needed 2.

The postinflammatory pigmentation that follows phytophotodermatitis responds poorly to treatment with bleaching creams. It fades gradually over weeks to months. Using covering clothing and broad spectrum sunscreens, affected skin should be protected from further sun exposure, which might cause the pigmentation to darken. It can be disguised using cosmetic camouflage make-up.

Phytophotodermatitis healing time

The acute dermatitis is self-limited and resolves over a period of days to weeks, but the ensuing hyperpigmentation, caused by psoralen-stimulated melanin hyperproduction, can last weeks to months 2. Persistent hyperpigmentation is expected and can last weeks to months.

References- Son JH, Jin H, You HS, et al. Five Cases of Phytophotodermatitis Caused by Fig Leaves and Relevant Literature Review. Ann Dermatol. 2017;29(1):86–90. doi:10.5021/ad.2017.29.1.86 https://www.ncbi.nlm.nih.gov/pmc/articles/PMC5318534

- Moreau JF, English JC III., Gehris RP. Phytophotodermatitis. J Pediatr Adolesc Gynecol 2014;27(2):93-4.

- Carlsen K, Weismann K. Phytophotodermatitis in 19 children admitted to hospital and their differential diagnoses: child abuse and herpes simplex virus infection. J Am Acad Dermatol 2007;57(5 Suppl):S88-91.

- Wynn P, Bell S. Phytophotodermatitis in grounds operatives. Occ Med (Lond) 2005;55(5):393-5.

- Mioduszewski M, Beecker J. Phytophotodermatitis from making sangria: a phototoxic reaction to lime and lemon juice. CMAJ 2015;187(10):756.

- Deleo VA. Photocontact dermatitis. Dermatol Ther 2004;17(4):279-88.

- Photoallergic contact dermatitis to 8-methoxypsoralen in Ficus carica. Bonamonte D, Foti C, Lionetti N, Rigano L, Angelini G. Contact Dermatitis. 2010 Jun; 62(6):343-8.

- Jorge VM, Almedia HL Jr., Amado M. Serial light microscopy of experimental phytophotodermatitis in animal model. J Cutan Pathol 2009;36(3):338-41. Epub 2008 Nov 19.

- Weber IC, Davis CP, Greeson DM. Phytophotodermatitis: the other “lime” disease. J Emerg Med 1999;17(2):235-7.

- Phytophotodermatitis. Jamie Harshman, Yi Quan, Diana Hsiang. Canadian Family Physician Dec 2017, 63 (12) 938-940. https://www.cfp.ca/content/63/12/938