Odontogenic keratocyst

Odontogenic keratocyst (OKC) previously known as keratocyst odontogenic tumor (KOT), are benign cystic lesions involving the mandible or maxilla with aggressive behavior and a high recurrence rate and are believed to arise from cell rests of dental lamina 1. Odontogenic keratocyst (OKC) can occur anywhere in the jaw, but commonly seen in the posterior part of the mandible. While the KOT tumor is generally regarded as an intraosseous lesion, rare peripheral cases have been reported. The majority of cases involve the gingival or alveolar mucosa in the canine-premolar region 2. Whether odontogenic keratocysts are developmental or neoplastic is controversial, with the 2017 World Health Organization (WHO) classification placing it back into the developmental cystic lesion of benign nature category, with a prevalence of 10% 3. Odontogenic keratocysts are locally aggressive and tend to recur after excision.

Odontogenic keratocysts could be diagnosed at any age; however, 60 % of cases occurred in individuals between 10 and 40 years of age 4, with OKC predominantly found in younger patients with a peak in the second and third decades 5. Furthermore, regarding the topographic sites for the occurrence of OKC, the majority of studies showed that odontogenic keratocysts were diagnosed mainly in the mandible body, ascending branch and mandibular angle 6. Odontogenic keratocyst may be seen in either the body or ramus of the mandible (~70% of all keratocystic odontic tumors) or maxilla comprising 5-10% of all jaw cysts 7. Payne 8 reported no differences with reference to predilection for gender in the clinical diagnosis of odontogenic keratocyst; whereas, Brannon 9 reported a certain predilection for the male gender.

On imaging, odontogenic keratocysts typically appear as an expansile solitary unilocular lesion extending longitudinally in the posterior portions of the mandible. Although the majority are solitary, in 5-10% of cases multiple odontogenic keratocysts will be present: an associated condition such as basal cell nevus syndrome should be considered in these cases. Radiographically, most OKCs are unilocular when presented at the periapex and can be mistaken for radicular or lateral periodontal cyst. When the cyst is multilocular and located at the molar ramus area, it may be confused to ameloblastoma. Lots of cases have been reported in the literature where OKC is associated with the nonvital tooth. So trauma could be one of the reasons in inducing this cyst.

OKC has a number of ‘compartments’ and has connecting smaller cysts that extend into the surrounding bone. Because of this, there is frequent tendency for the odontogenic keratocyst to recur, particularly if the original surgical treatment did not result in complete removal of the odontogenic keratocyst.

Conservative surgical management is the first choice and might be considered the gold standard, but combined therapy such as marsupialization, application of Carnoy’s solution, enucleation of the remnant lesion and an extensive follow-up period would considerably reduce recurrence rates 3. Removal of odontogenic keratocyst with removal of surrounding bone and/or cryosurgery (intense cold is applied to the cyst and bone) are the most common forms of treatment.

Long-term follow-up with monitoring by X-ray is important, as if these odontogenic keratocysts are left untreated, they can become quite large and locally destructive 10.

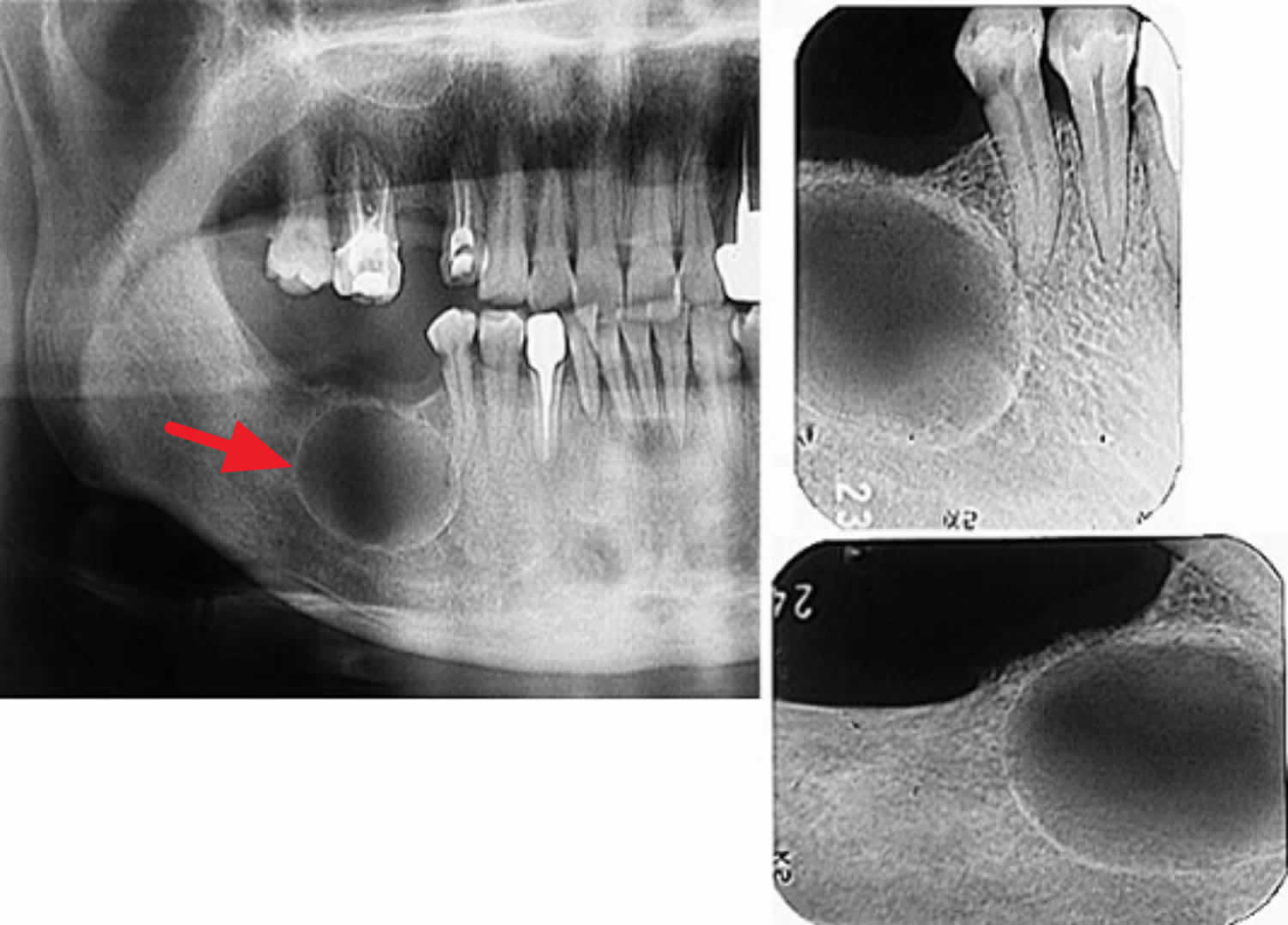

Figure 1. Odontogenic keratocyst

Footnote: Orthopantomograph shows multiple radiolucencies associated with mandibular anterior region, maxillary right and left as well as mandibular left impacted third molar teeth.

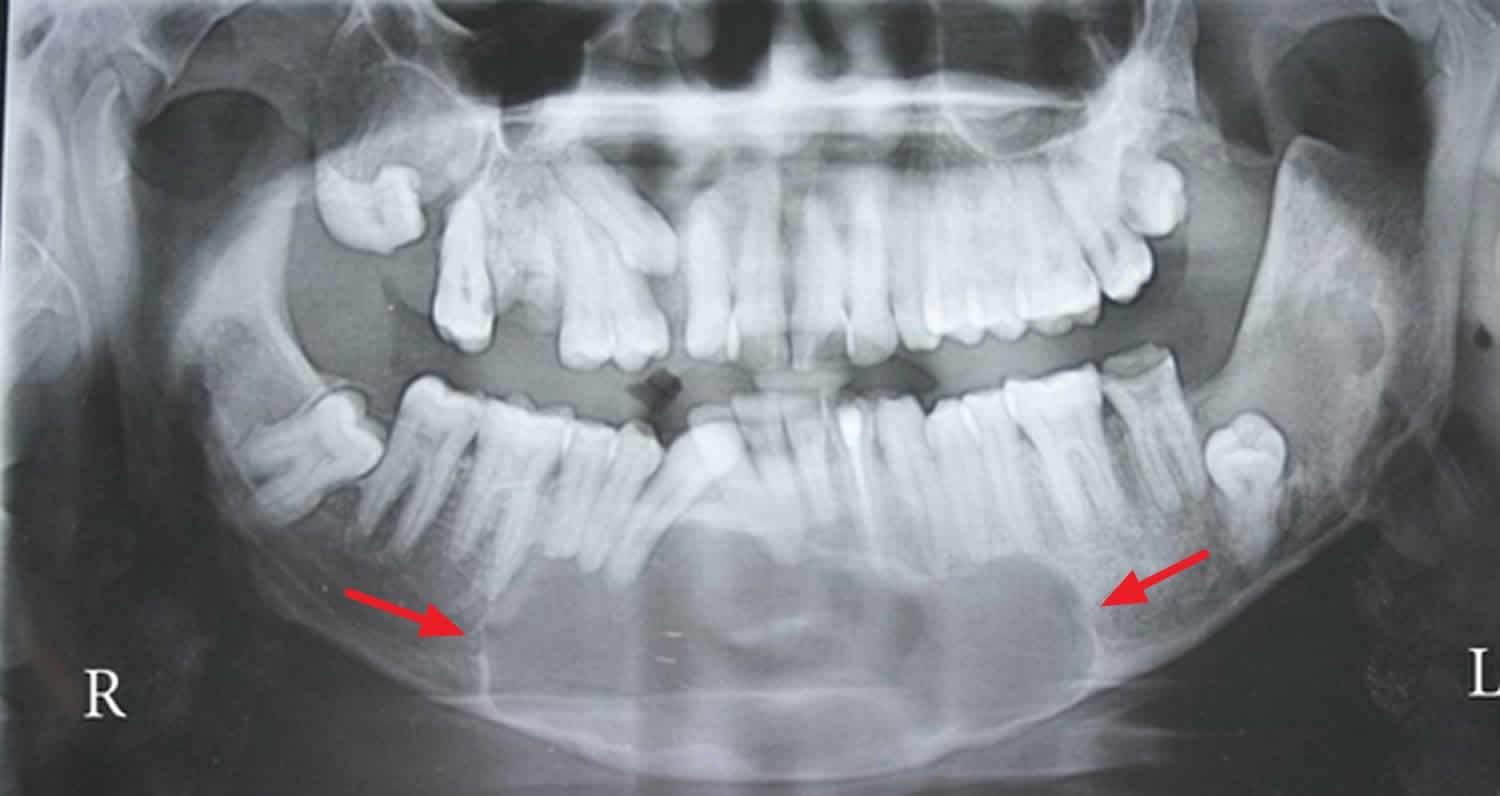

[Source 11 ]Figure 2. Maxillary odontogenic keratocyst

Footnote: Panoramic view showing unicystic radiolucency with sclerotic borders from the distal side of tooth 16 to the same side of tooth 22. In the interspace area between teeth 12 and 13, the lesion was completely extended to the alveolar ridge causing severe divergency of teeth 12 and 13. It was seen also the upper displacement of the right maxillary sinus floor and medial displacement of the nasal cavity floor and lateral wall.

[Source 12 ]Odontogenic keratocyst causes

Odontogenic keratocyst cause is controversial. One theory is that odontogenic keratocyst develops instead of a tooth. Neville and colleagues 13 stated that the OKC has an embryonic origin from the cellular remnants of the dental lamina. Presumably, the cells that would form the tooth undergo cystic degeneration without ever completing tooth formation and develop into the odontogenic keratocyst.

Odontogenic keratocyst symptoms

In the vast majority of OKC odontogenic keratocyst cases there are asymptomatic and are commonly discovered incidentally during routine imaging exams (orthopantomography or OPG) 3. When symptomatic, jaw swelling and pain are a common symptoms associated with odontogenic keratocysts 5. Occasionally, pain, swelling, and drainage will herald a secondary infection of the odontogenic keratocyst 5. Less commonly, trismus and paresthesia may occur.

In addition, the growth rate of this pathological condition is slow, and occurs in the anteroposterior direction, covering the medullary spaces of the bone. Consequently, in the majority of cases, in the initial stages, it is not possible to show it through the clinical finding of bone cortical swelling.

Odontogenic keratocyst diagnosis

In order to confirm the diagnosis of odontogenic keratocyst, it is necessary to perform a complete intra and extra-oral clinical evaluation, thorough radiographic analysis and particularly the pathological examination to establish an accurate final diagnosis.

Imaging studies generally show the presence of a single or multillocular radiolucent area, with well-defined edges and regular margins. Larger lesions may become multillocular with scalloped borders. In many cases, an unerupted tooth is associated with the cystic lesion 8, which may raise doubts regarding the definitive diagnosis. Adjacent teeth may be displaced, but root resorption rarely occurs. CT scans and contrast-enhanced MRI may be useful in assessment of cortical perforation and soft tissue involvement 14.

It is possible to make the differential diagnosis with lesions such as the dentigerous cyst, ameloblastoma, calcifying odontogenic cyst, adenomatoid odontogenic tumor (AOT) and ameloblastic fibroma 15.

The gross findings of odontogenic keratocysts are a thin fibrous wall with approximately eight to ten layers of epithelial cells that is usually collapsed. When the cyst is received intact, however, the lumen may be filled with either clear fluid, yellow-white keratin, or an unerupted tooth 13. The classic histopathologic features of the odontogenic keratocyst are distinctive, but may be altered by inflammation. The uniformly thin epithelial lining of six to eight cells does not demonstrate rete ridges and may result in the epithelium lifting from the underlying fibrous connective tissue. This cleft is a microscopic feature that is considered artifactual but characteristic of the odontogenic keratocyst. The epithelium is also distinctive for a well-defined, pallisaded basal layer of hyperchromatic columnar to cuboidal cells. The luminal surface displays wavy parakeratotic epithelial cells and is frequently described as corrugated. Finally, the cystic cavity may contain keratinacious material 14.

Odontogenic keratocyst treatment

Different treatment modalities have been described and debated, ranging from conservative techniques to radical surgeries. Conservative methods described were simple enucleation, decompression or marsupialization and other techniques that are aggressive or non-conservative approaches such as cryosurgery or chemical destruction and radical surgery with bone resection 6. However, there is no consensus or adequate evidence for determining which is the most appropriate or appropriate technique for treating odontogenic keratocysts. Concerning the conservative approach, marsupialization and simple enucleation have shown high recurrence rates. For this reason, the combination of therapies has been selected in recent approaches reported in the literature, such as peripheral ostectomy performed with drill bits, cryotherapy and the use of chemical chelation by applying Carnoy’s Solution 16. The use of complementary techniques such as Carnoy’s solution and liquid nitrogen cryotherapy may cause unwanted side effects 6. On the other hand, techniques that are more radical are indicated in the treatment of lesions that involve adjacent soft tissues and in which there is evidence of cortical bone rupture. In these cases, the use of bone resection surgery with a free margin would be justified due to the high risk of recurrence and pathological fracture.

A recent systematic review and meta-analysis 17 based on the rates of OKC recurrence in patients submitted to conservative surgical treatments showed considerable results, which may vary significantly depending on the type of approach applied. Moreover, in a high percentage of cases reviewed in this study, almost 19.8 % developed a local recurrence of the initial pathological condition. On the other hand, lower recurrence rates were found in cases in which more aggressive treatments were applied, such as bone resection (0 %), 7.8 % for cases treated by enucleation and Carnoy’s solution, and 11.5 % for cases treated by enucleation and liquid nitrogen 17. Nevertheless, previous studies have pointed out the importance of a considerable length of follow-up of these lesions, because some cases showed no recurrence in a short-term follow-up, and this would be considered a weak point in most of the published articles 6.

In the contemporary literature, it was recommended and established that more aggressive treatment have many disadvantages when compared with the clinical results of the conservative approach 17, because the former produced significant morbidity such as facial deformities, loss of bone continuity (maxillary/mandible) reported in literature 18.

Carnoy’s solution, initially used as a slide fixator in laboratory pathology 19, is applied in the bone cavity for the purpose of eliminating the tumour tissue remnants by promoting a superficial chemical necrosis of up to 1.5 mm². In a previous study 20, which evaluated the clinical results observed with the use of Carnoy’s solution, suture dehiscence and postoperative infection occurred, in addition to nerve injuries causing temporary toxicity paresthesia due to the undesirable effect caused by Carnoy’s solution applied directly on the inferior alveolar nerve, determined by exposure of the nerve in these reported cases. Moreover, other studies argued about a time of critical exposure 21; however, studies that supported the use of Carnoy’s solution denied that it had a prolonged toxic effect on nerve tissues 22.

There are others effects mentioned in the contemporary literature 21 such as irreversible damage to the superficial and devitalized bony margin 23; but in a case report Vallejo-Rosero et al 3 used a Carnoy’s solution directly on the remnant alveolar ridge after lesion removal and no signs of toxicity were found in both the first a second surgery performed.

Moreover, enucleation alone followed by peripheral ostectomy and application of Carnoy’s solution was chosen in order to promote the complete removal of cell elements associated with odontogenic keratocyst, with the aim of minimizing the potential for recurrence and postoperative complications 21.

Thus, clinical aspects, tumor location and particularly the tomographic examination of the lesion justified the approach adopted, since there was no bone fenestration and lesion communication with the surrounding soft tissues. The integrity of the surgical space was observed and the surgical planning ruled out the necessity for adjacent soft tissue excision. Moreover, the macroscopic aspects of the lesion with integrity of the fibrous capsule during curettage reaffirmed the choice of peripheral ostectomy, as was performed in the initial surgical management 24.

Odontogenic keratocyst prognosis

Odontogenic keratocyst has a relatively high recurrence rate, around 7–28 % during the first 5 years after treatment. This variation occurs due to some of the diagnostic criteria and as a consequence of the treatment, taking into consideration appropriate use of the different techniques described above, location and extent of the lesion 25. Therefore, a long-term follow-up is recommended before and after the surgical treatment performed. Meanwhile, the prognosis is favorable.

References- K. M. Veena, Rekha Rao, H. Jagadishchandra, Prasanna Kumar Rao, “Odontogenic Keratocyst Looks Can Be Deceptive, Causing Endodontic Misdiagnosis”, Case Reports in Pathology, vol. 2011, Article ID 159501, 3 pages, 2011. https://doi.org/10.1155/2011/159501

- Chi A, Owings J, Muller S. Peripheral odontogenic keratocyst: report of two cases and review of the literature. Oral Surg Oral Med Oral Pathol Oral Radiol Endod. 2005;99:71–78. doi: 10.1016/j.tripleo.2004.05.018

- Vallejo-Rosero KA, Camolesi GV, de Sá PLD, Bernaola-Paredes WE. Conservative management of odontogenic keratocyst with long-term 5-year follow-up: Case report and literature review. Int J Surg Case Rep. 2020;66:8-15. doi:10.1016/j.ijscr.2019.11.023 https://www.ncbi.nlm.nih.gov/pmc/articles/PMC6889737

- Meara JG, Li KK, Shah SS, Cunningham MJ. Odontogenic keratocysts in the pediatric population. Arch Otolaryngol Head Neck Surg. 1996 Jul;122(7):725-8. doi: 10.1001/archotol.1996.01890190021006

- Grasmuck EA, Nelson BL. Keratocystic odontogenic tumor. Head Neck Pathol. 2010;4(1):94-96. doi:10.1007/s12105-009-0146-x https://www.ncbi.nlm.nih.gov/pmc/articles/PMC2825523

- Kaczmarzyk T, Mojsa I, Stypulkowska J. A systematic review of the recurrence rate for keratocystic odontogenic tumour in relation to treatment modalities. Int J Oral Maxillofac Surg. 2012 Jun;41(6):756-67. doi: 10.1016/j.ijom.2012.02.008

- Barnes L, Eveson JW, Reichart P, Sidransky D, editors. World health organization classification of tumours: pathology and genetics of head and neck tumours. Lyon: IARC Press; 2005.

- Payne TF. An analysis of the clinical and histopathologic parameters of the odontogenic keratocyst. Oral Surg Oral Med Oral Pathol. 1972 Apr;33(4):538-46. doi: 10.1016/0030-4220(72)90366-0

- Brannon RB. The odontogenic keratocyst. A clinicopathologic study of 312 cases. Part I. Clinical features. Oral Surg Oral Med Oral Pathol. 1976 Jul;42(1):54-72. doi: 10.1016/0030-4220(76)90031-1

- Godhi SS, Kukreja P. Keratocystic odontogenic tumor: A review. J Maxillofac Oral Surg 2009;8:127-31.

- K. M. Veena, Rekha Rao, H. Jagadishchandra, Prasanna Kumar Rao, “Odontogenic Keratocyst Looks Can Be Deceptive, Causing Endodontic Misdiagnosis”, Case Reports in Pathology, vol. 2011, Article ID 159501, 3 pages, 2011. https://doi.org/10.1155/2011/159501

- Jafaripozve S, Allameh M, Khorasgani MA, Jafaripozve N. Keratocyst odonogenic tumor in the anterior of the maxilla: A case report and literature review. J Oral Maxillofac Radiol 2013;1:90-2 https://www.joomr.org/text.asp?2013/1/2/90/120131

- Neville B.W., Damm D.D., Allen C.M., Bouquot J.E. 4th edition. Elsevier; 2016. Oral and Maxillofacial Pathology.

- Press S. Odontogenic tumors of the maxillary sinus. Curr Opin Otolaryngol Head Neck Surg. 2008;16:47–54. doi: 10.1097/MOO.0b013e3282f419da

- Bsoul SA, Paquette M, Terezhalmy GT, Moore WS. Odontogenic keratocyst. Quintessence Int. 2002 May;33(5):400-1.

- Fonseca E.V., Franzi S.A., Marcucci M., De Almeida R.C. Clinical, histopathological and treatment factor of the odontogenic keratocyst. Braz. J. Head Neck Surg. 2010;39(1):57–61.

- de Castro MS, Caixeta CA, de Carli ML, Ribeiro Júnior NV, Miyazawa M, Pereira AAC, Sperandio FF, Hanemann JAC. Conservative surgical treatments for nonsyndromic odontogenic keratocysts: a systematic review and meta-analysis. Clin Oral Investig. 2018 Jun;22(5):2089-2101. doi: 10.1007/s00784-017-2315-8

- Slusarenko da Silva Y, Stoelinga PJW, Naclério-Homem MDG. Recurrence of nonsyndromic odontogenic keratocyst after marsupialization and delayed enucleation vs. enucleation alone: a systematic review and meta-analysis. Oral Maxillofac Surg. 2019 Mar;23(1):1-11. doi: 10.1007/s10006-018-0737-3

- Pogrel M.A. The keratocystic odontogenic tumor. Oral Maxillofac. Surg. Clin. 2013;25(1):21–30.

- Ribeiro Júnior O. Oral and Maxillofacial Department, School of Dentistry, University of Sao Paulo; 2012. Study of Surgical Treatment of Keratocystic Odontogenic Tumors Associated or Not to the Nevoid Basal Cell Carcinoma Syndrome and Analysis of Recurrence-free Period. Doctoral Thesis.

- Belenguer A.D., Sánchez-Torres A., Gay-Escoda C. Role of carnoys solution in the treatment of keratocystic odontogenic tumor: a systematic review. Med. Oral Patol. Oral Cir. Bucal. 2016;21(6):e689–e695.

- Stoelinga PJ. Long-term follow-up on keratocysts treated according to a defined protocol. Int J Oral Maxillofac Surg. 2001 Feb;30(1):14-25. doi: 10.1054/ijom.2000.0027

- Morgan TA, Burton CC, Qian F. A retrospective review of treatment of the odontogenic keratocyst. J Oral Maxillofac Surg. 2005 May;63(5):635-9. doi: 10.1016/j.joms.2004.07.026

- Johnson NR, Batstone MD, Savage NW. Management and recurrence of keratocystic odontogenic tumor: a systematic review. Oral Surg Oral Med Oral Pathol Oral Radiol. 2013 Oct;116(4):e271-6. doi: 10.1016/j.oooo.2011.12.028

- Antonoglou G.N., Sándor G.K., Koidou V.P., Papageorgiou S.N. Non-syndromic and syndromic keratocystic odontogenic tumors: systematic review and meta-analysis of recurrences. J. Craniomaxillofac. Surg. 2014;42(7):e364–e371.