What is stridor

Stridor is an abnormal harsh, variable, high-pitched breathing sound 1. Stridor is caused by a blockage in the throat or voice box (larynx) at the level of the supraglottis, glottis, subglottis, or trachea 2. Stridor is most often heard when taking in a breath. It is important to remember that stridor is a symptom of some underlying problem or condition. Stridor can be inspiratory, expiratory, or biphasic; this may aid in determining the anatomic location of the airway obstruction. Inspiratory stridor is more likely to be caused by extrathorasic obstruction to air flow while expiratory stridor is more likely to occur with intrathorasic pathology. Stridor may be a sign of an emergency. See your doctor right away if there is unexplained stridor, especially in a child. Children are at higher risk of airway blockage because they have narrower airways than adults. In young children, stridor is a sign of airway blockage. Stridor must be treated right away to prevent the airway from becoming completely closed. The airway can be blocked by an object, swollen tissues of the throat or upper airway, or a spasm of the airway muscles or the vocal cords.

Typically, stridor is produced by the abnormal flow of air in the airways, usually the upper airways, and most prominently heard during inspiration. However, stridor can also be present during both inspiration and expiration. Stridor can be due to congenital malformations and anomalies as well as in the acute phase from life-threatening obstruction or infection. The diagnostic approach may include x-rays or bronchoscopy by a trained specialist to ascertain the etiology when there is diagnostic uncertainty. It should be noted that in infants and young children, a small amount of inflammation can result in significant and rapid airway obstruction 3.

Generally, stridor is more common in children than adults 1.

Stridor causes:

- Neonates: Congenital abnormalities present within the first month of life, with some presenting later in life.

- Infants to toddlers: The most common cause in this age group is croup or foreign body aspiration.

- Young adolescents: Vocal cord dysfunction, peritonsillar abscess

- Acute stridor: Epiglottitis, bacterial tracheitis will present with severe respiratory distress and secretions, and fever, if fever is not present then suspect foreign body aspiration or anaphylaxis

- Subacute stridor: Croup will present with intermittent stridor

With croup, for example, the peak incidence is between 6 months to 36 months, where there are about 5 to 6 cases per 100 toddlers. There is also a slight male predominance of 1.4:1.

Moreover, foreign body aspiration accounts for more than 17,000 emergency department visits per year in the United States, with most cases occurring before the age of 3 years 4.

Differential diagnosis of stridor can include infectious, inflammatory, or anatomical causes. Your emergency physician should always recognize croup, epiglottitis, anaphylaxis, bacterial tracheitis, abscess, and foreign aspiration as a cause of stridor. The differential can be narrowed down based on the patients presenting age and the duration of the stridor.

Stridor pathophysiology:

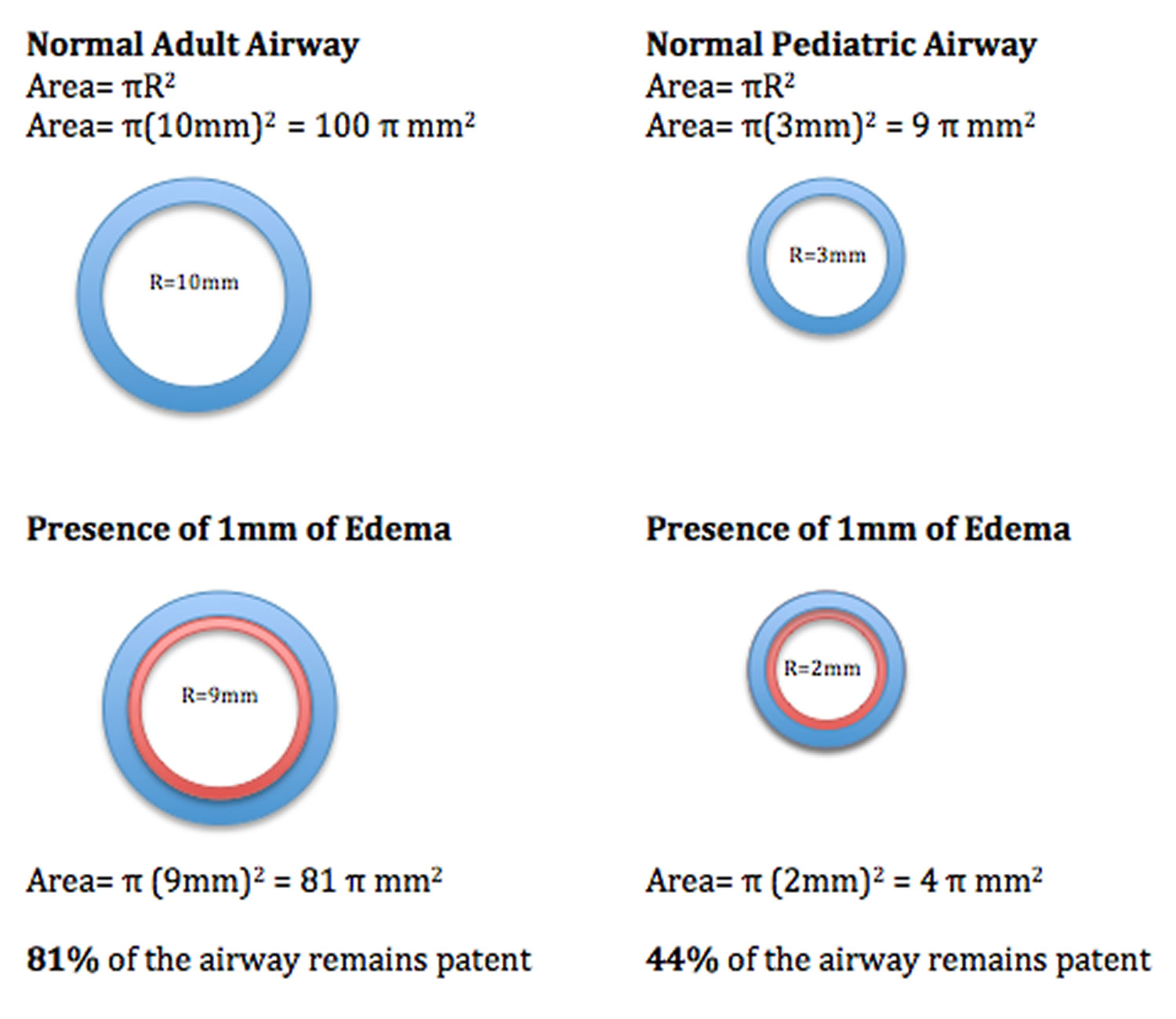

- Stridor is caused by restriction of airflow through the upper airways. As the radius of the airway deceases by a factor of 1, the area of the airway decreases by a power of 4.

- The decrease in the area of the airway leads to a proportional increase in velocity due to the Venturi Effect (this same effect can be seen when a thumb is placed over the end of a garden hose). The increase in velocity creates a low-pressure vacuum, exacerbating airway collapse (Bernoulli Principle).

- This ultimately leads to increased airway resistance, increase effort of breathing, and the clinical finding of stridor.

- Due to the smaller diameter of the pediatric airway compared to that of adults, even minor changes can lead to a marked reduction in overall airway caliber.

- As demonstrated in the diagram below, 1 mm of edema in the average adult airway leaves 81% of the cross-sectional area patent, while the same 1 mm of edema in a pediatric patient results in only 44% patency.

Specific treatment of stridor will be determined by your child’s doctor based on:

- Your child’s age, overall health and medical history

- Cause of the stridor

- Extent of the condition

- Your child’s tolerance for specific medications, procedures or therapies

- Expectations for the course of the condition

- Your opinion or preference

Treatment may include:

- Referral to an ear, nose, and throat specialist (otolaryngologist) for further evaluation (if your child has a history of stridor)

- Surgery

- Medications by mouth or injection (to help decrease the swelling in the airways)

Hospitalization and emergency surgery may be necessary depending on the severity of the stridor.

In an emergency, your doctor will check the your temperature, pulse, breathing rate, and blood pressure, and may need to do abdominal thrusts.

A breathing tube may be needed if the person can’t breathe properly.

After the person is stable, the doctor may ask about the person’s medical history, and perform a physical exam. This includes listening to the lungs.

Parents or caregivers may be asked the following medical history questions:

- Is the abnormal breathing a high-pitched sound?

- Did the breathing problem start suddenly?

- Could the child have put something in their mouth?

- Has the child been ill recently?

- Is the child’s neck or face swollen?

- Has the child been coughing or complaining of a sore throat?

- What other symptoms does the child have? (For example, nasal flaring or a bluish color to the skin, lips, or nails)

- Is the child using chest muscles to breathe (intercostal retractions)?

Tests that may be done include:

- Arterial blood gas analysis

- Bronchoscopy

- Chest CT scan

- Laryngoscopy (examination of the voice box)

- Pulse oximetry to measure blood oxygen level

- X-ray of the chest or neck

Stridor key points

- Stridor is a noisy or high-pitched sound with breathing. It is usually caused by a blockage or narrowing in your child’s upper airway.

- Some common causes of stridor in children are infections and defects in the child’s nose, throat, larynx, or trachea that the child was born with.

- The sound of stridor depends on where the blockage is in the upper respiratory tract.

- Inspiratory stridor is often a medical emergency.

- Assessment of vital signs and degree of respiratory distress is the first step.

- The child may need a hospital stay and emergency surgery, depending on how severe the stridor is.

- In some cases, securing the airway may be necessary before or in parallel with the physical examination.

- Acute epiglottitis is uncommon in children who have received Haemophilus influenzae type B (HiB) vaccine.

- If left untreated, stridor can block the child’s airway. This can be life-threatening or even cause death.

Figure 1. Stridor causes

[Source 1 ]See your child’s healthcare provider if your child makes a noisy or high-pitched sound while breathing.

Call your local emergency services number or get medical help right away if your child has signs or symptoms of severe blockage of the airway. These signs may include:

- Gasping for air, choking

- Nostrils widening when breathing

- Sinking in of the areas between the ribs when breathing

- Change in behavior

- Bluish-colored skin

- Loss of consciousness

Stridor anatomy

- The upper airway can be divided into two anatomic regions: the intrathorasic and extrathorasic airway.

- The extrathorasic airway is defined as the region above the superior thoracic aperture including:

- The nasopharynx, epiglottis, larynx, vocal folds, and upper segment of trachea.

- The narrowest portion of the extrathorasic airway in pediatric patients is the cricoid cartilage.

- The intrathroasic airway is defined as the region below the superior thoracic aperture including:

- The lower portion of the trachea and the mainstem bronchi.

- The extrathorasic airway is defined as the region above the superior thoracic aperture including:

- Pathology of the extrathorasic airway is the most common cause of stridor in the pediatric population.

- Generally, Inspiratory stridor is more likely to be caused by extrathorasic obstruction to air flow while expiratory stridor is more likely to occur with intrathorasic pathology.

- The pediatric airway differs from that of an adult in four ways:

- The position of the larynx is more anterior (often making direct visualization more difficult).

- The vocal cords are shorter and more concave.

- The epiglottis is more ‘U-shaped’ allowing it to protrude further into the pharynx.

- The cricoid cartilage is the narrowest portion of the airway in patients under 8 years of age.

Figure 2. Larynx and pharynx anatomy

Figure 3. Larynx (voice box) anatomy

Stridor vs Wheeze

Wheeze is a musical, high-pitched, adventitious sound generated anywhere from the larynx to the distal bronchioles during either expiration or inspiration 5. Stridor is a higher pitched and higher amplitude sound that is due to turbulent air flow around a region of upper airway obstruction. It is typically an inspiratory sound that is far more pronounced when auscultated over the trachea than the thorax. Wheezing is the symptomatic manifestation of any disease process that causes airway obstruction. Modern-day, computerized, waveform analysis has allowed doctors to characterize wheeze with more precision and given us its definition as a sinusoidal waveform, typically between 100 Hz and 5000 Hz with a dominant frequency of at least 400 Hz, lasting at least 80 milliseconds 5. Wheeze may be audible without the aid of a stereoscope when the sound is loud, but in most cases, wheezes are auscultated with a stethoscope.

The presence of wheezing does not always mean that the patient has asthma, and a proper history and physical exam are required to make the diagnosis.

Approximately 25 to 30 percent of infants will have at least one wheezing episode, and nearly one half of children have a history of wheezing by six years of age 6. The most common causes of wheezing in children include asthma, allergies, infections, gastroesophageal reflux disease (GERD), and obstructive sleep apnea (OSA) 7. Less common causes include congenital abnormalities, foreign body aspiration, and cystic fibrosis. Historical data that help in the diagnosis include family history, age at onset, pattern of wheezing, seasonality, suddenness of onset, and association with feeding, cough, respiratory illnesses, and positional changes. A focused examination and targeted diagnostic testing guided by clinical suspicion also provide useful information. Children with recurrent wheezing or a single episode of unexplained wheezing that does not respond to bronchodilators should undergo chest radiography. Children whose history or physical examination findings suggest asthma should undergo diagnostic pulmonary function testing.

Causes of wheezing in children and infants

Common causes of wheezing

- Allergies

- Asthma or reactive airway disease

- Gastroesophageal reflux disease

- Infections

- Bronchiolitis

- Bronchitis

- Pneumonia

- Upper respiratory infection

- Obstructive sleep apnea

Uncommon causes of wheezing

- Bronchopulmonary dysplasia

- Foreign body aspiration

Rare causes of wheezing

- Bronchiolitis obliterans

- Congenital vascular abnormalities

- Congestive heart failure

- Cystic fibrosis

- Immunodeficiency diseases

- Mediastinal masses

- Primary ciliary dyskinesia

- Tracheobronchial anomalies

- Tumor or malignancy

- Vocal cord dysfunction

Wheezing diagnosis

History should be targetted toward the various etiologies of wheezing listed above. For example, patients who have had head and neck cancer surgery and/or radiation may develop vocal cord paralysis. Additionally, a prior history of endotracheal intubation can alert one to the possibility of tracheal, subglottic stenosis.

Physical examination of the trachea and thorax will identify wheeze. Wheeze associated with asthma is most commonly heard during expiration; however, wheeze is neither sensitive or specific for asthma, so the wheezes can certainly extend into inspiration also. Upper airway obstruction from tonsilar hypertrophy can be evaluated with an oral examination and palpation of the neck could identify a goiter.

Diagnostic testing

When wheezing is heard, some work up is required because it is an abnormal sound. The first imaging test of choice in a patient with wheezing is a chest x-ray to look for a foreign body or a lesion in the central airway. In the non-acute setting, if asthma is suspected, the next step is to obtain baseline pulmonary function tests with bronchodilator administration. Following this, it may be necessary perform an airway challenge test with a bronchoconstrictive agent such as methacholine. If the wheezing resolves with a bronchodilation agent, a tumor or mass as the cause is a much less likely consideration. If there is no resolution after a breathing treatment, and a tumor or mass is suspected, then a CT scan of the chest and bronchoscopy may be required if possible malignancy is suspected on CT.

Wheezing treatment

Treatment predominantly revolves around the suspected cause of the wheezing. The ubiquitous approach to ensuring Airway, Breathing, and Circulation (ABCs) are stable is the priority. Those with signs of impending respiratory failure may require either noninvasive positive pressure ventilation or invasive mechanical ventilation following endotracheal intubation. In cases of anaphylaxis, epinephrine would be required. Nebulized, short-acting, b2 agonist such as albuterol and nebulized short-acting muscarinic antagonists are often administered while further workup is being performed.

Stridor causes

The causes for stridor differ depending on whether the patient is infant or an adult. For infants and children, the most common causes of acute stridor include croup, foreign body aspiration. However, there are many other causes. The cause of stridor can further be differentiated based on acuity and based on congenital versus noncongenital causes.

In a study of 219 patients with the primary presenting symptom of stridor, the principle diagnosis was due to 8:

- Congenital anomalies: 87%

- Laryngeal: 75%

- Tracheal: 16

- Bronchial: 5%

- Traumatic 5.5%

- Infectious 5.5%

Common causes of stridor include:

- Airway injury

- Allergic reaction

- Problem breathing and a barking cough (croup)

- Diagnostic tests such as bronchoscopy or laryngoscopy

- Epiglottitis, inflammation of the cartilage that covers the windpipe

- Inhaling an object such as a peanut or marble (foreign body aspiration)

- Swelling and irritation of the voice box (laryngitis)

- Neck surgery

- Use of a breathing tube for a long time

- Secretions such as phlegm (sputum)

- Smoke inhalation or other inhalation injury

- Swelling of the neck or face

- Swollen tonsils or adenoids (such as with tonsillitis)

- Vocal cord cancer

Causes of stridor in children according to site of obstruction 9

- Nose and pharynx

- Choanal atresia

- Lingual thyroid or thyroglossal cyst

- Macroglossia

- Micrognathia

- Hypertrophic tonsils/adenoids

- Retropharyngeal or peritonsillar abscess.

- Retropharyngeal abscess is a complication of bacterial pharyngitis that is observed in children younger than 6 years. The patient presents with abrupt onset of high fevers, difficulty swallowing, refusal to feed, sore throat, hyperextension of the neck, and respiratory distress 10.

- Peritonsillar abscess is an infection in the potential space between the superior constrictor muscles and the tonsil. It is common in adolescents and preadolescents. The patient develops severe throat pain, trismus, and trouble with swallowing or speaking.

- Larynx

- Laryngomalacia. Laryngomalacia is the most common cause of inspiratory stridor in the neonatal period and early infancy and accounts for as many as 75% of all cases of stridor 11. Stridor may be exacerbated by crying or feeding. Placing the child in a prone position (the person lies flat with the chest down and the back up) with the head up alleviates the stridor; a supine position (lying on the back) exacerbates the stridor. Laryngomalacia is usually benign and self-limiting and improves as the child reaches age 1 year. In cases where significant obstruction or lack of weight gain is present, surgical correction or supraglottoplasty may be considered if the clinician has observed tight mucosal bands holding the epiglottis close to the true vocal cords or redundant mucosa overlying the arytenoids 12. It should be kept in mind that the presentation of laryngomalacia in older children (late-onset laryngomalacia) can differ from that of congenital laryngomalacia 13. Possible manifestations of late-onset laryngomalacia include obstructive sleep apnea syndrome, exercise-induced stridor, and even dysphagia. Supraglottoplasty can be an effective treatment option.

- Laryngeal web, cyst or laryngocele.

- Laryngeal webs are caused by an incomplete recanalization of the laryngeal lumen during embryogenesis. Most (75%) are in the glottic area. Infants with laryngeal webs have a weak cry and biphasic stridor. Intervention is recommended in the setting of significant obstruction and includes cold knife or CO2 laser ablation 14.

- Laryngeal cysts are a less frequent cause of stridor. They are usually found in the supraglottic region in the epiglottic folds. Patients may present with stridor, hoarse voice, or aphonia. Cysts may cause obstruction of the airway lumen if they are very large.

- Laryngotracheobronchitis (viral croup). Croup is the most common cause of acute stridor in children aged 6 months to 2 years. The patient has a barking cough that is worse at night and may have low-grade fever 15.

- Acute spasmodic laryngitis (spasmodic croup). Spasmodic croup occurs most commonly in children aged 1-3 years. The presentation may be identical to that of croup.

- Epiglottitis. Epiglottitis is a medical emergency that occurs most commonly in children aged 2-7 years. Clinically, the patient experiences an abrupt onset of high-grade fever, sore throat, dysphagia, and drooling.

- Vocal cord paralysis. Vocal cord dysfunction is probably the second most common cause of stridor in infants. Unilateral vocal cord paralysis can be either congenital or secondary to birth or surgical trauma (eg, from cardiothoracic procedures). Patients with a unilateral vocal cord paralysis present with a weak cry and biphasic stridor that is louder when awake and improves when lying with the affected side down. Bilateral vocal cord paralysis is a more serious entity. Patients usually present with aphonia and a high-pitched biphasic stridor that may progress to severe respiratory distress. This condition is usually associated with CNS abnormalities, such as Arnold-Chiari malformation or increased intracranial pressure. Vocal cord paralysis in infants usually resolves within 24 months.

- Laryngotracheal stenosis

- Intubation

- Foreign body. Aspiration of foreign body is common in children aged 1-2 years. Usually, foreign bodies are food (eg,nuts, hot dogs, popcorn, or hard candy) that is inhaled. A history of coughing and choking that precedes development of respiratory symptoms may be present 16.

- Cystic hygroma

- Subglottic hemangioma. Laryngeal hemangiomas (glottic or subglottic) are rare, and half of them are accompanied by cutaneous hemangiomas in the head and neck. Patients usually present with inspiratory or biphasic stridor that may worsen as the hemangioma enlarges. Typically, hemangiomas present in the first 3-6 months of life during the proliferative phase and regress by age 12-18 months. Medical or surgical intervention for laryngeal hemangiomas is based on the severity of symptoms. Treatment options consist of oral steroids, intralesional steroids, laser therapy with CO2 or potassium-titanyl-phosphate (KTP) lasers, and surgical resection. Oral propranolol has proved to be an effective medical treatment in the appropriate population (it is contraindicated in children with severe asthma, diabetes, or heart disease) 17.

- Patients with subglottic stenosis can present with inspiratory or biphasic stridor. Symptoms can be evident at any time during the first few years of life. If symptoms are not present in the neonatal period, this condition may be misdiagnosed as asthma. Congenital subglottic stenosis occurs when an incomplete canalization of the subglottis and cricoid rings causes a narrowing of the subglottic lumen. Acquired stenosis is most commonly caused by prolonged intubation.

- Laryngeal papilloma. Laryngeal papillomas occur secondary to vertical transmission of the human papillomavirus from maternal condylomata or infected vaginal cells to the pharynx or larynx of the infant during the birth process. These are primarily treated with surgical excision, with questionable use of cidofovir and interferon in refractory cases 18. A high rate of recurrence of disease is noted, with a need for multiple surgical debridements and a small risk of malignancy (5% malignant degeneration).

- Angioneurotic edema

- Allergic reaction (ie, anaphylaxis) occurs within 30 minutes of an adverse exposure. Hoarseness and inspiratory stridor may be accompanied by symptoms (eg, dysphagia, nasal congestion, itching eyes, sneezing, and wheezing) that indicate the involvement of other organs.

- Laryngospasm (hypocalcemic tetany)

- Laryngeal dyskinesia, exercise-induced laryngomalacia, and paradoxical vocal cord motion are other neuromuscular disorders that may be considered.

- Psychogenic stridor

- Trachea

- Tracheomalacia. Tracheomalacia is caused either by a defect on the cartilage, resulting in loss of the rigidity necessary to keep the tracheal lumen patent, or by an extrinsic compression of the trachea. Tracheomalacia, if present in the proximal (extrathoracic) trachea, can be associated with inspiratory stridor. If it is present in the distal (intrathoracic) trachea, it is associated more with expiratory noise.

- Bacterial tracheitis. Bacterial tracheitis is relatively uncommon and mainly affects children younger than 3 years. It is a secondary infection (most commonly due to Staphylococcus aureus) that follows a viral process (commonly croup or influenza).

- Tracheal stenosis can be congenital or secondary to extrinsic compression. Congenital stenosis is usually related to complete tracheal rings, is characterized by a persistent stridor, and necessitates surgery based on symptom severity.

- External compression. The most common extrinsic causes of trachea stenosis include vascular rings, slings, and a double aortic arch that encircles the trachea and esophagus. Pulmonary artery slings are also associated with complete tracheal rings. External compression can also result in tracheomalacia. Patients usually present during the first year of life with noisy breathing, intercostal retractions, and a prolonged expiratory phase.

Congenital (problems present at birth) causes of stridor in children

- Nasal deformities such as choanal atresia, choanal atresia, septum deformities, turbinate hypertrophy, vestibular atresia, or vestibular stenosis

- Craniofacial anomalies such as Pierre Robin or Apert syndromes, or conditions causing macroglossia

- Laryngeal anomalies such as laryngomalacia, laryngeal webs, laryngeal cysts, laryngeal clefts, subglottic stenosis, vocal cord paralysis, tracheal stenosis, tracheomalacia

- Laryngomalacia. Parts of the larynx are floppy and collapse causing partial airway obstruction. The child will usually outgrow this condition by the time he or she is 18 months old. This is the most common congenital cause of stridor. Very rarely children may need surgery.

- Subglottic stenosis. The larynx (voice box) may become too narrow below the vocal cords. Children with subglottic stenosis are usually not diagnosed at birth, but more often, a few months after, particularly if the child’s airway becomes stressed by a cold or other virus. The child may eventually outgrow this problem without intervention. Most children will need a surgical procedure if the obstruction is severe.

- Subglottic hemangioma. A type of mass that consists mostly of blood vessels. Subglottic hemangioma grows quickly in the child’s first few months of life. Some children may outgrow this problem, as the hemangioma will begin to get smaller after the first year of life. Most children will need surgery if the obstruction is severe. This condition is very rare.

- Vascular rings. The trachea, or windpipe, may be compressed by another structure (an artery or vein) around the outside. Surgery may be required to alleviate this condition.

Most common cause of chronic stridor in infants is laryngomalacia 19.

Noncongenital causes of stridor in children

- Acute: Foreign body aspiration, airway burns, bacterial tracheitis, epiglottitis, anaphylaxis, croup.

- Subacute: Peritonsillar abscess, retropharyngeal abscess.

- Chronic: Vocal cord dysfunction, laryngeal spasm, neoplasm.

Infectious causes:

- Croup. Croup is an infection caused by a virus that leads to swelling in the airways and causes breathing problems. Croup is caused by a variety of different viruses, most commonly the parainfluenza virus.

- Epiglottitis. Epiglottitis is an acute life-threatening bacterial infection that results in swelling and inflammation of the epiglottis. (The epiglottis is an elastic cartilage structure at the root of the tongue that prevents food from entering the windpipe when swallowing.) This causes breathing problems that can progressively worsen which may ultimately lead to airway obstruction. There is so much swelling that air cannot get in or out of the lungs, resulting in a medical emergency. Epiglottitis is usually caused by the bacteria Haemophilus influenzae, and now is rare because infants are routinely vaccinated against this bacteria. The vaccine is recommended for all infants.

- Bronchitis. Bronchitis is an inflammation of the breathing tubes (airways), called bronchi, which causes increased production of mucus and other changes. Acute bronchitis is usually caused by infectious agents such as bacteria or viruses. It may also be caused by physical or chemical agents — dusts, allergens, strong fumes — and those from chemical cleaning compounds or tobacco smoke.

- Severe tonsillitis. The tonsils are small, round pieces of tissue that are located in the back of the mouth on the side of the throat. Tonsils are thought to help fight infections by producing antibodies. The tonsils can usually be seen in the throat of your child by using a light. Tonsillitis is defined as inflammation of the tonsils from infection.

- Abscess in the back of the throat (retropharyngeal abscess). An abscess in the throat is a collection of pus surrounded by inflamed tissue. If the abscess is large enough, it may narrow the airway to a critically small opening.

Traumatic causes:

- Foreign bodies in the ear, nose and breathing tract may cause symptoms to occur. Foreign bodies are any objects placed in the ear, nose or mouth that do not belong there. For example, a coin in the trachea (windpipe) may close off breathing passages and result in suffocation and death.

- Fractures in the neck.

- Swallowing a harmful substance that may cause damage to the airways.

Age of onset

Age of onset is a key factor in developing a differential diagnosis for stridor in pediatric patients. Congenital abnormalities of the upper airway typically present in the first few weeks to months of life and are the most common causes of stridor (87%).

- Common causes of stridor at birth include: vocal cord paralysis, choanal atresia, laryngeal web, or vascular ring.

- Common causes of stridor during the first few weeks of life include: laryngomalacia, tracheomalacia, and subglottic stenosis

- Common causes of stridor from 1-4 years of age: croup, epiglottitis, foreign body aspiration

- Stridor occurring in toddlers is most likely due to foreign body aspiration.

- Infectious causes can occur in children of all ages.

Acuity of onset

- Acute onset of stridor in toddlers should raise the suspicion for a foreign body aspiration. In some children, stridor will not appear for several due to reactive inflammation of the airway, so a remote history of aspiration should be evaluated in the patient’s history.

- The onset of stridor along with fever, chills, and toxic appearance should allude to an infectious cause of epiglottitis or tracheitis.

- Chronic stridor may represent an indolent structural process such as laryngomalacia, laryngeal web, or laryngotracheal stenosis.

Stridor pathophysiology

The pathophysiology of stridor is based upon the anatomic location involved as well as the underlying disease process. Narrowowing of the supraglottic areas can occur rapidly because there is no cartilage in these areas. The subglottic area is of most concern in infants in which minimal airway narrowing here can result in dramatic increases in airway resistance.

Inspiratory stridor

An obstruction in the extrathoracic region causes inspiratory stridor. During inspiration, the intratracheal pressure falls below the atmospheric pressure, causing a collapse of the airway.

Expiratory stridor

An obstruction in the intrathoracic region causes expiratory stridor. During expiration, the increased pleural pressure compresses the airway causing a decrease in the airway size at the site of the intrathoracic obstruction.

Both inspiratory and expiratory stridor occur because of bacterial tracheitis and foreign bodies.

Laryngeal webs and vocal cord paralysis occur due to a fixed airway obstruction, which does not change with respiration.

Stridor symptoms

The most common presenting symptom of stridor is loud, raspy, noisy breathing. The caretaker may interpret this symptom as wheezing or even as a severe upper respiratory tract infection. A thorough history may provide helpful clues to the underlying cause of stridor 20. Depending on the underlying cause, the presentation may be acute or chronic and may be accompanied by other symptoms. If symptoms are not observed in the office, especially when they are present only at night, having parents make a tape recording, preferably even videotaping, can provide useful information.

- Hives: Should prompt evaluation for anaphylaxis secondary to allergic trigger

- A cough: Typically presents with croup

- Drooling: Typically seen with retropharyngeal abscess and epiglottitis, or foreign body aspiration

Stridor diagnosis

Initial evaluation should begin with a rapid assessment of the patient’s airway and effort of breathing. First, your doctor will ensure that the airways are patent and can move air in and out of the lungs. Your doctor will asses your rate and depth of breathing, and evaluate for hypoxia or cyanosis and if the patient looks like they are decompensating secondary to fatigue.

Physical Exam

- General appearance: Assess for any swelling of soft tissues of the neck and oropharynx, and rashes or hives, or any clubbing of digits.

- Assess tongue size, pharyngeal edema, or peritonsillar abscess. Be cautious in manipulating the oropharynx of a suspected epiglottitis patient, and consider doing this in a controlled setting such as the operating room.

- Lungs: Asses rate and depth of breathing, auscultate for inspiratory and expiratory stridor. Auscultate over the anterior neck to best hear stridor 4.

If the patient is hemodynamic stable with stridor, obtain a thorough history of present illness, review of systems, and medical history. Keys to the correct diagnosis can be delineated based on patient age, acuity of onset, history of exposures to allergens or infectious sources. In the stable patient with stridor, additional testing including imaging, radiography, and endoscopy may be performed.

In the patient is unstable, there may be signs of respiratory distress, gasping, drooling, fatigue, cyanosis, and these signs prompt a more rapid evaluation and rapid management to ensure airway patency. This can include endotracheal intubation or emergency surgical airway.

Laboratory testing may include a complete blood count (CBC), if an infectious source is suspected, however, this is usually not necessary for diagnosis. A rapid viral panel may be obtained to assess for parainfluenza viruses in the pediatric patient.

Sputum culture. A sample of the material (sputum) that is coughed up from the lungs is sent to the lab to check for infection.

Radiography including a lateral plain film may be obtained to assess for the size of the retropharyngeal space, in which a widened space may indicate a retropharyngeal abscess. A mnemonic can be used “6 at C2, and 22 at C6” to remember that the normal retropharyngeal space should not be greater than 6 mm at the level of C2 and not more than 22 mm at the level of C6. This view may also aid in visualizing of an enlarged epiglottis. An anteroposterior view to assessing for subglottic narrowing such as the “steeple” sign in croup. A chest radiograph can be obtained in suspected foreign body aspiration. However, a negative chest radiograph does not rule this out 21.

Imaging studies:

- AP and lateral radiographs of the neck may be useful in assessing for size of the epiglottis, retropharyngeal profile, and defining general tracheal anatomy.

- AP and lateral radiographs of the chest may identify radio-opaque foreign bodies.

- Inspiratory and expiratory films may be useful in demonstrating air-trapping due to airway obstruction.

- A positive exam will reveal hyperlucency of the obstructed lobe during expiration compared to inhalation due to air-trapping.

- May also see a shift of the mediastinum to the side opposite the obstruction.

Computed tomography (CT) can be considered when there is diagnostic uncertainty in the stable patient with stridor. CT of the chest and neck can evaluate for an infectious source such as cellulitis as well as stenotic lesions, or foreign bodies. Magnetic resonance imaging (MRI) can help discern tracheal stenosis in pediatric patients.

Laryngoscopy and bronchoscopy can help visualize the airways to establish a definitive diagnosis. If the patient appears critically ill, then endotracheal intubation should be performed if the cause of stridor is thought to be from epiglottitis or bacterial tracheitis.

Stridor treatment

Management of stridor should be undertaken from the time of initial assessment in the critically ill-appearing patient. Definitive treatment of stridor involves treating the underlying disorder. In general, the following precautions should be maintained when managing/treating stridor 22.

- Avoid agitating child with stridor

- Monitor for rapid deterioration due to respiratory failure

- Avoid direct examination or manipulation of the pharynx (if epiglottitis is suspected). In such situations, securing the airway takes precedence over diagnostic evaluation.

- Skilled personnel in airway management should accompany the patient at all times. Further evaluation should be performed where definitive airway management can be achieved in a controlled environment such as the operating room.

- Consider foreign body aspirations if symptoms develop acutely such as sudden coughing and choking in a previously healthy child.

- Avoid beta-agonists in croup; they are a possible risk of worsening upper airway obstruction.

As a temporizing measure in patients with severe distress, a mixture of helium and oxygen (heliox) improves airflow and reduces stridor in disorders of the large airways, such as postextubation laryngeal edema, croup, and laryngeal tumors. The mechanism of action is thought to be reduced flow turbulence as a result of lower density of helium compared with oxygen and nitrogen.

Nebulized racemic epinephrine (0.5 to 0.75 mL of 2.25% racemic epinephrine added to 2.5 to 3 mL of normal saline) and dexamethasone (10 mg IV, then 4 mg IV every 6 hours) may be helpful in patients in whom airway edema is the cause.

Endotracheal intubation should be used to secure the airway in patients with advanced respiratory distress, impending loss of airway, or decreased level of consciousness. When significant edema is present, endotracheal intubation can be difficult, and emergency surgical airway measures (eg, cricothyrotomy, tracheostomy) may be required.

Summary

Given that the cause of stridor is a robust, effective diagnosis and management of stridor relies on the clinical suspicion of the healthcare team, along with imaging modalities in unclear cases. Appropriate treatment then becomes directed toward the underlying cause and disease process. When a patient is presenting in extremis with stridor, it is up to the healthcare provider to rapidly recognize impending deterioration, gather the appropriate resources which many include rapid consultation with anesthesiology and appropriate surgical teams. In terms of croup, for instance, there have been many clinical trials demonstrating appropriate management based on the clinical presentation and clinical severity scores, which have led to decreased endotracheal intubations, as well as decreased hospital course length of stay, with the use of corticosteroids 23. When the cause of stridor is in question, it is crucial to communicate effectively, and as quickly as possible with the entire healthcare team including nurses, pharmacists, and surgical staff to ensure proper management and provide the appropriate treatment for each patient.

References- Sicari V, Zabbo CP. Stridor. [Updated 2018 Oct 27]. In: StatPearls [Internet]. Treasure Island (FL): StatPearls Publishing; 2018 Jan-. Available from: https://www.ncbi.nlm.nih.gov/books/NBK525995

- Stridor in infants and children. Schoem SR, Darrow DH, eds. Pediatric Otolaryngology. Itasca, IL: American Academy of Pediatrics; 2012. 323-52.

- Pfleger A, Eber E. Assessment and causes of stridor. Paediatr Respir Rev. 2016 Mar;18:64-72.

- Zochios V, Protopapas AD, Valchanov K. Stridor in adult patients presenting from the community: An alarming clinical sign. J Intensive Care Soc. 2015 Aug;16(3):272-273.

- Patel PH, Sharma S. Wheezing. [Updated 2018 Oct 27]. In: StatPearls [Internet]. Treasure Island (FL): StatPearls Publishing; 2018 Jan-. Available from: https://www.ncbi.nlm.nih.gov/books/NBK482454

- Martinez FD, Wright AL, Taussig LM, Holberg CJ, Halonen M, Morgan WJ. Asthma and wheezing in the first six years of life. The Group Health Medical Associates. N Engl J Med. 1995;332(3):133–138.

- The Diagnosis of Wheezing in Children. Am Fam Physician. 2008 Apr 15;77(8):1109-1114. https://www.aafp.org/afp/2008/0415/p1109.html

- Holinger, LD. Etiology of stridor in the neonate, infant and child. Ann Otol Rhinol Laryngol. 1980

- Diagnosis of Stridor in Children. Am Fam Physician. 1999 Nov 15;60(8):2289-2296. https://www.aafp.org/afp/1999/1115/p2289.html

- Lalakea Ml, Messner AH. Retropharyngeal abscess management in children: current practices. Otolaryngol Head Neck Surg. 1999 Oct. 121 (4):398-405.

- Mancuso RF. Stridor in neonates. Pediatr Clin North Am. 1996 Dec. 43 (6):1339-56.

- Ambrosio A, Brigger MT. Pediatric supraglottoplasty. Adv Otorhinolaryngol. 2012. 73:101-4.

- Digoy GP, Burge SD. Laryngomalacia in the older child: clinical presentations and management. Curr Opin Otolaryngol Head Neck Surg. 2014 Dec. 22 (6):501-5.

- Amir M, Youssef T. Congenital glottic web: management and anatomical observation. Clin Respir J. 2010 Oct. 4 (4):202-7.

- Klassen TP. Croup. A current perspective. Pediatr Clin North Am. 1999 Dec. 46 (6):1167-78.

- Bent J. Pediatric laryngotracheal obstruction: current perspectives on stridor. Laryngoscope. 2006 Jul. 116 (7):1059-70.

- Denoyelle F, Garabédian EN. Propranolol may become first-line treatment in obstructive subglottic infantile hemangiomas. Otolaryngol Head Neck Surg. 2010 Mar. 142 (3):463-4.

- Mikolajczak S, Quante G, Weissenborn S, Wafaisade A, Wieland U, Lüers JC, et al. The impact of cidofovir treatment on viral loads in adult recurrent respiratory papillomatosis. Eur Arch Otorhinolaryngol. 2012 Dec. 269 (12):2543-8.

- Zoumalan R, Maddalozzo J, Holinger LD. Etiology of stridor in infants. Ann. Otol. Rhinol. Laryngol. 2007 May;116(5):329-34.

- Pryor MP. Noisy breathing in children: history and presentation hold many clues to the cause. Postgrad Med. 1997 Feb. 101 (2):103-12.

- Marchese A, Langhan ML. Management of airway obstruction and stridor in pediatric patients. Pediatr Emerg Med Pract. 2017 Nov;14(11):1-24.

- Goodman TR, McHugh K. The role of radiology in the evaluation of stridor. Arch. Dis. Child. 1999 Nov;81(5):456-9.

- Sasidaran K, Bansal A, Singhi S. Acute upper airway obstruction. Indian J Pediatr. 2011 Oct;78(10):1256-61.