Supraspinatus tendinosis

Supraspinatus tendinosis refers to the intratendinous degeneration of the supraspinatus tendon that is thought to be a result of chronic overuse and that does not have a significant inflammatory component 1. Supraspinatus tendinosis and tendon tears is mostly between the fifth to sixth decades of life with the size of the tear increasing with age 2.

Shoulder anatomy

Your shoulder is made up of three bones: your upper arm bone (humerus), your shoulder blade (scapula), and your collarbone (clavicle). The shoulder is a ball-and-socket joint: the ball, or head, of your upper arm bone fits into a shallow socket in your shoulder blade. Your arm is kept in your shoulder socket by your rotator cuff. The rotator cuff is a group of four muscles that come together as tendons to form a covering around the head of the humerus. The rotator cuff attaches the humerus to the shoulder blade and helps to lift and rotate your arm. There is a lubricating sac called a bursa between the rotator cuff and the bone on top of your shoulder (acromion). The bursa allows the rotator cuff tendons to glide freely when you move your arm. When the rotator cuff tendons are injured or damaged, this bursa can also become inflamed and painful.

The key ligaments are the glenohumeral ligaments (inferior, middle, superior), which are thickened regions of the joint capsule, of which the inferior glenohumeral ligament is most important. Their role is to help stabilize the glenohumeral joint, in support of the rotator cuff muscles.

The key muscle group of the shoulder is the rotator cuff, made up of (from anterior to posterior) the subscapularis, supraspinatus, infraspinatus, and teres minor. The primary role of the rotator cuff is to function as the dynamic and functional stabilizer of the glenohumeral joint. The long head of the biceps tendon, located between the subscapularis and supraspinatus, also assists the rotator cuff in stabilizing the glenohumeral joint. These muscles and their tendons can be overused and injured in shoulder dominant activities such as swimming, with the most commonly injured portion of the cuff being the supraspinatus. On the other hand, the “power muscles” of the shoulders, including the latissimus dorsi, pectoralis, and deltoid, are responsible for moving the arm through space or water, but only infrequently sustain significant injury.

The supraspinatus arises from the medial two-thirds of supraspinatus fossa of the scapula, passes above the glenohumeral joint and inserts into the superior and middle impression of the greater tuberosity of the humerus 3. It acts as the upper stabilizer of the joint.

Supraspinatus muscle

- Abducts (primarily) and externally rotates the arm

- Important for the initial 0 to 15 degrees of shoulder abduction motion when the arm is adducted against the side of the trunk

- Beyond 15 degrees of abdduction, the deltoid moment arm acts synergistically to assist in shoulder/arm abduction

- Along with the other rotator cuff muscles provides dynamic stabilization of the shoulder

Finally, the trapezius, levator scapulae, rhomboids, and serratus anterior muscles stabilize and position the scapula and shoulder girdle, and are therefore very important to the swimming stroke. Without a stable platform from which to work, the shoulder and arm cannot function efficiently. Fortunately, they also are only occasionally the source of significant injury in the swimmer.

Figure 1. Shoulder anatomy

Supraspinatus tendinosis causes

The cause of supraspinatus tendinosis is not fully understood. Scientists theorize that an insult causing damage and acute inflammation sets the process in motion. The insult can be mechanical stressors, repetitive overloading, or toxic chemicals. Multifactorial confounding variables including age, genetic predisposition, and/or comorbidities, make one more prone to failure of healing that causes tendinosis 4.

Age is the most common factor for rotator cuff disease. It is a degenerative process that is progressive 5. Smoking is a known risk factor. A systematic review demonstrated increased rates and sizes of degenerative tears along with symptomatic tears seen in smokers; this has the potential to increase the number of surgeries 6. Another risk factor is a family history. In a study of rotator cuff disease in those under 40 years of age, there was a significant correlation between individuals with rotator cuff disease up to third cousins 6. Interestingly, poor posture has also been shown to be a predictor of rotator cuff disease. Tears were present in 65.8% patients with kyphotic-lordotic postures, 54.3% with flat-back postures, and 48.9% with sway-back postures; tears were present in only 2.9% of patients with ideal alignment 6. Other risk factors include trauma, hypercholesterolemia, and occupations or activities requiring significant overhead activity 7.

Partial tears are at risk for further propagation. These risk factors include: tear size, symptoms, location, and age. Tear size: A small tear may remain dormant, while larger tears are more likely to undergo structural deterioration. The critical size for sending a small tear towards a larger or complete tear has yet to be defined 8. Tear propagation correlates with symptom development. Actively enlarging tears have a five times higher likelihood of developing symptoms than those tears that remain the same size 8. The location of the tear also influences progression. Anterior tears are more likely to progress to cuff degeneration 8. Finally, age is a risk factor. Patients over age 60 are more likely to develop tears that progress. Younger patients with full-thickness tears appear more capable of adapting to stress and tear propagation than those 60 years of age and older 8.

Risk factors for supraspinatus tendinosis

- Age

- Repetitive Overhead Activities

- Shape of a shoulder bone called the ‘acromion’

Supraspinatus tendinosis prevention

Primary prevention should be considered an integral part in the treatment of supraspinatus tendinosis. Education of patients at risk can do much to circumvent the development of supraspinatus tendinosis. Athletes, particularly those involved in throwing and overhead sports, and laborers with repetitive shoulder stress should be instructed in proper warm-up techniques, specific strengthening techniques, and have a good understanding of the warning signs of early tendinosis.

Supraspinatus tendinosis stages

In 1972, Neer 9 first introduced the concept of rotator cuff impingement to the literature, stating that it results from mechanical impingement of the rotator cuff tendon beneath the anteroinferior portion of the acromion, especially when the shoulder is placed in the forward-flexed and internally rotated position.

Neer describes the following 3 stages in the spectrum of rotator cuff impingement:

- Stage 1, commonly affecting patients younger than 25 years, is depicted by acute inflammation, edema, and hemorrhage in the rotator cuff. This stage usually is reversible with nonoperative treatment.

- Stage 2 usually affects patients aged 25-40 years, resulting as a continuum of stage 1. The rotator cuff tendon progresses to fibrosis and tendonitis, which commonly does not respond to conservative treatment and requires operative intervention.

- Stage 3 commonly affects patients older than 40 years. As this condition progresses, it may lead to mechanical disruption of the rotator cuff tendon and to changes in the coracoacromial arch with osteophytosis along the anterior acromion. Surgical l anterior acromioplasty and rotator cuff repair is commonly required.

In all Neer stages, the cause is impingement of the rotator cuff tendons under the acromion and a rigid coracoacromial arch, eventually leading to degeneration and tearing of the rotator cuff tendon.

Although rotator cuff tears are more common in the older population, impingement and rotator cuff disease are frequently seen in the repetitive overhead athlete. The increased forces and repetitive overhead motions can cause attritional changes in the distal part of the rotator cuff tendon, which is at risk due to poor blood supply. Impingement syndrome and rotator cuff disease affect athletes at a younger age compared with the general population.

Magnetic resonance imaging (MRI) is considered the imaging study of choice for evaluation of shoulder pathology. In general, conservative measures for shoulder impingement syndrome are applied for at least 3-6 months or longer if the individual is improving, which is usually the case in 60-90% of patients. If the patient remains significantly disabled and has no improvement after 3 months of conservative treatment, the clinician must seek further diagnostic work-up, as well as reconsider other etiologies or refer the person for surgical evaluation.

Supraspinatus tendinosis symptoms

Supraspinatus tendinosis pain commonly causes local swelling and tenderness in the front of the shoulder. You may have pain and stiffness when you lift your arm. There may also be pain when the arm is lowered from an elevated position.

Beginning symptoms may be mild. Patients frequently do not seek treatment at an early stage. These symptoms may include:

- Minor pain that is present both with activity and at rest

- Pain radiating from the front of the shoulder to the side of the arm

- Sudden pain with lifting and reaching movements

- Athletes in overhead sports may have pain when throwing or serving a tennis ball

As the problem progresses, the symptoms increase:

- Pain while sleeping at night

- Loss of strength and motion

- Difficulty doing activities that place the arm behind the back, such as buttoning or zippering

If the pain comes on suddenly, the shoulder may be severely tender. All movement may be limited and painful.

You may have pain in the shoulder when you lift your arm, or pain that moves down your arm. At first, the pain may be mild and only present when lifting your arm over your head, such as reaching into a cupboard. Over-the-counter medication, such as aspirin or ibuprofen, may relieve the pain at first.

Over time, the pain may become more noticeable at rest, and no longer goes away with medications. You may have pain when you lie on the painful side at night. The pain and weakness in the shoulder may make routine activities such as combing your hair or reaching behind your back more difficult.

Supraspinatus tendinosis complications

Supraspinatus tendinosis pain can take a long time to get better. It can also progress to tears of your rotator cuff tendons, perhaps leading to long term permanent weakness. Other complications may include progression to adhesive capsulitis, cuff tear arthropathy, and reflex sympathetic dystrophy. Complications also may result from surgery, injection, physical therapy, or medication.

Supraspinatus tendinosis diagnosis

After discussing your symptoms and medical history, your doctor will examine your shoulder. He or she will check to see whether it is tender in any area or whether there is a deformity. To measure the range of motion of your shoulder, your doctor will have you move your arm in several different directions. He or she will also test your arm strength.

Your doctor will check for other problems with your shoulder joint. He or she may also examine your neck to make sure that the pain is not coming from a “pinched nerve,” and to rule out other conditions, such as arthritis.

Specifically, rotator cuff strength and/or pathology can be assessed via the following examinations:

Supraspinatus

- Jobe’s test: a positive test is pain/weakness with resisted downward pressure while the patient’s shoulder is at 90 degrees of forward flexion and abduction in the scapular plane with the thumb pointing toward the floor.

- Drop arm test: the patient’s shoulder is brought into a position of 90 degrees of shoulder abduction in the scapular plane. The examiner initially supports the limb and then instructs the patient to slowly adduct the arm to the side of the body. A positive test includes the patient’s inability to maintain the abducted position of the shoulder and/or an inability to adduct the arm to the side of the trunk in a controlled manner.

Imaging tests

Other tests which may help your doctor confirm your diagnosis include:

- X-rays. The first imaging tests performed are usually x-rays. Because x-rays do not show the soft tissues of your shoulder like the rotator cuff, plain x-rays of a shoulder with rotator cuff pain are usually normal or may show a small bone spur.

- Magnetic resonance imaging (MRI) or ultrasound. These studies can better show soft tissues like the rotator cuff tendons. They can show the rotator cuff tear, as well as where the tear is located within the tendon and the size of the tear. An MRI can also give your doctor a better idea of how “old” or “new” a tear is because it can show the quality of the rotator cuff muscles.

Supraspinatus tendinosis treatment

If you have supraspinatus tendinosis and you keep using it despite increasing pain, you may cause further damage. The goal of any treatment is to reduce pain and restore function. There are several treatment options for supraspinatus tendinosis and the best option is different for every person. In planning your treatment, your doctor will consider your age, activity level and general health.

Supraspinatus tendinosis treatment options may include:

- Rest. Your doctor may suggest rest and limiting overhead activities. He or she may also prescribe a sling to help protect your shoulder and keep it still.

- Activity modification. Avoid activities that cause shoulder pain.

- Nonsteroidal anti-inflammatory medication (NSAIDs). Drugs like ibuprofen and naproxen reduce pain and swelling.

- Strengthening exercises and physical therapy. Specific exercises will restore movement and strengthen your shoulder. Your exercise program will include stretches to improve flexibility and range of motion. Strengthening the muscles that support your shoulder can relieve pain and prevent further injury.

- Steroid injection. If rest, medications, and physical therapy do not relieve your pain, an injection of a local anesthetic and a cortisone preparation may be helpful. Cortisone is a very effective anti-inflammatory medicine; however, it is not effective for all patients.

Supraspinatus tendinosis physical therapy

Physical therapy or physiotherapy is an essential part of the treatment of supraspinatus tendinosis. Your physiotherapist will help you strengthen the muscles of the rotator cuff, advise you movements to avoid and help you regain your flexibility.

If the pain persists or if movement is not possible because of severe pain, a steroid injection may reduce pain and inflammation enough to allow effective physiotherapy.

A physical therapist can teach you range-of-motion exercises to help recover as much mobility in your shoulder as possible. Your commitment to doing these exercises is important to optimize recovery of your mobility.

Specific exercises will help restore motion. These may be under the supervision of a physical therapist or via a home program. Therapy includes stretching or range of motion exercises for the shoulder. Sometimes heat is used to help loosen the shoulder up before the stretching exercises.. Below are examples of some of the exercises that might be recommended.

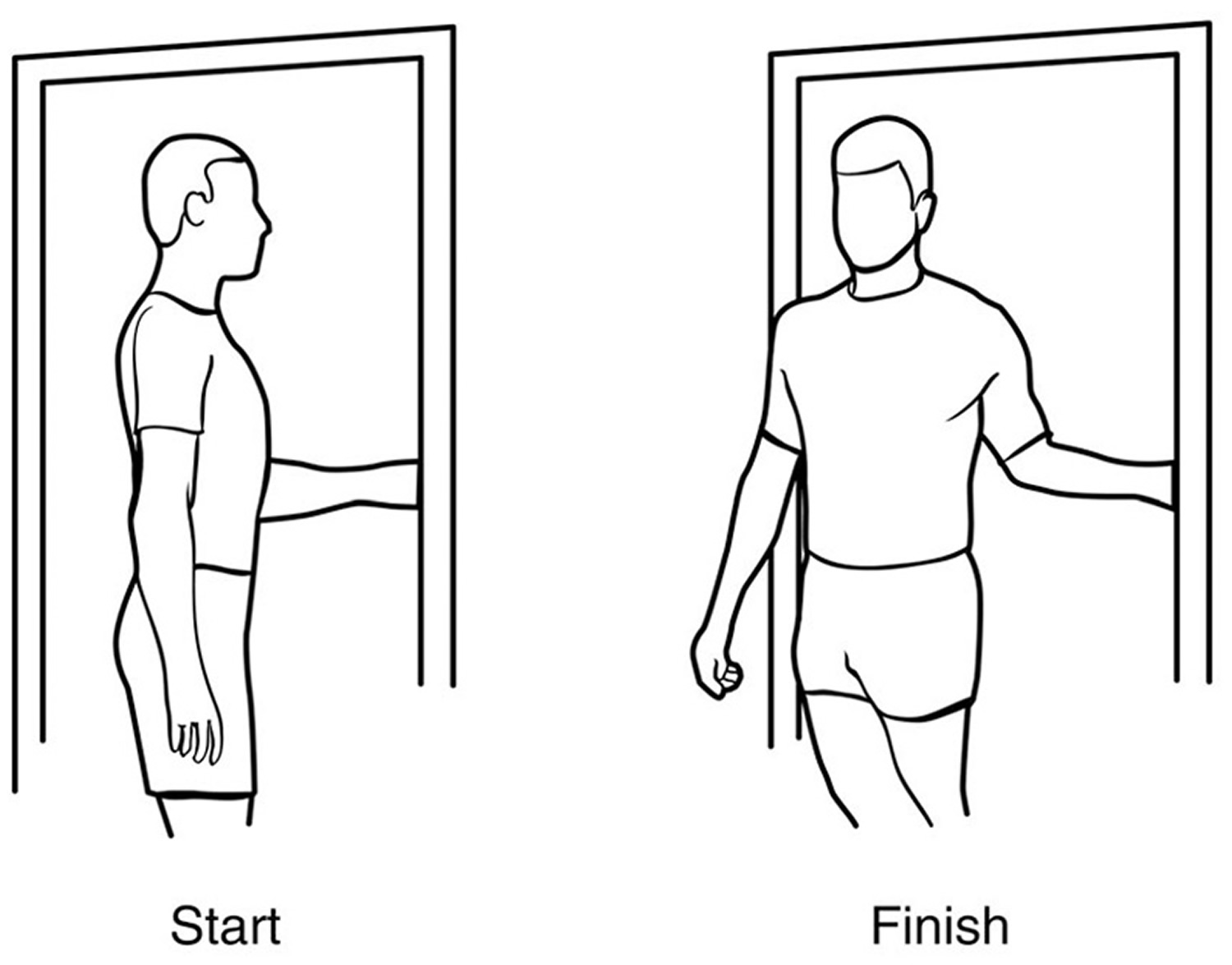

External rotation — passive stretch

Stand in a doorway and bend your affected arm 90 degrees to reach the doorjamb. Keep your hand in place and rotate your body as shown in the illustration (Figure 2). Hold for 30 seconds. Relax and repeat.

Figure 2. Supraspinatus tendinosis exercise – external rotation passive stretch

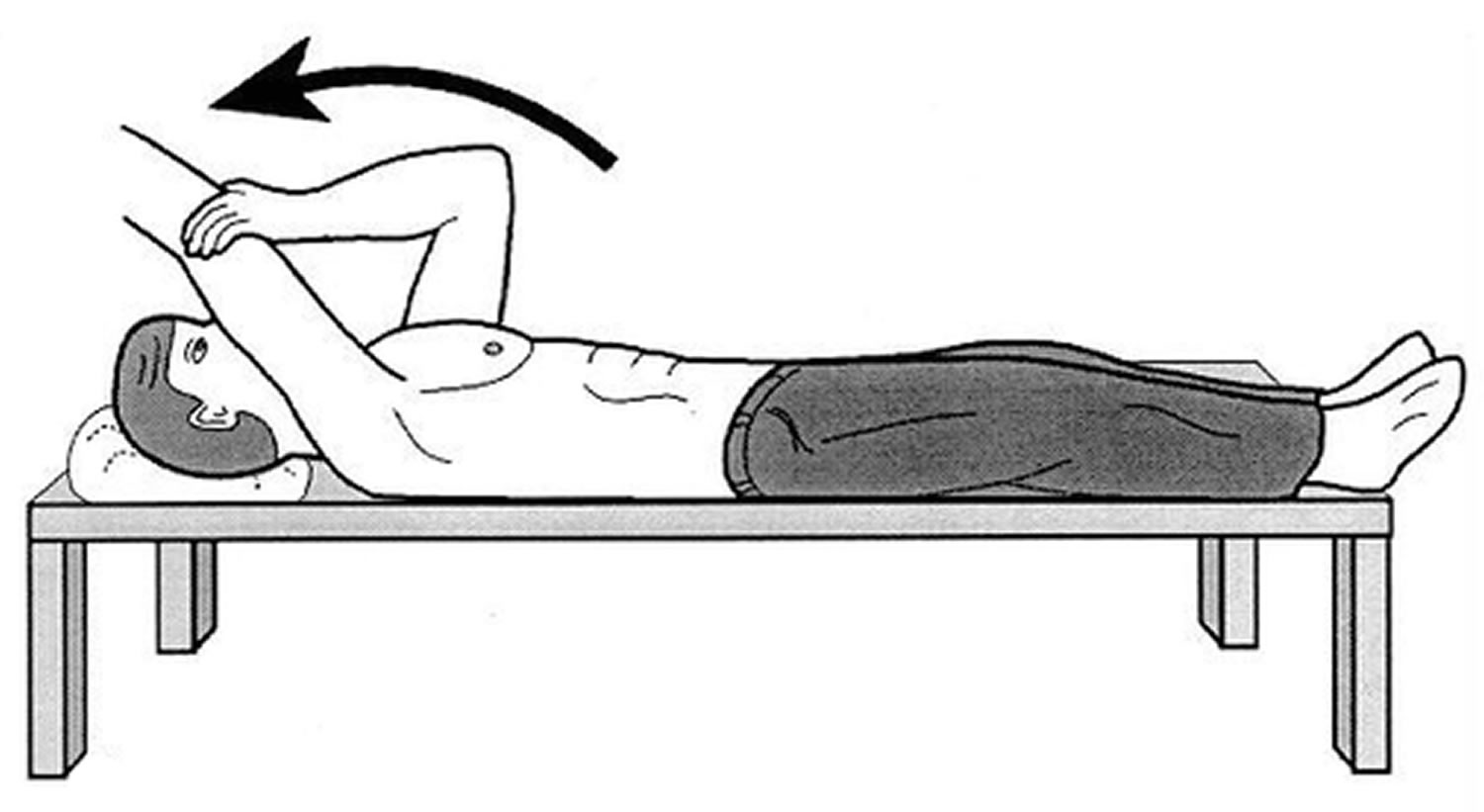

Forward flexion — supine position

Lie on your back with your legs straight. Use your unaffected arm to lift your affected arm overhead until you feel a gentle stretch. Hold for 15 seconds and slowly lower to start position. Relax and repeat.

Figure 3. Supraspinatus tendinosis exercise – forward flexion in supine position

Crossover arm stretch

Gently pull one arm across your chest just below your chin as far as possible without causing pain. Hold for 30 seconds. Relax and repeat.

Figure 4. Supraspinatus tendinosis exercise – crossover arm stretch

Surgical treatment

When nonsurgical treatment does not relieve pain, your doctor may recommend surgery.

The goal of surgery is to create more space for the rotator cuff. To do this, your doctor will remove the inflamed portion of the bursa. He or she may also perform an anterior acromioplasty, in which part of the acromion is removed. This is also known as a subacromial decompression. These procedures can be performed using either an arthroscopic or open technique.

Arthroscopic technique

In arthroscopy, thin surgical instruments are inserted into two or three small puncture wounds around your shoulder. Your doctor examines your shoulder through a fiberoptic scope connected to a television camera. He or she guides the small instruments using a video monitor, and removes bone and soft tissue. In most cases, the front edge of the acromion is removed along with some of the bursal tissue.

Your surgeon may also treat other conditions present in the shoulder at the time of surgery. These can include arthritis between the clavicle (collarbone) and the acromion (acromioclavicular arthritis), inflammation of the biceps tendon (biceps tendonitis), or a partial rotator cuff tear.

Open surgical technique

In open surgery, your doctor will make a small incision in the front of your shoulder. This allows your doctor to see the acromion and rotator cuff directly.

Rehabilitation

After surgery, your arm may be placed in a sling for a short period of time. This allows for early healing. As soon as your comfort allows, your doctor will remove the sling to begin exercise and use of the arm.

Your doctor will provide a rehabilitation program based on your needs and the findings at surgery. This will include exercises to regain range of motion of the shoulder and strength of the arm. It typically takes 2 to 4 months to achieve complete relief of pain, but it may take up to a year.

Return to play

Return to play is restricted until full pain-free range of motion (ROM) is restored, both rest and activity-related pain are eliminated, and provocative impingement signs are negative. Isokinetic strength testing must be 90% compared to the contralateral side. When the patient is symptom-free, resuming activities is gradual, first during practice to build up endurance while working on modified techniques/mechanics, and then in simulated game situations. The athlete should continue flexibility and strengthening exercises after returning to his/her sport to prevent recurrence.

Shoulder impingement prognosis

In general, prognosis for prompt and correct diagnosis and treatment of supraspinatus tendinosis is good and 60-90% of patients improve and are symptom-free with conservative treatment. Surgical outcomes are promising in patients who fail conservative therapy.

References- Aicale R, Tarantino D, Maffulli N. Overuse injuries in sport: a comprehensive overview. J Orthop Surg Res. 2018 Dec 05;13(1):309.

- Calcific tendinitis of the shoulder. Speed CA, Hazleman BL. N Engl J Med. 1999 May 20; 340(20):1582-4.

- Maruvada S, Varacallo M. Anatomy, Rotator Cuff. [Updated 2018 Nov 14]. In: StatPearls [Internet]. Treasure Island (FL): StatPearls Publishing; 2019 Jan-. Available from: https://www.ncbi.nlm.nih.gov/books/NBK441844

- Santana JA, Sherman Al. Jumpers Knee. [Updated 2019 Apr 2]. In: StatPearls [Internet]. Treasure Island (FL): StatPearls Publishing; 2019 Jan-. Available from: https://www.ncbi.nlm.nih.gov/books/NBK532969

- Dang A, Davies M. Rotator Cuff Disease: Treatment Options and Considerations. Sports Med Arthrosc Rev. 2018 Sep;26(3):129-133.

- Sambandam SN, Khanna V, Gul A, Mounasamy V. Rotator cuff tears: An evidence based approach. World J Orthop. 2015 Dec 18;6(11):902-18.

- Moulton SG, Greenspoon JA, Millett PJ, Petri M. Risk Factors, Pathobiomechanics and Physical Examination of Rotator Cuff Tears. Open Orthop J. 2016;10:277-285.

- Schmidt CC, Morrey BF. Management of full-thickness rotator cuff tears: appropriate use criteria. J Shoulder Elbow Surg. 2015 Dec;24(12):1860-7.

- Neer CS 2nd. Anterior acromioplasty for the chronic impingement syndrome in the shoulder: a preliminary report. J Bone Joint Surg Am. 1972 Jan. 54(1):41-50.