Ureterocele

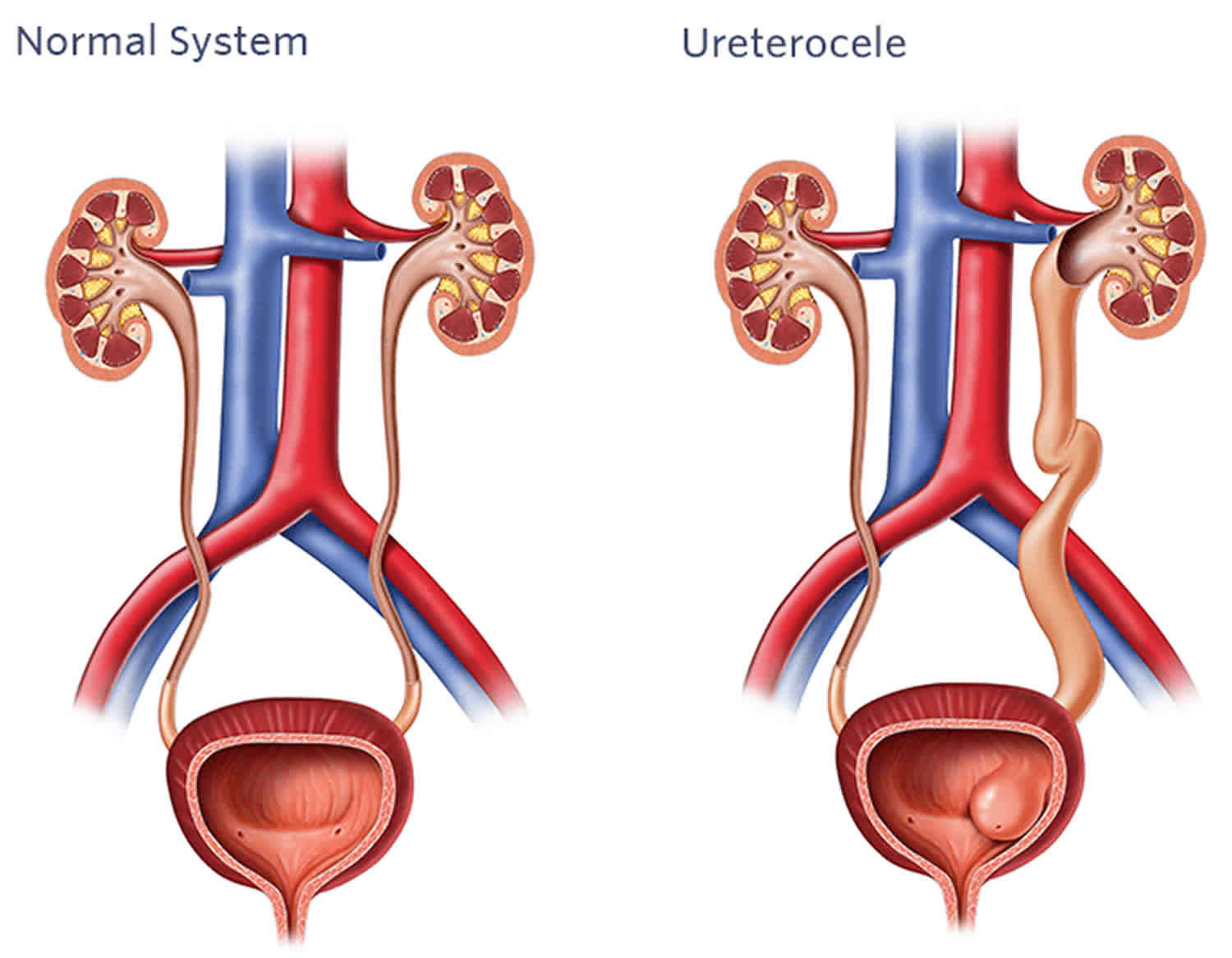

Ureterocele is a cystic out-pouching of the distal ureter into the urinary bladder resulting in obstruction of urine flow, dilation of the ureter and renal pelvis and loss of renal function 1. The swelling resembles a balloon on ultrasound or during a camera examination of the bladder. Ureteroceles in two ureters draining a kidney (duplex anomalies) can be associated with urine refluxing backward to the kidney through the second adjacent ureter. This reflux is related to weakness of the flap valve from having the ureter join the bladder in an abnormal location. Ureterocele is a congenital anomaly (present at birth) that affects girls more than boys 2. Ureterocele is one of the more challenging urologic anomalies facing pediatric and adult urologists. Ureteroceles may pose a diagnostic and therapeutic dilemma, with perplexing clinical symptoms resulting from a spectrum of abnormal embryogenesis associated with anomalous development of the intravesical ureter, the kidney, or the collecting system.

An ureterocele happens when the end of ureters that enters the bladder don’t develop properly. Ureterocele is considered to be a birth defect. The ureteral end swells like a balloon that may stop flow of urine to the bladder.

Ureteroceles occur in approximately 1 in every 4000 to 1 in 12,000 children and occur most commonly in Caucasian population 3. Females are affected 4-7 times more often than males. A slight left-sided preponderance appears to exist, and approximately 10% of ureteroceles are bilateral 4. Ureteroceles are most often found in children age 2 or younger. Sometimes it is found older children or adults. In the adult population, ureteroceles also occur more frequently in females. Orthotopic ureteroceles occur in 17-35% of cases, with an incidence of ectopic ureteroceles of approximately 80% in most pediatric series. Similarly, approximately 80% of ureteroceles are associated with the upper pole moiety of a duplex system. When ectopic ureteroceles are associated with duplicated collecting systems, the upper pole moiety may be dysplastic or poorly functioning. Single-system ectopic ureteroceles are uncommon and are most often found in males.

Ureteroceles can:

- Swell a lot, taking up most of the bladder; or swell only a small amount.

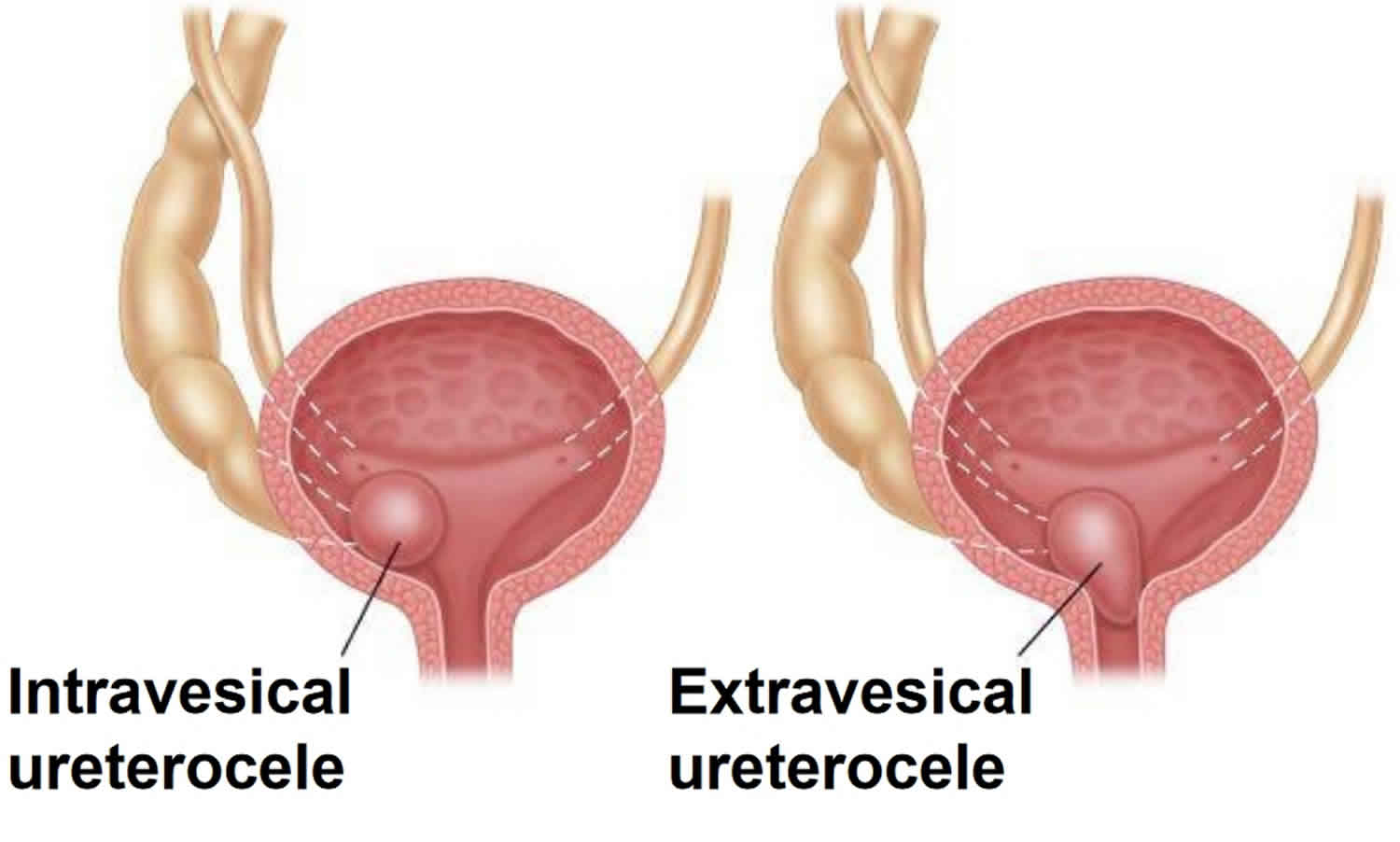

- Be inside the bladder (intravesical) or outside the bladder, through the bladder neck and urethra (ectopic or extravesical).

- Happen with a single ureter or a double ureter (duplex collecting system). In 90% of girls with an ureterocele, the problem is from this.

- Happen with or without Vesicoureteral reflux (VUR) (urine flowing back to the kidneys).

- Happen on both sides, from both kidneys (bilateral ureterocele).

Not all ureteroceles are the same:

- Ureteroceles vary in size; some are barely seen while others can take up most of the bladder.

- Ureteroceles can be inside the bladder (intravesical) or extend outside the bladder, through the bladder neck and urethra (ectopic or extravesical).

- The opening of the ureterocele into the bladder can be narrow (causing some degree of obstruction), normal in size or larger in size.

- Ureteroceles can be associated with a single system (one kidney and one ureter) or a duplex kidney (one kidney with two separate ureters).

- Ureteroceles can be associated with vesicoureteral reflux (VUR). VUR occurs when urine in the bladder flows back into one or both ureters and often back into the kidneys.

Ureteroceles may be categorized on the basis of their relationship with the renal unit or on distal ureteral configuration and location. The following are the different types of ureteroceles classified by their association with the renal unit:

- Single-system ureteroceles are those associated with a single kidney, collecting system, and ureter.

- Duplex-system ureteroceles are associated with kidneys that have completely duplicated ureters.

- Orthotopic (intravesical) ureterocele is a term used for a ureterocele contained within the bladder. An orthotopic ureterocele may prolapse into and beyond the bladder neck, but the origin of the walls of an orthotopic ureterocele are contained within the bladder. The orthotopic ureterocele usually arises from a single renal unit with one collecting system and is more commonly diagnosed in adults.

- Ectopic (extravesical) ureterocele refers to ureteroceles with tissue that originates at the bladder neck or beyond, into the urethra. They typically arise from the upper pole moiety of a duplicated collecting system and are more common in the pediatric population.

Keep in mind that not all single-system ureteroceles assume an orthotopic position and that not all duplex collecting system ureteroceles are positioned in an ectopic location.

Another method of classifying ureterocele is based on location and configuration. Stephens proposed a classification system based on the features of the affected ureteral orifice, as follows:

- Stenotic ureteroceles are located inside the bladder with an obstructing orifice.

- Sphincteric ureteroceles lie distal to the internal sphincter. The ureterocele orifice may be normal or patulous, but the distal ureter leading to it becomes obstructed by the activity of the internal sphincter.

- Sphincterostenotic ureteroceles have characteristics of both stenotic and sphincteric ureteroceles.

- Cecoureteroceles are elongated beyond the ureterocele orifice by tunneling under the trigone and the urethra.

At present, this classification is used infrequently 5. The characterization based on the location of the orifice (intravesical vs ectopic) is more commonly used because it has therapeutic implications, especially with respect to the likelihood of the presence of vesicoureteral reflux (VUR) following transurethral puncture of the ureterocele.

Ureteroceles may be asymptomatic or may produce a wide range of clinical signs and symptoms, from recurrent cystitis to bladder outlet obstruction to renal failure. Because of the obstructive nature of ureteroceles, the activity of the affected renal unit varies from a normal, well-functioning kidney to a nonfunctioning, dysplastic renal segment or kidney. However, with proper diagnosis and treatment, the outcome remains excellent.

Management of ureterocele remains both challenging and controversial, with its wide clinical spectrum making development of a standardized approach difficult. Robotic-assisted ureteral reimplantation and heminephrectomy are gaining popularity and will continue to evolve 6. Open ureteral reimplantation, ureteropyelostomy and heminephrectomy currently remain the criterion standard for surgical management of symptomatic ureteroceles that are not successfully managed endoscopically.

Although different surgical philosophies exist in managing adult and pediatric ureteroceles, the following principles may apply:

- Endoscopic puncture of ureteroceles should be used as a primary treatment modality in any patient with urosepsis or concurrent medical conditions that pose significant anesthesia-related risk.

- Upper pole heminephrectomy with partial ureterectomy is reasonable in the setting of a nonfunctioning upper pole renal moiety without associated vesicoureteral reflux.

- Ureterocelectomy and bladder reconstruction are acceptable in the setting of a ureterocele associated with significant vesicoureteral reflux in either kidney.

Figure 1. Ureterocele

My baby was diagnosed with an ureterocele on a prenatal ultrasound. She seems very healthy. Is it absolutely necessary for her to undergo treatment?

To prevent kidney damage and urinary tract infections (UTIs), treatment is often recommended. Sometimes, a “watch and wait” approach is used. It is important to continue observing your child to make sure the problem either self-corrects, or is surgically corrected.

My doctor has recommended that my daughter take antibiotics because she has an ureterocele and urinary reflux. Is it safe to take antibiotics every day?

Many children and adults take a low dose of an antibiotic every day to prevent urinary tract infections (UTIs). This form of therapy has been used for over 35 years. It has proven to be relatively safe, as long as the dose is small. It is important to weigh the risk of taking the antibiotic against the risk of a serious kidney infection.

My child was diagnosed with an ureterocele and it was punctured through a small scope. Now there is reflux into the ureterocele and the lower part of the kidney. Will more surgery be necessary?

In most cases, if there is reflux up the ureter into the lower part of the kidney, the reflux should be treated. It is unlikely to disappear with time. If this is the case, removal of the ureterocele and ureteral re-implantation (recreation of the flap valve) is recommended.

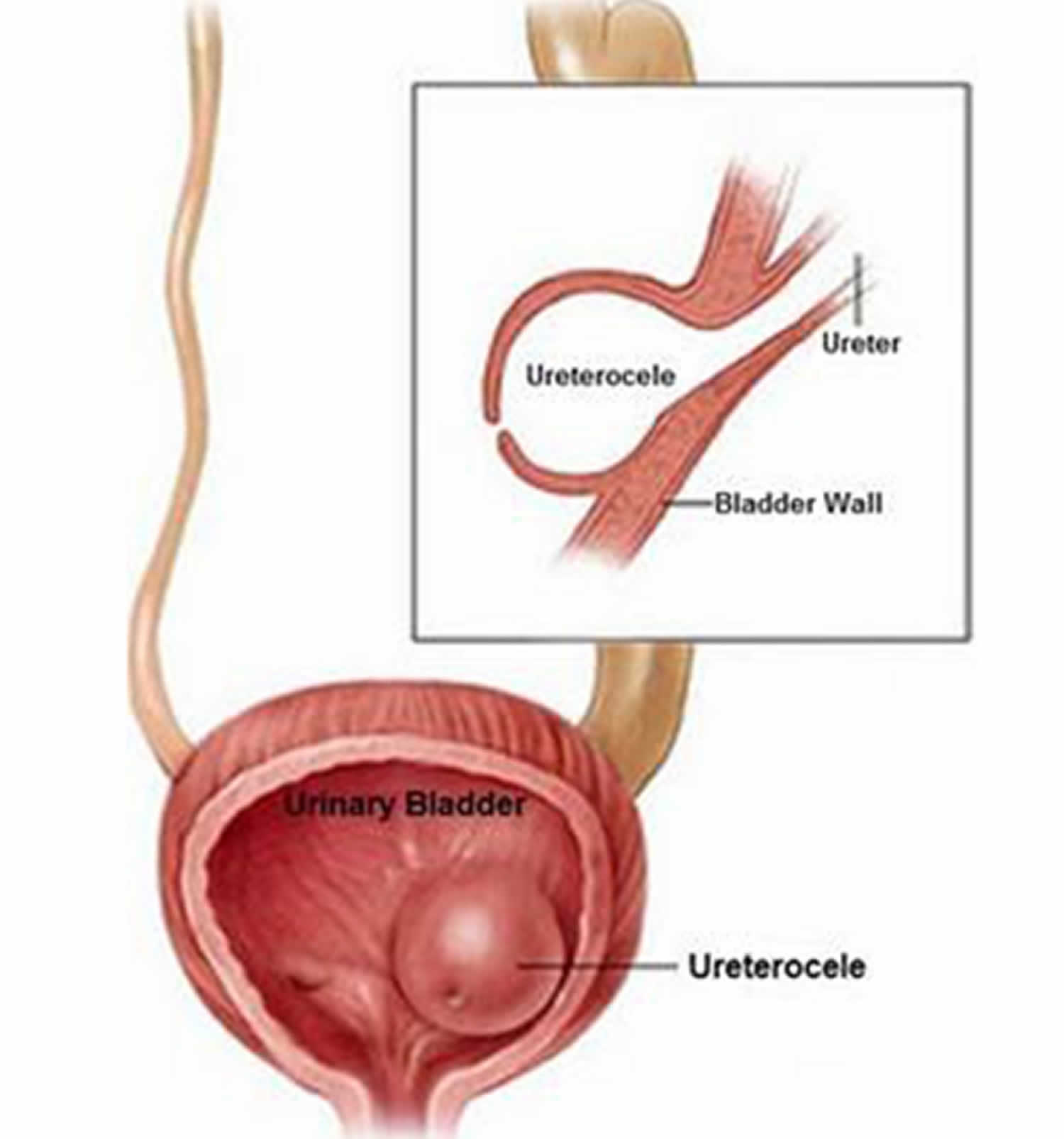

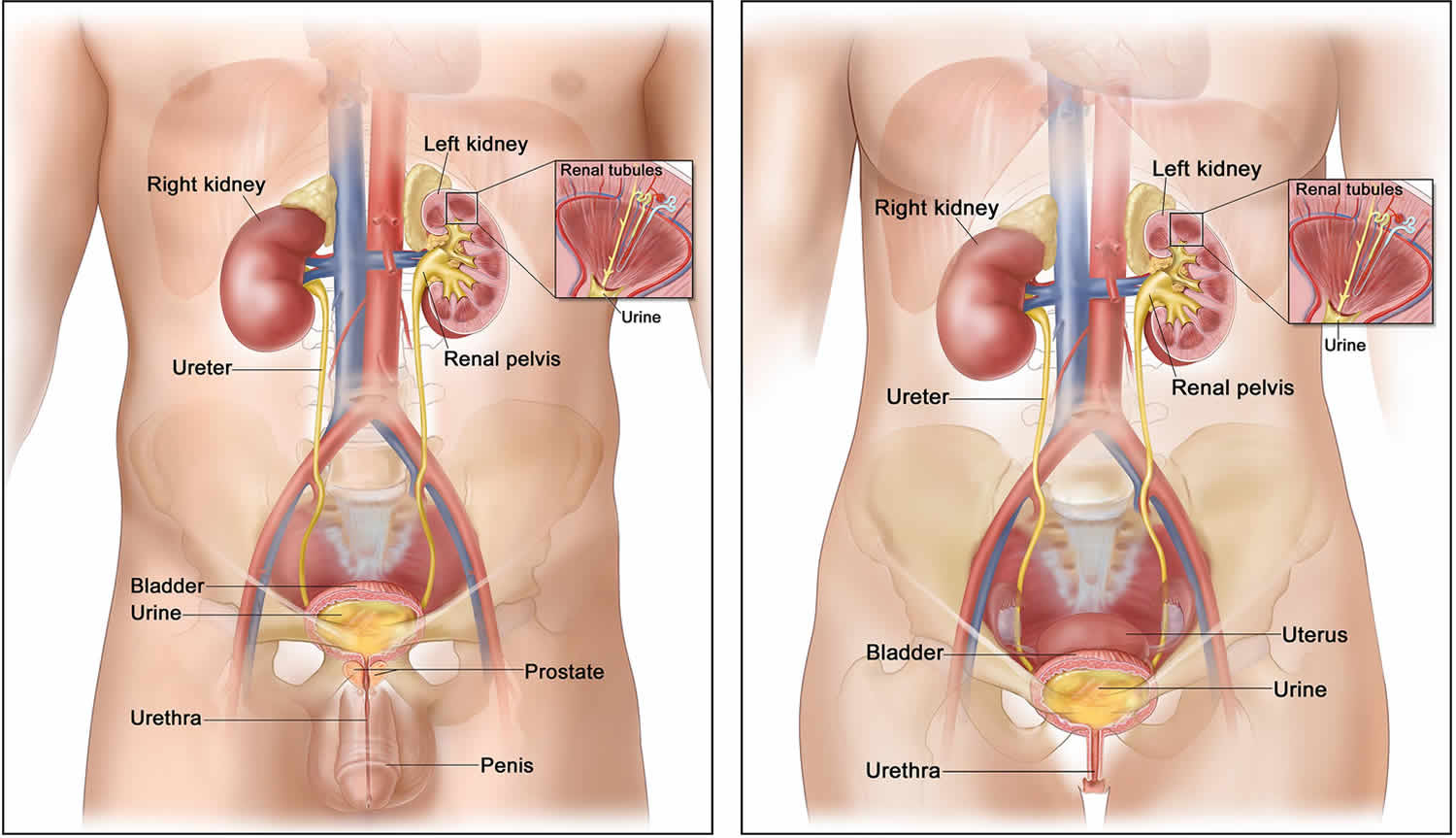

Ureter anatomy

Normally, your kidneys filter and remove waste and excess water from your blood to produce urine. Urine travels from your kidneys down narrow tubes called ureters. The ureters bring urine to the bladder, where it is then stored. There is a flap valve between the ureters and the bladder to keep urine flowing in only one direction. If urine wrongly flows back to the kidneys, this is a problem called vesicoureteral reflux (VUR).

When the bladder empties, urine flows out of the body through the urethra. This is the tube that starts at the bottom of the bladder. The urethra travels to the end of the penis in boys, or out the front of the vagina in girls.

Figure 2. Ureter anatomy

Ureterocele location and classification

Ureteroceles are classified by location. The most common system of classification is that of the urologic division of the American Academy of Pediatrics 7. Both types are the result of cystic ectasia of the subepithelial portion of the ureter as it enters the bladder:

- Intravesical ureterocele: occur at the normal vesicoureteric junction position

- Extravesical ureterocele: occur ectopically low and medial, near bladder neck/urethra

They pose a challenge for diagnosis and treatment because of the wide variety of anatomical abnormalities that may exist and the non-specific symptoms that patients present with.

Figure 3. Ureterocele types

Intravesical ureterocele (~25%)

Also known as “simple” or “orthotopic” ureterocele 8. Considerably less common than the ectopic variety and is almost always confined to the adult population. There is a congenital prolapse of a dilated distal ureter into the bladder lumen. Where they do occur in children, they usually cause symptoms. Bilateral in about 30% of cases 9.

Extravesical ureterocele (~75%)

Also known as “ectopic” ureterocele 7. Almost always associated with a duplicated collecting system and the result of abnormal embryogenesis. There is an abnormality in the early development of the intravesicular ureter, the ipsilateral kidney and its collecting system 10. It is significantly more common than the simple type.

Approximately 80% of cases are unilateral and may cause obstruction to the entire renal tract because of prolapse into the bladder neck causing bladder outlet obstruction. Additionally, ureteroceles may contain calculi.

A cecoureterocele is a subtype of extravesical ureterocele which extends inferiorly to involve the urethra. Rarely, it may herniate into the urethra and present as a perineal mass 11.

Ureterocele causes

The precise embryologic cause of the ureterocele remains unknown. Theorized causes include the following:

- Obstruction of the ureteral orifice

- Incomplete muscular development of the intramural ureter

- Excessive dilatation of the intramural ureter during the development of the bladder and trigone

The most commonly accepted theory behind ureterocele formation is obstruction of the ureteral orifice during embryogenesis, with incomplete dissolution of the Chwalla membrane. This is a primitive, thin membrane that separates the ureteral bud from the developing urogenital sinus. Failure of this membrane to completely perforate during development of the ureteral orifice is thought to explain the occurrence of a ureterocele.

Ureterocele symptoms

Usually there are no symptoms associated with ureterocele. Currently, most pediatric ureteroceles are found during routine prenatal screening. Adult ureteroceles may also be found incidentally during imaging studies, often obtained for complaints of unrelated symptomatology. Ureteroceles frequently do not have clinical sequelae in the adult population. However, when problems arise, presenting clinical features of ureteroceles may include the following:

- Side, back or cyclic abdominal pain

- Urinary tract infections (UTIs)

- Urosepsis

- Fever

- Painful urination

- Foul-smelling urine

- Blood in the urine (hematuria)

- Excessive urination

- Obstructive voiding symptoms

- Urinary retention

- Failure to thrive

- Ureteral calculus

Pathologic ureteroceles most often affect the pediatric population. In young infants, failure to thrive or urinary tract infection may be the first sign of a symptomatic ureterocele.

Complications of ureteroceles in both pediatric and adult populations occur because of the obstructive nature of the ureterocele and its anatomic location. Because of the distal ureteral obstruction, the ipsilateral renal moiety is often hydronephrotic or dysplastic. The degree of hydronephrosis may wax and wane depending on the amount of urine produced by the renal moiety. Cyclical expansion and decompression of the renal pelvis manifests as intermittent abdominal pain in older children and adults.

In the setting of untreated UTIs and hydronephrosis, affected older children and adults may reveal signs and symptoms of pyonephrosis or frank urosepsis. The dilated ureterocele may cause urinary stasis and is a risk factor for ureteral stone formation within the saccular cavity. When distal ureteral stones develop, they cannot pass spontaneously because of the obstructing ureterocele orifice. Presence of stones within a ureterocele is exclusive to the adult population. A prolapsing ureterocele in a female patient may cause physical obstruction of the bladder neck. Anatomic obstruction of the bladder neck by the cystic ureterocele may incite obstructive voiding symptoms or may precipitate acute urinary retention in both pediatric and adult populations. Intravesical ureterocele has also been reported to cause bladder outlet obstruction in an adult male 12.

Ureterocele complications

The main problem from ureterocele is kidney damage, and kidney infection. Urine blockage may damage the developing kidneys and reduce their ability to filter.

Reflux of urine backward to the kidney is also common, especially when there are two ureters in one kidney. This is because the ureterocele distorts the normal one-way valve between the ureter and bladder. Reflux into the opposite kidney may happen. There is also a small risk for kidney stones. In rare cases, ureterocele in girls can protrude outside the urethra and be visible as a balloon.

Ureterocele diagnosis

Often, ureteroceles can be seen during maternal ultrasounds before the birth of a child. Still, they may not be diagnosed until a child is seen for another problem, like a urinary tract infection.

Ultrasound is the first imaging test used to find ureterocele. Other imaging studies may be done to help understand what’s happening, and for treatment. For an infant or small child, the following tests may be done:

- A voiding cystourethrogram (VCUG) may be done to see the bladder in action. This is a series of X-rays of the bladder and lower urinary tract taken with a special dye. First a catheter is inserted in the urethra to fill the bladder with a water-based dye. It is removed. Then several X-rays are taken as the patient empties the bladder. These images allow radiologists to find problems in the flow of urine through the body.

- When a ureterocele has been found, it is also important to evaluate the kidneys for damage and evidence for blockage to urine flow across the ureterocele. A nuclear renal scan will provide ample information in this regard.

- In cases were the relevant anatomy is not clear, an MRI test may also be done. This will allow the surgeon to better prepare for surgery (if necessary).

Ureterocele treatment

The timing and type of treatment used for fetal ureterocele are based on a few things:

- The age and health of the patient

- Whether or not the kidney is affected

- Type of ureterocele

- Whether or not vesicoureteral reflux (VUR) is present

- Kidney function

- Surgeon preference

Sometimes, more than one procedure is needed. Sometimes, observation (no treatment) may be recommended.

The following are treatment options:

Observation alone is rarely a good option in symptomatic ureteroceles. Antibiotic prophylaxis is started in newborns with prenatal diagnosis of ureterocele, which decreases the overall incidence of urinary tract infection (UTI). In the setting of urosepsis with ureterocele, the physician must rapidly initiate aggressive antibiotic therapy. Antibiotics should be instituted during the initial diagnostic evaluation and during surgical intervention for both pediatric and adult ureteroceles.

Indications for surgical treatment for both pediatric and adult ureteroceles depend on the site of the ureterocele, the clinical situation, associated renal anomalies, and the size of the ureterocele. Treatment of the ureterocele is indicated to relieve obstruction and to preserve renal function. Indications for surgical intervention include the following:

- Recurrent UTI

- Urosepsis

- Ureteral calculi

- Intractable pain

- Renal compromise

Urgent decompression with endoscopic incision, followed by a definitive bladder reconstruction, is often required in cases of urosepsis or severe azotemia. Indications for intervention in the pediatric and adult population are identical. Contraindication for correction of a ureterocele is a small, asymptomatic ureterocele not causing any dilatation of the collecting system.

Goals of treatment include the following:

- Control of infection

- Preservation of renal function

- Protection of ipsilateral and contralateral renal units

- Maintenance of urinary continence

- Elimination of obstruction and reflux

The surgical approach is selected based on the following:

- Age of the patient

- Size and location of ureterocele

- Degree of renal function

- Presence and degree of vesicoureteral reflux

- Comorbid conditions (risk of anesthesia)

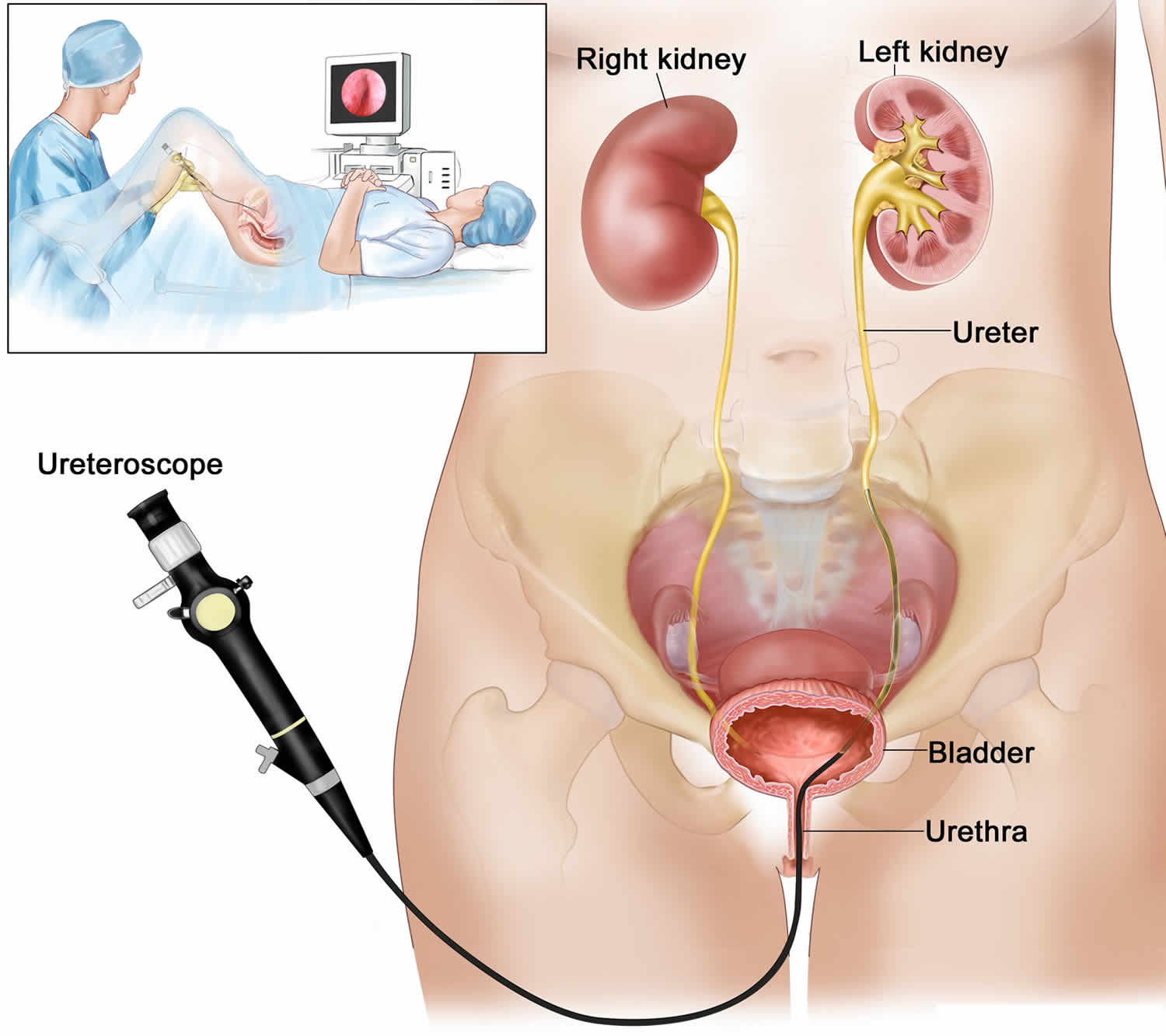

Ureterocele surgery

In the neonate or infant, transurethral puncture of the ureterocele or an upper tract approach (eg, heminephrectomy) are often the most feasible options, while excision of the ureterocele with bladder reconstruction or total reconstruction, including heminephrectomy, may be added to the therapeutic armamentarium in the older child (> 2 years). In the adult, transurethral unroofing of the ureterocele is a reasonable first-line approach, because the development of postoperative vesicoureteral reflux is less problematic than in the child.

For infants and children with an intravesical nonrefluxing ureterocele, endoscopic puncture is usually the first-line therapy because it is minimally invasive and has a high chance of providing definitive treatment 13. For those with a nonrefluxing, poorly functioning upper pole associated with an ectopic ureterocele, an upper pole heminephrectomy is a reasonable first-line therapy. Opinions and approaches vary the most in those children with ectopic ureteroceles associated with vesicoureteral reflux.

In the adult, transurethral unroofing of the ureterocele is a reasonable first-line approach, because the development of postoperative vesicoureteral reflux is less problematic than in the pediatric population.

Surgical therapy for both pediatric and adult ureteroceles may include any of the following:

- Endoscopic puncture

- Incision or transurethral unroofing of the ureterocele

- Upper pole heminephrectomy

- Excision of ureterocele and ureteral reimplantation

- Nephroureterectomy

Transurethral puncture

With this treatment, the ureterocele is punctured and decompressed. To do this a cystoscope (a thin tube with camaera and light on the end) is used. It usually takes 15 to 30 minutes and can be done without an overnight stay in the hospital. This treatment doesn’t use a large incision. But, if the ureterocele wall is thick, it may not work. If it doesn’t work, an open operation may be needed. Also, there is a slight risk of causing an obstructive flap valve. This would make it difficult to urinate. This treatment works best when the ureterocele is within the bladder (orthotopic).

With a thick-walled ureterocele, either a larger puncture or incision, or multiple punctures may be required to establish drainage. Multiple endoscopic procedures may be required to successfully decompress an ectopic ureterocele 14.

Endoscopic puncture also allows palliative decompression in children at high risk (secondary to concurrent medical illness), so that definitive reconstruction can be delayed until an adequate healing period has occurred. Antibiotic prophylaxis should be administered postoperatively in pediatric patients until voiding cystourethrography (VCUG) can be performed to assess for vesicoureteral reflux. Ectopic ureterocele and duplicated system are associated with a significantly higher rate of secondary procedures, which is most often related to the presence of reflux. Endoscopic treatment provides definitive therapy in only 10-40% of patients with ectopic ureteroceles, compared with 80-90% of patients with a single-system intravesical ureterocele.

Transurethral unroofing

Transurethral unroofing of a ureterocele in adults reliably achieves decompression and allows effective treatment of infection and calculi in symptomatic ureteroceles. Low transverse incision of the ureterocele, as described by Monfort and colleagues 14 creates a “flap-valve” effect and minimizes the chance of subsequent vesicoureteral reflux compared with transurethral resection of the ureterocele roof. The actual incidence of reflux after endoscopic unroofing in ureteroceles in adults is unknown because a large prospective adult series is lacking. However, several case reports have alluded to the fact that the incidence of reflux appears to be proportional to the type of incision made.

Vesicoureteral reflux in adults is not routinely treated with ureteral reimplantation. Rather, these patients are monitored expectantly, and the need for reimplantation is tailored to the individual. Data on the use of bulking agents for treatment of adult vesicoureteral reflux in these situations are lacking. The potential for vesicoureteral reflux limits the use of endoscopic unroofing in children.

Upper pole nephrectomy

In some cases, the upper half of the kidney does not function from a ureterocele. If there is no urine reflux in the second ureter, the damaged part of the kidney may be removed. Often, this operation is done either through a small cut under the ribs, or laparoscopically.

Upper pole heminephrectomy and partial ureterectomy

Upper pole heminephrectomy and partial ureterectomy with ureterocele decompression involves removal of the upper pole of the kidney, as well as the affected proximal ureter to the level of iliac vessels. The remaining distal ureterocele is not excised but rather is decompressed. This is the definitive treatment in patients with an obstructed ectopic ureterocele and a dysplastic upper pole, but without associated vesicoureteral reflux. If reflux is present preoperatively, the distal ureter should be ligated. Upper pole heminephrectomy and partial ureterectomy with ureterocele decompression is a reasonable alternative for adults in whom transurethral ureterocele unroofing has failed due to technical or anatomical difficulties.

Upper pole heminephrectomy and partial ureterectomy with ureterocele decompression has been reported to cause spontaneous resolution of grade I and II vesicoureteral reflux in 60% of cases, while higher grades of reflux necessitated bladder reconstruction in 96% of cases. While upper pole heminephrectomy provides effective decompression, the risk for subsequent bladder surgery may be significant, especially if reflux is present.

Factors that may predict the likelihood of future surgical intervention include the following:

- High-grade reflux (grades III, IV, V)

- Complications resulting from remaining stump of upper ureter (ie, UTI, calculus)

- Poor detrusor backing behind the remaining ureterocele

Upper pole heminephrectomy is an excellent first-line procedure for the relatively rare child with minimally functioning upper pole and no reflux. However, the patient and family should be counseled regarding the potential need for further surgical procedures.

Nephrectomy

If the entire kidney does not work because of the ureterocele, it must be removed. Nephroureterectomy is performed in patients with single-system ureterocele and a poorly functioning kidney. Usually this can be done laparoscopically. Sometimes a small incision is needed.

A retrospective review reported a 4% incidence of nephroureterectomy in children with single-system ureterocele and nonfunctioning renal unit 15. The traditional method of correcting an ectopic ureterocele in a duplex system has been to perform a total reconstruction. This involved a bladder-level operation with ureterocele excision and reimplantation of the lower pole ureter, followed by a flank incision and upper pole heminephrectomy. Since most ureteroceles typically present in young children, total reconstruction was technically challenging, and complications were common.

Removal of the ureterocele and ureteral reimplantation

If the ureterocele must be removed, then an operation is done. Ureterocele excision with ureteroneocystostomy is indicated as a primary procedure if the patient has significant vesicoureteral reflux in the lower pole moiety and/or significant contralateral vesicoureteral reflux. For this surgery, the bladder is opened, the ureterocele is removed, the floor of the bladder and bladder neck are rebuilt, and the ureteral flap valve recreated to prevent urine from flowing backward to the kidney. The operation is done with a small incision in the lower abdomen. It is a complex surgery, but it is successful 90-95% of the time.

Both ipsilateral ureters may be reimplanted within a common sheath or via ureteroureterostomy. Note that common sheath reimplantation has the distinct disadvantage of reimplanting a very dilated distal ureter into the small bladder of an infant. The decision whether to taper the ureters must be made on an individual basis. This operation is commonly delayed until the child is older (aged approximately 2 years) following endoscopic puncture as an infant. Ureteral reimplantation is not commonly performed in adults as most patients respond favorably to endoscopic unroofing of the ureterocele.

In the pediatric population, ureterocele excision and ureteral reimplantation is commonly a secondary procedure (after previous heminephrectomy or endoscopic incision of a ureterocele) because of recurrent urinary tract infections, voiding disturbance, persistent vesicoureteral reflux, or obstruction. Significant vesicoureteral reflux on initial VCUG usually indicates that lower-tract reconstruction will be necessary. Of note, if ureteral reimplant is performed as first-line treatment in the appropriately selected patient, the rate of secondary surgery is low.

Ureteropyelostomy or upper-to-lower ureteroureterostomy

Ureteropyelostomy is an operation that joins the upper pole ureter to the lower pole renal pelvis. If the upper part of the ureter works well, and there is no reflux in the lower part ureter, one option is to connect the obstructed part to the non-obstructed part of the ureter or kidney. The operation is done with a small incision in the lower abdomen. The success rate is 95%.

Ureteropyelostomy is preferred in both children and adults if the affected renal unit demonstrates significant function on nuclear renography and there is no associated vesicoureteral reflux. Alternatively, a high ureteroureterostomy may also be performed.

Antibiotics

Antibiotics are used to fight bacteria and prevent kidney infection. A child with a possible urine block or urine reflux may be given antibiotics to prevent infections until the defect is corrected.

Follow-up

Follow-up care consists of serial monitoring of renal function, periodic evaluation of voiding symptoms and bladder function, and interval radiologic studies to assess renal growth, hydroureteronephrosis, and vesicoureteral reflux.

Ureterocele prognosis

No single approach is appropriate for all patients with ureteroceles; therefore, each case must be tailored to the individual. An experienced surgeon must be armed with various surgical techniques that can be tailored to effectively treat different types of ureterocele malformations. When an appropriate operation is used to correct a specific abnormality, the outcomes remain excellent in both pediatric and adult patients.

A retrospective analysis 16 comparing the results of 12 neonates with ureterocele treated by laser-puncture to 20 neonates with ureterocele treated by electrosurgery-incision found both techniques were highly effective in relieving the obstruction. There were no significant differences regarding hospitalization, need for retreatment, and the occurrence of complications.

References- Schultza K, Todab LY. Genetic Basis of Ureterocele. Curr Genomics. 2016;17(1):62‐69. doi:10.2174/1389202916666151014222815 https://www.ncbi.nlm.nih.gov/pmc/articles/PMC4780476

- Ureterocele. https://www.urologyhealth.org/urologic-conditions/ureterocele

- Löcherbach F, Wolfsgruber P, Wyler S, Kwiatkowski M. Single-system orthotopic ureterocele with calculus masquerading as a bladder tumour – A case report and review of literature. Urol Case Rep. 2018 Nov. 21:64-66.

- Shamsa A, Asadpour AA, Abolbashari M, Hariri MK. Bilateral simple orthotopic ureteroceles with bilateral stones in an adult: a case report and review of literature. Urol J. 2010;7(3):209‐211. http://journals.sbmu.ac.ir/urolj/index.php/uj/article/view/757/496

- Ureterocele. https://emedicine.medscape.com/article/451105-overview

- Villanueva CA. Open vs robotic infant ureteroureterostomy. J Pediatr Urol. 2019 Aug. 15 (4):390.e1-390.e4.

- Tekgül et al. EAU Guidelines on European Society for Paediatric Urology. European Association of Urology. 2016. https://uroweb.org/wp-content/uploads/EAU-Guidelines-Paediatric-Urology-2016-1.pdf

- Berrocal T, López-Pereira P, Arjonilla A, Gutiérrez J. Anomalies of the distal ureter, bladder, and urethra in children: embryologic, radiologic, and pathologic features. Radiographics. 2002;22(5):1139‐1164. doi:10.1148/radiographics.22.5.g02se101139

- Dähnert W. Radiology review manual 7th Edition. Lippincott Williams & Wilkins. ISBN:1609139437

- Ayers, Elizabeth. Incidental Sonographic Finding of Bilateral Ureteroceles Journal of Diagnostic Medical Sonography. 22 (2): 123. doi:10.1177/8756479306286596

- Florian L, Stefan P, Mark M. A Prolapsed Cecoureterocele in an Adult Treated Conservatively: Highly Rare, but Existent. Case Rep Urol. 2016;2016:5049072. doi:10.1155/2016/5049072 https://www.ncbi.nlm.nih.gov/pmc/articles/PMC5039285

- Sekine H, Kojima S, Mine M, Yokokawa M. Intravesical ureterocele presenting bladder outlet obstruction in an adult male. Int J Urol. 1996 Jan. 3(1):74-6.

- Timberlake MD, Corbett ST. Minimally invasive techniques for management of the ureterocele and ectopic ureter: upper tract versus lower tract approach. Urol Clin North Am. 2015 Feb. 42 (1):61-76.

- Monfort G, Morisson-Lacombe G, Coquet M. Endoscopic treatment of ureteroceles revisited. J Urol. 1985 Jun. 133(6):1031-3.

- Shimada K, Matsumoto F, Matsui F. Surgical treatment for ureterocele with special reference to lower urinary tract reconstruction. Int J Urol. 2007 Dec. 14(12):1063-7.

- Ilic P, Jankovic M, Milickovic M, Dzambasanovic S, Kojovic V. Laser-puncture Versus Electrosurgery-incision of the Ureterocele in Neonatal Patients. Urol J. 2018 Mar 18. 15 (2):27-32.