What is polyhydramnios

Polyhydramnios is when you have too much amniotic fluid in the amniotic sac for gestational age 1. The amniotic sac (or amnios) is the membranous sac surrounding the developing baby within the uterus (womb). The amniotic fluid within the sac is nourishing, and protects the baby while it is growing.

About 1 to 2 out of 100 (1-2 percent) pregnant women have polyhydramnios 1. It usually happens when amniotic fluid builds up slowly in the second half of pregnancy. In a small number of women, amniotic fluid builds up quickly. This can happen as early as 16 weeks of pregnancy and it usually causes very early birth.

Polyhydramnios isn’t usually a sign of anything serious, but you’ll probably have some extra check-ups and will be advised to give birth in hospital.

Many women with polyhydramnios don’t have symptoms. Polyhydramnios is often identified incidentally in the asymptomatic woman during sonographic evaluation for other conditions in the third trimester 1, 2. If you have a lot of extra amniotic fluid you may have belly pain and trouble breathing. This is because the uterus presses on your organs and lungs. Most cases of polyhydramnios are mild and result from a gradual buildup of amniotic fluid during the second half of pregnancy. Severe polyhydramnios may cause shortness of breath, preterm labor, or other signs and symptoms.

Your doctor uses ultrasound to measure the amount of amniotic fluid in the later stages of pregnancy. There are two ways to measure the amniotic fluid: amniotic fluid index (AFI) and maximum vertical pocket (MVP).

The amniotic fluid index (AFI) checks how deep the amniotic fluid is in four areas of your uterus. These amounts are then added up. If your amniotic fluid index (AFI) is more than 24 centimeters, you have polyhdramnios.

The maximum vertical pocket (MVP) measures the deepest area of your uterus to check the amniotic fluid level. If your maximum vertical pocket is more than 8 centimeters, you have polyhdramnios.

Polyhydramnios is generally defined as 3, 4, 5, 6:

- Amniotic fluid index (AFI) >25 cm

- Largest fluid pocket depth (maximal vertical pocket [MVP]) greater than 8 cm

- Some centers, particularly in Australia, New Zealand, and the United Kingdom, use a cut off of 10 cm

- Overall amniotic fluid volume larger than 1500-2000 mL

- Two diameter pocket (TDP) >50 cm 2

Ask your healthcare provider if you have questions about these measurements.

If you’re diagnosed with polyhydramnios, your health care provider will carefully monitor your pregnancy to help prevent complications. Treatment depends on the severity of the condition. Mild polyhydramnios may go away on its own. Severe polyhydramnios may require closer monitoring.

Will I have a healthy pregnancy and baby?

Most women with polyhydramnios won’t have any significant problems during their pregnancy and will have a healthy baby.

But there is a slightly increased risk of:

- Pregnancy and birth complications, such as giving birth prematurely (before 37 weeks), problems with the baby’s position, or a problem with the position of the umbilical cord (prolapsed umbilical cord)

- A problem with your baby

You’ll need extra check-ups to look for these problems, and you’ll normally be advised to give birth in hospital.

If you’ve been told you have polyhydramnios:

- try not to worry – remember polyhydramnios isn’t usually a sign of something serious

- get plenty of rest – if you work, you might consider starting your maternity leave early

- speak to your doctor about your birth plan – including what to do if your waters break or labor starts earlier than expected

- talk to your doctor if you have any concerns about yourself or your baby, get any new symptoms, feel very uncomfortable, or your tummy gets bigger suddenly

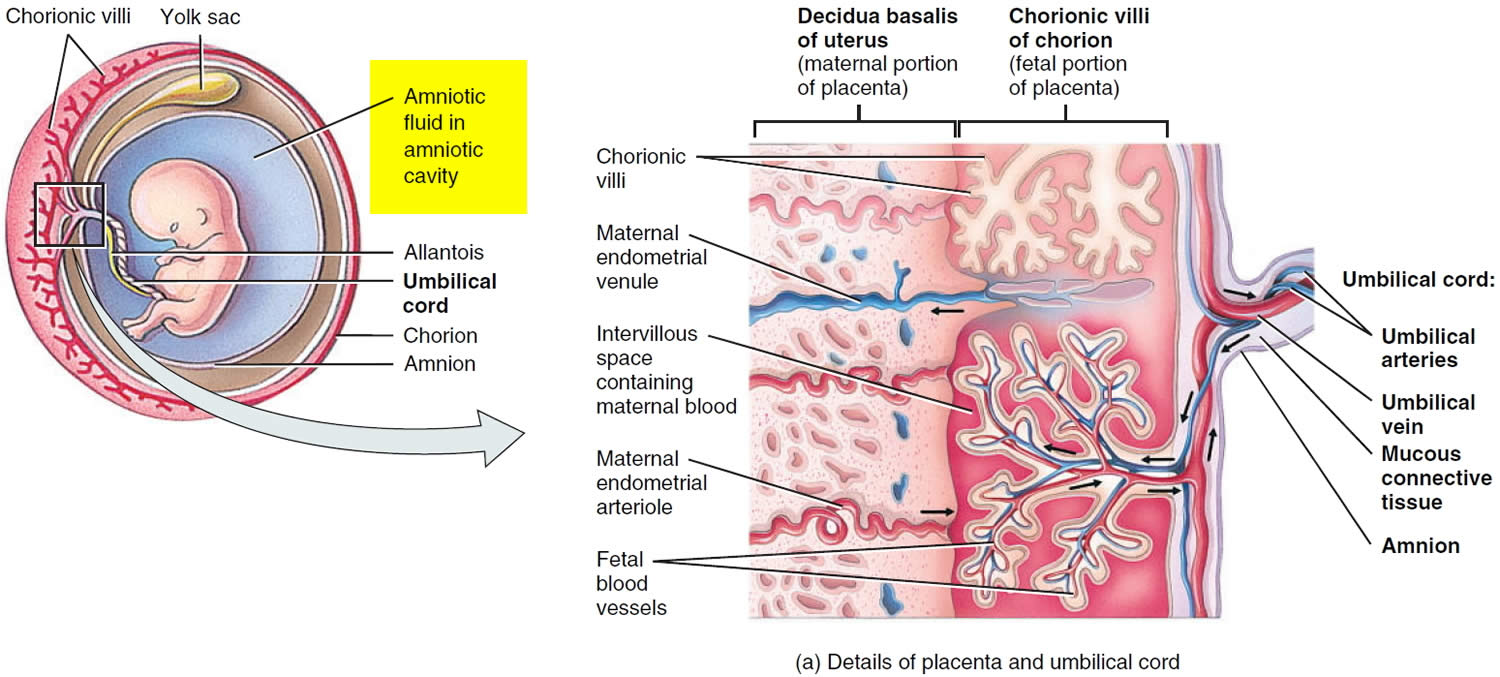

Amniotic fluid

Amniotic fluid is the fluid that surrounds your baby in your uterus (womb) (Figure 1). It’s very important for your baby’s development.

During pregnancy, your uterus is filled with amniotic fluid.

Here’s what the amniotic fluid does:

- Cushions and protects your baby

- Keeps a steady temperature around your baby

- Helps your baby’s lungs grow and develop because your baby breathes in the fluid

- Helps your baby’s digestive system develop because your baby swallows the fluid

- Helps your baby’s muscles and bones develop because your baby can move around in the fluid

- Keeps the umbilical cord (the cord that carries food and oxygen from the placenta to your baby) from being squeezed

The amniotic sac (bag) inside the uterus holds your growing baby. It is filled with amniotic fluid. This sac forms about 12 days after getting pregnant.

In the early weeks of pregnancy, the amniotic fluid is mostly water that comes from your body. After about 20 weeks of pregnancy, your baby’s urine makes up most of the fluid. Amniotic fluid also contains nutrients, hormones (chemicals made by the body) and antibodies (cells in the body that fight off infection).

Figure 1. Amniotic fluid and sac

What is amniotic fluid index?

Amniotic fluid index or AFI is an estimate of the amniotic fluid volume in a pregnant uterus on ultrasound. The normal range for amniotic fluid volumes varies with gestational age.

Typical amniotic fluid index (AFI) values include 7, 8, 9:

- Amniotic fluid index (AFI) between 5-25 cm is considered normal; median AFI level is approximately 14 cm from week 20 to week 35, after which the amniotic fluid volume begins to reduce

- Amniotic fluid index (AFI) <5 cm is considered to be oligohydramnios

- Value changes with age: the 5th percentile for gestational ages is most often taken as the cut-off value, and this is around an AFI of 7 cm for second and third-trimester pregnancies; an AFI of 5 cm is two standard deviations from the mean

- Amniotic fluid index (AFI) >25 cm is considered to be polyhydramnios

How much amniotic fluid should there be?

The amount of amniotic fluid increases until about 36 weeks of pregnancy. At that time, it makes up about 1 quart (946 ml). After that, the amount of amniotic fluid usually begins to decrease.

Sometimes you can have too little or too much amniotic fluid. Too little fluid is called oligohydramnios. Too much fluid is called polyhydramnios. Either one can cause problems for a pregnant woman and her baby. Even with these conditions, though, most babies are born healthy.

Does the color of amniotic fluid mean anything?

Normal amniotic fluid is clear or tinted yellow. Fluid that looks green or brown usually means that the baby has passed his first bowel movement (meconium) while in the womb. Usually, the baby has his first bowel movement after birth.

If the baby passes meconium in the womb, it can get into his lungs through the amniotic fluid. This can cause serious breathing problems, called meconium aspiration syndrome, especially if the fluid is thick.

Some babies with meconium in the amniotic fluid may need treatment right away after birth to prevent breathing problems. Babies who appear healthy at birth may not need treatment, even if the amniotic fluid has meconium.

What is maximal vertical pocket?

The maximal vertical pocket (MVP) also called the deepest vertical pocket depth is considered a reliable method for assessing amniotic fluid volume on ultrasound 10, 11. The maximal vertical pocket (MVP) depth is performed by assessing a pocket of a maximal depth of amniotic fluid which is free of an umbilical cord and fetal parts 12.

The usually accepted maximal vertical pocket (MVP) values are 12:

- <2 cm: indicative of oligohydramnios

- 2-8 cm: normal but should be taken in the context of subjective volume

- >8 cm: indicative of polyhydramnios (although some centers, particularly in Australia, New Zealand and the United Kingdom, use a cut off of >10 cm)

Polyhydramnios complications

The earlier that polyhydramnios occurs in pregnancy and the greater the amount of excess amniotic fluid, the higher the risk of complications.

Polyhydramnios may increase the risk of these problems during pregnancy 13, 14, 15:

- Premature birth (preterm birth) – Birth before 37 weeks of pregnancy

- Premature rupture of the membranes (PROM) – When the amniotic sac breaks after 37 weeks of pregnancy but before labor starts

- Placental abruption – When the placenta partially or completely peels away from the wall of the uterus before birth

- Umbilical cord prolapse — when the umbilical cord drops into the vagina ahead of the baby

- Stillbirth – When a baby dies in the womb after 20 weeks of pregnancy

- Postpartum hemorrhage – Severe bleeding after birth due to lack of uterine muscle tone after having a baby

- Fetal malposition – When a baby is not in a head-down position and may need to be born by Cesarean section (also called Cesarean birth or C-section)

- Cesarean section delivery

- Severe breathing problems during pregnancy

- Uterine atony – When the uterus becomes stretched out and can’t contract normally

- Macrosomia – When the baby weighs more than 8 pounds, 13 ounces (4,000 grams) at birth

- Shoulder dystocia – A birth injury that happens when one or both of a baby’s shoulders get stuck inside the pelvis during labor

- Birth defects, including problems with the baby’s bones and genetic conditions

If you have polyhydramnios, your doctor will monitor your condition closely during your pregnancy. They may perform a nonstress test. This test checks how your baby’s heart rate reacts when your baby moves.

Polyhydramnios causes

In about 60% to 70% of cases, doctors don’t know what causes polyhydramnios (idiopathic polyhydramnios) 1. In approximately 20% of cases, are due to a congenital anomaly 16.

Some known polyhydramnios causes are 1, 13, 15, 2, 16, 17:

- Birth defects, especially those that affect the baby’s swallowing or a blockage in the baby’s gut (gut atresia). A baby’s swallowing keeps the fluid in the womb at a steady level.

- Diabetes in the mother– Having too much sugar in your blood, including diabetes caused by pregnancy (gestational diabetes)

- Mismatch between your blood and your baby’s blood, such as Rh (Rhesus disease) and Kell diseases causing the baby’s blood cells being attacked by the mother’s blood cells

- A lack of red blood cells in the baby (fetal anemia)

- Twin-to-twin transfusion syndrome – If you’re carrying identical twins, this is when one twin gets too much blood flow and the other gets too little.

- Problems with the baby’s heart rate

- An infection in the baby (i.e., TORCH infections)

- A problem with the placenta

- a build-up of fluid in the baby (hydrops fetalis)

- A genetic problem in the baby

Most babies whose mothers have idiopathic polyhydramnios will be healthy. However, an underlying disease or congenital anomaly has been identified in 91% of cases with more severe polyhydramnios. These patients are more likely to be symptomatic due to significant amniotic fluid volume 2, 1, 15. Speak to your doctor or midwife if you’re concerned or have any questions.

Polyhydramnios symptoms

Polyhydramnios tends to develop gradually and many women with polyhydramnios don’t have symptoms.

Polyhydramnios symptoms result from pressure being exerted within the uterus and on nearby organs.

Mild polyhydramnios may cause few — if any — signs or symptoms. If you have a lot of extra amniotic fluid you may have belly pain and trouble breathing. This is because the uterus presses on your organs and lungs.

Severe polyhydramnios may cause:

- Breathlessness or shortness of breath or the inability to breathe

- Feeling tightness in your stomach

- Swelling in the lower extremities – swelling in your leg, thigh, hip, ankle or foot

- Upset stomach or heartburn

- Constipation (trouble moving bowels)

- Feeling your bump is very big and heavy

- Peeing less frequently

- Uterine discomfort or contractions

- Having an enlarged vulva (the outer part of the vagina)

But these are common problems for pregnant women and aren’t necessarily caused by polyhydramnios. See your doctor if you have these symptoms and you’re worried.

Your health care provider may also suspect polyhydramnios if your uterus is excessively enlarged and he or she has trouble feeling the baby.

In rare cases, fluid can build up around the baby quickly. See your doctor if your tummy gets bigger suddenly.

Polyhydramnios diagnosis

If your doctor suspects polyhydramnios, he or she will do a fetal ultrasound. This test uses high-frequency sound waves to produce images of your baby on a monitor.

If the initial ultrasound shows evidence of polyhydramnios, your health care provider may do a more detailed ultrasound. He or she will estimate the amniotic fluid volume by measuring the single largest, deepest pocket of fluid around your baby called the maximal vertical pocket (MVP). If your maximal vertical pocket (MVP) is more than 8 centimeters, you have polyhydramnios.

An alternative way of measuring amniotic fluid is measuring the largest pocket in four specific parts of your uterus. The sum of these measurements is the amniotic fluid index (AFI). An AFI of 25 centimeters or more indicates polyhydramnios. Your doctor will also use a detailed ultrasound to diagnose or rule out birth defects and other complications.

Ask your doctor if you have questions about these measurements.

Your doctor may offer additional testing if you have a diagnosis of polyhydramnios. Testing will be based on your risk factors, exposure to infections and prior evaluations of your baby.

Additional tests may include:

- Blood tests. Blood tests for infectious diseases associated with polyhydramnios may be offered.

- Amniocentesis. Amniocentesis is a procedure in which a sample of amniotic fluid — which contains fetal cells and various chemicals produced by the baby — is removed from the uterus for testing. Testing may include a karyotype analysis, used to screen the baby’s chromosomes for abnormalities.

If you’re diagnosed with polyhydramnios, your health care provider will closely monitor your pregnancy. Monitoring may include the following:

- Nonstress test. This test checks how your baby’s heart rate reacts when your baby moves. During the test, you’ll wear a special device on your abdomen to measure the baby’s heart rate. You may be asked to eat or drink something to make the baby active. A buzzer-like device also may be used to wake the baby and encourage movement.

- Biophysical profile. This test uses an ultrasound to provide more information about your baby’s breathing, tone and movement, as well as the volume of amniotic fluid in your uterus. It may be combined with a nonstress test.

Polyhydramnios treatment

When an ultrasound shows you have too much amniotic fluid, your doctor does a more detailed ultrasound to check for birth defects and twin-to-twin transfusion syndrome.

Your doctor also may recommend a blood test for diabetes and an amniocentesis. Amniocentesis is a test that takes some amniotic fluid from around the baby to check for problems, like birth defects.

In many cases, mild polyhydramnios goes away by itself. Other times, it may go away when the problem causing it is fixed. For example, if your baby’s heart rate is causing the problem, sometimes your doctor can give you medicine to fix it.

In other cases, treatment for an underlying condition — such as diabetes — may help resolve polyhydramnios.

If you have mild to moderate polyhydramnios, you’ll likely be able to carry your baby to term, delivering at 39 or 40 weeks. If you have severe polyhydramnios, your health care provider will discuss the appropriate timing of delivery, to avoid complications for you and your baby.

If you have polyhydramnios, you usually have ultrasounds weekly or more often to check amniotic fluid levels. You may also have tests to check your baby’s health.

Having too much amniotic fluid may make you uncomfortable. Your doctor may give you medicine called indomethacin. This medicine helps lower the amount of urine that your baby makes, so it lowers the amount of amniotic fluid. Indomethacin isn’t recommended beyond 31 weeks of pregnancy. Due to the risk of fetal heart problems, your baby’s heart may need to be monitored with a fetal echocardiogram and Doppler ultrasound. Other side effects may include nausea, vomiting, acid reflux and inflammation of the lining of the stomach (gastritis).

Amniocentesis also can remove extra fluid. Your health care provider may use amniocentesis to drain excess amniotic fluid from your uterus. This procedure carries a small risk of complications, including preterm labor, placental abruption and premature rupture of the membranes.

After treatment, your doctor will still want to monitor your amniotic fluid level approximately every one to three weeks.

If you have slight polyhdramnios near the end of your pregnancy but tests show that you and your baby are healthy, you usually don’t need any treatment.

During the rest of your pregnancy, you’ll probably have:

- extra antenatal appointments and ultrasound scans to check for problems with you and your baby

- tests to look for causes of polyhydramnios, such as a blood test for diabetes in pregnancy or amniocentesis (where some amniotic fluid is removed and tested)

- treatment for the underlying cause, if one is found – for example, changes to your diet or possibly medication if you have diabetes

Your doctor may also talk to you about any changes to your birth plan.

You’ll normally be advised to give birth in hospital. This is so any equipment or treatment needed for you or your baby is easily available.

You can usually wait for labor to start naturally. Sometimes induction (starting labor with medication) or a caesarean section (an operation to deliver your baby) may be needed if there’s a risk to you or your baby.

You’ll probably pass a lot of fluid when you give birth – this is normal and nothing to worry about. Your baby’s heartbeat may also need to be monitored during labor.

After giving birth, your baby will have an examination to check they’re healthy and they may have some tests – for example, a tube may be passed down their throat to check for a problem with their gut.

Polyhydramnios prognosis

The prognosis for mild idiopathic polyhydramnios is excellent 16. Maternal and fetal prognosis decreases with the severity of polyhydramnios. The majority of cases of idiopathic polyhydramnios are self-limited and will usually resolve without any intervention.

The risk of complications increases with the overdistension of the uterus (the severity of polyhydramnios). These include maternal shortness of breath (dyspnea), preterm labor, premature rupture of membranes (PROM), breech presentation, umbilical cord prolapse, postpartum hemorrhage, fetal macrosomia associated with maternal diabetes, hypertensive disorders, and urinary tract infections.

Data on the intrauterine fetal demise in polyhydramnios is inconsistent. Severe and rapidly progressing polyhydramnios is an independent risk factor for perinatal mortality. In addition, small for gestational age fetuses with polyhydramnios have the poorest prognosis. The prognosis directly correlates with the underlying cause of polyhydramnios.

References- Hamza A, Herr D, Solomayer EF, Meyberg-Solomayer G. Polyhydramnios: Causes, Diagnosis and Therapy. Geburtshilfe Frauenheilkd. 2013 Dec;73(12):1241-1246. doi: 10.1055/s-0033-1360163

- Society for Maternal-Fetal Medicine (SMFM). Dashe JS, Pressman EK, Hibbard JU. SMFM Consult Series #46: Evaluation and management of polyhydramnios. Am J Obstet Gynecol. 2018 Oct;219(4):B2-B8. doi: 10.1016/j.ajog.2018.07.016

- Refaey M, Jones J, Rasuli B, et al. Polyhydramnios. Reference article, Radiopaedia.org https://doi.org/10.53347/rID-4797

- Magann EF, Chauhan SP, Doherty DA, Lutgendorf MA, Magann MI, Morrison JC. A review of idiopathic hydramnios and pregnancy outcomes. Obstet Gynecol Surv. 2007 Dec;62(12):795-802. doi: 10.1097/01.ogx.0000290349.58707.e0

- Sohaey R, Nyberg DA, Sickler GK, Williams MA. Idiopathic polyhydramnios: association with fetal macrosomia. Radiology. 1994 Feb;190(2):393-6. doi: 10.1148/radiology.190.2.8284386

- Hashimoto B, Callen P, Filly R, Laros R. Ultrasound Evaluation of Polyhydr Amnios and Twin Pregnancy. American Journal of Obstetrics and Gynecology. 1986;154(5):1069-72. https://doi.org/10.5555/uri:pii:0002937886907520

- Magann EF, Sanderson M, Martin JN, Chauhan S. The amniotic fluid index, single deepest pocket, and two-diameter pocket in normal human pregnancy. Am J Obstet Gynecol. 2000 Jun;182(6):1581-8. doi: 10.1067/mob.2000.107325

- Hallak M, Kirshon B, Smith EO, Cotton DB. Amniotic fluid index. Gestational age-specific values for normal human pregnancy. J Reprod Med. 1993 Nov;38(11):853-6.

- Porter TF, Dildy GA, Blanchard JR, Kochenour NK, Clark SL. Normal values for amniotic fluid index during uncomplicated twin pregnancy. Obstet Gynecol. 1996 May;87(5 Pt 1):699-702. doi: 10.1016/0029-7844(96)00006-3

- Magann EF, Chauhan SP, Doherty DA, Magann MI, Morrison JC. The evidence for abandoning the amniotic fluid index in favor of the single deepest pocket. Am J Perinatol. 2007 Oct;24(9):549-55. doi: 10.1055/s-2007-986689

- Magann, E.F., Chauhan, S.P., Washington, W., Whitworth, N.S., Martin, J.N., JR and Morrison, J.C. (2002), Ultrasound estimation of amniotic fluid volume using the largest vertical pocket containing umbilical cord: measure to or through the cord?. Ultrasound Obstet Gynecol, 20: 464-467. https://doi.org/10.1046/j.1469-0705.2002.00802.x

- Radswiki T, Haouimi A, Jones J, et al. Deepest vertical pocket method. Reference article, Radiopaedia.org https://doi.org/10.53347/rID-14752

- Luo QQ, Zou L, Gao H, Zheng YF, Zhao Y, Zhang WY. Idiopathic polyhydramnios at term and pregnancy outcomes: a multicenter observational study. J Matern Fetal Neonatal Med. 2017 Jul;30(14):1755-1759. doi: 10.1080/14767058.2016.1224835

- Kollmann M, Voetsch J, Koidl C, Schest E, Haeusler M, Lang U, Klaritsch P. Etiology and perinatal outcome of polyhydramnios. Ultraschall Med. 2014 Aug;35(4):350-6. doi: 10.1055/s-0034-1366115

- Cardwell MS. Polyhydramnios: a review. Obstet Gynecol Surv. 1987 Oct;42(10):612-7. doi: 10.1097/00006254-198710000-00001

- Hwang DS, Mahdy H. Polyhydramnios. [Updated 2022 Sep 6]. In: StatPearls [Internet]. Treasure Island (FL): StatPearls Publishing; 2022 Jan-. Available from: https://www.ncbi.nlm.nih.gov/books/NBK562140

- Society for Maternal-Fetal Medicine; Simpson LL. Twin-twin transfusion syndrome. Am J Obstet Gynecol. 2013 Jan;208(1):3-18. doi: 10.1016/j.ajog.2012.10.880. Erratum in: Am J Obstet Gynecol. 2013 May;208(5):392.