SMA syndrome

SMA syndrome also called superior mesenteric artery syndrome, is a rare digestive condition that occurs when the third portion of the duodenum (the first part of the small intestine) is compressed between two arteries (the abdominal aorta and the superior mesenteric artery) 1. This compression causes partial or complete blockage of the duodenum. Other names for SMA syndrome have included chronic duodenal ileus, Wilkie syndrome, arterio-mesenteric duodenal compression syndrome and cast syndrome 2. SMA syndrome symptoms vary based on severity, but can be severely debilitating 3. Symptoms may include abdominal pain, fullness, nausea, vomiting, and/or weight loss 4. The superior mesenteric artery provides blood supply to the majority of the small intestine. Compression from the superior mesenteric artery which is a muscular structure can prevent food from traveling through the duodenum and leads to bowel obstruction within the small intestine. Bowel obstructions means that food and other substances build up at the point of compression causing widening and damage to the duodenum and the stomach. SMA syndrome typically is due to loss of the mesenteric fat pad (fatty tissue that surrounds the superior mesenteric artery). The most common cause of SMA syndrome is significant weight loss as is often associated with medical disorders, psychological disorders, or surgery. In younger patients, it most commonly occurs after corrective spinal surgery for scoliosis 4. Delays in diagnosis may result in significant complications 4. As someone loses weight rapidly the normal fat that exists in the abdomen can shrink and cause the angle of the superior mesenteric artery to change, now putting pressure on the intestine. Prompt diagnosis and early treatment are essential to avoid significant complications.

Depending on the cause and severity, treatment options may include addressing the underlying cause, dietary changes (small feedings or a liquid diet), and/or surgery 5. Symptoms may not resolve completely after treatment 4.

SMA syndrome prevalence (the number of people with a disorder in a given population at a given time) is unknown. Researchers estimate that .1-.3% of people in the general population of the United States have the disorder 6. SMA syndrome occurs with greater frequency among teenagers and young adults, but can occur in individuals of any age. The disorder tends to affect women more often than men by a ratio of 3:2. SMA syndrome can affect individuals of any racial or ethic heritage 7.

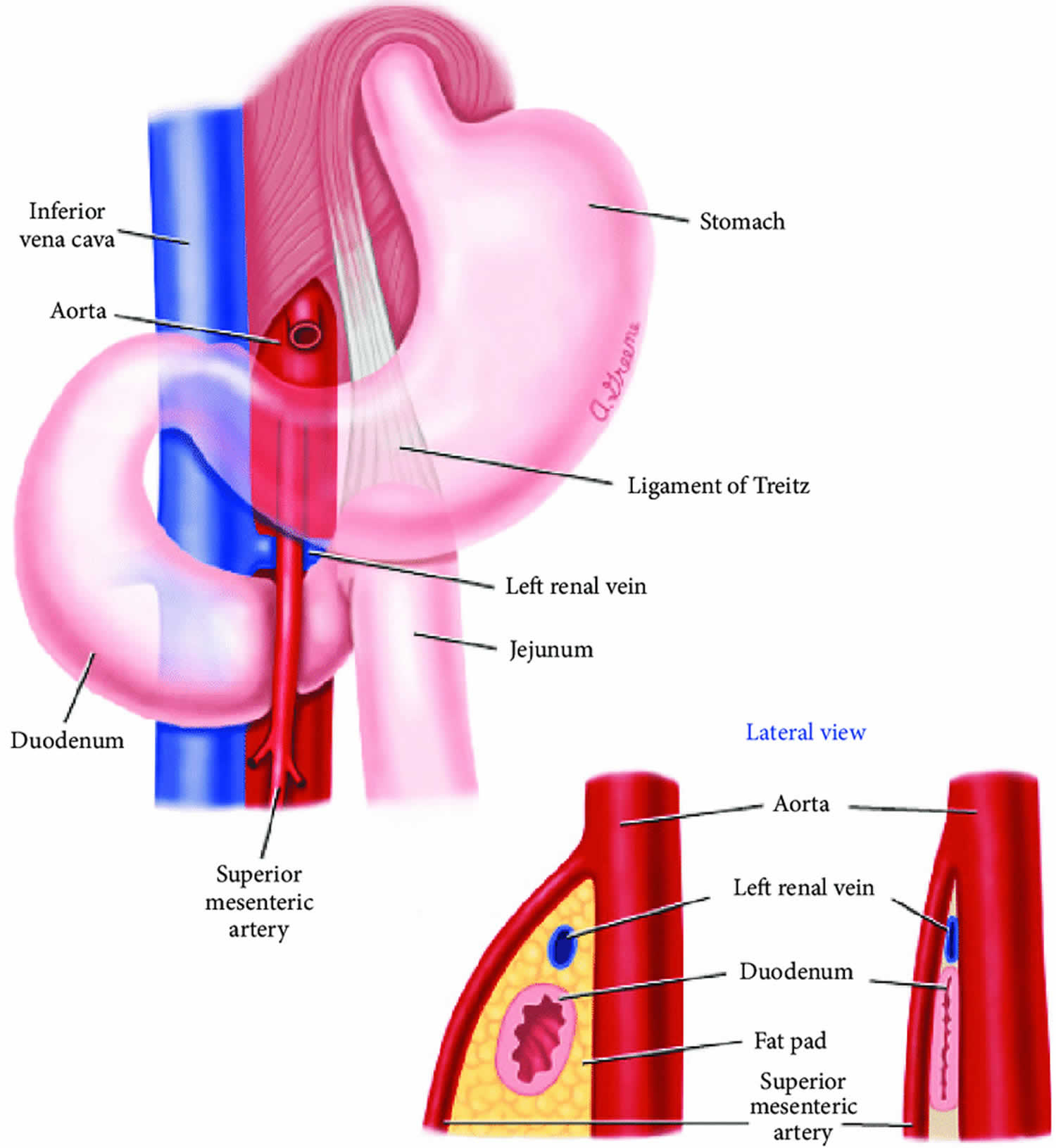

Figure 1. SMA syndrome

SMA syndrome causes

Superior mesenteric artery syndrome is caused when the third part of the duodenum is trapped or compressed between the two arteries – the aorta and the superior mesenteric artery. The intestine is a long, winding tube that connects the stomach to the anus. There is a small intestine and a large intestine. The small intestine connects directly to the stomach and is broken up into three sections – the duodenum, the jejunum, and the ileum.

The duodenum is the first part of the small intestine and connects directly to the stomach. The duodenum is sometimes described as having four sections. In SMA syndrome, the third section of the duodenum becomes compressed between the aorta and the superior mesenteric artery. Arteries are blood vessels that carry blood, filled with oxygen, away from the heart. The aorta is the largest blood vessel of the body. The superior mesenteric artery is one of the main arteries of the abdomen. It runs from the abdominal portion of the aorta to the third section of the small intestine, the ileum. Mesenteric refers to the mesentery, which is a fold of tissue that anchors the small intestine to the abdominal wall.

The angle at which the superior mesenteric artery comes out from the aorta is normally 25-60 degrees; in people with SMA syndrome, this angle can be reduced to as little as 6 degrees, causing the duodenum to become compressed between the two arteries. Symptoms can result if the angle is reduced below 25 degrees. The most common reason the angle of the superior mesenteric artery becomes reduced is the loss of the mesenteric fat pad normally found between these two arteries and that surrounds the superior mesenteric artery. A fat pad is a mass of closely or tightly packed fat cells. Most affected individuals have recently undergone significant weight loss.

Reduction of the angle of the superior mesenteric artery alone may not be sufficient to cause symptoms on its own. Researchers believe that there are several other factors necessary. In some people, there are distinct anatomical variations that are present from birth (congenital). This can include a superior mesenteric artery that comes out of the abdominal artery from a spot lower down than it normally would. Another anatomic variation is when the ligament of Treitz is abnormally short. This ligament is a muscle that connects and helps to support and hold the duodenum in place.

In younger patients, surgery for scoliosis is the most common cause of SMA syndrome. Surgery, which is done to straighten the spine, can also stretch the two arteries and displace the superior mesenteric artery. This reduces the angle between the two arteries and leads to compression of the duodenum. People who undergo orthopedic surgery, such as spinal surgery, and must be placed in a cast that runs from the torso to the feet (hip spica cast) or a full-body cast can also develop SMA syndrome. This is why the disorder is sometimes referred to as Cast syndrome.

Conditions that can cause rapid or significant weight loss are risk factors for SMA syndrome. This includes excessive exercise (such as with military exercise), people who have eating disorders, people who undergo gastric bypass surgery, and people who have diseases that cause a reduced ability to absorb nutrients such as fats, carbohydrates (sugars) vitamins, minerals, trace elements and fluids (malabsorption). Other conditions that affect the area of the body near the superior mesenteric artery also can increase the risk. Such conditions can include abdominal trauma, spinal cord injury, abdominal surgery, certain cancers (malignancies), aortic aneurysm, and chronic inflammation. People with extensive burns can also develop SMA syndrome due to fat and muscle wasting seen in this injury.

SMA syndrome symptoms

SMA syndrome symptoms include:

- abdominal fullness,

- bloating after meals,

- nausea and vomiting of partially digested food, and

- mid-abdominal “crampy” pain that may be relieved by the prone (lying on the stomach) or knee-chest position.

SMA syndrome signs and symptoms can vary greatly from one person to another. Sometimes, the symptoms are mild and build slowly over time, or they can develop rapidly. Without treatment, in some people, symptoms can become severely disabling. Generally, the initial symptoms are nonspecific, which means that the symptoms are common ones that can be associated with many different conditions. Symptoms sometimes come and go (intermittent).

SMA syndrome symptoms can include nausea, vomiting, abdominal pain, indigestion (dyspepsia), and early satiety, in which people feel full despite having very little food or drink. Vomiting is common and usually occurs within a half an hour of eating. Vomit often contains partially digested food and may contain bile (a yellowish, green liquid secreted by the liver that aids in absorption and digestion). Some people have symptoms associated with gastroesophageal reflux including heartburn, chest pain, and the regurgitation of food. Additional symptoms include significant, unintended weight loss, swelling (distention) of the abdomen, chronic belching, and pain or cramping in the central, upper region of the abdomen following eating (postprandial epigastric pain). Sometimes, the symptoms can be relieved when the person lies flat (prone). Symptoms can be severe enough that affected individuals will not want to eat or try to avoid eating as they normally would (food aversion).

Some affected individuals may also have Nutcracker syndrome, a rare condition in which the main vein the kidney (renal vein) is compressed between the superior mesenteric artery and the abdominal portion of the aorta. This condition may not cause any symptoms (asymptomatic) in some people. Common symptoms that can develop include blood in the urine (hematuria) and pain in the left flank area (upper abdomen, sides, and lower back).

SMA syndrome diagnosis

SMA syndrome diagnosis can be challenging because superior mesenteric artery syndrome is uncommon and symptoms can be nonspecific. Tests are done to differentiate the syndrome from other disorders that can cause similar clinical features.

A diagnosis of superior mesenteric artery syndrome is based upon identification of characteristic symptoms, a detailed patient history, a thorough clinical evaluation, and a variety of specialized tests. The symptoms of this disorder are nonspecific and this can lead to a delay in diagnosis.

Clinical testing and workup

Affected individuals will receive plain abdominal x-rays (radiographs) to rule out other conditions. These tests cannot diagnose SMA syndrome, but may show bloating or widening of the stomach (gastric distention).

Doctors may order an upper endoscopy examination. This examination allows doctors to view the upper portion of the digestive tract including the esophagus, stomach, and the duodenum. During this examination, doctors will run a thin, flexible tube down a person’s throat. This tube has a tiny camera attached to it that allows doctors to visually inspect these areas. This examination can reveal widening of the first two sections of the duodenum and abrupt narrowing or obstruction of the third section of the duodenum.

Computed tomography angiography (CTA) or a CT scan with intravenous contrast is one of the key tests as it can look for widening (dilatation) and obstruction of the bowel as well as measure the angle of the superior mesenteric artery as it comes out from the abdominal aorta (aortomesenteric angle), and can measure the distance from where the superior mesenteric artery comes out from the abdominal aorta to the duodenum (aortomesenteric distance). In patients who cannot receive IV contrast, a MRI with gadolinium can also give important information

Hypotonic duodenography is a specialized x-ray procedure that produces images of the duodenum. During this exam, a doctor runs a thin tube called a catheter through the nose and down the throat to the stomach and the small intestine. Then, barium is administered. Barium is a chalky, white, metallic element. X-rays cannot pass through barium so the x-ray film is able to outline structures or tissues in these areas.

A test called a doppler ultrasound has been used to diagnose SMA syndrome. Doppler ultrasonography is a non-invasive procedure in which reflected sound waves are used to create an image of structures within the body and allows physicians to see how blood flows through blood vessels. This test can evaluate the anatomy of the superior mesenteric artery and can measure the aortomesenteric angle.

SMA syndrome treatment

The treatment of superior mesenteric artery syndrome is directed toward the specific symptoms that are apparent in each individual. Treatment may require the coordinated efforts of a team of specialists. Pediatricians, general internists, doctors who specialize in the diagnosis and treatment of gastrointestinal disorders (gastroenterologists), surgeons, and other healthcare professionals may need to systematically and comprehensively plan an affected child’s treatment. Psychosocial support for the entire family is essential as well.

If possible, initial therapy is conservative. Weight gain is strongly encouraged whether through eating normally with a high-calorie diet, or through nutrition being delivering via a catheter directly inserted into a vein (parenterally). Weight gain alone can sometimes restore the mesenteric fat pad, thereby increasing the angle of the superior mesenteric artery as it leaves the abdominal aorta. Sometimes, doctors may recommend nasogastric decompression, in which a thin tube is passed down the nostrils to the stomach or small intestine. The tube is attached to a suction machine that allows the contents of the small intestine and stomach to be removed (gastric decompression). A nasogastric tube can help make individuals more comfortable and monitor fluid levels. The tube can also be used to deliver fluids and electrolytes.

If other therapeutic measures do not work, then surgery can be considered. The most commonly used surgical procedure is called duodenojejunostomy. This surgery bypasses the third section of duodenum, connecting an earlier section of the duodenum with jejunum, which is the second part of the small intestine. This procedure is sometimes performed along with cutting (dividing) the ligament of Treitz. Recently, surgeons have tried laparoscopic duodenojejunostomy. Laparoscopy involves examination of an area of the body with an illuminated viewing tube (laparoscope) inserted through small cuts (incisions). A tiny camera is attached to the tube, which allows surgeons to view the area in question. The camera as well as surgical instruments are passed through the tube. This allows for surgery to be performed with only a few small surgical cuts.

Sometimes, doctors may recommend Strong’s procedure. This is mainly recommended when the ligament of Treitz is too short. During this surgery, the duodenum is repositioned to the right of the superior mesenteric artery after the ligament of Treitz is divided. However, this procedure carries a 25% failure rate.

Sometimes, the duodenum is bypassed completely and the jejunum is connected directly to the stomach. This is called a gastrojejunostomy. This surgery has successfully been used to treat SMA syndrome, but is rarely used because it carries more risk than other procedures.

Finally, another option is SMA transposition where the SMA is reconnected to the aorta at a lower position so it cannot impact the intestine.

SMA syndrome prognosis

Superior mesenteric artery syndrome can be severely debilitating and may require long term management, medications, costly parenteral nutrition (intravenous feeding) and rigorous follow-up 3. The long-term outlook (prognosis) can depend on whether the condition is diagnosed and treated in a timely manner. The prognosis may be excellent if it is diagnosed quickly and appropriate therapy is given 1. However, the condition may go unrecognized until a person experiences symptoms for a long time 3. In the past, deaths have been reported due to complications including progressive dehydration, hypokalemia (low potassium), and oliguria (producing too little urine). Most deaths have been reported in people in whom the diagnosis was delayed or missed 1.

Other complications that may arise in people with SMAS include 1:

- Other electrolyte imbalances

- Malnutrition

- Hypotension

- Peptic ulcer disease

- Aspiration pneumonia.

- Superior Mesenteric Artery (SMA) Syndrome. https://emedicine.medscape.com/article/932220-overview

- Van Horne N, Jackson JP. Superior Mesenteric Artery Syndrome. [Updated 2019 Jun 4]. In: StatPearls [Internet]. Treasure Island (FL): StatPearls Publishing; 2019 Jan-. Available from: https://www.ncbi.nlm.nih.gov/books/NBK482209

- FJ Bohanon, O Nunez Lopez, BM Graham, LW Griffin, and RS Radhakrishnan. A Case Series of Laparoscopic Duodenojejunostomy for the Treatment of Pediatric Superior Mesenteric Artery Syndrome. Int J Surg Res. April, 2016; https://www.ncbi.nlm.nih.gov/pubmed/27747293

- Superior mesenteric artery syndrome. https://www.uptodate.com/contents/superior-mesenteric-artery-syndrome

- Superior Mesenteric Artery (SMA) Syndrome. International Foundation for Functional Gastrointestinal Disorders. https://iffgd.org/other-disorders/sma-syndrome.html

- Superior Mesenteric Artery Syndrome. https://rarediseases.org/rare-diseases/superior-mesenteric-artery-syndrome/

- Hillyard J, Solomon S, Kaspar M, Chow E, Smallfield G. Gastrointestinal: Reversal of superior mesenteric artery syndrome following pregnancy. J. Gastroenterol. Hepatol. 2019 Mar;34(3):486.