Volkmann’s contracture

Volkmann’s contracture also called Volkmann ischemic contracture, is a deformity of the hand, fingers, and wrist caused by fibrosis and contracture of the forearm 1. Volkmann’s ischemic contracture is caused by ischemic injury to the deep tissues enclosed in the tight unyielding osteo-facial compartments secondary to neglected acute compartment syndrome. Volkmann’s ischemic contracture may be associated with malunion or non-union of forearm fractures.

It is now well recognized that Volkmann ischemic contracture can develop from many different injuries, as long as the injuries cause swelling of the soft tissues that are contained in relatively nondistensible osseofascial compartments 2. As a result of this swelling, intramuscular pressure is elevated to a magnitude sufficient to occlude capillary perfusion. The compartments with the least ability to expand are most severely affected by this ischemic insult. Because the deep flexor compartment of the forearm lies next to the bone, it is the first and most severely affected 3. Variable levels of necrosis and fibrosis, though to a lesser degree, may also be evident in the flexor digitorum superficialis and the superficially located muscles such as the wrist flexors. The muscle degeneration which follows is most marked in the middle, and its extent decreases peripherally, so that a so-called ellipsoid-shaped infarct 3 may be the end result. Nerve trunks running in the ischemic zone also suffer damage; this is initially caused by ischemia but is later aggravated by the subsequent muscle fibrosis.

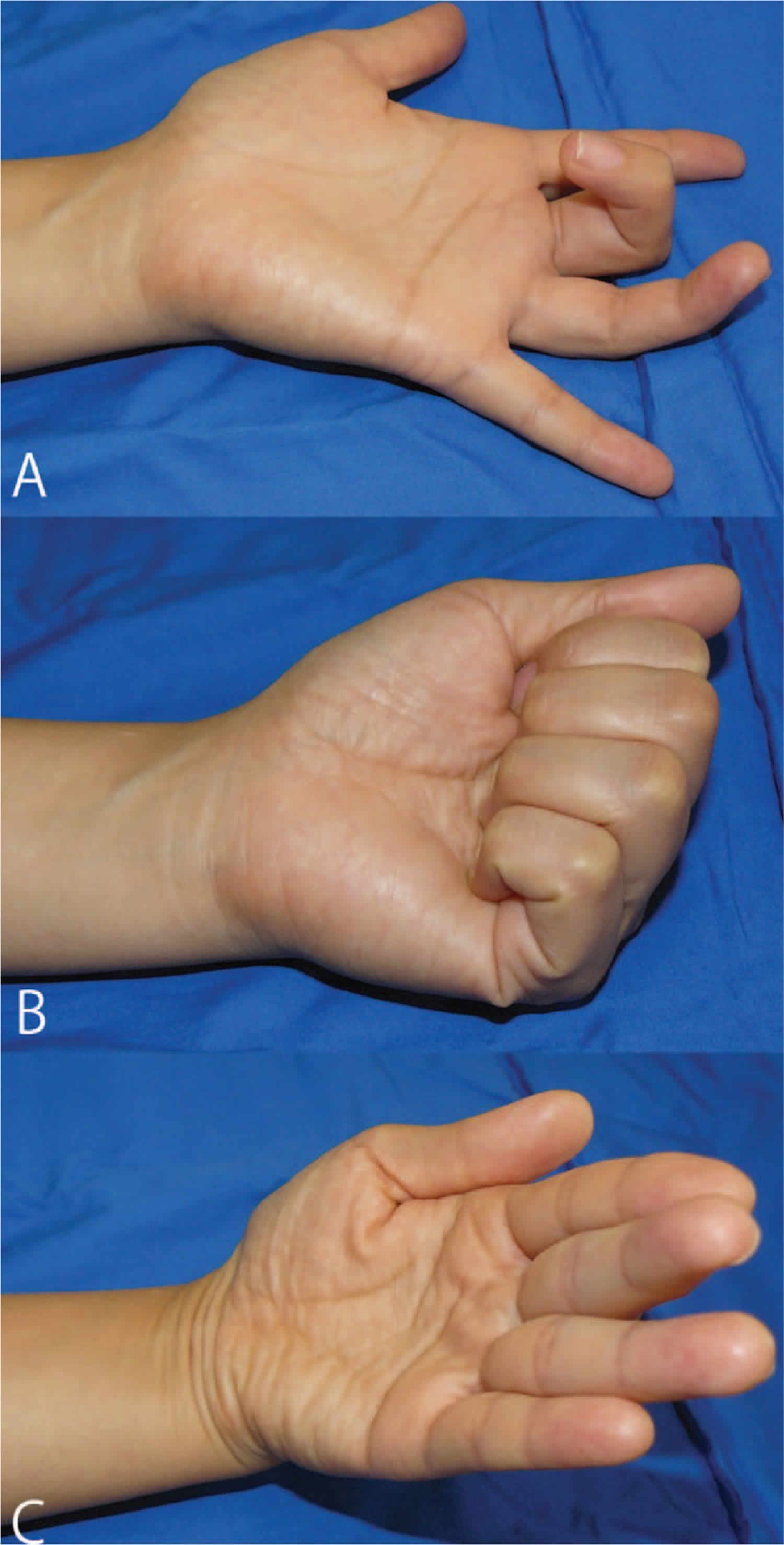

Figure 1. Volkmann ischemic contracture

Footnote: Preoperative findings of the left hand. (A, B) The long finger shows severe flexion contracture, and the ring finger shows a mild flexion contracture with the wrist in the neutral position. (C) The flexion contractures of these 2 fingers are reduced with the wrist in the palmar flexion position.

[Source 4 ]Volkmann’s ischemic contracture causes

Volkmann’s contracture occurs when there is a lack of blood flow (ischemia) to the forearm. This occurs when there is increased pressure due to swelling, a condition called compartment syndrome.

Injury to the arm, including a crush injury or fracture, can lead to swelling that presses on blood vessels and decreases blood flow to the arm. A prolonged decrease in blood flow injures the nerves and muscles, causing them to become stiff (scarred) and shortened.

When the muscle shortens, it pulls on the joint at the end of the muscle just as it would if it were normally contracted. But because it is stiff, the joint remains bent and stuck. This condition is called a contracture.

In Volkmann’s ischemic contracture, the muscles of the forearm are severely injured. This leads to contracture deformities of the fingers, hand, and wrist.

There are three levels of severity in Volkmann’s ischemic contracture:

- Mild – contracture of 2 or 3 fingers only, with no or limited loss of feeling

- Moderate – all fingers are bent (flexed) and the thumb is stuck in the palm; the wrist may be bent stuck, and there is usually loss of some feeling in the hand

- Severe – all muscles in the forearm that both flex and extend the wrist and fingers are involved; this is a severely disabling condition

Conditions that can cause increased pressure in the forearm include:

- Animal bites

- A forearm fracture

- Bleeding disorders

- Burns

- Excessive exercise

- Injection of certain medicines into the forearm

- Injury of the blood vessels in the forearm

- Surgery on the forearm

Sundararaj et al. 5, in his study of 196 cases of Volkmann’s ischemic contracture, reported that tight external splintage for supracondylar fractures of the humerus was the most common cause of the ischemic contracture. When considering individual injuries, supracondylar fractures were reported to be the major cause of ischemic contractures in studies by Reigstad et al. 6, Tsuge 7, Eichler 8, and Ultee 9. Fractures of the forearm bones were found to be the most common cause in a study performed by Chuang et al. 10, in which strategies for preventing Volkmann’s ischemic contracture were evaluated. Other rare causes mentioned in the literature 10 include intoxication, infusion of hypertonic dextrose extravenously, chemotherapy perfusion for therapy of malignant cancers, and following excision of congenital radioulnar synostosis.

Congenital Volkmann ischemic contracture

Congenital Volkmann ischemic contracture, also known as neonatal compartment syndrome, is a very rare condition 11. In this age group there are only about 50 documented cases, all affecting an upper limb, even though it may occur in the lower limbs 12.

The lesions are present at birth and characterised as bullae that quickly burst into deep ulcers evolving to necrotic areas 13. Later, muscular atrophy becomes evident with contraction and flexing of the fingers and claw-like hand position 14. This contraction is due to fibrosis and contracture of the flexing muscle, presenting at birth or developing during the first weeks 15. The histological characteristics are unspecified and the necrosis severity is related to ischemia duration 14. In the cases previously described, there is no evidence of compression in other anatomical regions 16. However, in the present case a few discreet skin lesions were detected in other regions that may be related to slight compression from conflict of intrauterine compartment 11. The haemorrhagic cerebral lesion observed in the magnetic resonance was probably due to traumatic delivery. There is only one reported case of a preterm neonate with concomitant cerebral lesions due to vascular obliteration of the sylvian artery, probably due to vascular emboli consecutive to the death of a co-twin during pregnancy 17.

The specific cause for congenital Volkmann ischemic contracture is still unknown, but is consensual that the ischemic lesion is caused by an increase in intracompartmental pressure 18. The average diastolic pressure of the newborn is approximately 40 mm Hg or less 13. Therefore, even small increases in intracompartmental pressure may rapidly compromise muscular perfusion 13. At this age group, it seems to be the result of external intrauterine compression, for which several situations may be responsible such as instrumental deliveries, difficult extractions, foetopelvic incompatibility, inadequate limb positioning, oligohydramnios, amniotic band or umbilical cord constriction and twin pregnancy 18. Other factors that may lead to difficult extractions and initial intrauterine injury are mother’s diabetes, prolonged membrane rupture, pre-eclampsia, premature birth, uterine anomaly and excessive weight gain on the mother 18. The administration of psychotropic medication during pregnancy, such as narcoleptics and benzodiazepines, has been considered as a risk towards foetal hypomotility and abnormal intrauterine positioning 12. Intrinsic factors to the newborn include hypercoagulability states 13. However, some studies show that there is a predominant involvement of the extensor muscles, a superficial muscular group, which is suggestive that the initial injury is due to external direct compression instead of vascular alterations 19. Even though there may be some associated factors, there are reported cases in which both pregnancy and delivery presented with none of the above related factors 13. Side effects of oseltamivir use during pregnancy are poorly documented, rendering it hard to evaluate its implication, but it seems not to be involved 20.

When the lesions are recent, ideally during the first 24 hour, fasciotomy is the choice treatment as it allows a reduction in intracompartmental pressure and arterial reperfusion 21. However, this diagnosis is rarely taken in consideration immediately. In a study of 24 cases, fasciotomy during the first 24 hour was limited to a single occurrence, the only one to evolve with no complications 13. At a later stage, other surgical treatments are needed including devitalised tissue debridement and skin grafting, nerve decompression, scar revision, contractures release and angular deformity correction 13. The timing of these procedures depends on age, limb size and surgical goals 13.

Volkmann’s ischemic contracture symptoms

Symptoms of Volkmann’s contracture affect the forearm, wrist, and hand. Symptoms may include:

- Decreased sensation

- Paleness of the skin

- Muscle weakness and loss (atrophy)

- Deformity of the wrist, hand, and fingers that causes the hand to have a claw-like appearance

Volkmann’s contracture complications

Untreated, Volkmann’s contracture results in partial or complete loss of function of the arm and hand.

Volkmann’s contracture diagnosis

Your health care provider will perform a physical exam, focusing on the affected arm. If your doctor suspects Volkmann’s contracture, detailed questions will be asked about past injury or conditions that affected the arm.

Tests that may done include:

- X-ray of the arm

- Tests of the muscles and nerves to check their function

Volkmann’s contracture treatment

The goal of treatment is to help people regain some or full use of the arm and hand. Volkmann’s contracture treatment depends on the severity of the contracture 22:

- For mild contracture, muscle stretching exercises and splinting the affected fingers may be done. Surgery may be needed to make the tendons longer.

- For moderate contracture, surgery is done to repair the muscles, tendons, and nerves. If needed, the arm bones are shortened.

- For severe contracture, surgery is done to remove muscles, tendons, or nerves that are thickened, scarred, or dead. These are replaced by muscles, tendons, or nerves transferred from other body areas. Tendons that are still working may need to be made longer.

Up to now, a variety of therapeutic techniques for Volkmann’s contracture, such as splinting 23, excision of the affected muscle 24, muscle sliding 25, tendon lengthening 26 and free muscle transplantation 27, have been reported.

Tension-reduced early mobilization is one of the rehabilitation methods usually applied following tendon rupture reconstruction 28. In this method, the distal stump of the ruptured tendon is transferred to the tendon to the adjacent finger. Afterward, if the ruptured tendon is the flexor tendon, the tension-reduced position is maintained by taping the affected finger to the volar side of the adjacent finger, and the immediate active motion of the fingers is allowed. Using this method, active finger range of motion (ROM) exercise can be performed under a tension-reduced condition of the tendon suture site. Good clinical results have been reported using this method 28.

Concerning the timing of surgery, Seddon 29 recommended waiting for at least 3 months for evidence of spontaneous recovery in the forearm muscles before surgical treatment. Tsuge 30 recommended waiting for more than 5 or 6 months as function of the hand and fingers was gradually restored with the recovery of the degenerated muscles. However, Chuang 31 advocated exploration within 3 weeks of injury, since debridement of infarcted muscles can prevent the fibrotic compression responsible for further nerve damage.

Volkmann’s contracture prognosis

How well a person does depends on the severity and stage of Volkmann ischemic contracture at the time treatment is started.

Outcome is usually good for people with mild contracture. They may regain normal function of their arm and hand. People with moderate or severe contracture who need major surgery may not regain full function.

References- L M, Kiran K K, Kc V, Prasad R S. Volkmann’s Ischemic Contracture with Atrophic Non-union of Ulna Managed by Bone Shortening and Transposition of Radial Autograft. J Orthop Case Rep. 2015;5(1):65–68. doi:10.13107/jocr.2250-0685.259 https://www.ncbi.nlm.nih.gov/pmc/articles/PMC4719359

- Yamaguchi S, Viegas SF. Causes of upper extremity compartment syndrome. Hand Clin. 1998;14:365–370.

- Seddon HJ. Volkmann’s contracture: treatment by excision of the infarct. J Bone Joint Surg. 1956;32B:152–174.

- Kaji Y, Nakamura O, Yamaguchi K, Tobiume S, Yamamoto T. Localized type Volkmann’s contracture treated with tendon transfer and tension-reduced early mobilization: A case report. Medicine (Baltimore). 2017;96(1):e5807. doi:10.1097/MD.0000000000005807 https://www.ncbi.nlm.nih.gov/pmc/articles/PMC5228695

- Sundararaj GD, Mani K (1985) Pattern of contracture and recovery following ischaemia of the upper limb. J Hand Surg Br 10:155–161.

- Reigstad A, Hellum C. Volkmann’s ischaemic contracture of the forearm. Injury. 1980;12:148–150. doi: 10.1016/0020-1383(80)90140-0

- Tsuge K. Management of established Volkmann’s contracture. J Bone Joint Surg. 1975;57A:925–929.

- Eichler GR, Lipscomb PR. The changing treatment of Volkmann’s ischemic contractures from 1955 to 1965 at the Mayo clinic. Clin Orthop. 1967;50:215. doi: 10.1097/00003086-196701000-00022

- Ultee J, Hovius SER. Functional results after treatment of Volkmann’s ischemic contracture: a long-term followup study. Clin Orthop. 2005;431:42–49. doi: 10.1097/01.blo.0000154476.00181.3b

- Chuang DC, Carver N, Wei FC. A new strategy to prevent the sequlae of severe Volkmann’s ischeamia. Plast Reconstr Surg. 1996;98:1023–1031. doi: 10.1097/00006534-199611000-00015

- Rios M, Ribeiro C, Soares P, et al. Volkmann ischemic contracture in a newborn. BMJ Case Rep. 2011;2011:bcr0520114201. Published 2011 Sep 26. doi:10.1136/bcr.05.2011.4201 https://www.ncbi.nlm.nih.gov/pmc/articles/PMC3185372

- Dandurand M, Michel B, Fabre C, et al. [Neonatal Volkmann’s syndrome]. Ann Dermatol Venereol 2009;136:785–9.

- Ragland R, 3rd, Moukoko D, Ezaki M, et al. Forearm compartment syndrome in the newborn: report of 24 cases. J Hand Surg Am 2005;30:997–1003.

- Cham PM, Drolet BA, Segura AD, et al. Congenital Volkmann ischaemic contracture: a case report and review. Br J Dermatol 2004;150:357–63.

- Caoutte-Laberge L, Bortoluzzi P, Egerszegi EP, et al. Neonatal Volkmann’s isquemic contracture of the forearm: a report of five cases. Plast Reconstr Surg 1992;90:621–8.

- Raimer L, McCarthy RA, Raimer D, et al. Congenital Volkmann ischemic contracture: a case report. Pediatr Dermatol 2008;25:352–4.

- Léauté-Labrèze C, Depaire-Duclos F, Sarlangue J, et al. Congenital cutaneous defects as complications in surviving co-twins. Aplasia cutis congenita and neonatal volkmann ischemic contracture of the forearm. Arch Dermatol 1998;134:1121–4.

- Allen LM, Benacci JC, Trane RN, 3rd, et al. A case of neonatal compartment syndrome: importance of early diagnosis in a rare and debilitating condition. Am J Perinatol 2010;27:103–6.

- Tsujino A, Hooper G. Neonatal compression ischaemia of the forearm. J Hand Surg Br 1997;22:612–4.

- Montané E, Lecumberri J, Pedro-Botet ML. [Influenza A, pregnancy and neuraminidase inhibitors]. Med Clin (Barc) 2011;136:688–93.

- Goubier JN, Romaña C, Molina V. [Neonatal Volkmann’s compartment syndrome. A report of two cases]. Chir Main 2005;24:45–7.

- Tsuge K. Treatment of established Volkmann’s contracture. J Bone Joint Surg Am 1975;57:925–9.

- Sundararaj GD, Mani K. Management of Volkmann’s ischaemic contracture of the upper limb. J Hand Surg Br 1985;10:401–3.

- Hovius SE, Ultee J. Volkmann’s ischemic contracture. Prevention and treatment. Hand Clin 2000;16:647–57.

- Sharma P, Swamy MKS. Results of the Max Page muscle sliding operation for the treatment of Volkmann’s contracture of the forearm. J Orthop Traumatol 2012;13:189–96.

- Hardwicke J, Srivastava S. Volkmann’s contracture of the forearm owing to an insect bite: a case report and review of the literature. Ann R Coll Surg Engl 2013;95:e36–7.

- Zuker RM, Bezuhly M, Manktelow RT. Selective fascicular coaptation of free functioning gracilis transfer for restoration of independent thumb and finger flexion following Volkmann ischemic contracture. J Reconstr Microsurg 2011;27:439–44.

- Suzuki T, Iwamoto T, Ikegami H, et al. Comparison of surgical treatments for triple extensor tendon ruptures in rheumatoid hands: a retrospective study of 48 cases. Mod Rheumatol 2016;26:206–10.

- Seddon HJ. Volkmann’s contracture: treatment by excision of the infarct. J Bone Joint Surg Br 1956;38:152–74.

- Tsuge K. Green’s Operative Hand Surgery, Vol. 1. 3rd ed.1993;Philadelphia, PA:Churchill Livingstone, 593-605.

- Chuang DC, Carver N, Wei FC. A new strategy to prevent the sequelae of severe Volkmann’s ischemia. Plast Reconstr Surg 1996;98:1023–31.