Molluscum contagiosum

Molluscum contagiosum is an infection caused by a Poxvirus (molluscum contagiosum virus) 1. Molluscum contagiosum is transmitted mainly by direct contact with infected skin 2. The result of the infection is usually a benign, mild skin disease characterized by umbilicated pink or skin-colored papules (growths) that may appear anywhere on the body 3. Within 6-12 months, Molluscum contagiosum typically resolves without scarring but may take as long as 4 years 4.

Children aged 2–5 years are most commonly affected with molluscum contagiosum, although it can occur in adolescents and adults 5. Molluscum contagiosum is rare in children aged younger than one year 4. In adolescents and adults, molluscum contagiosum could occur either as a sexually transmitted disease (STD) or in relation to contact sports 6. Molluscum contagiosum in adults is more common in immunosuppressed patients: in the 1980s, the number of reported cases of molluscum contagiosum increased, apparently associated with the onset of the acquired immune deficiency virus (HIV) epidemic 7. It is estimated that in human immunodeficiency virus (HIV) patients the prevalence is close to 20% 8. Besides HIV, molluscum contagiosum may be associated with medically induced immunosuppression or primary immunodeficiencies (eg, DOCK8 immunodeficiency syndrome) 9.

Molluscum contagiosum is more prevalent in warm climates than cool ones, and in overcrowded environments 10. In the United States, it is estimated that the prevalence of molluscum contagiosum in children is less than 5% 11.

Children with atopic eczema (atopic dermatitis) may be more severely affected by molluscum contagiosum due to the skin barrier breaks and immune cell dysfunction in atopic skin. In addition, these patients may be more likely to autoinoculate (excoriation of primary lesions and spread to areas of normal skin) new areas of skin because of the underlying itch (pruritus) from their atopy. However, studies on atopic dermatitis are controversial. Some studies have found an increased risk of molluscum contagiosum in patients with atopic dermatitis 12, 13, with prevalence rates of atopic dermatitis in patients with molluscum contagiosum of up to 62% 14, 15. It has even been hypothesized that an increased risk of molluscum contagiosum virus infection in patients with atopic dermatitis and filaggrin mutation 16. Other studies have shown no significant differences 17.

The lesions, known as Mollusca, are small, raised, and usually white, pink, or flesh-colored with a dimple or pit in the center. They often have a pearly appearance. They’re usually smooth and firm. In most people, the lesions range from about the size of a pinhead to as large as a pencil eraser (2 to 10 millimeters in diameter). They may become itchy, sore, red, and/or swollen.

Whenever you can see the bumps on the skin, molluscum contagiosum is contagious.

Most people get about 10 to 20 bumps on their skin. If a person has a weakened immune system, many bumps often appear.

Mollusca may occur anywhere on the body including the face, neck, arms, legs, abdomen, and genital area, alone or in groups. The lesions are rarely found on the palms of the hands or the soles of the feet.

Molluscum contagiosum can be very extensive and troublesome in patients with human immunodeficiency virus (HIV) infection or that have other reasons for poor immune function.

Patients with HIV/AIDS and other immunocompromising conditions (e.g., solid organ transplant recipients) can develop “giant” lesions (≥15 mm in diameter), larger numbers of lesions (100 or more molluscum contagiosum bumps) and lesions that are more resistant to standard therapy 18, 19, 20. The following diseases should be considered in the differential diagnosis of molluscum contagiosum: cryptococcosis, basal cell carcinoma, keratoacanthoma, histoplasmosis, coccidioidomycosis, and verruca vulgaris. For genital lesions, condyloma acuminata and vaginal syringomas should be considered.

Molluscum contagiosum lesions have recently come to be classified in one of three ways:

- The commonly seen skin lesions found largely on the faces, trunks, and limbs of children;

- The sexually transmitted lesions found on the abdomen, inner thighs, and genitals of sexually active adults; and

- The diffuse and recalcitrant eruptions of patients with AIDS or other immunosuppressive disorders.

Treatment of mild molluscum contagiosum infections is often not required because lesions will eventually resolve on their own. However, you can decrease the chance of spreading the infection to other parts of your body or to other people with the following guidelines:

- Do not scratch or shave the affected areas.

- Avoid sharing clothing, towels, and bedding with others.

- If the affected area is small, keep it covered.

The duration of molluscum contagiosum lesions is variable, but in most cases, they are self-limiting in a period of 6 to 9 months; however, some cases may persist for more than 3 or 4 years 21. It has been described a phenomenon called “beginning of the end” (BOTE) sign which refers to clinical erythema and swelling of an molluscum contagiosum skin lesion when the regression phase begins (Figure 3). This phenomenon is likely due to an immune response towards the molluscum contagiosum infection rather than a bacterial superinfection 2, 15, 22.

Figure 1. Molluscum contagiosum in children

Footnote: Each molluscum contagiosum starts out as a very small spot, about the size of a pinhead, and grows over several weeks into a larger bump that might become as large as a pea or pencil eraser. A tiny dimple (indentation) often develops on the top of each molluscum contagiosum.

Figure 2. Molluscum contagiosum papules

Footnote: Firm, rounded, skin-colored papules with a shiny and umbilicated surface.

Figure 3. Molluscum contagiosum regression

Footnote: Molluscum contagiosum regression with the “beginning of the end” (BOTE) sign which refers to clinical erythema and swelling of an molluscum contagiosum skin lesion

[Source 4 ]Molluscum contagiosum causes

Molluscum contagiosum is caused by molluscum contagiosum virus (MCV), a double-strand DNA virus which belongs to the Poxviridae family; humans are molluscum contagiosum virus only host 4. Molluscum contagiosum virus has 4 different genotypes: molluscum contagiosum virus 1 (MCV 1), molluscum contagiosum virus 2 (MCV 2), molluscum contagiosum virus 3 (MCV 3) and molluscum contagiosum virus 4 (MCV 4). Molluscum contagiosum virus 1 (MCV 1) is the most common genotype (75–96%), followed by molluscum contagiosum virus 2 (MCV 2), while molluscum contagiosum virus 3 (MCV 3) and molluscum contagiosum virus 4 (MCV 4) are extremely infrequent 2, 23, 24. A Slovenian study 23 showed that in children molluscum contagiosum virus 1 (MCV 1) infection is more frequent than in adults, and in adult women, molluscum contagiosum virus 2 (MCV 2) infection is more frequent than molluscum contagiosum virus 1 (MCV 1).

Molluscum contagiosum virus infects the epidermis and replicates in the cytoplasm of cells with a variable incubation period between two and six weeks 14. Different studies have been developed to sequence the genome of molluscum contagiosum virus (MCV) and determine possible genes involved in the evasion of the host immune response, a hypothesis that arose based on the absence of inflammation observed in histopathological samples of infected skin 25, 26. To date, four viral genes have been identified that code proteins that would alter the activation of the nuclear factor kB (NF-kB): MC159, MC160, MC132, and MC005 26, 27, 28, 29. Nuclear factor kB (NF-kB) is a nuclear protein complex present in dendritic cells that regulate the transcription of DNA and facilitate the synthesis of pro-inflammatory cytokines (TNF, IL-1, IL-6, among others) and activation of innate and acquired immune response 30. Brady et al 26 have seen that MC132 and MC005 proteins would alter the activation of NF-kB by inhibiting pattern recognition receptors (PRRs). Added to this, MC132 would bind and stimulate the degradation of the p65 subunit of NF-kB and MC005 would inhibit the activation of the IKK complex (IkB kinase) binding to active NEMO subunit (essential modulator of NF-kB).

Molluscum contagiosum virus is transmitted by direct contact with infected skin, which can be sexual, non-sexual, or by autoinoculation 4. Additionally, it can be transmitted by contaminated fomites like bath sponges or towels 2. It has been associated with the use of the swimming pool 14.

There are several ways the molluscum contagiosum virus can spread 31:

- Direct skin-to-skin contact

- Indirect contact via shared towels or other items

- Auto-inoculation into another site by scratching or shaving

- Sexual transmission in adults.

Transmission of molluscum contagiosum appears to be more likely in wet conditions, such as when children bathe or swim together. The incubation period is usually about 2 weeks but can be as long as 6 months.

How do people get molluscum contagiosum?

The virus that causes molluscum spreads from direct person-to-person physical contact and through contaminated fomites. Fomites are inanimate objects that can become contaminated with virus; in the instance of molluscum contagiosum this can include linens such as clothing and towels, bathing sponges, pool equipment, and toys. Although the virus might be spread by sharing swimming pools, baths, saunas, or other wet and warm environments, this has not been proven. Researchers who have investigated this idea think it is more likely the virus is spread by sharing towels and other items around a pool or sauna than through water.

Someone with molluscum contagiosum can spread it to other parts of their body by touching or scratching a lesion and then touching their body somewhere else. This is called autoinoculation. Shaving and electrolysis can also spread mollusca to other parts of the body.

Molluscum contagiosum can spread from one person to another by sexual contact 1. Many, but not all, cases of molluscum in adults are caused by sexual contact 1.

Conflicting reports make it unclear whether the disease may be spread by simple contact with seemingly intact lesions or if the breaking of a lesion and the subsequent transferring of core material is necessary to spread the virus.

Molluscum contagiosum lesions can also be congenital when transmitted vertically from mother to baby by contact with molluscum contagiosum virus in the birth canal 32, 33. In this case, molluscum contagiosum lesions are typically located on the scalp and have a circular arrangement 33. Other sites of atypical location, in addition to the oral mucosa 2, include the palms and soles, the areola/nipple 34, 35, the conjunctiva 36, lips 37, eyelids 38, among others 39. Clinical presentation of periocular lesions has been described as erythematous, nodular umbilicated, big/giant, conglomerated, inflamed, or pedunculated 40. The periocular presentation has also been associated with conjunctivitis 41.

The molluscum contagiosum virus remains in the top layer of skin (epidermis) and does not circulate throughout the body; therefore, it cannot spread through coughing or sneezing 1.

Since the virus lives only in the top layer of skin, once the lesions are gone the virus is gone and you cannot spread it to others 1. Molluscum contagiosum is not like herpes viruses, which can remain dormant (“sleeping”) in your body for long periods and then reappear.

Who is at risk for molluscum contagiosum infection?

Molluscum contagiosum is common enough that you should not be surprised if you see someone with it or if someone in your family becomes infected. Although not limited to children, it is most common in children 1 to 10 years of age.

People at increased risk for getting the disease include:

- People with weakened immune systems (i.e., HIV-infected persons or persons being treated for cancer) are at higher risk for getting molluscum contagiosum. Their growths may look different, be larger, and be more difficult to treat.

- Atopic dermatitis may also be a risk factor for getting molluscum contagiosum due to frequent breaks in the skin. People with this condition also may be more likely to spread molluscum contagiousm to other parts of their body for the same reason.

- People who live in warm, humid climates where living conditions are crowded.

In addition, there is evidence that molluscum contagiosum infections have been on the rise in the United States since 1966, but these infections are not routinely monitored because they are seldom serious and routinely disappear without treatment.

How can you prevent molluscum contagiosum from spreading?

The best way to avoid getting molluscum contagiosum is by following good hygiene habits. Remember that the virus lives only in the skin and once the lesions are gone, the virus is gone and you cannot spread the virus to others.

Wash your hands

There are ways to prevent the spread of molluscum contagiosum. The best way is to follow good hygiene (cleanliness) habits. Keeping your hands clean is the best way to avoid molluscum infection, as well as many other infections. Hand washing removes germs that may have been picked up from other people or from surfaces that have germs on them.

Don’t scratch or pick at molluscum contagiosum lesions

It is important not to touch, pick, or scratch skin that has lesions, that includes not only your own skin but anyone else’s. Picking and scratching can spread the virus to other parts of the body and makes it easier to spread the disease to other people too.

Keep molluscum contagiosum lesions covered

It is important to keep the area with molluscum lesions clean and covered with clothing or a bandage so that others do not touch the lesions and become infected. Do remember to keep the affected skin clean and dry.

Any time there is no risk of others coming into contact with your skin, such as at night when you sleep, uncover the lesions to help keep your skin healthy.

Be careful during sports activities

Do not share towels, clothing, or other personal items.

People with molluscum contagiosum should not take part in contact sports like wrestling, basketball, and football unless all lesions can be covered by clothing or bandages.

Activities that use shared gear like helmets, baseball gloves and balls should also be avoided unless all lesions can be covered.

Swimming should also be avoided unless all lesions can be covered by watertight bandages. Personal items such as towels, goggles, and swim suits should not be shared. Other items and equipment such as kick boards and water toys should be used only when all lesions are covered by clothing or watertight bandages.

Swimming pools

Parents and others often ask if molluscum virus can spread in swimming pools. There is also concern that it can spread by sharing swimming equipment, pool toys, or towels.

Some investigations report that spread of molluscum contagiosum is increased in swimming pools. However, it has not been proved how or under what circumstances swimming pools might increase spread of the virus. Activities related to swimming might be the cause. For example, the virus might spread from one person to another if they share a towel or toys. More research is needed to understand if and for how long the molluscum virus can live in swimming pool water and if such water can infect swimmers.

Open sores and breaks in the skin can become infected by many different germs. Therefore, people with open sores or breaks from any cause should not go into swimming pools.

If a person with molluscum contagiosum is going swimming, they should:

- Cover all visible lesions with watertight bandages

- Dispose of all used bandages at home

- Not share towels, kick boards, other equipment, or toys.

Day care centers and schools

There is no reason to keep a child with molluscum infection home from day care or school.

If you notice bumps on a child’s skin, it is reasonable to inform the child’s parents and to request a doctor’s note. Only a healthcare professional can diagnose molluscum contagiosum because there are many other causes of growths on the skin, both infectious and non-infectious.

Lesions not covered by clothing should be covered with a watertight bandage. Change the bandage daily or when obviously soiled.

If a child with lesions in the underwear/diaper area needs assistance going to the bathroom or needs diaper changes, then lesions in this area should be bandaged too if possible.

Covering the lesions will protect other children and adults from getting molluscum contagiosum and will also keep the child from touching and scratching the lesions, which could spread the infection to other parts of his/her body or cause secondary (bacterial) infections.

Children should be reminded to wash their hands frequently.

If day care or school employees with regular physical contact with others are normally required to have skin examinations during pre-employment physicals, then infection molluscum contagiosum should be noted.

Work

Although there has been only one reported case of healthcare provider-to-patient transmission of molluscum contagiosum, if an employee who comes in physical contact with clients regularly, such as an aesthetician or health care provider, is diagnosed with molluscum contagiosum by a health care professional, it would be reasonable to require that he/she cover visible lesions with a watertight dressing while at work. Otherwise, no special precautions are needed.

Other precautions can prevent or reduce spread to uninfected people:

- Frequent and correct hand hygiene practices.

- Requiring notation of molluscum contagiosum on examinations requested for—

- Employment

- Recommended only for employees with regular physical contact with clients (e.g., aestheticians, health care professionals, day care employees) who are normally required to have skin examinations during pre-employment physicals.

- Camp

- Sports physicals

- Employment

- Recommending that all visible lesions be covered by a watertight dressing, if molluscum contagiosum is diagnosed by a healthcare professional during a physical examination.

- Routinely disinfecting shared equipment (e.g., kick boards, wrestling mats). The molluscum contagiosum virus is not particularly difficult to kill and usual sanitation procedures should be sufficient.

Other ways to avoid sharing your molluscum contagiosum infection

Do not shave or have electrolysis on areas with lesions.

Don’t share personal items such as unwashed clothes, hair brushes, wrist watches, and bar soap with others.

If you have lesions on or near the penis, vulva, vagina, or anus, avoid sexual activities until you see a health care provider.

Molluscum contagiosum signs and symptoms

Molluscum contagiosum presents as clusters of small round dome-shaped papules (bumps). The firm rounded papules range in size from 2 to 10 mm and may be white, skin-colored, pink, pearly or brown and occur in clusters and sometimes in a straight line. They often have a waxy, shiny look with a small central pit (this appearance is sometimes described as umbilicated). Each papule contains white cheesy material. The molluscum contagiosum papules (bumps) may be single, multiple or clustered, and occasionally they may have an erythematous halo or be pediculated. Pruritus (itch) may be present.

There may be few or hundreds of papules on one individual. They mostly arise in warm moist places, such as the armpit, behind the knees, groin or genital areas. They can arise on the lips or rarely inside the mouth. They do not occur on palms or soles.

The bumps are usually painless and may occasionally itch. When molluscum contagiosum is autoinoculated by scratching, the papules often form a row. Individual bumps may get bigger over the course of 6–12 weeks. Usually the bumps do not grow larger than 10 mm, but in patients with weak immune systems, they can be larger than a nickel.

Molluscum contagiosum frequently induces dermatitis around them and affected skin becomes pink, dry and itchy. As the papules resolve, they may become inflamed, crusted or scabby for a week or two.

Molluscum contagiosum infections may be:

- Mild – under 10 lesions

- Moderate – about 10–50 lesions

- Severe – over 50 lesions

Common areas for molluscum contagiosum lesions are the chest, abdomen, back, armpits, groin, or backs of the knees. Occasionally, they can be seen on the face and genital region. Because the incubation period for molluscum contagiosum is 2 weeks to 6 months, lesions may not immediately be seen after contracting the virus. Molluscum contagiosum infection is self-limited, and lesions will go away on their own in 6–9 months, although they rarely can persist for a few years. As the bumps begin to resolve, they may initially appear more inflamed, with pus and crusting of the lesions, before they eventually fade. They usually do not leave a scar.

In children, the main affected areas are sites of exposed skin, such as the trunk, extremities, intertriginous regions, genitals, and face, except the palms and soles 42. The involvement of the oral mucosa is rare 43. In adults, lesions are most frequently located in the lower abdomen, thighs, genitals, and perianal area, most of the cases transmitted by sexual contact 4. In children, genital lesions are mainly due to autoinoculation and are not pathognomonic of sexual abuse 44.

Molluscum contagiosum complications

Complications of Molluscum contagiosum can include:

- Secondary bacterial infection from scratching (impetigo)

- Conjunctivitis when the eyelid is infected

- Disseminated secondary eczema; this represents an immunological reaction or ‘id’ to the virus

- Numerous and widespread molluscum contagiosum that are larger than usual may occur in immune-deficient patients (such as uncontrolled HIV infection or in patients on immune

- suppressing drugs), and often affect the face

- Spontaneous, pitted scarring

- Scarring due to surgical treatment

Molluscum contagiosum diagnosis

Your doctor will most likely be able to diagnose molluscum contagiosum by its appearance. Molluscum is usually recognized by its characteristic clinical appearance or on dermatoscopy (Figure 4) 2. White molluscum bodies can often be expressed from the center of the papules.

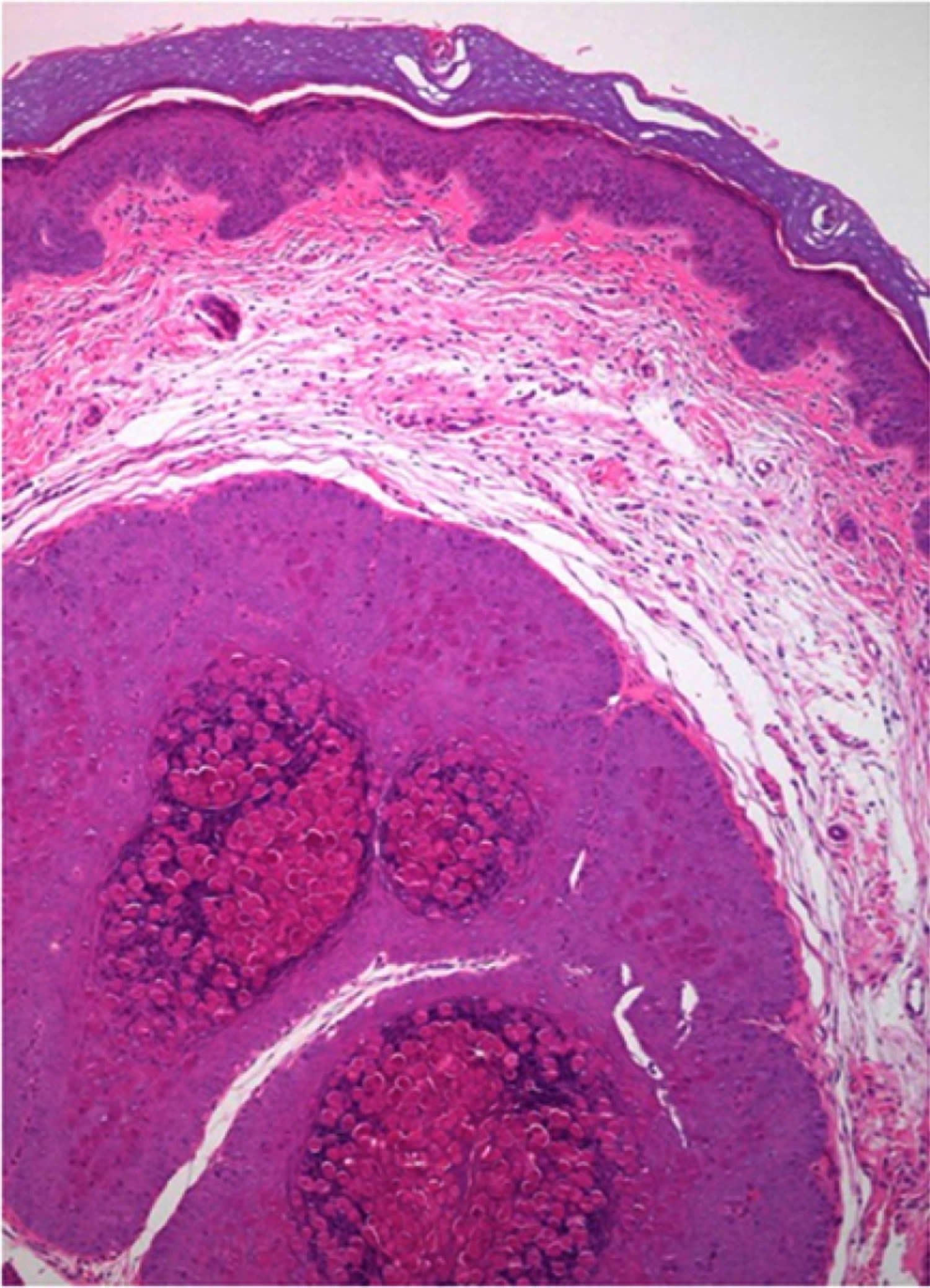

Very rarely, a biopsy is required. Histopathology shows characteristic intracytoplasmic eosinophil inclusion bodies known as Henderson-Petterson bodies (Figure 5).

Figure 4. Molluscum contagiosum dermatoscopic findings

Footnote: Polarized-light dermoscopy, original magnification 10×. Dermatoscopic findings of molluscum contagiosum. (Red arrows) white-to-yellow polylobular structures. (Blue arrows) crown vessels.

[Source 4 ]Figure 5. Molluscum contagiosum histopathology

Footnote: Molluscum contagiosum histopathology showing large intracytoplasmic eosinophil inclusion bodies called Henderson-Petterson bodies.

[Source 4 ]Molluscum contagiosum differential diagnosis

Molluscum contagiosum differential diagnoses include mainly inflammatory, infectious, and neoplastic etiologies; they mainly differ according to the age and immunologic status of the patient 2. In immunosuppressed patients, the main differential diagnosis includes histoplasmosis and cryptococcosis which can be seen as umbilicated papules 45.

Molluscum contagiosum differential diagnosis 2, 46, 47, 48, 49, 50, 15, 51:

- Infections

- Tumors

- Miscellaneous

- Papular urticaria

Molluscum contagiosum treatment

Molluscum contagiosum viral skin infection will resolve on its own within a few months. Talk to your child’s doctor about whether he or she recommends treatment or watchful waiting. No treatment is 100% effective since scientists are currently unable to kill the virus, and most can have side effects such as pain or irritation of the skin.

There is a consensus among experts that molluscum contagiosum treatment should be indicated in patients with extensive disease, secondary complications (bacterial superinfection, molluscum dermatitis, conjunctivitis), or aesthetic complaints 2.

Treatment for molluscum is usually recommended if lesions are in the genital area (on or near the penis, vulva, vagina, or anus) 52. If lesions are found in this area it is a good idea to visit your healthcare provider as there is a possibility that you may have another disease spread by sexual contact.

A retrospective study 53 evaluated the resolution rate of molluscum contagiosum lesions in treated and untreated patients, showing a resolution at 12 months of 45.6% in the treated group and 48.8% in the untreated group. At 18 months, they found a resolution rate of 69.5% and 72.6% in the treated versus the untreated group, respectively. From this cardinal study 53, it appears that active treatment does not improve the resolution rate when compared to observation alone.

- Be aware that some treatments available through the internet may not be effective and may even be harmful.

What are the treatment options for molluscum contagiosum?

Because molluscum contagiosum is self-limited in healthy individuals, treatment may be unnecessary. Nonetheless, issues such as lesion visibility, underlying atopic disease, and the desire to prevent transmission may prompt therapy.

Active treatments can be classified as phyiscal removal, chemical, immunomodulatory, and antiviral 2.

Possible treatments include the following:

- Cantharidin 0.7% or 0.9% liquid – This is an extract from the blister beetle. It is applied to the lesions and then washed off in 2–6 hours. It is not for use on the face or genitals.

- Removal with freezing (cryosurgery), scraping (curettage), or burning (electrocautery) – All of these options may be painful.

- Salicylic acid

- Podofilox (Condylox®)

- Tretinoin (Retin-A®)

- Trichloroacetic acid

- Silver nitrate paste

- Imiquimod cream (Aldara®) – This may be useful for widespread, difficult-to-treat lesions.

Physical removal

Physical removal of lesions may include cryotherapy (freezing the lesion with liquid nitrogen), curettage (the piercing of the core and scraping of caseous or cheesy material), and laser therapy. These options are rapid and require a trained health care provider, may require local anesthesia, and can result in post-procedural pain, irritation, and scarring.

- It is not a good idea to try and remove lesions or the fluid inside of lesions yourself. By removing lesions or lesion fluid by yourself you may unintentionally autoinoculate other parts of your body or risk spreading it to others. By scratching or scraping your skin you could cause a bacterial infection.

Cryotherapy is an effective treatment. It can be applied with a cotton-tipped swab or by portable sprayers, 1 or 2 cycles of 10 to 20 seconds are typically used 3. A prospective, randomized and comparative trial 54 evaluated the efficacy of cryotherapy in molluscum contagiosum treatment. The study demonstrated a complete clearance in 70.7% of the patients at 3 weeks and in 100% of them at 16 weeks 54. Another study 55 showed full clearance in 83.3% of 60 patients (average age of 20 years) at 6 weeks. In both, the application of cryotherapy was administered weekly. The disadvantages of cryotherapy are the possibility of blistering, scarring, and post-inflammatory hypo or hyperpigmentation 3.

Curettage is also an effective method and involves the physical removal of skin lesions 3. One study showed that of 1,879 children, 70% were cured with one session while 26% needed two sessions, with overall satisfaction of 97% in both parents and children 56. A randomized, controlled trial 57 showed a complete clearance with only one curettage session in 80.3% of the patients and without recurrences at 6 months of follow-up. It can be done with a curette, punch biopsy or with an ear speculum 58, 59. To reduce pain, topical application of EMLA (eutectic mixture of local anesthetics), a combination of 2.5% lidocaine and 2.5% prilocaine, may be required 1 hour before the procedure 56, 60. Curettage can cause pain, bleeding, and scarring.

After curettage, topical povidone iodine can be applied. This is an antiseptic useful in the treatment of molluscum contagiosum based on case reports 61. A Cochrane systematic review of 2017 showed that povidone-iodine 10% potentiates the effect of 50% salicylic acid, without adverse effects reported 21. For topical povidone iodine, an application scheme of 3 times a day until the resolution of the cutaneous lesions.

Another useful mechanical method is pulse dye laser therapy, which due to its costs and limited availability is suggested to be left for refractory cases 62, 2. It is an effective, safe, and well-tolerated treatment, with infrequent adverse effects 62. Cases of successful use in immunosuppressed patients have also been reported 63.

Oral therapy

Gradual removal of lesions may be achieved by oral therapy. This technique is often desirable for children because it is generally less painful and may be performed by parents at home in a less threatening environment. Oral cimetidine has been used as an alternative treatment for small children who are either afraid of the pain associated with cryotherapy, curettage, and laser therapy or because the possibility of scarring is to be avoided. Oral cimetidine is an H2 (histamine-2) receptor antagonist that would stimulate the delayed hypersensitivity response 3.

While cimetidine is safe, painless, and well tolerated and the recommended dose is 25–40 mg/kg/day, facial molluscum contagiosum do not respond as well as lesions elsewhere on the body 2.

Topical therapy

Topical therapy destroy skin lesions through the inflammatory response they produce. Podophyllotoxin cream (0.5%) is reliable as a home therapy for men but is not recommended for pregnant women because of presumed toxicity to the fetus. Each lesion must be treated individually as the therapeutic effect is localized. Other options for topical therapy include iodine and trichloroacetic acid, salicylic acid, lactic acid, glycolic acid, benzoyl peroxide, potassium hydroxide (KOH), tretinoin, cantharidin (a blistering agent usually applied in an office setting), and imiquimod (T cell modifier) 2, 3, 61. These treatments must be prescribed by a health care professional.

Cantharidin is a topical agent, an inhibitor of phosphodiesterase, which produces an intraepidermal blister, followed by resolution of the lesion and healing without a scar in some cases 64. The efficacy of cantharidin in the treatment of molluscum contagiosum is variable, with cure rates varying between 15.4% and 100% among the different studies 65, 66. It is recommended to apply cantharidin 0.7–0.9% at the site of the lesion, with or without occlusion, and to wash with soap and water 2–4 hours later, each every 2–4 weeks until the resolution of lesions 3, 57, 64. In the face and anogenital region it should be used with precaution due to the risk of bacterial superinfection of blisters that form after 24–48 hours 3, 67.

Potassium hydroxide (KOH) is an alkaline compound that dissolves keratin 3. Potassium hydroxide (KOH) has been used in concentrations and therapeutic schemes that vary from 5% to 20%, two times a day or every other day for 1 week or until inflammation develops 68. A recent study 69 showed that 10% and 15% potassium hydroxide clear lesions of molluscum contagiosum entirely in 58.8% and 64.3% of the patients, respectively. It would be a safe and effective treatment that could be applied by patients, and its effectiveness has been compared with cryotherapy and imiquimod without significant differences 68, 70.

Immunomodulatory methods

Immunomodulatory methods stimulate the patient’s immune response against the infection. Imiquimod is an immune-stimulatory agent agonist of the toll-like receptor 7 that activates the innate and acquired immune response 3. Imiquimod is a useful alternative in the treatment of molluscum contagiosum based on case reports and uncontrolled studies 22, 71. However, imiquimod has not been proven effective for the treatment of molluscum contagiosum in children and is not recommended for children due to possible adverse events 72.

A prospective, randomized trial 54 compared the efficacy of cryotherapy with 5% imiquimod, demonstrating a complete clearance in 100% of the patients at 16 weeks for cryotherapy versus 92% for imiquimod 5% (difference not statistically significant). Cutaneous adverse effects were more frequent in the cryotherapy group. However, a recent Cochrane systematic review showed that it is not better than placebo in short-term improvement (3 months) or long-term cure (more than 6 months) and may produce adverse effects at the application site such as pain, blistering, scars and/or pigmentary changes 21. The current evidence positions imiquimod as a controversial therapeutic alternative 73.

Other immunomodulatory methods are oral cimetidine, interferon alfa, candidin, and diphencyprone.

Candidin is intralesional immunotherapy derived from the purified extract of Candida albicans. It is an alternative in the treatment of molluscum contagiosum, being applied purely or diluted at 50% with lidocaine in a dose of 0.2–0.3 mL intralesional every 3 weeks 3. A retrospective study evaluating the efficacy of candidin in the treatment of molluscum contagiosum showed a complete resolution rate of 55% and a partial resolution of 37.9%, with an overall response rate of 93% 74.

Diphencyprone is a topical immunomodulator used in multiple skin diseases. Cases of successful treatment with diphencyprone have been reported in immunosuppressed and immunocompetent patients 75, 76.

Therapy for immunocompromised persons

Most therapies are effective in immunocompetent patients; however, patients with HIV and AIDS or other immunosuppressing conditions often do not respond to traditional treatments. In addition, these treatments are largely ineffective in achieving long-term control in HIV patients.

Low CD4 cell counts have been linked to widespread facial mollusca and therefore have become a marker for severe HIV disease. Thus far, therapies targeted at boosting the immune system have proven the most effective therapy for molluscum contagiosum in immunocompromised persons. In extreme cases, intralesional interferon alfa has been used to treat facial lesions in these patients. Interferon alfa is a proinflammatory cytokine that is used in the treatment of molluscum contagiosum in immunosuppressed patients with severe or refractory disease. It can be administered subcutaneously or intralesionally 77, 78, 79. However, the severe and unpleasant side effects of interferon, such as influenza-like symptoms, site tenderness, depression, and lethargy, make it a less-than-desirable treatment. Furthermore, interferon therapy proved most effective in otherwise healthy persons.

Another method used in immunosuppressed patients with extensive or refractory disease is cidofovir, an antiviral drug initially used in cytomegalovirus retinitis in HIV patients. It can be used topically at a concentration of 1–3% or intravenously 80, 81, 82. The major problem with intravenous administration is nephrotoxicity 83.

Radiation therapy is also of little benefit.

New therapies

New molluscum contagiosum treatments include topical sinecatechins 84, intralesional 5-fluorouracil (5 FU) 85, hyperthermia 86 and zoster immune globulin (ZIG) 87. Evidence is preliminary to determine the effectiveness of these therapies.

What are the long-term effects of molluscum contagiosum?

In immune competent hosts, molluscum contagiosum is a relatively harmless. The papules may persist for up to 2 years or longer. In children, about half of cases have cleared by 12 months, and two-thirds by 18 months, with or without treatment. Contact with another infected individual later on can lead to a new crop of mollusca.

Infection can be very persistent in the presence of significant immune deficiency.

Molluscum contagiosum doesn’t usually cause any long-term problems. The growths typically don’t leave any marks. Treatments might scar the skin, though, and some people develop an infection that needs to be treated with antibiotics.

Recovery from one molluscum infection does not prevent future infections. Molluscum contagiosum is not like herpes viruses which can remain dormant (“sleeping”) in your body for long periods of time and then reappear. If you get new molluscum contagiosum lesions after you are cured, it means you have come in contact with an infected person or object again.

Complications of molluscum contagiosum

The lesions caused by molluscum contagiosum are usually benign and resolve without scarring. However scratching at the lesion, or using scraping and scooping to remove the lesion, can cause scarring. For this reason, physically removing the lesion is not often recommended in otherwise healthy individuals.

The most common complication is a secondary infection caused by bacteria. Secondary infections may be a significant problem in immunocompromised patients, such as those with HIV/AIDS or those taking immunosuppressing drug therapies. In these cases, treatment to prevent further spread of the infection is recommended.

Molluscum contagiosum prognosis

In immunecompetent hosts, molluscum contagiosum is relatively harmless with lesions resolving without scarring. The papules may persist for up to 2 years or longer. In children, about half of cases have cleared by 12 months, and two-thirds by 18 months, with or without treatment. Contact with another infected individual later on can lead to a new crop. However scratching at the lesion, or using scraping and scooping to remove the lesion, can cause scarring. For this reason, physically removing molluscum contagiosum is not often recommended in otherwise healthy individuals.

Infection can be very persistent in the presence of significant immune deficiency. The most common complication is a secondary infection caused by bacteria. Secondary infections may be a significant problem in immunocompromised patients, such as those with HIV/AIDS or those taking immunosuppressing drug therapies. In these cases, treatment to prevent further spread of the infection is recommended. In people living with HIV/AIDS, molluscum contagiosum is best managed with highly active antiretroviral therapy (HAART) 88.

References- Molluscum Contagiosum. https://www.cdc.gov/poxvirus/molluscum-contagiosum/index.html

- Leung AKC, Barankin B, Hon KLE. Molluscum contagiosum: an update. Recent Pat Inflamm Allergy Drug Discov. 2017;11(1):22–31. doi: 10.2174/1872213X11666170518114456

- Gerlero P, Hernandez-Martin A. Update on the treatment of molluscum contagiosum in children. Actas Dermosifiliogr. 2018;109(5):408–415. doi: 10.1016/j.ad.2018.01.007

- Meza-Romero R, Navarrete-Dechent C, Downey C. Molluscum contagiosum: an update and review of new perspectives in etiology, diagnosis, and treatment. Clin Cosmet Investig Dermatol. 2019 May 30;12:373-381. doi: 10.2147/CCID.S187224

- Rogers M, Barnetson RSC. Diseases of the skin. In: Campbell AGM, McIntosh N, et al. editor(s). Forfar and Arneil’s Textbook of Pediatrics. 5th Edition. New York: Churchill Livingstone, 1998:1633–5.

- Peterson AR, Nash E, Anderson BJ. Infectious disease in contact sports. Sports Health. 2019;11(1):47–58. doi: 10.1177/1941738118789954

- Koopman RJ, van Merriënboer FC, Vreden SG, Dolmans WM. Molluscum contagiosum; a marker for advanced HIV infection. Br J Dermatol. 1992 May;126(5):528-9. doi: 10.1111/j.1365-2133.1992.tb11835.x

- Czelusta A, Yen-Moore A, Van der Straten M, Carrasco D, Tyring SK. An overview of sexually transmitted diseases. Part III. Sexually transmitted diseases in HIV-infected patients. J Am Acad Dermatol. 2000;43(3):409–432; quiz 33-6 DOI: 10.1067/mjd.2000.105158

- Kaufman WS, Ahn CS, Huang WW. Molluscum contagiosum in immunocompromised patients: AIDS presenting as molluscum contagiosum in a patient with psoriasis on biologic therapy. Cutis. 2018 Feb;101(2):136-140. https://cdn.mdedge.com/files/s3fs-public/Document/February-2018/CT101002136.PDF

- Olsen JR, Gallacher J, Piguet V, Francis NA. Epidemiology of molluscum contagiosum in children: a systematic review. Fam Pract. 2014;31(2):130–136. doi: 10.1093/fampra/cmt075

- Dohil MA, Lin P, Lee J, Lucky AW, Paller AS, Eichenfield LF. The epidemiology of molluscum contagiosum in children. J Am Acad Dermatol. 2006;54(1):47–54. doi: 10.1016/j.jaad.2005.08.035

- Olsen JR, Piguet V, Gallacher J, Francis NA. Molluscum contagiosum and associations with atopic eczema in children: a retrospective longitudinal study in primary care. Br J Gen Pract. 2016;66(642):e53–e58. doi: 10.3399/bjgp15X688093

- Silverberg NB. Molluscum contagiosum virus infection can trigger atopic dermatitis disease onset or flare. Cutis. 2018 Sep;102(3):191-194. https://cdn.mdedge.com/files/s3fs-public/Document/August-2018/CT102003191.PDF

- Braue A, Ross G, Varigos G, Kelly H. Epidemiology and impact of childhood molluscum contagiosum: a case series and critical review of the literature. Pediatr Dermatol. 2005;22(4):287–294. doi: 10.1111/j.1525-1470.2005.22401.x

- Berger EM, Orlow SJ, Patel RR, Schaffer JV. Experience with molluscum contagiosum and associated inflammatory reactions in a pediatric dermatology practice: the bump that rashes. Arch Dermatol. 2012;148(11):1257–1264. doi: 10.1001/archdermatol.2012.2414

- Manti S, Amorini M, Cuppari C, et al. Filaggrin mutations and Molluscum contagiosum skin infection in patients with atopic dermatitis. Ann Allergy Asthma Immunol. 2017;119(5):446–451. doi: 10.1016/j.anai.2017.07.019

- Hayashida S, Furusho N, Uchi H, et al. Are lifetime prevalence of impetigo, molluscum and herpes infection really increased in children having atopic dermatitis? J Dermatol Sci. 2010;60(3):173–178. doi: 10.1016/j.jdermsci.2010.09.003

- Basu S, Kumar A. Giant molluscum contagiosum – a clue to the diagnosis of human immunodeficiency virus infection. J Epidemiol Glob Health. 2013;3(4):289–291. doi: 10.1016/j.jegh.2013.06.002

- Vora RV, Pilani AP, Kota RK. Extensive giant molluscum contagiosum in a HIV positive patient. J Clin Diagn Res. 2015;9(11):Wd01–wd02. doi: 10.7860/JCDR/2015/15107.6797

- Husak R, Garbe C, Orfanos CE. [Mollusca contagiosa in HIV infection. Clinical manifestation, relation to immune status and prognostic value in 39 patients]. Hautarzt. 1997;48(2):103–109. doi: 10.1007/s001050050554

- van der Wouden JC, van der Sande R, Kruithof EJ, Sollie A, van Suijlekom-Smit LW, Koning S. Interventions for cutaneous molluscum contagiosum. Cochrane Database Syst Rev. 2017 May 17;5(5):CD004767. doi: 10.1002/14651858.CD004767.pub4

- Butala N, Siegfried E, Weissler A. Molluscum BOTE sign: a predictor of imminent resolution. Pediatrics. 2013;131(5):e1650–e1653. doi: 10.1542/peds.2012-2933

- Trcko K, Hosnjak L, Kusar B, et al. Clinical, histopathological, and virological evaluation of 203 patients with a clinical diagnosis of molluscum contagiosum. Open Forum Infect Dis. 2018;5(11):ofy298. doi: 10.1093/ofid/ofy298

- Chen X, Anstey AV, Bugert JJ. Molluscum contagiosum virus infection. Lancet Infect Dis. 2013;13(10):877–888. doi: 10.1016/S1473-3099(13)70109-9

- Zorec TM, Kutnjak D, Hosnjak L, et al. New Insights into the evolutionary and genomic landscape of Molluscum Contagiosum Virus (MCV) based on nine MCV1 and six MCV2 complete genome sequences. Viruses. 2018;10(11). doi: 10.3390/v10110586

- Brady G, Haas DA, Farrell PJ, Pichlmair A, Bowie AG. Molluscum contagiosum virus protein MC005 inhibits NF-kappaB activation by targeting NEMO-regulated IkappaB kinase activation. J Virol. 2017;91(15). doi: 10.1128/JVI.00955-17

- Shisler JL. Immune evasion strategies of molluscum contagiosum virus. Adv Virus Res. 2015;92:201–252. doi: 10.1016/bs.aivir.2014.11.004

- Biswas S, Smith GL, Roy EJ, Ward B, Shisler JL. A comparison of the effect of molluscum contagiosum virus MC159 and MC160 proteins on vaccinia virus virulence in intranasal and intradermal infection routes. J Gen Virol. 2018;99(2):246–252. doi: 10.1099/jgv.0.001006

- Brady G, Haas DA, Farrell PJ, Pichlmair A, Bowie AG. Poxvirus protein MC132 from molluscum contagiosum virus inhibits NF-B activation by targeting p65 for degradation. J Virol. 2015;89(16):8406–8415. doi: 10.1128/JVI.00799-15

- Gurtler C, Bowie AG. Innate immune detection of microbial nucleic acids. Trends Microbiol. 2013;21(8):413–420. doi: 10.1016/j.tim.2013.04.004

- Molluscum contagiosum. https://dermnetnz.org/topics/molluscum-contagiosum

- Berbegal-DeGracia L, Betlloch-Mas I, DeLeon-Marrero FJ, Martinez-Miravete MT, Miralles-Botella J. Neonatal Molluscum contagiosum: five new cases and a literature review. Australas J Dermatol. 2015;56(2):e35–e38. doi: 10.1111/ajd.12127

- Mira-Perceval Juan G, Alcala Minagorre PJ, Betlloch Mas I, Sanchez Bautista A. [Molluscum contagiosum due to vertical transmission]. An Esp Pediatr. 2017;86(5):292–293. doi: 10.1016/j.anpedi.2015.12.014

- Ives C, Green M, Wright T. Molluscum contagiosum: a rare nipple lesion. Breast J. 2017;23(1):107–108. doi: 10.1111/tbj.12693

- Hoyt BS, Tschen JA, Cohen PR. Molluscum contagiosum of the areola and nipple: case report and literature review. Dermatol Online J. 2013 Jul 14;19(7):18965. https://doi.org/10.5070/D3197018965

- Ringeisen AL, Raven ML, Barney NP. Bulbar conjunctival molluscum contagiosum. Ophthalmology. 2016;123(2):294. doi: 10.1016/j.ophtha.2015.11.022

- Ma H, Yang H, Zhou Y, Jiang L. Molluscum contagiosum on the lip. J Craniofac Surg. 2015;26(7):e681–e682. doi: 10.1097/SCS.0000000000002187

- Serin S, Bozkurt Oflaz A, Karabagli P, Gedik S, Bozkurt B. Eyelid molluscum contagiosum lesions in two patients with unilateral chronic conjunctivitis. Turk Oftalmol Derg. 2017;47(4):226–230. doi: 10.4274/tjo.52138

- Kim HK, Jang WS, Kim BJ, Kim MN. Rare manifestation of giant molluscum contagiosum on the scalp in old age. Ann Dermatol. 2013;25(1):109–110. doi: 10.5021/ad.2013.25.1.109

- Rosner M, Zloto O. Periocular molluscum contagiosum: six different clinical presentations. Acta Ophthalmol (Copenh). 2018;96(5):e600–e5. doi: 10.1111/aos.13717

- Schornack MM, Siemsen DW, Bradley EA, Salomao DR, Lee HB. Ocular manifestations of molluscum contagiosum. Clin Exp Optom. 2006;89(6):390–393. doi: 10.1111/cxo.2006.89.issue-6

- Schaffer JV, Berger EM. Molluscum contagiosum. JAMA Dermatol. 2016;152(9):1072. doi: 10.1001/jamadermatol.2016.2344

- Fornatora ML, Reich RF, Gray RG, Freedman PD. Intraoral molluscum contagiosum: a report of a case and a review of the literature. Oral Surg Oral Med Oral Pathol Oral Radiol Endod. 2001;92(3):318–320. doi: 10.1067/moe.2001.117299

- Brown, J., Janniger, C.K., Schwartz, R.A. and Silverberg, N.B. (2006), Childhood molluscum contagiosum. International Journal of Dermatology, 45: 93-99. https://doi.org/10.1111/j.1365-4632.2006.02737.x

- Patrick Blanco, Jean-François Viallard, Marie Beylot Barry, Isabelle Faure, Patrick Mercié, Vergier Béatrice, Jean-Luc Pellegrin, Bernard Leng, Cutaneous Cryptococcosis Resembling Molluscum Contagiosum in a Patient with Non-Hodgkin’s Lymphoma, Clinical Infectious Diseases, Volume 29, Issue 3, September 1999, Pages 683–684, https://doi.org/10.1086/598655

- Leung AKBB. Nasal verrucae vulgaris: an uncommon finding. Scholars J Med Case Rep. 2015;11:1036–1037.

- Leung, A.K.C., Kao, C.P. and Sauve, R.S. (2001), Scarring Resulting from Chickenpox. Pediatric Dermatology, 18: 378-380. https://doi.org/10.1046/j.1525-1470.2001.01975.x

- Stamm AW, Kobashi KC, Stefanovic KB. Urologic dermatology: a review. Curr Urol Rep. 2017;18(8):62. doi: 10.1007/s11934-017-0712-9

- Mizuashi M, Tamabuchi T, Tagami H, Aiba S. Focal presence of molluscum contagiosum in basal cell carcinoma. Eur J Dermatol. 2012;22(3):424–425. doi: 10.1684/ejd.2012.1699

- Hon KLLA. Acne: Causes, Treatment and Myths. New York: Nova Science Publishers, Inc.; 2010:1–89.

- Paolino G, Muscardin LM, Panetta C, Donati M, Donati P. Linear ectopic sebaceous hyperplasia of the penis: the last memory of Tyson’s glands. G Ital Dermatol Venereol. 2018;153(3):429–431. doi: 10.23736/S0392-0488.16.05129-4

- Molluscum Contagiosum. https://www.cdc.gov/poxvirus/molluscum-contagiosum/treatment.html

- Basdag H, Rainer BM, Cohen BA. Molluscum contagiosum: to treat or not to treat? Experience with 170 children in an outpatient clinic setting in the northeastern United States. Pediatr Dermatol. 2015;32(3):353–357. doi: 10.1111/pde.12504

- Al-Mutairi N, Al-Doukhi A, Al-Farag S, Al-Haddad A. Comparative study on the efficacy, safety, and acceptability of imiquimod 5% cream versus cryotherapy for molluscum contagiosum in children. Pediatr Dermatol. 2010;27(4):388–394. doi: 10.1111/j.1525-1470.2009.00974.x

- Qureshi A, Zeb M, Jalal-Ud-Din M, Sheikh ZI, Alam MA, Anwar SA. Comparison Of Efficacy Of 10% Potassium Hydroxide Solution Versus Cryotherapy In Treatment Of Molluscum Contagiosum. J Ayub Med Coll Abbottabad. 2016 Apr-Jun;28(2):382-385. https://jamc.ayubmed.edu.pk/jamc/index.php/jamc/article/view/1103/303

- Harel A, Kutz AM, Hadj-Rabia S, Mashiah J. To treat molluscum contagiosum or not-curettage: an effective, well-accepted treatment modality. Pediatr Dermatol. 2016;33(6):640–645. doi: 10.1111/pde.12968

- Hanna D, Hatami A, Powell J, et al. A prospective randomized trial comparing the efficacy and adverse effects of four recognized treatments of molluscum contagiosum in children. Pediatr Dermatol. 2006;23(6):574–579. doi: 10.1111/j.1525-1470.2006.00313.x

- Kelly V, Coulombe J, Lavoie I. Use of a disposable ear speculum: an alternative technique for molluscum contagiosum curettage. Pediatr Dermatol. 2018;35(3):418–419. doi: 10.1111/pde.13453

- Navarrete-Dechent C-M-M, Droppelmann N, González S. Actualización en el uso de la biopsia de piel por punch. Revista Chilena De Cirugía. 2016;68:467–473. doi: 10.1016/j.rchic.2016.05.008

- Gobbato AA, Babadopulos T, Gobbato CA, Moreno RA, Gagliano-Juca T, De Nucci G. Tolerability of 2.5% lidocaine/prilocaine hydrogel in children undergoing cryotherapy for molluscum contagiosum. Pediatr Dermatol. 2016;33(3):e214–e215. doi: 10.1111/pde.12842

- Capriotti K, Stewart K, Pelletier J, Capriotti J. Molluscum Contagiosum Treated with Dilute Povidone-Iodine: A Series of Cases. J Clin Aesthet Dermatol. 2017 Mar;10(3):41-45. https://www.ncbi.nlm.nih.gov/pmc/articles/PMC5367881

- Griffith RD, Yazdani Abyaneh MA, Falto-Aizpurua L, Nouri K. Pulsed dye laser therapy for molluscum contagiosum: a systematic review. J Drugs Dermatol. 2014 Nov;13(11):1349-52. https://jddonline.com/articles/pulsed-dye-laser-therapy-for-molluscum-contagiosum-a-systematic-review-S1545961614P1349X/

- Fisher C, McLawhorn JM, Adotama P, Stasko T, Collins L, Levin J. Pulsed dye laser repurposed: treatment of refractory molluscum contagiosum in renal transplant patient. Transpl Infect Dis. 2019;21(2):e13036. doi: 10.1111/tid.2019.21.issue-2

- Moye V, Cathcart S, Burkhart CN, Morrell DS. Beetle juice: a guide for the use of cantharidin in the treatment of molluscum contagiosum. Dermatol Ther. 2013;26(6):445–451. doi: 10.1111/dth.12105

- Vakharia PP, Chopra R, Silverberg NB, Silverberg JI. Efficacy and safety of topical cantharidin treatment for molluscum contagiosum and warts: a systematic review. Am J Clin Dermatol. 2018;19(6):791–803. doi: 10.1007/s40257-018-0375-4

- Ting, P.T. and Dytoc, M.T. (2004), Therapy of external anogenital warts and molluscum contagiosum: a literature review. Dermatologic Therapy, 17: 68-101. https://doi.org/10.1111/j.1396-0296.2004.04009.x

- Rush J, Dinulos JG. Childhood skin and soft tissue infections: new discoveries and guidelines regarding the management of bacterial soft tissue infections, molluscum contagiosum, and warts. Curr Opin Pediatr. 2016;28(2):250–257. doi: 10.1097/MOP.0000000000000334

- Can B, Topaloglu F, Kavala M, Turkoglu Z, Zindanci I, Sudogan S. Treatment of pediatric molluscum contagiosum with 10% potassium hydroxide solution. J Dermatolog Treat. 2014;25(3):246–248. doi: 10.3109/09546634.2012.697988

- Teixido C, Diez O, Marsal JR, et al. Efficacy and safety of topical application of 15% and 10% potassium hydroxide for the treatment of Molluscum contagiosum. Pediatr Dermatol. 2018;35(3):336–342. doi: 10.1111/pde.13438

- Metkar A, Pande S, Khopkar U. An open, nonrandomized, comparative study of imiquimod 5% cream versus 10% potassium hydroxide solution in the treatment of molluscum contagiosum. Indian J Dermatol Venereol Leprol. 2008 Nov-Dec;74(6):614-8. doi: 10.4103/0378-6323.45104

- Skinner RB Jr. Treatment of molluscum contagiosum with imiquimod 5% cream. J Am Acad Dermatol. 2002 Oct;47(4 Suppl):S221-4. doi: 10.1067/mjd.2002.126578

- Molluscum Contagiosum Treatment Options. https://www.cdc.gov/poxvirus/molluscum-contagiosum/treatment.html

- Katz KA, Williams HC, van der Wouden JC. Imiquimod cream for molluscum contagiosum: neither safe nor effective. Pediatr Dermatol. 2018;35(2):282–283. doi: 10.1111/pde.13398

- Enns LL, Evans MS. Intralesional immunotherapy with Candida antigen for the treatment of molluscum contagiosum in children. Pediatr Dermatol. 2011;28(3):254–258. doi: 10.1111/j.1525-1470.2011.01492.x

- Chularojanamontri L, Tuchinda P, Kulthanan K, Manuskiatti W. Generalized molluscum contagiosum in an HIV patient treated with diphencyprone. J Dermatol Case Rep. 2010;4(4):60–62. doi: 10.3315/jdcr.2010.1059

- Kang SH, Lee D, Hoon Park J, Cho SH, Lee SS, Park SW. Treatment of molluscum contagiosum with topical diphencyprone therapy. Acta Derm Venereol. 2005;85(6):529–530. doi: 10.1080/00015550510034948

- Bohm M, Luger TA, Bonsmann G. Disseminated giant molluscum contagiosum in a patient with idiopathic CD4+ lymphocytopenia successful eradication with systemic interferon. Dermatology. 2008;217(3):196–198. doi: 10.1159/000141649

- Kilic SS, Kilicbay F. Interferon-alpha treatment of molluscum contagiosum in a patient with hyperimmunoglobulin E syndrome. Pediatrics. 2006;117(6):e1253–e1255. doi: 10.1542/peds.2005-2706

- Nelson MR, Chard S, Barton SE. Intralesional interferon for the treatment of recalcitrant molluscum contagiosum in HIV antibody positive individuals–a preliminary report. Int J STD AIDS. 1995;6(5):351–352. doi: 10.1177/095646249500600509

- Erickson C, Driscoll M, Gaspari A. Efficacy of intravenous cidofovir in the treatment of giant molluscum contagiosum in a patient with human immunodeficiency virus. Arch Dermatol. 2011;147(6):652–654. doi: 10.1001/archdermatol.2011.20

- Foissac M, Goehringer F, Ranaivo IM, et al. [Efficacy and safety of intravenous cidofovir in the treatment of giant molluscum contagiosum in an immunosuppressed patient]. Ann Dermatol Venereol. 2014;141(10):620–622. doi: 10.1016/j.annder.2014.04.114

- Toro JR, Wood LV, Patel NK, Turner ML. Topical cidofovir: a novel treatment for recalcitrant molluscum contagiosum in children infected with human immunodeficiency virus 1. Arch Dermatol. 2000 Aug;136(8):983-5. doi: 10.1001/archderm.136.8.983. Erratum in: Arch Dermatol 2002 Feb;138(2):257.

- Vora SB, Brothers AW, Englund JA. Renal toxicity in pediatric patients receiving cidofovir for the treatment of adenovirus infection. J Pediatric Infect Dis Soc. 2017;6(4):399–402. doi: 10.1093/jpids/pix011

- Padilla Espana L, Mota-Burgos A, Martinez-Amo JL, Benavente-Ortiz F, Rodriguez-Bujaldon A, Hernandez-Montoya C. Recalcitrant molluscum contagiosum successfully treated with sinecatechins. Dermatol Ther. 2016;29(4):217–218. doi: 10.1111/dth.12338

- Viswanath V, Shah RJ, Gada JL. Intralesional 5-fluorouracil: novel therapy for extensive molluscum contagiosum in an immunocompetent adult. Indian J Dermatol Venereol Leprol. 2017;83(2):265–266. doi: 10.4103/0378-6323.193626

- Gao YL, Gao XH, Qi RQ, et al. Clinical evaluation of local hyperthermia at 44 degrees C for molluscum contagiosum: pilot study with 21 patients. Br J Dermatol. 2017;176(3):809–812. doi: 10.1111/bjd.14849

- Maiolo C, Marshman G. Zoster immunoglobulin-VF: a potential treatment for molluscum contagiosum in immunosuppressed children. Pediatr Dermatol. 2015;32(4):e193. doi: 10.1111/pde.2015.32.issue-4

- Badri T, Gandhi GR. Molluscum Contagiosum. [Updated 2022 May 1]. In: StatPearls [Internet]. Treasure Island (FL): StatPearls Publishing; 2022 Jan-. Available from: https://www.ncbi.nlm.nih.gov/books/NBK441898