Shoulder dystocia

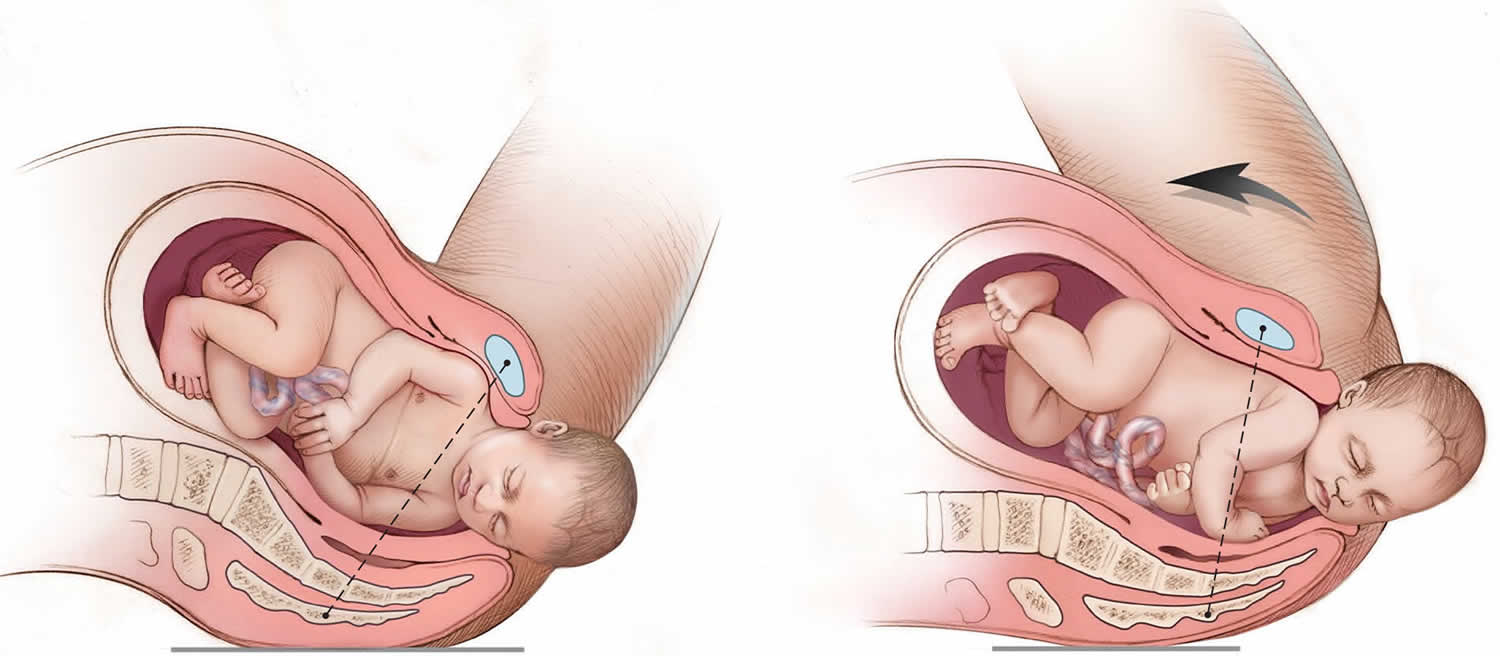

Shoulder dystocia is a medical emergency that happens when one or both of the baby’s shoulders gets stuck behind the mother’s pubic bone (the bone behind the pubic hair) or sacrum (the bone at the back of the pelvis, above the tailbone) during vaginal birth 1, 2, 3. Shoulder dystocia is usually attributed to impaction of the anterior shoulder against the maternal symphysis after delivery of the fetal head; less commonly, it is caused by impaction of the posterior shoulder against the sacral promontory 4. The word dystocia comes from the Greek words “dys,” meaning difficult, and “tokos,” meaning birth. During the second stage of labor, there is normally a pause after the baby’s head has been born but before the body comes out. When shoulder dystocia occurs, this delay is longer delay than normal. The baby will need emergency help to be born. Attempts at delivery can result in fractures of the baby’s collarbone or arm and damage to the nerves in the shoulders, arms, and hands. In severe cases, lack of oxygen during the birth process can lead to brain damage or death. Shoulder dystocia also can cause maternal complications, such as vaginal and perineal tears and bleeding. Unfortunately, there is no established method to reliably predict shoulder dystocia, which occurs in about 0.3% to 3% of all vaginal deliveries 5, 6. Shoulder dystocia is more common during a vaginal birth, but a baby’s shoulder can also get stuck during a cesarean section.

Shoulder dystocia occurs in 0.6% to 1.4% of babies weighing between 5 pounds, 8 ounces and 8 pounds, 13 ounces at birth. The rate increases to 5% to 9% of babies born weighing more than 8 pounds, 13 ounces also known as ‘fetal macrosomia’. However, most cases of shoulder dystocia occur out of the blue with no predictive factors and normal-sized babies.

Shoulder dystocia is a medical emergency. While the baby is stuck, they cannot breathe and the umbilical cord may be squeezed. They will need help to be born quickly so they can get enough oxygen. It can also cause a fracture of the baby’s collarbone or upper arm, nerve damage affecting the shoulders, arms, hands or fingers, brain damage or speech disability. Sadly, there is a risk that lack of oxygen during birth can lead to brain damage or even death.

Sometimes shoulder dystocia can lead to complications for the mother, including tears, a hemorrhage, infection, or damage to the nerves causing incontinence.

These complications are very rare, and doctors and midwives are highly trained to deal with shoulder dystocia if it happens.

Figure 1. Shoulder dystocia

Causes of shoulder dystocia

Shoulder dystocia can happen during any vaginal birth. Shoulder dystocia occurs when your baby’s shoulder or shoulders get stuck behind your pubic bones during vaginal delivery. It is usually because the baby is too big, because it is in the wrong position, or because the mother is in a position that restricts the room in the pelvis.

It is impossible to predict whether shoulder dystocia will happen, but there are some things that make it more likely, including when you:

- experienced shoulder dystocia during a previous labor

- are having a large baby where your baby weighs more than 8 pounds, 13 ounces (called ‘fetal macrosomia’)

- are having twins or multiple babies

- are very overweight

- have diabetes

- are in a position that limits the room in your pelvis

- your pelvic opening is too small

- have had labor induced, or other interventions are used during labor

Shoulder dystocia can also happen if the labor goes very quickly or very slowly.

Risk factors for predicting shoulder dystocia

Shoulder dystocia can happen to anyone. Most cases of shoulder dysplasia occur in babies with normal birth weights. But certain risk factors increase the likelihood of shoulder dysplasia. Risk factors for predicting shoulder dystocia can be divided into a) antepartum (the period during which a woman is pregnant and before childbirth) and b) intrapartum (time period spanning childbirth, from the onset of labor through delivery of the placenta) 7, 8, 9, 10. However, most cases of shoulder dystocia occur out of the blue with no predictive factors and normal-sized babies 11, 12.

- Antepartum risk factors include:

- shoulder dystocia in a previous pregnancy,

- clinical or ultrasound suspected large baby or macrosomia. Macrosomia means your baby weighs more than 8 pounds, 13 ounces at birth. If you have a big baby, your healthcare provider may recommend a C-section.

- maternal diabetes. Pre-existing diabetes and gestational diabetes can both cause your baby to be large. People with diabetes have a 20% chance of delivering a baby weighing more than 8 pounds, 13 ounces at birth.

- pregnant with twins or other multiples,

- overweight and/or gaining excess weight during pregnancy with maternal body mass index (BMI) > 35

- short stature

- abnormal pelvic structure such as having a small pelvis or your pelvic opening is too small,

- older than 35,

- giving birth after your due date,

- induction of labor.

- Intrapartum (during labor and delivery) risk factors include:

- very long first stage of labor (contraction phase),

- using inappropriate pressure or maneuvers to deliver your baby,

- very short or very long second stage of labor (pushing phase),

- your baby is in the wrong position,

- you are in a position that limits the room in your pelvis,

- getting an epidural,

- taking oxytocin (Pitocin) to induce labor,

- assisted vaginal delivery. This means your obstetrician has to use a vacuum extractor or forceps to help deliver your baby through the birth canal.

Given the increased risk of shoulder dystocia with increasing fetal weights, the American College of Obstetricians and Gynecologists (ACOG) recommends consideration of cesarean delivery for a patient who does not have diabetes and is carrying a fetus with an estimated fetal weight of 5,000 g (11 lb) 11. The American College of Obstetricians and Gynecologists also recommends consideration of cesarean delivery for a patient who has diabetes and is carrying a fetus with an estimated fetal weight of 4,500 g (9 lb, 15 oz) 11.

Shoulder dystocia prevention

Shoulder dystocia is unpredictable and can happen to anyone, so there is very little you can do to prevent it. Most shoulder dystocia cases happen in babies with normal birth weights and can’t be prevented. Managing conditions like your diabetes and watching your weight during pregnancy can help. If your baby is big, it may be a good idea to give birth lying on your side or on all fours.

You can lower your risk of shoulder dystocia by:

- Managing your diabetes.

- Maintaining a healthy weight throughout your pregnancy.

- Asking your obstetrician about inducing labor.

- If you’re past your due date, see your healthcare provider.

- Discussing the possibility of a C-section with your obstetrician.

- Consider forgoing labor medications such as an epidural.

The American College of Obstetricians and Gynecologists and the Advanced Life Support in Obstetrics program recommend that labor and delivery teams conduct regular team training drills that include identification and management of shoulder dystocia 11, 13.

Cesarean section should be recommended in order to prevent shoulder dystocia only in the following cases 14:

- Fetus with weight >4.5 kg, if associated with maternal diabetes;

- Fetus with weight >5 kg and with an absence of maternal diabetes;

- Previous history of shoulder dystocia with severe maternal and neonatal complications; and

- Fetal macrosomia with a failure in progress to the second stage of delivery.

The main point is knowledge of the weight of the fetus, to avoid a difficult delivery including shoulder dystocia. This could be assessed by ultrasound which can estimate approximatively the weight of the fetus, but in some cases it can be over- or under-estimated. In case of very probable macrosomia, a cesarean section should be performed in order to avoid the difficult delivery of shoulder dystocia.

Shoulder dystocia signs and symptoms

While there are risk factors that can lead to shoulder dystocia, most cases of shoulder dystocia occur out of the blue with no predictive factors and normal-sized babies. There are no symptoms, and there’s no way to predict if shoulder dystocia will occur. Your obstetrician may only notice the condition after you deliver your baby’s head. It becomes clear when your baby’s head emerges and then pulls back in against the area between your vagina and rectum (perineum). This is called the “turtle sign.”

Shoulder dystocia complications

Complications resulting from shoulder dystocia during labor can affect you and your baby 11.

Complications that can affect you:

- Extreme heavy bleeding after giving birth (postpartum hemorrhage).

- Severe tearing of the area between your vagina and anus (perineal tear).

- Rectovaginal fistula: A rectovaginal fistula is an abnormal connection between your vagina and rectum.

- Uterine rupture: A uterine rupture means your uterus tears during labor.

- Separation of your pubic bones.

Complications that can affect your baby

The most common complication of shoulder dystocia in your baby is brachial plexus palsy. The brachial plexus nerves run from your baby’s spinal cord in their neck through their arm. These nerves are responsible for providing feeling and movement in your baby’s shoulder, arm and hand. Damage to these nerves can cause weakness and paralysis on the affected side. Other complications to your baby may include:

- Fractures to your baby’s collarbone (clavicle) and/or upper arm bone (humerus).

- Horner’s syndrome: A rare disorder affecting your baby’s eyes and face.

- Compressed umbilical cord: The umbilical cord can get trapped between your baby’s arm and your pelvic bone. When the umbilical cord is flattened, it can cut off oxygen and blood flow to your baby. This is very rare, but it can cause brain injury or death.

The most common maternal complications are postpartum hemorrhage (11%) and obstetric anal sphincter injuries (3.8%) 15. The most common neonatal injuries are brachial plexus injuries and clavicular or humeral fractures 16. Transient brachial plexus injuries may occur in up to 20% of deliveries complicated by shoulder dystocia 5. Most resolve without permanent disability, although approximately 10% may result in permanent neurologic injury 17. The head-to-body delivery interval does not predict fetal asphyxia or death 11. However, due to the potential for serious maternal or neonatal harm, a systematic approach to expeditious delivery is necessary 11.

Shoulder dystocia diagnosis

Shoulder dystocia is, by definition, a mechanical problem occurring during a vaginal delivery. Your obstetrician will diagnose shoulder dystocia if three factors are met:

- You delivered your baby’s head but you aren’t able to push your baby’s shoulders out.

- At least one minute has passed since your baby’s head has emerged but their body hasn’t.

- Your baby needs delivery maneuvers to be delivered successfully.

Shoulder dystocia management

Shoulder dystocia is an obstetric emergency when one or both of the baby’s shoulders gets stuck behind the mother’s pubic bone (the bone behind the pubic hair) or sacrum (the bone at the back of the pelvis, above the tailbone) during vaginal birth. Normal traction on the baby’s head does not lead to delivery of the shoulders. This can cause neonatal brachial plexus injuries, hypoxia, and maternal trauma, including damage to the bladder, anal sphincter, and rectum, and postpartum hemorrhage. If your doctor or midwife suspects shoulder dystocia, they will first tell you to stop pushing. They will immediately call for help, since you may need other specialist doctors to care for you or the baby.

The HELPERR mnemonic is a tool your healthcare team may use to treat shoulder dystocia 18. HELPERR stands for 19:

- H — Help: Your obstetrician will call for help. They’ll use the safety checklist and call for additional help from other healthcare providers. These providers may include an anesthesiologist, a neonatologist and extra labor and delivery Necessary equipment will be brought to your room.

- E — Evaluate for episiotomy: Your obstetrician will decide if you need an episiotomy to assist with the delivery of your baby. An episiotomy is a cut (incision) in your perineum to make the opening to your vagina larger. Your obstetrician will only perform episiotomy if they need to make room for rotation maneuvers.

- L — Legs: Your obstetrician may use the McRoberts maneuver. With the McRoberts maneuver, your obstetrician will ask you to lie flat on your back with your knees pulled back as far as they can go up against your belly (abdomen). This method helps to flatten and rotate your pelvis. The midwife or doctor will gently press on your abdomen to help free the baby’s shoulder.

- P — Pressure: Your obstetrician may use suprapubic pressure. With suprapubic pressure, your obstetrician will press on your lower belly (abdomen) above your pubic bone. This puts pressure on your baby’s shoulder in an attempt to rotate and deliver it.

- E — Enter rotational maneuvers: Your obstetrician may perform enter maneuvers or internal rotation maneuvers. Your obstetrician will reach up into your vagina to try to turn your baby. Sometimes, simply changing your position can free the baby’s shoulder. You might be asked to lie flat on your back with your knees pulled back as far as they can go.

- R — Remove posterior arm: Your obstetrician may use Jacquemier’s maneuver. With Jacquemier’s maneuver, your obstetrician will remove one of your baby’s arms from the birth canal. This may make it easier for their shoulders to pass through.

- R — Roll the patient: Your obstetrician may use the Gaskin maneuver. With the Gaskin maneuver, your obstetrician will have you turn over on your hands and knees to get into a new position.

In severe cases when other techniques aren’t working, your obstetrician may use one of the following last resort methods 19:

- Clavicle fracture: In very rare cases, your obstetrician will break your baby’s collarbone to release their shoulders and get them out. Baby’s collarbone will heal quickly afterwards.

- Zavanelli maneuver: Your obstetrician will push your baby’s head back into your uterus and perform a cesarean section (C-section) under general anesthetic. Once the anesthetic has taken effect, the baby will be pushed back into your uterus and delivered through your abdomen.

- Symphysiotomy: Your obstetrician will make a cut (incision) in the cartilage between your pubic bones to enlarge your pelvic opening.

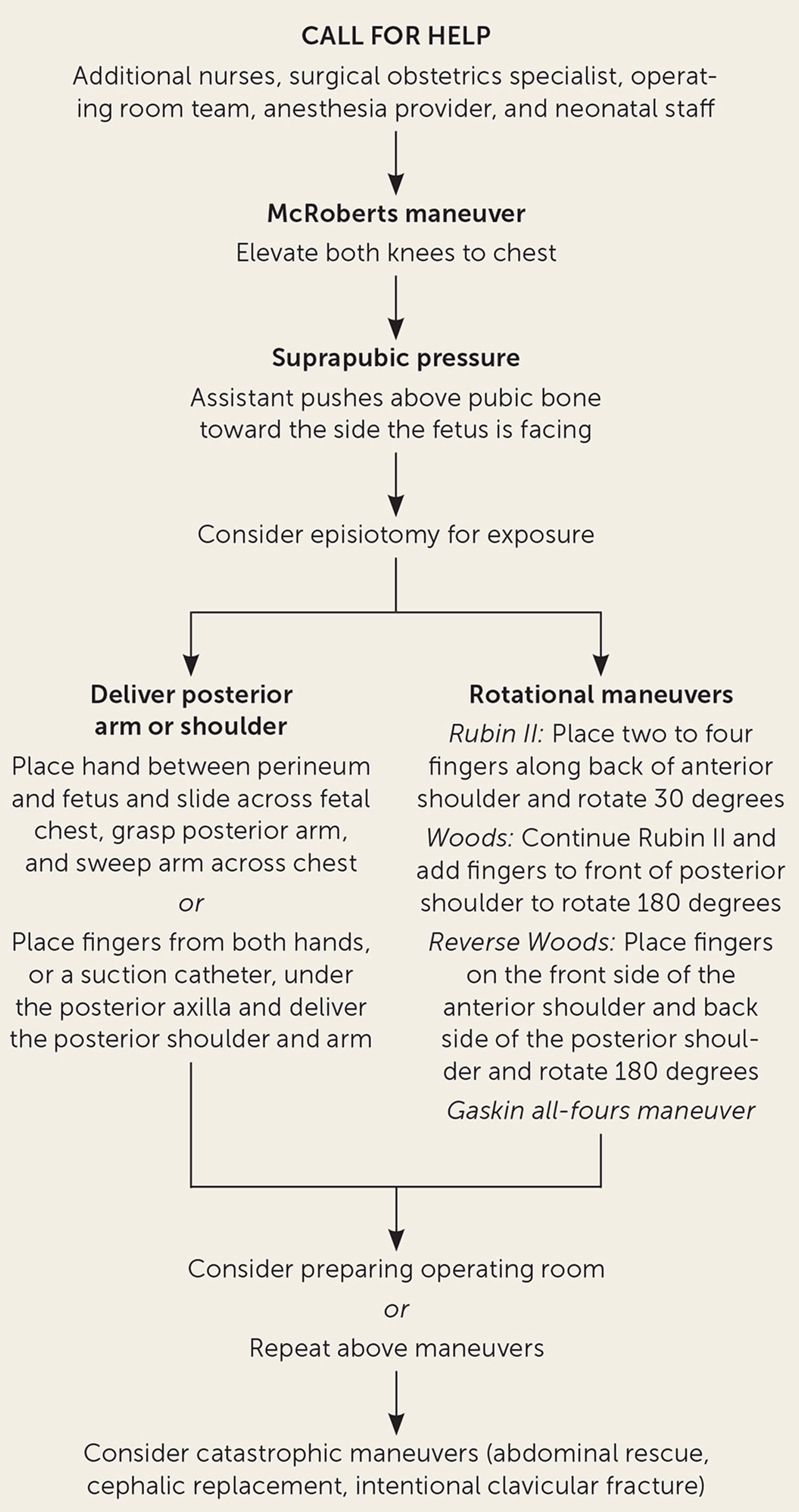

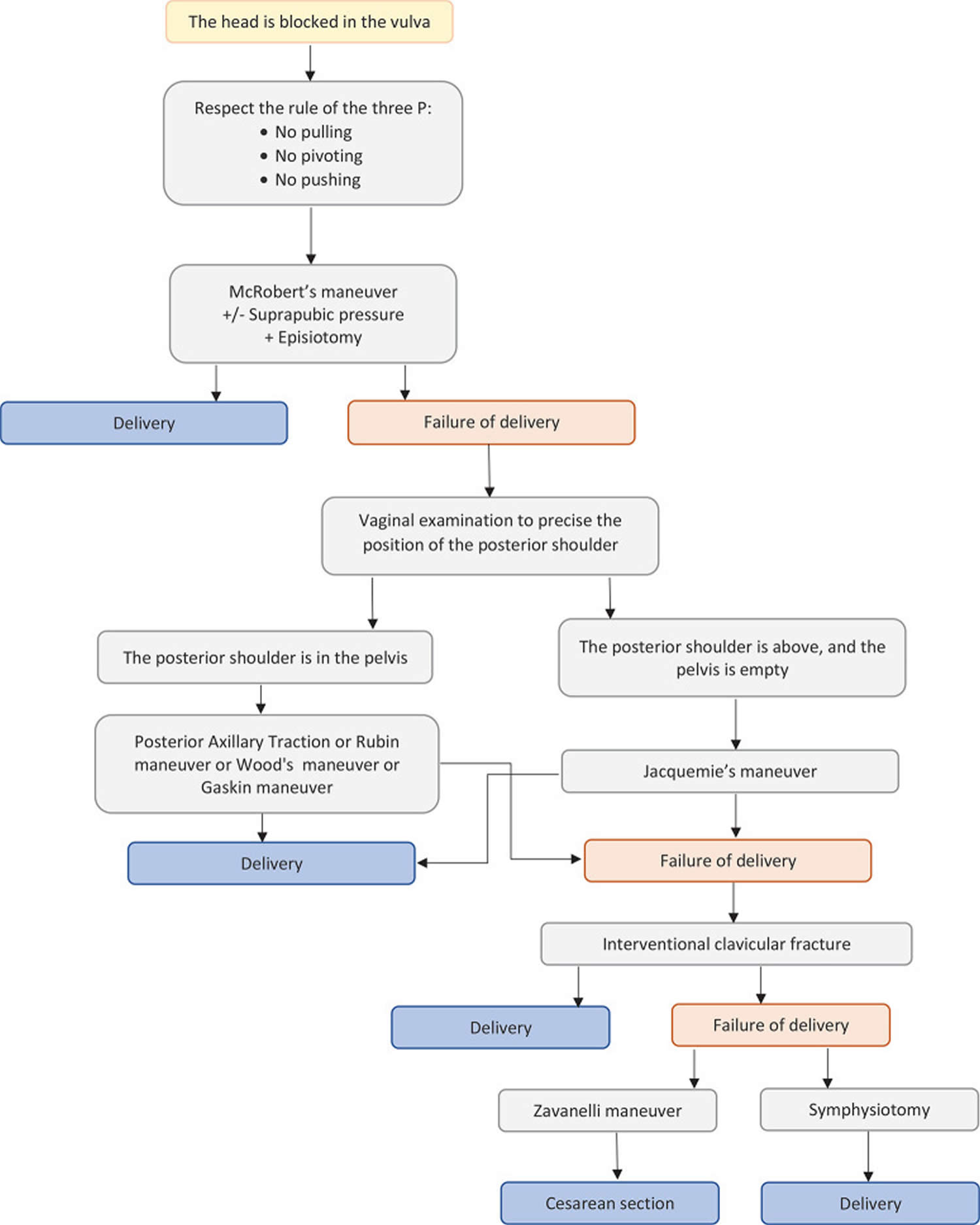

Figure 2. Shoulder dystocia management algorithm

[Source 1 ] [Source 20 ]Shoulder dystocia maneuvers

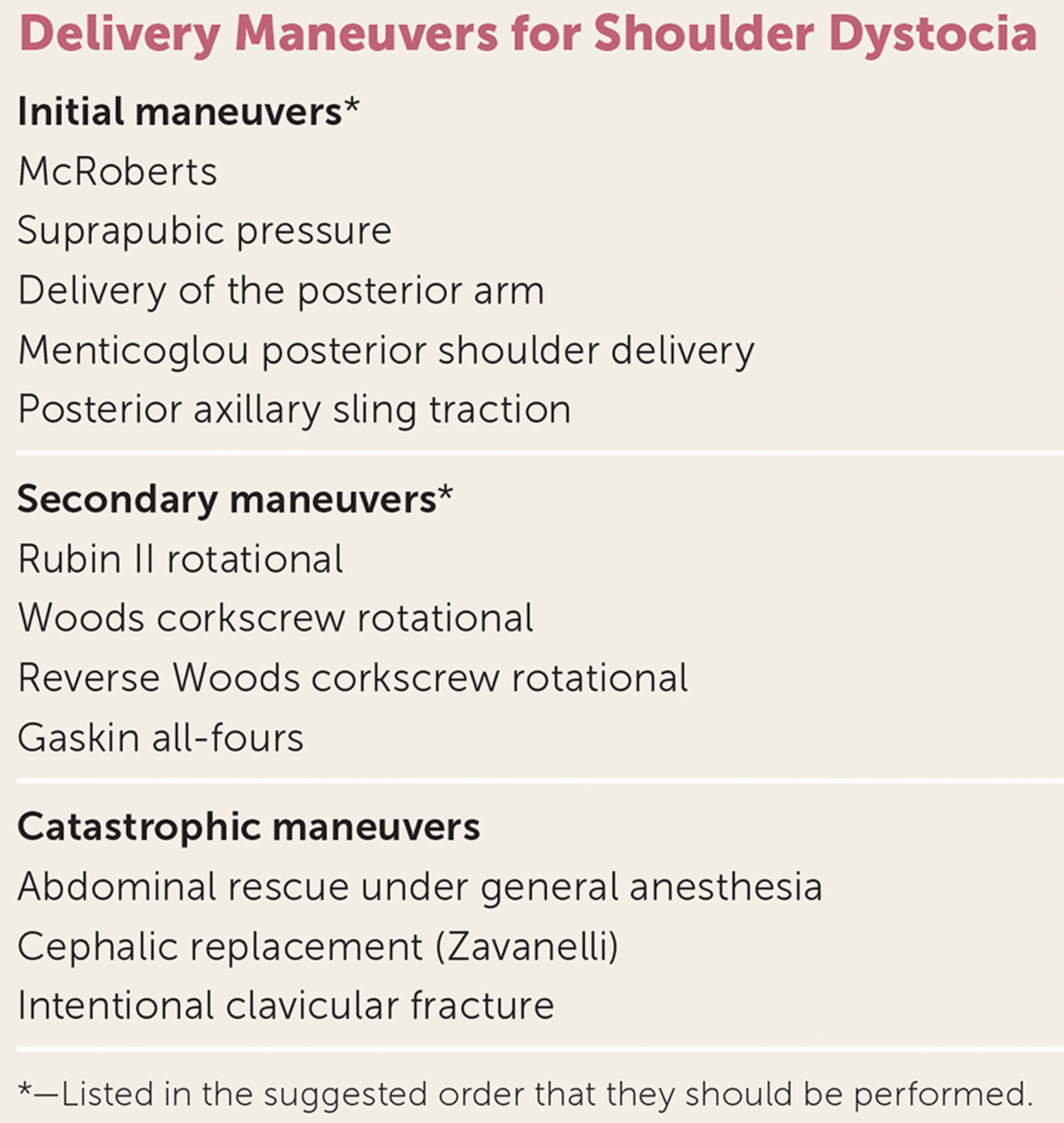

If the baby does not deliver using gentle traction, release maneuvers can be used in a thoughtful and sequential manner to deliver the impacted shoulder (Figure 2). Aggressive lateral or downward traction on the fetal head and neck should be avoided because it can injure the brachial plexus 5. There are no randomized trials comparing the various maneuvers used to release an impacted shoulder 11. The American College of Obstetricians and Gynecologists, the Royal College of Obstetricians and Gynaecologists, and the Advanced Life Support in Obstetrics program recommend using the McRoberts maneuver first, followed by suprapubic pressure if necessary 11, 13, 21. The McRoberts maneuver, performed by flexing the hips and bringing both knees toward the chest, rotates the symphysis pubis cephalad and further opens the pelvic outlet. This is a simple and proven method to manage shoulder dystocia, with a success rate of up to 42% as the sole maneuver 11, 15.

Figure 3. Shoulder dystocia maneuvers

[Source 1 ]McRoberts maneuver

McRoberts maneuver is performed by flexing the patient’s hips and bringing both her knees toward her chest, which causes cephalad rotation of the maternal symphysis pubis and flattening of the sacrum, further opening the pelvic outlet (Figure 4).

If delivery does not occur, firm, steady suprapubic pressure (also known as Mazzanti maneuver) should be performed concurrently with the McRoberts maneuver (Figure 5). An assistant should apply firm downward or oblique pressure just above the symphysis pubis toward the side the infant is facing. This decreases the distance between the infant’s shoulders (bisacromial distance), potentially assisting anterior shoulder dislodgement. Apply a steady pressure first and, if unsuccessful, apply a rocking pressure. Do NOT use fundal pressure. Fundal pressure increases the risk of uterine rupture 22. Suprapubic pressure (Mazzanti maneuver) in combination with the McRoberts maneuver will deliver the baby in 91% of cases 23.

If the McRoberts maneuver and suprapubic pressure (Mazzanti maneuver) are unsuccessful, delivery of the posterior arm (Jacquemier’s maneuver) should be considered (Figure 6) 11, 13, 24. In the posterior arm release or Jacquemier’s maneuver, the physician’s hand enters the pelvis posteriorly and travels along the fetal chest to grasp the fetal posterior wrist using an OK sign 25. The operator’s hand should slide along the fetal chest, not the back, which may involve using the physician’s nondominant hand depending on the direction the fetus is facing. Hooking the little finger around the fetal elbow may facilitate the maneuver. The arm is then swept across the fetal chest. Then, with gentle traction, the fetal elbow is delivered followed by the delivery of the posterior shoulder. If this fails, it is recommended to rotate the fetus internally so that the anterior shoulder is now posterior and then repeated. However, this has been related to complications such as humerus fracture, especially when flexion of the elbow is impossible or difficult 26, 27, 28.

Jacquemier’s maneuver is recommended when the McRoberts maneuver combined with suprapubic pressure (Mazzanti maneuver) fails and it is not a primary maneuver 27, 28. In general, because of the difficulty of the maneuvers and the pain to the woman, an epidural anesthesia is mandatory.

A retrospective review revealed that the combination of the McRoberts maneuver, suprapubic pressure (Mazzanti maneuver), and posterior arm delivery (Jacquemier’s maneuver) resulted in successful delivery within four minutes in 95% of cases 24. Computer modeling suggests that delivery of the posterior arm results in the least amount of brachial plexus stretch compared with other maneuvers 29. Delivery of the posterior arm requires patience and communication to keep the patient calm. Training with a birth simulator will likely improve operator confidence and performance of this procedure.

An episiotomy may help depending on the size of the physician’s hands and ability to enter the posterior vagina, but it is not mandatory for this or any release maneuver 30. The physician should apply lubricant, compress all five fingers from the appropriate hand into a “duck-bill” shape, and gently maneuver the hand into the posterior vagina, under the baby (see a video of a posterior arm release). The physician should then slide the hand along the fetal chest, not the back, up to the fetal hip, or until the posterior hand is identified. Grasping the wrist by forming an OK sign with the physician’s thumb and index finger (Figure 4), he or she should flex the fetal elbow and slide the arm along the fetal chest to deliver from the posterior vagina. Using the operator’s fifth finger as a fulcrum by placing it along the fetal elbow may help.

If the posterior arm is tight against the vaginal sidewall and cannot be delivered, other methods of delivering the posterior shoulder can be used. The Menticoglou maneuver involves placing one finger from each hand under the posterior axilla and applying gentle traction along the curve of the pelvis to deliver the posterior shoulder 31. After the shoulder delivers, it should be easier to deliver the entire posterior arm. The posterior axilla sling traction maneuver uses a suction catheter or urinary catheter placed under the posterior shoulder axilla to apply downward traction to deliver the posterior shoulder 32. Alternatively, the physician can use the sling to rotate the posterior shoulder 180 degrees to anterior, similar to the Woods maneuver. A description and video of this technique can be accessed at https://www.ajog.org/article/S0002-9378(15)00161-1/fulltext

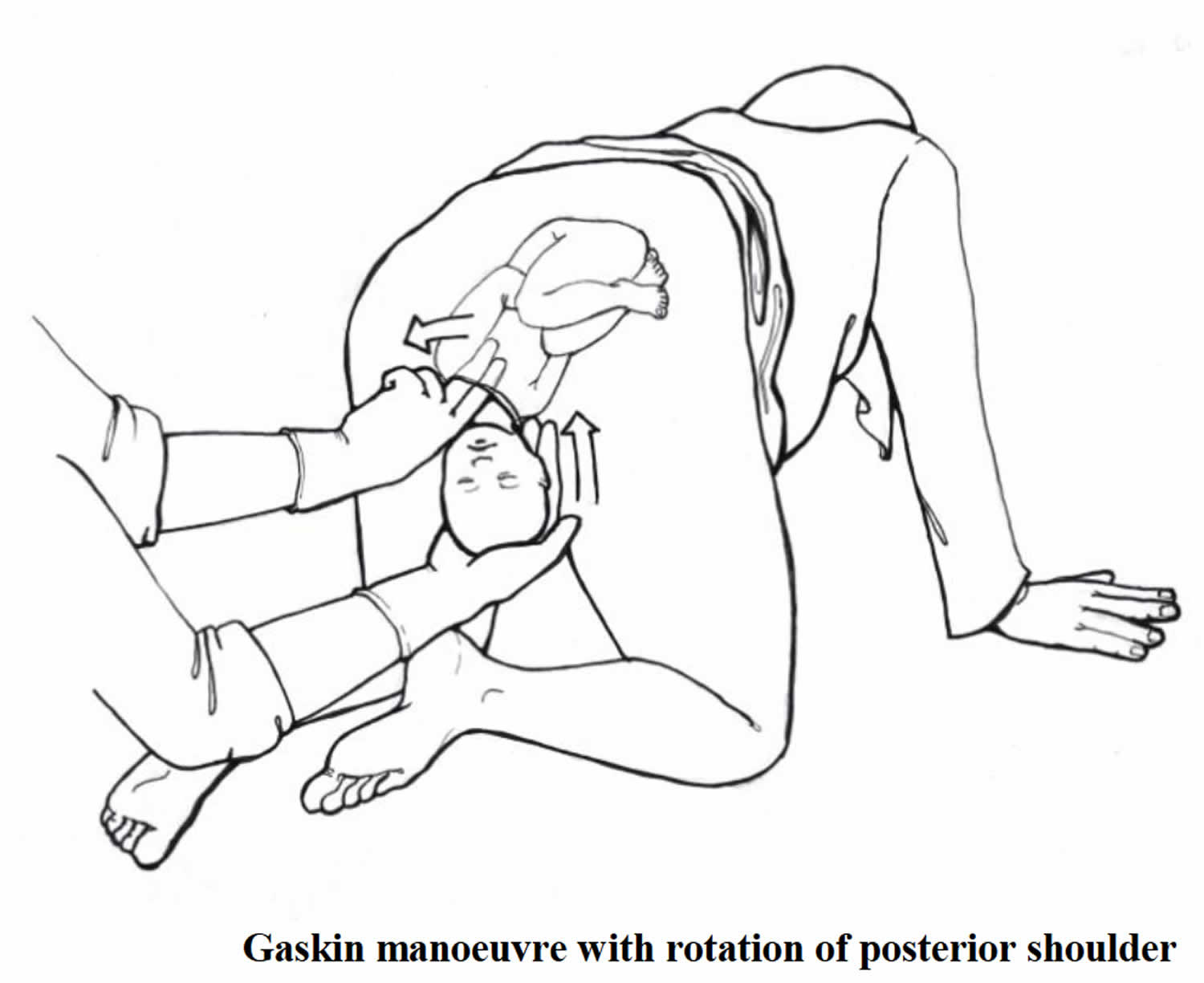

Additional maneuvers include rotational methods (e.g., Rubin 2, the Woods or reverse Woods [corkscrew] maneuvers) and rolling the patient to her hands and knees (Gaskin all-fours maneuver).

Figure 4. McRoberts maneuver

[Source 1 ]Figure 5. Suprapubic pressure or Mazzanti maneuver (an assistant applies firm downward or oblique pressure just above the symphysis pubis toward the side the infant is facing)

[Source 1 ]Figure 6. Posterior arm release (Jacquemier’s maneuver)

Rubin 2 maneuver

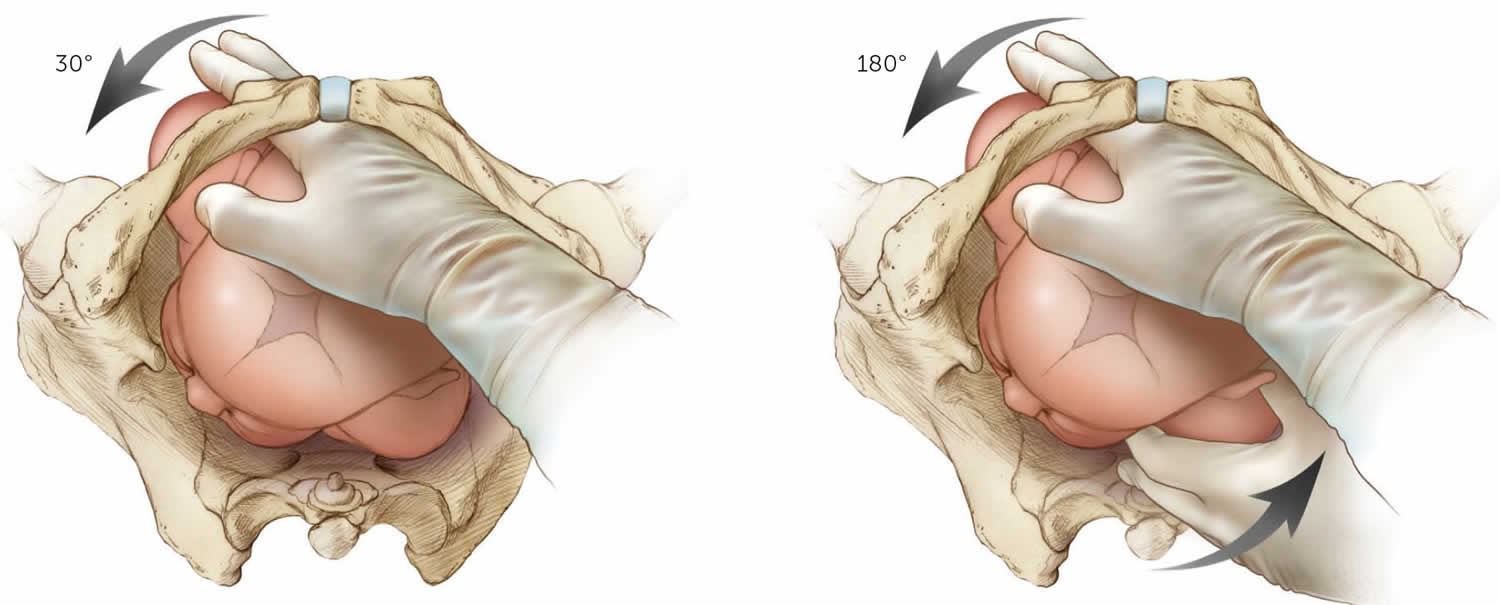

To perform the Rubin 2 maneuver, the physician places two fingers on the back (posterior) side of the anterior fetal shoulder into the vagina to push the scapula of the anterior fetal shoulder toward the fetal face to attempt to rotate the fetus 30 degrees toward the fetal face (Figure 7).

Figure 7. Rubin 2 maneuver (left) and Woods maneuver (right)

Woods maneuver (Woods screw maneuver)

The Woods maneuver also known as Woods screw maneuver, is a screw-like maneuver that combines the hand placement for the Rubin 2 maneuver with two fingers on the anterior aspect of the posterior fetal shoulder with the intent of rotating the fetus 180 degrees (i.e., rotating the posterior shoulder to the anterior position) (Figure 7). Success of Woods maneuver allows easy delivery of that shoulder once past the symphysis pubis.

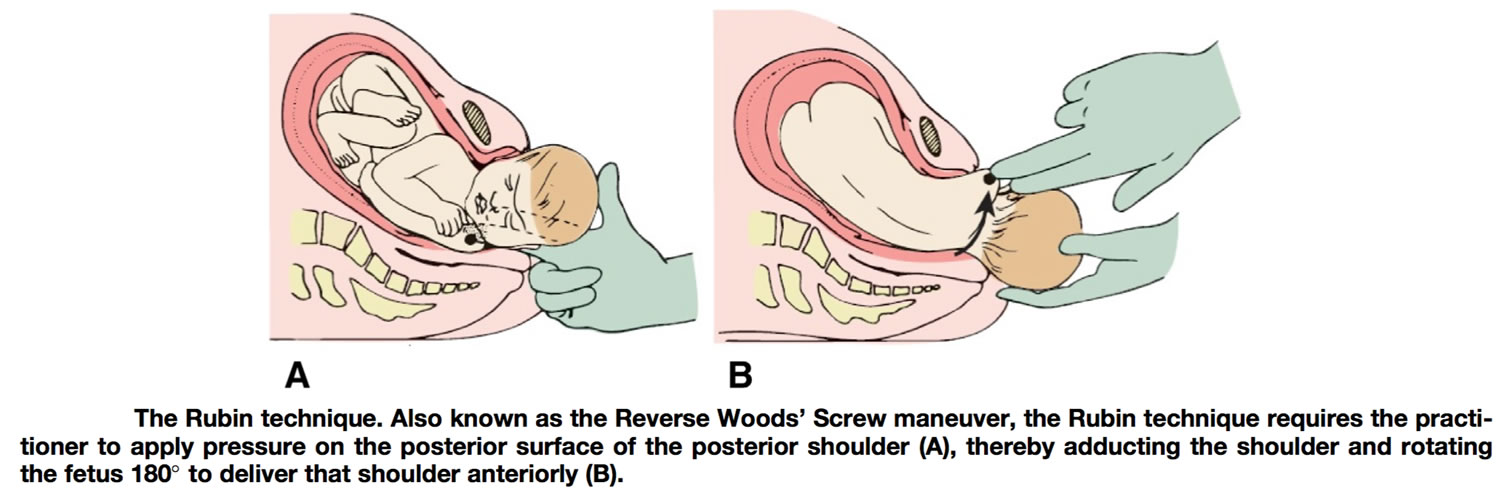

Reverse Wood’s Screw (Rubin maneuver)

For the reverse Woods maneuver or Rubin maneuver, insert two fingers into the vagina posteriorly and apply pressure to the posterior surface of the posterior shoulder to rotate the infant 180 degrees. An episiotomy may be helpful for the Woods maneuvers to be able to gain access with two hands.

Figure 8. Reverse Woods screw maneuver

Gaskin maneuver

The Gaskin all-fours maneuver requires the patient to roll onto her hands and knees and gentle downward traction is applied to the baby’s head. This had an 83% success rate as the sole maneuver used in one series 33. The Gaskin all-fours maneuver may be more difficult if the patient is fatigued or has neuraxial anesthesia.

Figure 9. Gaskin maneuver (‘all-fours’ position)

Catastrophic shoulder dystocia maneuvers

Catastrophic shoulder dystocia maneuvers

If McRoberts maneuver, suprapubic pressure, and posterior arm delivery, Rubin 2 maneuver, Woods screw maneuver, reverse Woods maneuver or Rubin maneuver and Gaskin maneuvers do not result in delivery, options include performing the maneuvers again (see shoulder dystocia management algorithm in Figure 2 above) or enlisting assistance from another experienced physician who might try the previously attempted maneuvers again or who can collaborate to attempt less proven maneuvers, such as abdominal rescue, cephalic replacement (Zavanelli maneuver), and intentional clavicular fracture 11, 34, 35.

If nothing has worked to this point and all the procedures have been tried again, then some health care providers have suggested:

Zavanelli maneuver

When all techniques have failed, then the Zavanelli maneuver is suggested 14, 36, 37. The Zavanelli maneuver came into popular use in the early 1980s. The mother receives a tocolytic of 0.25 mg terbutaline subcutaneously or some other uterine relaxant 28. The fetal head should then be turned in the anterior occipital position, flexed from the extended position and pressure is the applied to the vertex to push back the head into the pelvis, reversing the movements of the preceding mechanism of labor. The head then is held in place by an assistant until cesarean section is accomplished 38. A cesarean section is performed immediately 37, 39. During the procedure it is mandatory to monitor the fetal heart rate 28.

There are case reports and case series detailing the use of Zavanelli maneuver, with mixed results 40:883-4.)), 41, 42. During the time before delivery, death or permanent peripheral or central nervous system injury may have already occurred 40:883-4.)). However, the Zavanelli maneuver can be successful, with excellent maternal or neonatal outcome 41. Because it is done so infrequently, and not all cases are reported, it is impossible to evaluate the relative risks and benefits of the Zavanelli maneuver 43.

Figure 10. Zavanelli maneuver

[Source 44 ]Intentional clavicular fracture

When more conservative approaches fail, intentional fracture of the clavicle may relieve a shoulder dystocia 39. The posterior clavicle is generally most accessible. Careful technique is required to avoid injuring the subclavian vessels or the apex of the lung. This is achieved by applying pressure to the clavicle of the fetus. This technique reduces the bisacromial diameter, but the clinician must be very careful so not to injure the underlying vascular fracture or even the lung fracture 39. In fact, spontaneous clavicle fractures are not often associated with brachial plexus injury, probably because the collapse of the shoulder girdle precludes the problem 43.

Symphysiotomy

Symphysiotomy performed rarely in the developed world is only recommended when all other techniques have failed 45, 39, 20, 43. In fact, Menticoclou 27 states that it should be applied only after 5 minutes if the shoulder dystocia has not been solved yet and the other maneuvers, even the Zavanelli, have failed. Symphysiotomy has been used as a last resort. Symphysiotomy involves the surgical division of the fibrous tissue and cartilage of the pubic symphysis in order to increase the pelvic diameters 39, 20, 43. However, it should be avoided because the separation of the pubic symphysis if not restored has been related to complications such as bladder, urethral and vaginal injury. These injuries could lead later to urinary incontinence, chronic pelvic pain, chronic osteitis pubis and unstable pelvis 39, 20, 43.

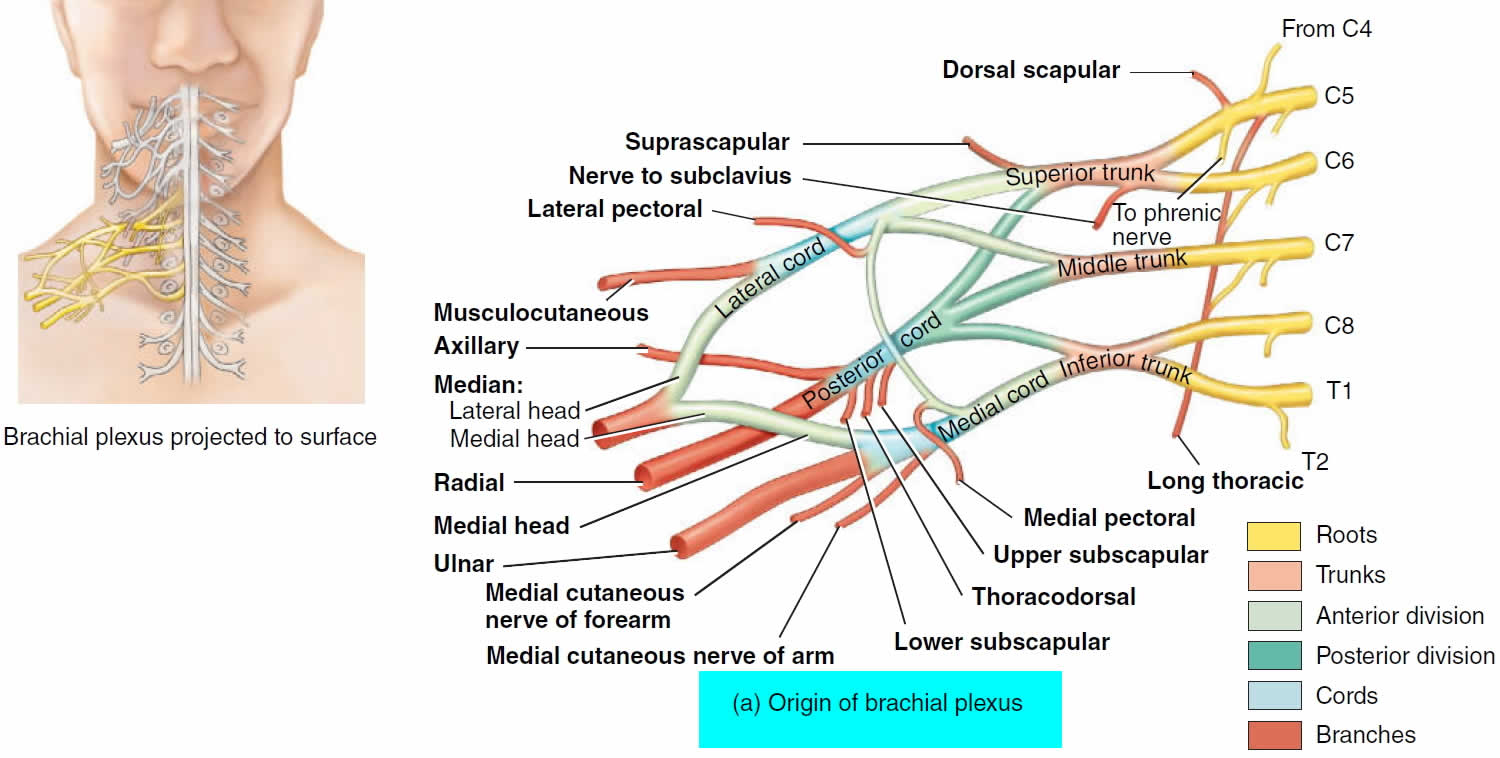

Brachial plexus injury shoulder dystocia treatments

Symptoms of a brachial plexus injury may include a limp or paralyzed arm; lack of muscle control in the arm, hand, or wrist; and a lack of feeling or sensation in the arm or hand. In infants, brachial plexus injuries may happen during birth if the baby’s shoulder is stretched during passage in the birth canal. Birth brachial plexus injury is also known as obstetric brachial plexus injury incidence varies between 0.15 and 3 per 1000 live births in various series and countries 46. Birth brachial plexus injury (obstetric brachial plexus palsy) is caused by traction to the brachial plexus during labour 47. In the majority of cases delivery of the upper shoulder is blocked by the mother’s pubic symphysis (shoulder dystocia). If additional traction is applied to the child’s head, the angle between the neck and the shoulder is forcefully widened, overstretching the ipsilateral brachial plexus. Injury to the superior roots of the brachial plexus (C5–C6) may result from forceful pulling away of the head from the shoulder, as might occur from excessive stretching of an infant’s neck during childbirth. The resulting traction injury may vary from neurapraxia (a temporary loss of motor and sensory function due to blockage of nerve conduction) or axonotmesis (a more severe injury where the nerve axons and their myelin sheath are damaged but the endoneurium, perineurium and epineurium remain intact) to neurotmesis (the most serious nerve injury both the nerve and the nerve sheath are disrupted. While partial recovery may occur, complete recovery is impossible) and avulsion of rootlets (most severe form of brachial plexus injury where the nerve roots are torn off the spinal cord) from the spinal cord. Most individuals with neuropraxia injuries recover spontaneously with a 90-100% return of function.

Based on the location of the nerve damage, brachial plexus injuries can affect part of or the entire arm. For example, musculocutaneous nerve damage weakens elbow flexors, median nerve damage causes proximal forearm pain, and paralysis of the ulnar nerve causes weak grip and finger numbness. In some cases, these injuries can cause total and irreversible paralysis. In less severe cases, these injuries limit use of these limbs and cause pain.

The cardinal signs of brachial plexus injury are weakness in the arm, diminished reflexes, and corresponding sensory deficits.

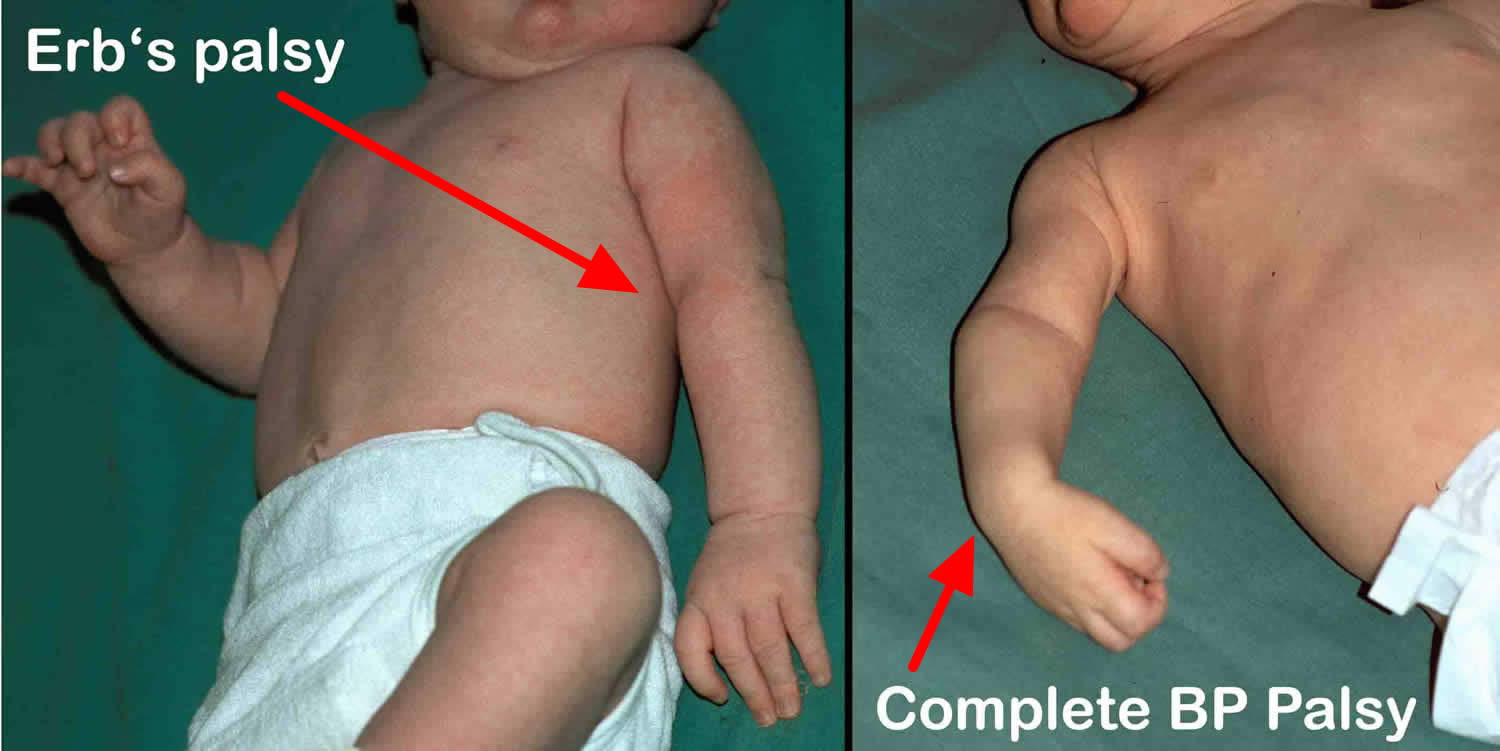

- Erb’s palsy (Erb-Duchenne palsy) caused by injury to the superior roots of the brachial plexus (C5–C6) (Figure 13). The position of the limb, under such conditions, is characteristic: the arm hangs by the side and is rotated medially; the forearm is extended and pronated. The arm cannot be raised from the side; all power of flexion of the elbow is lost, as is also supination of the forearm — “waiter’s tip position”. There is loss of sensation along the lateral side of the arm.

- Klumpke’s paralysis, also called Dejerine-Klumpke palsy refers to paralysis of the lower brachial plexus (C8 and T1) (Figure 14). Klumpke’s paralysis typically involve the muscles of the forearm and hand, a characteristic sign is the clawed hand, due to loss of function of the ulnar nerve and the intrinsic muscles of the hand it supplies. Involvement of T1 may result in Horner’s syndrome, with ptosis (droop upper eyelid), enophthalmos (sinking of the eyeball into the face), anhidrosis (decreased sweating on the affected side of the face) and miosis (excessive constriction of the pupil of the eye).

The site and type of brachial plexus injury determines the prognosis. For avulsion and rupture injuries, there is no potential for recovery unless surgical reconnection is made in a timely manner. The potential for recovery varies for neuroma and neuropraxia injuries. Most individuals with neuropraxia injuries recover spontaneously with a 90-100% return of function.

Any suspected brachial plexopathy should undergo a trial of observation and daily passive exercises to await the return of function. The most important consideration in early non-operative management is maintaining the passive motion of the extremity while awaiting nerve function return.

At 3 to 9 months of age, surgical intervention may be considered. Nerve grafting is indicated for patients without antigravity biceps function if the nerve injury is postganglionic, while preganglionic nerve injures better treated with nerve transfer or neurotization.

To prevent glenohumeral dysplasia from persistent internal rotation of the humerus, tendon transfers or tendon lengthening procedures may be considered. The Hoffer procedure is a transfer of the latissimus dorsi and teres major to external rotators of the humerus. Pectoralis major and subscapularis tendon lengthening procedures can serve to lessen the internal rotation forces that remain unopposed in upper lesions. Alternatively, practitioners may consider a Wickstrom osteotomy, which serves as a proximal humeral derotation osteotomy to combat the internal rotation contracture present in such plexopathies 48, 49.

Serial nighttime elbow extension splinting is the mainstay of treatment for elbow flexion contractures, but operative capsular release and biceps tendon lengthening may be considered for persistent contraction 50.

A number of tendon transfers distally may be employed to treat deficiencies in the hand and wrist. Wrist drop is most frequently treated with pronator teres to extensor carpi radialis brevis (ECRB) transfer. Loss of finger extension may be treated with the transfer of flexor carpi radialis or ulnaris (FCR or FCU) to extensor digitorum communis (EDC). Loss of thumb abduction may be treated with extensor indicis proprius (EIP) to abductor pollicis brevis (APB) transfer.

Figure 11. Brachial plexus

Figure 12. Brachial plexus origin and nerve branches

Figure 13. Erb’s palsy (C5-C6 nerve damage) waiter’s tip position

Figure 14. Klumpke’s paralysis (C8-T1 nerve damage) claw hand

Shoulder dystocia prognosis

Most babies recover from shoulder dystocia very well. But because they may have been injured or deprived of oxygen, they may need to be watched more closely or spend time in the neonatal intensive care unit (NICU). Some babies will need physiotherapy, and you may need help with breastfeeding if your baby has been injured.

Annika et al. 51 has shown that by the age of three months, half of all babies born with shoulder dystocia are functioning completely. By the age of 18 months, 82% of babies regain full function.

If your child suffered a brachial plexus injury, the outcome is generally positive. But some interventions may affect your child’s long-term outcome. They may have trouble with fine motor skills and other uses of their affected limb. More than 90% of these injuries improve within six to 12 months. Less than 10% result in permanent injury 17.

If you had a vaginal or perineal tear or hemorrhage, it will take some time for you to recover. It can also be hard emotionally if you have had a difficult childbirth. You might feel shocked, guilty or worried about your baby. Midwives, your doctor or a maternal child health nurse can help you deal with these feelings.

Your doctor will talk to you about why the shoulder dystocia might have happened. If you’ve had a baby with shoulder dystocia, your chances of the condition occurring again increase by 15%. Be sure to discuss this with your healthcare provider if you plan on having more children. If you had a C-section due to shoulder dystocia, vaginal birth after cesarean (VBAC) isn’t recommended, your doctor may suggest you consider a planned cesarean next time around.

Simulation-based training has decreased the overall rate of shoulder dystocia and other obstetric-related complications 52, 53, 54.

References- Shoulder Dystocia: Managing an Obstetric Emergency. Am Fam Physician. 2020;102(2):84-90. https://www.aafp.org/pubs/afp/issues/2020/0715/p84.html

- Resnik R. Management of shoulder girdle dystocia. Clin Obstet Gynecol. 1980 Jun;23(2):559-64. doi: 10.1097/00003081-198006000-00024

- Sentilhes L, Sénat MV, Boulogne AI, Deneux-Tharaux C, Fuchs F, Legendre G, Le Ray C, Lopez E, Schmitz T, Lejeune-Saada V. Shoulder dystocia: guidelines for clinical practice from the French College of Gynecologists and Obstetricians (CNGOF). Eur J Obstet Gynecol Reprod Biol. 2016 Aug;203:156-61. doi: 10.1016/j.ejogrb.2016.05.047

- Hankins GD, Clark SL. Brachial plexus palsy involving the posterior shoulder at spontaneous vaginal delivery. Am J Perinatol. 1995 Jan;12(1):44-5. doi: 10.1055/s-2007-994398

- Executive summary: Neonatal brachial plexus palsy. Report of the American College of Obstetricians and Gynecologists’ Task Force on Neonatal Brachial Plexus Palsy. Obstet Gynecol. 2014 Apr;123(4):902-4. doi: 10.1097/01.AOG.0000445582.43112.9a

- Beall MH, Spong C, McKay J, Ross MG. Objective definition of shoulder dystocia: a prospective evaluation. Am J Obstet Gynecol. 1998 Oct;179(4):934-7. doi: 10.1016/s0002-9378(98)70191-7

- Tsur A, Sergienko R, Wiznitzer A, Zlotnik A, Sheiner E. Critical analysis of risk factors for shoulder dystocia. Arch Gynecol Obstet. 2012 May;285(5):1225-9. doi: 10.1007/s00404-011-2139-8

- Bingham J, Chauhan SP, Hayes E, Gherman R, Lewis D. Recurrent shoulder dystocia: a review. Obstet Gynecol Surv. 2010 Mar;65(3):183-8. doi: 10.1097/OGX.0b013e3181cb8fbc

- Zhang, C, Wu, Y, Li, S, Zhang, D. Maternal prepregnancy obesity and the risk of shoulder dystocia: a meta-analysis. BJOG 2018; 125: 407– 413. https://doi.org/10.1111/1471-0528.14841

- Ouzounian JG, Gherman RB. Shoulder dystocia: are historic risk factors reliable predictors? Am J Obstet Gynecol. 2005 Jun;192(6):1933-5; discussion 1935-8. doi: 10.1016/j.ajog.2005.02.054

- Practice Bulletin No 178: Shoulder Dystocia. Obstet Gynecol. 2017 May;129(5):e123-e133. doi: 10.1097/AOG.0000000000002043

- Gupta M, Hockley C, Quigley MA, Yeh P, Impey L. Antenatal and intrapartum prediction of shoulder dystocia. Eur J Obstet Gynecol Reprod Biol. 2010 Aug;151(2):134-9. doi: 10.1016/j.ejogrb.2010.03.025

- Shields SG, Ratcliffe S. Chapter F: labor dystocia. In: Leeman L, Quinlan JD, Dresang LT, et al. Advanced Life Support in Obstetrics Provider Manual. 8th edition. American Academy of Family Physicians; 2017:1–14.

- Sentilhes L, Sénat MV, Boulogne AI, et al. Dystocie des épaules : recommandations pour la pratique clinique-Texte court. Shoulder dystocia: Guidelines for clinical practice-Short text. Article in French. J Gynecol Obstet Biol Reprod (Paris) 2015;44(10):1303–1310. doi: 10.1016/j.jgyn.2015.09.053

- Gherman RB, Goodwin TM, Souter I, Neumann K, Ouzounian JG, Paul RH. The McRoberts’ maneuver for the alleviation of shoulder dystocia: how successful is it? Am J Obstet Gynecol. 1997 Mar;176(3):656-61. doi: 10.1016/s0002-9378(97)70565-9

- Gherman RB, Ouzounian JG, Goodwin TM. Obstetric maneuvers for shoulder dystocia and associated fetal morbidity. Am J Obstet Gynecol. 1998 Jun;178(6):1126-30. doi: 10.1016/s0002-9378(98)70312-6

- Gherman RB, Ouzounian JG, Miller DA, Kwok L, Goodwin TM. Spontaneous vaginal delivery: a risk factor for Erb’s palsy? Am J Obstet Gynecol. 1998 Mar;178(3):423-7. doi: 10.1016/s0002-9378(98)70413-2

- Bingham J, Chauhan SP, Hayes E, Gherman R, Lewis D. Recurrent shoulder dystocia: a review. Obstet Gynecol Surv. 2010;65(3):183–188. doi: 10.1097/OGX.0b013e3181cb8fbc

- Shoulder Dystocia. https://my.clevelandclinic.org/health/diseases/22311-shoulder-dystocia

- Bothou A, Apostolidi DM, Tsikouras P, Iatrakis G, Sarella A, Iatrakis D, Peitsidis P, Gerente A, Anthoulaki X, Nikolettos N, Zervoudis S. Overview of techniques to manage shoulder dystocia during vaginal birth. Eur J Midwifery. 2021 Oct 20;5:48. doi: 10.18332/ejm/142097

- Shoulder Dystocia (Green-top Guideline No. 42). https://www.rcog.org.uk/media/ewgpnmio/gtg_42.pdf

- Sturzenegger K, Schäffer L, Zimmermann R, Haslinger C. Risk factors of uterine rupture with a special interest to uterine fundal pressure. J Perinat Med. 2017 Apr 1;45(3):309-313. doi: 10.1515/jpm-2016-0023

- Lurie S, Ben-Arie A, Hagay Z. The ABC of shoulder dystocia management. Asia Oceania J Obstet Gynaecol. 1994 Jun;20(2):195-7. doi: 10.1111/j.1447-0756.1994.tb00449.x

- Leung, T., Stuart, O., Suen, S., Sahota, D., Lau, T. and Lao, T. (2011), Comparison of perinatal outcomes of shoulder dystocia alleviated by different type and sequence of manoeuvres: a retrospective review. BJOG: An International Journal of Obstetrics & Gynaecology, 118: 985-990. https://doi.org/10.1111/j.1471-0528.2011.02968.x

- Collin A, Dellis X, Ramanah R, et al. La dystocie vraie des épaules: analyse de 14 cas traités par la manoeuvre de Jacquemier. Severe shoulder dystocia: study of 14 cases treated by Jacquemier’s maneuver. Article in French. J Gynecol Obstet Biol Reprod (Paris) 2008;37(3):283–290. doi: 10.1016/j.jgyn.2007.12.008

- Ansell L, Ansell DA, McAra-Couper J, Larmer PJ, Garrett NKG. Axillary traction: An effective method of resolving shoulder dystocia. Aust N Z J Obstet Gynaecol. 2019;59(5):627–633. doi: 10.1111/ajo.13029

- Menticoglou S. Shoulder dystocia: incidence, mechanisms, and management strategies. Int J Womens Health. 2018;10:723–732. doi: 10.2147/IJWH.S175088

- Rodis JF. Shoulder dystocia: Intrapartum diagnosis, management, and outcome. https://www.uptodate.com/contents/shoulder-dystocia-intrapartum-diagnosis-management-and-outcome

- Grimm MJ, Costello RE, Gonik B. Effect of clinician-applied maneuvers on brachial plexus stretch during a shoulder dystocia event: investigation using a computer simulation model. Am J Obstet Gynecol. 2010 Oct;203(4):339.e1-5. doi: 10.1016/j.ajog.2010.05.002

- Sagi-Dain L, Sagi S. The role of episiotomy in prevention and management of shoulder dystocia: a systematic review. Obstet Gynecol Surv. 2015 May;70(5):354-62. doi: 10.1097/OGX.0000000000000179

- Menticoglou SM. A modified technique to deliver the posterior arm in severe shoulder dystocia. Obstet Gynecol. 2006 Sep;108(3 Pt 2):755-7. doi: 10.1097/01.AOG.0000232505.65290.04

- Cluver CA, Hofmeyr GJ. Posterior axilla sling traction for shoulder dystocia: case review and a new method of shoulder rotation with the sling. Am J Obstet Gynecol. 2015 Jun;212(6):784.e1-7. doi: 10.1016/j.ajog.2015.02.025

- Bruner JP, Drummond SB, Meenan AL, Gaskin IM. All-fours maneuver for reducing shoulder dystocia during labor. J Reprod Med. 1998 May;43(5):439-43.

- O’Shaughnessy MJ. Hysterotomy facilitation of the vaginal delivery of the posterior arm in a case of severe shoulder dystocia. Obstet Gynecol. 1998 Oct;92(4 Pt 2):693-5. doi: 10.1016/s0029-7844(98)00153-7

- Sandberg EC. The Zavanelli maneuver: 12 years of recorded experience. Obstet Gynecol. 1999 Feb;93(2):312-7. doi: 10.1016/s0029-7844(98)00340-8

- Sentilhes L, Sénat MV, Boulogne AI, et al. Shoulder dystocia: guidelines for clinical practice from the French College of Gynecologists and Obstetricians (CNGOF) Eur J Obstet Gynecol Reprod Biol. 2016;203:156–161. doi: 10.1016/j.ejogrb.2016.05.047

- Hill MG, Cohen WR. Shoulder dystocia: prediction and management. Womens Health (Lond) 2016;12(2):251–261. doi: 10.2217/whe.15.103

- Naef RW 3rd, Morrison JC. Guidelines for management of shoulder dystocia. J Perinatol. 1994 Nov-Dec;14(6):435-41.

- Davis DD, Roshan A, Canela CD, et al. Shoulder Dystocia. [Updated 2022 Sep 4]. In: StatPearls [Internet]. Treasure Island (FL): StatPearls Publishing; 2022 Jan-. Available from: https://www.ncbi.nlm.nih.gov/books/NBK470427

- Graham JM, Blanco JD, Wen T, Magee KP. The Zavanelli maneuver: a different perspective. Obstet Gynecol. 1992 May;79(5 ( Pt 2

- O’Leary JA. Cephalic replacement for shoulder dystocia: present status and future role of the Zavanelli maneuver. Obstet Gynecol. 1993 Nov;82(5):847-50.

- Sandberg EC. The Zavanelli maneuver extended: progression of a revolutionary concept. Am J Obstet Gynecol. 1988 Jun;158(6 Pt 1):1347-53. doi: 10.1016/0002-9378(88)90366-3

- Hill MG, Cohen WR. Shoulder dystocia: prediction and management. Womens Health (Lond). 2016;12(2):251-61. doi: 10.2217/whe.15.103

- Hall SP. The nurse’s role in the identification of risks and treatment of shoulder dystocia. J Obstet Gynecol Neonatal Nurs. 1997 Jan-Feb;26(1):25-32. https://doi.org/10.1111/j.1552-6909.1997.tb01504.x

- Goodwin TM, Banks E, Millar LK, Phelan JP. Catastrophic shoulder dystocia and emergency symphysiotomy. Am J Obstet Gynecol. 1997 Aug;177(2):463-4. doi: 10.1016/s0002-9378(97)70218-7

- Pondaag W, Malessy M, van Dijk JG, Thomeer R. Natural history of obstetric brachial plexus palsy: A systematic review. Dev Med Child Neurol. 2004;46:138–44. http://onlinelibrary.wiley.com/doi/10.1111/j.1469-8749.2004.tb00463.x/pdf

- Metaizeau JP, Gayet C, Plenat F. (1979) Les lesions obstétricales du plexus brachial. Chir Pediatr 20:159–163. (In French).

- Waters PM, Bae DS. The early effects of tendon transfers and open capsulorrhaphy on glenohumeral deformity in brachial plexus birth palsy. J Bone Joint Surg Am. 2008 Oct;90(10):2171-9. doi: 10.2106/JBJS.G.01517

- Pearl ML. Shoulder problems in children with brachial plexus birth palsy: evaluation and management. J Am Acad Orthop Surg. 2009 Apr;17(4):242-54. doi: 10.5435/00124635-200904000-00005

- Ho ES, Roy T, Stephens D, Clarke HM. Serial casting and splinting of elbow contractures in children with obstetric brachial plexus palsy. J Hand Surg Am. 2010 Jan;35(1):84-91. doi: 10.1016/j.jhsa.2009.09.014

- Annika J, Paul U, Anna-Lena L. Obstetric brachial plexus palsy – A prospective, population-based study of incidence, recovery and long-term residual impairment at 10 to 12 years of age. Eur J Paediatr Neurol. 2019 Jan;23(1):87-93. doi: 10.1016/j.ejpn.2018.06.006

- Bullough AS, Wagner S, Boland T, Waters TP, Kim K, Adams W. Obstetric team simulation program challenges. J Clin Anesth. 2016 Dec;35:564-570. doi: 10.1016/j.jclinane.2016.08.019

- SØRENSEN, J.L., LØKKEGAARD, E., JOHANSEN, M., RINGSTED, C., KREINER, S. and MCALEER, S. (2009), The implementation and evaluation of a mandatory multi-professional obstetric skills training program. Acta Obstetricia et Gynecologica Scandinavica, 88: 1107-1117. https://doi.org/10.1080/00016340903176834

- Shaw-Battista, J., Belew, C., Anderson, D. and van Schaik, S. (2015), Successes and Challenges of Interprofessional Physiologic Birth and Obstetric Emergency Simulations in a Nurse-Midwifery Education Program. Journal of Midwifery & Women’s Health, 60: 735-743. https://doi.org/10.1111/jmwh.12393