Leukoderma

Leukoderma also called leucoderma or achromoderma, is the name given to white patches due to loss of skin color on the skin. These patches are due to the partial or total loss of skin pigmentation or depigmentation.

Leukoderma are very common in both children and adults, seen in at least 1 out of 20 people 1. The prevalence of various hypomelanotic conditions depends on patient demographics (age, sex, race), geography, family history, and exposure to environmental factors. For example, Pityriasis alba is more prevalent (90%) in the pediatric age group (<16 years), Pityriasis versicolor more prevalent in adolescents and young adults, idiopathic guttate melanosis is more prevalent (80% to 87%) in the adult age group (> 40 years), and vitiligo can affect anyone from a toddler to elderly people 2. Pityriasis alba shows slight male predominance, whereas Pityriasis versicolor affects both sexes equally. Pityriasis alba is often seen in patients with a family history of atopic dermatitis, whereas Pityriasis versicolor is more prevalent in the adolescent age group, warm and humid conditions, and lesions are predominantly distributed in seborrheic areas (trunk, neck, and arms) 3. Idiopathic guttate melanosis is more prevalent in the elderly and is hinted by a history of chronic exposure to sunlight and repetitive microtrauma. Lesions usually do not coalesce.

Hansen’s disease (leprosy) is more prevalent in developing countries; more than 75% of leprosy cases in the United States are contributed by immigrants.

Syphilitic leukoderma or leukoderma syphiliticum is a term applied to the depigmented areas, which are most frequently seen on the neck and shoulders 4. Syphilitic leukoderma is found in both fresh and recurrent secondary syphilis and is characterized by the appearance of colorless spots on the side, back and front surfaces of the neck (“Venus necklace”). Syphilitic leukoderma typically appear during the healing stage of secondary syphilis 5. Treponemes have been identified in leukoderma syphiliticum by electron microscopy 6, and in cutaneous gummas by direct immunofluorescence 7, immunohistochemistry 8, and PCR 9. Basal cell and squamous cell carcinomas have been reported to arise in longstanding or healed gumma 10, underscoring the role of chronic inflammation and scarring in the progression to cancer.

It is important to differentiate these conditions because the management and prognosis vary. Complete history (family history and any history of autoimmune diseases), physical examination, and areas of distribution of hypopigmented patches help in determining the right diagnosis. Dermoscopy can aid in differentiating vitiligo from other vitiligo-like conditions. Vitiligo patches usually show residual perifollicular pigmentation, which is absent in other conditions. Vitiligo, at times, could be confused with chemical leukoderma and vitiligo-like depigmentation in oncology patients treated with immunotherapy for non-melanoma metastatic cancers 11.

Figure 1. Syphilitic leukoderma (“Venus necklace”)

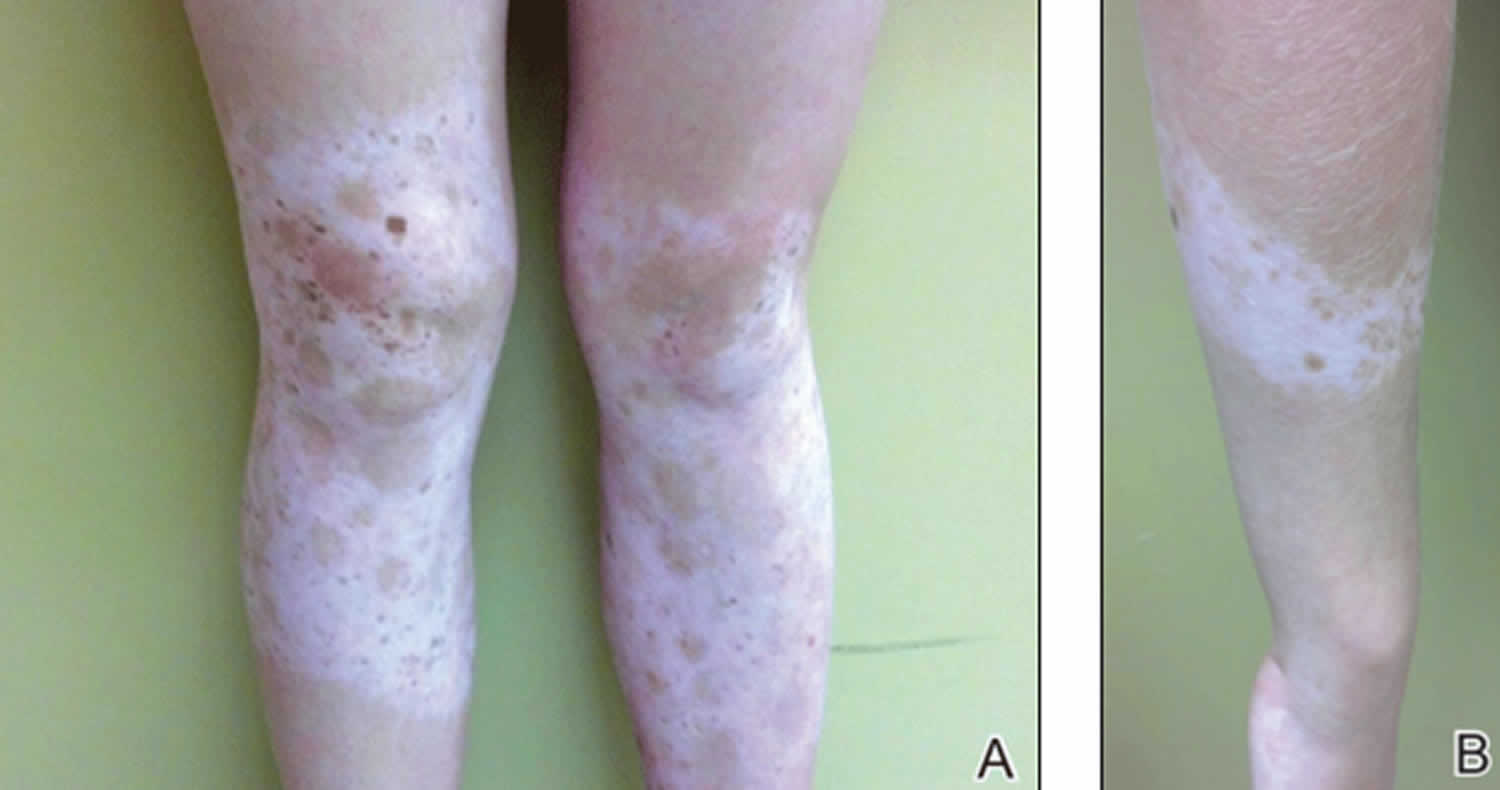

Figure 2. Congenital leukoderma (diagnosed with Piebaldism)

Footnote: A 14-year-old adolescent girl presented with multiple asymptomatic light-colored patches on the forehead, bilateral arms, and legs that had been present since birth. The patient reported that the size of the patches had increased in proportion to her overall growth and that “brown spots” had gradually started to form within and around the patches. She noted that her father and paternal grandfather also had similar clinical findings. A review of systems was negative for hearing impairment, ocular abnormalities, and recurrent infections.

Chemical leukoderma

Chemical leukoderma also known as contact leukoderma, denotes an acquired hypopigmentation caused by repeated exposure to specific chemical compounds (e.g., lead-based cosmetics, skin bleaching agents like hydroquinone, etc) known to destroy the skin pigment cells (melanocytes) 12. Chemical leukoderma is usually due to chemicals found in the workplace, but it can also follow the use of certain cosmetic products. Phenolic and catecholic derivatives are well-documented causes of leukoderma 13. They are commonly found in oral and topical medications, cosmetics, and a variety of nonmedicinal compounds 14.

Chemical leukoderma may develop in the setting of pre-existing idiopathic vitiligo, suggesting a genetic predisposition. This genetic susceptibility may explain why only some people will get leukoderma upon contact with certain chemicals. Liver and thyroid disease have been reported in some patients. However, in the majority of patients, there is neither a personal nor family history of vitiligo nor another autoimmune disease.

The main chemicals that have been known to cause chemical leukoderma include aromatic or aliphatic derivatives of phenols and catechols. Monobenzylether of hydroquinone (MBH) was the first identified chemical to cause leukoderma in leather manufacturing workers who wore rubber gloves cured with monobenzylether of hydroquinone. Other chemicals that are known to cause occupational leukoderma include the phenolic compounds, para-tertiary butylphenol, para-tertiary octylphenol and para-tertiary butylphenolformaldehyde.

The most common cause of chemical leukoderma from cosmetics is para-phenylenediamine in hair dyes. The hair dye may have been used by the patient, or they may have applied it to someone else. As para-phenylenediamine can also be found in black socks and footwear, the leukoderma may also affect the feet. Sensitization to para-phenylenediamine may have followed the application of a temporary black henna tattoo, also leaving a white mark. Frequent use of hair dye has also been associated with an increased risk of developing vitiligo.

Chemical leukoderma due to the azo dyes has been reported with the use of facial cosmetics in the following products:

- Lipsticks

- Lipliner

- Eyeliners.

Chemical leukoderma can also be caused by para-tertiary butyl-phenol (PTBP) in deodorants and spray-on perfumes.

A series of cases followed the use of skin lightening cream containing monobenzylether of hydroquinone on the hands. Monobenzylether of hydroquinone has also been deliberately applied to pigmented areas to reduce the unsightliness of extensive vitiligo.

A skin lightening cream containing rhododendrol (another phenolic compound) resulted in localized chemical leukoderma and widespread vitiligo in about 18,000 users in Japan in 2013. Rhododenol was withdrawn from the market due to rhododendrol-induced leukoderma 15.

Methylphenidate patches (used to treat attention-deficit/hyperactivity disorder) may rarely cause permanent loss of skin colour at the site of application.

Also, it has been reported with cultural practices, particularly in India, related to the use of alta, an azo dye painted on the feet. The specific azo dye identified in alta was solvent yellow 3. chemical leukoderma has also been reported in Asian women with an adhesive bindi, the coloured spot applied to the forehead. The chemical associated with bindi leukoderma is para-tertiary butyl-phenol (PTBP) in the adhesive.

Figure 3. Chemical leukoderma

Footnote: A 78-year-old, African-American woman presented with newly acquired depigmented areas on the perinasal and perioral skin. The patient was blind, but caretakers noticed the change shortly after she applied Vicks VapoRub to her upper and lower cutaneous lip as well as on and around her nose for several consecutive days. She denied irritation or pruritus of the area, and there was no report of precipitating erythema or eczematous-type reaction in the depigmented areas.

[Source 16 ]Chemical leukoderma signs and symptoms

Chemical leukoderma presents as a white patch(es) of skin, initially at the site(s) of application but can spread beyond the area of known contact in approximately one-quarter of patients. A single lesion occurs in approximately one-third of patients; multiple patches are more common.

Chemical leukoderma is never present at birth.

Chemical leukoderma due to cosmetics occurs most frequently on the face. The eyelids are particularly involved. chemical leukoderma due to hair dyes applied to the patient usually affects the hair margin rather than the scalp skin. It can subsequently lead to white patches in distant sites (vitiligo.

Typically there are small confetti-sized flat spots of white skin with a sharply defined margin seen under magnification. The skin is not scaly.

Wood lamp examination shows an accentuation of the pigment loss although this is not always as clear as in vitiligo.

Preceding contact allergic dermatitis does not occur in the majority of cases. However, an itch is reported more commonly with chemical leukoderma than with vitiligo.

Chemical leukoderma diagnosis

Chemical leukoderma must be distinguished from vitiligo. This can sometimes be difficult as both show the same features on histology of a skin biopsy with loss of melanocytes and melanin.

Listed below is suggested diagnostic criteria for chemical leukoderma 17. A patient should have three of the four criteria.

- Acquired vitiligo-like depigmented lesions

- History of repeated exposure to specific chemicals

- A pattern of flat vitiligo-like macules at the site of exposure to the chemical

- Confetti macules

Patch testing with the cosmetic product and the specific allergen may result in new patches of chemical leukoderma and is not recommended.

Chemical leukoderma treatment

Avoidance of the cosmetic product results in the recovery of skin color in the majority of cases, particularly if there was no history of pre-existing vitiligo. However, further extension of the leukoderma has been reported despite strict avoidance of the chemical and this may indicate a genetic tendency to vitiligo. Topical and systemic corticosteroids have been reported to speed the recovery of skin colour. Narrow-band ultraviolet B phototherapy and psoralen ultraviolet A (PUVA) photochemotherapy may also be used in some cases.

Idiopathic guttate hypomelanosis

Idiopathic guttate hypomelanosis also known as leukopathia symmetrica progressiva, is an acquired, benign leukoderma of unknown cause, that is characterized by multiple, discrete, well-circumscribed, smooth-surfaced, round to oval, small, porcelain-white macules, predominantly on the shins and forearms (Figure 4) 18. Idiopathic guttate hypomelanosis is most commonly a complaint of middle-aged, light-skinned women, but it is increasingly seen in both sexes and older dark-skinned people with a history of long-term sun exposure. Typically, idiopathic guttate hypomelanosis develops first on the legs of fair-skinned women in early adult life. Later, it may spread to other sun-exposed areas, such as the arms and the upper part of the back. The face is inexplicably not involved early in idiopathic guttate hypomelanosis. A familial tendency to develop idiopathic guttate hypomelanosis has been noted 19.

Idiopathic guttate hypomelanosis is a benign condition. The cause is not known, but it appears to be related to the effect of the sun on melanocytes, which makes them effete.

A variety of therapeutic methods, including topical steroids, topical retinoids, dermabrasion, cryotherapy, and minigrafting, have been used for idiopathic guttate hypomelanosis with variable success 20. One report describes successful treatment with pimecrolimus 1% 21; however, caution is warranted because the author has anecdotal experience possibly suggesting that topical calcineurin inhibitors may be linked to the development of idiopathic guttate hypomelanosis in immunosuppressed patients. Another described successful treatment with topical tacrolimus, but results were not statistically significant after clinical assessments 22.

Surgical techniques, from cryosurgery to dermabrasion, have been tried for idiopathic guttate hypomelanosis, with some success 20. Theoretically, cryotherapy would remove the damaged melanocytes, which would encourage normal melanocytes to replace them. A randomized, controlled, evaluator-blinded study of 101 lesions treated with a single 5-second tip cryotherapy treatment demonstrated 82.3% of the lesions improved by 75% at 4 months 23. Fractional carbon dioxide laser and nonablative fractional photothermolysis treatment have been reported as safe and effective 24. Excimer laser also may be safe and effective using the vitiligo protocol 25. The use of a spot 88% phenol peel is another option; however, persistent scabbing and hyperpigmentation are potential adverse effects 26.

Figure 4. Guttate leukoderma

Leukoderma causes

There are many causes of leukoderma, some of which include:

Chemical leukoderma

- Exposure to depigmentation agents, such as p-tertiary butyl phenol

- Leukoderma occurs on the exposed parts of the body, but other areas not necessarily in contact with the chemicals may also be affected

- Depigmented areas may continue to arise even after the patient is no longer in contact with the chemicals

- Repigmentation may or may not occur

Congenital leukoderma

- Tuberous sclerosis (Ash leaf spots in tuberous sclerosis)

- Partial albinism

- Piebaldism and Waardenburg syndrome

- Nevus depigmentosus

Immunological leukoderma

- Vitiligo

- Melanoma-associated vitiligo or leukoderma

- Halo nevus

- Hypopigmented sarcoidosis

Post-inflammatory leukoderma

- Inflammatory skin diseases

- Allergic contact dermatitis

- Atopic dermatitis

- Chronic graft versus host reaction

- Cutaneous lupus erythematosus

- Dermatitis (eczema)

- Discoid lupus erythematosus

- Insect‐bite reactions

- Lichen planus

- Lichen sclerosus

- Lichen striatus

- Lymphomatoid papulosis

- Pityriasis lichenoides chronica

- Psoriasis

- Sarcoidosis

- Scleroderma

- Stevens–Johnson syndrome

- Infections

- Chickenpox

- Herpes zoster

- Impetigo

- Onchocerciasis

- Pinta

- Pityriasis versicolor

- Syphilis

- Procedure‐related

- Chemical peels

- Cryotherapy

- Dermabrasion

- Laser

- Miscellaneous

- Thermal burns

Postinflammatory hypopigmentation is an acquired partial or total loss of skin pigmentation occurring after cutaneous inflammation 27. The distribution and severity of pigment loss is related to the extent and degree of the inflammation. Post-inflammatory leukoderma is a common cause of acquired hypopigmentary skin disorders. Post-inflammatory leukoderma can be a result of cutaneous inflammation, injury or dermatological treatment. Post-inflammatory leukoderma can be secondary to any cutaneous inflammatory conditions (eg., pityriasis lichenoides chronica, lichen striatus, atopic dermatitis), infections (eg., Tinea versicolor, Herpes Zoster, Syphilis), procedures (eg., cryotherapy, dermabrasion) and miscellaneous causes (eg., burns) 27. Most cases of postinflammatory hypopigmentation improve spontaneously within weeks or months if the primary cause is ceased; however, it can be permanent if there is complete destruction of melanocytes 27.

Infectious leukoderma

- Pityriasis versicolor (Malassezia fungus)

- Leprosy (Mycobacterium leprae bacteria)

- Lichen planus

- Syphilis or Leukoderma syphiliticum (Treponema pallidum bacteria)

- Progressive macular hypomelanosis (bacterial infection by Propionibacterium acne)

- Protozoal by post-kala-azar dermal leishmaniasis

- Eruptive hypomelanosis (postviral exanthem)

Drugs leukoderma

- EGFR inhibitors

- Immune checkpoint inhibitors (pembrolizumab, nivolumab)

- Intralesional steroid injections

- Methylphenidate transdermal patch

Other leukoderma

- Cutaneous T-cell lymphoma e.g., mycosis fungoides, tumor of follicular infundibulum. Diagnosing hypopigmented mycosis fungoides is usually delayed in children (although it is rare), as it is often mistaken with other hypomelanosis conditions like Pityriasis, eczema, vitiligo, progressive macular hypomelanosis, etc. A high rate of suspicion and skin biopsy is required for accurate diagnosis of hypopigmented mycosis fungoides, and tumor of follicular infundibulum 28.

- Alopecia mucinosa

- Normal aging- Idiopathic guttate melanosis

- Nutritional deficiencies- Kwashiorkor (a severe protein malnutrition condition), vitamin B12 deficiency, copper and iron deficiency

- Inflammatory causes- Pityriasis alba (association with atopic dermatitis)

- Vascular causes (venous congestion)- Bier’s spots

Leukoderma pathophysiology

The pathogenic mechanism is different in various conditions associated with leukoderma. Pathophysiology for a few are discussed below:

- Pityriasis alba – There is no proven cause identified. Most studies suggest that UV light exposure has a causal relationship. UV radiation affects the function of active melanocytes, thereby altering the synthesis of melanin.

- Pityriasis versicolor or Tinea versicolor – Malassezia is a common commensal of healthy skin transforms into a pathogenic (filamentous) form. Factors that contribute to pathogenic conversion are genetic predisposition, environment conditions (heat, humidity), oily skin, and application of oily creams or lotions 3. The pathogenic form metabolizes fatty acids on the skin, release azelaic acid and other metabolites. Azelaic acid inhibits the dopa-tyrosinase enzyme, which is the rate-limiting enzyme for melanin synthesis, thereby causing hypopigmentation skin lesions.

- Idiopathic guttate hypomelanosis – The predominant involvement of sun-exposed areas in idiopathic guttate hypomelanosis raises suspicion of UV light as a primary factor affecting melanin synthesis. Few studies also suggest that idiopathic guttate hypomelanosis has a positive association with HLA DQ3, repeated microtrauma, and autoimmunity 29. Histopathologic correlation like structural abnormalities of melanocytes, defective keratinocyte uptake, and decrease melanosomes help to understand the pathogenic mechanisms involved in developing hypopigmented macules in idiopathic guttate hypomelanosis 30.

- Vitiligo – Multiple pathogenic mechanisms were proposed. T cell-induced melanocyte apoptosis, autoantibodies to components of melanocytes leads to decreased melanin production and thereby causing hypopigmentation.

- Albinism – Albinism is an autosomal recessive disease, associated with a deficiency of tyrosinase enzyme (the rate-limiting enzyme in melanin synthesis). The severity of clinical features depend on the mutation involved 31.

- Halo nevus – Based on histopathological findings, the abundance of Langerhans cells in the area of the lesion is responsible for hypopigmentation. Halo nevus is benign. Some also argue that the halo nevus condition has an association with vitiligo 31.

- Post-inflammatory hypopigmentation – This condition is associated with trauma or exposure to chemicals (cleaning agents, chemicals used to remove tattoos, or for cosmetic purposes). The pathogenesis in this condition is related to melanocyte injury resulting in decreased melanin, which in turn causes hypopigmented or depigmented patches. Post-inflammatory conditions can also be associated with hyperpigmentation.

- Ash leaf spots – These are the cutaneous findings associated with the neurocutaneous disorder. The presence of three or more ash leaf spots should raise suspicion of tuberous sclerosis.

Leukoderma complications

- Malignancy – Most of the leukoderma lack melanin in the affected area, thereby more prone to the harmful effects of UV radiation on keratinocytes and melanocytes. This renders them more susceptible to skin cancers than the general population. Patients are advised to minimize sun exposure and use sunscreen.

- Systemic disorder – Diagnosing the underlying root cause is important to treat the disease condition promptly and to improve the overall health rather than just treating hypomelanosis. For example, the presence of ash leaf spots indicates the possibility of neurocutaneous disorder (tuberous sclerosis).

- Psychological impact – This includes anxiety, stress, or depression that could affect an individual with hypopigmented skin lesions.

Leukoderma diagnosis

The differentiation of various hypopigmented skin conditions is not always possible solely based on the clinical findings of the lesion. A detailed history of the patient, including personal, occupational, and family history, gives a clue about the cause and severity (inherited/ acquired, benign/malignant) of the condition. The patients, at times, may have extracutaneous signs and symptoms, and a complete physical examination from head to toe is vital to make the right diagnosis.

The following questionnaire and examination findings may be useful to evaluate the patients with leukoderma:

- Is the skin lesion present since birth or acquired?

- If acquired, is it sudden or gradual in onset?

- Any history of prior inflammation, or exposure to chemical substances?

- Is the hypopigmentation localized or diffuse?

- Location of the lesions – which areas are predominantly affected? (sun-exposed areas, or body-folds like axilla, or under the breast)

- Characters of lesion – this includes:

- Size of the lesions

- Margins-well circumscribed or ill-defined

- Appearance- scaly/non-scaly

- Pattern of distribution

- Unilateral or bilateral

- Stable or progressive

- Any coalesce of lesions

- Any changes in color

- Any history of pruritus or signs of excoriation

- Any history of prior inflammation, or exposure to chemical substances?

- Any change in the characteristics of lesions due to weather conditions?

- Surrounding skin characteristics.

A systematic approach should be followed to reach the right diagnosis.

- Wood’s lamp examination – This is used for better visualization of skin lesions to differentiate pigment abnormalities (especially hypopigmented lesions from depigmented lesions). This is done in a darkened room using a Wood’s lamp that emits long-wave UVA (Ultraviolet light A) with a wavelength of approximately 365 nm 32. The light source should be held at 4 to 5 inches away from the skin surface. Normal skin does not fluoresce. Depigmented lesions (eg., vitiligo) and hypopigmented lesions with decreased melanin production are markedly enhanced, appear bright white whereas, hypopigmented lesions with normal melanin (idiopathic guttate hypomelanosis, progressive macular hypomelanosis) are not accentuated. A few of the characteristic features of Wood’s lamp examination are orange fluorescence in Pityriasis versicolor, red fluorescence localized to follicles in progressive macular hypomelanosis, bright blue-white fluorescence in Vitiligo, etc 33. Wood’s lamp is also used to perform a meticulous search for the presence of more hypopigmented lesions when a patient presents with a single lesion 34.

- Dermatoscopy – This refers to the skin examination using a skin surface microscope, especially used to evaluate pigment abnormalities of the skin. Dermoscopic findings give details about- nature of pigmentation, edges of the lesion (well-defined/ ill-defined), the appearance of lesions (scaly/ non-scaly), perifollicular hyperpigmentation (seen in Vitiligo), presence of telangiectasia, and characteristics of the surrounding skin 35.

- Potassium hydroxide (KOH) mount of skin scrapings – Potassium hydroxide test is useful to quickly identify fungal infections like Tinea versicolor (Spaghetti and meatball appearance of hyphae) in outpatient settings. The specimen is prepared by adding one drop of 10% potassium hydroxide to skin scrapings and examining it under the microscope 36.

- Skin Biopsy – Although skin biopsy gives accurate diagnosis in most conditions, this is not routinely performed; it is used only when the diagnosis is unclear or suspecting infectious causes like leprosy, sarcoidosis, or underlying malignancy. Tissue biopsy is processed and studied under a microscope using various stains like hematoxyline and eosin, Fontana Masson, or Melanin-A stains. Immunofluorescence studies on the specimen could be performed for the presence of antibodies, and infiltration of lymphocytes into the epidermis, etc 37.

- Electron Microscopy – This is not commonly available in clinical settings, and physicians should rely on other clinical findings. Electron microscopic study of skin lesion gives an insight into ultrastructural details of the lesion and helps differentiate the causes for hypomelanosis. For example, clinical differentiation of ash leaf spots, a common presentation in the pediatric age group from nevus depigmentosus, is challenging even based on histopathologic findings. The findings under electron microscopy show a decrease in melanosome transfer to keratinocytes in nevus depigmentosus, and reduced size and melanization of melanosomes result in the formation of aggregates in keratinocytes in ash leaf spots 38.

Histopathology

Histopathological findings are occasionally required for diagnosis. They are useful in evaluating the underlying pathophysiology to determine the right diagnosis. It gives an overview of the presence of melanin, melanocytes, changes in epidermal cells like acanthosis, hyperkeratosis, parakeratosis, epidermotropism, spongiosis, perivascular lymphocytic infiltrate, etc. A few of the classic histopathologic features of hypomelanotic conditions are spaghetti meatball appearance in Tinea versicolor, pautrier microabscesses in hypopigmented mycosis fungoides, absence of melanocytes in vitiligo, decrease in DOPA positive melanocytes (active melanocytes) in idiopathic guttate melanosis, dilated follicular infundibula connected to each and to the overlying epidermis in the tumor of the follicular infundibulum (infundibulomatosis), and many more. Histopathological findings are also useful to determine the status of the disease, e.g., active or inactive stage of vitiligo 39. Immunohistochemical staining can be used to evaluate the peculiar characteristics of cells (like CD4 and CD8 infiltration) in the epidermis.

Leukoderma treatment

The management of leukoderma depends on the underlying cause. Successful repigmentation is often possible with timely diagnosis, removal of offending agents (chemicals, infectious agents), avoiding exposure to sunlight, using sunscreen, and appropriate therapeutic treatment 2. Repigmentation might not be possible in the congenital or inherited conditions (associated with chromosomal defects). Therapeutic treatment helps to fasten the process of repigmentation. Repigmentation is achieved by medications, phototherapy, and surgical procedures.

Patient should be advised to consult a board certified dermatologist if repigmentation is not achieved with effective treatment, or any suspicion arises of neurocutaneous disorder (tuberous sclerosis), hypopigmented mycosis fungoides, the tumor of follicular infundibulum, or in any doubtful diagnosis.

Medications

There are topical and systemic medications.

- Topical corticosteroids – Low dose corticosteroids are used as first-line drugs in many hypopigmented conditions. They are known to accelerate the repigmentation process. Their use, along with phototherapy, also has great outcomes. Systemic corticosteroids are rarely used to treat hyperpigmentation, for e.g., in vitiligo, to halt the rapid progression of skin lesions.

- Topical calcineurin inhibitors – These are topical immunomodulatory agents (tacrolimus, pimecrolimus), also used as first-line medication. Tacrolimus inhibits the synthesis and release of proinflammatory cytokines, thereby protecting melanocytes from the effects of T-cell and mast-cells. In contrast to topical steroids, tacrolimus does not cause skin atrophy and striae, preferred for treating facial hypomelanosis conditions.

- Vitamin D – The current literature reviews that vitamin D has an association with skin pigmentation. Vitamin D increases melanogenesis by increasing the tyrosinase content in melanocytes by the anti-apoptotic effect 40.

- Antifungals – These are used in treating Tinea versicolor infection, available in both topical and systemic forms. Topical agents are often used for weeks to months; include selenium sulfide shampoo, 1% or 2% ketoconazole ointment, zinc pyrithione. Oral medications like fluconazole, itraconazole are used for a short duration of therapy.

- Oral isotretinoin – Oral isotretinoin is used to treat conditions like progressive macular hypomelanosis in which propionibacterium acne is the underlying cause 33.

- Emollients – Emollients soften skin and moisturisers add moisture. Emollients are used to correct dryness and scaling of the skin and are an effective treatment for mild irritant contact dermatitis.

- Humectants or keratolytics included glycerine, urea and alpha hydroxy acids such as lactic acid or glycolic acid. They increase the water holding capacity of the stratum corneum and they also have a peeling or keratolytic action. Humectant / keratolytics are particularly important in management of the ichthyoses (inherited or acquired scaly disorders of the skin) but urea and lactic acid preparations often sting if applied to scratched, fissured or dermatitic skin.

- Occlusive emollients consist of oils of non-human origin (wool-fat, mineral oil etc.), either in pure form or mixed with varying amounts of water through the action of an emulsifier to form a lotion or cream. A large variety are available, reflecting that there is no ‘right’ moisturiser for all patients; the most suitable one often having to be found by trial and error. The choice of occlusive emollient depends upon the area of the body and the degree of dryness and scaling of the skin. Lotions are used for the scalp and other hairy areas and for mild dryness on the face, trunk and limbs. Creams are suitable for moderate dry skin. Ointments are recommended for very dry scaly areas, but many patients find them too greasy. Sorbolene cream is a good all-round moderate-strength moisturiser that suits many patients because it is non-greasy, cheap and available in bulk with or without prescription. Typically, 250g (or ml) to 1Kg (1L) are needed and liberal and regular usage is to be encouraged.

- Bath oil deposits a thin layer of oil on the skin upon rising from the water.

- Lotions are more occlusive than oils and are best applied immediately after bathing, to retain the water in the skin, and at other times as necessary.

- Creams are more occlusive again. They include sorbolene cream, cetomacrogol cream, fatty cream, oily cream.

- Ointments are the most occlusive, and include emulsifying ointment and white soft paraffin.

- The most occlusive of these are called protectives or barriers and contain dimethicone or similar compounds.

Phototherapy

Phototherapy – Phototherapy includes narrow-band ultraviolet B and psoralen ultraviolet A (PUVA). Narrow-band ultraviolet B is superior and preferred over PUVA in treating vitiligo. PUVA has comparatively more adverse effects because of the systemic use of psoralen. PUVA is contraindicated in children and pregnant women 41.

Surgical procedures

Surgical procedures such as skin grafting, split skin grafting are practiced in treating some localized depigmented and inherited hypopigmented conditions.

Leukoderma prognosis

Most of the conditions associated with leukoderma or hypopigmentation are benign in nature and have an excellent prognosis 2. Often, repigmentation can be achieved with prompt diagnosis and treatment. However, the prognosis is not great in inherited conditions. Prognosis in hypomelanosis associated with underlying malignancy differs with the time of diagnosis, as most of them are mistaken for benign conditions like Pityriasis alba, idiopathic guttate melanosis resulting in delayed treatment 2. Interprofessional team consultation yields a better prognosis in patients affected by hypomelanosis in conjunction with systemic conditions.

References- Hill JP, Batchelor JM. An approach to hypopigmentation. BMJ. 2017 Jan 12;356:i6534. doi: 10.1136/bmj.i6534

- Madireddy S, Crane JS. Hypopigmented Macules. [Updated 2020 Oct 9]. In: StatPearls [Internet]. Treasure Island (FL): StatPearls Publishing; 2020 Jan-. Available from: https://www.ncbi.nlm.nih.gov/books/NBK563245

- Karray M, McKinney WP. Tinea Versicolor. [Updated 2020 Aug 10]. In: StatPearls [Internet]. Treasure Island (FL): StatPearls Publishing; 2020 Jan-. Available from: https://www.ncbi.nlm.nih.gov/books/NBK482500

- Stokes JH. Modern Clinical Syphology. W. B. Saunders Co; 1934.

- Poulsen A, Secher L, Kobayasi T, Weismann K. Treponema pallidum in leukoderma syphiliticum demonstrated by electron microscopy. Acta dermato-venereologica. 1988;68(2):102–106.

- Poulsen A, Kobayasi T, Secher L, Weismann K. Treponema pallidum in human chancre tissue: an electron microscopic survey. Acta dermato-venereologica. 1986;66(5):423–430.

- Handsfield HH, Lukehart SA, Sell S, Norris SJ, Holmes KK. Demonstration of Treponema pallidum in a cutaneous gumma by indirect immunofluorescence. Arch Dermatol. 1983 Aug;119(8):677–680.

- Behrhof W, Springer E, Brauninger W, Kirkpatrick CJ, Weber A. PCR testing for Treponema pallidum in paraffin-embedded skin biopsy specimens: test design and impact on the diagnosis of syphilis. Journal of clinical pathology. 2008 Mar;61(3):390–395.

- Zoechling N, Schluepen EM, Soyer HP, Kerl H, Volkenandt M. Molecular detection of Treponema pallidum in secondary and tertiary syphilis. Br J Dermatol. 1997 May;136(5):683–686.

- Narouz N, Wade AA, Allan PS. Can basal cell carcinoma develop on the site of a healed gumma? International journal of STD & AIDS. 1999 Sep;10(9):623–625.

- Liu RC, Consuegra G, Chou S, Fernandez Peñas P. Vitiligo-like depigmentation in oncology patients treated with immunotherapies for nonmelanoma metastatic cancers. Clin Exp Dermatol. 2019 Aug;44(6):643-646. doi: 10.1111/ced.13867

- Ghosh S. Chemical leukoderma: what’s new on etiopathological and clinical aspects?. Indian J Dermatol. 2010;55(3):255-258. doi:10.4103/0019-5154.70680 https://www.ncbi.nlm.nih.gov/pmc/articles/PMC2965912

- Boissy RE, Manga P. On the etiology of contact/occupational vitiligo. Pigment Cell Res. 2004 Jun;17(3):208-14. https://doi.org/10.1111/j.1600-0749.2004.00130.x

- Svobodová A, Psotová J, Walterová D. Natural phenolics in the prevention of UV-induced skin damage. A review. Biomed Pap Med Fac Univ Palacky Olomouc Czech Repub. 2003 Dec;147(2):137-45.

- Kim M, Lee CS, Lim KM. Rhododenol Activates Melanocytes and Induces Morphological Alteration at Sub-Cytotoxic Levels. Int J Mol Sci. 2019;20(22):5665. Published 2019 Nov 12. doi:10.3390/ijms20225665

- Boyse KE, Zirwas MJ. Chemical Leukoderma Associated with Vicks VapoRub. J Clin Aesthet Dermatol. 2008;1(4):34-35. https://www.ncbi.nlm.nih.gov/pmc/articles/PMC3016932

- Ghosh, S. and Mukhopadhyay, S. (2009), Chemical leucoderma: a clinico‐aetiological study of 864 cases in the perspective of a developing country. British Journal of Dermatology, 160: 40-47. doi:10.1111/j.1365-2133.2008.08815.x

- Ravikiran SP, Sacchidanand S, Leelavathy B. Therapeutic wounding – 88% phenol in idiopathic guttate hypomelanosis. Indian Dermatol Online J. 2014;5(1):14-18.

- Falabella R, Escobar C, Giraldo N, et al. On the pathogenesis of idiopathic guttate hypomelanosis. J Am Acad Dermatol. 1987 Jan. 16(1 Pt 1):35-44.

- Ploysangam T, Dee-Ananlap S, Suvanprakorn P. Treatment of idiopathic guttate hypomelanosis with liquid nitrogen: light and electron microscopic studies. J Am Acad Dermatol. 1990 Oct. 23(4 Pt 1):681-4.

- Asawanonda P, Sutthipong T, Prejawai N. Pimecrolimus for idiopathic guttate hypomelanosis. J Drugs Dermatol. 2010 Mar. 9(3):238-9.

- Rerknimitr P, Disphanurat W, Achariyakul M. Topical tacrolimus significantly promotes repigmentation in idiopathic guttate hypomelanosis: a double-blind, randomized, placebo-controlled study. J Eur Acad Dermatol Venereol. 2013 Apr. 27(4):460-4.

- Laosakul K, Juntongjin P. Efficacy of tip cryotherapy in the treatment of idiopathic guttate hypomelanosis (IGH): a randomized, controlled, evaluator-blinded study. J Dermatolog Treat. 2017 May. 28 (3):271-275.

- Rerknimitr P, Chitvanich S, Pongprutthipan M, Panchaprateep R, Asawanonda P. Non-ablative fractional photothermolysis in treatment of idiopathic guttate hypomelanosis. J Eur Acad Dermatol Venereol. 2014 Oct 10.

- Gordon JR, Reed KE, Sebastian KR, Ahmed AM. Excimer Light Treatment for Idiopathic Guttate Hypomelanosis: A Pilot Study. Dermatol Surg. 2017 Apr. 43 (4):553-557.

- Ravikiran SP, Sacchidanand S, Leelavathy B. Therapeutic wounding – 88% phenol in idiopathic guttate hypomelanosis. Indian Dermatol Online J. 2014 Jan. 5 (1):14-8.

- Vachiramon V, Thadanipon K. Postinflammatory hypopigmentation. Clin Exp Dermatol. 2011 Oct;36(7):708-14. https://doi.org/10.1111/j.1365-2230.2011.04088.x

- Abdolkarimi B, Sepaskhah M, Mokhtari M, Aslani FS, Karimi M. Hypo-pigmented mycosis fungoides is a rare malignancy in pediatrics. Dermatol Online J. 2018 Nov 15;24(11):13030/qt8p63z7n0

- Kim SK, Kim EH, Kang HY, Lee ES, Sohn S, Kim YC. Comprehensive understanding of idiopathic guttate hypomelanosis: clinical and histopathological correlation. Int J Dermatol. 2010 Feb;49(2):162-6. doi: 10.1111/j.1365-4632.2009.04209.x

- Brown F, Crane JS. Idiopathic Guttate Hypomelanosis. [Updated 2020 Sep 20]. In: StatPearls [Internet]. Treasure Island (FL): StatPearls Publishing; 2020 Jan-. Available from: https://www.ncbi.nlm.nih.gov/books/NBK482182

- Brown AE, Qiu CC, Drozd B, Sklover LR, Vickers CM, Hsu S. The color of skin: white diseases of the skin, nails, and mucosa. Clin Dermatol. 2019 Sep-Oct;37(5):561-579. doi: 10.1016/j.clindermatol.2019.07.018

- Alikhan A, Felsten LM, Daly M, Petronic-Rosic V. Vitiligo: a comprehensive overview Part I. Introduction, epidemiology, quality of life, diagnosis, differential diagnosis, associations, histopathology, etiology, and work-up. J Am Acad Dermatol. 2011 Sep;65(3):473-491.

- Saleem MD, Oussedik E, Picardo M, Schoch JJ. Acquired disorders with hypopigmentation: A clinical approach to diagnosis and treatment. J Am Acad Dermatol. 2019 May;80(5):1233-1250.e10. doi: 10.1016/j.jaad.2018.07.070

- Al Aboud DM, Gossman W. Woods Light. [Updated 2020 Aug 15]. In: StatPearls [Internet]. Treasure Island (FL): StatPearls Publishing; 2020 Jan-. Available from: https://www.ncbi.nlm.nih.gov/books/NBK537193

- Al-Refu K. Dermoscopy is a new diagnostic tool in diagnosis of common hypopigmented macular disease: A descriptive study. Dermatol Reports. 2018;11(1):7916. Published 2018 Dec 21. doi:10.4081/dr.2018.7916 https://www.ncbi.nlm.nih.gov/pmc/articles/PMC6509478

- Shalaby MF, El-Din AN, El-Hamd MA. Isolation, Identification, and In Vitro Antifungal Susceptibility Testing of Dermatophytes from Clinical Samples at Sohag University Hospital in Egypt. Electron Physician. 2016 Jun;8(6):2557-67.

- Veitch D, Miller J, Raichura S, McKenna J. Skin biopsy. Br J Hosp Med (Lond). 2018 May 2;79(5):C78-C80. doi: 10.12968/hmed.2018.79.5.C78

- Jindal R, Jain A, Gupta A, Shirazi N. Ash-leaf spots or naevus depigmentosus: a diagnostic challenge. BMJ Case Rep. 2013;2013:bcr2012007008. Published 2013 Jun 10. doi:10.1136/bcr-2012-007008 https://www.ncbi.nlm.nih.gov/pmc/articles/PMC3703063

- Tham HL, Linder KE, Olivry T. Autoimmune diseases affecting skin melanocytes in dogs, cats and horses: vitiligo and the uveodermatological syndrome: a comprehensive review. BMC Vet Res. 2019 Jul 19;15(1):251.

- AlGhamdi K, Kumar A, Moussa N. The role of vitamin D in melanogenesis with an emphasis on vitiligo. Indian J Dermatol Venereol Leprol. 2013 Nov-Dec;79(6):750-8. doi: 10.4103/0378-6323.120720

- Bae JM, Jung HM, Hong BY, et al. Phototherapy for Vitiligo: A Systematic Review and Meta-analysis. JAMA Dermatol. 2017;153(7):666-674. doi:10.1001/jamadermatol.2017.0002 https://www.ncbi.nlm.nih.gov/pmc/articles/PMC5817459