Spina bifida

Spina bifida also called spinal dysraphism is a neural tube defect in which the neural tube, a layer of cells that ultimately develops into the brain and spinal cord, fails to close completely during the first few weeks of embryonic development 1, 2. “Spina” means the bones of the spinal column or the vertebrae and “bifida” means in two parts 2. As a result, when the spine forms, the bones of the spinal column or the vertebrae do not close completely around the developing nerves of the spinal cord. Part of the spinal cord may stick out through an opening in the spine, leading to permanent nerve damage. Because spina bifida is caused by abnormalities of the neural tube, it is classified as a neural tube defect 3. Spina bifida is one of the most common types of neural tube defect, affecting an estimated 1 in 2,500 to 2.7 to 3.8 per 10,000 newborns worldwide 4. Furthermore, 90-95% of those with spina bifida have no previous family history 5. Spina bifida is slightly more common in females than males. For unknown reasons, the prevalence of spina bifida varies among different geographic regions and ethnic groups. In the United States, spina bifida occurs more frequently in Hispanics and non-Hispanic whites than in African Americans.

The neural tube is that part of the very young fetus which later develops into the central nervous system and the structures surrounding it. The neural tube comprises the brain and spinal cord, their three layers of lining called the meninges as well as the vertebrae (backbone) and skull. The baby’s brain and spine develop from a neural tube in the first four weeks of pregnancy. Spina bifida is caused when the neural tube does not fully develop, leaving a gap or split in the spine. Spina bifida can affect how your baby’s brain, spine, spinal cord and meninges develop. Meninges are the tissues that cover and protect the brain and the spinal cord. Most neural tube defects can be prevented by taking folic acid before and after conception.

The total incidence of neural tube defects is approximately 1 in 700 live births in Caucasian people. The incidence amongst African-Americans is less than 1 in 3000 live births. There is no particular predominance for male or female newborns.

Spina bifida can range from mild to severe, depending on the type of defect, size, location and complications. When early treatment for spina bifida is necessary, it’s done surgically, although such treatment doesn’t always completely resolve the problem.

Figure 1. Neural tube development

Around the third week of pregnancy a flat sheet of cells called the neural plate starts to change shape and forms a groove. The process continues until a tube is formed. This tube is called the neural tube. If the process does not complete and an opening is left somewhere along the length of the neural tube then the result is what is called a neural tube defect. If the opening is in the top part of the tube which later forms the brain and skull, the defect is called anencephaly and it is always fatal.

If the opening is in the bottom part of the tube the defect is spina bifida. Because the bottom part of the neural tube develops into the spinal cord, meninges (linings) and vertebrae, any or all of these structures can be involved in the spina bifida.

Risk Factors

- Maternal folic acid deficiency has a strong correlation with neural tube defects.

- Maternal use of valproate in the 1st trimester may be associated with spina bifida, however the risk of epilepsy in pregnancy outweighs not using medication in most cases.

- Previous children with spina bifida is associated with an increased risk of spia bifida – this suggests there may be some genetic component to this disease (in the absence of ongoing environmental factors).

- It should be noted that over ninety percent of cases of spina bifida, the pregnancy is classified ‘low risk’.

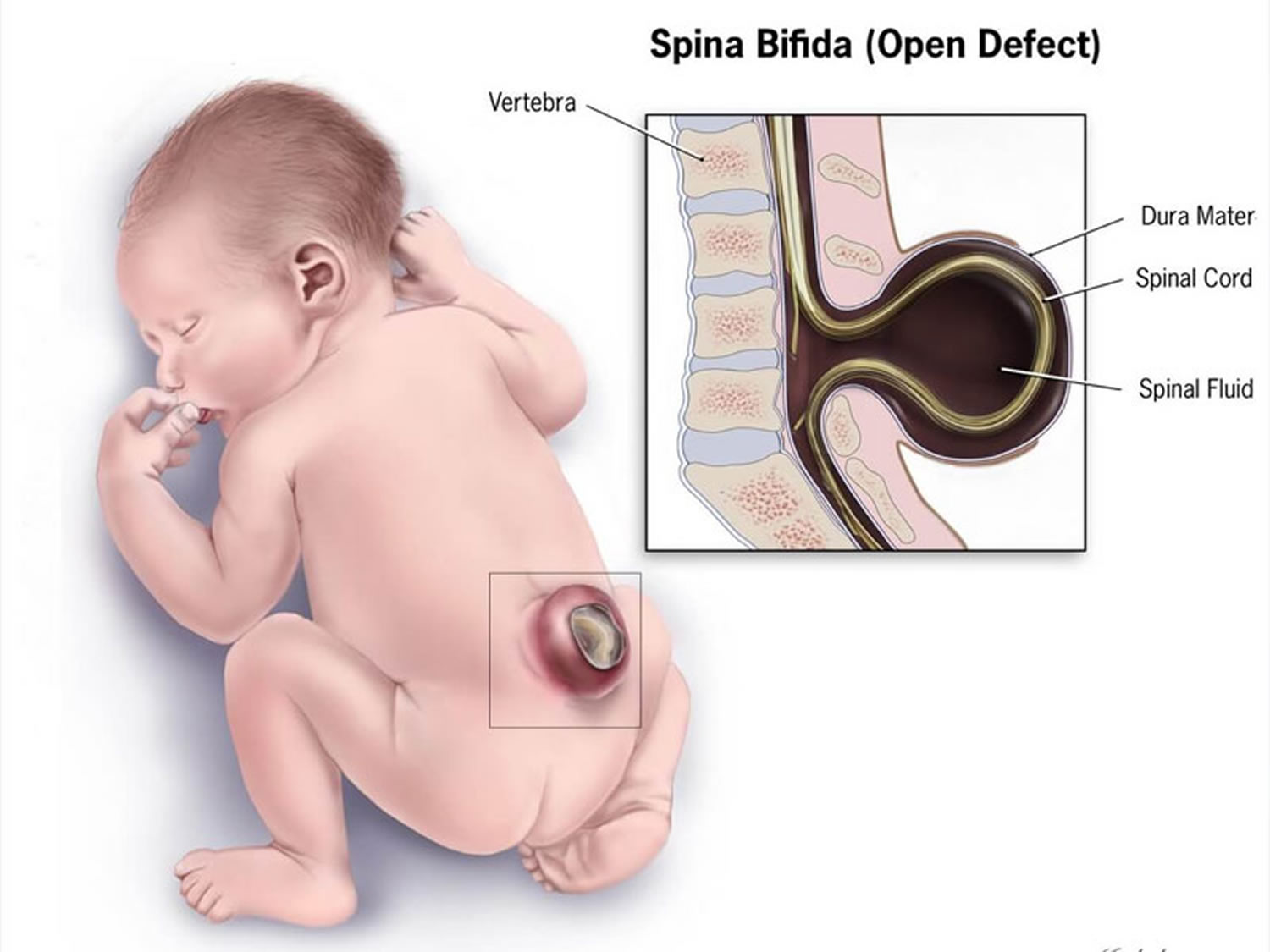

Where the spinal cord and meninges (linings) protrude into a sac on the back which is exposed, it is called meningomyelocele or sometimes myelomeningocoele.

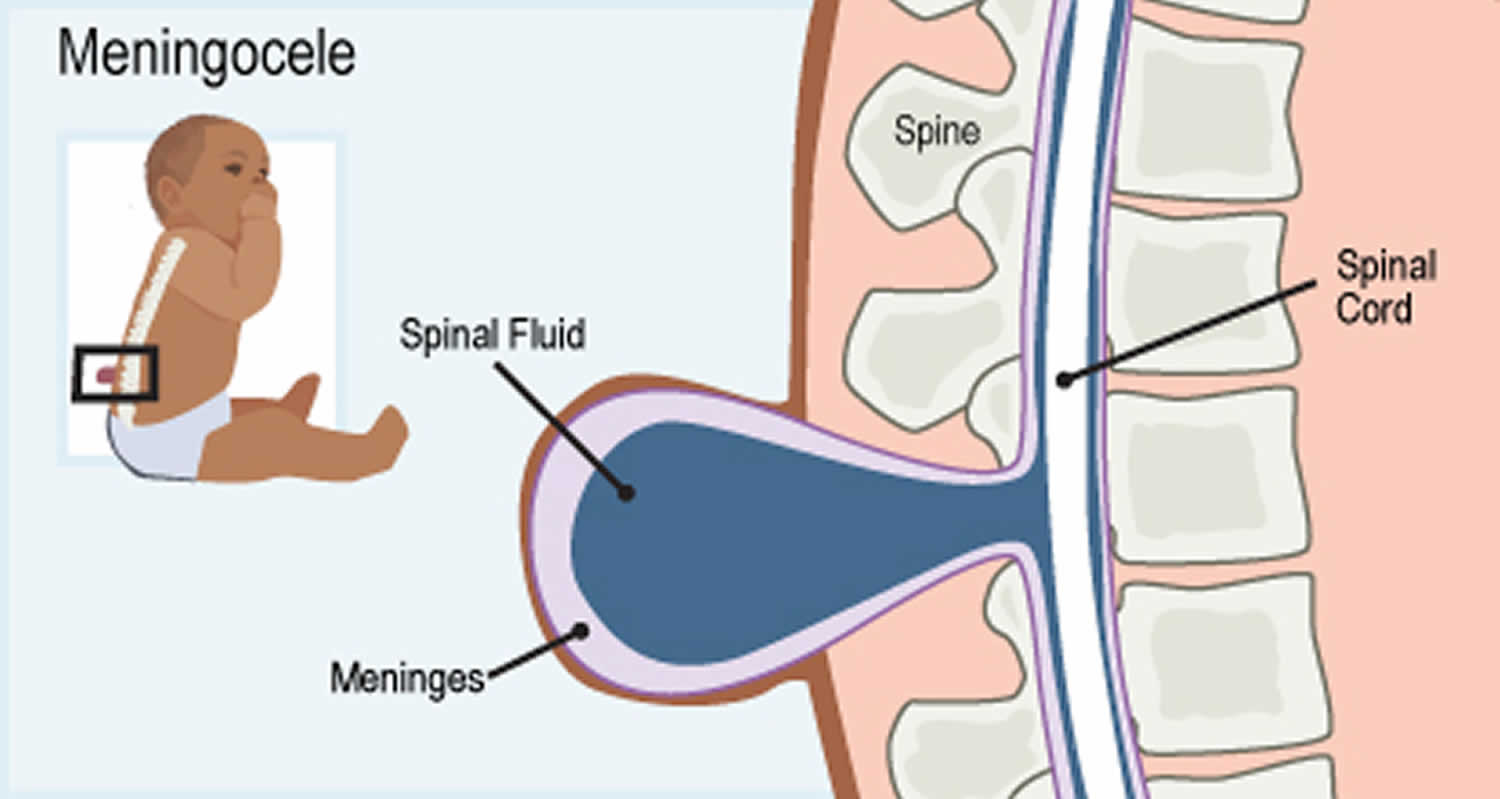

Where the meninges, but not the spinal cord, protrude through the opening in the vertebrae into an exposed sac, the condition is called meningocele. The sac is exposed (not covered by skin) when the baby is born so these forms of spina bifida are very obvious at birth. They are also usually detected by ultrasound when scans are taken in the 18th week of pregnancy.

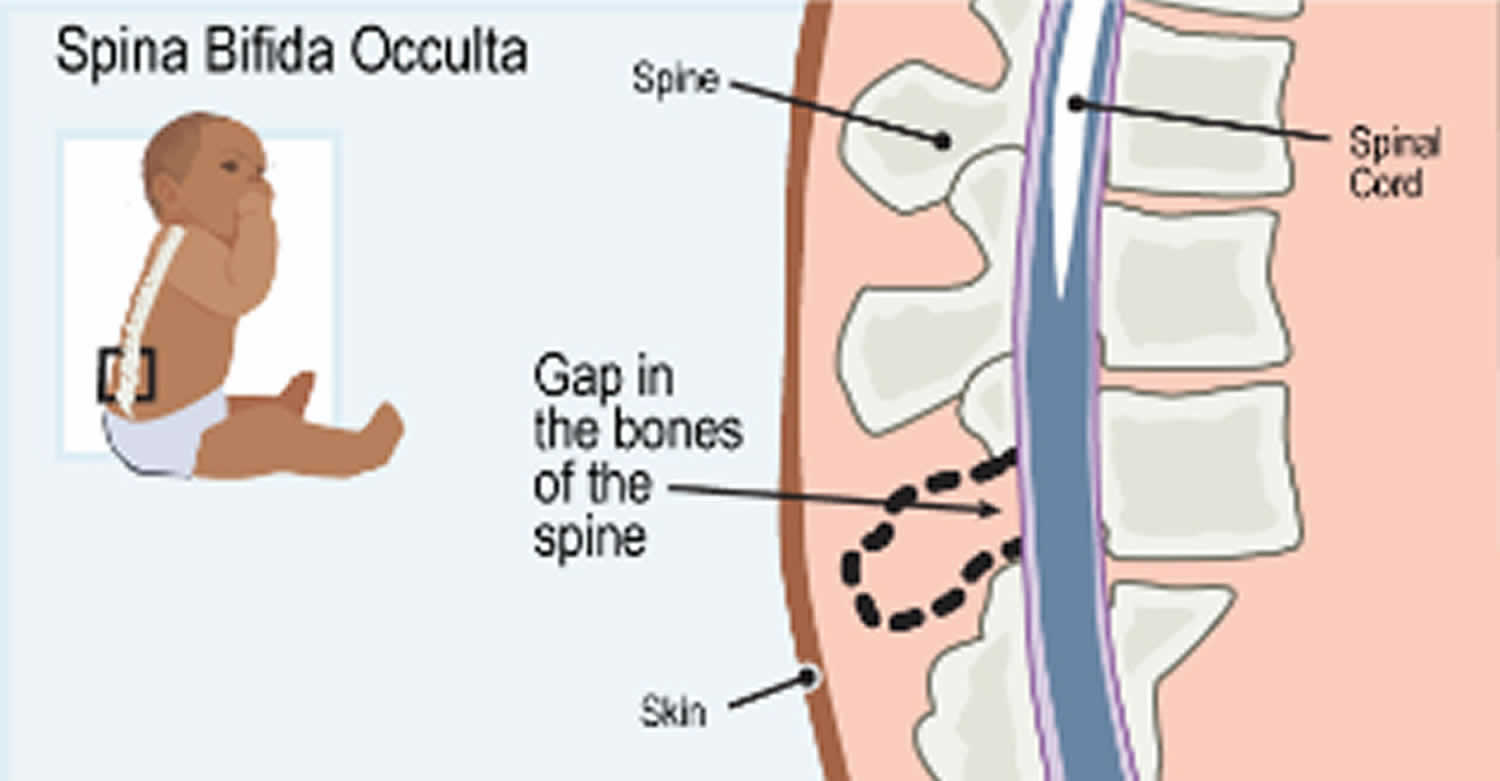

Where there is no exposed sac and the lesion is covered by skin the condition is called spina bifida occulta. The spinal cord and meninges are usually not affected. However the skin may show some unusual signs of underlying problems and this will be discussed later. Spina bifida occulta almost always occurs at the bottom of the spine – in the lumbar or sacral area.

Spina bifida can result in varying degrees of paralysis, loss of sensation, incontinence, spine and limb problems and in some cases cognitive impairment. However it should be noted that more than eighty percent of patients with spina bifida have a normal intelligence.

Early problems that may occur predominantly involve infection at the source of the lesion. The infection may spread to the central nervous system if left untreated. The spinal cord may also tether causing further neurological deterioration. Treatment may involve surgery, but it depends on the severity of the condition.

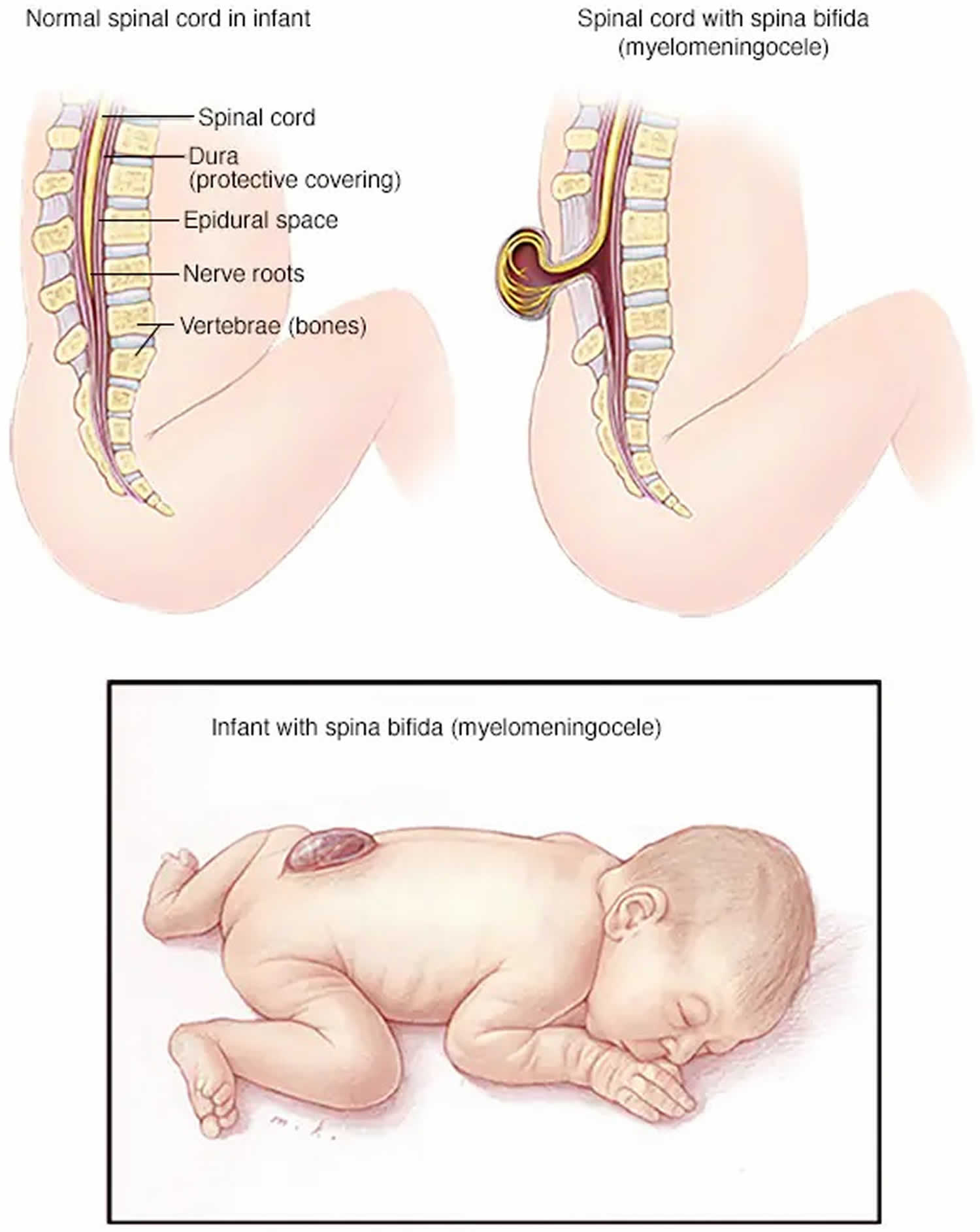

Figure 2. Spina bifida

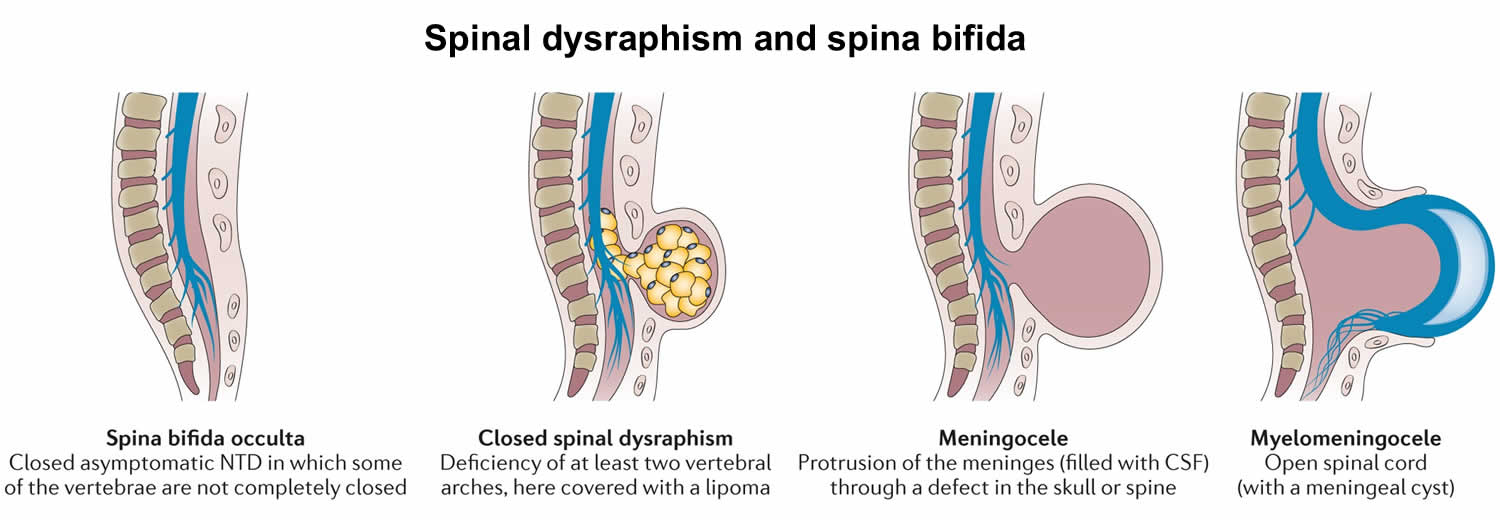

Spina bifida types

Spina bifida types

Spina bifida can occur in different forms:

- Spina bifida occulta,

- Meningocele

- Myelomeningocele (spina bifida cystica).

The severity of spina bifida depends on the type, size, location and complications.

Spina bifida can be broadly divided into two different clinicoradiological entities 6, 7:

- Open spina bifida previously called spina bifida aperta or cystica: occurs when the cord and its covering communicate with the outside; no skin or tissues cover the sac:

- Myelomeningocele (98% of open spina bifida). Myelomeningocele is a spina bifida in which the spinal cord and its contents herniate through a congenital bony defect in the posterior elements.

- Myelocele

- Hemimyelomeningocele

- Hemimyelocele

- Closed spina bifida previously called spina bifida occulta: occurs when the spinal cord is covered by other normal mesenchymal elements

- With subcutaneous mass

- lipoma with dural defect

- lipomyelomeningocele

- lipomyelocele/lipomyeloschisis

- terminal myelocystocele

- meningocele

- limited dorsal myeloschisis

- Without subcutaneous mass

- posterior spina bifida (isolated defect of the posterior neural arch of vertebra)

- intradural lipoma

- filar lipoma

- tight filum terminale

- persistent terminal ventricle

- disorders of midline notochordal integration

- dorsal dermal sinus

- dorsal enteric fistula

- neurenteric cyst 5,6

- split cord malformations

- diastematomyelia

- diplomyelia

- disorders of notochordal formation

- caudal regression syndrome: a spectrum of structural defects of the caudal region. Malformations vary from isolated partial agenesis of the coccyx to lumbosacral agenesis 8

- Type 1: the conus medullaris is blunt and terminates above the normal level; there is sometimes an associated dilated central canal or a cerebrospinal fluid-filled cyst at the lower end of the conus; these patients have major sacral deformities

- Type 2: the conus medullaris is elongated and tethered by a thickened filum terminale or intraspinal lipoma and ends below the normal level. Neurologic disturbances are more severe in this group

- segmental spinal dysgenesis

- caudal regression syndrome: a spectrum of structural defects of the caudal region. Malformations vary from isolated partial agenesis of the coccyx to lumbosacral agenesis 8

- With subcutaneous mass

Spina bifida occulta

The term spina bifida occulta covers two different conditions and this can be very confusing. One of them is relatively harmless and common – an anatomical anomaly rather than a medical condition. The other condition is much less common but it can cause significant problems. It is similar to a mild form of spina bifida.

Spina bifida is Latin for split spine and occulta means hidden. So spina bifida occulta is a split in the spine hidden by skin. What this means is that at least one vertebra is malformed or has not developed fully. Nobody knows for sure but it is assumed that spina bifida occulta develops in a similar way to spina bifida.

Figure 3. Spina bifida occulta

Spina bifida occulta – the common form

Spina bifida occulta where the spinal cord or meninges are not involved is quite common. A few recent medical studies show that about 22% of people have spina bifida occulta. In this form of spina bifida occulta it is usually only one vertebra which has not formed completely and the opening is usually very narrow.

In theory, because the spinal cord and meninges are not involved in any way, this form of spina bifida should cause no problems. However, there is some medical evidence that older children with urinary problems and adults with spondylolysis are over-represented in the group of people with this type of spina bifida occulta. Spondyloysis is a crack or stress fracture of the back part of one of the vertebra and it is reasonably common.

The association between spina bifida occulta and these conditions does not necessarily mean that the spina bifida occulta causes urinary problems or spondylolysis. It might mean that some of the things which caused the neural tube to not close fully have also caused other things to happen and these have led to the other conditions. This is one of the areas regarding spina bifida occulta that medical research has yet to provide an answer.

Spina bifida occulta – a mild spina bifida type

This type of spina bifida occulta is sometimes called occult spinal dysraphism or closed spina bifida. For clarity, this type will be referred to as occult spinal dysraphism from this point on.

Occult spinal dysraphism differs from the common type of spina bifida occulta in that the spinal nerves and or meninges are mixed up in some way with their surrounding structures and this involvement causes complications. Unfortunately, it is not always easy to say with any certainty which type a person has. There seems to be a range of lesions with very obvious cases of harmless spina bifida occulta at one end and very obvious cases of occult spinal dysraphism at the other and a grey area in the middle. While MRI technology has gone a long way to shed light on what is happening at the site, it seems that there are a number of people with no apparent involvement of nerve tissue who do have complications.

While spina bifida occulta is very common, there are much fewer people who have occult spinal dysraphism. Estimations of the incidence vary from 1 in 250 to 1 in 5,000 of the general population. However, these figures may change as medical technology improves and the ability to detect what is happening at the lesion site improves. The condition may also be undiagnosed in many people. The incidence of occult spinal dysraphism may be found to be similar to the incidence of spina bifida in the way that it varies from one geographic area to another and from one racial group to another. It is usually just one vertebra that is involved with the common spina bifida occulta and if there are more involved then the diagnosis is more likely to be occult spinal dysraphism. Apart from the size of the defect and the number of vertebrae involved, there can be some telltale signs on the skin which are visible at birth which might give a clue that something unusual is going on underneath.

Spina bifida is caused by both environmental and genetic factors. Even though 9 out of 10 children with spina bifida are born to parents with no family history of spina bifida, there is a higher risk of a pregnancy being affected by a neural tube defect (anencephaly or spina bifida) where there is a family history. The risk is higher when the family relationship is closer. The same seems to be true for occult spinal dysraphism.

In a family where one child has some form of occult spinal dysraphism, any future children seem to have a similar risk (3.5%) of developing a neural tube defect. It is not clear whether the risk is only for occult spinal dysraphism or any type of neural tube defect.

As many as 80% of people with occult spinal dysraphism have at least one of these outward signs or herald marks. The signs include:

- A hairy patch in the middle of the lower back

- A fatty lump over the bottom of the spine

- A stork bite or hemangioma (a reddish or purple spot) on the skin

- A dimple or sinus (hole) above the level of the crease in the buttocks (Dimples below the level of the crease are common in newborns and are usually no cause for alarm)

- A pigmented area or birthmark over the bottom of the spine.

- A small tail

Occult spinal dysraphism can be very complex because it is not just one condition. It represents a number of conditions which can occur separately or in combination. Some of these conditions are:

- A tethered spinal cord where the lower end of the spinal cord is stuck or attached to surrounding bone or other structures. The spinal cord is usually free (to some extent) to move up and down within the spinal canal.

- A lipoma which is a fatty lump whose tissues are often interwoven with those of the spinal cord, making them very difficult to separate. Lipomas can also tether the spinal cord.

- Diastematomyelia where the spinal cord is split in two usually by a piece of abnormal bone or cartilage. This can also tether the spinal cord.

- A dermal sinus which is a connection between the spinal canal and the skin of the back.

All of these conditions can affect the functioning of the spinal cord i.e. its ability to send messages to and from the brain. The cord can become stretched which causes pain and the blood supply to the cells in the spinal cord can be affected with the result that the nerves lose their ability to function properly.

Complications of occult spinal dysraphism

Not everyone with occult spinal dysraphism will have complications. Sometimes the onset of signs and symptoms will be so gradual that they may not appear until adulthood. For most though, there will be some indications early in the person’s life that the nerves in the spine are not working as they should.

Some of these are:

- Foot deformity

- Weakness in the legs

- Reduced feeling or numbness in the legs or feet

- Back or leg pain

- Bladder infections

- Bladder incontinence

- Constipation

- Scoliosis or other orthopedic deformities.

All of these symptoms can be caused by conditions other than occult spinal dysraphism so it is important to see your doctor for thorough testing and an accurate diagnosis.

It is especially important to seek medical advice where the symptoms are progressing or getting worse. These changes may indicate that the spinal cord is tethered and an operation to untether the cord might be required.

Prevention

It has been known for a few decades that folic acid (vitamin B-9) when taken for a month prior to conception and for 3 months afterwards can reduce the risk of the baby developing a neural tube defect by up to 70%. For women with no family history of a neural tube defect the recommended dose is 600 micrograms (600 mcg) a day. For women with a family history, including them or their partner, the recommended dose is 4 milligrams a day.

Folic acid (called folate in its natural form) is available naturally in leafy green vegetables and some other foods. The levels consumed naturally do not always reach the recommended level for lowering the risk of a neural tube defect in affected pregnancy, so it is important for women of child bearing age to take a daily folic acid supplement. Because about half of all pregnancies in the US are unplanned, the recommendation is for all women of child bearing age to supplement their diet with a folic acid tablet.

Medical treatment

If is felt that medical intervention is required then treatment may involve untethering of the spinal cord. This procedure is performed by a neurosurgeon. Because of the way that the nerves are arranged in the lower spinal cord, it is very complex surgery and there is always a risk that some nerves or the spinal cord itself may be damaged. Because of this risk and the fact that there is no guarantee that the operation will be successful in removing the symptoms or even reducing them, many neurosurgeons will wait until the symptoms become relatively serious before operating. On the other hand some neurosurgeons will operate early to try to prevent symptoms from progressing. At the moment there does not seem to be any clear evidence that one approach is better than the other.

Depending on the type or severity of complications, it may be necessary to be treated by another specialist such as a urologist or orthopedic surgeon.

The procedure to untether the spinal cord creates scar tissue at the site which increases the risk for further tethering. There are a number of ways neurosurgeons try to avoid this, but it is a complicating factor that you and your neurosurgeon must take into consideration.

Meningocele

This is the rarest form of spina bifida. In this form of spina bifida called meningocele, the protective membranes around the spinal cord (meninges) push out through the opening in the vertebrae, forming a sac filled with fluid. But this sac doesn’t include the spinal cord, so nerve damage is less likely, but some babies may have problems controlling their bladder and bowels and later complications are possible. Surgery can remove the meningocele.

Figure 4. Meningocele

Spina bifida cystica

This is the most severe and the most common form of spina bifida and constitutes about 80% of the cases 9, 10. Myelomeningocele occurs in approximately 1 in 1200 to 1400 births 10. Spina bifida cystica also known as myelomeningocele or open spina bifida, is the most severe form of spina bifida and it refers to the meninges and spinal cord protruding through an opening in the baby’s back, forming a sac on the baby’s back. Part of the spinal cord and nerves are in this sac are damaged and has not developed properly. The spinal canal is open along several vertebrae in the lower or middle back. The membranes and spinal nerves push through this opening at birth, forming a sac on the baby’s back, typically exposing tissues and nerves. This makes the baby prone to life-threatening infections. Myelomeningocele type of spina bifida causes moderate to severe disabilities, such as problems affecting how the person goes to the bathroom, loss of sensation in the person’s legs or feet, and not being able to move the legs (paralysis or paraplegia). Babies with spina bifida cystica or myelomeningocele need surgery before birth or within the first few days of life. During surgery, a surgeon tucks the spinal cord and nerves back into the spine and covers them with muscle and skin. This can help prevent new nerve damage and infection. But the surgery can’t undo any damage that’s already happened. Even with surgery, babies with this condition have lasting disabilities, like problems walking and going to the bathroom.

Figure 5. Spina bifida cystica (Myelomeningocele)

Spina bifida Complications

Spina bifida may cause minimal symptoms or only minor physical disabilities. If the spina bifida is severe, sometimes it leads to more significant physical disabilities. Severity is affected by:

- The size and location of the neural tube defect

- Whether skin covers the affected area

- Which spinal nerves come out of the affected area of the spinal cord

This list of possible complications may seem overwhelming, but not all children with spina bifida get all these complications. Many of these complications can be treated.

- Walking and mobility problems. The nerves that control the leg muscles don’t work properly below the area of the spina bifida defect. This can cause muscle weakness of the legs and sometimes paralysis or paraplegia. Whether a child can walk typically depends on where the defect is, its size, and the care received before and after birth. Bracing using external orthosis can help to maximize their mobility and ensure a near-normal developmental progression. In children over 1-year-old, utilizing a standing frame can reduce the risk of osteoporosis and the formation of contractures in lower extremities. A wheelchair can provide mobility for older children and adults.

- Paralysis. People with spina bifida higher on the spine may have paralyzed legs or feet and need to use wheelchairs. Those with spina bifida lower on the spine (near the hips) may have more use of their legs. They may be able to walk on their own or use crutches, braces or walkers to help them walk. Some babies can start exercises for the legs and feet at an early age to help them walk with braces or crutches when they get older.

- Orthopedic complications. Children with myelomeningocele can have a variety of problems in the legs and spine because of weak muscles in the legs and back. The types of problems depend on the location of the defect. Possible problems include orthopedic issues such as:

- Curved spine (scoliosis)

- Abnormal growth

- Dislocation of the hip

- Bone and joint deformities

- Muscle contractures

- Bowel and bladder problems. Nerves that supply the bladder and bowels usually don’t work properly when children have myelomeningocele. This is because the nerves that supply the bowel and bladder come from the lowest level of the spinal cord.

- Most patients with myelomeningocele have some degree of bladder incontinence. Preventive goals are directed toward preventing infection with the implementation of bladder drainage utilizing intermittent catheterization or indwelling catheters. Bladder stimulation has shown to improve bladder emptying and reduce infection.

- Myelomeningocele is associated with anal sphincter dysfunction that results in bowel incontinence. Assisted bowel emptying reduces barriers associated with social activities, including attending school and personal relationships.

- Accumulation of fluid in the brain or hydrocephalus. Babies born with myelomeningocele commonly experience accumulation of fluid in the brain, a condition known as hydrocephalus. Extra fluid can cause the head to swell and put pressure on the brain. Hydrocephalus can cause intellectual and developmental disabilities. These are problems with how the brain works that can cause a person to have trouble or delays in physical development, learning, communicating, taking care of himself or getting along with others. In some cases, a surgeon needs to drain the extra fluid from a baby’s brain.

- Shunt malfunction.

- Shunt malfunction. Shunts placed in the brain to treat hydrocephalus can stop working or become infected. Warning signs may vary. Some of the warning signs of a shunt that isn’t working include:

- Headaches

- Vomiting

- Sleepiness

- Irritability

- Swelling or redness along the shunt

- Confusion

- Changes in the eyes (fixed downward gaze)

- Trouble feeding

- Seizures

- Chiari malformation type 2. Chiari malformation type 2 is a common problem with the brain in children who have the myelomeningocele type of spina bifida. The brainstem is the lowest part of the brain above the spinal cord. In Chiari malformation type 2, the brainstem is elongated and positioned lower than usual. This can cause problems with breathing and swallowing. Rarely, compression on this area of the brain occurs and surgery is needed to relieve the pressure.

- Infection in the tissues surrounding the brain (meningitis). Some babies with myelomeningocele may develop meningitis, an infection in the tissues surrounding the brain. This potentially life-threatening infection may cause brain injury.

- Shunt infections. Shunts are also prone to infections. When shunts are placed, infections can occur superficially at the skin or intraabdominal, as many of these patients have multiple abdominal procedures.

- Tethered spinal cord. Tethered spinal cord results when the spinal nerves bind to the scar where the defect was closed surgically, making the spinal cord less able to grow as the child grows. This progressive tethering can cause loss of muscle function to the legs, bowel or bladder. Surgery can limit the degree of disability.

- Sleep-disordered breathing. Both children and adults with spina bifida, particularly myelomeningocele, may have sleep apnea or other sleep disorders. Assessment for a sleep disorder in those with myelomeningocele helps detect sleep-disordered breathing, such as sleep apnea, which warrants treatment to improve health and quality of life.

- Skin problems. Children with spina bifida may get wounds on their feet, legs, buttocks or back. They can’t feel when they get a blister or sore. Sores or blisters can turn into deep wounds or foot infections that are hard to treat. Children with myelomeningocele have a higher risk of wound problems in casts.

- Latex allergy. Children with spina bifida have a higher risk of latex allergy, an allergic reaction to natural rubber or latex products. Latex allergy may cause rash, sneezing, itching, watery eyes and a runny nose. It can also cause anaphylaxis, a potentially life-threatening condition in which swelling of the face and airways can make breathing difficult. So it’s best to use latex-free gloves and equipment at delivery time and when caring for a child with spina bifida.

- Urinary tract infections (also called UTIs). The urinary tract is the system of organs (including the kidneys and bladder) that helps your body get rid of waste and extra fluids in the urine. Babies with spina bifida often can’t control when they go to the bathroom because the nerves that help a baby’s bladder and bowels work are damaged. If your baby has problems emptying the bladder completely, this can cause UTIs and kidney problems. Your baby’s health care provider can teach you how to use a plastic tube called a catheter to empty your baby’s bladder.

- Other complications. More problems may arise as children with spina bifida get older, such as urinary tract infections, gastrointestinal disorders and depression. Children with myelomeningocele may develop learning disorders, such as problems paying attention, and difficulty learning reading and math.

- Other conditions. Some people with spina bifida have problems with:

- Obesity (being very overweight)

- Digestion, the process of how your body breaks down food after you eat it

- Having sex

- Social and emotional conditions, including depression

- Vision.

Spina bifida life expectancy

There is no cure for spina bifida. The life expectancy of patients suffering from spina bifida depends on the size of the lesion. Patients with large complex defects have a shorter life expectancy. According to statistics, 40% to 50% of children with severe defects die as infants. Patients with higher and smaller lesions and no hydrocephalus have a longer life expectancy. Renal failure is the most common cause of death among these patients 10. The life expectancy of these patients has improved greatly with time owing to better healthcare services. However, most of these patients remain dependent on their parents and caretakers even in adulthood 10. Nowadays, the majority of patients with myelomeningocele have a near-normal life expectancy if they do not develop systemic complications.

The prognosis of spina bifida varies from case to case. It depends on many factors, such as the extent of neurological defect, presence of congenital malformations, time to treatment, and level of care. Usually, lower and less severe lesions have a better outcome as compared to higher lesions with hydrocephalus. Patients with lower and smaller lesions can be ambulatory. The majority of patients with myelomeningocele have normal intelligence, although 60% have some learning disabilities 10. Those with higher lesions tend to develop significant hydrocephalus and do not perform well academically. Most children with myelomeningocele require lifelong treatment focused on the damaged spinal cord and nerves. Children are usually followed closely with biannual clinic visits during childhood and annually during adulthood 10.

Spina bifida in adults

- Many adults living with Spina Bifida lead happy, productive and independent lives. There are just a few things that need attention.

- Find a good doctor that you can talk to. Link in to a Spina Bifida Service or Rehabilitation Specialist. The Spina Bifida Adult Resource team are a great resource in the community for people over 18. You can self-refer to them at Northcott. Try to have an annual review to stay ahead of any issues related to your Spina Bifida.

- Monitor your mobility. Be open to changing your mobility equipment to support your body, this may mean that you are able to be more independent for longer.

- See medical specialists urgently if you experience worsening spasms or loss of strength in legs or arms, and it is affecting your ability to walk or transfer.

- Check your skin but in particular your feet and bottom daily. Use a pressure cushion and wear shoes. If you develop pressure injuries or swelling on the legs see your doctor and follow up with your rehabilitation specialist. You should attend daily to self-skin checks and take good care with your hygiene. Use a podiatrist for managing your foot care.

- If you have orthoses remember to check them on a daily basis. They should be reviewed by an orthotist at least once a year. They need to be cleaned regularly & inspected for any signs of wear & tear. Although rare, sometimes the plastic or componentry of the orthoses may break and this could result in a fall. If ill fitting, they could contribute to pressure injury also.

- Have a renal ultrasound every year. Keep up your clean intermittent self-catheterisation program. You might require repeat urodynamic testing and a cystoscopy if you have had an indwelling catheter for more than 15 years. The frequency of testing will be decided by your treating urologist.

- Eat a balanced diet with sufficient fibre (eg. cereals, grain, fruit & vegetables). Remember that you will gain weight more easily so dietary advice may be necessary if you are gaining weight. Exercise regularly to maintain a healthy body weight.

- Ensure you have a regular shunt review by either a neurosurgeon or the Spina Bifida Service.

- Minimise alcohol consumption, recreational drugs and don’t smoke cigarettes.

- Know the reason why you are taking different medications and keep track of any changes.

- For women, be aware of the normal look and feel of your breast and see your doctor immediately if you notice any new or unusual changes.

- Women over 18 need second yearly pap smear and gynaecological review. Men need regular prostate cancer and related screening. It is important not to neglect aspects of your sexual health.

- Important general health reviews as you age include blood pressure and cholesterol checks, eye tests and blood sugar tests.

- It is important to have regular 6 monthly or 12 monthly dental reviews. In between dental visits good oral hygiene practices need to be maintained.

- Try to find social activities that you enjoy. Get out and about and have lots of fun.

Things to remember:

- Living well with Spina Bifida includes weight control, exercise, regular health and equipment reviews and vigilance to any warning symptoms.

- Know your body and be proactive in managing any changes.

- Make sure you tell new health care professionals about any allergies you may have.

- Use services and supports available to you to maintain your independence.

- Review your equipment on a daily basis. Remember to clean your equipment and keep up with maintenance needs.

Spina bifida causes

Scientists do not know all of the causes of spina bifida, however they believe that spina bifida is caused by a combination of genetic and environmental factors including the mother’s nutrition 11, 12, 13. Research has shown that getting enough folic acid (vitamin B9) or folate before and during pregnancy can prevent most cases of spina bifida 14.

If you are pregnant or planning to get pregnant, use the following tips to help prevent your baby from having spina bifida 14:

- Take 400 micrograms (mcg) of folic acid every day. If you have already had a pregnancy affected by spina bifida, you may need to take a higher dose of folic acid (folate) before pregnancy and during early pregnancy. Talk to your doctor to discuss what’s best for you.

- Talk to your doctor or pharmacist about any prescription and over-the-counter drugs, vitamins, and dietary or herbal supplements you are taking.

- If you have a medical condition―such as diabetes or obesity―be sure it is under control before you become pregnant.

- Avoid overheating your body, as might happen if you use a hot tub or sauna.

- Treat any fever you have right away with acetaminophen (paracetamol).

Spina bifida happens in the first few weeks of pregnancy during fetal development, at approximately 28 days (3-4 weeks) of gestation, often before a woman knows she’s pregnant 15, 5. Although folic acid (folate) is not a guarantee that a woman will have a healthy pregnancy, taking folic acid (folate) can help reduce a woman’s risk of having a pregnancy affected by spina bifida 14. Because half of all pregnancies in the United States are unplanned, it is important that all women who can become pregnant take 400 mcg of folic acid daily.

In cases of myelomeningocele, perinatal folic acid intake has shown to reduce the incidence of myelomeningocele significantly 13.

Other potential causes of spina bifida include genetic inheritance and racial backgrounds 13. Usually, infants who are born with spina bifida are born to mothers who have given birth to children with no history of spina bifida 13. However, after one child with spina bifida is born, the risk will increase to 1 in 20 for subsequent childbirth 13. Some infants born with spina bifida can have chromosomal anomalies such as as trisomies, duplications, deletions, and some single-gene mutations 16. Some reports show that pregestational diabetes increases the risk of central nervous system malformations, including spina bifida 10.

No specific individual factor has been identified to be related to open and closed spina bifida 10. Nutritional deficiency is the most common risk factor reported for any kind of spina bifida, causing up to 50% of all cases. In addition to folic acid deficiency, zinc deficiency is also found to be associated with spina bifida 13. Excessive intake of some elements can also lead to spina bifida. Vitamin A deficiency or excess can be associated with the formation of spina bifida 13. Moreover, nitrates are present in canned meat and groundwater and are known to cause spina bifida 13. Cytochalasin is a fungal metabolite, and its intake can also cause spina bifida in children 10. Some medications are also found to be associated with spina bifida. For example, sodium valproate, a well-known antiepileptic drug, is related to 1% to 2% chances of myelomeningocele formation when used in pregnancy 17, 18.

Risk factors for spina bifida

Spina bifida is more common among whites and Hispanics, and females are affected more often than males. Although doctors and researchers don’t know for sure why spina bifida occurs, they have identified some risk factors:

- Folate deficiency. Folate (vitamin B-9) is important to the healthy development of a baby. Folate is the natural form of vitamin B-9. The synthetic form, found in supplements and fortified foods, is called folic acid. A folate deficiency increases the risk of spina bifida and other neural tube defects. During pregnancy, take a prenatal vitamin each day that has 600 micrograms of folic acid in it.

- Family history of neural tube defects. Couples who’ve had one child with a neural tube defect have a slightly higher chance of having another baby with the same defect. That risk increases if two previous children have been affected by the condition. In addition, a woman who was born with a neural tube defect has a greater chance of giving birth to a child with spina bifida. However, most babies with spina bifida are born to parents with no known family history of the condition.

- You may be more likely than others to have a baby with spina bifida if:

- You or your partner has spina bifida. When one parent has spina bifida, there’s a 1 in 25 (4 percent) chance of passing spina bifida to your baby.

- You already have a child with spina bifida. In this case, there’s a 1 in 25 (4 percent) chance of having another baby with spina bifida.

- In these cases, you may want to see a genetic counselor. This is a person who is trained to help you understand how genes, birth defects and other medical conditions run in families, and how they can affect your health and your baby’s health. In most cases, spina bifida happens without any family history of the condition. This means no one in your family or your partner’s family has spina bifida.

- You may be more likely than others to have a baby with spina bifida if:

- Some medications. For example, anti-seizure medications, such as valproic acid (Depakene) and and carbamazepine, seem to cause neural tube defects when taken during pregnancy, possibly because they interfere with the body’s ability to use folate and folic acid. Doctors will try to avoid prescribing these medications if there’s a chance you could get pregnant while taking them, but they may be needed if the alternatives aren’t effective. It’s advisable to use a reliable form of contraception if you need to take one of these medications and aren’t trying to get pregnant. Tell your doctor if you’re thinking about trying for a baby and you need to take one of these medications. They may be able to lower the dose and prescribe folic acid supplements at a higher than normal dose, to reduce the risk of problems.

- Diabetes. Women with diabetes who don’t control their blood sugar well have a higher risk of having a baby with spina bifida.

- Obesity. Pre-pregnancy obesity is associated with an increased risk of neural tube birth defects, including spina bifida.

- Increased body temperature. Some evidence suggests that increased body temperature (hyperthermia) in the early weeks of pregnancy may increase the risk of spina bifida. Elevating your core body temperature, due to fever or the use of saunas or hot tubs, has been associated with a possible slight increased risk of spina bifida. If you have a fever, take acetaminophen (Tylenol®) right away and call your provider.

- Genetic conditions. Very rarely, spina bifida can occur alongside a genetic condition such as Patau’s syndrome, Edwards’ syndrome or Down’s syndrome. If your baby is found to have spina bifida and it’s thought they may also have one of these syndromes, you’ll be offered a diagnostic test, such as amniocentesis or chorionic villus sampling that can tell for certain if your baby has one of these genetic conditions.

If you have known risk factors for spina bifida, talk with your doctor to determine if you need a larger dose or prescription dose of folic acid, even before a pregnancy begins.

If you take medications, tell your doctor. Some medications can be adjusted to diminish the potential risk of spina bifida, if plans are made ahead of time.

Spina bifida prevention

Folic acid, taken in supplement form starting at least one month before conception and continuing through the first trimester of pregnancy, greatly reduces the risk of spina bifida and other neural tube defects.

Due to folic acid role in the synthesis of DNA and other critical cell components, folate is especially important during phases of rapid cell growth 19. Clear clinical trial evidence shows that when women take folic acid periconceptionally, a substantial proportion of neural tube defects is prevented 20. Scientists estimate that periconceptional folic acid use could reduce neural tube defects by 50% to 60% 21.

Since 1998, when the mandatory folic acid fortification program took effect in the United States, neural tube defect rates have declined by 25% to 30% 21. However, significant racial and ethnic disparities exist. Spina bifida and anencephaly rates have declined significantly among Hispanic and non-Hispanic white births in the United States, but not among non-Hispanic black births 22. Differences in dietary habits and supplement-taking practices could be a factor in these disparities 22. In addition, factors other than folate status—such as maternal diabetes, obesity, and intake of other nutrients such as vitamin B12—are believed to affect the risk of neural tube defects 23.

Because approximately 50% of pregnancies in the United States are unplanned, adequate folate status is especially important during the periconceptual period before a woman might be aware that she is pregnant. The Food and Nutrition Board at the Institute of Medicine advises women capable of becoming pregnant to “consume 400 mcg of folate daily from supplements, fortified foods, or both in addition to consuming food folate from a varied diet”24. The U.S. Public Health Service and the Centers for Disease Control and Prevention have published similar recommendations 25.

The Food and Nutrition Board at the Institute of Medicine has not issued recommendations for women who have had a previous neural tube defect and are planning to become pregnant again. However, other experts recommend that women obtain 4,000 to 5,000 mcg (4 – 5 mg) supplemental folic acid daily starting at least 1 to 3 months prior to conception and continuing for 2½ to 3 months after conception 26. These doses exceed the Tolerable Upper Intake Level (maximum daily intake unlikely to cause adverse health effects) and should be taken only under the supervision of a physician 27.

Get folic acid first

It’s critical to have enough folic acid in your system by the early weeks of pregnancy to prevent spina bifida. Because many women don’t discover that they’re pregnant until this time, experts recommend that all women of childbearing age take a daily supplement of folic acid. During pregnancy, demands for folate increase due to its role in nucleic acid synthesis 28. To accommodate this need, the Food and Nutrition Board at the Institute of Medicine increased the folate Recommended Dietary Allowance (RDA) from 400 mcg/day for nonpregnant women to 600 mcg/day during pregnancy 24. This level of intake might be difficult for many women to achieve through diet alone. The American College of Obstetricians and Gynecologists recommends a prenatal vitamin supplement for most pregnant women to ensure that they obtain adequate amounts of folic acid and other nutrients 29.

Folate is naturally present in many foods, and folic acid is added to some foods. You can get recommended amounts by eating a variety of foods, including the following.

- Folate is naturally present in:

- Beef liver

- Vegetables (especially asparagus, brussels sprouts, and dark green leafy vegetables such as spinach and mustard greens)

- Fruits and fruit juices (especially oranges and orange juice)

- Nuts, beans, and peas (such as peanuts, black-eyed peas, and kidney beans)

- Folic acid is added to the following foods:

- Enriched bread, flour, cornmeal, pasta, and rice

- Fortified breakfast cereals

- Fortified corn masa flour (used to make corn tortillas and tamales, for example)

To find out whether a food has added folic acid, look for “folic acid” on its Nutrition Facts label. Folic acid may be listed on food packages as folate, which is the natural form of folic acid found in foods.

Table 1. Folate and Folic Acid content of selected foods

| Food | Micrograms (mcg) DFE per serving | Percent DV* |

|---|---|---|

| Beef liver, braised, 3 ounces | 215 | 54 |

| Spinach, boiled, ½ cup | 131 | 33 |

| Black-eyed peas (cowpeas), boiled, ½ cup | 105 | 26 |

| Breakfast cereals, fortified with 25% of the DV† | 100 | 25 |

| Rice, white, medium-grain, cooked, ½ cup† | 90 | 22 |

| Asparagus, boiled, 4 spears | 89 | 22 |

| Brussels sprouts, frozen, boiled, ½ cup | 78 | 20 |

| Spaghetti, cooked, enriched, ½ cup† | 74 | 19 |

| Lettuce, romaine, shredded, 1 cup | 64 | 16 |

| Avocado, raw, sliced, ½ cup | 59 | 15 |

| Spinach, raw, 1 cup | 58 | 15 |

| Broccoli, chopped, frozen, cooked, ½ cup | 52 | 13 |

| Mustard greens, chopped, frozen, boiled, ½ cup | 52 | 13 |

| Bread, white, 1 slice† | 50 | 13 |

| Green peas, frozen, boiled, ½ cup | 47 | 12 |

| Kidney beans, canned, ½ cup | 46 | 12 |

| Wheat germ, 2 tablespoons | 40 | 10 |

| Tomato juice, canned, ¾ cup | 36 | 9 |

| Crab, Dungeness, 3 ounces | 36 | 9 |

| Orange juice, ¾ cup | 35 | 9 |

| Turnip greens, frozen, boiled, ½ cup | 32 | 8 |

| Peanuts, dry roasted, 1 ounce | 27 | 7 |

| Orange, fresh, 1 small | 29 | 7 |

| Papaya, raw, cubed, ½ cup | 27 | 7 |

| Banana, 1 medium | 24 | 6 |

| Yeast, baker’s, ¼ teaspoon | 23 | 6 |

| Egg, whole, hard-boiled, 1 large | 22 | 6 |

| Cantaloupe, raw, cubed, ½ cup | 17 | 4 |

| Vegetarian baked beans, canned, ½ cup | 15 | 4 |

| Fish, halibut, cooked, 3 ounces | 12 | 3 |

| Milk, 1% fat, 1 cup | 12 | 3 |

| Ground beef, 85% lean, cooked, 3 ounces | 7 | 2 |

| Chicken breast, roasted, 3 ounces | 3 | 1 |

Footnotes:

* DV = Daily Value. The FDA developed DVs (Daily Values) to help consumers compare the nutrient contents of foods and dietary supplements within the context of a total diet. The Daily Value for folate is 400 mcg DFE for adults and children aged 4 years and older 30, where mcg DFE = mcg naturally occurring folate + (1.7 x mcg folic acid). The labels must list folate content in mcg DFE per serving and if folic acid is added to the product, they must also list the amount of folic acid in mcg in parentheses. The FDA does not require food labels to list folate content unless folic acid has been added to the food. Foods providing 20% or more of the DV are considered to be high sources of a nutrient, but foods providing lower percentages of the DV also contribute to a healthful diet.

† Fortified with folic acid as part of the folate fortification program.

[Source 31 ]Planning pregnancy

If you’re actively trying to conceive, most pregnancy experts believe supplementation of at least 400 mcg of folic acid a day is the best approach for women planning pregnancy.

Your body doesn’t absorb folate as easily as it absorbs synthetic folic acid, and most people don’t get the recommended amount of folate through diet alone, so vitamin supplements are necessary to prevent spina bifida. And, it’s possible that folic acid will also help reduce the risk of other birth defects, including cleft lip, cleft palate and some congenital heart defects.

Folic acid is available in multivitamins and prenatal vitamins, supplements containing other B-complex vitamins, and supplements containing only folic acid. Common doses range from 680 to 1,360 mcg DFE (400 to 800 mcg folic acid) in supplements for adults and 340 to 680 mcg DFE (200 to 400 mcg folic acid) in children’s multivitamins 32.

About 85% of supplemental folic acid, when taken with food is bioavailable (that is around 85% of supplemental folic acid taken by mouth can be absorbed and used by the body) 33, 34. When consumed without food, nearly 100% of supplemental folic acid is bioavailable.

It’s also a good idea to eat a healthy diet, including foods rich in folate or enriched with folic acid. This vitamin is present naturally in many foods, including:

- Beans

- Citrus fruits and juices

- Egg yolks

- Dark green vegetables, such as broccoli and spinach

When higher folic acid doses are needed

If you have spina bifida or if you’ve given birth to a child with spina bifida, you’ll need extra folic acid before you become pregnant. If you’re taking anti-seizure medications or you have diabetes, you may also benefit from a higher dose of this B-9 vitamin. But check with your doctor before taking additional folic acid supplements.

Spina bifida symptoms

Signs and symptoms of spina bifida vary by type and severity. Symptoms can also differ for each person.

Spina bifida can cause a wide range of symptoms, including problems with movement, bladder and bowel problems, and problems associated with hydrocephalus (excess fluid on the brain).

The severity of the symptoms of spina bifida varies considerably, largely depending on the location of the gap in the spine.

A gap higher up the spine is more likely to cause paralysis of the legs and mobility difficulties compared with gaps in the middle or at the base of the spine, which may only cause continence issues.

A baby is more likely to have learning difficulties if they develop hydrocephalus.

- Spina bifida occulta. Because the spinal nerves usually aren’t involved, typically there are no signs or symptoms. But visible indications can sometimes be seen on the newborn’s skin above the spinal defect, including an abnormal tuft of hair, or a small dimple or birthmark.

- Meningocele. The membranes around the spinal cord push out through an opening in the vertebrae, forming a sac filled with fluid, but this sac doesn’t include the spinal cord.

- Myelomeningocele (spina bifida cystica). In this severe form of spina bifida:

- The spinal canal remains open along several vertebrae in the lower or middle back.

- Both the membranes and the spinal cord or nerves protrude at birth, forming a sac.

- Tissues and nerves usually are exposed, though sometimes skin covers the sac.

Spina bifida cystica (myelomeningocele) symptoms

Movement problems

The brain controls all the muscles in the body with the nerves that run through the spinal cord. Any damage to the nerves can result in problems controlling the muscles.

Most children with spina bifida have some degree of weakness or paralysis in their lower limbs. They may need to use ankle supports or crutches to help them move around. If they have severe paralysis, they’ll need a wheelchair.

Paralysis can also cause other, associated problems. For example, as the muscles in the legs aren’t being used regularly, they can become very weak.

As the muscles support the bones, muscle weakness can affect bone development. This can cause dislocated or deformed joints, bone fractures, misshapen bones and an abnormal curvature of the spine (scoliosis).

Bladder problems

Many people with spina bifida have problems storing and passing urine. This is caused by the nerves that control the bladder not forming properly. It can lead to problems such as:

- urinary incontinence

- urinary tract infections (UTIs)

- hydronephrosis – where one or both kidneys become stretched and swollen due to a build-up of urine inside them

- kidney scarring

- kidney stones

Due to the risk of infection, the bladder and kidneys will need to be regularly monitored. Ultrasound scans may be needed, as well as tests to measure the bladder’s volume and the pressure inside it.

Bowel problems

The nerves that run through the spinal cord also control the bowel and the sphincter muscles that keep stools in the bowel.

Many people with spina bifida have limited or no control over their sphincter muscles and have bowel incontinence.

Bowel incontinence often leads to periods of constipation followed by episodes of diarrhoea or soiling.

Hydrocephalus

Some babies with spina bifida have hydrocephalus (excess fluid on the brain), which can damage the brain and cause further problems.

Many people with spina bifida and hydrocephalus will have normal intelligence, although some will have learning difficulties, such as:

- a short attention span

- difficulty solving problems

- difficulty reading

- difficulty understanding some spoken language – particularly fast conversations between a group of people

- difficulty organising activities or making detailed plans

They may also have problems with visual and physical co-ordination – for example, tasks such as tying shoelaces or fastening buttons.

Some babies have a problem where the lower parts of the brain are pushed downwards towards the spinal cord. This is known as type 2 Arnold-Chiari malformation and is linked to hydrocephalus.

Hydrocephalus can cause additional symptoms soon after birth, such as irritability, seizures, drowsiness, vomiting and poor feeding.

Other problems

Other problems associated with spina bifida include:

- skin problems – reduced sensation can make it difficult to tell when the skin on the legs has been damaged – for example, if the skin gets burnt on a radiator; if a person with spina bifida injures their legs without realising, the skin could become infected or an ulcer could develop; it’s important to check the skin regularly for signs of injury

- latex allergy – people with spina bifida can develop an allergy to latex; symptoms can range from a mild allergic reaction – watery eyes and skin rashes – to a severe allergic reaction, known as anaphylactic shock, which requires an immediate injection of adrenalin; tell medical staff if you or your child is allergic to latex.

Spina bifida occulta signs and symptoms

Most people with spina bifida occulta do not even know they have it because the spinal nerves aren’t involved. But you can sometimes see signs on the newborn’s skin above the spinal problem, including a patch of hair, a small dimple or a birthmark or a red mark at the base of the spine. Sometimes, these skin marks can be signs of an underlying spinal cord issue that can be discovered with MRI or spinal ultrasound in a newborn.

Some people with spina bifida occulta also have a tethered cord. A tethered cord is a spinal cord that can’t move freely inside the spinal canal. Sometimes a tethered spinal cord needs to be released with surgery. Otherwise, it can stretch (especially during a growth spurt) and lead to pain, trouble walking, and loss of bladder (pee) control.

A tethered spinal cord may go undiagnosed until adulthood. Delayed presentation of symptoms can be insidious, meaning that symptoms come on slowly over time, but can be complex and severe. Back pain, brought on or worsened by activity and relieved with rest, can be a sign of spinal cord tethering.

Sometimes back pain is also associated with leg pain, even in areas that have decreased or no sensation. Changes in leg strength, deterioration in gait (walking), progressive or repeated muscle contractures, orthopedic deformities of the legs, scoliosis, and changes in bowel or bladder function may be signs of spinal cord tethering.

Meningocele signs and symptoms

Meningocele is when a sac made up of the meninges (the membranes that cover the brain and spinal cord) that contains spinal fluid pushes through the gap in the spine. The spinal cord is in its normal place in the spinal canal. The skin over the meningocele often is open. A meningocele can be seen on the baby’s head, neck, or back.

Most babies with a meningocele do not have any symptoms. Although it doesn’t happen very often, sometimes the nerves around the spine are damaged. This can lead to problems with movement and controlling when urine and poop comes out and other medical issues.

Spina bifida diagnosis

Spina bifida can be diagnosed during pregnancy or after your baby is born. Spina bifida occulta may not be diagnosed until late childhood or adulthood, or might never be diagnosed.

If you’re pregnant, you’ll be offered prenatal screening tests to check for spina bifida and other birth defects. The tests aren’t perfect. Some mothers who have positive blood tests have normal babies. Even if the results are negative, there’s still a small chance that spina bifida is present. Talk to your doctor about prenatal testing, its risks and how you might handle the results.

During pregnancy

During pregnancy there are screening tests (prenatal tests) to check for spina bifida and other birth defects, but typically the diagnosis is made with ultrasound. Talk with your doctor about any questions or concerns you have about this prenatal testing.

- Alpha-fetoprotein (AFP) – AFP (alpha-fetoprotein) is a protein the unborn baby produces. Maternal serum alpha-fetoprotein (MSAFP) test is a simple blood test that measures how much AFP has passed into the mother’s bloodstream from the baby. It’s normal for a small amount of AFP to cross the placenta and enter the mother’s bloodstream. But unusually high levels of AFP suggest that the baby has a neural tube defect, such as spina bifida, though high levels of AFP don’t always occur in spina bifida. An AFP test might be part of a test called the “triple screen” that looks for neural tube defects and other issues.

- Test to confirm high AFP levels. Varying levels of AFP can be caused by other factors — including a miscalculation in fetal age or multiple babies — so your doctor may order a follow-up blood test for confirmation. If the results are still high, you’ll need further evaluation, including an ultrasound exam.

- Other blood tests. Your doctor may perform the maternal serum alpha-fetoprotein (MSAFP) test with two or three other blood tests. These tests are commonly done with the MSAFP test, but their objective is to screen for other conditions, such as trisomy 21 (Down syndrome), not neural tube defects.

- Fetal ultrasound – An ultrasound is a type of picture of the baby. Fetal ultrasound is the most accurate method to diagnose spina bifida in your baby before delivery. In some cases, your doctor can see if the baby has spina bifida or find other reasons that there might be a high level of AFP. Frequently, spina bifida can be seen with ultrasound test. Ultrasound can be performed during the first trimester (11 to 14 weeks) and second trimester (18 to 22 weeks). Spina bifida can be accurately diagnosed during the second trimester ultrasound scan. Therefore, this examination is crucial to identify and rule out congenital anomalies such as spina bifida. An advanced ultrasound also can detect signs of spina bifida, such as an open spine or particular features in your baby’s brain that indicate spina bifida. In expert hands, ultrasound is also effective in assessing severity.

- Amniocentesis – If the prenatal ultrasound confirms the diagnosis of spina bifida, your doctor may request amniocentesis. For amniocentesis test, your doctor takes a small sample of the amniotic fluid surrounding the baby from the amniotic sac in the womb. Higher than average levels of AFP in the amniotic fluid might mean that your baby has spina bifida. Amniocentesis may be important to rule out genetic diseases, despite the fact that spina bifida is rarely associated with genetic diseases. Discuss the risks of amniocentesis, including a slight risk of loss of the pregnancy, with your doctor.

After your baby is born

In some cases, spina bifida might not be diagnosed until after your baby is born. Sometimes there is a hairy patch of skin or a dimple on the baby’s back that is first seen after the baby is born. A doctor can use an image scan, such as an, X-ray, MRI, or CT, to get a clearer view of the baby’s spine and the bones in the back.

- Computed tomography (also called CT or CAT scan). CT scans use special X-ray equipment and powerful computers to make pictures of the inside of your body.

- Magnetic resonance imaging (also called MRI). MRI is a medical test that makes a detailed picture of the inside of your body.

- X-ray. X-rays use radiation to make a picture of your baby’s body on film.

Sometimes spina bifida is not diagnosed until after the baby is born because the mother did not receive prenatal care or an ultrasound did not show clear pictures of the affected part of the spine.

Spina bifida treatment

Spina bifida treatment depends on the severity of the condition. Spina bifida occulta often doesn’t require treatment at all, but other types of spina bifida do.

If your child is diagnosed with spina bifida, they’ll be referred to a specialist team who will be involved in their care.

A care plan may be drawn up to address your child’s needs and any problems they have. As your child gets older, the care plan will be reassessed to take into account changes to their needs and situation.

There are several different treatments for the various problems spina bifida can cause. These are described below.

Surgery before birth

Sometimes when a baby has open spina bifida or myelomeningocele, doctors will perform surgery to close the spine before the baby is born. This surgery is a major procedure for the mother and the baby, and may not be available where you live. Contact a doctor who works regularly with spina bifida babies about the pros and cons of this option.

Nerve function in babies with spina bifida can worsen after birth if spina bifida isn’t treated. Prenatal surgery for spina bifida (fetal surgery) takes place before the 26th week of pregnancy. Surgeons expose the pregnant mother’s uterus surgically, open the uterus and repair the baby’s spinal cord. In select patients, this procedure can be performed less invasively with a special surgical tool (fetoscope) inserted into the uterus.

Research suggests that children with spina bifida who had fetal surgery may have reduced disability and be less likely to need crutches or other walking devices. Fetal surgery may also reduce the risk of hydrocephalus. Ask your doctor whether this procedure may be appropriate for you. Discuss the potential benefits and risks, such as possible premature delivery and other complications, for you and your baby.

It’s important to have a comprehensive evaluation to determine whether fetal surgery is feasible. This specialized surgery should only be done at a health care facility that has experienced fetal surgery experts, a multispecialty team approach and neonatal intensive care. Typically the team includes a fetal surgeon, pediatric neurosurgeon, maternal-fetal medicine specialist, fetal cardiologist and neonatologist.

Cesarean birth

Many babies with myelomeningocele tend to be in a feet-first (breech) position. If your baby is in this position or if your doctor has detected a large cyst or sac, cesarean birth may be a safer way to deliver your baby.

Surgery after birth

Meningocele involves surgery to put the meninges back in place and close the opening in the vertebrae. Because the spinal cord develops normally in babies with meningocele, these membranes often can be removed by surgery with little or no damage to nerve pathways.

Myelomeningocele also requires surgery to close the opening in the baby’s back within 72 hours of birth. Performing the surgery early can help minimize risk of infection that’s associated with the exposed nerves and may also help protect the spinal cord from more trauma.

During the procedure, a neurosurgeon places the spinal cord and exposed tissue inside the baby’s body and covers them with muscle and skin. Sometimes a shunt to control hydrocephalus in the baby’s brain is placed during the operation on the spinal cord.

Hydrocephalus

Many babies born with spina bifida get hydrocephalus (water on the brain). This means that there is extra cerebrospinal fluid (CSF) in and around the brain. The extra cerebrospinal fluid (CSF) can cause the spaces in the brain, called ventricles, to become too large and the head can swell. Hydrocephalus needs to be followed closely and treated properly to prevent brain injury.

If a baby with spina bifida has hydrocephalus, a neurosurgeon can put in a shunt. A shunt is a small hollow tube that will help drain excess cerebrospinal fluid (CSF) from the baby’s brain to another place where the body can remove it naturally and protect it from too much pressure. Additional surgery might be needed to change the shunt as the child grows up or if it becomes clogged or infected.

Shunts have valves that regulate both the direction and amount of fluid that is drained. Shunts have three parts:

- A ventricular catheter to reach the area where there is too much fluid

- A valve to control flow (there are many types)

- Tubing to carry the fluid from one place in the body to another.

The most common type of shunt is the ventriculo-peritoneal (VP) shunt. This shunt drains from the ventricle in the brain to the abdomen.

Most babies with myelomeningocele will need a surgically placed tube that allows fluid in the brain to drain into the abdomen (ventriculo-peritoneal (VP) shunt). This tube might be placed just after birth, during the surgery to close the sac on the lower back or later as fluid accumulates. A less invasive procedure, called endoscopic third ventriculostomy, may be an option. But candidates must be carefully chosen and meet certain criteria. During the procedure, the surgeon uses a small video camera to see inside the brain and makes a hole in the bottom of or between the ventricles so cerebrospinal fluid can flow out of the brain.

Other types of shunt that are less common are:

- Ventriculoatrial (VA) shunts—VA shunts move the to a vein, usually in the neck or under the collarbone

- Ventriculo-pleural shunts—These shunts move fluid to the chest around the lungs

- Ventriculo-gall bladder shunts—These shunts move to the gall bladder

There are several types of shunt valves. All of them work by controlling the amount of cerebrospinal fluid (CSF) that is drained. Most are made to work automatically when fluid pressure in the head gets too high. Some valves also may have special devices to keep too much fluid from draining. Experts have not yet learned which type of shunt is best for whom.

Neurosurgeons usually pick ones that they think are best. Shunts can be put into one of these places in the head:

- The edge of the soft spot

- Above and behind the ear

- The back of the head

Experts don’t know if one place is better than another. So where to put the shunt also is up to what the surgeon thinks is best. Almost all shunts are put in during the first days or weeks after birth. Sometimes the shunt will be inserted at the time of the initial back closure. A child who doesn’t need a shunt by the time they are 5 months old probably will never need one.

Signs of hydrocephalus or of shunt malfunction in infants

The signs of shunt problems in people with spina bifida are different for each person. This can make it hard for families and health care providers to know what’s going on. The most common sign of a shunt problem is a headache. Vomiting and nausea can happen, too, but not always.

Signs of hydrocephalus or of shunt malfunction in infants may include:

- Rapid head growth

- Full or tense soft spot (fontanelle)

- Unusual irritability

- Repeated vomiting

- Crossed eyes

- An inability to look up

- Periods in which the baby stops breathing (called apnea) swallowing

- A hoarse or weak cry in keeping the infant awake

- Any worsening brain function

Less common signs of a shunt problem include:

- Seizures (either the onset of new seizures or an increase in the frequency of existing seizures)

- A change in intellect, school performance or personality

- Back pain at the spine closure site

- Worsening arm or leg function (increasing weakness or loss of sensation, worsening coordination or balance and/ or worsening orthopedic deformities)

- Increasing scoliosis

- Worsening speech or swallowing

- Changes in bowel or bladder function

Shunt malfunction can look like any of the signs of a Chiari malformation or spinal cord tethering. When the brain or spinal cord function gets worse, and there is no other clear cause, health care providers should check to see if there are shunt problems.

A head ultrasound, computed tomography (CT) scan or a magnetic resonance imaging (MRI) scan will show cerebrospinal fluid (CSF) build-up, but a shunt still may not be working right even if it doesn’t show up on a CT or MRI scan.

To see if there is a problem with a shunt, doctors will study images of the brain (usually a CT scan or, for children under one year, a head ultrasound).

Most people with spina bifida and shunted hydrocephalus will need the shunt for life. The most common problem with shunts is that they can get blocked up, break or come apart. About 40 percent of shunts will fail and need changing or revision within one year, 60 percent within years and 80–85 percent within 10 years. About 20 percent of people with spina bifida will need more than one shunt revision.

New, long-term treatments using small endoscopes may eliminate the need for a shunt. All patients with hydrocephalus should be seen by a neurosurgeon at least every one to two years.

When ventricles start to get too big, it is a strong sign that the shunt is not working right. It is important to know that some people (between 5 and 15 percent) with spina bifida may have very few signs or even no visible change in the size of the ventricles when the shunt is not working correctly. On the other hand, some people with shunted hydrocephalus can develop the slit (or stiff) ventricle syndrome. For these people, too much fluid drainage leads to very small (or slit) ventricles. In these cases, experts think that the walls of the ventricles temporarily block the shunt catheter. This leads to a series of temporary shunt malfunctions without any visible increase in the size of the ventricles.

Families and health care providers must pay close attention to a person’s symptoms, especially if they are similar to those that were present with previous shunt problems.

Infections

Infection is a major problem that can happen with shunt operations. Between 5 and 10 percent of people will have this problem. Shunt infections are higher in babies than in older children and adults. Seventy percent of shunt infections happen within the first two months after a shunt operation. Eighty percent of these infections develop within the first six months. Skin bacteria (Staphylococcus epidermis) are the most common causes of shunt infection. Half of people with shunt infections show signs of a shunt malfunction. Additional signs of an infection include:

- Fever

- Neck stiffness

- Pain

- Tenderness

- Redness

- Drainage from the shunt incisions or tract

- Abdominal pain

The diagnosis can be checked by putting a small needle into the valve or a chamber of the shunt and taking out fluid for study. Infections are commonly treated with antibiotics and with removal and replacement of the shunt system. There are two ways of doing this. The first is to take out the shunt system and then put in a temporary external drainage tube at the same time that antibiotics are given. When the treatment is done, the tube is taken out, and a new shunt is put back in. This almost always stops the infection, but it takes two operations.

The second (assuming that the shunt is working) is to keep the infected shunt in until the end of the antibiotic treatment. Then the infected shunt is removed and replaced with a new one. The second way only takes one operation, but it does not get rid of the infection as often as the first.

Tethered spinal cord

Many people with open spina bifida have tethered spinal cords. A tethered spinal cord is attached to the spinal canal via surrounding structures. Normally, the bottom of the spinal cord floats around freely in the spinal canal, freely bending and stretching and moving up and down as the body grows. However, a tethered spinal cord does not move; it is pulled tightly at the end. This reduces blood flow to the spinal nerves and damages the spinal cord from the stretching and the decreased blood supply. Because the spinal cord stretches as a child grows, a tethered spinal cord can permanently damage the spinal nerves. Your child might have back pain, scoliosis (crooked spine), leg and foot weakness, changes in bladder or bowel control, and other problems. A tethered spinal cord can be treated with surgery.

A tethered spinal cord can happen before or after birth in children and adults with spina bífida, and most often occurs in the lower (lumbar) level of the spine 35. A tethered cord may go undiagnosed until adulthood when sometimes complex and severe symptoms come on slowly over time. While all forms of spina bifida can be accompanied by spinal cord tethering, it rarely occurs with occult spina bifida 35.

What is tethered spinal cord syndrome?

Tethered spinal cord syndrome is the presence of several clinically recognizable signs (observed by a physician), or symptoms (reported by the patient) that occur together as a result of spinal cord tethering. These signs and symptoms can include 35:

- sensory disturbance,

- significant muscle weakness (as determined by neurological assessment),

- pain, and

- urinary or bowel incontinence.

How does tethered spinal cord occur in myelomeningocele?

During the early stages of a pregnancy, the spinal cord of the fetus extends from the brain all the way down to the tailbone (coccygeal) region of the spine. As the pregnancy progresses, the bony spine grows faster than the spinal cord, so the end of the spinal cord appears to rise relative to the adjacent bony spine. By the time a child is born, the spinal cord is normally located opposite the disc between the first (L1) and second (L2) lumbar vertebrae, in the upper part of the lower back. In a baby with spina bifida, the spinal cord is still attached to the surrounding skin, and is prevented from ascending normally.

The spinal cord at birth is low-lying, or tethered. Although the myelomeningocele is surgically separated from the skin and closed at birth, the spinal cord, which has grown in this position, stays in roughly the same location after the closure, and quickly scars to the site. As the child and the bony spine continues to grow, the spinal cord can become stretched; damaging the spinal cord both by directly stretching it, and by interfering with the blood supply to the spinal cord. The result can be progressive neurological, urological, or orthopedic deterioration.

How does tethered spinal cord occur in milder forms of spina bifida?

Spinal cord tethering, usually in adults with milder forms of spina bifida may be related to the degree of strain placed on the spinal cord over time, and may appear or be significantly worsened during physical activity, injury, or pregnancy. It may also be caused by narrowing of the spinal column (spinal stenosis) or bony spurs.

A tethered spinal cord may go undiagnosed until adulthood. Delayed presentation of symptoms can be insidious, meaning that symptoms come on slowly over time, but can be complex and severe. Back pain, brought on or worsened by activity and relieved with rest, can be a sign of spinal cord tethering.

Sometimes back pain is also associated with leg pain, even in areas that have decreased or no sensation. Changes in leg strength, deterioration in gait (walking), progressive or repeated muscle contractures, orthopedic deformities of the legs, scoliosis, and changes in bowel or bladder function may be signs of spinal cord tethering.

How is a tethered spinal cord diagnosed?

If a child with myelomeningocele and shunted hydrocephalus presents with clinical worsening, the first issue is to determine whether or not the shunt is working, as shunt malfunction can appear the same as a tethered spinal cord. So, always check the shunt first 35. Accordingly, the first test is usually a computed tomography (CT) or magnetic resonance imaging (MRI) scan of the brain. Once the shunt is found to be working, or for those who do not have a shunt, an MRI of the spine is performed. It is important to know that virtually every child with spina bifida has evidence of tethering on the MRI. Untethering is therefore performed only if there are clinical signs or symptoms of deterioration.

The MRI is done to show the neurosurgeon the anatomy of the spinal cord tethering, and to exclude other abnormalities such as a syringomyelia (syrinx), split cord malformation, or a dermoid cyst (small tag of skin in the area around or within the spinal cord). Additional studies may include spine X-rays or CT scans of the spine to look for other bony abnormalities, or to follow the progress of scoliosis. Other functional studies

may be done, including Manual Muscle Testing (MMT) and urodynamics. Both are compared with previous studies to document changes, and to provide a pre-surgical baseline.

When is surgery performed?

After reviewing the diagnostic studies, the neurosurgeon may decide to untether the spinal cord. The decision to untether the spinal cord requires some clinical judgment. The neurosurgeon considers the patient’s symptoms, signs, and the results of the tests. Virtually every child with spina bifida has evidence of tethering on the MRI. Untethering the spinal cord is generally only done if there is clinical evidence of

deterioration, progressive or severe pain, loss of muscle function, deterioration in gait, or changes in bladder or bowel function. The longer deterioration continues, the less likely it is that function will return.

What happens after surgery?

Recovery in the hospital is generally about 2-5 days, and the patient often returns to normal activity within a few weeks 35. Some surgeons require the patient to remain at in bed for a couple of days to minimize the risk of spinal cerebrospinal fluid (CSF) leakage from the wound. Pain is often not severe, because there is usually some degree of numbness in that area anyway. Recovery of lost muscle and bladder function is variable, and depends on both the degree and length of the neurologic losses before the surgery.