Relapsing fever

Relapsing fever is bacterial infection caused by various spirochetes belonging to Borrelia species a Gram negative bacteria, characterized by recurring bouts of fever, chills, malaise, headache, muscle and joint aches and nausea 1. The causative organism and associated vector vary based on the geographic area of exposure 2. Borrelia species bacteria are visible with light microscopy and have the cork-screw shape typical of all spirochetes. Relapsing fever Borrelia spirochetes bacteria have a unique process of DNA rearrangement that allows them to periodically change the molecules on their outer surface. This process, called antigenic variation, allows the spirochete to evade the host immune system and cause relapsing episodes of fever and other symptoms. Three Borrelia species cause tick-borne relapsing fever in the United States: Borrelia hermsii, Borrelia parkerii, and Borrelia turicatae. The most common cause is cause is Borrelia hermsii.

There are two types of relapsing fever:

- Tick-borne relapsing fever: Tick-borne relapsing fever is transmitted by the ornithodoros tick. It occurs in Africa, Spain, Saudi Arabia, Asia, and certain areas in the western United States and Canada. The bacteria species associated with tick-borne relapsing fever are Borrelia duttoni, Borrelia hermsii, and Borrelia parkerii.

- Louse-borne relapsing fever (epidemic relapsing fever): Louse-borne relapsing fever is transmitted by body lice. It is most common in Asia, Africa, and Central and South America. The bacteria species associated with louse-borne relapsing fever is Borrelia recurrentis.

Tick-borne relapsing fever occurs in the western United States and is usually linked to sleeping in rustic, rodent-infested cabins in the mountains. In Texas, tick-borne relapsing fever is frequently linked to cave exposures. Louse-borne relapsing fever is transmitted by the human body louse and usually occurs in refugee settings in developing parts of the world.

Symptoms usually develop approximately 5-15 days after a bite from an infected soft tick and may include fever, headache, muscle pain (myalgia), and chills occasionally accompanied by nausea, joint pain (arthralgia), vomiting, or abdominal pain 3. Fever typically resolves after 3-5 days and the patient experiences up to a week of apparent

recovery before fever and other symptoms return. Up to a dozen relapses can occur as the Borrelia species bacteria repeatedly alters its surface antigens, each time eliciting a new immune response from its human host 4. Individuals who develop these or other symptoms after spending time in wilderness or following exposure to rodents or rodent nests should see a health care provider as soon as possible.

Louse-borne relapsing fever also known as epidemic relapsing fever, is mainly a disease of the developing world. It is currently seen in Ethiopia and Sudan. Famine, war, and the movement of refugee groups often results in louse-borne relapsing fever epidemics.

In both forms, the fever episode may end in “crisis.” This consists of shaking chills, followed by intense sweating, falling body temperature, and low blood pressure. This stage may result in death.

Relapsing fever should be suspected if someone coming from a high-risk area has repeated episodes of fever. This is largely true if the fever is followed by a “crisis” stage, and if the person may have been exposed to lice or soft-bodied ticks.

Tests that may be done include:

- Blood smear to determine the cause of the infection

- Blood antibody tests (sometimes used, but their usefulness is limited)

Antibiotics including penicillin and tetracycline are used to treat relapsing fever.

People with relapsing fever who have developed a coma, heart inflammation, liver problems, or pneumonia are more likely to die. With early treatment, the death rate is reduced.

Figure 1. Cases of tick-borne relapsing fever – United States, 1990 – 2011

Footnote: During the years 1990-2011, 483 cases of tick borne relapsing fever were reported in the western U.S., with infections being transmitted most frequently in California, Washington, and Colorado.

[Source 5 ]Relapsing fever causes

The term relapsing fever refers to a variety of recurrent fever syndromes caused by the spirochete, Borrelia.

Tick-borne relapsing fever

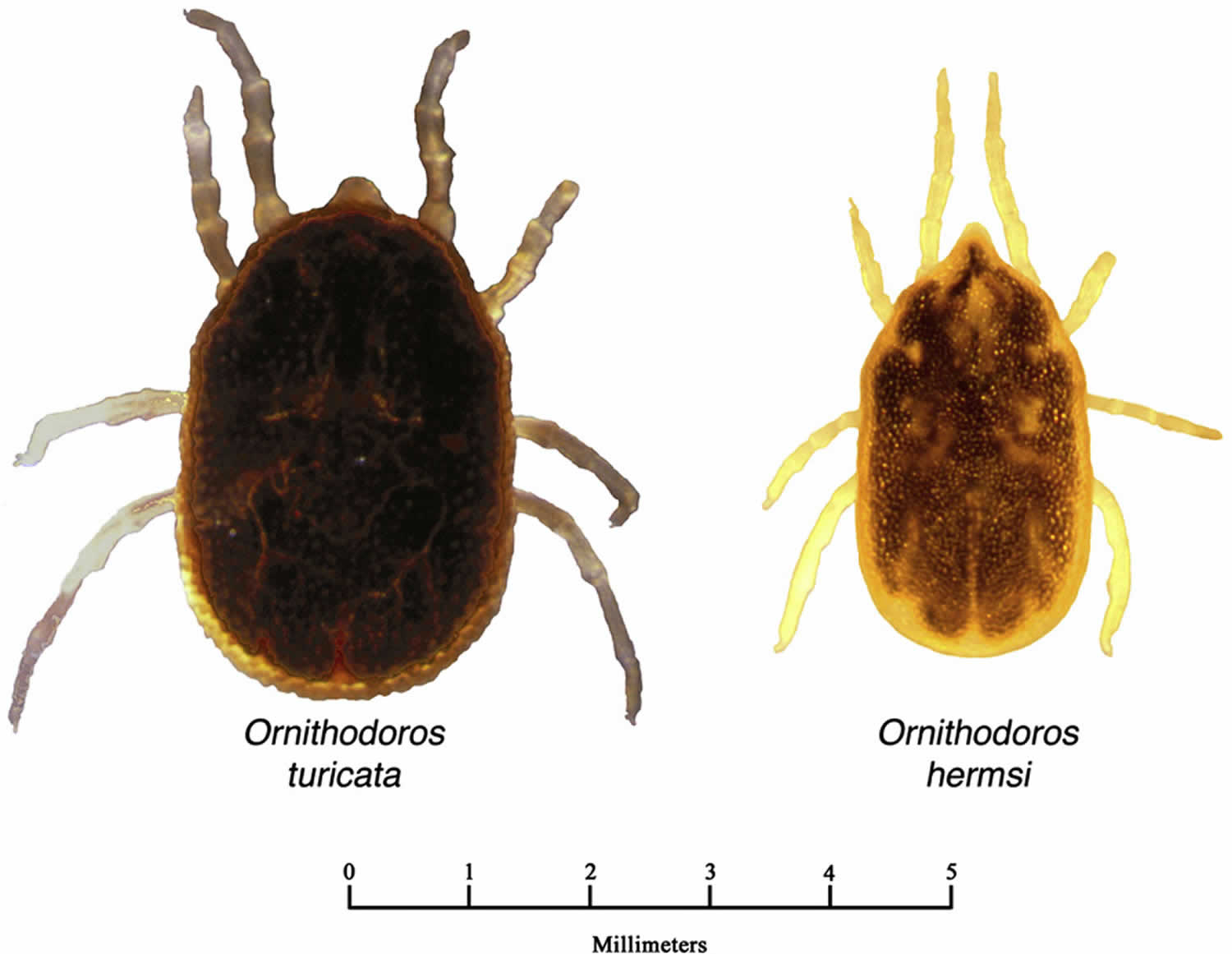

Tick-borne relapsing fever is an infection caused by Borrelia species bacteria and transmitted by soft ticks in North America. Soft ticks are known to inhabit the nests of small rodents and other mammals and birds and can remain in the nest for many years after the nest has been vacated 6. Tick-borne relapsing fever is transmitted via the bite of soft-bodied, night feeding Ornithodoros ticks. Bites from soft ticks are usually painless, at night and last less than 30 minutes. Therefore, a person may not realize that he or she was bitten 6. Tick-borne relapsing fever reported in the United States can be caused by several Borrelia species, including Borrelia hermsii, Borrelia turicatae, and Borrelia parkeri 7. Borrelia miyamotoi is a relapsing fever, similar to Lyme disease, transmitted by the Ixodes tick. It is reported in the northeastern United States, Japan, and Russia, with slight variations in presentation depending on geography 8.

- Borrelia hermsii – found in the soft tick Ornithodoros hermsi. This tick lives in close association with chipmunks, deer mice, wood rats, and some birds in western states, specifically in coniferous forests at elevations of 1200-8000 feet 9. A person typically becomes infected with Borrelia hermsii while sleeping in a rodent-infested cabin or other building. Borrelia hermsii is reported in the United States in Colorado, near Lake Tahoe, and near the Grand Canyon.

- Borrelia parkeri – found in the soft tick Ornithodoros parkeri, which inhabits burrows of ground squirrels and prairie dogs or caves in southwestern states at low elevations. Ornithodoros parkeri can also parasitize other mammalian hosts such as mice, cottontail rabbits, and burrowing owls 10.

- Borrelia turicatae – found in the soft tick Ornithodoros turicata, which is associated with ground squirrels, prairie dogs, wood rats, rabbits, and numerous other animals in the western United States 6. The ticks prefer areas with low humidity and low elevations and have been found in caves and underground burrows.

Tick-borne relapsing fever distribution

Tick-borne relapsing fever is found in discrete areas throughout the world, including mountainous areas of North America, plateau regions of Mexico, Central and South America, the Mediterranean, Central Asia, and much of Africa.

In the United States, tick-borne relapsing fever occurs most commonly in 14 western states: Arizona, California, Colorado, Idaho, Kansas, Montana, Nevada, New Mexico, Oklahoma, Oregon, Texas, Utah, Washington, and Wyoming (see Figure 1 above).

Tick-borne relapsing fever is spread by multiple tick species, each of which has a preferred habitat and set of hosts. Ornithodoros hermsi, the tick responsible for most cases in the United States, prefers coniferous forests at altitudes of 1500 to 8000 feet where it feeds on tree squirrels and chipmunks. The two other U.S. tick species that transmit tick-borne relapsing fever, Ornithodoros parkeri and Ornithodoros turicata, are generally found at lower altitudes in the Southwest, where they inhabit caves and the burrows of ground squirrels, prairie dogs, and burrowing owls.

Most tick-borne relapsing fever cases occur in the summer months when more people vacationing and sleeping in rodent-infested cabins. Nevertheless, tick-borne relapsing fever can also occur in the winter months. Fires started to warm a cabin are sufficient to activate ticks resting in the walls and woodwork.

Tick-borne relapsing fever transmission

Borrelia bacteria that cause tick-borne relapsing fever are transmitted to humans through the bite of infected “soft ticks” of the genus Ornithodoros. Soft ticks differ in two important ways from the more familiar “hard ticks” (e.g., the dog tick and the deer tick). First, the bite of soft ticks is brief, usually lasting less than half an hour. Second, soft ticks do not search for prey in tall grass or brush. Instead, they live within rodent burrows, feeding as needed on the rodent as it sleeps.

Humans typically come into contact with soft ticks when they sleep in rodent-infested cabins. The ticks emerge at night and feed briefly while the person is sleeping. The bites are painless, and most people are unaware that they have been bitten. Between meals, the ticks may return to the nesting materials in their host burrows.

There are several Borrelia species that cause tick-borne relapsing fever, and these are usually associated with specific species of ticks. For instance, Borrelia hermsii is transmitted by Ornithodoros hermsi ticks, Borrelia parkerii by Ornithodoros parkeri ticks, and Borrelia turicatae by Ornithodoros turicata ticks. Each tick species has a preferred habitat and preferred set of hosts:

- Ornithodoros hermsi tends to be found at higher altitudes (1500 to 8000 feet) where it is associated primarily with ground or tree squirrels and chipmunks.

- Ornithodoros parkeri occurs at lower altitudes, where they inhabit caves and the burrows of ground squirrels and prairie dogs, as well as those of burrowing owls.

- Ornithodoros turicata occurs in caves and ground squirrel or prairie dog burrows in the plains regions of the Southwest, feeding off these animals and occasionally burrowing owls or other burrow- or cave-dwelling animals.

Soft ticks can live up to 10 years; in certain parts of the Russia the same tick has been found to live almost 20 years. Individual ticks will take many blood meals during each stage of their life cycle, and some species can pass the infection along through their eggs to their offspring. The long life span of soft ticks means that once a cabin or homestead is infested, it may remain infested unless steps are taken to find and remove the rodent nest.

Louse borne relapsing fever (epidemic relapsing fever)

Borrelia recurrentis bacteria is the cause of epidemic relapsing fever or louse-borne relapsing fever, is reported most commonly in areas of crowding and poor personal hygiene, which is reported most frequently in northern and eastern Africa, particularly in regions affected by war and in refugee camps 1. Louse-borne relapsing fever is commonly found in Ethiopia, Sudan, Eritrea, and Somalia. Illness can be severe, with mortality of 30 to 70% in outbreaks. Louse-borne relapsing fever is caused by a spiral-shaped bacteria, Borrelia recurrentis, which is transmitted from human to human by the body louse.

Louse-borne relapsing fever epidemics occurred frequently in Europe during the early 20th Century. Between 1919 and 1923, 13 million cases resulting in 5 million deaths occurred in the social upheaval that overtook Russia and eastern Europe. During World War II, a million cases occurred in North Africa. Today, Louse-borne relapsing fever causes sporadic illness and outbreaks in sub-Saharan Africa and among migrants from Africa to Europe in recent years.

Other species causing relapsing fever in Africa include Borrelia duttonii, Borrelia hispanica, and Borrelia crocidurae. Humans are the only known host and reservoir of Borrelia recurrentis.

Relapsing fever prevention

Tick-borne relapsing fever prevention

- Avoid sleeping in rodent-infested buildings whenever possible. Although rodent nests may not be visible, other evidence of rodent activity (e.g., droppings) are a sign that a building may be infested.

- Prevent tick bites. Use insect repellent containing DEET (on skin or clothing) or permethrin (applied to clothing or equipment).

- If you are renting a cabin and notice a rodent infestation, contact the owner to alert them.

- If you own a cabin, consult a licensed pest control professional who can safely:

- Identify and remove any rodent nests from walls, attics, crawl spaces, and floors. (Other diseases can be transmitted by rodent droppings—leave this job to a professional!)

- Treat “cracks and crevices” in the walls with pesticide.

- Establish a pest control plan to keep rodents out.

Many cases of tick-borne relapsing fever have been linked to cabins with rodent infestation. In buildings where one or more cases of tick-borne relapsing fever have been identified, the building should be thoroughly inspected by a pest-control professional or other knowledgeable persons to locate and remove rodent nests and eliminate points of ingress.

The central principles of tick-borne relapsing fever prevention are to remove rodents and their nests, exclude reintroduction of rodents into the building, and reduce exposure to the infected ticks 11.

Prevention is the best way to avoid tick-borne illness. Except for tick-borne encephalitis, there is no vaccine available to prevent tick-borne disease. Protective clothing, such as long pants, long sleeves, and closed shoes should be worn in tick-infested areas, particularly in the late spring in summer when most cases occur. Pant legs should be tucked into socks when walking through high grass and brush. Permethrin, which is an insecticide, may be applied to clothing and is quite effective in repelling ticks. Other tick repellents such as diethyl-m-toluamide (DEET) may be applied to skin or clothing, with variable effectiveness. DEET can be quite toxic, with effects ranging from local skin irritation to seizures. DEET should be avoided in infants.

Use insect repellents and protective clothing when in tick-infested areas. Tuck pant legs into socks. Carefully check the skin and hair after being outside and remove any ticks you find.

If you find a tick on your child, write the information down and keep it for several months. Many tick-borne diseases do not show symptoms right away, and you may forget the incident by the time your child becomes sick with a tick-borne disease.

Before you go outdoors

- Know where to expect ticks. Ticks live in grassy, brushy, or wooded areas, or even on animals. Spending time outside walking your dog, camping, gardening, or hunting could bring you in close contact with ticks. Many people get ticks in their own yard or neighborhood.

- Treat clothing and gear with products containing 0.5% permethrin. Permethrin can be used to treat boots, clothing and camping gear and remain protective through several washings. Alternatively, you can buy permethrin-treated clothing and gear.

- Use Environmental Protection Agency (EPA)-registered insect repellents containing DEET, picaridin, IR3535, Oil of Lemon Eucalyptus (OLE), para-menthane-diol (PMD), or 2-undecanone (https://www.epa.gov/insect-repellents). EPA’s helpful search tool (https://www.epa.gov/insect-repellents/find-repellent-right-you) can help you find the product that best suits your needs. Always follow product instructions.

- DO NOT use insect repellent on babies younger than 2 months old.

- DO NOT use products containing OLE or PMD on children under 3 years old.

Avoid contact with ticks

- Avoid wooded and brushy areas with high grass and leaf litter.

- Walk in the center of trails.

After you come indoors

Check your clothing for ticks. Ticks may be carried into the house on clothing. Any ticks that are found should be removed. Tumble dry clothes in a dryer on high heat for 10 minutes to kill ticks on dry clothing after you come indoors. If the clothes are damp, additional time may be needed. If the clothes require washing first, hot water is recommended. Cold and medium temperature water will not kill ticks.

Examine gear and pets. Ticks can ride into the home on clothing and pets, then attach to a person later, so carefully examine pets, coats, and daypacks.

Shower soon after being outdoors. Showering within two hours of coming indoors has been shown to reduce your risk of getting Lyme disease and may be effective in reducing the risk of other tickborne diseases. Showering may help wash off unattached ticks and it is a good opportunity to do a tick check.

Check your body for ticks after being outdoors. Conduct a full body check upon return from potentially tick-infested areas, including your own backyard. Use a hand-held or full-length mirror to view all parts of your body. Check these parts of your body and your child’s body for ticks:

- Under the arms

- In and around the ears

- Inside belly button

- Back of the knees

- In and around the hair

- Between the legs

- Around the waist

Figure 2. Check your body for ticks

Preventing tick bites

Tick exposure can occur year-round, but ticks are most active during warmer months (April-September). Know which ticks are most common in your area (see geographic distribution of ticks that bite humans below).

When spending time outdoors, make these easy precautions part of your routine:

- Wear enclosed shoes and light-colored clothing with a tight weave to spot ticks easily

- Scan clothes and any exposed skin frequently for ticks while outdoors

- Stay on cleared, well-traveled trails

- Use insect repellant containing DEET (Diethyl-meta-toluamide) on skin or clothes if you intend to go off-trail or into overgrown areas

- Avoid sitting directly on the ground or on stone walls (havens for ticks and their hosts)

- Keep long hair tied back, especially when gardening

- Do a final, full-body tick-check at the end of the day (also check children and pets)

When taking the above precautions, consider these important facts:

- If you tuck long pants into socks and shirts into pants, be aware that ticks that contact your clothes will climb upward in search of exposed skin. This means they may climb to hidden areas of the head and neck if not intercepted first; spot-check clothes frequently.

- Clothes can be sprayed with either DEET or Permethrin. Only DEET can be used on exposed skin, but never in high concentrations; follow the manufacturer’s directions.

- Upon returning home, clothes can be spun in the dryer for 20 minutes to kill any unseen ticks

- A shower and shampoo may help to remove crawling ticks, but will not remove attached ticks. Inspect yourself and your children carefully after a shower. Keep in mind that nymphal deer ticks are the size of poppy seeds; adult deer ticks are the size of apple seeds.

Any contact with vegetation, even playing in the yard, can result in exposure to ticks, so careful daily self-inspection is necessary whenever you engage in outdoor activities and the temperature exceeds 45° F (the temperature above which deer ticks are active). Frequent tick checks should be followed by a systematic, whole-body examination each night before going to bed. Performed consistently, this ritual is perhaps the single most effective current method for prevention of Lyme disease.

Finally, prevention is not limited to personal precautions. Those who enjoy spending time in their yards can reduce the tick population around the home by:

- keeping lawns mowed and edges trimmed

- clearing brush, leaf litter and tall grass around houses and at the edges of gardens and open stone walls

- stacking woodpiles neatly in a dry location and preferably off the ground

- clearing all leaf litter (including the remains of perennials) out of the garden in the fall

- having a licensed professional spray the residential environment (only the areas frequented by humans) with an insecticide in late May (to control nymphs) and optionally in September (to control adults).

Why you shouldn’t remove the rodent nests yourself

Activities that put you in contact with deer mouse droppings, urine, saliva, or nesting materials can place you at risk for infection with Hantavirus Pulmonary syndrome, a potentially fatal condition. Hantavirus is spread when virus-containing particles from deer mouse urine, droppings, or saliva are stirred into the air. Infection occurs when you breathe in virus particles.

What do I do if I find a tick on my skin?

Don’t panic. Use fine-tipped tweezers to grasp the tick as close to the skin’s surface as possible. Pull up with steady, even pressure. Be careful not to squeeze or twist the tick body. Sometimes parts of the tick remain in the skin. You can leave them alone or carefully remove them the same way you would a splinter. Do not use heat (such as a lit match), petroleum jelly, or other methods to try to make the tick “back out” on its own. These methods are not effective.

Wash the area where the tick was attached thoroughly with soap and water. Keep an eye on the area for a few weeks and note any changes. Call your doctor if you develop a fever or other symptoms of tick-borne relapsing fever. Be sure to tell your doctor that you were bitten by a tick and when it happened.

How to remove a tick

If you find a tick attached to your skin, there’s no need to panic—the key is to remove the tick as soon as possible. There are several tick removal devices on the market, but a plain set of fine-tipped tweezers work very well.

To remove a tick, follow these steps:

- Using a pair of fine-tipped or pointy tweezers, grasp the tick by the head or mouth-parts right where they enter the skin. DO NOT grasp the tick by the body.

- Without jerking, pull firmly and steadily directly outward. DO NOT twist the tick out or apply petroleum jelly, a hot match, alcohol, nail polish or any other irritant to the tick in an attempt to get it to back out. Your goal is to remove the tick as quickly as possible–not waiting for it to detach. If the mouth-parts to break off and remain in the skin, remove the mouth-parts with tweezers. If you are unable to remove the mouth easily with clean tweezers, leave it alone and let the skin heal.

- Never crush a tick with your fingers. Dispose of a live tick by putting it in alcohol, placing it in a sealed bag/container, wrapping it tightly in tape, or flushing it down the toilet.

- Clean the bite wound with with rubbing alcohol or soap and water. Keep in mind that certain types of fine-pointed tweezers, especially those that are etched, or rasped, at the tips, may not be effective in removing nymphal deer ticks. Choose unrasped fine-pointed tweezers whose tips align tightly when pressed firmly together.

Then, monitor the site of the bite for the appearance of a rash beginning 3 to 30 days after the bite. At the same time, learn about the other early symptoms of Lyme disease and watch to see if they appear in about the same timeframe. If a rash or other early symptoms develop, see a physician immediately. Be sure to tell the doctor about your recent tick bite, when the bite occurred, and where you most likely acquired the tick.

Figure 3. How to remove a tick

Relapsing fever symptoms

Symptoms of relapsing fever include:

- Bleeding

- Coma

- Headache

- Joint aches, muscle aches

- Nausea and vomiting

- Sagging on one side of the face (facial droop)

- Stiff neck

- Sudden high fever, shaking chills, seizure

- Vomiting

- Weakness, unsteady while walking

Tick-borne relapsing fever is a rare infection linked to sleeping in rustic cabins, particularly cabins in mountainous areas of the western United States. The main symptoms of tick-borne relapsing fever are recurring febrile episodes with high fever (e.g., 103° F [39.3 °C]) that last ~3 days and are separated by afebrile periods of ~7 days duration, headache, muscle and joint aches. Symptoms can reoccur, producing a telltale pattern of fever lasting roughly 3 days, followed by 7 days without fever, followed by another 3 days of fever. Each febrile episode ends with a sequence of symptoms collectively known as a “crisis.” During the “chill phase” of the crisis, patients develop very high fever (up to 106.7°F or 41.5°C) and may become delirious, agitated, tachycardic and tachypneic. Duration is 10 to 30 minutes. This phase is followed by the “flush phase”, characterized by drenching sweats and a rapid decrease in body temperature. During the flush phase, patients may become transiently hypotensive. Overall, patients who are not treated with antibiotic will experience several episodes of fever before illness resolves.

Findings on physical exam vary depending on the severity of illness and when the patient seeks medical care. Regardless, there are no findings specific for tick-borne relapsing fever. Patients typically appear moderately ill and may be dehydrated. Occasionally a macular rash or scattered petechiae may be present on the trunk and extremities. Less frequently, patients may have jaundice, hepatosplenomegaly, meningismus, and photophobia (Table 1). Although less common, infection with B. turicatae is especially likely to result in neurologic involvement.

Table 1. Selected symptoms and signs among patients with tick-borne relapsing fever, United States

| Symptom | Frequency of Symptom | Sign | Frequency of Sign |

|---|---|---|---|

| Headache | 94% | Confusion | 38% |

| Myalgia | 92% | Rash | 18% |

| Chills | 88% | Jaundice | 10% |

| Nausea | 76% | Hepatomegaly | 10% |

| Arthralgia | 73% | Splenomegaly | 6% |

| Vomiting | 71% | Conjunctival Injection | 5% |

| Abdominal pain | 44% | Eschar | 2% |

| Dry cough | 27% | Meningitis | 2% |

| Eye pain | 26% | Nuchal rigidity | 2% |

| Diarrhea | 25% | ||

| Photophobia | 25% | ||

| Neck pain | 24% |

Tick-borne relapsing fever in pregnancy

Tick-borne relapsing fever contracted during pregnancy can cause spontaneous abortion, premature birth, and neonatal death. The maternal-fetal transmission of Borrelia is believed to occur either transplacentally or while traversing the birth canal. In one study, perinatal infection with tick-borne relapsing fever was associated with lower birth weights, younger gestational age, and higher perinatal mortality 13.

In general, pregnant women have higher spirochete loads and more severe symptoms than nonpregnant women. Higher spirochete loads have not, however, been found to correlate with fetal outcome.

Relapsing fever possible complications

These complications may occur:

- Drooping of the face

- Coma

- Liver problems

- Inflammation of the thin tissue that surrounds the brain and spinal cord

- Inflammation of the heart muscle, which may lead to irregular heart rate

- Pneumonia

- Seizures

- Stupor

- Shock related to taking antibiotics (Jarisch-Herxheimer reaction, in which the rapid death of very large numbers of borrelia bacteria causes shock)

- Weakness

- Widespread bleeding

Relapsing fever diagnosis

Diagnosis of relapsing fever requires a careful history with attention to travel history and other geographic information, living conditions and the temporal pattern of the symptoms. Laboratory evaluation may include leukopenia or leukocytosis, as well as thrombocytopenia.

Diagnosis is confirmed by detection of Borrelia in Giemsa-stained blood films, serologic analysis or via PCR detection of the organism. These organisms are not identifiable in routine laboratory cultures. Diagnostic yield is highest with the earlier febrile episodes and decreases with each recurrence. Early in the course of illness, the number of spirochetes visible in the blood can reach 100,000/mm³. Between episodes and in later recurrences, the spirochetes may not be visible at all. Serology may also be used to diagnose tick-borne relapsing fever, particularly in situations in which diagnosis is suspected later in the course of illness. In that case, repeated testing with a rise in Immunoglobulin G (IgG) is suggestive of recent infection. However, these serologic tests cross-react with other spirochetes such as Leptospirosis and syphilis and must be interpreted in the setting of clinical symptoms 14. Furthermore, serologic testing for tick-borne relapsing fever is not standardized and results may vary by laboratory. Serum taken early in infection may be negative, so it is important to also obtain a serum sample during the convalescent period (at least 21 days after symptom onset). A change in serology results from negative to positive, or the development of an IgG response in the convalescent sample, is supportive of a tick-borne relapsing fever diagnosis. However, early antibiotic treatment may limit the antibody response. Patients with tick-borne relapsing fever may have false-positive tests for Lyme disease because of the similarity of proteins between the causative organisms. A diagnosis of tick-borne relapsing fever should be considered for patients with positive Lyme disease serology who have not been in areas endemic for Lyme disease..

Speciation of the relapsing fever Borrelia is typically not done in absence of a culture. The Borrelia species is often inferred from the location of the patient’s exposure. If the exposure occurred in a western state, at high elevation (1200-8000 feet), tick-borne relapsing fever is usually due to Borrelia hermsii. If the exposure occurred in a southern state, specifically Texas or Florida, at lower elevation, tick-borne relapsing fever is usually due to Borrelia turicatae.

Incidental laboratory findings include normal to increased white blood cell count with a left shift towards immature cells, a mildly increased serum bilirubin level, mild to moderate thrombocytopenia, elevated erythrocyte sedimentation rate (ESR), and slightly prolonged prothrombin time (PT) and partial thromboplastin time (PTT).

Relapsing fever treatment

Tick-borne relapsing fever spirochetes are susceptible to penicillin and other beta-lactam antimicrobials, as well as tetracyclines, macrolides, and possibly fluoroquinolones. The Centers for Disease Control and Prevention (CDC) has not developed specific treatment guidelines for tick-borne relapsing fever; however, experts generally recommend tetracycline 500 mg every 6 hours for 10 days as the preferred oral regimen for adults. Erythromycin, 500 mg (or 12.5 mg/kg) every 6 hours for 10 days is an effective alternative when tetracyclines are contraindicated. In children under eight years of age, penicillin or erythromycin are the preferred agents due to the concern of dental staining with doxycycline use. It is important to observe all patients during the first 4 hours after initiation of antibiotic therapy, as Jarisch-Herxheimer reaction is common. Jarisch-Herxheimer reaction is a sepsis-like response to the release of inflammatory contents from within the bacteria after lysis by antibiotics. In Jarisch-Herxheimer reaction, a worsening of symptoms with rigors, hypotension, and high fever, occurs in over 50% of cases and may be difficult to distinguish from a febrile crisis. It is rarely fatal and managed with supportive care. This reaction is more common in adolescents than in younger children. Cooling blankets and appropriate use of antipyretic agents may be indicated. In addition acute respiratory distress syndrome requiring intubation has been described recently in several patients undergoing treatment for tick-borne relapsing fever.

Parenteral therapy with ceftriaxone 2 grams per day for 10-14 days is preferred for patients with central nervous system involvement, similar to early neurologic Lyme disease. In contrast to tick-borne relapsing fever, louse-borne relapsing fever caused by Borrelia recurrentis can be treated effectively with a single dose of antibiotics.

Borrelia infections may also be self-limited and resolve without treatment in some cases 15.

Relapsing fever prognosis

Given appropriate treatment, most patients recover within a few days. Long-term complications of tick-borne relapsing fever are rare but include iritis, uveitis, cranial nerve and other neuropathies. Although there is limited information on the immunity of tick-borne relapsing fever, there have been patients who developed the disease more than once.

With antibiotic treatment, the mortality of epidemic relapsing fever (louse-borne relapsing fever) decreases from 10% to 40% to 2% to 4%. Mortality is attributed to myocarditis.

References- Snowden J, Oliver TI. Relapsing Fever. [Updated 2019 May 6]. In: StatPearls [Internet]. Treasure Island (FL): StatPearls Publishing; 2019 Jan-. Available from: https://www.ncbi.nlm.nih.gov/books/NBK441913

- Warrell DA. Louse-borne relapsing fever (Borrelia recurrentis infection). Epidemiol. Infect. 2019 Jan;147:e106.

- Dworkin MS, Schwan TG, Anderson DE,Jr, Borchardt SM. Tick-borne relapsing fever. Infect Dis Clin North Am. 2008;22:449-68, viii.

- Tick-borne Relapsing Fever (TBRF): Information for Clinicians. https://www.cdc.gov/relapsing-fever/clinicians

- Cases of Tick-borne Relapsing Fever – United States, 1990 – 2011. https://www.cdc.gov/relapsing-fever/resources/CasesTBRF.pdf

- Capinera JL. Arthropods as parasites of wildlife. In: Insects and Wildlife. Wiley-Blackwell; 2010:285-337.

- Margos G, Gofton A, Wibberg D, Dangel A, Marosevic D, Loh SM, Oskam C, Fingerle V. The genus Borrelia reloaded. PLoS ONE. 2018;13(12):e0208432

- Qiu Y, Nakao R, Hang’ombe BM, Sato K, Kajihara M, Kanchela S, Changula K, Eto Y, Ndebe J, Sasaki M, Thu MJ, Takada A, Sawa H, Sugimoto C, Kawabata H. Human Borreliosis Caused by a New World Relapsing Fever Borrelia-like Organism in the Old World. Clin. Infect. Dis. 2018 Nov 13

- Dworkin MS, Schwan TG, Anderson DE,Jr. Tick-borne relapsing fever in North America. Med Clin North Am. 2002;86:417-33, viii-ix.

- Dworkin MS, Shoemaker PC, Fritz CL, Dowell ME, Anderson DE,Jr. The epidemiology of tick-borne relapsing fever in the United States. Am J Trop Med Hyg. 2002;66:753-758.

- Assous MV, Wilamowski A. Relapsing fever borreliosis in Eurasia–forgotten, but certainly not gone! Clin Microbiol Infect. 2009;15:407-414.

- Dworkin, M. S., et al. Tick-borne relapsing fever in the northwestern United States and southwestern Canada. Clinical Infectious Diseases 1998; 26: 122-31.

- Jongen, V. H., J. van Roosmalen, et al. (1997). “Tick-borne relapsing fever and pregnancy outcome in rural Tanzania.” Acta Obstetricia et Gynecologica Scandinavica 76 (9):834-8.

- Warrell DA. Louse-borne relapsing fever (Borrelia recurrentis infection). Epidemiol. Infect. 2019 Jan;147:e106

- Mafi N, Yaglom HD, Levy C, Taylor A, O’Grady C, Venkat H, Komatsu KK, Roller B, Seville MT, Kusne S, Po JL, Thorn S, Ampel NM. Tick-Borne Relapsing Fever in the White Mountains, Arizona, USA, 2013-2018. Emerging Infect. Dis. 2019 Apr;25(4):649-653.