What is preauricular sinus

Preauricular pit is also known as preauricular cyst, preauricular sinus or preauricular fissure. A preauricular ear pit is essentially a preauricular sinus tract traveling under your skin that doesn’t belong there; it’s marked by a tiny opening to the preauricular sinus tract, right in front of your ear and above your ear canal. In atypical cases, the opening appears below your ear canal, closer to the lobe. Preauricular sinus is usually asymptomatic unless it is infected.

A preauricular pit’s tract running underneath the skin can be either short or long and convoluted, with extensive branching. It’s more common for only one ear to have a preauricular pit.

Preauricular pits are congenital, meaning children are born with this malformation when ear development goes awry early in gestation. However, the malformation is not associated with hearing impairments, and only rarely associated with a genetic syndrome involving other problems. A baby born with a preauricular pit will be examined for other abnormalities to rule out these syndromes.

Developmentally, the external ear develops from six eminences on the mandibular and hyoid margin of the first external groove. Failure of the tubercles to fuse with each other or failure of some of these tubercles (hillock) to grow normally may produce a variety of external ear malformation such as congenital preauricular sinus 1.

Preauricular sinus or preauricular pit occurs with different prevalent rates among blacks and Caucasians. In different parts of the world, the prevalence varies, in the USA it is 0.1-0.9%, England is 0.9%, Taiwan is 1.6-2.5%, among Asian, it occurs in 4-6% of the population and some parts of Africa it is 4-10% 2.

The main problem with preauricular pits, if they appear in an otherwise healthy child, is that they can lead to benign cysts or infections, including small pus-filled masses known as abscesses (see Figure 3). When a child gets repeat infections, a surgeon may recommend complete removal of the pit. Otherwise, if the pit poses no chronic problems, it may be left alone.

Preauricular pits are different from preauricular tags, which are fleshy knobs of skin in front of the ears without an attached sinus tract. Tags pose only a cosmetic problem and not a risk of infection like pits do.

On the other hand, preauricular pits are less serious thanand must be differentiated from – a branchial cleft cyst. A branchial cleft cyst, which may appear as a small opening, skin tag, or dimpling on the side of the neck can become infected and drain fluid. All such malformations of the outer ear, when taken together, occur in less than 1 percent of otherwise healthy babies. They are considered a common congenital defect, even if the occurrence rate sounds low. Boys and girls are equally affected by outer ear malformations. And although these malformations don’t necessarily run in the family, when both ears are affected, a family history is more likely.

Figure 1. Preauricular pit

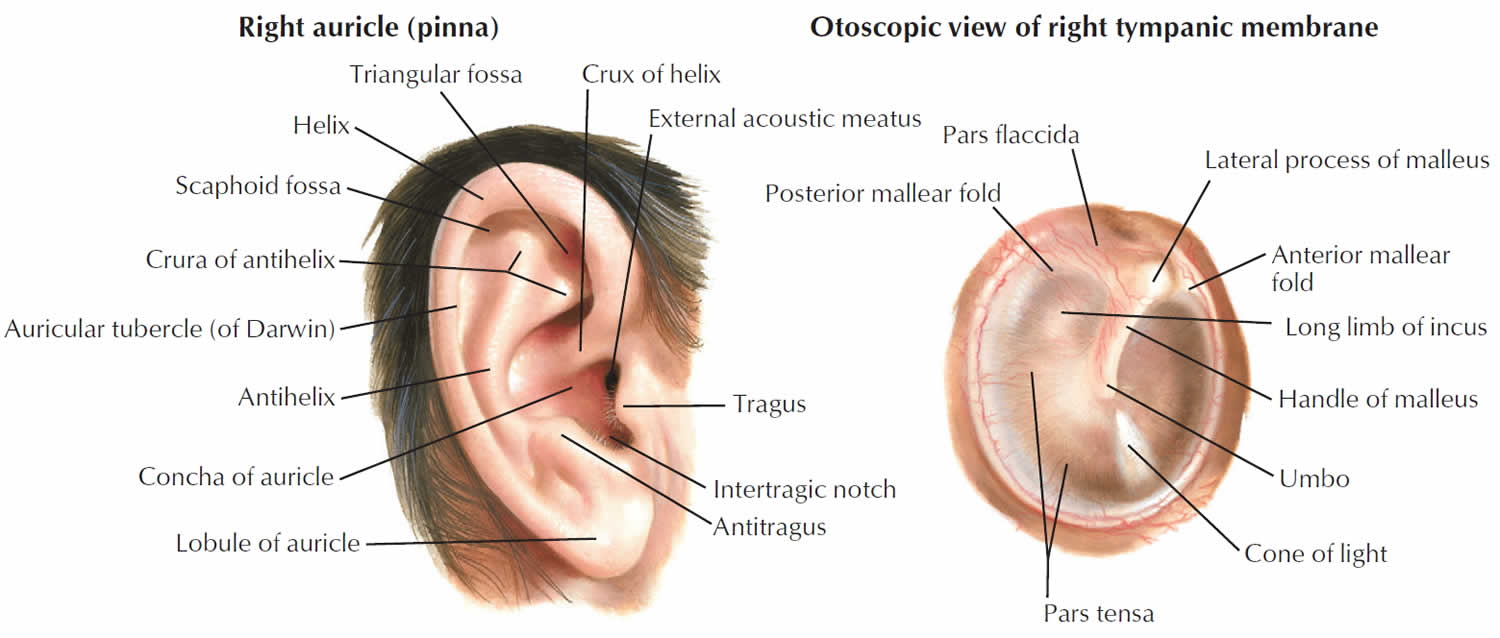

Figure 2. Human ear anatomy

Figure 3. Preauricular sinus abscess

What causes preauricular sinus?

During embryogenesis, the auricle arises from the first and second branchial arches during the sixth week of gestation. Branchial arches are mesodermal structures covered by ectoderm and lined with endoderm. These arches are separated from each other by ectodermal branchial clefts externally and by endodermal pharyngeal pouches internally. The first and second branchial arches each give rise to 3 hillocks; these structures are called the hillocks of His. Three hillocks arise from the caudal border of the first branchial arch, and 3 arise from the cephalic border of the second branchial arch. These hillocks should unite during the next few weeks of embryogenesis. Preauricular sinuses are thought to occur as a result of incomplete fusion of these hillocks.

Preauricular sinuses are usually narrow, they vary in length (usually they are short), and their orifices are usually minute. They may arborize and follow a tortuous course in the immediate vicinity of the external ear. The preauricular sinuses are usually found lateral, superior, and posterior to the facial nerve and the parotid gland. In almost all cases, the duct connects to the perichondrium of the auricular cartilage. They can extend into the parotid gland.

Congenital periauricular fistulas may be seen as variations of preauricular sinuses 3.

Embryology and branchial arch development

The auricle forms during the sixth week of gestation. The first and second branchial arches give rise to a series of 6 mesenchymal proliferations known as the hillocks of His, which fuse to form the definitive auricle. The first arch gives rise to the first 3 hillocks, which form the tragus, helical crus, and the helix. The second arch gives rise to the second 3 hillocks, which form the antihelix, scapha, and the lobule.

Defective or incomplete hillock fusion during auricular development is postulated as the source of the preauricular sinus. Another theory suggests that localized folding of ectoderm during auricular development is the cause of preauricular sinus formation. The first 3 hillocks are most often linked to supernumerary hillocks, leading to preauricular tag formation.

Genetics

Correct sequential gene activation is required for normal ear and facial development. Interrupting the gene activation sequence in laboratory animals disrupts ear development.

Genetic linkage analysis studies have suggested that congenital preauricular sinus localizes to chromosome 8q11.1-q13.3 4.

The inner neurological hearing apparatus, cochlea, and auditory nerve form in conjunction with the outer ear structures during the early developmental stages. External deformities may be associated with an inner neurological deformity and, hence, suggest a possible deafness.

Associated syndromes

Syndromic expression of pits, tags, and fissures occurs at much higher frequencies in certain craniofacial dysmorphisms. Minor anomalies of the head and neck may aid the clinician in developing a presumptive diagnosis during the initial examination. Additional ear anomalies include helical fold abnormalities, asymmetry, posterior angulation, small size, absent tragus, and narrow external auditory meatus. Some syndromes with characteristic ear anomalies are as follows:

- Branchiootorenal syndrome – Preauricular sinus

- Beckwith-Wiedemann syndrome – Preauricular sinus with asymmetric earlobes

- Mandibulofacial dysostosis – Auricular pits/fistulas

- Oculoauriculovertebral dysplasia – Preauricular tags

- Chromosome arm 11q duplication syndrome – Preauricular tags or pits

- Chromosome arm 4p deletion syndrome – Preauricular dimples or skin tags

- Chromosome arm 5p deletion syndrome – Preauricular tags

A study by Beleza-Meireles et al of clinical phenotypes in 51 patients with oculoauriculovertebral dysplasia found ear abnormalities in 47 (92%) of them (unilateral: 24 patients; bilateral: 23 patients) 5.

Medication

A study by Andersen et al 6 suggested that the occurrence of birth defects in the face and neck region, including preauricular cysts, may be linked to the use of propylthiouracil in early pregnancy to treat maternal hyperthyroidism. In a review of records from more than 1.6 million children born in Denmark between 1996 and 2008, the investigators concluded that in terms of having a birth defect in the head or neck region—specifically, a preauricular or branchial sinus, fistula, or cyst—children exposed to propylthiouracil had a hazard ratio of 4.92. These same children also had an hazard ratio of 2.73 for a urinary system birth defect (single renal cyst, hydronephrosis). Possible propylthiouracil-related birth defects were found in a total of 14 children, including three whose mothers were initially given methimazole/carbimazole but were switched to propylthiouracil in early pregnancy 6.

Preauricular sinus signs and symptoms

Children with a preauricular sinus or preauricular pit don’t always have the same set of symptoms. Some also have a syndrome associated with their pit. The most common symptoms of a preauricular pit by itself and in conjunction with a syndrome include:

- A visible tiny opening in front of one or both ears.

- An opening that appears as more of a dimpling.

- Swelling, pain, fever, redness or pus in and around the pit, signaling an infection, such as cellulitis or an abscess. Clinical presentations of preauricular sinus abscess are usually recurrent ear discharge, pain, swelling, itching, headache and fever. Other congenital anomalies such as hearing loss or renal problem of 1.7% and 2.6% respectfully are usually associated with preauricular sinus 7. Preauricular sinus abscess is commonly mistaken for pimples (blackheads), furunculosis, chronic infection such as tuberculosis and fungal also congenital condition such as dermoids and sebaceous cysts 8.

- A slow-growing painless lump right next to the opening, signaling a cyst. A cyst also raises the risk of infection.

Preauricular sinuses are prone to infection leading to preauricular sinus abscess, when it infected, it is mainly by Staphylococcus aureus and less commonly by Streptococcus and Proteus 9. These results in irritation, fluid drainage, edema, pain and when the sinus ostium is blocked pus accumulate leading to abscess formation. It may also be complicated by spreading to contiguous structures such as the pinna, temporomandibular joint and external auditory canal.

Associated syndromes

- Asymmetric earlobes and an abnormally large tongue in addition to pits in front of the ears can be a sign of Beckwith-Wiedemann syndrome. This syndrome is associated with abdominal abnormalities and kidney and liver cancers.

- Holes or pits in the side of the neck, pits and/or tags in front of the ear, hearing loss, and kidney abnormalities can all be a sign of branchio-oto-renal syndrome.

Preauricular sinus complications

A preauricular sinus is lined with skin cells and can get blocked and infected at any time. Infection can lead to abscess formation and cellulitis.3

The signs of an infected preauricular pit are redness, pain, fever, swelling, and/or yellowish, thick discharge. Infected preauricular pits need to be treated by a physician with antibiotics and sometimes incision and drainage of the pus-filled collection.

A pit can also accumulate material and become a cyst—a painless lump near the pit.

Preauricular sinus diagnosis

A preauricular pit may go unnoticed at birth. Whether you or your primary care provider first notices the tiny hole, the next step is to see an otolaryngologist (ENT doctor or ear, nose and throat specialist). An otolaryngologist can perform the proper evaluation of the pit and any associated risks. During the course of the evaluation, the otolaryngologist may:

- Rule out various genetic syndromes that cause abnormalities of the face and head; some syndromes cause more severe abnormalities with the ear, including folded or asymmetrical ears, and hearing loss as well. Sometimes, these additional abnormalities can be very mild and hardly noticeable, but a specialist’s careful eye can recognize them.

- Examine your child’s pits and look for signs of cysts or infection.

- Perform imaging, such as a CT scan or MRI with contrast, in cases where the pit is in an atypical location, such as below the external auditory canal (closer to the lobe); this can be signaled by frequent swelling. Imaging is also generally recommended when pits appear with other outer-ear abnormalities.

- Perform imaging to help the doctor differentiate cysts and abscesses

- Perform an ultrasound of the kidneys if your child has preauricular pits and a branchial cleft cyst, to rule out branchio-oto-renal syndrome

- Perform an audiogram if the pits are associated with other outer-ear deformities. Pits by themselves don’t usually require a hearing test. In addition, most newborns in the U.S. undergo auditory screening at birth. Confirmation of normal hearing is recommended for children with ear deformities in addition to pits.

- Refer your child to appropriate specialists if he has organ system abnormalities or other syndromic features.

Preauricular sinus treatment

An otolaryngologist is the best type of specialist to recommend and perform treatment for a preauricular pit since treatment can vary according to a complex set of factors. In addition, if the sinus tract ultimately requires surgical removal, the tract might be lengthy and convoluted and best left to the most experienced hands. Possible treatment approaches include:

- Leaving a pit alone if it doesn’t become infected.

- Prescribing your child oral antibiotics if the pit shows the earliest signs of infection, including redness and swelling.

- Performing needle aspiration on a difficult infection known as an abscess, if it fails to respond to antibiotics. The doctor may “culture,” or examine, the bacteria extracted from the pus.

- Performing incision and drainage if the abscess fails to respond to needle aspiration.

- Surgically removing the entire tract if the pit is prone to recurrent infections. The procedure is done under general anesthesia and may take up to an hour; it can be done in an outpatient facility. A surgeon will usually postpone surgery until after an infection and residual inflammation are cleared up. Pits behind the external auditory canal require two incisions to remove the tract completely.

Follow-up care

If your child has been treated for an infection in his preauricular pit, he will be followed closely. Repeat infections will require surgery.

If your child does have surgery to remove his pit, he can usually go to an outpatient facility for this procedure and be sent home the same day. The doctor and nurse will recommend wound care for the bandaged area, prescribe antibiotics, and schedule a follow-up appointment. Sutures will dissolve on their own. Your child will need to keep his head elevated at night for about a week and avoid showering until the bandage is removed. He can usually return to school within the week but will have to avoid strenuous activity for several weeks.

Preauricular sinus prognosis

A child with a preauricular pit by itself is usually otherwise healthy. Often, people hardly notice a pit or, if it’s close enough to the ear, may mistake it for an ear piercing. A preauricular pit can be left alone unless it poses a risk of recurrent infection or cysts. In that case, surgery can successfully remove the entire pit and your child will have no further problems associated with it.

References- The preauricular sinus: a review of its clinical presentation, treatment, and associations. Scheinfeld NS, Silverberg NB, Weinberg JM, Nozad V. Pediatr Dermatol. 2004 May-Jun; 21(3):191-6.

- Adegbiji WA, Alabi BS, Olajuyin OA, Nwawolo CC. Presentation of preauricular sinus and preauricular sinus abscess in southwest Nigeria. Int J Biomed Sci. 2013;9(4):260–263. https://www.ncbi.nlm.nih.gov/pmc/articles/PMC3884798

- Kim JR, Kim do H, Kong SK, Gu PM, Hong TU, Kim BJ, et al. Congenital periauricular fistulas: possible variants of the preauricular sinus. Int J Pediatr Otorhinolaryngol. 2014 Nov. 78(11):1843-8.

- Zou F, Peng Y, Wang X, et al. A locus for congenital preauricular fistula maps to chromosome 8q11.1-q13.3. J Hum Genet. 2003. 48(3):155-8.

- Beleza-Meireles A, Hart R, Clayton-Smith J, et al. Oculo-auriculo-vertebral spectrum: Clinical and molecular analysis of 51 patients. Eur J Med Genet. 2015 Sep. 58 (9):455-65.

- Andersen SL, Olsen J, Wu CS, et al. Severity of Birth Defects After Propylthiouracil Exposure in Early Pregnancy. Thyroid. 2014 Jun 25.

- The preauricular sinus: A review of its aetiology, clinical presentation and management. Tan T, Constantinides H, Mitchell TE. Int J Pediatr Otorhinolaryngol. 2005 Nov; 69(11):1469-74.

- The preauricular sinus: factors contributing to recurrence after surgery. Yeo SW, Jun BC, Park SN, Lee JH, Song CE, Chang KH, Lee DH. Am J Otolaryngol. 2006 Nov-Dec; 27(6):396-400.

- HERV-mediated genomic rearrangement of EYA1 in an individual with branchio-oto-renal syndrome. Sanchez-Valle A, Wang X, Potocki L, Xia Z, Kang SH, Carlin ME, Michel D, Williams P, Cabrera-Meza G, Brundage EK, Eifert AL, Stankiewicz P, Cheung SW, Lalani SR. Am J Med Genet A. 2010 Nov; 152A(11):2854-60.