What is tarsal coalition

Tarsal coalition is an abnormal bony, cartilaginous or fibrous connection between two or more tarsal bones in your foot 1. The tarsal bones are located toward the back of the foot and in the heel, and the connection of the bones can result in a severe, rigid flatfoot. The most common types of tarsal coalition occur in the talocalcaneal joint and calcaneonavicular joint 2. Although tarsal coalition is often present at birth, children typically do not show signs of the disorder until early adolescence. The foot may become stiff and painful, and everyday physical activities are often difficult. Tarsal coalition is an often unrecognised cause of foot and ankle pain 3. For many children with tarsal coalition, symptoms are relieved with simple treatments, such as orthotics and physical therapy. If a child has severe symptoms that do not respond to simple treatments and continue to interfere with their daily activities, surgery may be recommended.

Foot anatomy

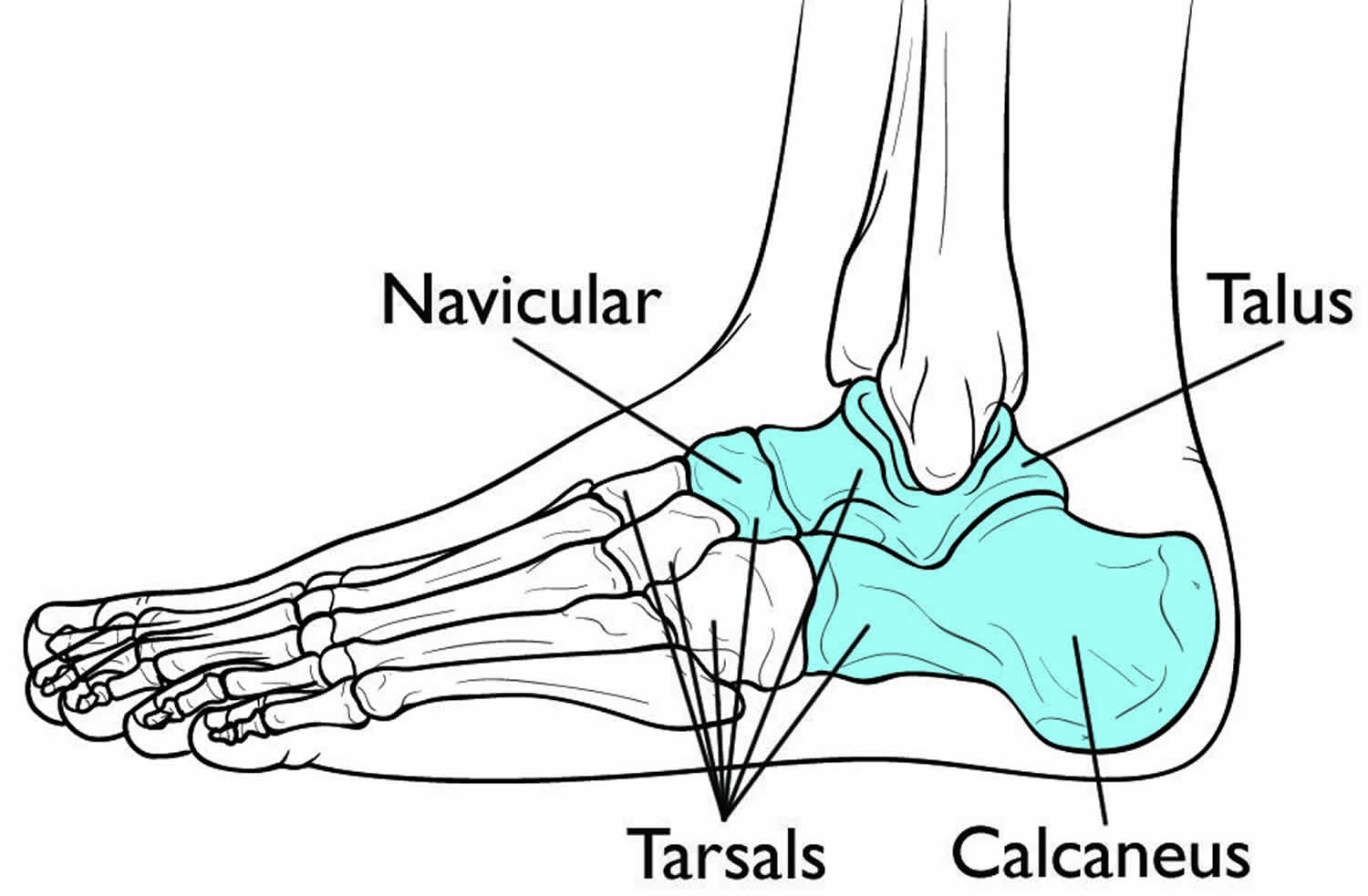

The bones of the feet are commonly divided into three parts: the hindfoot, midfoot, and forefoot. Seven bones — called tarsals — compose the hindfoot and midfoot. Of these bones, the calcaneus, talus, and navicular are most commonly involved in tarsal coalition.

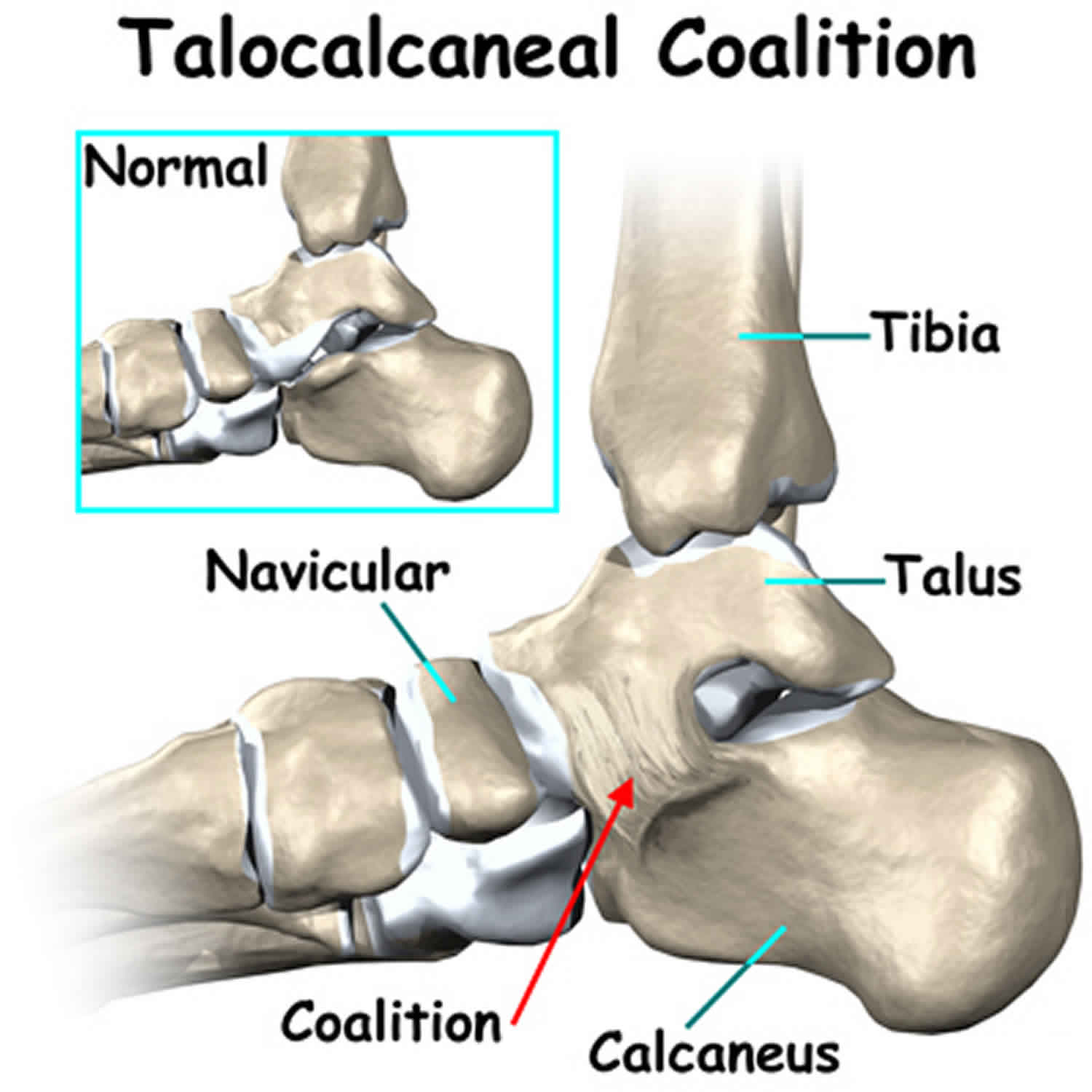

Figure 1. Tarsal bones anatomy (the calcaneus, talus, and navicular bones are those most often affected by tarsal coalition.)

Figure 3. Talocalcaneal coalition

Tarsal coalition causes

Most often, tarsal coalition occurs during fetal development, resulting in the individual bones not forming properly. Less common causes of tarsal coalition include infection, arthritis, or a previous injury to the area.

A tarsal coalition occurs when two bones grow into one another, connected by a bridge of bone, cartilage, or strong, fibrous tissue. These bridges are often referred to as “bars” and they can cover just a small amount of the joint space between the bones, or a large portion of the space.

The two most common sites of tarsal coalition are between the calcaneus and navicular bones, or between the talus and calcaneus bones. However, other joints can also be affected.

It is estimated that one out of every 100 people may have a tarsal coalition. In about 50% of cases, both feet are affected. The exact incidence of the disorder is hard to determine because many coalitions never cause noticeable symptoms.

In most people, the condition begins before birth. It is caused by a gene mutation that affects the cells that produce the tarsal bones. Although the coalition forms before birth, its presence is often not discovered until late childhood or adolescence.

This is because babies’ feet contain a higher percentage of soft, growing cartilage. As a child grows, this cartilage mineralizes (ossifies), resulting in hard, mature bone. If a coalition exists, it may harden, too, and fuse the growing bones together with a solid bridge of bone or fibrous tissue similar to a scar. The ossification of the coalition typically happens between ages 8 and 16, depending upon which bones are involved. As a result, the hindfoot stiffens, causing pain and other symptoms.

The stiffness and stress that tarsal coalitions produce may lead to arthritis over time.

Tarsal coalition symptoms

Many tarsal coalitions are never discovered because they do not cause symptoms or any obvious foot deformity. While many people who have a tarsal coalition are born with this condition, the symptoms generally do not appear until the bones begin to mature, usually around ages 9 to 16. Sometimes there are no symptoms during childhood. However, pain and symptoms may develop later in life.

The symptoms of tarsal coalition may include one or more of the following:

- Pain (mild to severe) when walking or standing

- Tired or fatigued legs

- Muscle spasms in the leg, causing the foot to turn outward when walking

- Flatfoot (in one or both feet). A rigid, flat foot that makes it difficult to walk on uneven surfaces. To accommodate for the foot’s lack of motion, the patient may roll the ankle more than normal, which may result in recurrent ankle sprains.

- Walking with a limp

- Stiffness of the foot and ankle. The pain usually occurs below the ankle around the middle or back half of the foot.

- Increased pain or a limp with higher levels of activity.

Tarsal coalition diagnosis

A tarsal coalition is difficult to identify until a child’s bones begin to mature. It is sometimes not discovered until adulthood. Diagnosis includes obtaining information about the duration and development of the symptoms as well as a thorough examination of the foot and ankle. The findings of this examination will differ according to the severity and location of the coalition.

After discussing your symptoms and general health history, your doctor will do a complete examination of your foot and ankle, which will include checking your foot flexibility and gait. Patients with tarsal coalitions may have a flat arch that does not fully correct when pushing up on the toes and raising the heel.

In addition to examining the foot, the surgeon will order x-rays. Advanced imaging studies may also be required to fully evaluate the condition.

Imaging Tests

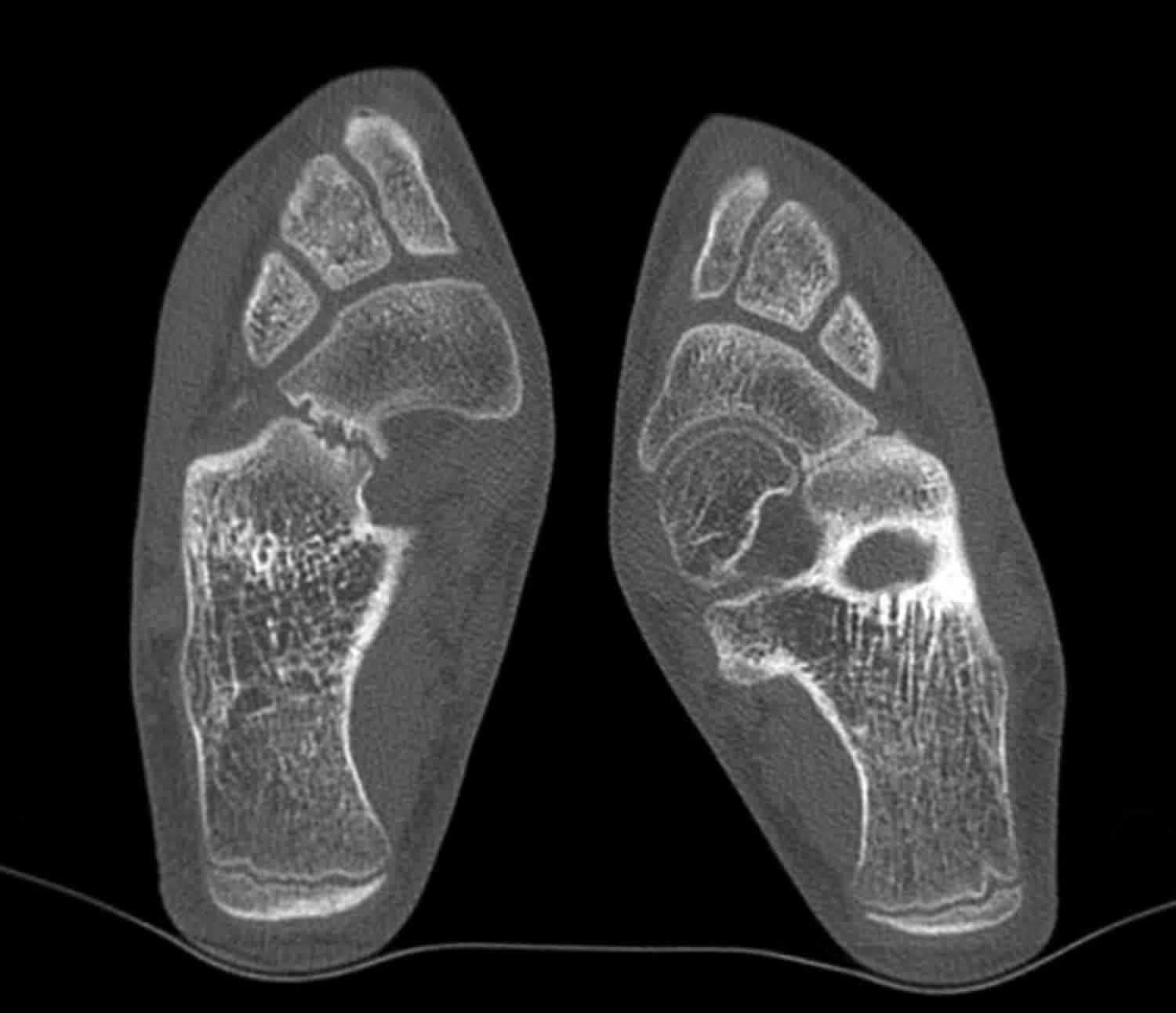

To accurately diagnose the number, location and extent of the coalition(s), your doctor will order images of your foot and ankle.

- X-rays. These tests provide clear images of bone. Many coalitions are visible on x-rays.

- Computed tomography (CT) scans. The images produced with computed tomography provide greater detail of the bones. CT scans are the gold standard for imaging tarsal coalitions because they can show more subtle bars that may be missed with plain x-rays.

- Magnetic resonance (MRI) scans. These imaging tests provide detailed pictures that include soft tissues. Your doctor may order this test to look for irregular bars formed from cartilage or fibrous tissue.

Tarsal coalition treatment

Tarsal coalitions only require treatment if they are causing symptoms.

Non-surgical treatment

The goal of non-surgical treatment of tarsal coalition is to relieve the symptoms and reduce the motion at the affected joint. One or more of the following options may be used, depending on the severity of the condition and the response to treatment:

- Rest. Taking a break from high-impact activity for a period time — 3 to 6 weeks — can reduce stress on the tarsal bones and relieve pain.

- Oral medications. Nonsteroidal anti-inflammatory drugs (NSAIDs), such as ibuprofen, may be helpful in reducing the pain and inflammation.

- Orthotic devices. Custom orthotic devices can be beneficial in distributing weight away from the joint, limiting motion at the joint and relieving pain. Arch supports, shoe inserts like heel cups and wedges, and other types of orthotics may be recommended to help stabilize the foot and relieve pain.

- Temporary boot or cast. These options can immobilize the foot and take stress off of the tarsal bones. The foot is placed in a cast or cast boot, and crutches are used to avoid placing weight on the foot.

- Injection of an anesthetic agent. Injection of an anesthetic into the leg may be used to relax spasms and is often performed prior to immobilization.

- Steroid injections. An injection of cortisone into the affected joint reduces the inflammation and pain. Sometimes more than one injection is necessary. Injections of steroid medications may be used in conjunction with other nonsurgical options to provide temporary pain relief.

- Physical therapy. Physical therapy may include massage, range-of-motion exercises, and ultrasound therapy.

Tarsal coalition surgery

If the patient’s symptoms are not adequately relieved with nonsurgical treatment, surgery is an option. The foot and ankle surgeon will determine the best surgical approach based the patient’s age, condition, arthritic changes, and activity level.

The surgical procedure your doctor recommends will depend on the size and location of the coalition, as well as whether the joints between the bones show signs of arthritis.

- Resection. In this procedure, the coalition is removed and replaced with muscle or fatty tissue from another area of the body. This is the most common surgery for tarsal coalition because it preserves normal foot motion and successfully relieves symptoms in most patients who do not have signs of arthritis.

- Fusion. Larger, more severe coalitions that cause significant deformity and also involve arthritis may be treated with joint fusion. The goal of fusion is to limit movement of painful joints and place the bones in the proper position. In fusion for tarsal coalition, the bones may be held in place with large screws, pins, or screw-and-plate devices.

Tarsal coalition surgery recovery

Depending upon the type and location of your surgery, a cast will be required for a period of time to protect the surgical site and prevent you from putting weight on the foot. Casts are typically replaced with walking boots, and your doctor may recommend physical therapy exercises to begin restoring range of motion and strength.

Your doctor will determine when it is safe for you to begin putting weight on your foot. Arch supports or orthotics may also be helpful in stabilizing the joint, even after surgery.

Although it may take several months to fully recover, most patients have pain relief and improved motion after surgery.

References- Klammer G, Espinosa N, Iselin LD. Coalitions of the Tarsal Bones. Foot Ankle Clin. 2018 Sep. 23 (3):435-449.

- Docquier PL, Maldaque P, Bouchard M. Tarsal coalition in paediatric patients. Orthop Traumatol Surg Res 2018. pii: S1877-0568(18)30095-1. doi: 10.1016/j.otsr.2018.01.019

- Wahnert D, Gruneweller N, Evers J, Sellmeier AC, Raschke MJ, Ochman S. An unusual cause of ankle pain: fracture of a talocalcaneal coalition as a differential diagnosis in an acute ankle sprain: a case report and literature review. BMC Musculoskelet Disord. 2013;14:111