What is a ventriculoperitoneal shunt

Ventriculoperitoneal shunt also known as cerebral shunt, is surgery to treat excess cerebrospinal fluid (CSF) in the cavities (ventricles) of the brain called hydrocephalus 1. If left unchecked, excess cerebrospinal fluid (CSF) can increase intracranial pressure (ICP) resulting in herniation, intracranial hematoma, cerebral edema, or crushed brain tissue. In children, untreated hydrocephalus can lead to many adverse effects including increase irritabilities, chronic headaches, learning difficulties, visual disturbances, and in more advanced cases severe mental retardation 2.

The ventricles of the brain are a communicating network of cavities located within the brain parenchyma. The ventricular system is composed of two lateral ventricles, the cerebral aqueduct, and the third and fourth ventricle. The choroid plexuses in the ventricles produce CSF, which fills the subarachnoid space and ventricles in a constant cycle of production and reabsorption 3.

Children may be born with hydrocephalus. Hydrocephalus can occur with other birth defects of the spinal column or brain. Hydrocephalus can also occur in older adults. Ventriculoperitoneal shunt surgery should be done as soon as hydrocephalus is diagnosed. Ventriculoperitoneal shunts are used to treat hydrocephalus and shunt cerebrospinal fluid from the lateral ventricles into the peritoneum. Tapping a shunt is performed for both diagnostic and therapeutic reasons (e.g., evaluate for infection and relieve blockage). Alternative surgeries may be proposed. Your doctor can tell you more about these options.

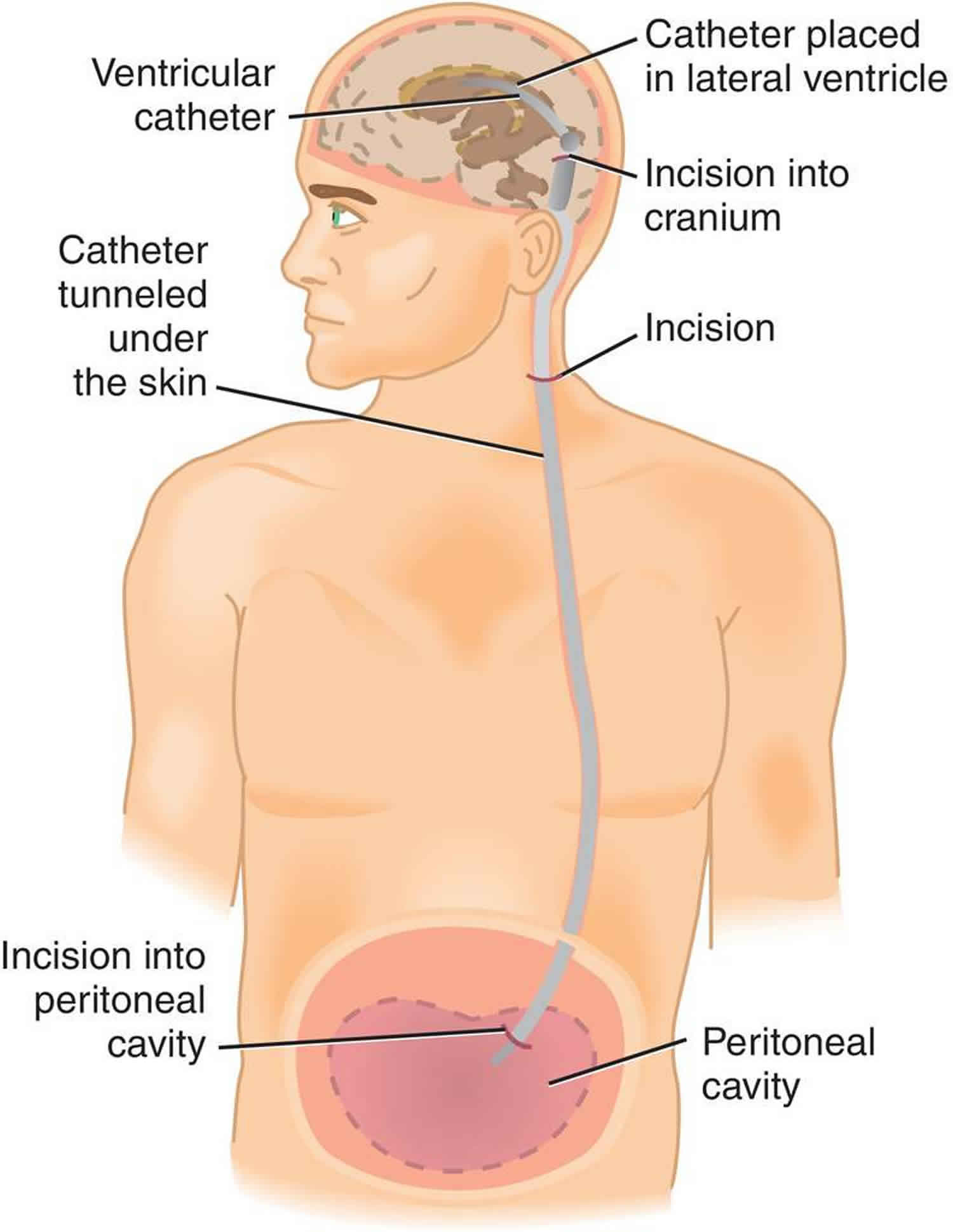

Ventriculoperitoneal shunt surgery (VP shunt surgery) helps control pressure in your brain by draining extra fluid out of your brain and into your belly. During ventriculoperitoneal shunt surgery, the doctor placed two small tubes (catheters) and a valve under your skin.

A ventriculoperitoneal shunt consists of a valve housing connected to a catheter, the distal end of which is placed in the peritoneal cavity. The main differences between shunts are the materials used to construct them, the types of valve, and whether the valve is programmable or not. Advances in the biotechnologies are leading to progressive changes in shunt components. These advanced components are expected to reduce shunt malfunctions and optimize neurosurgical patient care.

Ventriculoperitoneal shunt can be lifesaving, but the eventual outcome depends on the reason why the ventriculoperitoneal shunt was inserted. For benign disorders, most patients have a good outcome. However, for malignant tumors, the outcomes are usually poor; often these patients die from other causes unrelated to the ventriculoperitoneal shunt. The complication rates of ventriculoperitoneal shunt shunts range from 2-20%. In addition, ventriculoperitoneal shunt revision is required in about 5-10% of neonates and young children 4.

Ventriculoperitoneal shunt indications

Conditions that typically requiring ventriculoperitoneal shunting include the following 1:

- Congenital hydrocephalus

- Tumors leading to CSF blockage of the lateral or third ventricles, the posterior fossa, and intraspinal tumors.

- Post-hemorrhagic hydrocephalus

- Spina bifida causes the development of hydrocephalus because the cerebellum blocks the flow of CSF in a development of Chiari Malformation II

- Congenital aqueductal stenosis is a genetic disorder which can cause deformations of the nervous system and is associated with mental retardation, abducted thumbs, and spastic paraplegia

- Craniosynostosis occurs when the sutures of the skull close too early with sutures fusing before the brain stops growing causing an increase in ICP leading to hydrocephalus

- Post-meningitic hydrocephalus caused by meningitis can inhibit CSF absorption

- Dandy-Walker syndrome presents with a cystic deformity of the fourth ventricle, hypoplasia of the cerebellar vermis, and an enlarged posterior fossa

- Arachnoid cysts are a defect caused when CSF forms a collection that is trapped in the arachnoid membranes resulting in a block of the normal flow of CSF from the brain resulting in hydrocephalus. Common locations of arachnoid cysts are the middle fossa and the posterior fossa. The most common symptoms are nausea and vertigo

- Idiopathic intracranial hypertension is a rare neurological disorder affecting approximately 1 in 100,000 people, usually women of childbearing age. It can raise intracranial pressure and result in permanent loss of vision.

Ventriculoperitoneal shunt contraindications

Absolute contraindications include infection over the entry site 1. Relative contraindications include coagulopathy and lack of shunt imaging.

Ventriculoperitoneal shunt placement

Placement of cerebral shunt and its location is determined based on the type and location of the blockage causing hydrocephalus. All brain ventricles are candidates for shunting. These include the lateral ventricles, the third ventricle, and the fourth ventricle. The catheter placed in the cerebral ventricle is called the proximal portion of the shunt implying proximity to the brain. The most common proximal shunt location is the right lateral ventricle. The distal (post valve) catheter can be placed in the cardiac atrium via venous, to the chest cavity, bladder, and most commonly placed in the abdomen in peritoneal space. Overall, other locations include the heart and lungs found to be more morbid compared to the abdomen. In all cases, however, the distal end of the catheter can be located in any tissue with epithelial cells capable of absorbing the incoming cerebrospinal fluid (CSF).

A subgaleal shunt is a temporary measure used in infants who are too small or premature to tolerate other shunts. The surgeon forms a pocket beneath the subgaleal space and allows the CSF to drain from the ventricles, creating a fluid-filled swelling on the infant’s scalp. As the child grows, these shunts are later converted to a ventriculoperitoneal (VP) or another shunt types 5.

Ventriculoperitoneal shunt procedure

Ventriculoperitoneal shunt procedure is done in the operating room under general anesthesia by practicing neurological surgeons. Ventriculoperitoneal shunt procedure takes about 1 1/2 hours. A tube (catheter) is passed from the cavities of the head to the abdomen to get rid of the excess cerebrospinal fluid (CSF). A pressure valve and an anti-syphon device ensure that just the right amount of fluid is drained.

Before the ventriculoperitoneal shunt procedure

All patients need appropriate preoperative workup and informed consent for surgery and general anesthesia.

If the procedure is not an emergency (it is planned surgery):

- Tell the health care provider what medicines, supplements, vitamins, or herbs the person takes.

- Take any medicine the provider said to take with a small sip of water.

Ask the provider about limiting eating and drinking before the surgery.

Follow any other instructions about preparing at home. This may include bathing with a special soap.

Ventriculoperitoneal shunt procedure

Equipment needed to perform the procedure includes:

- Sterile gloves

- Povidone-iodine or chlorhexidine solution

- Sterile fenestrated drape

- Butterfly needles, 23 or 25 gauge

- Syringe, 3 mL to 5 mL

- Three-way stopcock

- Gauze swabs

- Wound dressing

- Numbered specimen tubes for CSF

- Cerebrospinal fluid manometer

The ventriculoperitoneal shunt procedure is done as follows:

- The patient should be placed supine with the head oriented so that the shunt reservoir lies uppermost. The reservoir is normally located on the right side of the head and feels like a smooth dome under the skin.

- An area of hair on the head is shaved. This may be behind the ear or on the top or back of the head.

- The surgeon makes a skin incision behind the ear. Another small surgical cut is made in the belly.

- A small hole is drilled in the skull. One end of the catheter is passed into a ventricle of the brain. This can be done with or without a computer as a guide. It can also be done with an endoscope that allows the surgeon to see inside the ventricle.

- A second catheter is placed under the skin behind the ear. It is sent down the neck and chest, and usually into the belly area. Sometimes, it stops at the chest area. In the belly, the catheter is often placed using an endoscope. The doctor may also make a few more small cuts, for instance in the neck or near the collarbone, to help pass the catheter under the skin.

- A valve is placed underneath the skin, usually behind the ear. The valve is connected to both catheters. When extra pressure builds up around the brain, the valve opens, and excess fluid drains through the catheter into the belly or chest area. This helps lower intracranial pressure. A reservoir on the valve allows for priming (pumping) of the valve and for collecting the CSF if needed.

- The person is taken to a recovery area and then moved to a hospital room.

Ventriculoperitoneal shunt recovery

The person may need to lie flat for 24 hours the first time a shunt is placed. After surgery, your neck or belly may feel tender. You will probably feel tired, but you should not have much pain. For a few weeks after surgery, you may have headaches.

How long the hospital stay is depends on the reason the shunt is needed. The health care team will closely monitor the person. IV fluids, antibiotics, and pain medicines will be given if needed.

It is common to feel some fluid moving around in your scalp. This will go away as your scalp heals. The area around the stitches or staples may feel tender for a week or more. If needed, the doctor will remove your stitches or staples 5 to 10 days after surgery.

The shunt will not limit your activities. There will be a lump on your head where the valve is. This lump may not show when your hair grows back. You may or may not feel the shunt underneath your skin.

In some cases, your doctor may need to adjust your shunt valve so the right amount of fluid is draining. Watch for signs of infection or signs that the shunt is not working right. If the shunt gets infected or stops working well, it may need to be removed or replaced. Without problems, your shunt may be left in place for years.

Follow the provider’s instructions about how to take care of the shunt at home. This may include taking medicine to prevent infection of the shunt.

How can you care for yourself at home?

Any stitches or staples that you can see will be taken out in about 7 to 14 days.

- If you have strips of tape on the incisions the doctor made, leave the tape on for a week or until it falls off.

- Wash your incision areas daily with warm, soapy water, and gently pat them dry. Don’t use hydrogen peroxide or alcohol, which can slow healing. You may cover the areas with a gauze bandage if they weep or rub against clothing. Change the bandages every day.

- Keep the areas clean and dry.

All parts of the shunt are underneath the skin. At first, the area at the top of the shunt may be raised up underneath the skin. As the swelling goes away and your child’s hair grows back, there will be a small raised area about the size of a quarter that is usually not noticeable.

Self-care

DO NOT shower or shampoo your child’s head until the stitches and staples have been taken out. Give your child a sponge bath instead. The wound should not soak in water until the skin is completely healed.

DO NOT push on the part of the shunt that you can feel or see underneath your child’s skin behind the ear.

Your child should be able to eat normal foods after going home, unless the provider tells you otherwise.

Your child should be able to do most activities:

- If you have a baby, handle your baby the way you would normally. It is OK to bounce your baby.

- Older children can do most regular activities. Talk with your provider about contact sports.

- Most of the time, your child may sleep in any position. But, check this with your provider as each child is different.

Your child may have some pain. Children under 4 years old may take acetaminophen (Tylenol). Children age 4 and older may be prescribed stronger pain medicines, if needed. Follow your provider’s instructions or instructions on the medicine container, about how much medicine to give your child.

The major problems to watch for are an infected shunt and a blocked shunt.

Call your child’s doctor if your child has:

- Confusion or seems less aware

- Fever of 100.4 °F (38°C) or higher

- Pain in the belly that does not go away

- Stiff neck or headache

- No appetite or is not eating well

- Veins on the head or scalp that look larger than they used to

- Problems in school

- Poor development or has lost a developmental skill previously attained

- Become more cranky or irritable

- Redness, swelling, bleeding, or increased discharge from the incision

- Vomiting that does not go away

- Sleep problems or is more sleepy than usual

- High-pitched cry

- Been looking more pale

- A head that is growing larger

- Bulging or tenderness in the soft spot at the top of the head

- Swelling around the valve or around the tube going from the valve to their belly

- A seizure

Call your doctor now or seek immediate medical care if:

- You feel new bumps on your head 3 to 5 days after surgery or the bumps get bigger after 2 weeks.

- There is redness or swelling along the shunt.

- You have trouble thinking clearly.

- You have a fever with a stiff neck or a severe headache.

- Your incision comes open.

- You have signs of infection, such as:

- Increased pain, swelling, warmth, or redness.

- Red streaks leading from the incision.

- Pus draining from the incision.

- Swollen lymph nodes in your neck, armpits, or groin.

- A fever.

- You have any sudden vision changes.

- You have new or worse headaches.

- You are sleeping more than you are awake.

- You fall and hit your head.

- You have pain that does not get better after you take pain medicine.

- You have a fever over 100.4 °F (38°C).

- You throw up.

Watch closely for changes in your health, and be sure to contact your doctor or nurse call line if you have any problems.

Activity

- Rest when you feel tired. Getting enough sleep will help you recover.

- Do not touch the valve on your head.

- It is okay for you to lie on the side of your head with the shunt.

- For 6 weeks, do not do any activity that may cause you to hit your head.

- You will probably be able to return to work in less than 1 week.

- After your doctor says it is okay to remove the bandages, you can shower. Afterward, be sure to pat the incision areas dry.

- Do not swim or bathe until your stitches or staples are removed.

- Check with your doctor about when it is safe to travel by plane.

Diet

- The tube in your belly will not affect how you digest food. You can eat as usual. If your stomach is upset, try bland, low-fat foods like plain rice, broiled chicken, toast, and yogurt.

- You may notice that your bowel movements are not regular right after your surgery. This is common. Try to avoid constipation and straining with bowel movements. You may want to take a fiber supplement every day. If you have not had a bowel movement after a couple of days, ask your doctor about taking a mild laxative.

Medicines

- Your doctor will tell you if and when you can restart your medicines. He or she will also give you instructions about taking any new medicines.

- If you take blood thinners, such as warfarin (Coumadin), clopidogrel (Plavix), or aspirin, be sure to talk to your doctor. He or she will tell you if and when to start taking those medicines again. Make sure that you understand exactly what your doctor wants you to do.

- Take pain medicines exactly as directed.

- If the doctor gave you a prescription medicine for pain, take it as prescribed.

- If you are not taking a prescription pain medicine, ask your doctor if you can take an over-the-counter medicine.

- Do not take two or more pain medicines at the same time unless the doctor told you to. Many pain medicines have acetaminophen, which is Tylenol.

- Too much acetaminophen (Tylenol) can be harmful.

- If you think your pain medicine is making you sick to your stomach:

- Take your medicine after meals (unless your doctor has told you not to).

- Ask your doctor for a different pain medicine.

- If your doctor prescribed antibiotics, take them as directed. Do not stop taking them just because you feel better. You need to take the full course of antibiotics.

Ventriculoperitoneal shunt prognosis

Ventriculoperitoneal shunt placement is usually successful in reducing pressure in the brain. But if hydrocephalus is related to other conditions, such as spina bifida, brain tumor, meningitis, encephalitis, or hemorrhage, these conditions could affect the prognosis. How severe hydrocephalus is before surgery also affects the outcome.

Ventriculoperitoneal shunt malfunction

A problem can happen anywhere in the ventriculoperitoneal shunt. For example:

- A part of a ventriculoperitoneal shunt might be damaged, or a tube might have moved from its site.

- A ventriculoperitoneal shunt can become blocked by body tissue or other material.

- A ventriculoperitoneal shunt can become infected. The infection might be in the brain fluid and then spread into the shunt. This is most common soon after a child gets a shunt, but it can happen later. The infection makes the fluid get thicker. Thickened fluid might move out of the brain more slowly, or it might stop moving at all.

What are the signs of ventriculoperitoneal shunt malfunction?

If the ventriculoperitoneal shunt stops working as it should, your child may not feel well. He or she may not be as alert or active as usual. Your child may be cranky or have a headache. He or she may not want to eat very much or may vomit.

You might see swelling where the shunt enters your child’s head. If there is an infection, your child may have a fever.

How is ventriculoperitoneal shunt malfunction diagnosed?

Your doctor will ask what symptoms your child has and when they started. Your doctor likely will do an imaging test like an MRI to help find out what might be wrong with the shunt. He or she may take some fluid from the shunt to check for infection.

How is ventriculoperitoneal shunt malfunction treated?

If the ventriculoperitoneal shunt is damaged or blocked with tissue, that part of the shunt may be able to be replaced. That could be a valve, a tube, or another part of the shunt.

If there’s an infection, the ventriculoperitoneal shunt may need to be removed. Your child will get antibiotics to treat the infection. After the infection is gone, a new shunt will be put in if needed. While the ventriculoperitoneal shunt is gone, your child may have a temporary drain to remove the fluid. Sometimes a temporary sac is used to hold fluids in place.

Call your locale emergency services number anytime you think your child may need emergency care. For example, call if:

- Your child has a seizure.

- You passed out (lost consciousness).

- You have sudden chest pain and shortness of breath, or you cough up blood.

- You have severe trouble breathing.

- It is hard to think, move, speak, or see.

- Your body is jerking or shaking.

Call your doctor now or seek immediate medical care if:

- Your child has signs of infection, such as:

- Increased pain, swelling, warmth, or redness over the area.

- Red streaks leading from the area.

- Pus draining from the area.

- A fever.

- Your child is not acting normally or is more cranky.

- Your child has a headache that doesn’t get better.

- Your child is much less alert than usual.

- Your child is vomiting.

- Your child has a swollen and firm “soft spot” (if a baby).

- Your child has trouble with walking and balance.

Watch closely for changes in your child’s health, and be sure to contact your doctor if your child has any problems.

Ventriculoperitoneal shunt complications

Risks for anesthesia and surgery in general are:

- Reactions to medicines or breathing problems

- Bleeding, blood clots, or infection

Ventriculoperitoneal shunt complications include the following:

- Blood clot or bleeding in the brain

- Bleeding from subcutaneous vessels during the tap

- Brain swelling

- Hole in the intestines (bowel perforation), which can occur later after surgery

- Leakage of CSF fluid under the skin from puncture site

- Infection of the shunt, brain, or in the abdomen due to skin flora entering the shunt, usually Staphylococcus epidermidis

- Damage to brain tissue

- Seizures

- Ventricular collapse due to rapid aspiration of CSF from a shunt can result in collapse of the ventricles, especially in slit ventricles

- The misplaced tap can result in the wrong section of tubing is punctured or that components adjacent to the reservoir.

The ventriculoperitoneal shunt may stop working. If this happens, fluid will begin to build up in the brain again. As a child grows, the ventriculoperitoneal shunt may need to be repositioned.

References- Fowler JB, Mesfin FB. Ventriculoperitoneal Shunt. [Updated 2019 Jan 28]. In: StatPearls [Internet]. Treasure Island (FL): StatPearls Publishing; 2019 Jan-. Available from: https://www.ncbi.nlm.nih.gov/books/NBK459351

- Hanna RS, Essa AA, Makhlouf GA, Helmy AA. Comparative Study Between Laparoscopic and Open Techniques for Insertion of Ventriculperitoneal Shunt for Treatment of Congenital Hydrocephalus. J Laparoendosc Adv Surg Tech A. 2019 Jan;29(1):109-113.

- Erps A, Roth J, Constantini S, Lerner-Geva L, Grisaru-Soen G. Risk factors and epidemiology of pediatric ventriculoperitoneal shunt infection. Pediatr Int. 2018 Dec;60(12):1056-1061

- Junaid M, Ahmed M, Rashid MU. An experience with ventriculoperitoneal shunting at keen’s point for hydrocephalus. Pak J Med Sci. 2018 May-Jun;34(3):691-695.

- Rinaldo L, Lanzino G, Elder BD. Predictors of distal malfunction after ventriculoperitoneal shunting for idiopathic normal pressure hydrocephalus and effect of general surgery involvement. Clin Neurol Neurosurg. 2018 Nov;174:75-79.