Rectovaginal fistula

Rectovaginal fistula is an epithelial-lined tract between the rectum and vagina 1. Characteristics of rectovaginal fistula, for example, site, size, length, activity, and symptoms, vary depending on the cause of the fistula, patient factors, and the treatment received 2. Rectovaginal fistula is a potentially challenging surgical condition for both the patient and health care team. The underlying cause determines the method of assessment, management, and prognosis. Today, most rectovaginal fistulas can be surgically corrected via a number of approaches 3. However, a small percentage of rectovaginal fistula cannot be corrected, because of patient comorbidity or disease-related factors; in these cases, patients can be helped only by fecal diversion 4.

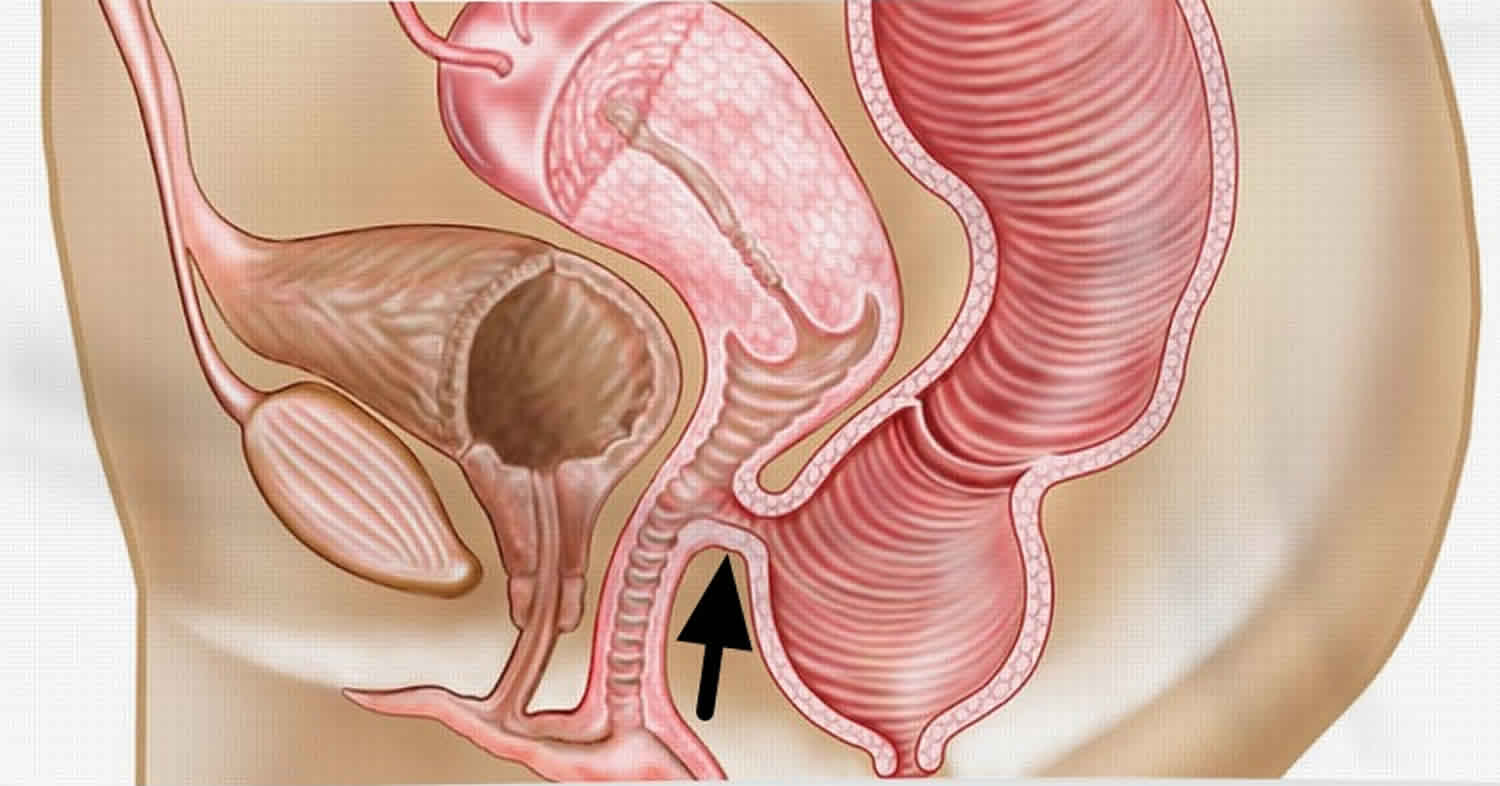

Rectovaginal fistulas are divided into 2 groups by location:

- Low rectovaginal fistulas are located in the lower third of the rectum and the lower half of the vagina. They are closest to the anus and are repaired with a perineal surgical approach.

- High rectovaginal fistulas are located between the middle third of the rectum and the posterior vaginal fornix. They require a transabdominal surgical repair approach.

- Most rectovaginal fistulas are less than 2 cm in diameter and are stratified by size:

- Small: Less than 0.5 cm in diameter

- Medium-sized: 0.5 to 2.5 cm in diameter

- Large rectovaginal fistulas: Exceed 2.5 cm in diameter

Rectovaginal fistula causes

Rectovaginal fistula formation results as a complication of an underlying disease, injury or surgical event 5. Diseases of the vagina or the pelvic organs can be complicated with a persistent connection between the rectum and vagina. The common causes of rectovaginal fistula are 6:

- Obstetric-related injury: This is the most common cause of traumatic rectovaginal fistula, and probably for all rectovaginal fistulas 7. This includes third- and fourth-degree lacerations during vaginal delivery.

- Surgical procedure: Surgical interventions that cause unrecognized vaginal or rectal injury, insufficient tissue thickness between the two organs, or ischemia of the tissue may result in perforation and fistula formation through the damaged tissue.

- Diverticular disease: Complex diverticular disease is a common cause of fistula connecting to an intra-abdominal organ like the bladder and vagina 8. Erosion of the diverticular wall with inflammation and abscess can extend, involve, and erode the adjacent organ walls resulting in a fistulous connection. An occasional increase in the luminal pressure on either side of the fistula and the continued inflammatory process will maintain the fistula patent.

- Crohn’s disease: Chronic inflammatory bowel diseases, especially Crohn’s disease, is a well-known cause of intestinal fistulization 9. Crohn’s disease is a transmural disease that involves the entire thickness of the bowl making an extension to and involvement of adjacent tissues and organs very common 10.

- Malignancy: Cancer of intestine or adjacent organs is a known cause of bowel perforation and fistulization. rectovaginal fistula can result from vaginal, cervical or more commonly rectal cancer that involves the entire wall thickness and extends to the adjacent vagina. These fistulae are also called malignant fistulae.

- Radiation: Radiation causes long-term chronic tissue inflammation with poor healing and repair processes. Therefore, fistulae caused by radiation manifest after a lag period from the radiation exposure 11.

- Non-surgical injuries and foreign bodies: Injuries in trauma or by a foreign body can result in a non-healing abnormal connection with the vagina.

There are a number of causes that are abbreviated in the mnemonic “FRIEND” (Foreign body, Radiation, Inflammation, Epithelization, Neoplasm, Distal obstruction). These are known causes of non-healing in fistulous diseases. They should not be mixed with the primary or underlying causes of rectovaginal fistula formation.

Rectovaginal fistula symptoms

The clinical presentation of rectovaginal fistula varies little. A few patients are asymptomatic, but most report the passage of flatus or stool through the vagina, which is understandably distressing. Patients may also experience vaginitis or cystitis. At times, a foul-smelling vaginal discharge develops, but frank stool through the vagina usually occurs only when the patient has diarrhea. The clinical picture may include fecal incontinence due to associated anal sphincter damage or bloody, mucus-rich diarrhea caused by the underlying clinical cause.

A detailed history of the underlying disease should be explored. Clinically, the escape of stool or gas from the rectum to the vagina through the fistula gives the abnormal signs and symptoms of foul-smell vaginal discharge, dyspareunia, passing air, bleeding, and passage of frank stool especially when the patient has diarrhea. Further symptoms of complications like symptoms of cystitis or vaginitis are occasionally encountered. Symptoms of an underlying disease like rectal obstructing cancer or diverticulosis may be present.

Physical exam of the vagina, the source of the symptoms, will likely reveal irritation, erythema, swelling, discharge, stool and possible fistula opening in speculum exam. Office colposcopic exam may reveal more details of the vaginal epithelium and the fistula site as an indurated indentation. A rectovaginal examination may reveal signs of the underlying disease like an obstructing low rectal tumor or phlegmon, Crohn’s disease, or tissue atrophy from radiation.

Rectovaginal fistula diagnosis

Physical examination is essential. This usually confirms the diagnosis of rectovaginal fistula and provides a great deal of information regarding the size and location of the fistula, the functioning of the sphincters, and the possibility of inflammatory bowel disease or local neoplasm. Anal sphincter disruptions are commonly seen in association with rectovaginal fistulas of obstetric origin. Sphincter function should be evaluated prior to any repair.

Office examination usually consists of a rectovaginal examination (visual and palpation) and proctosigmoidoscopy. The fistula opening may be seen as a small dimple or pit and occasionally can be gently probed for confirmation.

The suspicion of Crohn disease should be high if there is any other abnormality of the rectal mucosa or a previous or currently coexisting fistula-in-ano. Failure to recognize Crohn disease can lead to inappropriate operative intervention and can worsen the patient’s situation.

Placing a vaginal tampon, instilling methylene blue into the rectum, and examining the tampon after 15-20 minutes can often establish the presence of rectovaginal fistula. If the tampon is unstained, another part of the gastrointestinal (GI) tract may be involved.

Laboratory studies (eg, complete blood count [CBC], blood cultures, electrolytes, blood urea nitrogen [BUN], creatinine, and type and screen) are obtained to assess for sepsis, which is extremely rare in fistulas between the gastrointestinal (GI) tract and the female genital tract. Laboratory studies are also helpful in the establishment of preoperative baselines.

Endoscopy

Flexible endoscopy (sigmoidoscopy or colonoscopy) is used to fully evaluate the possibility of inflammatory bowel disease (IBD). Because treatment varies according to the diagnosis, endoscopy with biopsies must precede any operative approach to the fistula when inflammatory bowel disease is in the differential diagnosis.

Imaging studies

Ancillary studies may illustrate a rectovaginal fistula that is elusive on physical examination 12. Barium enema can demonstrate rectovaginal fistula or the more common sigmoid-vaginal cuff fistula observed in diverticulitis. Computed tomography (CT) often shows perifistular inflammation, identifying the responsible digestive organ. Endorectal and transvaginal ultrasonography may be used to help identify low fistulas. Magnetic resonance imaging has been employed in the diagnosis of rectovaginal fistulas 13.

Rectovaginal fistula treatment

Treating rectovaginal fistula involves treating the underlying disease, the fistula itself and any related complications 14. Therefore, confirming the rectovaginal fistula cause should be done before planning treatment. Treatment approach depends on many factors like condition severity, acuity, presenting symptoms, patient’s general condition, underlying cause and complications resulting from the rectovaginal fistula 15. Because the symptoms of rectovaginal fistula are so distressing, surgical therapy is almost always indicated. Exceptions include patients who are moribund and those for whom the proposed anesthesia and surgery pose prohibitive risks. Note that surgical therapy means repair in most cases. Some patients, however, are better served by a diverting stoma than by an ill-advised repair attempt.

Treatment of Crohn’s disease, diverticular disease or colorectal or gynecologic cancers should follow the principles of treating these diseases primarily. Treating rectovaginal fistula depends to a great extent on treating the underlying primary disease.

In 2016, the American Society of Colon and Rectal Surgeons published the following guidelines on the management of rectovaginal fistula 16:

- Nonoperative management is recommended for initial management of obstetrical rectovaginal fistula; it may also be considered for other benign and minimally symptomatic fistulas

- A draining seton may be needed to facilitate resolution of acute inflammation or infection associated with an rectovaginal fistula

- An endorectal advancement flap, with or without sphincteroplasty, is the procedure of choice for most simple rectovaginal fistulas

- An episioproctotomy may be performed to repair obstetrical or cryptoglandular rectovaginal fistulas associated with extensive anal sphincter damage

- A gracilis muscle or bulbocavernosus muscle (Martius) flap is recommended for a recurrent or otherwise complex rectovaginal fistula

- A high rectovaginal fistula resulting from complications of a colorectal anastomosis often requires an abdominal approach for repair

- Proctectomy with colon pullthrough or coloanal anastomosis may be necessary to repair a radiation-related or recurrent complex rectovaginal fistula.

Medical therapy

Conservative or non-surgical treatment approach of the symptoms and possible complications like urinary tract infection (UTI), local irritation, and site infection can be used in selected patients. This approach can be considered in high-risk patients and severe underlying disease. Use local care, drainage of abscesses, and directed antibiotic therapy to treat acute rectovaginal fistulas of traumatic origin including those caused by obstetric 17 and operative trauma, rectovaginal fistulas complicated by secondary infection, and fistulas of infectious origin. Allow tissues to heal for 6-12 weeks. Dietary modification and supplemental fiber can greatly diminish symptoms during this period.

Many rectovaginal fistulas resulting from obstetric or operative trauma heal completely, requiring no further therapy. When the fistula persists after this period of treatment and the tissues become uninflamed and supple, repair may be considered.

Perform a biopsy on any area suggestive of neoplasm. Treat neoplasms as appropriate. In this setting, highly symptomatic fistulas may prompt the physician and patient to consider a diverting colostomy for patient comfort. Otherwise, fecal diversion is rarely used with rectovaginal fistulas 4.

If the evaluation is consistent with the diagnosis of inflammatory bowel disease (IBD), institute appropriate medical therapy. Repair of an rectovaginal fistula can be performed while the patient is on steroid therapy, with the understanding that the risk of failure is increased. Even after initial failed repair attempts, some patients with Crohn disease can maintain rectovaginal fistula repair while on antimetabolites, such as 6-mercaptopurine or azathioprine. Clinical use of infliximab 18 suggests that few fistulas heal completely, but most patients experience dramatic improvements in their symptoms.

Predictors of failure necessitating fecal diversion have been identified and include significant colonic involvement and the presence of anal stricture 4. The development of carcinoma has been described in Crohn fistulas 19.

Rectovaginal fistulas originating from radiation therapy are very difficult to treat surgically 20 and medical therapy is often initially recommended in this setting. Diet and fiber are the mainstays of treatment.

Rectovaginal fistula surgery

Surgical treatment is almost always indicated. Typically, such treatment consists of repair via either a local or a transabdominal approach.

Minimally invasive approaches have been described 21. Mukwege et al 22 applied a laparoscopic approach to the treatment of high rectovaginal fistulas in 10 patients and reported a clinical success rate of 90% (median follow-up, 14.3 months). Lamazza et al 23 used endoscopic placement of a self-expanding metal stent to treat 10 patients with rectovaginal fistula after colorectal resection for cancer. At follow-up (mean, 24 months), eight rectovaginal fistulas had healed without major fecal incontinence; the other two had been reduced sufficiently to allow a flap transposition.

Preparation for surgery

Complete mechanical bowel preparation is essential for transabdominal repair of rectovaginal fistula and is also recommended for local repair. The practice of including poorly absorbed oral antibiotics in the bowel preparation is under scrutiny. Data suggest that administering intravenous (IV) antibiotics in such a way as to ensure appropriate tissue levels at the start of the procedure is sufficient for prophylaxis. The author recommends that prophylactic IV antibiotics be given preoperatively to all patients undergoing rectovaginal fistula repairs, whether transabdominal or local.

Although diverting colostomy was used in the past, the overwhelming majority of rectovaginal fistulas are now repaired without this procedure being performed beforehand.

Cleanse the vaginal lumen with an antiseptic solution, such as povidone-iodine. Insert a catheter into the urinary bladder.

If a transabdominal procedure is planned, perform standard preoperative cardiopulmonary evaluation as appropriate. Prophylaxis against venous thromboembolism is essential and may include the use of fractionated or unfractionated heparin, as well as the employment of sequential compression devices. If the pelvis has been irradiated or previously operated on, the use of ureteral catheters may aid in dissection.

Bricker patch

The onlay Bricker patch also has been used to repair rectovaginal fistulas, chiefly those produced by radiation. Briefly, the rectosigmoid colon is mobilized transabdominally, and the rectovaginal fistula is exposed. The rectosigmoid is divided above the fistula. The proximal end is brought out as an end sigmoid colostomy. The distal rectosigmoid is turned down, and the open end is anastomosed to the debrided edge of the rectal opening of the fistula, essentially creating an internal loop with drainage through the anus.

When healing of the inferior-patched rectum can be demonstrated radiologically several months later, continuity of the colon is reestablished by anastomosis of the colostomy to the apex of the patch loop in an end-to-side fashion.

An advantage to this procedure is that it is less difficult than resection and therefore may be less likely to cause hemorrhage or organ injury. A disadvantage is that the radiation-damaged rectum is left in place and in use, with the possibility of further morbidity, including bleeding and stricture.

Although situations exist where this approach may be preferable to a resection approach, the author believes that resection of the radiation-damaged bowel provides the best long-term results in patients who are reasonable operative candidates.

Management of rectovaginal fistula associated with Crohn disease

Rectovaginal fistulas associated with Crohn disease are difficult to manage 24. When symptoms are few, operative intervention may not be indicated. Conversely, severely symptomatic patients may require proctectomy.

Patients with relatively normal rectal mucosa and an rectovaginal fistula are good candidates for an endorectal advancement flap. In this specific setting, outcome is good, though not as good as in patients without Crohn disease. An endorectal advancement flap is considered the preferred technique for local rectovaginal fistula repair in patients with Crohn disease and a relatively normal rectum.

A multivariable logistic regression model identified immunomodulators as being associated with successful healing and smoking and steroid usage as being associated with failure 25.

Rectovaginal fistula repair

Local repair

Transanal advancement flap repair

The best results have been reported with transanal advancement flap repair 26. General, regional, or local anesthesia may be used. The patient is placed in the prone, flexed position with a hip roll in place; the buttocks are taped apart for exposure.

The fistula is identified using the operating anoscope. A flap is outlined, extending at least 4 cm cephalad to the fistula, with the base of the flap twice the width of the apex to allow adequate blood supply to the flap tip. Local anesthetic with epinephrine is injected submucosally to facilitate raising the flap and to diminish bleeding.

The flap, consisting of mucosa and submucosa, is raised; some surgeons include circular muscle as well. Meticulous hemostasis is imperative. The fistula tract is curetted gently. Circular muscle is closed over the fistula. The tip of the flap, which includes the fistula opening, is excised. The flap is sutured in place with simple interrupted absorbable sutures, effectively closing the rectal opening of the fistula. The vaginal side of the fistula is left open for drainage.

This approach separates the suture line from the fistula site and interposes healthy muscle between the rectal and vaginal walls. Proponents point out that the relatively high pressure within the rectum serves to buttress the repair, in contrast to a transvaginal repair, in which the intrarectal pressure is more prone to disrupt the repair. If indicated, sphincteroplasty can be performed concomitantly 27.

Transvaginal inversion repair

The vaginal mucosa is circumferentially elevated, exposing the fistula. Two or three concentric purse-string sutures are used to invert the fistula into the rectal lumen. The vaginal mucosa is reapproximated. This approach has generally been considered suitable only for small, low fistulas in otherwise healthy tissues with an intact perineal body. It is rarely performed today.

Bioprosthetic repair

A bioprosthetic interposition graft is placed by making a transverse incision over the midportion of the perineal body with dissection through the subcutaneous tissue. The fistula tract is transected. The dissection is continued 2 cm proximal to the transected fistula tract and laterally. The fistula openings are closed with 3-0 interrupted absorbable sutures.

The graft requires an overlap of 2 cm on all sides of the rectal and vaginal mucosal closures. A bioprosthetic plug is placed through the rectal opening and out the vaginal opening. The excess plug is trimmed and secured on the rectal side with 2-0 absorbable suture.

Conversion to complete perineal laceration with layer closure

In a conversion to complete perineal laceration with layer closure 4, the fistulous tract is laid open in the midline, essentially creating a cloaca. Closure in layers follows, identical to the classic obstetric repair of a fourth-degree perineal laceration. This method is described in the gynecologic literature; it is rarely employed by colorectal surgeons, because of concerns about juxtaposed suture lines.

Simple fistulotomy

Simple fistulotomy works well for true anovaginal fistulas, in which no sphincter is involved in the tract. If the technique is used to treat an rectovaginal fistula, however, partial or total fecal incontinence results.

Transabdominal repair

Transabdominal approaches are generally used for high rectovaginal fistulas when the fistula originates from a neoplasm, from radiation, or, occasionally, from IBD. They are also used if concomitant disease (eg, diverticulitis) warrants an abdominal approach. With approximation of healthy tissue in the absence of inflammation, infection, or tension, transabdominal repairs yield good long-term results. It is essential always to consider the morbidities of major abdominal surgery and any comorbid conditions related to the patient’s history.

Patients with fistulas due to radiation may have added morbidities associated with other irradiated tissues, such as the following:

- Cystitis

- Ureteral complications, including stricture and obstruction

- Vascular injury, including stenosis and occlusion

- Small-bowel injury, including stricture, malabsorption, and obstruction

- Neurologic complications

- Bony complications, including necrosis and fractures

Fistula division and closure without bowel resection

This is the simplest abdominal approach. The rectovaginal septum is dissected, the fistula is divided, and the rectum and vagina are closed primarily without bowel resection. Interposition of healthy tissue, such as omentum, may be used to buttress the repair and separate the suture lines. Good results have been reported when the fistula is not large and the tissues available for closure are healthy.

Bowel resection

When tissues are abnormal because of irradiation, inflammation, or neoplasm, the repair is doomed to failure unless the abnormal tissues are resected. Preserve functional anal sphincters whenever possible by use of a low anterior resection, a coloanal anastomosis technique, or a pull-through; the last alternative has the poorest results with respect to continence.

Rarely, abdominoperineal resection may be necessary for symptom control in the setting of radiation damage or neoplasm. An alternative, particularly in cases of poor operative risks or with patients whose survival is limited, is simple fecal diversion with a loop ileostomy or colostomy.

Ancillary procedures

A host of supplementary procedures have been described to augment bowel resection in the difficult pelvis. These include local flaps, such as the bulbocavernosus flap, and a variety of muscle, fascial, and musculocutaneous flaps for repair of large pelvic defects. A variety of graft procedures also have been described 28. All of these procedures have the goal of interposing healthy tissue between vaginal and rectal repairs. They are well described in the plastic surgery literature.

Postoperative care

Local repair

Attention must be paid to the patient’s bowel habits. Constipation or diarrhea can disrupt a repair. The goal is a soft, formed, deformable stool. The patient is carefully counseled regarding diet, copious fluid intake, and the use of stool softeners. The use of bulking agents immediately after repair is at the discretion of the surgeon and is a matter of individual preference rather than of scientifically proven practice. The use of oral antibiotics also varies.

The author prefers that patients use an oral broad-spectrum antibiotic for 3-5 days postoperatively, take 1 tablespoon of mineral oil orally twice daily for 2 weeks postoperatively, and avoid bulking agents for 2 weeks postoperatively. Patients need to refrain from sexual activity or any physical activity more strenuous than a slow walk for 3 weeks.

Transabdominal repair

Postoperative care after transabdominal repair is identical to the care administered to all patients who have undergone major laparotomy with bowel resection and anastomosis. Postoperative gastric decompression is performed selectively, in the expectation that 15-20% of patients require cessation of oral intake or gastric decompression for symptomatic postoperative ileus. Most patients can be offered sips of clear liquids on postoperative day 1.

Early ambulation is beneficial in many ways. Continue perioperative prophylaxis for thromboembolic events until the patient is ambulating well.

Long-term monitoring

Patients are seen 2 weeks after discharge for evaluation of wounds and bowel habits. In the absence of recurrent fistula symptoms or other specific indications, no follow-up investigation, aside from physical examination, is required.

If specific signs and symptoms are present, they are investigated appropriately. For example, fever, diarrhea, and low abdominal pain indicating an abscess are evaluated by means of computed tomography (CT) of the abdomen and pelvis. In this setting, physical examination may be difficult because of patient discomfort.

Rectovaginal fistula repair complications

Local repair

Bleeding is rarely encountered postoperatively, probably because of careful intraoperative hemostasis. If bleeding occurs beneath the flap, fistula recurrence is common. Infection is a feared complication, because it almost invariably results in a failed repair. However, good data on the incidence of infection after local repair are few. Of course, repairs may fail in the absence of infection as well. Rarely, postoperative pain precipitates urinary retention.

Transabdominal repair

These may include the usual complications of any laparotomy with bowel resection, including fistula recurrence. The most common complications are bleeding and wound infection, each with an incidence of less than 2-5% in reasonable-risk candidates. Pelvic abscess occurs in 5-7% of patients. Data from the United States and Europe suggest that anastomotic leaks occur more often than is clinically recognized. However, because intervention is indicated only in clinically evident leaks, routine postoperative anastomotic evaluation is not warranted.

Rectovaginal fistula prognosis

Recurrence of an rectovaginal fistula indicates a poorer prognosis for future repair attempts 29. In a study by Schouten et al 30, rectal sleeve advancement had an overall healing rate of 75% for persistent rectovaginal fistulas. Recurrence is influenced by the etiology of the fistula and by its complexity. Fistulas of obstetric origin and fistulas that are considered simple (rather than complex) fare better after repeated repair attempts.

Byrnes et al 31, in a retrospective cohort study assessing the outcomes of primary surgical repair of rectovaginal fistula in relation to fistula etiology and specific surgical approach, found that the surgical approach affected recurrence-free survival at 1 year, with a rate of 35.2% forr the local approach, 55.6% for the transvaginal or endorectal approach, 95% for the abdominal approach, and 33.3% for diversion only 31. Fistula cause did not significantly affect recurrence-free survival.

References- Tuma F, Al-Wahab Z. Rectovaginal Fistula. Treasure Island, FL: StatPearls; 2018.

- Tuma F, Waheed A, Al-Wahab Z. Rectovaginal Fistula. [Updated 2019 Jun 12]. In: StatPearls [Internet]. Treasure Island (FL): StatPearls Publishing; 2019 Jan-. Available from: https://www.ncbi.nlm.nih.gov/books/NBK535350

- Abu Gazala M, Wexner SD. Management of rectovaginal fistulas and patient outcome. Expert Rev Gastroenterol Hepatol. 2017 May. 11 (5):461-471.

- Galandiuk S, Kimberling J, Al-Mishlab TG, Stromberg AJ. Perianal Crohn disease: predictors of need for permanent diversion. Ann Surg. 2005 May. 241 (5):796-801; discussion 801-2.

- Thubert T, Cardaillac C, Fritel X, Winer N, Dochez V. [Definition, epidemiology and risk factors of obstetric anal sphincter injuries: CNGOF Perineal Prevention and Protection in Obstetrics Guidelines]. Gynecol Obstet Fertil Senol. 2018 Dec;46(12):913-921.

- Bhama AR, Schlussel AT. Evaluation and Management of Rectovaginal Fistulas. Dis. Colon Rectum. 2018 Jan;61(1):21-24.

- Mocumbi S, Hanson C, Högberg U, Boene H, von Dadelszen P, Bergström A, Munguambe K, Sevene E., CLIP working group. Obstetric fistulae in southern Mozambique: incidence, obstetric characteristics and treatment. Reprod Health. 2017 Nov 10;14(1):147.

- Bahadursingh AM, Longo WE. Colovaginal fistulas. Etiology and management. J Reprod Med. 2003 Jul;48(7):489-95.

- Sheedy SP, Bruining DH, Dozois EJ, Faubion WA, Fletcher JG. MR Imaging of Perianal Crohn Disease. Radiology. 2017 Mar;282(3):628-645.

- Cohen JL, Stricker JW, Schoetz DJ Jr, Coller JA, Veidenheimer MC. Rectovaginal fistula in Crohn’s disease. Dis Colon Rectum. 1989 Oct. 32 (10):825-8.

- Iwamuro M, Hasegawa K, Hanayama Y, Kataoka H, Tanaka T, Kondo Y, Otsuka F. Enterovaginal and colovesical fistulas as late complications of pelvic radiotherapy. J Gen Fam Med. 2018 Sep;19(5):166-169.

- Shobeiri SA, Quiroz L, Nihira M. Rectovaginal fistulography: a technique for the identification of recurrent elusive fistulas. Int Urogynecol J Pelvic Floor Dysfunct. 2009 May. 20 (5):571-3.

- VanBuren WM, Lightner AL, Kim ST, Sheedy SP, Woolever MC, Menias CO, et al. Imaging and Surgical Management of Anorectal Vaginal Fistulas. Radiographics. 2018 Sep-Oct. 38 (5):1385-1401.

- Karp NE, Kobernik EK, Berger MB, Low CM, Fenner DE. Do the Surgical Outcomes of Rectovaginal Fistula Repairs Differ for Obstetric and Nonobstetric Fistulas? A Retrospective Cohort Study. Female Pelvic Med Reconstr Surg. 2019 Jan/Feb;25(1):36-40.

- Abu Gazala M, Wexner SD. Management of rectovaginal fistulas and patient outcome. Expert Rev Gastroenterol Hepatol. 2017 May;11(5):461-471.

- [Guideline] Vogel JD, Johnson EK, Morris AM, Paquette IM, Saclarides TJ, Feingold DL, et al. Clinical Practice Guideline for the Management of Anorectal Abscess, Fistula-in-Ano, and Rectovaginal Fistula. Dis Colon Rectum. 2016 Dec. 59 (12):1117-1133.

- Browning A, Menber B. Women with obstetric fistula in Ethiopia: a 6-month follow up after surgical treatment. BJOG. 2008 Nov. 115 (12):1564-9.

- Nirei T, Kazama S, Hiyoshi M, Tsuno NH, Nishikawa T, Tanaka T, et al. Successful treatment of rectovaginal fistula complicating ulcerative colitis with infliximab: a case report and review of the literature. J Clin Med Res. 2015 Jan. 7 (1):59-61.

- Laurent S, Barbeaux A, Detroz B, Detry O, Louis E, Belaiche J, et al. Development of adenocarcinoma in chronic fistula in Crohn’s disease. Acta Gastroenterol Belg. 2005 Jan-Mar. 68 (1):98-100.

- Bricker EM, Johnston WD. Repair of postirradiation rectovaginal fistula and stricture. Surg Gynecol Obstet. 1979 Apr. 148 (4):499-506.

- Kumaran SS, Palanivelu C, Kavalakat AJ, Parthasarathi R, Neelayathatchi M. Laparoscopic repair of high rectovaginal fistula: is it technically feasible?. BMC Surg. 2005 Oct 12. 5:20.

- Mukwege D, Mukanire N, Himpens J, Cadière GB. Minimally invasive treatment of traumatic high rectovaginal fistulas. Surg Endosc. 2016 Jan. 30 (1):379-87.

- Lamazza A, Fiori E, Schillaci A, Sterpetti AV, Lezoche E. Treatment of rectovaginal fistula after colorectal resection with endoscopic stenting: long-term results. Colorectal Dis. 2015 Apr. 17 (4):356-60.

- Löffler T, Welsch T, Mühl S, Hinz U, Schmidt J, Kienle P. Long-term success rate after surgical treatment of anorectal and rectovaginal fistulas in Crohn’s disease. Int J Colorectal Dis. 2009 May. 24 (5):521-6.

- El-Gazzaz G, Hull T, Mignanelli E, Hammel J, Gurland B, Zutshi M. Analysis of function and predictors of failure in women undergoing repair of Crohn’s related rectovaginal fistula. J Gastrointest Surg. 2010 May. 14 (5):824-9.

- Casadesus D, Villasana L, Sanchez IM, Diaz H, Chavez M, Diaz A. Treatment of rectovaginal fistula: a 5-year review. Aust N Z J Obstet Gynaecol. 2006 Feb. 46 (1):49-51.

- Khanduja KS, Yamashita HJ, Wise WE Jr, Aguilar PS, Hartmann RF. Delayed repair of obstetric injuries of the anorectum and vagina. A stratified surgical approach. Dis Colon Rectum. 1994 Apr. 37 (4):344-9.

- Jasonni VM, La Marca A, Manenti A. Rectovaginal fistula repair using fascia graft of autologous abdominal muscles. Int J Gynaecol Obstet. 2006 Jan. 92 (1):85-6.

- Ulrich D, Roos J, Jakse G, Pallua N. Gracilis muscle interposition for the treatment of recto-urethral and rectovaginal fistulas: a retrospective analysis of 35 cases. J Plast Reconstr Aesthet Surg. 2009 Mar. 62 (3):352-6.

- Schouten WR, Oom DM. Rectal sleeve advancement for the treatment of persistent rectovaginal fistulas. Tech Coloproctol. 2009 Dec. 13 (4):289-94.

- Byrnes JN, Schmitt JJ, Faustich BM, Mara KC, Weaver AL, Chua HK, et al. Outcomes of Rectovaginal Fistula Repair. Female Pelvic Med Reconstr Surg. 2017 Mar/Apr. 23 (2):124-130.