What are mulberries

Mulberries (Morus alba L.), a member of the Moraceae family, comprises 10–16 species of deciduous trees, growing wild and under cultivation in many temperate world regions 1. Mulberry fruit is commonly eaten, often dried, or made into wine. In traditional oriental medicine, it has been used to treat premature grey hair, to nourish the blood, to treat constipation and diabetes and to generate body fluids, which generally means enhancing health and promoting longevity 2. In addition, mulberry has been reported to ameliorate inflammation-related haematological parameters in carrageenan-induced arthritic rats 3, to promote recovery from physical stress 4, to have neuroprotective effects against cerebral ischaemia 5 and to have radical-scavenging properties 6.

Like other berry fruits, mulberry fruit contains not only high amounts of anthocyanins 7, a subset of the flavonoids that are important natural antioxidants 8, but also non-anthocyanin phenolics including rutin and quercetin known to have multi-bioactive functions including neuroprotective effects 9. It may be assumed that these compounds have neuroprotective, antioxidant and anti-inflammatory effects in Parkinson’s disease models. However, few studies have actually examined the possible neuroprotective outcomes in experimental settings.

The fruit of the white mulberry – an East Asian species extensively naturalized in urban regions of eastern North America – has a different flavor, sometimes characterized as refreshing and a little tart, with a bit of gumminess to it and a hint of vanilla. In North America, the white mulberry is considered an invasive exotic and has taken over extensive tracts from native plant species, including the red mulberry 10.

The ripe fruit is edible and is widely used in pies, tarts, wines, cordials, and herbal teas. The fruit of the black mulberry (native to southwest Asia) and the red mulberry (native to eastern North America) have the strongest flavor, which has been likened to ‘fireworks in the mouth’.

The fruit and leaves are sold in various forms as nutritional supplements. The mature plant contains significant amounts of resveratrol, particularly in stem bark 11.

Mulberries vs Blackberries

Although blackberries might look similar in appearance, they are actually two separate type of aggregate fruits, composed of small drupelets. The blackberry is an edible fruit produced by many species in the Rubus genus in the Rosaceae family. Blackberry is widespread and well-known group of over 375 species, many of which are closely related apomictic microspecies native throughout Europe, northwestern Africa, temperate western and central Asia and North and South America 12. Blackberry fruits are red before they are ripe, leading to an old expression that “blackberries are red when they’re green”. On the other hand, the immature mulberry fruits are white, green, or pale yellow. In most species the mulberry fruits turn pink and then red while ripening, then dark purple or black, and have a sweet flavor when fully ripe. The fruits of the white-mulberry cultivar are white when ripe; the fruit of this cultivar is also sweet, but has a very bland flavor compared with darker mulberry varieties.

Blackberries are notable for their significant contents of dietary fiber, vitamin C and vitamin K (Table 2). A 100 gram serving of raw blackberries supplies 43 calories and 5 grams of dietary fiber or 25% of the recommended Daily Value (DV). In 100 grams, vitamin C and vitamin K contents are 25% and 19% DV, respectively, while other essential nutrients are low in content. For more differences, see Table 1. Mulberries and Table 2. Blackberries nutrition facts.

Blackberries contain both soluble and insoluble fiber components. Blackberries also contain numerous large seeds that are not always preferred by consumers. The seeds contain oil rich in omega-3 (alpha-linolenic acid) and -6 fats (linoleic acid) as well as protein, dietary fiber, carotenoids, ellagitannins and ellagic acid 13.

Figure 1. Mulberry

Figure 2. Blackberries

Mulberries nutrition facts

In a 100 g (3.5-oz) serving, raw mulberries provide 180 kJ (43 kcal), 44% of the Daily Value (DV) for vitamin C, and 14% of the DV for iron (Table 1). Other nutrients are in insignificant quantity.

Table 1. Mulberries nutrition facts

Nutrient | Unit | Value per 100 g | cup 140 g | fruit 15 g | |||||||||||||||

|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|

| Approximates | |||||||||||||||||||

| Water | g | 87.68 | 122.75 | 13.15 | |||||||||||||||

| Energy | kcal | 43 | 60 | 6 | |||||||||||||||

| Protein | g | 1.44 | 2.02 | 0.22 | |||||||||||||||

| Total lipid (fat) | g | 0.39 | 0.55 | 0.06 | |||||||||||||||

| Carbohydrate, by difference | g | 9.80 | 13.72 | 1.47 | |||||||||||||||

| Fiber, total dietary | g | 1.7 | 2.4 | 0.3 | |||||||||||||||

| Sugars, total | g | 8.10 | 11.34 | 1.22 | |||||||||||||||

| Minerals | |||||||||||||||||||

| Calcium, Ca | mg | 39 | 55 | 6 | |||||||||||||||

| Iron, Fe | mg | 1.85 | 2.59 | 0.28 | |||||||||||||||

| Magnesium, Mg | mg | 18 | 25 | 3 | |||||||||||||||

| Phosphorus, P | mg | 38 | 53 | 6 | |||||||||||||||

| Potassium, K | mg | 194 | 272 | 29 | |||||||||||||||

| Sodium, Na | mg | 10 | 14 | 2 | |||||||||||||||

| Zinc, Zn | mg | 0.12 | 0.17 | 0.02 | |||||||||||||||

| Vitamins | |||||||||||||||||||

| Vitamin C, total ascorbic acid | mg | 36.4 | 51.0 | 5.5 | |||||||||||||||

| Thiamin | mg | 0.029 | 0.041 | 0.004 | |||||||||||||||

| Riboflavin | mg | 0.101 | 0.141 | 0.015 | |||||||||||||||

| Niacin | mg | 0.620 | 0.868 | 0.093 | |||||||||||||||

| Vitamin B-6 | mg | 0.050 | 0.070 | 0.007 | |||||||||||||||

| Folate, DFE | µg | 6 | 8 | 1 | |||||||||||||||

| Vitamin B-12 | µg | 0.00 | 0.00 | 0.00 | |||||||||||||||

| Vitamin A, RAE | µg | 1 | 1 | 0 | |||||||||||||||

| Vitamin A, IU | IU | 25 | 35 | 4 | |||||||||||||||

| Vitamin E (alpha-tocopherol) | mg | 0.87 | 1.22 | 0.13 | |||||||||||||||

| Vitamin D (D2 + D3) | µg | 0.0 | 0.0 | 0.0 | |||||||||||||||

| Vitamin D | IU | 0 | 0 | 0 | |||||||||||||||

| Vitamin K (phylloquinone) | µg | 7.8 | 10.9 | 1.2 | |||||||||||||||

| Lipids | |||||||||||||||||||

| Fatty acids, total saturated | g | 0.027 | 0.038 | 0.004 | |||||||||||||||

| Fatty acids, total monounsaturated | g | 0.041 | 0.057 | 0.006 | |||||||||||||||

| Fatty acids, total polyunsaturated | g | 0.207 | 0.290 | 0.031 | |||||||||||||||

| Fatty acids, total trans | g | 0.000 | 0.000 | 0.000 | |||||||||||||||

| Cholesterol | mg | 0 | 0 | 0 | |||||||||||||||

| Other | |||||||||||||||||||

| Caffeine | mg | 0 | 0 | 0 | |||||||||||||||

Table 2. Blackberry nutrition facts

Nutrient | Unit | Value per 100 g | cup 144 g | ||||||||||||||||

|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|

| Approximates | |||||||||||||||||||

| Water | g | 88.15 | 126.94 | ||||||||||||||||

| Energy | kcal | 43 | 62 | ||||||||||||||||

| Protein | g | 1.39 | 2.00 | ||||||||||||||||

| Total lipid (fat) | g | 0.49 | 0.71 | ||||||||||||||||

| Carbohydrate, by difference | g | 9.61 | 13.84 | ||||||||||||||||

| Fiber, total dietary | g | 5.3 | 7.6 | ||||||||||||||||

| Sugars, total | g | 4.88 | 7.03 | ||||||||||||||||

| Minerals | |||||||||||||||||||

| Calcium, Ca | mg | 29 | 42 | ||||||||||||||||

| Iron, Fe | mg | 0.62 | 0.89 | ||||||||||||||||

| Magnesium, Mg | mg | 20 | 29 | ||||||||||||||||

| Phosphorus, P | mg | 22 | 32 | ||||||||||||||||

| Potassium, K | mg | 162 | 233 | ||||||||||||||||

| Sodium, Na | mg | 1 | 1 | ||||||||||||||||

| Zinc, Zn | mg | 0.53 | 0.76 | ||||||||||||||||

| Vitamins | |||||||||||||||||||

| Vitamin C, total ascorbic acid | mg | 21.0 | 30.2 | ||||||||||||||||

| Thiamin | mg | 0.020 | 0.029 | ||||||||||||||||

| Riboflavin | mg | 0.026 | 0.037 | ||||||||||||||||

| Niacin | mg | 0.646 | 0.930 | ||||||||||||||||

| Vitamin B-6 | mg | 0.030 | 0.043 | ||||||||||||||||

| Folate, DFE | µg | 25 | 36 | ||||||||||||||||

| Vitamin B-12 | µg | 0.00 | 0.00 | ||||||||||||||||

| Vitamin A, RAE | µg | 11 | 16 | ||||||||||||||||

| Vitamin A, IU | IU | 214 | 308 | ||||||||||||||||

| Vitamin E (alpha-tocopherol) | mg | 1.17 | 1.68 | ||||||||||||||||

| Vitamin D (D2 + D3) | µg | 0.0 | 0.0 | ||||||||||||||||

| Vitamin D | IU | 0 | 0 | ||||||||||||||||

| Vitamin K (phylloquinone) | µg | 19.8 | 28.5 | ||||||||||||||||

| Lipids | |||||||||||||||||||

| Fatty acids, total saturated | g | 0.014 | 0.020 | ||||||||||||||||

| Fatty acids, total monounsaturated | g | 0.047 | 0.068 | ||||||||||||||||

| Fatty acids, total polyunsaturated | g | 0.280 | 0.403 | ||||||||||||||||

| Fatty acids, total trans | g | 0.000 | 0.000 | ||||||||||||||||

| Cholesterol | mg | 0 | 0 | ||||||||||||||||

| Other | |||||||||||||||||||

| Caffeine | mg | 0 | 0 | ||||||||||||||||

Health benefits of mulberries

This study 15 showed the mulberry fruit extract, by its antioxidant and anti-apoptotic effects, significantly protected neurons against neurotoxins in test tube and in animal Parkinson’s disease models. These results suggest that mulberry fruit or compounds in it may provide neuroprotective candidates for use in treating or preventing Parkinson’s disease.

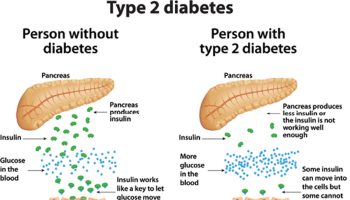

White mulberry (Morus alba) has been used over the centuries in traditional Chinese medicine as a common agent to treat a variety of conditions including diabetes, atherosclerosis, cancer as well as for boosting the immune system through potent antioxidant activity 16. Different parts of the mulberry plant (fruit, bark, leaf and root) have drawn interest in their role to treat diabetes, when the root and bark often was used to reduce hyperglycemia 17. Several studies have already investigated various alkaloids, flavonoids and phytochemicals in white mulberry, having found especially in leaves to exhibit anti-diabetic effects. These effects include inhibition of α-glycosidase, sucrase and maltase enzymes activity 18, 19, reducing carbohydrates metabolism and thus lowering blood glucose levels 18, prevention of lipid peroxidation 20, improvement of dyslipidemia, especially hypercholesterolemia 21 and inhibiting oxidation of LDL “bad” cholesterol 22. Kimura et al. 23 found 1-deoxynojirimycin, a reversible, competitive natural α-glucosidase inhibitor, an alkaloid in white mulberry leaf and reported to have non-fasting blood glucose lowering activity in humans 24. 1-deoxynojirimycin potently inhibits α-glucosidase in the small intestine by binding to the active center of α-glucosidase 25. More recently, 1-deoxynojirimycin has also been found in the leaves and fruits of mulberry 26, suggesting that the antidiabetic effect of mulberry leaves may be attributed to 1-deoxynojirimycin, which inhibits postprandial hyperglycemia 27 by inhibiting α-glucosidase in the small intestine. Nowadays, white mulberry leaf extracts are found in various food products especially sold as a tea and is readily available in many countries 21. However, contrary to many literature reports, this animal study on white mulberry leaf tea did not exhibit any hypoglycemic (anti-diabetic) effects. From the same study, white mulberry leaf tea did significantly lower serum total cholesterol and dose dependently lower serum LDL ‘bad”-cholesterol and triglycerides indicate the possible hypolipidemic effects of mulberry leaf tea 28. For the white mulberry leaf tea effects on blood cholesterol, Kojima et al. 29 tested the hypolipidemic effects of mulberry leaf extract in healthy non-diabetic human subjects and found no significant differences in serum total cholesterol, HDL “good” cholesterol and LDL “bad” cholesterols and triglyceride levels after 6 and 12 weeks.

Mulberry leaves are rich in 1-deoxynojirimycin, an inhibitor of α-glucosidase in the small intestine. Study 30 previously showed that 1-deoxynojirimycin-rich mulberry leaf extract suppressed elevation of postprandial blood glucose in humans. A study by Lown and colleagues 31 showed mulberry leaf extract significantly reduces total blood glucose rise after ingestion of maltodextrin over 120 minutes in 37 normoglycaemic adult subjects (aged 19–59 years with a BMI ≥ 20kg/m2 and ≤ 30kg/m2). Importantly, total insulin rises were also significantly suppressed over the same time-period. Furthermore, there were no statistically significant differences between any of the groups in experiencing one or more gastrointestinal symptoms (nausea, abdominal cramping, distension or flatulence).

In another randomized human trial 32 using mulberry leaf extract twenty four type 2 diabetic patents were divided randomly into two treatment groups: the mulberry leaf extract agent and glibenclamide (an antidiabetic drug), for 30 days. Serum and erythrocyte membrane lipid profiles of the patients were analyzed before and after the treatments. Results: Patients with mulberry therapy significantly improved their glycemic control vs. glibenclamide treatment. The results from pre- and post-treatment analysis of blood plasma and urine samples showed that the mulberry therapy significantly decreased the concentration of serum total cholesterol (12%), triglycerides “bad fat” (16%), plasma free fatty acids (12%), LDL “bad”-cholesterol (23%), VLDL-cholesterol (17%), plasma peroxides (25%), urinary peroxides (55%), while increasing HDL “good” cholesterol (18%). Although the patients with glibenclamide treatment showed marginal improvement in glycemic control, the changes in the lipid profile were not statistically significant except for triglycerides (10%), plasma peroxides (15%), and urinary peroxides (19%). Both treatments displayed no apparent effect on the concentrations of the glycosylated hemoglobin (Hb A1c) in diabetic patients. However, the fasting blood glucose concentrations of diabetic patients were significantly reduced by the mulberry therapy. Conclusions: Mulberry therapy exhibits potential hypoglycemic and hypolipidemic effects in diabetic patients 32.

References- http://www.fao.org/ag/AGP/AGPC/doc/Gbase/data/pf000542.htm

- JK Chen & TT Chen (2004) Tonic herbs. In Chinese Medical Herbology and Pharmacology, 1st ed., p. 959 [ L Crampton , editor]. City of Industry, CA: Art of Medicine Press.

- AJ Kim & S Park (2006) Mulberry extract supplements ameliorate the inflammation-related hematological parameters in carrageenan-induced arthritic rats. J Med Food 9, 431–435.

- KH Hwang (2004) Promoting effect and recovery activity from physical stress of the fruit of Morus alba. Biofactors 21, 267–271.

- TH Kang , JY Hur , HB Kim , et al. (2006) Neuroprotective effects of the cyanidin-3-O-β-d-glucopyranoside isolated from mulberry fruit against cerebral ischemia. Neurosci Lett 391, 122–126.

- M Isabelle , BL Lee , CN Ong , et al. (2008) Peroxyl radical scavenging capacity, polyphenolics, and lipophilic antioxidant profiles of mulberry fruits cultivated in Southern China. J Agric Food Chem 56, 9410–9416.

- PH Shih , YC Chan , JW Liao , et al. (2010) Antioxidant and cognitive promotion effects of anthocyanin-rich mulberry (Morus atropurpurea L.) on senescence-accelerated mice and prevention of Alzheimer’s disease. J Nutr Biochem (In the Press).

- RA Moyer , KE Hummer , CE Finn , et al. (2002) Anthocyanins, phenolics, and antioxidant capacity in diverse small fruits: vaccinium, rubus, and ribes. J Agric Food Chem 50, 519–525.

- W Zhang , F Han , J He , et al. (2008) HPLC-DAD-ESI–MS/MS analysis and antioxidant activities of nonanthocyanin phenolics in mulberry (Morus alba L.). J Food Chem 73, 512–518.

- Boning, Charles R. (2006). Florida’s Best Fruiting Plants: Native and Exotic Trees, Shrubs, and Vines. Sarasota, Florida: Pineapple Press, Inc. p. 153.

- [Study of anti-oxidant phenolic compounds from stem barks of Morus yunanensis]. Zhongguo Zhong Yao Za Zhi. 2008 Jul;33(13):1569-72. https://www.ncbi.nlm.nih.gov/pubmed/18837317

- Huxley, A., ed. (1992). New RHS Dictionary of Gardening. Macmillan. ISBN 0-333-47494-5.

- Bushman BS, Phillips B, Isbell T, Ou B, Crane JM, Knapp SJ (December 2004). “Chemical composition of caneberry (Rubus spp.) seeds and oils and their antioxidant potential”. Journal of Agricultural and Food Chemistry. 52 (26): 7982–7. https://www.ncbi.nlm.nih.gov/pubmed/15612785

- United States Department of Agriculture Agricultural Research Service. USDA Branded Food Products Database. https://ndb.nal.usda.gov/ndb/search/list

- Mulberry fruit protects dopaminergic neurons in toxin-induced Parkinson’s disease models. British Journal of Nutrition, Volume 104, Issue 1, 14 July 2010 , pp. 8-16.

- Butt M.S., Nazir A., Sultan M.T., SchroÎn K.: Trends Food Sci. Technol. 19, 505 (2008).

- Bantle J.P., Slama G.: Is fructose the optimal low glycemic index sweetener, in Nutritional Management of Diabetes Mellitus and Dysmetabolic Syndrome, pp. 83ñ89, Karger, Basel 2006.

- Oku T., Yamada M., Nakamura M., Sadamori N., Nakamura S.: Br. J. Nutr. 95, 933 (2006).

- Hansawasdi C., Kawabata J.: Fitoterapia 77, 568 (2006).

- Andallu B., Varadacjaryulu N.: Clin. Chim. Acta 338, 3 (2003).

- Kobayashi Y., Miyazawa M., Kamel A., Abe K., Kojima T.: Biosci. Biotechnol. Biochem. 74, 2385 (2010).

- Enkhmaa B., Shiwaku K., Katsube T., Kitajima K., Anuurad E. et al.: J. Nutr. 135, 729 (2005).

- Kimura T., Nakagawa K., Kubota H., Kojima Y., Goto Y. et al.: J. Agric. Food Chem. 55, 5869 (2007).

- Inhibitory effects of extractives from leaves of Morus alba on human and rat small intestinal disaccharidase activity. Oku T, Yamada M, Nakamura M, Sadamori N, Nakamura S. Br J Nutr. 2006 May; 95(5):933-8. https://www.ncbi.nlm.nih.gov/pubmed/16611383/

- Junge B., Matzke M., Stoltefuss J. Chemistry and structure-activity relationships of glucosidase inhibitors. in Handbook of Experimental Pharmacology, 119. Springer-Verlag; New York: 1996. pp. 411–482.

- Sugars with nitrogen in the ring isolated from the leaves of Morus bombycis. Asano N, Tomioka E, Kizu H, Matsui K. Carbohydr Res. 1994 Feb 3; 253():235-45. https://www.ncbi.nlm.nih.gov/pubmed/8156550/

- Polyhydroxylated alkaloids isolated from mulberry trees (Morusalba L.) and silkworms (Bombyx mori L.). Asano N, Yamashita T, Yasuda K, Ikeda K, Kizu H, Kameda Y, Kato A, Nash RJ, Lee HS, Ryu KS. J Agric Food Chem. 2001 Sep; 49(9):4208-13. https://www.ncbi.nlm.nih.gov/pubmed/11559112

- EFFECTS OF WHITE MULBERRY (MORUS ALBA) LEAF TEA INVESTIGATED IN A TYPE 2 DIABETES MODEL OF RATS. Acta Poloniae Pharmaceutica ñ Drug Research, Vol. 72 No. 1 pp. 153-160, 2015. http://www.ptfarm.pl/pub/File/Acta_Poloniae/2015/1/153.pdf

- Kojima Y., Kimura T., Nakagawa K., Asai A., Hasumi K. et al.: J. Clin. Biochem. Nutr. 47, 155 (2010).

- Kojima Y, Kimura T, Nakagawa K, et al. Effects of Mulberry Leaf Extract Rich in 1-Deoxynojirimycin on Blood Lipid Profiles in Humans. Journal of Clinical Biochemistry and Nutrition. 2010;47(2):155-161. doi:10.3164/jcbn.10-53. https://www.ncbi.nlm.nih.gov/pmc/articles/PMC2935155/

- Lown M, Fuller R, Lightowler H, et al. Mulberry-extract improves glucose tolerance and decreases insulin concentrations in normoglycaemic adults: Results of a randomised double-blind placebo-controlled study. Atkin SL, ed. PLoS ONE. 2017;12(2):e0172239. doi:10.1371/journal.pone.0172239. https://www.ncbi.nlm.nih.gov/pmc/articles/PMC5321430/

- Andallu B, Suryakantham V, Lakshmi B, Reddy GK. Effect of mulberry (Morus indica L.) therapy on plasma and erythrocyte membrane lipids in patients with type 2 diabetes. Clin Chim Acta. 2001. December;314(1–2):47–53. https://www.ncbi.nlm.nih.gov/pubmed/11718678