The Mayo Clinic Diet

The Mayo Clinic Diet is a long-term weight management program created by a team of weight-loss experts at Mayo Clinic 1. The Mayo Clinic Diet is designed to help you reshape your lifestyle by adopting healthy new habits and breaking unhealthy old ones. The goal is to make simple, pleasurable changes that will result in a healthy weight that you can maintain for the rest of your life.

The purpose of the Mayo Clinic Diet is to help you lose excess weight and to find a way of eating that you can sustain for a lifetime. It focuses on changing your daily routine by adding and breaking habits that can make a difference in your weight, such as eating more fruits and vegetables, not eating while you watch TV and moving your body for 30 minutes a day.

The Mayo Clinic Diet also stresses key components of behavior change, such as finding your inner motivation to lose weight, setting achievable goals and handling setbacks.

Why you might follow the Mayo Clinic Diet

You might choose to follow the Mayo Clinic Diet because you:

- Want to follow a diet that has been developed by medical professionals.

- Enjoy the types and amounts of food featured in the diet, including unlimited vegetables and fruits.

- Want to learn how to drop unhealthy lifestyle habits and gain healthy ones.

- Want to improve your health and reduce your health risks by becoming more active and eating the recommended foods.

- Don’t want to be precise about counting calories or grams of fat or eliminate entire groups of foods.

- Want a diet you can stick with for life, not a fad or quick fix

Diet details

The Mayo Clinic Diet is the official diet developed by Mayo Clinic, based on research and clinical experience. It focuses on eating healthy foods that taste great and increasing physical activity. It emphasizes that the best way to keep weight off for good is to change your lifestyle and adopt new health habits. This diet can be tailored to your own individual needs and health history — it isn’t a one-size-fits-all approach.

The Mayo Clinic Diet has two main parts:

- Lose It ! This two-week phase is designed to jump-start your weight loss, so you may lose up to 6 to 10 pounds (2.7 to 4.5 kilograms) in a safe and healthy way. In this phase, you focus on lifestyle habits that are associated with weight. You learn how to ADD 5 healthy habits, BREAK 5 unhealthy habits and ADOPT another 5 bonus healthy habits. This phase can help you see some quick results — a psychological boost — and start practicing important habits that you’ll carry into the next phase of the diet.

- Live It ! This phase is a lifelong approach to diet and health. In this phase, you learn more about food choices, portion sizes, menu planning, physical activity, exercise and sticking to healthy habits. You may continue to see a steady weight loss of 1 to 2 pounds (0.5 to 1 kilogram) a week until you reach your goal weight. This phase can also help you maintain your goal weight permanently.

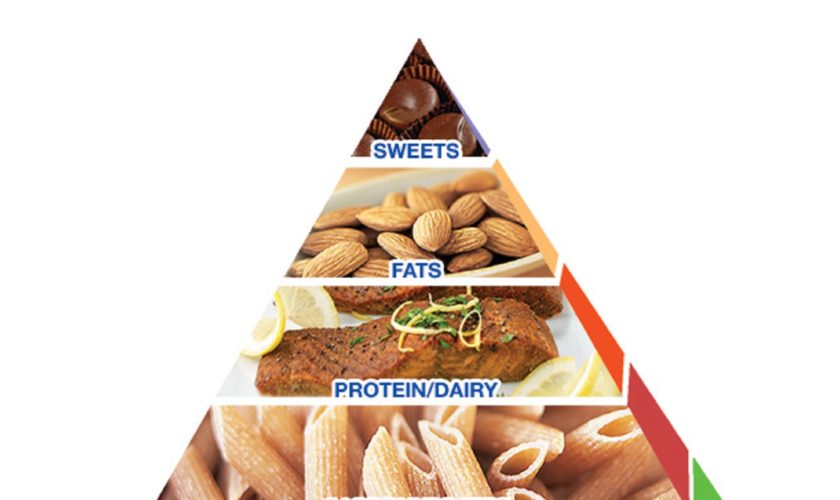

Follow the Mayo Clinic Healthy Weight Pyramid

The Mayo Clinic Healthy Weight Pyramid is a tool that helps guide you toward eating a balanced, nutritious diet while achieving a healthy weight.

The Mayo Clinic Diet doesn’t require you to be precise about counting calories or grams of fat. Instead, the Mayo Clinic Healthy Weight Pyramid serves as a guide to making smart eating choices. The main message is simple: Eat most of your food from the groups at the base of the pyramid and less from the top — and move more.

Vegetables and fruits, the foundation of the pyramid, should be your focus. These foods are low in energy density. That means you can eat a lot of them because they don’t contain a lot of calories. As you go up the pyramid, the food groups become higher in energy density — they have more calories for their volume. To lose weight, you should limit how many servings of these foods you eat.

The number of servings for each food group is determined by your daily target calorie level. If your target is 1,200 calories, your meal plan should include four or more servings of vegetables, three servings of protein/dairy and three fat servings.

Note: The Mayo Clinic Healthy Weight Pyramid

The Mayo Clinic Healthy Weight Pyramid is a tool to help you lose weight or maintain your weight. The triangular shape shows you where to focus when selecting healthy foods. Eat more foods from the base of the pyramid and fewer from the top.

Sample menu under the Mayo Clinic Healthy Weight Pyramid

This sample menu for a day follows the Mayo Clinic Healthy Weight Pyramid. The sample shows you how to fit in servings from each category in the pyramid without going over 1,200 calories. You can adjust the menu to suit your own tastes and calorie needs.

| Sample menu (1,200 calories) 1 |

|---|

| Breakfast |

| 3/4 cup hot whole-grain cereal |

| 1 small banana |

| Calorie-free beverage |

| Lunch |

| Tossed salad (2 cups romaine, 1/4 onion, 1/4 cup mushrooms, 1 medium tomato, 1 hard-boiled egg, 1/2 cup low-fat shredded cheddar cheese) |

| 1 whole-wheat dinner roll |

| 1 1/2 teaspoons butter |

| 1/2 cup cubed pineapple |

| Calorie-free beverage |

| Dinner |

| 3 ounces seared scallops in 1 teaspoon olive oil |

| Garlic mashed cauliflower potatoes |

| 1/2 cup beets |

| Calorie-free beverage |

| Snack (any time) |

| 2 plums |

| 8 wheat crackers |

| Nutritional analysis for sample menu | |

|---|---|

| Calories | 1,178 |

| Total fat | 34 g |

| Saturated fat | 12 g |

| Monounsaturated fat | 11 g |

| Cholesterol | 256 mg |

| Sodium | 1,761 mg |

| Total carbohydrate | 157 g |

| Dietary fiber | 24 g |

| Trans fat | Trace |

| Total sugar | 58 g |

| Added sugar | 0 g |

| Protein | 61 g |

| Mayo Clinic Healthy Weight Pyramid servings with the sample menu | |

|---|---|

| Vegetables | 4 |

| Fruits | 3 |

| Carbohydrates | 3 1/2 |

| Protein and dairy | 3 |

| Fats | 3 |

| Sweets | 0 |

Healthy snacking to help fill you up

If you feel hungry while following the Mayo Clinic Healthy Weight Pyramid, reach for more fruits and vegetables to snack on. Just make sure your fruit is either fresh or canned in water or juice — and that you pour off the liquid before eating.

Eat healthy foods and portions

The base of the Mayo Clinic Healthy Weight Pyramid focuses on generous amounts of healthy foods that contain a smaller number of calories in a large volume of food, particularly fruits and vegetables.

This principle involves eating low-energy-dense foods and can help you lose weight by feeling full on fewer calories. Healthy choices in each of the other food groups in moderate amounts make up the rest of the pyramid — including whole-grain carbohydrates, lean sources of protein such as legumes, fish and low-fat dairy, and heart-healthy unsaturated fats.

The Mayo Clinic Diet teaches you how to estimate portion sizes and plan meals. The diet doesn’t require you to eliminate any foods.

Increase your physical activity

The Mayo Clinic Diet provides practical and realistic ideas for including more physical activity and exercise throughout your day — as well as finding a plan that works for you. The diet recommends getting at least 30 minutes of exercise every day and even more exercise for further health benefits and weight loss. The diet also emphasizes moving more throughout the day, such as taking the stairs instead of an elevator.

Typical menu for the Mayo Clinic Diet Plan

The Mayo Clinic Diet provides several calorie levels. Here’s a look at a typical daily meal plan at the 1,200-calorie-a-day level:

- Breakfast: 1/2 cup cooked oatmeal with 1 cup milk and 2 tablespoons raisins, 1/4 cup mango, calorie-free beverage.

- Lunch: Quinoa and sweet potato cakes, tossed salad with fat-free dressing, calorie-free beverage.

- Dinner: 1 pita pizza, 3/4 cup mixed fruit, calorie-free beverage.

- Snack: 1 cup sliced bell peppers and 2 tablespoons hummus

You can have sweets — as long as you limit them to 75 calories a day. For practicality, consider thinking of your sweets calories over the course of a week. Have low-fat frozen yogurt or dark chocolate on Monday, and then hold off on any more sweets for a few days.

Before you begin The Mayo Clinic Diet, determine your starting point:

- Record your initial weight. Weigh yourself at a time and in a manner you’ll be able to use consistently, such as right after getting up in the morning.

- Determine your body mass index. BMI is a better indicator of body fat than is body weight. See the BMI table in the obesity article to determine your BMI. Write it down for future comparison.

- Measure your waist. Use a flexible tape and measure around your body just above the highest points on your hipbones. Record your result.

You’ll also want to:

- Consider your health. If you have health issues, such as diabetes, heart disease, shortness of breath or joint disease, are pregnant, or have any questions about your health, see your doctor before beginning this or any weight management program.

- Assess your readiness. There’s a good time to start losing weight, and there’s a bad time. You don’t want to put off your start date any longer than necessary, but you don’t want to set yourself up for failure either by starting at a time when you’re facing a lot of obstacles.

Results

- Weight loss

The Mayo Clinic Diet is designed to help you lose up to 6 to 10 pounds (2.7 to 4.5 kilograms) during the initial two-week phase. After that, you transition into the second phase, where you continue to lose 1 to 2 pounds (0.5 to 1 kilogram) a week until you reach your goal weight. By continuing the lifelong habits that you’ve learned, you can then maintain your goal weight for the rest of your life.

Most people can lose weight on almost any diet plan that restricts calories — at least in the short term. The goal of the Mayo Clinic Diet is to help you keep weight off permanently by making smarter food choices, learning how to manage setbacks and changing your lifestyle.

- Other health benefits

In general, losing weight by following a healthy, nutritious diet — such as the Mayo Clinic Diet — can reduce your risk of weight-related health problems, such as diabetes, heart disease, high blood pressure and sleep apnea. If you already have any of these conditions, they may be improved dramatically if you lose weight, regardless of the diet plan you follow.

In addition, the healthy habits and kinds of foods recommended on the Mayo Clinic Diet — including lots of vegetables, fruits, whole grains, nuts, beans, fish and healthy fats — can further reduce your risk of certain health conditions. The Mayo Clinic Diet is meant to be positive, active, sustainable and enjoyable, so you can enjoy a happier, healthier life over the long term.

Risks

The Mayo Clinic Diet is generally safe for most adults. It does encourage unlimited amounts of vegetables and fruits. For most people, eating lots of fruits and vegetables is a good thing. However, if you aren’t used to this, you may experience minor, temporary changes in digestion as your body adjusts to this new way of eating.

Also, the natural sugar in fruit does affect your carbohydrate intake — especially if you eat a lot of fruit. This may temporarily raise your blood sugar or certain blood fats. However, this effect is lessened if you are losing weight. If you have diabetes or any other health conditions or concerns, adjust the Mayo Clinic Diet for your situation. For example, people with diabetes should aim for more vegetables than fruits, if possible. It’s a good idea to snack on vegetables, rather than snacking only on fruit.