Radical cystectomy

Radical cystectomy is a surgery to remove all of the urinary bladder (the organ that holds urine) as well as nearby lymph nodes, tissues and organs. In men, the prostate is removed with the bladder, and in women, the womb, Fallopian tubes, ovaries, and part of the vagina are usually removed 1. When the bladder must be removed, urinary drainage has to be re-established and this is done either by formation of a urinary stoma (ileal conduit) or bladder reconstruction, this is called urinary diversion 1. With incontinent urinary diversion, urine drains through a hole in your abdomen into a bag. Continent urinary diversion involves creating an internal storage for urine. Radical cystectomy is the treatment of choice for patients with muscle-invasive bladder cancer (bladder cancer invades the muscle wall) or when superficial cancer involves a large part of the bladder 2 or recurrent non-muscle invasive bladder cancer 3. Sometimes, when the cancer has spread outside the bladder and cannot be completely removed, surgery to remove only the bladder may be done to reduce urinary symptoms caused by the cancer.

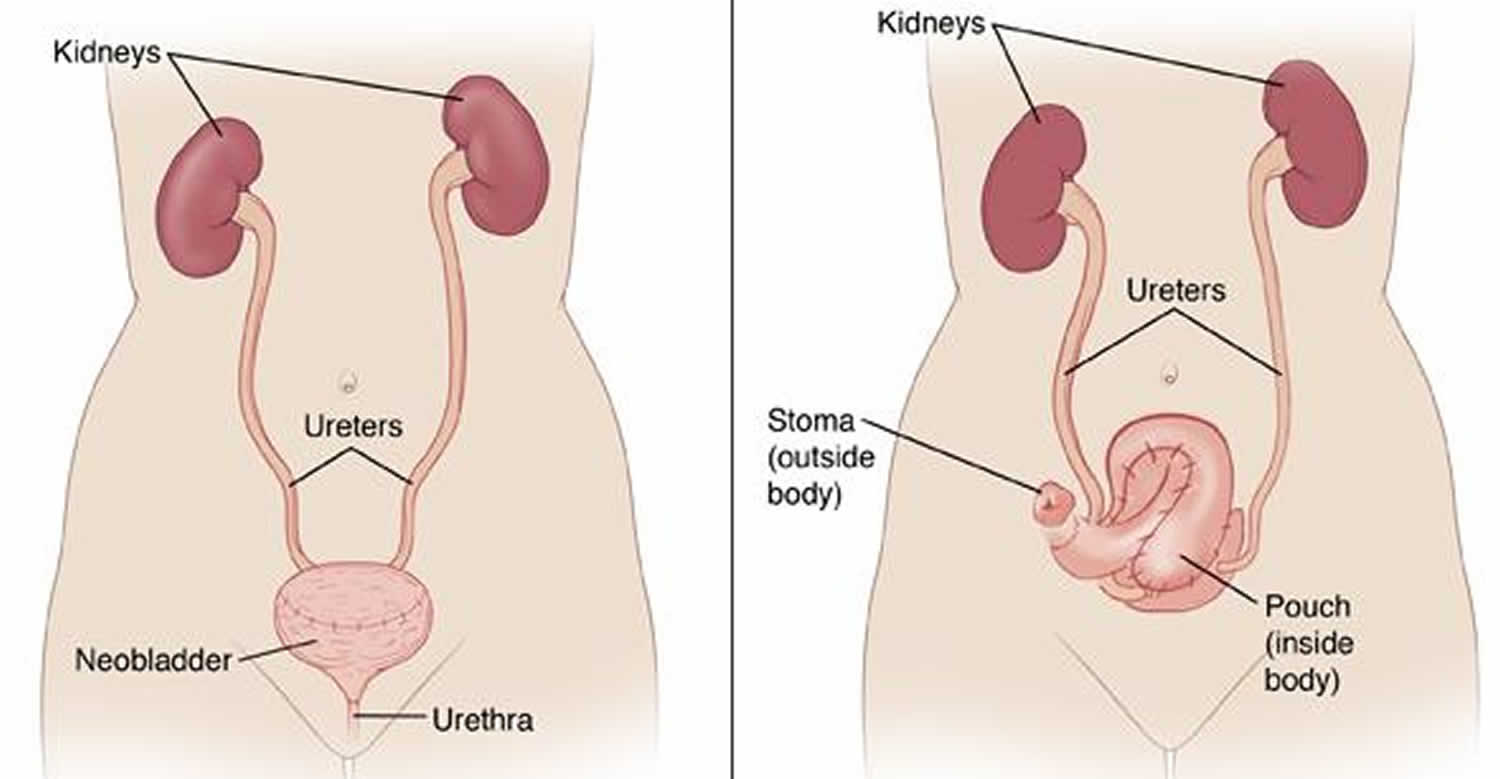

If you have a radical cystectomy, your doctor will create a new way for you to pass urine. There are a few ways this can be done.

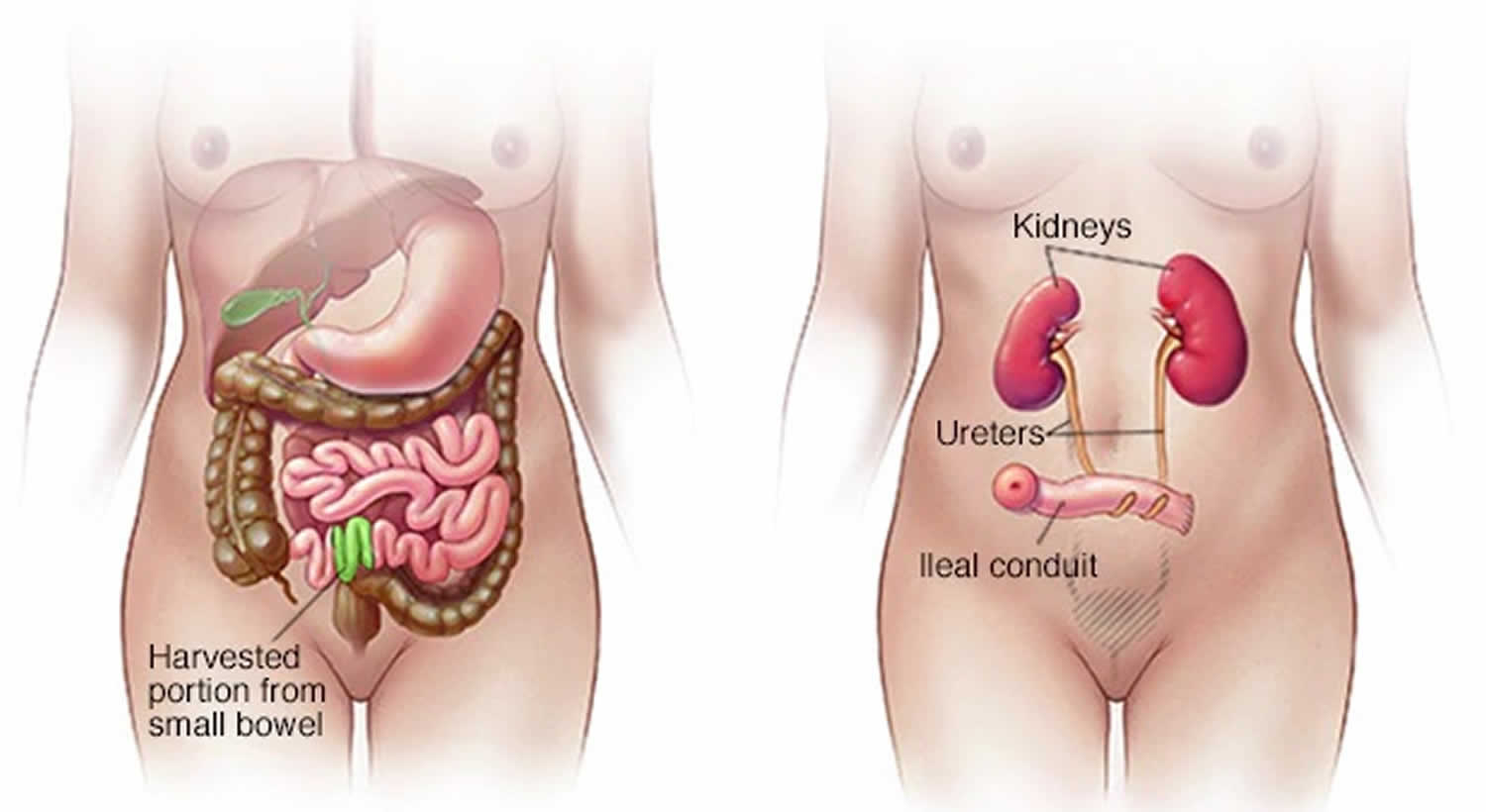

- An ileal conduit. During this procedure, your surgeon uses a piece of your small intestine (ileum) to create a tube that attaches to the ureters and connects your kidneys to an opening in your abdominal wall (stoma). Urine flows from the opening continuously. After surgery, the urine will pass from the ureters through the tube. Then it goes out the opening into a plastic bag. The bag you wear on your abdomen sticks to your skin and collects urine until you drain it.

- A continent reservoir uses a piece of your bowel to make a storage pouch. It is attached inside your pelvis. There are two types of storage pouches. Both types let you control when you pass urine. You may have a:

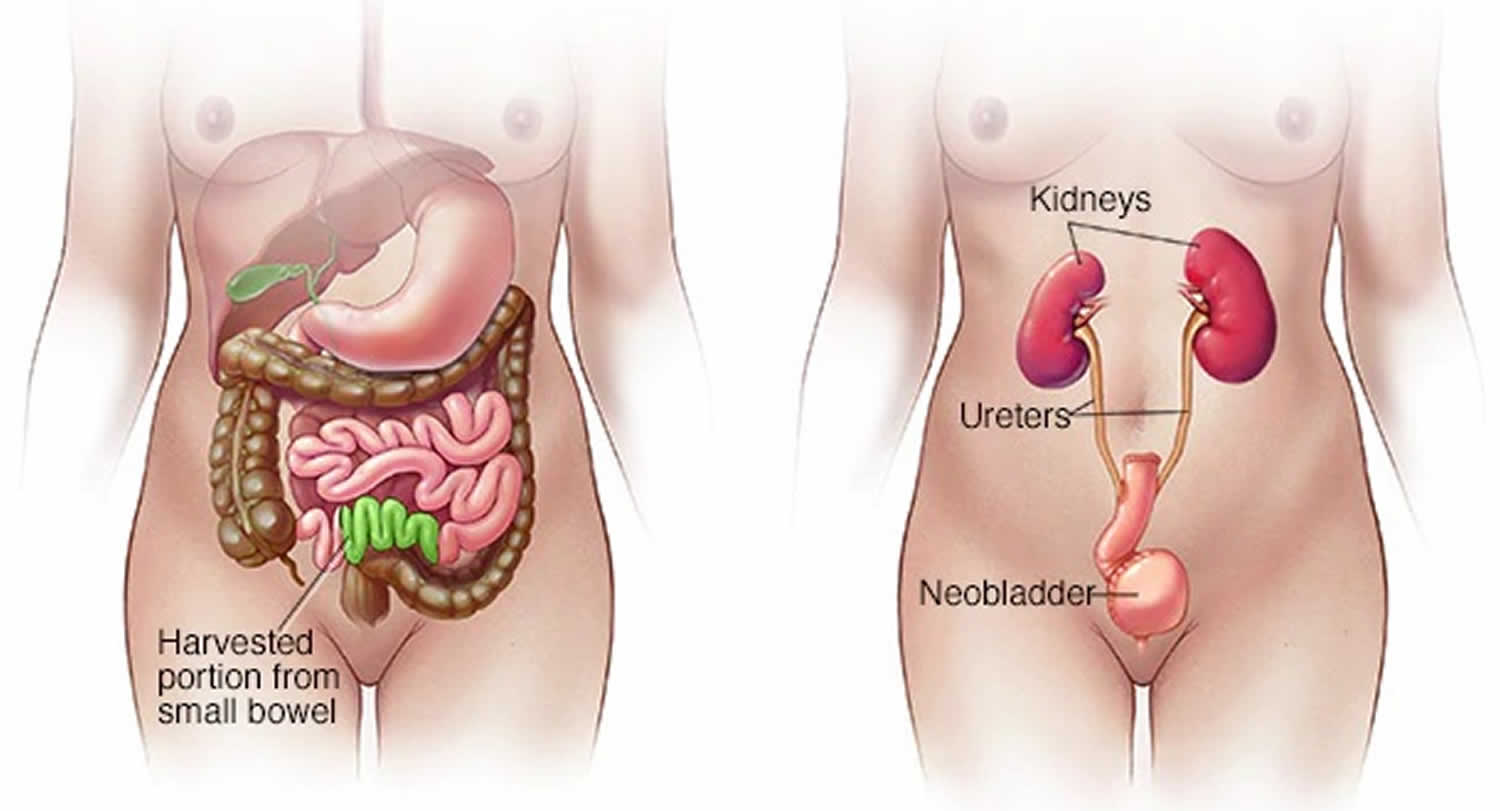

- Bladder substitution reservoir also called a neobladder. During creation of a neobladder, your surgeon uses a slightly larger piece of your small intestine than the one used for an ileal conduit to create a sphere-shaped pouch that becomes your new bladder. Your surgeon places the neobladder in the same location inside your body as your original bladder and attaches the neobladder to the ureters so that urine can drain from your kidneys. The other end of the neobladder is attached to your urethra, allowing you to urinate in a relatively normal fashion. A neobladder isn’t a completely new, normal bladder. If you have this surgery, you might need to use a catheter to help better empty the neobladder. Also, some people experience urinary incontinence surgery. If your urethra was not removed, the storage pouch will attach to your ureters at one end and to your urethra at the other. This lets you pass urine much like you did before surgery.

- Continent diversion reservoir with stoma also called a urostomy. During this procedure, your surgeon uses a piece of your intestine to create a small reservoir inside your abdominal wall. As you make urine, the reservoir fills and you use a catheter to drain the reservoir several times a day. With this type of urinary diversion, you avoid the need to wear a urine collection bag on the outside of your body. But you’ll need to use a long, thin tube (catheter) several times a day to drain the internal reservoir. Leakage from the catheter site may cause some problems or the need to return to the operating room for revision surgery. If all or part of your urethra was removed, the storage pouch will connect your ureters to an opening the doctor makes in your belly. You will put a thin plastic tube called a catheter through the opening to let out the urine.

The goal of urinary diversion is to facilitate the safe storage and timely elimination of urine after your bladder has been removed, while preserving your quality of life.

Talk with your doctor to understand what’s involved with each of these urinary diversion options so that you can choose the one that’s best for you.

Figure 1. Radical cystectomy and ileal conduit

Figure 2. Radical cystectomy with neobladder

Most of the time, radical cystectomy is done through a cut (incision) in the belly (abdomen) also known as open radical cystectomy. You’ll need to stay in the hospital for about a week after the surgery. You can usually go back to your normal activities after several weeks.

In some cases, the surgeon may operate through many smaller incisions using special long, thin instruments, one of which has a tiny video camera on the end to see inside your body. This is called laparoscopic, or “keyhole” surgery. The surgeon may either hold the instruments directly or may sit at a control panel in the operating room and use robotic arms to do the surgery (sometimes known as a robotic cystectomy). This type of surgery may result in less pain and quicker recovery because of the smaller cuts. But it hasn’t been around as long as the standard type of surgery, so it’s not yet clear if it works as well.

It’s important that any type of cystectomy be done by a surgeon with experience in treating bladder cancer. If the surgery is not done well, the cancer is more likely to come back.

Muscle invasive bladder cancer is a cancer that starts in the inside layer of the bladder. Over time, it spreads into the thick muscle deep in the bladder wall. The cancer may then spread to tissue and organs beside the bladder and later to other parts of the body. Muscle invasive bladder cancer is a more harmful kind of bladder cancer than non-muscle invasive bladder cancer. It should be treated without delay.

Your best chance for healing from muscle invasive bladder cancer is early diagnosis and early care. Your care will depend on the stage and how far your cancer has grown. Treatment also depends on your health and age. Your team of healthcare providers will be your urologist, and also may include an oncologist (cancer specialist), radiologist, dietician and counselors. You will likely have a choice of two types of ways to treat your muscle invasive bladder cancer:

- Cystectomy (bladder removal) with or without chemotherapy

- Chemotherapy with radiation

There are two types of cystectomy, radical cystectomy and partial cystectomy.

For partial cystectomy, the doctor removes only part of your bladder. For muscle invasive bladder cancer, partial cystectomy is less likely because the cancer may have grown too far into the bladder. A radical cystectomy is when your whole bladder is removed. Radical cystectomy is believed the best care for muscle invasive bladder cancer. Bladder removal with chemotherapy raises survival rates for muscle invasive bladder cancer patients.

In radical cystectomy your doctor will remove 4:

- The whole bladder

- Nearby lymph nodes

- Part of the urethra

- The prostate and the seminal vesicles (in men)

- The uterus, ovaries, fallopian tubes and part of the vagina (in women).

- Other nearby tissues may also be removed.

When the whole bladder is removed, the surgeon makes some other way for urine to be gathered from the kidneys and stored before you pass it out of your body. Ask your urologist about urinary diversion. Before removing your bladder, your doctor will likely offer neoadjuvant chemotherapy 5. Adjuvant means, “added to.” About 6-8 weeks after chemotherapy, you will have your bladder surgery. If you choose not to have chemotherapy before surgery, then you may need it after surgery based on the tumor stage. This is adjuvant chemotherapy. If you have poor kidney function, hearing loss, heart problems and some other health issues, your doctor may not suggest chemotherapy for you.

Chemotherapy with radiation

Radiation alone is not given for muscle invasive bladder cancer. It is often done along with chemotherapy. Before starting chemotherapy and radiation, your surgeon will resect (cut away) the tumor during a trans urethral resection of bladder tumor (TURBT). This is done to try to remove all of the cancer cells. If you get this treatment, you must followup with your doctor. You will need to have ongoing cystoscopy exams, imaging tests (e.g. CT scan) and other methods to check the tumor.

Radical cystectomy risks and possible complications

Radical cystectomy is a complex surgery, involving the manipulation of many internal organs in your abdomen. Because of this, cystectomy carries with it certain risks, including:

- Bleeding (may require a blood transfusion)

- Infection

- Blood clots

- Heart attack

- Infection

- Pneumonia or other lung problems

- Failure to remove all of the cancer, or cancer comes back

- Problems with the stoma

- Abnormal levels of vitamins or minerals in the blood, requiring lifelong medication

- Scarring and narrowing of the ureters

- Bowel obstruction

- Problems with sexual function or with fertility

- Risks of anesthesia. The anesthesiologist will discuss these with you.

- Rarely, death can happen after surgery.

Since radical cystectomy is a surgery not just to remove the bladder but also to create a urinary diversion, the surgery includes additional risks, such as:

- Dehydration

- Electrolyte abnormalities

- Urinary tract infection

- A blockage that keeps food or liquid from passing through your intestines (bowel obstruction)

- A blockage in one of the tubes that carries urine from the kidneys (ureter blockage)

Some complications may be life-threatening. You may need to go back to the operating room for surgery to fix the complication, or you may need to be readmitted to the hospital. Ask your surgeon what additional risks there may be for your particular surgery.

Radical cystectomy with ileal conduit

During a radical cystectomy, the bladder is removed along nearby lymph nodes and organs that the cancer may spread to are also removed. These may include some reproductive organs, such as the prostate and seminal vesicles. Removal of these organs can lead to problems with sexual function, including the ability to get or keep an erection. It can also cause infertility. Your doctor can tell you more about this and your options.

After your doctor removes your bladder, he or she makes a new way for you to pass urine. This is called an ileal conduit. It’s made from a piece of your small intestine called the ileum. One end connects to your ureters. These are the tubes that carry urine from the kidneys to the bladder. The other end connects to an opening the doctor makes in the skin of your lower belly. This is called a urostomy, or a stoma.

After the surgery, urine will pass out of your body through the stoma and into a plastic bag worn outside your body. You’ll need to wear a bag all of the time. And you’ll need to empty and change the bag regularly. You’ll also need to take care of your stoma and the skin around it. You’ll be taught how to do this while you’re in the hospital.

Most people go home 1 to 2 weeks after the surgery. To fully recover, you will probably need 6 to 8 weeks.

Surgery to remove your bladder will not affect your sexual or reproductive life. But if a woman also has her uterus and ovaries removed, she will not be able to get pregnant. She could also start menopause and have hot flashes or other symptoms of menopause. And if a man has his prostate gland and seminal vesicles removed, he may have problems getting an erection. He will also not be able to get a woman pregnant. If you are a man who may want to father a child in the future, talk to your doctor. There are ways to save your sperm before the surgery.

Radical cystectomy recovery

After surgery, your belly will be sore, and you will probably need pain medicine for 1 to 2 weeks. You can expect your urostomy (stoma) to be swollen and tender at first. This usually improves after 2 to 3 weeks. You may notice some blood in your urine or that your urine is light pink for the first 3 weeks after surgery. This is normal.

While you are recovering from surgery, you will also be learning to care for your stoma. You may find it helpful to meet several times with a nurse who can teach you how to care for your stoma and use a urostomy pouch or bag.

Many people can return to work or their usual activities 4 to 6 weeks after surgery. But you will probably need 6 to 8 weeks to fully recover from the surgery.

Bladder cancer surgery may affect sexual function. If a woman’s uterus and ovaries are removed during the surgery, she will not be able to get pregnant, and menopause may start. She may have hot flashes and other symptoms of menopause. And if a man’s prostate gland and seminal vesicles are removed, he may have problems getting an erection and will not be able to make a woman pregnant.

Cystectomy has the potential for a big impact on quality of life, but even so, you can still lead a pretty normal life after cystectomy surgery.

You may have concerns about having a stoma, if you have that type of surgery. Work with your medical care team to understand what to expect with a stoma and how to address some of your concerns. With time, you can feel more at ease with caring for your stoma. As you gain confidence, you can enjoy the people and social activities you always enjoyed.

With neobladder reconstruction, your new bladder starts out small and slowly gets bigger over the first few months. At first, you may need to urinate every few hours during the day, or as often as your doctor recommends. As time goes on, you may be able to increase the time between urination to every four hours. It’s important to follow the schedule your doctor recommends so that the new bladder doesn’t stretch to become too big, as this may make it difficult to empty your bladder completely.

You may also feel sad or depressed, or you may worry about how your body will look after surgery. You may worry about whether the surgery will affect your ability to have sex. These concerns are common. Ask your doctor about support groups or other resources that can help you with this.

After the radical cystectomy procedure

You may need to stay in the hospital for up to five or six days after surgery. This time is required so that your body can recover from the surgery. The intestines tend to be the last part to wake up after surgery, so you may need to be in the hospital until your intestines are ready once again to absorb fluids and nutrients.

After general anesthesia, you may experience side effects such as sort throat, shivering, sleepiness, dry mouth, nausea and vomiting. These may last for a few days but should get better.

Starting the morning after surgery, your health care team may have you get up and walk often. Walking promotes healing and the return of bowel function, improves your circulation, and helps prevent joint stiffness and blood clots.

You may have some pain or discomfort around your incision or incisions for a few weeks after surgery. As you recover, your pain should gradually get better. Before you leave the hospital, talk with your doctor about medicine and other ways to improve your comfort.

Urinary changes

If you have urinary conduit surgery, you may have drainage of fluid from your urethra for six to eight weeks after surgery. Usually, the drainage slowly changes in color from bright red to pink, brown and then yellow.

With neobladder reconstruction, you may have bloody urine after surgery. In a few weeks, your urine should return to a yellowish color.

With either procedure, you can expect to see mucus in your urine, because the piece of intestine used in the procedure will still make mucus like your intestines normally do. Over time, you should have less mucus in your urine, but it will never go away completely. If you have a neobladder, you may need to flush your catheter if you have significant mucus to prevent plugging.

Sexual changes

After cystectomy, you may experience sexual changes. Share your concerns with your partner and be patient as you both learn to live with a new normal.

For men, nerve damage during surgery could impact ability to have erections. This can improve over time, but you may want to discuss this possibility with your doctor and ask whether your doctor can use nerve-sparing techniques during surgery. But even with nerve-sparing techniques, it might take some time for erectile function to return. Many options exist to help with erectile function after cystectomy. Be patient and work with your doctor if this is an important part of your recovery.

For women, changes to the vagina could make sex less comfortable after surgery. Nerve damage also can impact arousal and ability to have an orgasm. Ask your doctor whether nerve-sparing surgery might be an option for you. If you do experience sexual difficulties after surgery, take your time, be patient and discuss your concerns with your doctor if this is an important part of your recovery.

Intimacy with a stoma pouch is still possible. Know that intimacy won’t hurt your stoma, and reassure your partner that sex is OK. To minimize possible leaks, empty the pouch before sex. A pouch cover, sash or snug-fitting top can secure the pouch and keep it out of your way. You may need to experiment with different positions during intercourse until you find what’s comfortable for you.

How to care for yourself at home

Medicines

- Your doctor will tell you if and when you can restart your medicines. He or she will also give you instructions about taking any new medicines.

- If you take blood thinners, such as warfarin (Coumadin), clopidogrel (Plavix), or aspirin, be sure to talk to your doctor. He or she will tell you if and when to start taking those medicines again. Make sure that you understand exactly what your doctor wants you to do.

- Take pain medicines exactly as directed.

- If your doctor gave you a prescription medicine for pain, take it as prescribed.

- If you are not taking a prescription pain medicine, ask your doctor if you can take an over-the-counter medicine.

- Do not take more than two pain medicines at the same time unless your doctor told you to. Many pain medicines contain Tylenol, which is also called acetaminophen. If you take too much acetaminophen, you can become very sick.

- If you think your pain medicine is making you sick to your stomach:

- Take your medicine after meals (unless your doctor has told you not to).

- Ask your doctor for a different pain medicine.

- If your doctor prescribed antibiotics, take them as directed. Do not stop taking them just because you feel better. You need to take the full course of antibiotics.

Incision care

- If you have strips of tape on the cut (incision) the doctor made, leave the tape on for a week or until it falls off.

- Wash the area daily with warm, soapy water, and pat it dry. Don’t use hydrogen peroxide or alcohol, which can slow healing. You may cover the area with a gauze bandage if it weeps or rubs against clothing. Change the bandage every day.

- Keep the area clean and dry.

Activity

- Rest when you feel tired. Getting enough sleep will help you recover.

- Try to walk each day. Start by walking a little more than you did the day before. Bit by bit, increase the amount you walk. Walking boosts blood flow and helps prevent pneumonia and constipation.

- Avoid strenuous activities, such as bicycle riding, jogging, weight lifting, or aerobic exercise, until your doctor says it is okay.

- Avoid lifting more than 2.5 kilograms for about 4 weeks or until your doctor says it is okay. This may include a child, grocery bags and milk containers, a heavy briefcase or backpack, cat litter or dog food bags, or a vacuum cleaner.

- Ask your doctor when you can drive again.

- You will probably be able to go back to work or your normal routine in 4 to 6 weeks. This depends on the type of work you do and if you have any further treatment.

- You may take a bath or shower as usual. You can bathe with the pouch on or off. Gently pat the skin around your stoma dry after bathing.

Diet

- You can eat your normal diet. If your stomach is upset, try bland, low-fat foods like plain rice, broiled chicken, toast, and yogurt.

- Drink plenty of fluids to avoid becoming dehydrated.

Other instructions

- You may notice that your bowel movements are not regular right after your surgery. This is common. Try to avoid constipation and straining with bowel movements. You may want to take a fiber supplement every day. If you have not had a bowel movement after a couple of days, ask your doctor about taking a mild laxative.

- Follow your doctor’s or nurse’s instructions for caring for your stoma.

- To control pain when you cough or sneeze, hold a pillow over your incision.

Call your local emergency number anytime you think you may need emergency care. For example, call if:

- You passed out (lost consciousness).

- You have chest pain, are short of breath, or cough up blood.

See your doctor now or seek immediate medical care if:

- You have pain that does not get better after you take pain medicine.

- You have nausea or vomiting that doesn’t go away.

- You have loose stitches, or your incision comes open.

- Unusual pain, redness, swelling, bleeding, or drainage from the incision site.

- Pain, redness, swelling, odor, or drainage at the stoma site.

- You have signs of infection, such as:

- Increased pain, swelling, warmth, or redness.

- Red streaks leading from the area.

- Pus draining from the area.

- A fever of 100.4°F (38°C)

- You are not passing urine into your urostomy pouch for longer than 4 hours.

- You are passing bloody urine with clots.

- You have symptoms of a urinary tract infection. These may include:

- Pain in the flank, which is just below the rib cage and above the waist on either side of the back.

- Blood in your urine, beyond the light pink color expected in the first 3 weeks.

- A fever.

- You are sick to your stomach or cannot drink fluids.

- You have signs of a blood clot in your leg (called a deep vein thrombosis), such as:

- Pain in your calf, back of the knee, thigh, or groin.

- Redness or swelling in your leg.

Watch closely for changes in your health, and be sure to contact your doctor if you have any problems.

- National Collaborating Centre for Cancer (UK). Bladder Cancer: Diagnosis and Management. London: National Institute for Health and Care Excellence (UK); 2015 Feb. (NICE Guideline, No. 2.) 5, Managing muscle-invasive bladder cancer. Available from: https://www.ncbi.nlm.nih.gov/books/NBK356289

- Williams SB, Shan Y, Jazzar U, et al. Comparing Survival Outcomes and Costs Associated With Radical Cystectomy and Trimodal Therapy for Older Adults With Muscle-Invasive Bladder Cancer. JAMA Surg. 2018;153(10):881–889. doi:10.1001/jamasurg.2018.1680 https://www.ncbi.nlm.nih.gov/pmc/articles/PMC6584312

- Williams SB, Huo J, Kosarek CD, et al. Population-based assessment of racial/ethnic differences in utilization of radical cystectomy for patients diagnosed with bladder cancer. Cancer Causes Control. 2017;28(7):755–766. doi:10.1007/s10552-017-0902-2 https://www.ncbi.nlm.nih.gov/pmc/articles/PMC5497706

- Bladder Cancer Treatment (PDQ®)–Patient Version. https://www.cancer.gov/types/bladder/patient/bladder-treatment-pdq

- Chang SS, Bochner BH, Chou R, et al. Treatment of Non-Metastatic Muscle-Invasive Bladder Cancer: AUA/ASCO/ASTRO/SUO Guideline [published correction appears in J Urol. 2017 Nov;198(5):1175]. J Urol. 2017;198(3):552–559. doi:10.1016/j.juro.2017.04.086 https://www.ncbi.nlm.nih.gov/pmc/articles/PMC5626446