What is microscopic colitis

Microscopic colitis is a long-standing (chronic) inflammation of the colon (large intestine) that a health care provider can see only with a microscope because the tissue may appear normal with colonoscopy or flexible sigmoidoscopy 1, 2. Inflammation is the body’s normal response to injury, irritation, or infection of tissues. Microscopic colitis is a type of inflammatory bowel disease (IBD), the general name for diseases that cause irritation and inflammation in the intestines. Crohn’s disease and ulcerative colitis are other common types of inflammatory bowel disease (IBD). Unlike the other types of inflammatory bowel disease (Crohn’s disease and ulcerative colitis), microscopic colitis does not increase your risk of developing colon cancer 3.

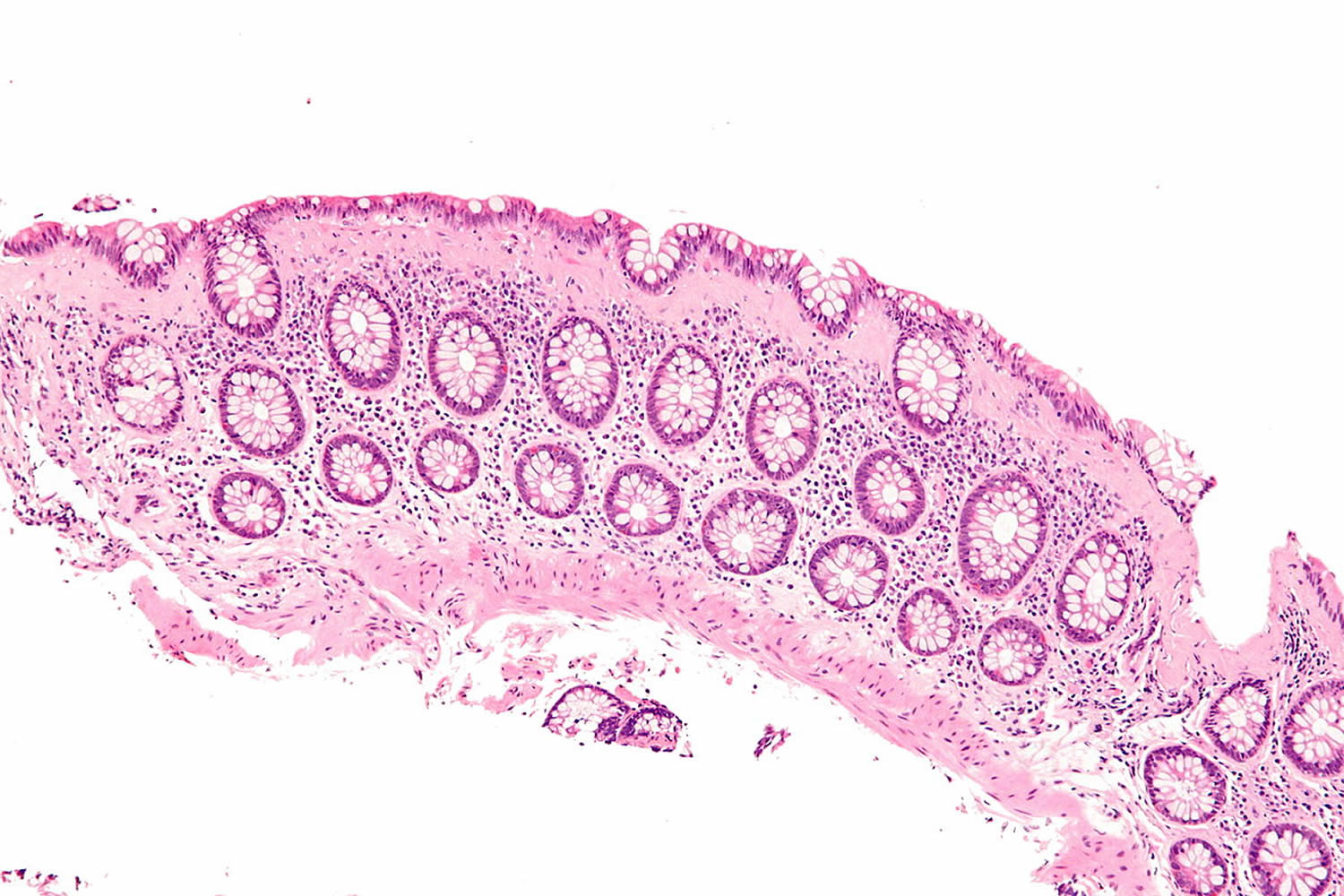

Microscopic colitis is described by a clinicopathological triad characterized by a history of chronic or intermittent watery diarrhea, normal or almost normal endoscopic examination of the colon (e.g., with slight edema, erythema, and/or loss of vascular pattern, although rarely more significant macroscopic changes are reported, including pseudomembranes and ‘cat scratch changes’) 4, as well as a distinct histological pattern when examined under a microscope – hence the name microscopic colitis 5.

Microscopic colitis is divided into two subtypes: collagenous colitis and lymphocytic colitis. The two types cause different changes in colon tissue 6:

- Lymphocytic colitis, the colon lining contains more white blood cells than normal. The layer of collagen under the colon lining is normal or only slightly thicker than normal.

- Collagenous colitis, the layer of collagen under the colon lining is thicker than normal. The colon lining may also contain more white blood cells than normal.

- Incomplete microscopic colitis, in which there are mixed features of collagenous and lymphocytic colitis.

Researchers believe collagenous colitis and lymphocytic colitis may be different phases of the same condition. Symptoms, testing and treatment are the same for all subtypes.

The symptoms of microscopic colitis can come and go frequently. Sometimes the symptoms resolve on their own. If not, your doctor can suggest a number of effective medications.

People are more likely to get microscopic colitis if they:

- are 50 years of age or older

- are female

- have an autoimmune disease

- smoke cigarettes, especially people ages 16 to 44 7

- use medications that have been linked to the disease

Research suggests that, in the United States, about 700,000 people have microscopic colitis 8. A recent French study reported that the incidence of microscopic colitis was 7.9 per 100,000 inhabitants, similar to the incidence of Crohn’s disease in that population 9. Although most patients receive their diagnosis at an age of 60 or above, approximately 25% of patients get diagnosed before the age of 45 10. Microscopic colitis has even been reported in children, which, however, is very rare 11. A female preponderance exists in both collagenous and lymphocytic colitis, with a female-to-male ratio of 3.1 and 1.9, respectively 12, 13.

To help diagnose microscopic colitis, your doctor will ask about your symptoms and medical history and will perform a physical exam. Your doctor may ask about factors that increase the risk of developing microscopic colitis, such as smoking or taking certain medicines.

Your doctor may order medical tests, such as blood and stool tests, to check for signs of conditions that cause symptoms similar to those of microscopic colitis. Conditions that cause similar symptoms include celiac disease, other types of inflammatory bowel disease (IBD), and infections. The diagnosis of microscopic colitis relies on the histological examination of colonic biopsies and requires dedicated gastroenterologists, endoscopists and histopathologists 14.

To treat microscopic colitis, your doctor may recommend 15, 14:

- quitting smoking, if you smoke

- changing any medicines you take that could be causing microscopic colitis or making your symptoms worse

- taking medicines to treat microscopic colitis

- changing what you eat and drink to help improve symptoms

Medicines most often treat microscopic colitis effectively. In rare cases, doctors may recommend surgery.

Table 1. Histological key features of microscopic colitis: collagenous colitis and lymphocytic colitis

| Clinical groups | Morphology subgroups | Increased mononuclear inflammation of lamina propria | Thickness of collagenous band | Number of intraepithelial lymphocytes |

|---|---|---|---|---|

| Microscopic colitis | Collagenous colitis | Increased infiltrate (lymphocytes and plasma cells) with homogenous distribution throughout the colon | Thickening (≥10 μm) | Normal/slightly increased |

| Lymphocytic colitis | Increased infiltrate (lymphocytes and plasma cells) with homogenous distribution throughout the colon | Normal or slightly increased (<10 μm) | >20 intraepithelial lymphocytes per 100 epithelial cells |

Footnote: IELs, intraepithelial lymphocytes.

[Source 16 ]A meta-analysis has revealed a pooled worldwide incidence of microscopic colitis of 4.9 cases per 100,000 patient-years for collagenous colitis and 5.0 cases per 100,000 patient-years for lymphocytic colitis 14. Epidemiological studies have shown that in some countries the incidence of microscopic colitis has exceeded those of Crohn’s disease and ulcerative colitis among elderly persons. For example, in a recent Danish nationwide cohort study, the incidence of microscopic colitis (mean age at the time of diagnosis: 65 years) was 24.3 per 100,000 patient-years in 2016 vs. 18.6 for ulcerative colitis and 9.1 for Crohn’s disease per 100,000 patient-years in 2013 17.

In general, the incidence of microscopic colitis has increased over time 12. Various factors, such as improved recognition of this disorder among gastroenterologists and pathologists, as well as varying presence of risk factors, may influence regional and temporal differences of the incidence.

Established risk factors linked to an increased risk of microscopic colitis include increasing age, with 75% of the people affected being over 50 years old 18. In addition, a history of autoimmune disease 19, for example, celiac disease, type 1 diabetes mellitus, rheumatoid arthritis, polyarthritis, and thyroiditis are linked to an increased risk of microscopic colitis 20, 21, 22. Celiac disease is associated with a 50 to 70 times greater risk of microscopic colitis, especially in middle-aged women, and with severe villous atrophy 23. In a multicenter, prospective study of 433 patients with microscopic colitis or functional diarrhea, Macaigne and colleagues 24 found that microscopic colitis was associated with age over 50 years, nocturnal diarrhea, weight loss, new medications and autoimmune disease.

Bile acid malabsorption is also associated with increased risk of microscopic colitis 25.

Cigarette smoking is another risk factor associated with microscopic colitis 26. The risk appears to be up to five times higher in current smokers, with the disease onset occurring a minimum 10 years earlier compared to nonsmokers 26. Current smoking increases the risk of persistent disease 27 and collagenous colitis diagnosis at a young age 28.

A variety of environmental factors, including a wide range of drugs, have been associated with the pathophysiology of microscopic colitis 29, 30. Thus, a certain cause–effect relationship between drug exposure and microscopic colitis has been described for proton pump inhibitors (PPIs), nonsteroidal anti-inflammatory drugs (NSAIDs), or selective serotonin reuptake inhibitors (SSRIs) both for current and recent use 31, 32. However, when using diarrheal controls instead of healthy controls, the association with several of these medications lessens or resolves 29. The underlying mechanisms are not yet clarified, and these drugs could merely be triggers but not causative of inflammation in predisposed individuals.

Over the last years, publications have proposed an additional subtype of microscopic colitis, microscopic colitis incomplete, comprising incomplete collagenous colitis and incomplete lymphocytic colitis 33. Microscopic colitis incomplete embraces patients with clinical features of microscopic colitis from whom biopsies fall short of fulfilling the specific histological criteria of collagenous colitis and lymphocytic colitis. Fraser 34 suggested the term “microscopic colitis not otherwise specified” for this group of patients. The histological key features of microscopic colitis and microscopic colitis incomplete are shown in Table 2.

As patients with microscopic colitis incomplete seem to benefit from medical treatment with a clinical response equal to patients with microscopic colitis, it has been suggested to include microscopic colitis incomplete as a subgroup of microscopic colitis 35.

Table 2. Histological key features of microscopic colitis (collagenous colitis and lymphocytic colitis) and MCi (collagenous colitis incomplete and lymphocytic colitis incomplete)

| Clinical groups | Morphology subgroups | Increased mononuclear inflammation of lamina propria | Thickness of collagenous band | Number of intraepithelial lymphocytes |

|---|---|---|---|---|

| Microscopic colitis | Collagenous colitis | Moderately increased | Thickening (≥10 μm) | Normal/slightly increased |

| Lymphocytic colitis | Moderately increased | Normal/slightly increased (<10 μm) | >20 intraepithelial lymphocytes per 100 epithelial cells | |

| Microscopic colitis incomplete | Collagenous colitis incomplete and lymphocytic colitis incomplete | Slightly increased | >5 and <10 μm | >10 intraepithelial lymphocytes and <20 intraepithelial lymphocytes |

Footnote: IELs, intraepithelial lymphocytes.

[Source 16 ]Does microscopic colitis increase the risk of colon cancer?

No. Unlike the other inflammatory bowel diseases, such as Crohn’s disease and ulcerative colitis, microscopic colitis does not increase a person’s risk of getting colon cancer. Most people are successfully treated for microscopic colitis.

Is microscopic colitis an autoimmune disease?

Scientists aren’t sure what causes microscopic colitis, but there is a strong association of microscopic colitis with autoimmune disorders, such as celiac disease, polyarthritis, and thyroid disorders (see below). Up to twenty to 60% of patients with lymphocytic colitis and 17%-40% of patients with collagenous colitis have autoimmune disease 36. In fact, histological features of Microscopic colitis in the colon are present in 30% of patients with celiac disease. While no specific genetic mutations have been identified as direct cause of Microscopic colitis, some studies have found common genetic abnormalities. For instance, there is an increased prevalence of human leukocyte antigen (HLA) DR3 DQ2 allele in patients with Microscopic colitis, and metalloproteinase 9 gene variations have been associated with collagenous colitis 37.

Experts have found that some people with microscopic colitis also have other disorders related to the immune system. These disorders include:

- Celiac disease—a condition in which people cannot tolerate gluten because it damages the lining of the small intestine and prevents absorption of nutrients. Gluten is a protein found in wheat, rye, and barley.

- Thyroid diseases such as:

- Hashimoto’s disease—a form of chronic, or long lasting, inflammation of the thyroid.

- Graves’ disease—a disease that causes hyperthyroidism. Hyperthyroidism is a disorder that occurs when the thyroid gland makes more thyroid hormone than the body needs.

- Rheumatoid arthritis—a disease that causes pain, swelling, stiffness, and loss of function in the joints when the immune system attacks the membrane lining the joints.

- Psoriasis—a skin disease that causes thick, red skin with flaky, silver-white patches called scales.

- Type 1 diabetes — a lifelong (chronic) disease in which there is a high level of sugar (glucose) in the blood.

Who is more likely to have microscopic colitis?

Anyone can develop microscopic colitis. The disease is more common in:

- Older adults. The average age at which people are diagnosed with microscopic colitis is 60 to 65 years 38. However, microscopic colitis may occur in people of any age, including children.

- Women. Research suggests the disease is three to nine times more common in women than in men 38.

- People who have certain immune disorders.

- Smokers.

- People who take medicines that have been linked to an increased risk for microscopic colitis.

The colon

The colon is part of the gastrointestinal (GI) tract, a series of hollow organs joined in a long, twisting tube from the mouth to the anus—a 1-inch-long opening through which stool leaves the body. Organs that make up the GI tract are the:

- mouth

- esophagus

- stomach

- small intestine

- large intestine

- anus

The first part of the GI tract, called the upper GI tract, includes the mouth, esophagus, stomach, and small intestine. The last part of the GI tract, called the lower GI tract, consists of the large intestine and anus. The intestines are sometimes called the bowel.

The large intestine is about 5 feet long in adults and includes the colon and rectum. The large intestine changes waste from liquid to a solid matter called stool. Stool passes from the colon to the rectum. The rectum is 6 to 8 inches long in adults and is between the last part of the colon—called the sigmoid colon—and the anus. During a bowel movement, stool moves from the rectum to the anus and out of the body.

Figure 1. Small and large intestines

Figure 2. Large intestine (colon)

Microscopic colitis causes

The exact cause of microscopic colitis is unknown. Several factors may play a role in causing microscopic colitis. However, most scientists believe that microscopic colitis results from an abnormal immune-system response to bacteria that normally live in the colon. Scientists have proposed other causes, including 39, 40, 41, 42, 43, 44, 45, 46:

- Abnormal immune reactions. Abnormal reactions of the immune system may play a role in causing microscopic colitis. Abnormal immune reactions lead to inflammation in the large intestine (colon). People who have certain immune disorders—such as celiac disease, rheumatoid arthritis or type 1 diabetes—are more likely to develop microscopic colitis. Scientists are studying the links between microscopic colitis and these immune disorders.

- Medications. Taking certain medicines may increase the risk of developing microscopic colitis. These medicines include:

- nonsteroidal anti-inflammatory drugs (NSAIDs)

- proton pump inhibitors (PPIs)

- selective serotonin reuptake inhibitors (SSRIs), a type of antidepressant

- hormone replacement therapy and oral contraceptives

- beta blockers, medicines that slow your heart rate

- statins, medications to lower cholesterol

- Infections with Clostridioides difficile, norovirus, Escherichia species, Campylobacter concisus, and H. pylori.

- Genetic factors. Research suggests certain genes increase the chance a person will develop microscopic colitis.

- Bile acid malabsorption —in which the small intestine doesn’t absorb enough bile acid and extra bile acid passes into the large intestine (colon)

- Smoking. Studies suggest people who smoke cigarettes are more likely to develop microscopic colitis. Among people who develop microscopic colitis, those who smoke tend to develop the disease at a younger age.

- Alcohol consumption. Alcohol consumption may alter the integrity of the intestinal epithelial barrier including the gut micriobiota resulting in dysbiosis, and intestinal overgrowth of endotoxin-producing bacteria

- Other factors. Researchers are studying other factors that may play a role in causing or worsening microscopic colitis. These factors include:

- changes in the microbiome

- female hormones

- body mass index (BMI)

Autoimmune Diseases

Sometimes people with microscopic colitis also have autoimmune diseases—disorders in which the body’s immune system attacks the body’s own cells and organs.

Experts have found that some people with microscopic colitis also have other disorders related to the immune system. These disorders include:

- Celiac disease—a condition in which people cannot tolerate gluten because it damages the lining of the small intestine and prevents absorption of nutrients. Gluten is a protein found in wheat, rye, and barley.

- Thyroid diseases such as:

- Hashimoto’s disease—a form of chronic, or long lasting, inflammation of the thyroid.

- Graves’ disease—a disease that causes hyperthyroidism. Hyperthyroidism is a disorder that occurs when the thyroid gland makes more thyroid hormone than the body needs.

- Rheumatoid arthritis—a disease that causes pain, swelling, stiffness, and loss of function in the joints when the immune system attacks the membrane lining the joints.

- Psoriasis—a skin disease that causes thick, red skin with flaky, silver-white patches called scales.

- Type 1 diabetes — a lifelong (chronic) disease in which there is a high level of sugar (glucose) in the blood.

Medications

Researchers have not found that medications cause microscopic colitis. However, they have found links between microscopic colitis and certain medications, most commonly:

- Nonsteroidal anti-inflammatory drugs (NSAIDs) such as aspirin, ibuprofen (Advil, Motrin IB, others) and naproxen sodium (Aleve)

- Proton pump inhibitors (PPIs) including lansoprazole (Prevacid), esomeprazole (Nexium), pantoprazole (Protonix), rabeprazole (Aciphex), omeprazole (Prilosec) and dexlansoprazole (Dexilant)

- Acarbose (Prandase, Precose)

- Flutamide (Eulexin)

- Ranitidine (Tritec, Zantac)

- Selective serotonin reuptake inhibitors (SSRIs) such as sertraline (Zoloft)

- Ticlopidine (Ticlid)

Oher medications linked to microscopic colitis include:

- Carbamazepine (Carbatrol, Tegretol)

- Clozapine (Clozaril, Fazaclo)

- Dexlansoprazole (Kapidex, Dexilant)

- Entacapone (Comtan)

- Esomeprazole (Nexium)

- Lisinopril (Prinivil, Zestril)

- Omeprazole (Prilosec)

- Pantoprazole (Protonix)

- Paroxetine (Paxil, Pexeva)

- Rabeprazole (AcipHex)

- Simvastatin (Zocor)

- Topiramate

- Vinorelbine (Navelbine)

Infections

- Bacteria. Some people get microscopic colitis after an infection with certain harmful bacteria. Harmful bacteria may produce toxins that irritate the lining of the colon.

- Viruses. Some scientists believe that viral infections that cause inflammation in the GI tract may play a role in causing microscopic colitis.

Genetic Factors

Some scientists believe that genetic factors may play a role in microscopic colitis. Although researchers have not yet found a gene unique to microscopic colitis, scientists have linked dozens of genes to other types of inflammatory bowel disease, including:

- Crohn’s disease—a disorder that causes inflammation and irritation of any part of the GI tract

- Ulcerative colitis—a chronic disease that causes inflammation and ulcers in the inner lining of the large intestine

Bile Acid Malabsorption

Some scientists believe that bile acid malabsorption plays a role in microscopic colitis. Bile acid malabsorption is the intestines’ inability to completely reabsorb bile acids—acids made by the liver that work with bile to break down fats. Bile is a fluid made by the liver that carries toxins and waste products out of the body and helps the body digest fats. Bile acids that reach the colon can lead to diarrhea.

Risk factors for microscopic colitis

Risk factors for microscopic colitis include:

- Age and gender. Microscopic colitis is most common in people ages 50 to 70 and more common in women than men. Some researchers suggest an association with a decrease in hormones in women after menopause.

- Autoimmune disease. People with microscopic colitis sometimes also have an autoimmune disorder, such as celiac disease, thyroid disease, rheumatoid arthritis, type 1 diabetes or psoriasis.

- Genetic link. Research suggests that there may be a connection between microscopic colitis and a family history of irritable bowel syndrome.

- Smoking. Recent research studies have shown an association between tobacco smoking and microscopic colitis, especially in people ages 16 to 44.

Some research studies indicate that using certain medications may increase your risk of microscopic colitis. But not all studies agree. Medications that may be linked to the condition include:

- Aspirin, acetaminophen (Tylenol, others) and ibuprofen (Advil, Motrin IB, others)

- Proton pump inhibitors including lansoprazole (Prevacid), esomeprazole (Nexium), pantoprazole (Protonix), rabeprazole (Aciphex), omeprazole (Prilosec) and dexlansoprazole (Dexilant)

- Acarbose (Precose)

- Flutamide

- Ranitidine (Zantac)

- Selective serotonin reuptake inhibitors (SSRIs) such as sertraline (Zoloft)

- Carbamazepine (Carbatrol, Tegretol)

- Clozapine (Clozaril, Fazaclo)

- Entacapone (Comtan)

- Paroxetine (Paxil, Pexeva)

- Simvastatin (Zocor).

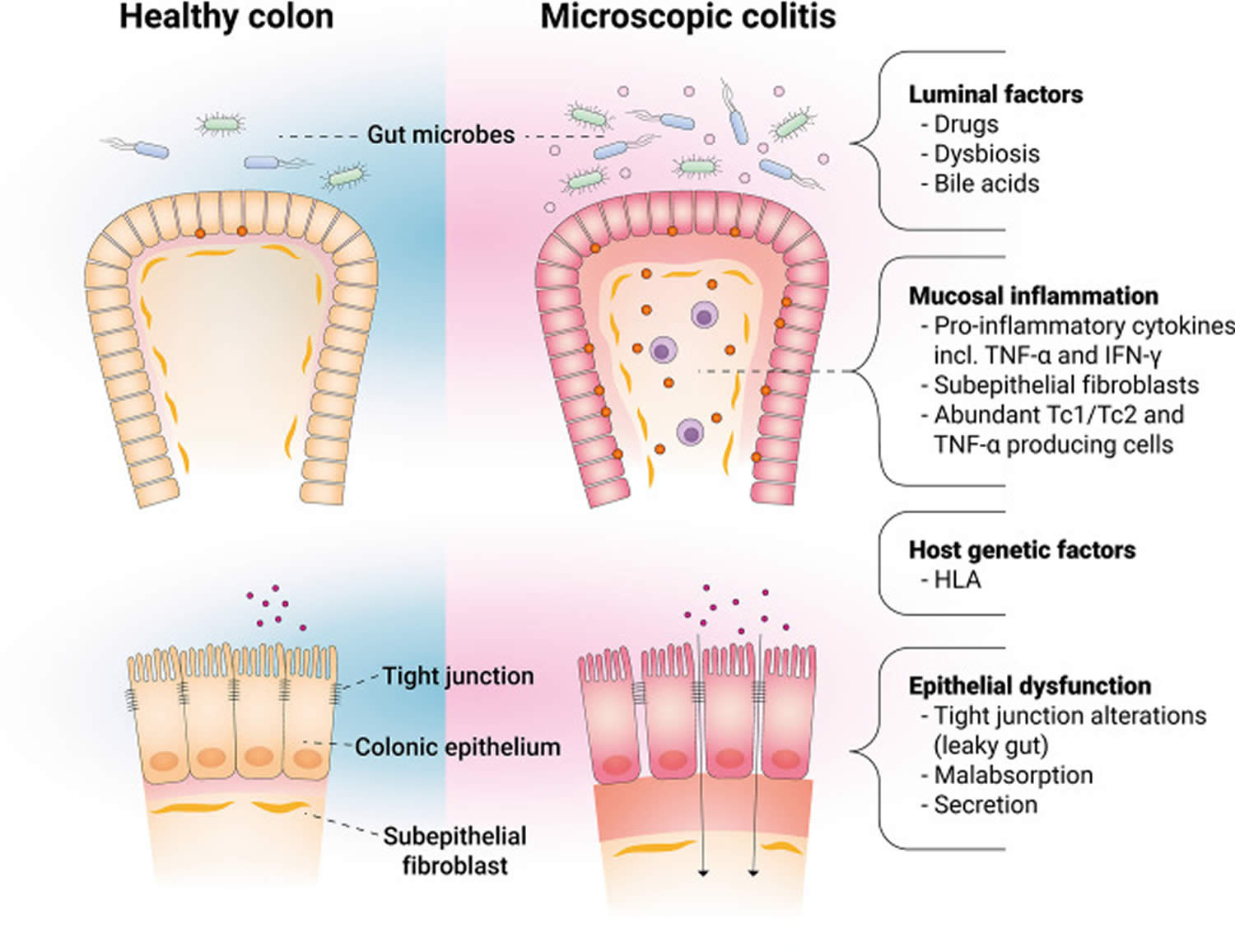

Microscopic colitis pathophysiology

The pathogenesis of microscopic colitis is still poorly understood, but it is likely a result of imbalanced immune response involving epithelial dysfunction 47, collagen metabolism, secretory diarrhea 48, and gut microbiota (gut micro-organisms) 49, 50, combined with the risk factors mentioned above in genetically predisposed individuals 51, 52, 53.

Figure 3. Main factors involved in the pathophysiology of microscopic colitis

[Source 5 ]Alteration of microbiota

The bacterial flora in the colon is an important luminal factor that directly or indirectly interacts with colonic epithelium, and its alteration might contribute to the pathogenesis of microscopic colitis 5. Although microscopic colitis is considered as a noninfectious colitis, recent advances in sequencing analysis have demonstrated an imbalance in the gut microbial community that is associated with disease, referred to as dysbiosis. A recent sequencing study showed microbiota from microscopic colitis to be significantly less diverse and compositionally distinct from healthy controls due to depletion of members of Clostridiales; enriched for Prevotella and more likely dominated by this genus 54. Two recent studies revealed a lowered intestinal bacterial diversity and a reduction in the abundance of several genera in microscopic colitis, including Akkermansia and Ruminococcus 55, 56. Akkermansia muciniphila adheres to the intestinal epithelium and strengthens enterocyte monolayer integrity in vitro, suggesting that Akkermansia muciniphila reduction may cause intestinal barrier dysfunction 57. More recently, a team of researchers 50, 58 found a higher long-term risk of developing microscopic colitis in patients whose stool carried Campylobacter concisus. Campylobacter concisus is a commensal of the human oral microbiota, which occasionally may be isolated from stool samples. Campylobacter concisus is associated with epithelial sodium channel dysfunction and claudin-8-dependent barrier dysfunction, suggesting their involvement in the pathogenesis of microscopic colitis 59. Notably, the use of proton pump inhibitor (PPI) and smoking influences bacterial flora 60, especially the use of proton pump inhibitor (PPI) may especially increase the abundance of oral microbes, such as Campylobacter concisus 61, suggesting that dysbiosis (an imbalance in the gut microbial community that is associated with disease) may be the mechanism by which these factors cause microscopic colitis. Meanwhile, diarrhea itself might also change the bacterial composition 62. Therefore, it remains unclear whether the dysbiosis is causal or secondary to microscopic colitis. Nevertheless, the altered intestinal microbiota composition is driven toward the composition of healthy controls once patients are in remission 63.

Microscopic colitis prevention

Researchers do not know how to prevent microscopic colitis. However, researchers do believe that people who follow the recommendations of their health care provider may be able to prevent relapses of microscopic colitis.

Microscopic colitis symptoms

The most common symptom of microscopic colitis is chronic, watery, nonbloody diarrhea. Episodes of diarrhea can last for weeks, months, or even years. However, many people with microscopic colitis may have long periods without diarrhea. Other signs and symptoms of microscopic colitis can include:

- Chronic watery nonbloody diarrhea (most common symptom)

- Diarrhea that occurs at night

- A strong urgency to have a bowel movement or a need to go to the bathroom quickly

- Pain, cramping, or bloating in the abdomen—the area between the chest and the hips—that is usually mild

- Weight loss

- Fecal incontinence—accidental passing of stool or fluid from the rectum—especially at night

- Nausea

- Dehydration—a condition that results from not taking in enough liquids to replace fluids lost through diarrhea

- Fatigue, or feeling tired

The symptoms of microscopic colitis can come and go frequently. Sometimes, the symptoms go away without treatment.

Microscopic colitis symptoms may start suddenly or begin gradually and become worse over time. Symptoms may vary in severity. For example, many people with microscopic colitis have four to nine bowel movements a day, but some people with microscopic colitis may have more than 10 bowel movements a day 64, 65.

You may experience remission—times when you have fewer symptoms or symptoms disappear. After a period of remission, you may have a relapse—a time when symptoms return or worsen.

Microscopic colitis complications

Compared with other types of inflammatory bowel disease (Crohn’s disease and ulcerative colitis), microscopic colitis is less likely to lead to complications. If microscopic colitis causes severe diarrhea, it may lead to weight loss and dehydration. In rare cases, microscopic colitis may cause serious complications, such as ulcers or perforation of the colon. Microscopic colitis does not increase your risk of colon cancer.

Microscopic colitis diagnosis

A pathologist—a doctor who specializes in examining tissues to diagnose diseases—diagnoses microscopic colitis based on the findings of multiple biopsies taken throughout the colon. Biopsy is a procedure that involves taking small pieces of tissue for examination with a microscope. The pathologist examines the colon tissue samples in a lab. Many patients can have both lymphocytic colitis and collagenous colitis in different parts of their colon.

To help diagnose microscopic colitis, a gastroenterologist—a doctor who specializes in digestive diseases—begins with:

- a medical and family history

- a physical exam

The gastroenterologist may perform a series of medical tests to rule out other bowel diseases—such as irritable bowel syndrome, celiac disease, Crohn’s disease, ulcerative colitis, and infectious colitis—that cause symptoms similar to those of microscopic colitis.

These medical tests include:

- lab tests

- imaging tests of the intestines

- endoscopy of the intestines

Medical and Family History

The gastroenterologist will ask the patient to provide a medical and family history, a review of the symptoms, a description of eating habits, and a list of prescription and over-the-counter medications in order to help diagnose microscopic colitis. The gastroenterologist will also ask the patient about current and past medical conditions.

Physical Exam

A physical exam may help diagnose microscopic colitis and rule out other diseases. During a physical exam, the gastroenterologist usually:

- examines the patient’s body

- taps on specific areas of the patient’s abdomen

Lab Tests

Lab tests may include:

- blood tests

- stool tests

Blood tests

A blood test involves drawing blood at a health care provider’s office or a commercial facility and sending the sample to a lab for analysis. A health care provider may use blood tests to help look for changes in red and white blood cell counts.

Red blood cells. When red blood cells are fewer or smaller than normal, a person may have anemia—a condition that prevents the body’s cells from getting enough oxygen.

White blood cells. When the white blood cell count is higher than normal, a person may have inflammation or infection somewhere in the body.

Stool tests

A stool test is the analysis of a sample of stool. A health care provider will give the patient a container for catching and storing the stool. The patient returns the sample to the health care provider or a commercial facility that will send the sample to a lab for analysis. Health care providers commonly order stool tests to rule out other causes of GI diseases, such as different types of infections—including bacteria or parasites—or bleeding, and help determine the cause of symptoms.

Imaging Tests of the Intestines

Imaging tests of the intestines may include the following:

- computerized tomography (CT) scan

- magnetic resonance imaging (MRI)

- upper GI series

Specially trained technicians perform these tests at an outpatient center or a hospital, and a radiologist—a doctor who specializes in medical imaging—interprets the images. A patient does not need anesthesia. Health care providers use imaging tests to show physical abnormalities and to diagnose certain bowel diseases, in some cases.

CT scan. CT scans use a combination of x-rays and computer technology to create images. For a CT scan, a health care provider may give the patient a solution to drink and an injection of a special dye, called contrast medium. CT scans require the patient to lie on a table that slides into a tunnel-shaped device where the technician takes the x-rays.

MRI. MRI is a test that takes pictures of the body’s internal organs and soft tissues without using x-rays. Although a patient does not need anesthesia for an MRI, some patients with a fear of confined spaces may receive light sedation, taken by mouth. An MRI may include a solution to drink and injection of contrast medium. With most MRI machines, the patient will lie on a table that slides into a tunnel-shaped device that may be open ended or closed at one end. Some machines allow the patient to lie in a more open space. During an MRI, the patient, although usually awake, must remain perfectly still while the technician takes the images, which usually takes only a few minutes. The technician will take a sequence of images to create a detailed picture of the intestines. During sequencing, the patient will hear loud mechanical knocking and humming noises.

Upper GI series. This test is an x-ray exam that provides a look at the shape of the upper GI tract. A patient should not eat or drink before the procedure, as directed by the health care provider. Patients should ask their health care provider about how to prepare for an upper GI series. During the procedure, the patient will stand or sit in front of an x-ray machine and drink barium, a chalky liquid. Barium coats the upper GI tract so the radiologist and gastroenterologist can see the organs’ shapes more clearly on x-rays. A patient may experience bloating and nausea for a short time after the test. For several days afterward, barium liquid in the GI tract causes white or light-colored stools. A health care provider will give the patient specific instructions about eating and drinking after the test.

Endoscopy of the Intestines

Endoscopy of the intestines may include:

- colonoscopy with biopsy

- flexible sigmoidoscopy with biopsy

- upper GI endoscopy with biopsy

A gastroenterologist performs these tests at a hospital or an outpatient center.

Colonoscopy with biopsy

Colonoscopy is a test that uses a long, flexible, narrow tube with a light and tiny camera on one end, called a colonoscope or scope, to look inside the rectum and entire colon. In most cases, light anesthesia and pain medication help patients relax for the test. The medical staff will monitor a patient’s vital signs and try to make him or her as comfortable as possible. A nurse or technician places an intravenous (IV) needle in a vein in the arm or hand to give anesthesia.

For the test, the patient will lie on a table while the gastroenterologist inserts a colonoscope into the anus and slowly guides it through the rectum and into the colon. The scope inflates the large intestine with air to give the gastroenterologist a better view. The camera sends a video image of the intestinal lining to a computer screen, allowing the gastroenterologist to carefully examine the tissues lining the colon and rectum. The gastroenterologist may move the patient several times and adjust the scope for better viewing. Once the scope has reached the opening to the small intestine, the gastroenterologist slowly withdraws it and examines the lining of the colon and rectum again. A colonoscopy can show irritated and swollen tissue, ulcers, and abnormal growths such as polyps—extra pieces of tissue that grow on the lining of the intestine. If the lining of the rectum and colon appears normal, the gastroenterologist may suspect microscopic colitis and will biopsy multiple areas of the colon.

A health care provider will provide written bowel prep instructions to follow at home before the test. The health care provider will also explain what the patient can expect after the test and give discharge instructions.

Figure 4. Colonoscopy

Flexible sigmoidoscopy with biopsy

Flexible sigmoidoscopy is a test that uses a flexible, narrow tube with a light and tiny camera on one end, called a sigmoidoscope or scope, to look inside the rectum and the sigmoid colon. A patient does not usually need anesthesia.

For the test, the patient will lie on a table while the gastroenterologist inserts the sigmoidoscope into the anus and slowly guides it through the rectum and into the sigmoid colon. The scope inflates the large intestine with air to give the gastroenterologist a better view. The camera sends a video image of the intestinal lining to a computer screen, allowing the gastroenterologist to carefully examine the tissues lining the sigmoid colon and rectum. The gastroenterologist may ask the patient to move several times and adjust the scope for better viewing. Once the scope reaches the end of the sigmoid colon, the gastroenterologist slowly withdraws it while carefully examining the lining of the sigmoid colon and rectum again.

The gastroenterologist will look for signs of bowel diseases and conditions such as irritated and swollen tissue, ulcers, and polyps. If the lining of the rectum and colon appears normal, the gastroenterologist may suspect microscopic colitis and will biopsy multiple areas of the colon.

A health care provider will provide written bowel prep instructions to follow at home before the test. The health care provider will also explain what the patient can expect after the test and give discharge instructions.

Figure 5. Sigmoidoscopy

Upper GI endoscopy with biopsy

Upper GI endoscopy is a test that uses a flexible, narrow tube with a light and tiny camera on one end, called an endoscope or a scope, to look inside the upper GI tract. The gastroenterologist carefully feeds the endoscope down the esophagus and into the stomach and first part of the small intestine, called the duodenum. A small camera mounted on the endoscope transmits a video image to a monitor, allowing close examination of the intestinal lining. A health care provider may give a patient a liquid anesthetic to gargle or may spray anesthetic on the back of the patient’s throat. A health care provider will place an IV needle in a vein in the arm or hand to administer sedation. Sedatives help patients stay relaxed and comfortable. This test can show blockages or other conditions in the upper small intestine. A gastroenterologist may biopsy the lining of the small intestine during an upper GI endoscopy.

Figure 6. Upper GI endoscopy

Microscopic colitis treatment

Microscopic colitis may get better on its own. But when symptoms persist or are severe, you may need treatment to relieve them. In routine clinical practice, there is no difference in the treatment of lymphocytic colitis and collagenous colitis, as demonstrated by the approach of current European and American guidelines 15, 14, 66. Doctors usually try a stepwise approach, starting with the simplest, most easily tolerated treatments.

The first step in nicroscopic colitis management is to consider elimination of exacerbating factors; that is, to encourage smoking cessation and withdraw any culprit medications, that is, drugs with a suspected chronological relationship between drug introduction and onset of diarrhea. Although discontinuation of the offending drug leads to disease improvement in the majority of cases, 67, there is no clear evidence yet of how it might predictably alter the disease course.

Your gastroenterologist will:

- review the medications your are taking

- make recommendations to change or stop certain medications that could be causing microscopic colitis or making your symptoms worse

- recommend that you quit smoking

Your gastroenterologist may prescribe medications to help control your symptoms. Medications are almost always effective in treating microscopic colitis. The gastroenterologist may also recommend changing what you eat and drink to help improve symptoms. In rare cases, your gastroenterologist may recommend surgery.

Figure 7. An algorithm of diagnostic and therapeutic recommendations for patients with microscopic colitis

Abbreviations: BMs = bowel movements; TNF = tumor necrosis factor

[Source 1 ]Microscopic colitis diet

Scientists have not yet discovered dietary changes that heal microscopic colitis. However, in some cases, doctors may recommend changing what you eat and drink to help relieve persistent diarrhea symptoms. Changing what you eat and drink can also help reduce symptoms if you have another digestive disorder—such as lactose intolerance or celiac disease—in addition to microscopic colitis.

To help reduce symptoms, your doctor may recommend the following dietary changes:

- Eat a low-fat, low-fiber diet. Foods that contain less fat and are low in fiber may help relieve diarrhea.

- Discontinue dairy products (if you have lactose intolerance), gluten (if you have celiac disease) or both. These foods may make your symptoms worse.

- Avoid caffeine and sugar (including artificial sugars).

- Drink plenty of liquids to prevent dehydration during episodes of diarrhea.

- Discontinue any medication that might be a cause of your symptoms. Your doctor may recommend a different medication to treat an underlying condition.

You should talk with your doctor or dietitian about what type of foods and drinks are right for you.

A few studies have investigated the potential benefit of probiotics in microscopic colitis without evidence of clinical efficacy to date after treatment with Lactobacillus acidophilus and Bifidobacterium animalis subsp lactis 68. In a study that randomized 26 patients to receive placebo or Boswellia serrata extract, patients with collagenous colitis showed some clinical response, but the lack of histologic response combined with no improved quality-of-life scores means that this approach cannot be currently recommended 69. Further clinical trials would be useful to determine whether probiotics have a place within the clinical paradigm.

Medications

If signs and symptoms persist, your gastroenterologist may prescribe one or more of the following:

- Antidiarrheal medications such as bismuth subsalicylate (Kaopectate, Pepto-Bismol), diphenoxylate/atropine (Lomotil), and loperamide (Imodium)

- Corticosteroids such as budesonide (Entocort) and prednisone

- Anti-inflammatory medications such as mesalamine and sulfasalazine (Azulfidine), to help control colon inflammation

- Cholestyramine resin (cholestyramine/aspartame or cholestyramine [Prevalite], or colestipol [Colestid])—a medication that blocks bile acids

- Antibiotics such as metronidazole (Flagyl) and erythromycin

- Immunomodulators such as mercaptopurine (Purinethol), azathioprine (Azasan, Imuran), and methotrexate (Rheumatrex, Trexall), to help reduce inflammation in the colon

- Anti-TNF therapies such as infliximab (Remicade) and adalimumab (Humira), which can reduce inflammation by neutralizing an immune system protein known as tumor necrosis factor (TNF).

Corticosteroids are medications that decrease inflammation and reduce the activity of the immune system. These medications can have many side effects. Scientists have shown that budesonide is safer, with fewer side effects, than prednisone. Most health care providers consider budesonide the best medication for treating microscopic colitis. Budesonide is recommended as first-line therapy according to both American Gastroenterological Association guidelines and the European Microscopic Colitis Group statements 15, 14, 66.

Patients with microscopic colitis generally achieve relief through treatment with medications, although relapses can occur. Some patients may need long-term treatment if they continue to have relapses.

Randomized, controlled trials and meta-analyses favor budesonide for induction of clinical remission 1. A Cochrane systematic review reported budesonide to induce and to maintain response in collagenous colitis over 6 months with a number needed to treat of 2 per outcome. A minority of patients achieve histologic remission. Similar response rates were seen in lymphocytic colitis to induce response and a number needed to treat of 3 70. Budesonide improves quality-of-life scores using the gastrointestinal quality-of-life index 71. American Gastroenterological Association guidelines recommend an 8-week course of budesonide as first-line therapy for induction of clinical remission based on a meta-analysis of 6 studies showing a net beneficial effect and 152% increase in the likelihood of remission over 6 to 8 months 72. Data supporting the use of oral prednisolone for induction of remission are modest, so its use is not recommended as first-line treatment, particularly considering the side-effect burden associated with corticosteroids. An analysis of 17 patients treated with prednisolone vs 63 with budesonide showed lower remission rates and increased relapse with prednisolone 73.

Clinical relapse after stopping budesonide is common and reported in 40% to 81% as soon as 2 weeks after withdrawal 74. Analysis of predictors of recurrence identified risk factors, including older patients (>60 years), longer duration of symptoms (>12 months), and high daily stool frequency (>5/day). Maintenance therapy with oral budesonide may be required to restore quality of life and maintain clinical remission in a proportion of patients 75. Maintenance therapy with 4.5 mg of budesonide daily was associated with maintenance of remission, sustained improvement in quality-of-life scores for collagenous colitis patients, and nonserious adverse effects in 7 of 44 patients 74. Little research has examined the success rates of budesonide for maintenance of remission in lymphocytic colitis. Although minimal side effects have been reported in microscopic colitis during budesonide therapy 76, the association between long-term budesonide use and reduced bone density scores in Crohn’s disease 77 underlines the importance of monitoring bone health in these patients. For maintenance, the lowest effective dose of budesonide should be used. Consideration should also be given to the specific budesonide formulation used. The preferred form of budesonide is absorbed in the ileum and right colon, rather than the alternative, which is associated with mainly left colon absorption and, hence, may be less effective in microscopic colitis 72.

In case patients with microscopic colitis fail to respond to budesonide to induce and maintain clinical remission, and in those who develop significant side effects, additional therapies, such as loperamide, bile acid sequestrants, bismuth subsalicylate, thiopurines, and biologicals, may be considered 5.

The American Gastroenterological Association recommends that treatment with mesalamine or bismuth subsalicylate should be considered over no treatment when budesonide is contraindicated or fails 72. Treatment with bismuth subsalicylate was associated with favorable clinical outcomes in a small open-label study of lymphocytic colitis and collagenous colitis resulting in clinical and histologic responses 78. Clinical efficacy studies of mesalamine have yielded mixed results, finding this therapy inferior to budesonide for induction of remissio 79. Although mesalamine is recommended as second-line therapy in microscopic colitis, the clinical data available do not strongly support this recommendation. In lymphocytic colitis, mesalamine in combination with cholestyramine did not significantly increase the likelihood of achieving clinical remission, although in collagenous colitis, dual therapy was associated with a greater chance of remission than mesalamine alone. The modest increased response was offset by adverse effects 80. Despite morphologically normal distal ileum, bile acid malabsorption has been identified in approximately 40% of microscopic colitis patients in 2 studies, with induction of clinical remission following cholestyramine in 19 of 22 patients with abnormal 75Se-homocholic acid taurine scans 81. In the absence of bile acid malabsorption, there is weak evidence for clinical response to cholestyramine. These recommendations (Figure 6 above) are limited by a lack of controlled clinical trials for these drugs, with the exception of bismuth and budesonide, and some mixed results and methodologies in the available data. Standard antidiarrheal agents, including loperamide, may have a role in controlling symptoms in patients with mild clinical disease. Symptomatic improvement may also be provided by the elimination of dietary secretagogues such as caffeine, lactose, and fats.

Refractory microscopic colitis

Some patients may have persistent symptoms despite medical therapy. In these individuals, coexistent conditions such as celiac disease should be first excluded. If contraindicated, or relapse occurs despite budesonide maintenance, immunomodulators (azathioprine and 6-mercaptopurine) are reasonably efficacious in microscopic colitis, although their use may be limited by intolerance in approximately one-third of patients in this setting 82. Methotrexate has been used with mixed results in retrospective and prospective analyses, although inadequate power may have influenced the outcome 82. Similarly, calcineurin inhibitors have been used in individual reports and were well tolerated, but only 1 patient achieved complete response. These drugs are not currently recommended in refractory microscopic colitis 82.

A case series points to the use of anti–TNF-α agents in refractory disease 83. Excellent early response rates have been reported, with a reduction of daily stool frequency of up to 90% and sustained remission in a proportion of patients 83. One analysis over almost 20 years included 10 patients treated with anti–TNF-α therapy for a median of 4 months, and reported that a proportion of patients achieved partial response to anti–TNF-α therapy. Long-term use in microscopic colitis may not be necessary if a precipitating agent such as a PPI has been identified and discontinued 82.

Colectomy and consequent diversion of the fecal stream have been used to treat a small cohort of patients with medically refractory microscopic colitis. A case of lymphocytic colitis 84 and a case of collagenous colitis 85 successfully treated with colectomy and subsequent fashioning of ileal J-pouch have been reported. Although histologic remission does not always coexist with clinical remission after medical therapy, diversion of the fecal stream resolves histologic changes, which recur after ileostomy reversal 86.

Surgery

When the symptoms of microscopic colitis are severe and medications aren’t effective, a gastroenterologist may recommend surgery to remove the colon. Surgery is a rare treatment for microscopic colitis. The gastroenterologist will exclude other causes of symptoms before considering surgery.

Home remedies

Changes to your diet may help relieve diarrhea that you experience with microscopic colitis. Try to:

- Drink plenty of fluids. Water is best, but fluids with added sodium and potassium (electrolytes) may help as well. Try drinking broth or watered-down fruit juice. Avoid beverages that are high in sugar or sorbitol or contain alcohol or caffeine, such as coffee, tea and colas, which may aggravate your symptoms.

- Choose soft, easy-to-digest foods. These include applesauce, bananas, melons and rice. Avoid high-fiber foods such as beans and nuts, and eat only well-cooked vegetables. If you feel as though your symptoms are improving, slowly add high-fiber foods back to your diet.

- Eat several small meals rather than a few large meals. Spacing meals throughout the day may ease diarrhea.

- Avoid irritating foods. Stay away from spicy, fatty or fried foods and any other foods that make your symptoms worse.

Microscopic colitis prognosis

Many patients with microscopic colitis will have a chronic, intermittent course of disease symptoms 87. Diarrhea can sometimes resolve without treatment or will often resolve with treatment within weeks. Relapses of symptoms are frequent. It is currently unclear if collagenous colitis or lymphocytic colitis is worse than the other. At present, there is no associated increased risk of colorectal cancer with microscopic colitis.

References- Boland K, Nguyen GC. Microscopic Colitis: A Review of Collagenous and Lymphocytic Colitis. Gastroenterology & Hepatology. 2017;13(11):671-677. https://www.ncbi.nlm.nih.gov/pmc/articles/PMC5717882/

- Escudero-Hernández C, van Beelen Granlund A, Bruland T, Sandvik AK, Koch S, Østvik AE, Münch A. Transcriptomic profiling of collagenous colitis identifies hallmarks of nondestructive inflammatory bowel disease. Cellular and Molecular Gastroenterology and Hepatology. 2021;12:665–687. doi: 10.1016/j.jcmgh.2021.04.011

- Definition & Facts of Microscopic Colitis. https://www.niddk.nih.gov/health-information/digestive-diseases/microscopic-colitis/definition-facts

- Marlicz W, Skonieczna-Żydecka K, Yung DE, Loniewski I, Koulaouzidis A. Endoscopic findings and colonic perforation in microscopic colitis: A systematic review. Digestive and Liver Disease. 2004;49:1073–1085. doi: 10.1016/j.dld.2017.07.015

- Nielsen OH, Fernandez-Banares F, Sato T, Pardi DS. Microscopic colitis: Etiopathology, diagnosis, and rational management. Elife. 2022 Aug 1;11:e79397. doi: 10.7554/eLife.79397

- Vespa E, D’Amico F, Sollai M, Allocca M, Furfaro F, Zilli A, Dal Buono A, Gabbiadini R, Danese S, Fiorino G. Histological scores in patients with inflammatory bowel diseases: The state of the art. Journal of Clinical Medicine. 2022;11:939–952. doi: 10.3390/jcm11040939

- https://www.mayoclinic.org/diseases-conditions/microscopic-colitis/symptoms-causes/syc-20351478

- Gentile NM, Khanna S, Loftus EV Jr, Smyrk TC, Tremaine WJ, Harmsen WS, Zinsmeister AR, Kammer PP, Pardi DS. The epidemiology of microscopic colitis in Olmsted County from 2002 to 2010: a population-based study. Clin Gastroenterol Hepatol. 2014 May;12(5):838-42. doi: 10.1016/j.cgh.2013.09.066

- Fumery M, Kohut M, Gower-Rousseau C, et al. on behalf on the Somme MC group; EPIMAD group. Incidence, clinical presentation, and associated factors of microscopic colitis in northern France: a population-based study. Dig Dis Sci. 2017;62(6):1571–1579 https://www.ncbi.nlm.nih.gov/pubmed/27659673

- Bonderup OK, Wigh T, Nielsen GL, Pedersen L, Fenger-Grøn M. The epidemiology of microscopic colitis: A 10-year pathology-based nationwide Danish cohort study. Scandinavian Journal of Gastroenterology. 2015;50:393–398. doi: 10.3109/00365521.2014.940378

- Windon AL, Almazan E, Oliva-Hemker M, Hutchings D, Assarzadegan N, Salimian K, Montgomery EA, Voltaggio L. Lymphocytic and collagenous colitis in children and adolescents: Comprehensive clinicopathologic analysis with long-term follow-up. Human Pathology. 2020;106:13–22. doi: 10.1016/j.humpath.2020.09.011

- Tong J, Zheng Q, Zheng Q, Zhang C, Lo R, Shen J, Ran Z. Incidence, prevalence, and temporal trends of microscopic colitis: a systematic review and meta-analysis. The American Journal of Gastroenterology. 2015;110:265–276. doi: 10.1038/ajg.2014.431

- Olesen M, Eriksson S, Bohr J, Järnerot G, Tysk C. Lymphocytic colitis: a retrospective clinical study of 199 Swedish patients. Gut. 2004;53(4):536–541 https://www.ncbi.nlm.nih.gov/pmc/articles/PMC1774011/

- Miehlke S, Guagnozzi D, Zabana Y, Tontini GE, Kanstrup Fiehn AM, Wildt S, Bohr J, Bonderup O, Bouma G, D’Amato M, Heiberg Engel PJ, Fernandez-Banares F, Macaigne G, Hjortswang H, Hultgren-Hörnquist E, Koulaouzidis A, Kupcinskas J, Landolfi S, Latella G, Lucendo A, Lyutakov I, Madisch A, Magro F, Marlicz W, Mihaly E, Munck LK, Ostvik AE, Patai ÁV, Penchev P, Skonieczna-Żydecka K, Verhaegh B, Münch A. European guidelines on microscopic colitis: United European Gastroenterology and European Microscopic Colitis Group statements and recommendations. United European Gastroenterol J. 2021 Feb 22;9(1):13–37. doi: 10.1177/2050640620951905

- Pardi DS, Tremaine WJ, Carrasco-Labra A. American Gastroenterological Association Institute technical review on the medical management of microscopic colitis. Gastroenterology. 2016;150:247–274. doi: 10.1053/j.gastro.2015.11.006

- Engel PJH, Fiehn A-MK, Munck LK, Kristensson M. The subtypes of microscopic colitis from a pathologist’s perspective: past, present and future. Annals of Translational Medicine. 2018;6(3):69. doi:10.21037/atm.2017.03.16. https://www.ncbi.nlm.nih.gov/pmc/articles/PMC5879503/

- Weimers P, Ankersen DV, Lophaven S, Bonderup OK, Münch A, Løkkegaard ECL, Burisch J, Munkholm P. Incidence and prevalence of microscopic colitis between 2001 and 2016: A Danish nationwide cohort study. Journal of Crohn’s & Colitis. 2020;14:1717–1723. doi: 10.1093/ecco-jcc/jjaa108

- Bohr J, Tysk C, Eriksson S, Abrahamsson H, Järnerot G. Collagenous colitis: a retrospective study of clinical presentation and treatment in 163 patients. Gut. 1996;39(6):846–851. https://www.ncbi.nlm.nih.gov/pmc/articles/PMC1383457/

- Fedor I, Zold E, Barta Z. Microscopic colitis: controversies in clinical symptoms and autoimmune comorbidities. Annals of Medicine. 2021;53:1279–1284. doi: 10.1080/07853890.2021.1962965

- Wildt S, Munck LK, Winther-Jensen M, Jess T, Nyboe Andersen N. Autoimmune diseases in microscopic colitis: A Danish nationwide case-control study. Alimentary Pharmacology & Therapeutics. 2021;54:1454–1462. doi: 10.1111/apt.16614

- Fernandez-Banares F, de v MR, Salas A, Beltrán B, Piqueras M, Iglesias E, Gisbert JP, Lobo B, Puig-Diví V. Epidemiological risk factors in microscopic colitis: a prospective case-control study. Inflammatory Bowel Diseases. 2013;19:411–417. doi: 10.1097/MIB.0b013e318281f3cc

- Macaigne G, Lahmek P, Locher C, et al. Microscopic colitis or functional bowel disease with diarrhea: a French prospective multicenter study. Am J Gastroenterol. 2014;109(9):1461–1470. https://www.ncbi.nlm.nih.gov/pubmed/25001258

- Stewart M, Andrews CN, Urbanski S, Beck PL, Storr M. The association of coeliac disease and microscopic colitis: a large population-based study. Aliment Pharmacol Ther. 2011;33(12):1340–1349. https://www.ncbi.nlm.nih.gov/pubmed/21517923

- Macaigne G, Lahmek P, Locher C, et al. Microscopic colitis or functional bowel disease with diarrhea: a French prospective multicenter study. Am J Gastroenterol. 2014;109(9):1461–1470 https://www.ncbi.nlm.nih.gov/pubmed/25001258

- Fernandez-Bañares F, Esteve M, Salas A, Forné TM, Espinos JC, Martín-Comin J, Viver JM. Bile acid malabsorption in microscopic colitis and in previously unexplained functional chronic diarrhea. Digestive Diseases and Sciences. 2001;46:2231–2238. doi: 10.1023/a:1011927302076

- Jaruvongvanich V, Poonsombudlert K, Ungprasert P. Smoking and risk of microscopic colitis: A systematic review and meta-analysis. Inflammatory Bowel Diseases. 2019;25:672–678. doi: 10.1093/ibd/izy296

- Roth B, Gustafsson RJ, Jeppsson B, Manjer J, Ohlsson B. Smoking- and alcohol habits in relation to the clinical picture of women with microscopic colitis compared to controls. BMC Womens Health. 2014;14(1):16. https://www.ncbi.nlm.nih.gov/pmc/articles/PMC3905929/

- Yen EF, Pokhrel B, Du H, et al. Current and past cigarette smoking significantly increase risk for microscopic colitis. Inflamm Bowel Dis. 2012;18(10):1835–1841 https://www.ncbi.nlm.nih.gov/pubmed/22147506

- Zylberberg HM, Kamboj AK, De Cuir N, Lane CM, Khanna S, Pardi DS, Lebwohl B. Medication use and microscopic colitis: a multicentre retrospective cohort study. Alimentary Pharmacology & Therapeutics. 2021;53:1209–1215. doi: 10.1111/apt.16363

- Morgan DM, Cao Y, Miller K, McGoldrick J, Bellavance D, Chin SM, Halvorsen S, Maxner B, Richter JM, Sassi S, Burke KE, Yarze JC, Ludvigsson JF, Staller K, Chung DC, Khalili H. Microscopic colitis is characterized by intestinal dysbiosis. Clinical Gastroenterology and Hepatology. 2020;18:984–986. doi: 10.1016/j.cgh.2019.06.035

- Verhaegh BPM, de Vries F, Masclee AAM, Keshavarzian A, de Boer A, Souverein PC, Pierik MJ, Jonkers DMAE. High risk of drug-induced microscopic colitis with concomitant use of NSAIDs and proton pump inhibitors. Alimentary Pharmacology & Therapeutics. 2016;43:1004–1013. doi: 10.1111/apt.13583

- Bonderup OK, Nielsen GL, Dall M, Pottegård A, Hallas J. Significant association between the use of different proton pump inhibitors and microscopic colitis: a nationwide Danish case-control study. Alimentary Pharmacology & Therapeutics. 2018;48:618–625. doi: 10.1111/apt.14916

- Munck LK. Incomplete microscopic colitis: a broader and clinically relevant perspective. In: Miehlke S, Münch A, eds. Microscopic colitis—creating awareness for an underestimated disease. Basel: Falk Workshop, 2012:27-31.

- Fraser AG, Warren BF, Chandrapala R, et al. Microscopic colitis: a clinical and pathological review. Scand J Gastroenterol 2002;37:1241-5. 10.1080/003655202761020489 https://www.ncbi.nlm.nih.gov/pubmed/12465719

- Bjørnbak C, Engel PJ, Nielsen PL, et al. Microscopic colitis: clinical findings, topography and persistence of histopathological subgroups. Aliment Pharmacol Ther 2011;34:1225-34. 10.1111/j.1365-2036.2011.04865.x https://www.ncbi.nlm.nih.gov/pubmed/21967618

- Histology of microscopic colitis-review with a practical approach for pathologists. Langner C, Aust D, Ensari A, Villanacci V, Becheanu G, Miehlke S, Geboes K, Münch A, Working Group of Digestive Diseases of the European Society of Pathology (ESP) and the European Microscopic Colitis Group (EMCG). Histopathology. 2015 Apr; 66(5):613-26. https://www.ncbi.nlm.nih.gov/pubmed/25381724/

- Allelic variation of the matrix metalloproteinase-9 gene is associated with collagenous colitis. Madisch A, Hellmig S, Schreiber S, Bethke B, Stolte M, Miehlke S. Inflamm Bowel Dis. 2011 Nov; 17(11):2295-8. https://www.ncbi.nlm.nih.gov/pubmed/21305678/

- Miehlke S, Verhaegh B, Tontini GE, Madisch A, Langner C, Münch A. Microscopic colitis: pathophysiology and clinical management. Lancet Gastroenterol Hepatol. 2019 Apr;4(4):305-314. doi: 10.1016/S2468-1253(19)30048-2

- Yamile Zabana, Gian Tontini, Elisabeth Hultgren-Hörnquist, Karolina Skonieczna-Żydecka, Giovanni Latella, Ann Elisabeth Østvik, Wojciech Marlicz, Mauro D’Amato, Angel Arias, Stephan Miehlke, Andreas Münch, Fernando Fernández-Bañares, Alfredo J Lucendo, on behalf of the European Microscopic Colitis Group [EMCG], Pathogenesis of Microscopic Colitis: A Systematic Review, Journal of Crohn’s and Colitis, Volume 16, Issue 1, January 2022, Pages 143–161, https://doi.org/10.1093/ecco-jcc/jjab123

- Khalili H, Axelrad JE, Roelstraete B, Olén O, D’Amato M, Ludvigsson JF. Gastrointestinal Infection and Risk of Microscopic Colitis: A Nationwide Case-Control Study in Sweden. Gastroenterology. 2021 Apr;160(5):1599-1607.e5. doi: 10.1053/j.gastro.2021.01.004

- Nielsen HL, Dalager-Pedersen M, Nielsen H. High risk of microscopic colitis after Campylobacter concisus infection: population-based cohort study. Gut. 2020 Nov;69(11):1952-1958. doi: 10.1136/gutjnl-2019-319771

- Sonnenberg A, Turner KO, Genta RM. Interaction of Ethnicity and H. pylori Infection in the Occurrence of Microscopic Colitis. Dig Dis Sci. 2017 Apr;62(4):1009-1015. doi: 10.1007/s10620-016-4441-6

- Petra Weimers, Dorit Vedel Ankersen, Søren N Lophaven, Ole K Bonderup, Andreas Münch, Elsebeth Lynge, Ellen Christine Leth Løkkegaard, Pia Munkholm, Johan Burisch, Microscopic Colitis in Denmark: Regional Variations in Risk Factors and Frequency of Endoscopic Procedures, Journal of Crohn’s and Colitis, Volume 16, Issue 1, January 2022, Pages 49–56, https://doi.org/10.1093/ecco-jcc/jjab119

- Verhaegh, B.P.M., de Vries, F., Masclee, A.A.M., Keshavarzian, A., de Boer, A., Souverein, P.C., Pierik, M.J. and Jonkers, D.M.A.E. (2016), High risk of drug-induced microscopic colitis with concomitant use of NSAIDs and proton pump inhibitors. Aliment Pharmacol Ther, 43: 1004-1013. https://doi.org/10.1111/apt.13583

- Niccum B, Casey K, Burke K, Lopes EW, Lochhead P, Ananthakrishnan A, Richter JM, Ludvigsson JF, Chan AT, Khalili H. Alcohol Consumption is Associated With An Increased Risk of Microscopic Colitis: Results From 2 Prospective US Cohort Studies. Inflamm Bowel Dis. 2022 Aug 1;28(8):1151-1159. doi: 10.1093/ibd/izab220

- Veeravich Jaruvongvanich, MD, Kittika Poonsombudlert, MD, Patompong Ungprasert, MD, MS, Smoking and Risk of Microscopic Colitis: A Systematic Review and Meta-analysis, Inflammatory Bowel Diseases, Volume 25, Issue 4, April 2019, Pages 672–678, https://doi.org/10.1093/ibd/izy296

- Barmeyer C, Erko I, Awad K, Fromm A, Bojarski C, Meissner S, Loddenkemper C, Kerick M, Siegmund B, Fromm M, Schweiger MR, Schulzke JD. Epithelial barrier dysfunction in lymphocytic colitis through cytokine-dependent internalization of claudin-5 and -8. Journal of Gastroenterology. 2017;52:1090–1100. doi: 10.1007/s00535-017-1309-2

- Escudero-Hernández C, Münch A, Østvik AE, Granlund A, Koch S. The water channel aquaporin 8 is a critical regulator of intestinal fluid homeostasis in collagenous colitis. Journal of Crohn’s & Colitis. 2020;14:962–973. doi: 10.1093/ecco-jcc/jjaa020

- Khalili H, Axelrad JE, Roelstraete B, Olén O, D’Amato M, Ludvigsson JF. Gastrointestinal infection and risk of microscopic colitis: a nationwide case-control study in Sweden. Gastroenterology. 2021;160:1599–1607. doi: 10.1053/j.gastro.2021.01.004

- Aagaard MEY, Kirk KF, Nielsen H, Nielsen HL. High genetic diversity in Campylobacter concisus isolates from patients with microscopic colitis. Gut Pathogens. 2021;13:3. doi: 10.1186/s13099-020-00397-y

- Ianiro G, Cammarota G, Valerio L, Annicchiarico BE, Milani A, Siciliano M, Gasbarrini A. Microscopic colitis. World Journal of Gastroenterology. 2012;18:6206–6215. doi: 10.3748/wjg.v18.i43.6206

- Zabana Y, Tontini G, Hultgren-Hörnquist E, Skonieczna-Żydecka K, Latella G, Østvik AE, Marlicz W, D’Amato M, Arias A, Mielhke S, Münch A, Fernández-Bañares F, Lucendo AJ. Pathogenesis of microscopic colitis: A systematic review. Journal of Crohn’s & Colitis. 2022;16:143–161. doi: 10.1093/ecco-jcc/jjab123

- Liu Y, Chen M. Insights into the underlying mechanisms and clinical management of microscopic colitis in relation to other gastrointestinal disorders. Gastroenterol Rep (Oxf). 2022 Apr 7;10:goac011. doi: 10.1093/gastro/goac011

- Hertz S, Durack J, Kirk KF, Nielsen HL, Lin DL, Fadrosh D, Lynch K, Piceno Y, Thorlacius-Ussing O, Nielsen H, Lynch SV. Microscopic colitis patients possess a perturbed and inflammatory gut microbiota. Digestive Diseases and Sciences. 2022;67:2433–2443. doi: 10.1007/s10620-021-07045-8

- Carstens A, Dicksved J, Nelson R, Lindqvist M, Andreasson A, Bohr J, Tysk C, Talley NJ, Agréus L, Engstrand L, Halfvarson J. The gut microbiota in collagenous colitis shares characteristics with inflammatory bowel disease-associated dysbiosis. Clinical and Translational Gastroenterology. 2019;10:e00065. doi: 10.14309/ctg.0000000000000065

- van Hemert S, Skonieczna-Żydecka K, Loniewski I, Szredzki P, Marlicz W. Microscopic colitis-microbiome, barrier function and associated diseases. Annals of Translational Medicine. 2018;6:39. doi: 10.21037/atm.2017.03.83

- Reunanen J, Kainulainen V, Huuskonen L, Ottman N, Belzer C, Huhtinen H, de Vos WM, Satokari R. Akkermansia muciniphila adheres to enterocytes and strengthens the integrity of the epithelial cell layer. Applied and Environmental Microbiology. 2015;81:3655–3662. doi: 10.1128/AEM.04050-14

- Nielsen HL, Dalager-Pedersen M, Nielsen H. High risk of microscopic colitis after Campylobacter concisus infection: population-based cohort study. Gut. 2020;69:1952–1958. doi: 10.1136/gutjnl-2019-319771

- Nattramilarasu PK, Bücker R, Lobo de Sá FD, Fromm A, Nagel O, Lee IFM, Butkevych E, Mousavi S, Genger C, Kløve S, Heimesaat MM, Bereswill S, Schweiger MR, Nielsen HL, Troeger H, Schulzke JD. Campylobacter concisus impairs sodium absorption in colonic epithelium via ENaC dysfunction and claudin-8 disruption. International Journal of Molecular Sciences. 2020;21:373. doi: 10.3390/ijms21020373

- Shanahan ER, Shah A, Koloski N, Walker MM, Talley NJ, Morrison M, Holtmann GJ. Influence of cigarette smoking on the human duodenal mucosa-associated microbiota. Microbiome. 2018;6:150. doi: 10.1186/s40168-018-0531-3

- Schlenker C, Surawicz CM. Emerging infections of the gastrointestinal tract. Best Practice & Research. Clinical Gastroenterology. 2009;23:89–99. doi: 10.1016/j.bpg.2008.11.014

- Li Y, Xia S, Jiang X, Feng C, Gong S, Ma J, Fang Z, Yin J, Yin Y. Gut microbiota and diarrhea: An updated review. Frontiers in Cellular and Infection Microbiology. 2021;11:625210. doi: 10.3389/fcimb.2021.625210

- Rindom Krogsgaard L, Kristian Munck L, Bytzer P, Wildt S. An altered composition of the microbiome in microscopic colitis is driven towards the composition in healthy controls by treatment with budesonide. Scandinavian Journal of Gastroenterology. 2019;54:446–452. doi: 10.1080/00365521.2019.1599064

- Yen EF, Pardi DS. Chapter 74: Microscopic colitis and other miscellaneous inflammatory and structural disorders of the colon. In: Podolsky DK, Camilleri M, Fitz G, et al, eds. Yamada’s Textbook of Gastroenterology. 6th ed. John Wiley & Sons, Ltd: 2016:1479–1494.

- Townsend T, Campbell F, O’Toole P, Probert C. Microscopic colitis: diagnosis and management. Frontline Gastroenterol. 2019 Oct;10(4):388-393. doi: 10.1136/flgastro-2018-101040

- Nguyen GC, Smalley WE, Vege SS, Carrasco-Labra A, Clinical Guidelines Committee American Gastroenterological Association Institute guideline on the medical management of microscopic colitis. Gastroenterology. 2016;150:242–246. doi: 10.1053/j.gastro.2015.11.008

- Hamdeh S, Micic D, Hanauer S. Drug-Induced colitis. Clinical Gastroenterology and Hepatology. 2021;19:1759–1779. doi: 10.1016/j.cgh.2020.04.069

- Pardi DS, Tremaine WJ, Carrasco-Labra A. American Gastroenterological Association Institute Technical Review on the medical management of microscopic colitis. Gastroenterology. 2016;150(1):247–274.e11. https://www.ncbi.nlm.nih.gov/pubmed/26584602

- Madisch A, Miehlke S, Eichele O, et al. Boswellia serrata extract for the treatment of collagenous colitis. A double-blind, randomized, placebo-controlled, multicenter trial. Int J Colorectal Dis. 2007;22(12):1445–1451. https://www.ncbi.nlm.nih.gov/pubmed/17764013

- Chande N, MacDonald JK, McDonald JW. Interventions for treating microscopic colitis: a Cochrane Inflammatory Bowel Disease and Functional Bowel Disorders Review Group systematic review of randomized trials. Am J Gastroenterol. 2009;104(1):235–241 https://www.ncbi.nlm.nih.gov/pubmed/19098875

- Madisch A, Heymer P, Voss C, et al. Oral budesonide therapy improves quality of life in patients with collagenous colitis. Int J Colorectal Dis. 2005;20(4):312–316. https://www.ncbi.nlm.nih.gov/pubmed/15549326

- Nguyen GC, Smalley WE, Vege SS, Carrasco-Labra A Clinical Guidelines Committee. American Gastroenterological Association Institute Guideline on the medical management of microscopic colitis. Gastroenterology. 2016;150(1):242–246. quiz e17-e18. https://www.ncbi.nlm.nih.gov/pubmed/26584605

- Gentile NM, Abdalla AA, Khanna S, et al. Outcomes of patients with microscopic colitis treated with corticosteroids: a population-based study. Am J Gastroenterol. 2013;108(2):256–259 https://www.ncbi.nlm.nih.gov/pmc/articles/PMC3575108/

- Münch A, Bohr J, Miehlke S, et al. Low-dose budesonide for maintenance of clinical remission in collagenous colitis: a randomised, placebo-controlled, 12-month trial. Gut. 2016;65(1):47–56. https://www.ncbi.nlm.nih.gov/pmc/articles/PMC4717436/

- Miehlke S, Hansen JB, Madisch A, et al. Risk factors for symptom relapse in collagenous colitis after withdrawal of short-term budesonide therapy. Inflamm Bowel Dis. 2013;19(13):2763–2767 https://www.ncbi.nlm.nih.gov/pubmed/24216688

- Baert F, Schmit A, D’Haens G, et al. Belgian IBD Research Group; Codali Brussels. Budesonide in collagenous colitis: a double-blind placebo-controlled trial with histologic follow-up. Gastroenterology. 2002;122(1):20–25 https://www.ncbi.nlm.nih.gov/pubmed/11781276

- Cino M, Greenberg GR. Bone mineral density in Crohn’s disease: a longitudinal study of budesonide, prednisone, and nonsteroid therapy. Am J Gastroenterol. 2002;97(4):915–921. https://www.ncbi.nlm.nih.gov/pubmed/12003427

- Fine KD, Lee EL. Efficacy of open-label bismuth subsalicylate for the treatment of microscopic colitis. Gastroenterology. 1998;114(1):29–36. https://www.ncbi.nlm.nih.gov/pubmed/9428215

- Miehlke S, Madisch A, Kupcinskas L, et al. Budesonide is more effective than mesalamine or placebo in short-term treatment of collagenous colitis. Gastroenterology. 2014;146(5):1222–1230.e1-2. https://www.ncbi.nlm.nih.gov/pubmed/24440672

- Calabrese C, Fabbri A, Areni A, Zahlane D, Scialpi C, Di Febo G. Mesalazine with or without cholestyramine in the treatment of microscopic colitis: randomized controlled trial. J Gastroenterol Hepatol. 2007;22(6):809–814. https://www.ncbi.nlm.nih.gov/pubmed/17565633

- Fernandez-Bañares F, Esteve M, Salas A, et al. Bile acid malabsorption in microscopic colitis and in previously unexplained functional chronic diarrhea. Dig Dis Sci. 2001;46(10):2231–2238 https://www.ncbi.nlm.nih.gov/pubmed/11680602

- Cotter TG, Kamboj AK, Hicks SB, Tremaine WJ, Loftus EV, Pardi DS. Immune modulator therapy for microscopic colitis in a case series of 73 patients. Aliment Pharmacol Ther. 2017;46(2):169–174. https://www.ncbi.nlm.nih.gov/pubmed/28488312

- Esteve M, Mahadevan U, Sainz E, Rodriguez E, Salas A, Fernández-Bañares F. Efficacy of anti-TNF therapies in refractory severe microscopic colitis. J Crohns Colitis. 2011;5(6):612–618 https://www.ncbi.nlm.nih.gov/pubmed/22115383

- Varghese L, Galandiuk S, Tremaine WJ, Burgart LJ. Lymphocytic colitis treated with proctocolectomy and ileal J-pouch-anal anastomosis: report of a case. Dis Colon Rectum. 2002;45(1):123–126. https://www.ncbi.nlm.nih.gov/pubmed/11786777

- Williams RA, Gelfand DV. Total proctocolectomy and ileal pouch anal anastomosis to successfully treat a patient with collagenous colitis. Am J Gastroenterol. 2000;95(8):2147–2147. https://www.ncbi.nlm.nih.gov/pubmed/10950095

- Järnerot G, Tysk C, Bohr J, Eriksson S. Collagenous colitis and fecal stream diversion. Gastroenterology. 1995;109(2):449–455. https://www.ncbi.nlm.nih.gov/pubmed/7615194

- Hempel KA, Sharma AV. Collagenous And Lymphocytic Colitis. [Updated 2022 Sep 12]. In: StatPearls [Internet]. Treasure Island (FL): StatPearls Publishing; 2022 Jan-. Available from: https://www.ncbi.nlm.nih.gov/books/NBK541100