What is Protein

Proteins are large, complex molecules that play many critical roles in the body. They do most of the work in cells and are required for the structure, function, and regulation of the body’s tissues and organs. At least 10,000 different proteins make you what you are and keep you that way. Protein is in many foods that you eat. Protein can be found in foods from animals and from plants 1. Most diets include both types of protein — information available concerning the type of protein (e.g. animal or plant) to consume is limited.

Around the world, millions of people don’t get enough protein. Protein malnutrition leads to the condition known as kwashiorkor. Lack of protein can cause growth failure, loss of muscle mass, decreased immunity, weakening of the heart and respiratory system, and death 2.

Nutrients provided by various types of protein foods differ. For example, meats provide the most zinc, while poultry provides the most niacin. Meats, poultry, and seafood provide heme iron, which is more bioavailable than the non-heme iron found in plant sources. Heme iron is especially important for young children and women who are capable of becoming pregnant or who are pregnant. Seafood provides the most vitamin B12 and vitamin D, in addition to almost all of the polyunsaturated omega-3 fatty acids, eicosapentaenoic acid (EPA), and docosahexaenoic acid (DHA). Eggs provide the most choline, and nuts and seeds provide the most vitamin E. Soy products are a source of copper, manganese, and iron, as are legumes.

Protein provides the building blocks that help maintain and repair muscles, organs, and other parts of the body. Protein foods are important sources of nutrients in addition to protein, including B vitamins (e.g., niacin, vitamin B12, vitamin B6, and riboflavin), selenium, choline, phosphorus, zinc, copper, vitamin D, and vitamin E).

How Much Protein Do You Need at Meals?

Protein intake that exceeds the recommended daily allowance is widely accepted for both endurance and power athletes. However, considering the variety of proteins that are available much less is known concerning the benefits of consuming one protein versus another.

There are vastly different opinions on how much protein we actually need. Most official nutrition organizations recommend a fairly modest protein intake.

The Institute of Medicine recommends that adults get a minimum of 0.8 grams of protein for every kilogram of body weight per day (or 0.36 grams per pound of body weight) 3. The Recommended Dietary Allowance or Dietary Reference Intake is the amount of a nutrient you need to meet your basic nutritional requirements. In a sense, it’s the minimum amount you need to keep from getting sick — not the specific amount you are supposed to eat every day. The Institute of Medicine also sets a wide range for acceptable protein intake—anywhere from 10 to 35 percent of calories each day. Beyond that, there’s relatively little solid information on the ideal amount of protein in the diet or the healthiest target for calories contributed by protein.

This amounts to:

- 56-91 grams per day for the average sedentary man 4.

- 46-75 grams per day for the average sedentary woman 4.

For a relatively active adult, eating enough protein to meet the recommended dietary allowance would supply as little as 10% of his or her total daily calories. In comparison, the average American consumes around 16% of his or her daily calories in the form of protein, from both plant and animal sources.

Generally speaking, everyone has different needs when it comes to protein content at meal time. Depending on your weight, athletic practice, age, hormones, and lifestyle factors, you may need more than other people need. However, most meals shouldn’t contain less than 10 grams of protein per meal. Why ? Because this will provide balance to blood sugar levels, while also supplying amino acids to the neurotransmitters that help your nervous system function. Protein is also helpful for the digestive process, even in small amounts. It can give you sustained energy through the day by boosting metabolism. Ten grams, however, is a safe number that everyone can achieve without much thought. Then, if you’d like to add more (such as 15-20 grams per meal if you’re active), you can certainly do so. You should also aim to include 5-10 grams with each snack you eat to be sure you get enough and for the same nutritional benefits.

Proteins are made up of hundreds or thousands of smaller units called amino acids, which are attached to one another in long chains. There are 20 different types of amino acids that can be combined to make a protein. The sequence of amino acids determines each protein’s unique 3-dimensional structure and its specific function.

Proteins can be described according to their large range of functions in the body. Examples of protein functions:

- Antibody (e.g. Immunoglobulin G (IgG)): Antibodies bind to specific foreign particles, such as viruses and bacteria, to help protect the body.

- Enzyme (e.g. Phenylalanine hydroxylase): Enzymes carry out almost all of the thousands of chemical reactions that take place in cells. They also assist with the formation of new molecules by reading the genetic information stored in DNA.

- Messenger (e.g. Growth hormone): Messenger proteins, such as some types of hormones, transmit signals to coordinate biological processes between different cells, tissues, and organs.

- Structural component (e.g. Actin): These proteins provide structure and support for cells. On a larger scale, they also allow the body to move.

- Transport/storage (e.g. Ferritin): These proteins bind and carry atoms and small molecules within cells and throughout the body.

Role of Protein

Proteins are nitrogen-containing substances that are formed by amino acids. They serve as the major structural component of muscle and other tissues in the body. In addition, they are used to produce hormones, enzymes and hemoglobin. Proteins can also be used as energy; however, they are not the primary choice as an energy source. For proteins to be used by the body they need to be metabolized into their simplest form, amino acids. There have been 20 amino acids identified that are needed for human growth and metabolism. Twelve of these amino acids (eleven in children) are termed nonessential, meaning that they can be synthesized by our body and do not need to be consumed in the diet. The remaining amino acids cannot be synthesized in the body and are described as essential meaning that they need to be consumed in our diets. The absence of any of these amino acids will compromise the ability of tissue to grow, be repaired or be maintained.

Proteins are made up of hundreds or thousands of smaller units called amino acids, which are attached to one another in long chains. There are 20 different types of amino acids that can be combined to make a protein. The sequence of amino acids determines each protein’s unique 3-dimensional structure and its specific function.

Proteins can be described according to their large range of functions in the body, listed in alphabetical order:

Examples of protein functions

| Function | Description | Example |

|---|---|---|

| Antibody | Antibodies bind to specific foreign particles, such as viruses and bacteria, to help protect the body. | Immunoglobulin G (IgG) |

| Enzyme | Enzymes carry out almost all of the thousands of chemical reactions that take place in cells. They also assist with the formation of new molecules by reading the genetic information stored in DNA. | Phenylalanine hydroxylase |

| Messenger | Messenger proteins, such as some types of hormones, transmit signals to coordinate biological processes between different cells, tissues, and organs. | Growth hormone |

| Structural component | These proteins provide structure and support for cells. On a larger scale, they also allow the body to move. | Actin |

| Transport/storage | These proteins bind and carry atoms and small molecules within cells and throughout the body. | Ferritin |

What to look for to tell if you’re lacking in protein

Look for the following signs if you’re worried about protein deficiency:

- Anxiety/depression (amino acids fuel the neurotransmitters serotonin and dopamine that prevent depression and anxiety)

- Poor injury recovery (protein fuels muscle recovery and regrowth)

- Hair Loss/Breakage (protein supports collagen production in the hair, skin, and nails)

- Inability to focus (amino acids support brain performance)

- Constant muscle pain (protein helps muscle recovery and aids in repair)

- Brittle/Breaking Nails (protein supports collagen production in the hair, skin, and nails)

- Poor muscle tone, even with exercise (protein builds and maintains lean muscle mass)

- Constantly fatigued (protein is needed for a healthy metabolism)

- Digestive issues (protein aids in digestion)

It’s important to note that a diet too low in calories or too high in sugar will also cause these symptoms too, so eliminate those causes before you add more protein.

What are Amino Acids?

Amino acids are organic compounds that combine to form proteins 6. Amino acids and proteins are the building blocks of life that help maintain and repair muscles, organs, and other parts of the body.

Animal protein includes all of the building blocks that your body needs. Plant proteins need to be combined to get all of the building blocks that your body needs.

In the human body, certain amino acids can be converted to other amino acids, proteins, glucose, fatty acids or ketones. For example, in the human body, glucogenic amino acids can be converted to glucose in the process called gluconeogenesis; they include all amino acids except lysine and leucine 7, 8.

Ketogenic amino acids, are amino acids that can be converted into ketone bodies through ketogenesis. In humans, the ketogenic amino acids are leucine and lysine, while threonine, isoleucine, phenylalanine, tyrosine and tryptophan can be either ketogenic or glucogenic 9. Ketones can be used by the brain as a source of energy during fasting or in a low-carbohydrate diet.

When proteins are digested or broken down, amino acids are left.

The human body uses amino acids to make proteins to help the body:

- Break down food

- Grow

- Repair body tissue

- Perform many other body functions

- Amino acids can also be used as a source of energy by the body, like proteins, they can provide about 4 Calories per gram.

Other functions of amino acids:

- Chemical messengers (neurotransmitters) in the nervous system: aspartate, GABA, glutamate, glycine, serine

- Precursors of other neurotransmitters or amino acid-based hormones:

- Tyrosine is a precursor of dopamine, epinephrine, norepinephrine and thyroxine.

- Tryptophan is a precursor of melatonin and serotonin and nicotinic acid (vitamin B3).

- Histidine is a precursor of histamine.

- Glycine is a precursor of heme, a part of hemoglobin.

- Aspartate, glutamate and glycine are precursors of nucleic acids, which are parts of DNA.

Amino acids are classified into three groups:

- Essential amino acids.

- Nonessential amino acids.

- Conditional amino acids.

You do not need to eat essential and nonessential amino acids at every meal, but getting a balance of them over the whole day is important. A diet based on a single plant item will not be adequate, but we no longer worry about pairing proteins (such as beans with rice) at a single meal. Instead we look at the adequacy of the diet overall throughout the day.

Essential Amino Acids

The 9 amino acids are essential (vital), which means they are necessary for the human life and health but cannot be produced in your body so you need to get them from foods 10.

- Histidine (His)

- Isoleucine (Ile)

- Leucine (Leu)

- Lysine (Lys)

- Methionine (Met)

- Phenylalanine (Phe)

- Threonine (Thr)

- Tryptophan (Trp)

- Valine (Val).

Conditionally Essential Amino Acids

These amino acids can be synthesized in your body, but in certain circumstances, like young age, illness or hard exercise, you need to get them in additional amounts from foods to meet the body requirements for them. Ornithine is also considered conditionally essential amino acid, but it does not form proteins 6.

- Arginine (Arg)

- Cysteine (Cys)

- Glutamine (Gln)

- Glycine (Gly)

- Proline (Pro)

- Serine (Ser)

- Tyrosine (Tyr)

Nonessential Amino Acids

These amino acids can be synthesized in your body from other amino acids, glucose and fatty acids, so you do not need to get them from foods.

- Alanine (Ala)

- Asparagine (Asn)

- Aspartic acid (Asp)

- Glutamic acid (Glu)

- Selenocysteine (Sec).

Protein Sources

Foods that Contain All 9 Essential Amino Acids

Food protein containing all 9 amino acids in adequate amounts is called complete or high-quality protein.

- ANIMAL FOODS with complete protein include liver (chicken, pork, beef), goose, duck, turkey, chicken, lamb, pork, most fish, rabbit, eggs, milk, cheese (cottage, gjetost, cream, swiss, ricotta, limburger, gruyere, gouda, fontina, edam) and certain beef cuts. Animal foods with incomplete protein include certain yogurts and beef cuts.

- PLANT FOODS with complete protein include spinach, beans (black, cranberry, french, pink, white, winged, yellow), soy, split peas, chickpeas, chestnuts, pistachios, pumpkin seeds, avocado, potatoes, quinoa, a seaweed spirulina, tofu and hummus. Common plant foods with incomplete protein: rice (white and brown), white bread (including whole-wheat), pasta, beans (adzuki, baked, kidney, lima, pinto, snap), peas, lentils, nuts (walnuts, peanuts, hazelnuts, almonds, coconut), sunflower seeds, kamut.

- Foods made of mycoprotein also contain complete protein.

All protein isn’t alike. Protein is built from building blocks called amino acids. Our bodies make amino acids in two different ways: Either from scratch, or by modifying others. A few amino acids (known as the essential amino acids) must come from food.

Protein is available in a variety of dietary sources. These include foods of animal and plant origins as well as the highly marketed sport supplement industry. In determining the effectiveness of a protein is accomplished by determining its quality and digestibility. Quality refers to the availability of amino acids that it supplies, and digestibility considers how the protein is best utilized. Typically, all dietary animal protein sources are considered to be complete proteins. That is, a protein that contains all of the essential amino acids 11. Proteins from vegetable sources are incomplete in that they are generally lacking one or two essential amino acids. Thus, someone who desires to get their protein from vegetable sources (i.e. vegetarian, vegan) will need to consume a variety of vegetables, fruits, grains, and legumes to ensure consumption of all essential amino acids. As such, individuals are able to achieve necessary protein requirements without consuming beef, poultry, or dairy 11. Protein digestibility ratings usually involve measuring how the body can efficiently utilize dietary sources of protein. Typically, vegetable protein sources do not score as high in ratings of biological value, net protein utilization, protein digestibility corrected amino acid score and protein efficiency ratio as animal proteins.

Vegetarians need to be aware of this. People who don’t eat meat, fish, poultry, eggs, or dairy products need to eat a variety of protein-containing foods each day in order to get all the amino acids needed to make new protein.

- Animal Protein Foods : Animal sources of protein tend to deliver all the amino acids we need. Meat, such as pork, beef, chicken, turkey, duck / Eggs / Dairy products, such as milk, yogurt, cheese / Fish

- Plant (Vegetable) Protein Foods : Other protein sources, such as fruits, vegetables, grains, nuts and seeds, lack one or more essential amino acids.

- High Protein Plant Foods: Beans, peas, lentils / Soy foods, such as soy milk, tofu / Nuts and nut spreads, such as almond butter, pea

/ nut butter, soy nut butter /Sunflower seeds 1 - Low Protein Plant Foods: Bread, tortillas / Oatmeal, grits, cereals / Pasta, noodles, rice / Rice milk (not enriched).

Animal Protein

Proteins from animal sources (i.e. eggs, milk, meat, fish and poultry) provide the highest quality rating of food sources 11. This is primarily due to the ‘completeness’ of proteins from these sources. Animal protein includes all of the building blocks that your body needs. Protein from animal sources during late pregnancy is believed to have an important role in infants born with normal body weights. A low intake of protein from dairy and meat sources during late pregnancy was associated with low birth weights.

In addition to the benefits from total protein consumption, elderly subjects have also benefited from consuming animal sources of protein. Diets consisting of meat resulted in greater gains in lean body mass compared to subjects on a lacto-ovo-vegetarian diet 12. High animal protein diets have also been shown to cause a significantly greater net protein synthesis than a high vegetable protein diet 13. This was suggested to be a function of reduced protein breakdown occurring during the high animal protein diet.

There have been a number of health concerns raised concerning the risks associated with protein emanating primarily from animal sources. Primarily, these health risks have focused on cardiovascular disease (due to the high saturated fat and cholesterol consumption), bone health (from bone resorption due to sulfur-containing amino acids associated with animal protein) and other physiological system disease that will be addressed in the section on the high protein diets.

1. Whey: Whey is a general term that typically denotes the translucent liquid part of milk that remains following the process (coagulation and curd removal) of cheese manufacturing. From this liquid, whey proteins are separated and purified using various techniques yielding different concentrations of whey proteins. There are three main forms of whey protein that result from various processing techniques used to separate whey protein. They are whey powder, whey concentrate, and whey isolate 11.

Whey is one of the two major protein groups of bovine milk, accounting for 20% of the milk while casein accounts for the remainder. All of the constituents of whey protein provide high levels of the essential and branched chain amino acids. The bioactivities of these proteins possess many beneficial properties as well. Additionally, whey is also rich in vitamins and minerals. Whey protein is most recognized for its applicability in sports nutrition. Additionally, whey products are also evident in baked goods, salad dressings, emulsifiers, infant formulas, and medical nutritional formulas.

Whey is a complete protein whose biologically active components provide additional benefits to enhance human function. Whey protein contains an ample supply of the amino acid cysteine. Cysteine appears to enhance glutathione levels, which has been shown to have strong antioxidant properties that can assist the body in combating various diseases 14. In addition, whey protein contains a number of other proteins that positively effect immune function such as antimicrobial activity 15. Whey protein also contains a high concentration of branched chain amino acids (BCAA) that are important for their role in the maintenance of tissue and prevention of catabolic actions during exercise 16.

- Whey Protein Powder

Whey protein powder has many applications throughout the food industry. As an additive it is seen in food products for beef, dairy, bakery, confectionery, and snack products. Whey powder itself has several different varieties including sweet whey, acid whey (seen in salad dressings), demineralized (seen primarily as a food additive including infant formulas), and reduced forms. The demineralized and reduced forms are used in products other than sports supplements.

- Whey Protein Concentrate

The processing of whey concentrate removes the water, lactose, ash, and some minerals. In addition, compared to whey isolates whey concentrate typically contains more biologically active components and proteins that make them a very attractive supplement for the athlete.

- Whey Protein Isolate (WPI)

Isolates are the purest protein source available. Whey protein isolates contain protein concentrations of 90% or higher. During the processing of whey protein isolate there is a significant removal of fat and lactose. As a result, individuals who are lactose-intolerant can often safely take these products 17. Although the concentration of protein in this form of whey protein is the highest, it often contain proteins that have become denatured due to the manufacturing process. The denaturation of proteins involves breaking down their structure and losing peptide bonds and reducing the effectiveness of the protein.

2. Casein: Casein is the major component of protein found in cow (bovine) milk accounting for nearly 70-80% of its total protein and is responsible for the white color of milk 11. It is the most commonly used milk protein in the industry today. Milk proteins are of significant physiological importance to the body for functions relating to the uptake of nutrients and vitamins and they are a source of biologically active peptides. Similar to whey, casein is a complete protein and also contains the minerals calcium and phosphorous. Casein has a PDCAAS (protein digestibility corrected amino acid score) rating of 1.23 (generally reported as a truncated value of 1.0) 18.

Casein exists in milk in the form of a micelle, which is a large colloidal particle. An attractive property of the casein micelle is its ability to form a gel or clot in the stomach. The ability to form this clot makes it very efficient in nutrient supply. The clot is able to provide a sustained slow release of amino acids into the blood stream, sometimes lasting for several hours 19. This provides better nitrogen retention and utilization by the body.

3. Bovine Colostrum: Bovine colostrum is the “pre” milk liquid secreted by female mammals the first few days following birth. This nutrient-dense fluid is important for the newborn for its ability to provide immunities and assist in the growth of developing tissues in the initial stages of life. Evidence exists that bovine colostrum contains growth factors that stimulate cellular growth and DNA synthesis 20 and as might be expected with such properties, it makes for interesting choice as a potential sports supplement.

Although bovine colostrum is not typically thought of as a food supplement, the use by strength/power athletes of this protein supplement as an ergogenic aid has become common. Oral supplementation of bovine colostrum has been demonstrated to significantly elevate insulin-like-growth factor 1 (IGF-1) 21 and enhance lean tissue accruement 22, 23. However, the results on athletic performance improvement are less conclusive. Mero and colleagues (1997) reported no changes in vertical jump performance following 2-weeks of supplementation, and Brinkworth and colleagues 23 saw no significant differences in strength following 8-weeks of training and supplementation in both trained and untrained subjects. In contrast, following 8-weeks of supplementation significant improvements in sprint performance were seen in elite hockey players 24. Further research concerning bovine colostrum supplementation is still warranted.

Non-meat Protein Sources

The Healthy Eating Plate suggests filling half your plate with vegetables and fruits as part of an optimal diet, but planning your meals around vegetables and fruits produce benefits the planet as well. Shifting to a more plant-based way of eating will help reduce freshwater withdrawals and deforestation 25 —a win-win for both your personal health and the environment. Meat production is a substantial contributor to greenhouse gas emissions – beef production especially – and the environmental burden deepens, as raising and transporting livestock also requires more food, water, land, and energy than plants 26. To eat for your own health as well as that of the planet, you should consider picking non-meat proteins such as nuts and legumes.

- For recipes you may want to visit The Vegetarian Society Recipes 27

Plant/vegetable based proteins need to be combined to get all of the essential amino acids that your body needs. Vegetable proteins provide an excellent source for protein considering that they will likely result in a reduction in the intake of saturated fat and cholesterol. Popular sources include legumes, nuts and soy. Aside from these products, vegetable protein can also be found in a fibrous form called textured vegetable protein. Textured vegetable protein is produced from soy flour in which proteins are isolated. Textured vegetable protein is mainly a meat alternative and functions as a meat analog in vegetarian hot dogs, hamburgers, chicken patties, etc. It is also a low-calorie and low-fat source of vegetable protein. Vegetable sources of protein also provide numerous other nutrients such as phytochemicals, vitamins, iron and fiber that are also highly regarded in the diet.

However, the problem with the view of protein is where you are getting the majority of your protein from: animals.

Regardless of different opinions out there about including meat as a part of your regular diets, you can’t ignore the fact that meat consumption is causing major environmental, health, and humanitarian problems. When you put all the pieces together, it is time to start looking for a real sustainable alternative.

1. Soy

Soy is the most widely used vegetable protein source. The soybean, from the legume family, was first chronicled in China in the year 2838 B.C. and was considered to be as valuable as wheat, barley, and rice as a nutritional staple. It is found in modern American diets as a food or food additive 28. Soybeans, the high-protein seeds of the soy plant, contain isoflavones—compounds similar to the female hormone estrogen (phytoestrogens). Isoflavones are often referred to as phytoestrogens or plant-based estrogens because they have been shown, in cell line and animal studies, to have the ability to bind with the estrogen receptor 29. Research alos suggests that daily intake of soy protein may slightly lower levels of LDL (“bad”) cholesterol. Soy products are used for menopausal symptoms, bone health, improving memory, high blood pressure, and high cholesterol levels 28. In addition to its food uses, soy is available in dietary supplements, in forms such as tablets, capsules, and powders. Soy supplements may contain soy protein, isoflavones (compounds that have effects in the body similar to those of the female hormone estrogen), or other soy components 28.

Soy protein is a high quality protein that has been extensively studied. Soy provides a complete source of dietary protein, meaning that, unlike most plant proteins, it contains all the essential amino acids 30. The quality of soy protein has been assessed through several metabolic studies of nitrogen balance 31, 32, 33, which have demonstrated that soy protein supports nitrogen balance on par with beef and milk proteins. One recent study reported that amino acids from soy protein appear in the serum sooner, but that this may lead to a more rapid breakdown of the amino acids in the liver 34. Americans as a whole still consume very little soy protein. Based on 2003 data from the UN Food and Agriculture Organization, per-capita soy protein consumption is less than 1 gram (g) per day in most European and North American countries, although certain subpopulations such as vegetarians, Asian immigrants, and infants fed soy-based formula consume more. The Japanese, on the other hand, consume an average 8.7 g of soy protein per day; Koreans, 6.2–9.6 g; Indonesians, 7.4 g; and the Chinese, 3.4 g 30.

Traditional soy foods include tofu, which is produced by puréeing cooked soybeans and precipitating the solids, and miso and tempeh, which are made by fermenting soybeans with grains. “Second generation” soy products involve chemical extractions and other processing, and include soy protein isolate and soy flour. These products become primary ingredients in items such as meatless burgers, dietary protein supplements, and infant formula, and are also used as nonnutritive additives to improve the characteristics of processed foods 30.

Soy Protein Types

The soybean can be separated into three distinct categories; flour, concentrates, and isolates. Soy flour can be further divided into natural or full-fat (contains natural oils), defatted (oils removed), and lecithinated (lecithin added) forms. Of the three different categories of soy protein products, soy flour is the least refined form. It is commonly found in baked goods. Another product of soy flour is called textured soy flour. This is primarily used for processing as a meat extender. See Table 1 for protein composition of soy flour, concentrates, and isolates.

Soy concentrate was developed in the late 1960s and early 1970s and is made from defatted soybeans. While retaining most of the bean’s protein content, concentrates do not contain as much soluble carbohydrates as flour, making it more palatable. Soy concentrate has a high digestibility and is found in nutrition bars, cereals, and yogurts.

Isolates are the most refined soy protein product containing the greatest concentration of protein, but unlike flour and concentrates, contain no dietary fiber. Isolates originated around the 1950s in The United States. They are very digestible and easily introduced into foods such as sports drinks and health beverages as well as infant formulas.

Table 1: Protein composition of soy protein forms

| Soy Protein Form | Protein Composition |

|---|---|

| Soy Flour | 50% |

| Soy Concentrate | 70% |

| Soy Isolate | 90% |

What we know about Soy

- Consuming soy protein in place of other proteins may lower levels of LDL (“bad”) cholesterol to a small extent 35, 36.

- Soy isoflavone supplements may help to reduce the frequency and severity of menopausal hot flashes, but the effect may be small 37, 38.

- It’s uncertain whether soy supplements can relieve cognitive problems associated with menopause 39.

- Current evidence suggests that soy isoflavone mixtures do not slow bone loss in Western women during or after menopause 40.

- Diets containing soy protein may slightly reduce blood pressure 41.

- There’s not enough scientific evidence to determine whether soy supplements are effective for any other health uses.

- Current National Center for Complementary and Integrative Health-funded studies on soy and its components are investigating a variety of topics, including stroke outcomes, anti-inflammatory effects, and effects on diabetes.

- For recipes you may want to visit The Vegetarian Society Recipes 27

2. Lentils: Lentils are a protein favorite of many, especially those on vegetarian and vegan diets looking to pump up the protein fast. Lentils add 9 grams of protein to your meal per half cup, along with nearly 15 grams of fiber.

3. Tofu: This protein source’s main attractive nature is that it can be flavored however you want and adds a rich, creamy texture or chewy texture to your food depending on if you buy firm or soft tofu.

4. Black Beans: Black beans are one of the richest sources of antioxidants and one of the healthiest beans of all beans and legumes. Their dark color indicates their strong antioxidant content and they also have less starch than some other beans.

5. Quinoa: With 8 grams per cup, this gluten-free seed-like grain is a fantastic source of protein, magnesium, antioxidants, and fiber. You can cook it, bake it, and even stir into stir-fry dishes and more.

6. Amaranth: Amaranth is similar to quinoa and teff (an African cereal which is cultivated almost exclusively in Ethiopia, used mainly to make flour) in its nutritional content, though much tinier in size. This ancient pseudo-grain (also a seed) adds 7 grams of protein to your meals in just one cup of cooked amaranth. It’s also a fantastic source of iron, B vitamins, and magnesium.

7. Soy Milk: Soy milk, which packs 8 grams of protein in just one cup, offers 4 grams of heart-healthy fats and is rich in phytosterols that assist with good heart health.

8. Green Peas: Packed with protein and fiber, peas contain 8 grams of protein per cup, so add a little of these sweet treats throughout the day. Peas are also rich in leucine, an amino acid crucial to metabolism and weight loss that’s hard to find in most plant-based foods.

9. Artichokes: Containing 4 grams of protein in just 1/2 cup, artichoke hearts are a great way to boost fiber, protein, and they are filling but low in calories.

10. Hemp Seeds: Hemp seeds are a complete protein packing 13 grams in just 3 tablespoons, these tiny seeds are easy to add anywhere.

11. Oatmeal: Oatmeal has three times the protein of brown rice with less starch and more fiber. It’s also a great source of magnesium, calcium and B vitamins.

12. Pumpkin Seeds: Pumpkin seeds are one of the most overlooked sources of iron and protein out there, containing 8 gram of protein per 1/4 cup. They’re also an excellent source of magnesium as well.

13. Chia Seeds: Chia has 5 grams of protein per 2 tablespoons and is also a complete protein source.

14. Tempeh: Tempeh is a fermented form of soy that’s high in protein, easy to digest, and rich in probiotics.

15. Hemp Milk: Hemp milk is becoming more and more popular just like other plant-based milks. Hemp milk packs 5 grams in one cup. You can make your own by blending 1/4 cup hemp seeds with 2 cups of water, straining, and using like you would almond milk. You don’t have to soak hemp seeds like you do almonds, and can adjust the ratio of seeds to water depending on how rich and creamy you’d like your milk.

16. Edamame: Filled with antioxidants and fiber, not to mention protein, edamame is the young green soybean and so delicious! It’s filled with a nutty sweetness and packs in 8.5 grams of protein in just 1/2 cup. You can even snack on it raw and roast it like chickpeas for a crunchy snack.

17. Spinach: Filled with 5 grams of protein per cup, spinach is a great leafy green to enjoy as much as you can.

18. Black Eyed Peas: Black eyed peas might seem boring, but they pack 8 grams of protein in just 1/2 cup. Like most other beans, they’re also a great source of iron, magnesium, potassium, and B vitamins.

19. Broccoli: This lovely veggie contains 4 grams of protein in just 1 cup, which isn’t too bad considering that same cup also contains 30 percent of your daily calcium needs, along with vitamin C, fiber, and B vitamins.

20. Asparagus: Filled with 4 grams per cup (about 4-6 stalks, chopped), asparagus is also a great source of B vitamins and folate.

21. Green Beans: Green beans pack 4 grams of protein in just 1/2 cup, along with vitamin B6, and they’re low in carbs but high in fiber.

22. Almonds: Almonds have 7 grams per cup of fresh nuts or in 2 tablespoons of almond butter.

23. Spirulina: This blue green algae is so easy to use, especially if you add it to a smoothie with other ingredients like berries, cacao or some banana. Spirulina adds 80 percent of your daily iron needs and 4 grams of protein in one tablespoon; it’s also a complete amino acid source.

24. Tahini: This yummy spread that can be used anywhere nut butters can is just filled with filling protein. Containing 8 grams in two tablespoons, tahini is also a fantastic source of iron and B vitamins, along with magnesium and potassium.

25. Nutritional Yeast: This cheesy ingredient was packed with so much nutrition. Nutritional yeast contains 8 grams of protein in just 2 tablespoons.

26. Chickpeas: Not just for hummus, a 1/2 cup of chickpeas will also give you a nice dose of protein (6-8 grams depending on the brand). You can also use hummus, though note that it’s not as high in servings as chickpeas since it contains other ingredients.

27. Peanut Butter: Just 2 tablespoons also gives you 8 grams of pure, delicious protein.

28. Teff: Teff is the tiniest grain-like seed to exist and is one of the most fast-growing grains. One pound of teff grain can quickly turn into one ton just within 12 weeks of its growing cycle. That’s twice as fast as wheat, which is the main reason it’s known as the Ethiopians’ choice food. Teff has been used for years to protect Ethiopians from famine and hunger, along with provide their bodies with nutrients to sustain them for long periods of time. Teff also contains more protein than quinoa, with 7 grams in just 1/4 of a cup. In that same serving you’ll also get 4 grams of fiber, which makes this grain a fantastic choice for your digestion. Just one serving of teff provides 123 milligrams of calcium, which is more than any other grain and about as much as a cup of spinach. Teff also contains 20 percent of your daily iron needs and 25 percent of your daily magnesium requirements, which can help regulate your metabolism, enhance energy, maintain regularity, and help you relax and rest.

Finding balance, choosing the right kind and amount of protein.

- When choosing protein, opt for low-fat options, such as lean meats, skim milk or other foods with high levels of protein. Legumes, for example, can pack about 16 grams of protein per cup and are a low-fat and inexpensive alternative to meat.

Choose main dishes that combine meat and vegetables together, such as low-fat soups, or a stir-fry that emphasizes veggies.

- Some high-protein foods are healthier than others because of what comes along with the protein: healthy fats or harmful ones, beneficial fiber or hidden salt. It’s this protein package that’s likely to make a difference for health. For example, a 6-ounce broiled porterhouse steak is a great source of protein—about 40 grams worth. But it also delivers about 12 grams of saturated fat 42. For someone who eats a 2,000 calorie per day diet, that’s more than 60 percent of the recommended daily intake for saturated fat.

- Watch portion size. Aim for 2- to 3-ounce servings.

- If you’re having an appetizer, try a plate of raw veggies instead of a cheese plate. Cheese adds protein, but also fat.

- A 6-ounce ham steak has only about 2.5 grams of saturated fat, but it’s loaded with sodium—2,000 milligrams worth, or about 500 milligrams more than the daily sodium max.

6-ounces of wild salmon has about 34 grams of protein and is naturally low in sodium, and contains only 1.7 grams of saturated fat 42. Salmon and other fatty fish are also excellent sources of omega-3 fats, a type of fat that’s especially good for the heart. Alternatively, a cup of cooked lentils provides about 18 grams of protein and 15 grams of fiber, and it has virtually no saturated fat or sodium 42.

The Vegetarian Society’s Vegetarian sources of protein 43 include:

- Nuts, beans and pulses, such as quinoa – these have very high levels of protein

- Cheese

- Eggs – have the perfect balance of amino acids

- Soya is very versatile and found in soya milk, tofu, miso and ready made products such as burgers and sausages

- Quorn is a form of myco-protein and sold in a range of forms

- Rice, grains, pasta, bread and potatoes, although not generally known for their protein, play an important part in your protein intake

Vegetarian food of animal origin such as cheese, milk and eggs have a good balance of essential amino acids. However, food groups such as cereals, rice and legumes (peas, lentils and beans) have an imbalance of 2 of the essential amino acids. To provide a ‘complete’ protein, containing a balance of all 8 essential amino acids, it is recommended to consume a combination of cereals and legumes in your diet e.g. beans on toast.

Protein and Chronic Diseases

Proteins in food and the environment are responsible for food allergies, which are overreactions of the immune system. Beyond that, relatively little evidence has been gathered regarding the effect of the amount of dietary protein on the development of chronic diseases in healthy people.

However, there’s growing evidence that high-protein food choices do play a role in health—and that eating healthy protein sources like fish, chicken, beans, or nuts in place of red meat (including processed red meat) can lower the risk of several diseases and premature death 4, 44, 45, 46, 47, 48, 49.

Cardiovascular disease

Research conducted at Harvard School of Public Health has found that eating even small amounts of red meat, especially processed red meat, on a regular basis is linked to an increased risk of heart disease and stroke, and the risk of dying from cardiovascular disease or any other cause 44, 46, 50. Conversely, replacing red and processed red meat with healthy protein sources such as poultry, fish, or beans seems to reduce these risks.

One investigation followed 120,000 men and women in the Nurses’ Health Study and Health Professionals Follow-Up Study for more than two decades 46. For every additional 3-ounce serving of unprocessed red meat the study participants consumed each day, their risk of dying from cardiovascular disease increased by 13 percent.

Processed red meat was even more strongly linked to dying from cardiovascular disease—and in smaller amounts: Every additional 1.5 ounce serving of processed red meat consumed each day—equivalent to one hot dog or two strips of bacon—was linked to a 20 percent increase in the risk of cardiovascular disease death.

Cutting back on red meat could save lives: the researchers estimated that if all the men and women in the study had reduced their total red and processed red meat intake to less than half a serving a day, one in ten cardiovascular disease deaths would have been prevented.

In terms of the amount of protein consumed, there’s evidence that eating a high-protein diet may be beneficial for the heart, as long as the protein comes from a healthy source.

A 20-year prospective study of over 80,000 women found that those who ate low-carbohydrate diets that were high in vegetable sources of fat and protein had a 30 percent lower risk of heart disease compared with women who ate high-carbohydrate, low-fat diets. Diets were given low-carbohydrate scores based on their intake of fat, protein, and carbohydrates 51. However, eating a low-carbohydrate diet high in animal fat or protein did not offer such protection.

Further evidence of the heart benefits of eating healthy protein in place of carbohydrate comes from a randomized trial known as the Optimal Macronutrient Intake Trial for Heart Health (OmniHeart). A healthy diet that replaced some carbohydrate with healthy protein (or healthy fat) did a better job of lowering blood pressure and harmful low-density lipoprotein (LDL) cholesterol than a similarly healthy, higher carbohydrate diet 52.

Similarly, the “EcoAtkins” weight loss trial compared a low-fat, high -carbohydrate, vegetarian diet to a low-carbohydrate vegan diet that was high in vegetable protein and fat. Though weight loss was similar on the two diets, study participants on the high protein diet saw improvements in blood lipids and blood pressure 53.

A more recent study generated headlines because it had the opposite result. In that study, Swedish women who ate low-carbohydrate, high-protein diets had higher rates of cardiovascular disease and death than those who ate lower-protein, higher-carbohydrate diets 54. But the study, which assessed the women’s diets only once and then followed them for 15 years, did not look at what types of carbohydrates or what sources of protein these women ate. That was important because most of the women’s protein came from animal sources.

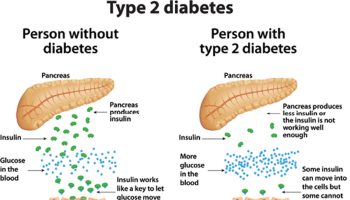

Diabetes

Again, protein quality matters more than protein quantity when it comes to diabetes risk 55.

A recent study found that people who ate diets high in red meat, especially processed red meat, had a higher risk of type 2 diabetes than those who rarely ate red or processed meat 47. For each additional serving a day of red meat or processed red meat that study participants ate, their risk of diabetes rose 12 and 32 percent, respectively.

Substituting one serving of nuts, low-fat dairy products, or whole grains for a serving of red meat each day lowered the risk of developing type 2 diabetes by an estimated 16 to 35 percent.

Another study also shows that red meat consumption may increase risk of type 2 diabetes. Researchers found that people who started eating more red meat than usual were found to have a 50% increased risk of developing type 2 diabetes during the next four years, and researchers also found that those who reduced red meat consumption lowered their type 2 diabetes risk by 14% over a 10-year follow-up period.

More evidence that protein quality matters comes from a 20-year study that looked at the relationship between low-carbohydrate diets and type 2 diabetes in women. Low-carbohydrate diets that were high in vegetable sources of fat and protein modestly reduced the risk of type 2 diabetes 56. But low-carbohydrate diets that were high in animal sources of protein or fat did not show this benefit.

For type 1 diabetes (formerly called juvenile or insulin-dependent diabetes), proteins found in cow’s milk have been implicated in the development of the disease in babies with a predisposition to the disease, but research remains inconclusive 57, 58.

Cancer

When it comes to cancer, protein quality again seems to matter more than quantity. Research on the association between protein and cancer is ongoing, but some data shows that eating a lot of red meat and processed meat is linked to an increased risk of colon cancer 4.

In the Nurse’s Health Study and the Health Professionals Follow-Up Study, every additional serving per day of red meat or processed red meat was associated with a 10 and 16 percent higher risk of cancer death, respectively 46.

A 2014 study showed that higher consumption of red meat during adolescence was associated with premenopausal breast cancer, suggesting that choosing other protein sources in adolescence may decrease premenopausal breast cancer risk 59.

People should aim to reduce overall consumption of red meat and processed meat, but when you do opt to have it, go easy on the grill. High-temperature grilling creates potentially cancer-causing compounds in meat, including polycyclic aromatic hydrocarbons and heterocyclic amines. You don’t have to stop grilling, but try these tips for healthy grilling from the American Institute of Cancer Research: Marinate meat before grilling it, partially pre-cook meat in the oven or microwave to reduce time on the grill, and grill over a low flame.

In October 2015, the World Health Organization (WHO)’s International Agency for Research on Cancer announced that consumption of processed meat is “carcinogenic to humans,” and that consumption of red meat is “probably carcinogenic to humans.” 60

The IARC Working Group, comprised of 22 scientists from ten countries, evaluated over 800 studies. Conclusions were primarily based on the evidence for colorectal cancer. Data also showed positive associations between processed meat consumption and stomach cancer, and between red meat consumption and pancreatic and prostate cancer 60.

Osteoporosis

Digesting protein releases acids into the bloodstream, which the body usually neutralizes with calcium and other buffering agents. Eating lots of protein, then, requires a lot of calcium – and some of this may be pulled from bone.

Following a high-protein diet for a long period of time could weaken bone. In the Nurses’ Health Study, for example, women who ate more than 95 grams of protein a day were 20 percent more likely to have broken a wrist over a 12-year period when compared with those who ate an average amount of protein (less than 68 grams a day) 61. This area of research is still controversial, however, and the findings have not been consistent. Some studies suggest that increasing protein increases risk of fractures; others have linked high-protein diets with increased bone-mineral density, and thus stronger bones 62, 63, 64.

Protein and Weight Control

The same high-protein foods that are good choices for disease prevention may also help with weight control. Researchers at Harvard School of Public Health followed the diet and lifestyle habits of 120,000 men and women for up to 20 years, looking at how small changes contributed to weight gain over time 65.

Those who ate more red and processed meat over the course of the study gained more weight, about one extra pound every four years, while those who ate more nuts over the course of the study gained less weight, about a half pound less every four years.

One study showed that eating approximately one daily serving of beans, chickpeas, lentils or peas can increase fullness, which may lead to better weight management and weight loss 66.

There’s no need to go overboard on protein. Though some studies show benefits of high-protein, low-carbohydrate diets in the short term, avoiding fruits and whole grains means missing out on healthful fiber, vitamins, minerals, and other phytonutrients.

Summary

Diets high in plant-based proteins and fats can provide health benefits, so try mixing some vegetarian proteins into your meals. Going meatless can be good for your wallet as well as your health, since beans, nuts and seeds, and other minimally-processed vegetarian protein sources are often less expensive than meat. Eating plant protein in place of meat is also good for the planet. It takes a lot of energy to raise and process animals for meat, so going meatless could help reduce pollution and has the potential to lessen climate change. With a proper combination of sources, vegetable proteins may provide similar benefits as protein from animal sources. Maintenance of lean body mass though may become a concern. However, interesting data does exist concerning health benefits associated with soy protein consumption. Tofu and other soy foods are an excellent red meat alternative. In some cultures, tofu and soy foods are a protein staple, and we don’t suggest any change. But if you haven’t grown up eating lots of soy, there’s no reason to begin eating it in large quantities. And stay away from supplements that contain concentrated soy protein or extracts, such as isoflavones, as we just don’t know their long-term effects.

Cutting back on highly processed carbohydrates and increasing protein improves levels of triglycerides and protective high-density lipoprotein (HDL) in the bloodstream, and so may reduce your chances of having a heart attack, stroke, or other type of cardiovascular disease. This shift may also make you feel full longer, and stave off hunger pangs 67.

NOTE: When your body uses protein, it produces waste. This waste is removed by the kidneys. Too much protein can make the kidneys work harder, so people with chronic kidney disease may need to eat less protein.

References- The National Kidney Disease Education Program. Protein – tips for people with chronic kidney disease. https://www.niddk.nih.gov/health-information/health-communication-programs/nkdep/a-z/nutrition-protein/Documents/nutrition-protein-508.pdf

- Harvard University, Harvard School of Public Health. Protein. https://www.hsph.harvard.edu/nutritionsource/what-should-you-eat/protein/

- Institute of Medicine, Dietary Reference Intakes for Energy, Carbohydrate, Fiber, Fat, Fatty Acids, Cholesterol, Protein, and Amino Acids (Macronutrients). 2005, National Academies Press: Washington, DC. http://www.nationalacademies.org/hmd/

- Food, Nutrition, Physical Activity, and the Prevention of Cancer: a Global Perspective. 2007, World Cancer Research Fund, American Institute for Cancer Research.: Washington, DC. http://www.aicr.org/assets/docs/pdf/reports/Second_Expert_Report.pdf

- National Institute of General Medical Sciences. Chapter 1: Proteins are the Body’s Worker Molecules. https://publications.nigms.nih.gov/structlife/chapter1.html

- U.S. National Library of Medicine. Medline Plus. Amino acids. https://medlineplus.gov/ency/article/002222.htm

- Brosnan J (2003). “Interorgan amino acid transport and its regulation”. J Nutr 133 (6 Suppl 1): 2068S-2072S.

- Young V, Ajami A (2001). “Glutamine: the emperor or his clothes?”. J Nutr 131 (9 Suppl): 2449S-59S; discussion 2486S-7S.

- Wikipedia. Ketogenic amino acid. https://en.wikipedia.org/wiki/Ketogenic_amino_acid

- Dietary Reference Intakes for Energy, Carbohydrate, Fiber, Fat, Fatty Acids, Cholesterol, Protein, and Amino Acids (Macronutrients) ( 2005 ) /10 Protein and Amino Acids. https://www.nap.edu/read/10490/chapter/12#593

- J Sports Sci Med. 2004 Sep; 3(3): 118–130. International Society of Sports Nutrition Symposium, June 18-19, 2005, Las Vegas NV, USA – Symposium – Macronutrient Utilization During Exercise: Implications For Performance And Supplementation. Protein – Which is Best ? https://www.ncbi.nlm.nih.gov/pmc/articles/PMC3905294/

- Effects of an omnivorous diet compared with a lactoovovegetarian diet on resistance-training-induced changes in body composition and skeletal muscle in older men. Campbell WW, Barton ML Jr, Cyr-Campbell D, Davey SL, Beard JL, Parise G, Evans WJ. Am J Clin Nutr. 1999 Dec; 70(6):1032-9. https://www.ncbi.nlm.nih.gov/pubmed/10584048/

- Effect of protein source and quantity on protein metabolism in elderly women. Pannemans DL, Wagenmakers AJ, Westerterp KR, Schaafsma G, Halliday D. Am J Clin Nutr. 1998 Dec; 68(6):1228-35. https://www.ncbi.nlm.nih.gov/pubmed/9846851/

- Whey protein concentrate (WPC) and glutathione modulation in cancer treatment. Bounous G. Anticancer Res. 2000 Nov-Dec; 20(6C):4785-92. https://www.ncbi.nlm.nih.gov/pubmed/11205219/

- Functional properties of whey, whey components, and essential amino acids: mechanisms underlying health benefits for active people (review). Ha E, Zemel MB. J Nutr Biochem. 2003 May; 14(5):251-8. https://www.ncbi.nlm.nih.gov/pubmed/12832028/

- Branched-chain amino acids augment ammonia metabolism while attenuating protein breakdown during exercise. MacLean DA, Graham TE, Saltin B. Am J Physiol. 1994 Dec; 267(6 Pt 1):E1010-22. https://www.ncbi.nlm.nih.gov/pubmed/7810616/

- Geiser M. (2003) The wonders of whey protein. NSCA’s Performance Training Journal 2, 13-15

- Infusion of soy and casein protein meals affects interorgan amino acid metabolism and urea kinetics differently in pigs. Deutz NE, Bruins MJ, Soeters PB. J Nutr. 1998 Dec; 128(12):2435-45. https://www.ncbi.nlm.nih.gov/pubmed/9868192/

- Slow and fast dietary proteins differently modulate postprandial protein accretion. Boirie Y, Dangin M, Gachon P, Vasson MP, Maubois JL, Beaufrère B. Proc Natl Acad Sci U S A. 1997 Dec 23; 94(26):14930-5. https://www.ncbi.nlm.nih.gov/pubmed/9405716/

- Purification and characterization of cell growth factor in bovine colostrum. Kishikawa Y, Watanabe T, Watanabe T, Kubo S. J Vet Med Sci. 1996 Jan; 58(1):47-53. https://www.ncbi.nlm.nih.gov/pubmed/8645756/

- Effects of bovine colostrum supplementation on serum IGF-I, IgG, hormone, and saliva IgA during training. Mero A, Miikkulainen H, Riski J, Pakkanen R, Aalto J, Takala T. J Appl Physiol (1985). 1997 Oct; 83(4):1144-51. https://www.ncbi.nlm.nih.gov/pubmed/9338422/

- The effects of bovine colostrum supplementation on body composition and exercise performance in active men and women. Antonio J, Sanders MS, Van Gammeren D. Nutrition. 2001 Mar; 17(3):243-7. https://www.ncbi.nlm.nih.gov/pubmed/11312068/

- Bovine colostrum supplementation does not affect plasma buffer capacity or haemoglobin content in elite female rowers. Brinkworth GD, Buckley JD. Eur J Appl Physiol. 2004 Mar; 91(2-3):353-6. https://www.ncbi.nlm.nih.gov/pubmed/14685867/

- The effect of bovine colostrum supplementation on exercise performance in elite field hockey players. Hofman Z, Smeets R, Verlaan G, Lugt Rv, Verstappen PA. Int J Sport Nutr Exerc Metab. 2002 Dec; 12(4):461-9. https://www.ncbi.nlm.nih.gov/pubmed/12500989/

- Rockström J, Willett W, Stordalen GA. An American Plate That Is Palatable for Human and Planetary Health. Huffington Post. March 26, 2015. http://www.huffingtonpost.com/johan-rockstrom/post_9225_b_6949716.html

- Barclay E. A Nation of Meat Eaters: See How It All Adds Up. NPR. June 27, 2012. http://www.npr.org/sections/thesalt/2012/06/27/155527365/visualizing-a-nation-of-meat-eaters

- The Vegetarian Society Recipes. Vegetarian Society Recipes. http://www.recipes.vegsoc.org/

- National Center for Complementary and Integrative Health. Soy. https://nccih.nih.gov/health/soy/ataglance.htm

- Enderlin CA, Coleman EA, Stewart CB, et al.: Dietary soy intake and breast cancer risk. Oncol Nurs Forum 36 (5): 531-9, 2009. https://www.ncbi.nlm.nih.gov/pubmed/19726393?dopt=Abstract

- Environ Health Perspect. 2006 Jun; 114(6): A352–A358. The Science of Soy: What Do We Really Know ? https://www.ncbi.nlm.nih.gov/pmc/articles/PMC1480510/

- Young VR, Puig M, Queiroz E, Scrimshaw NS, Rand WM. Evaluation of the protein quality of an isolated soy protein in young men: relative nitrogen requirements and effects of methionine supplementation. Am J Clin Nutr. 1984;39:16–24. https://www.ncbi.nlm.nih.gov/pubmed/6537870/

- Baglieri A, Mahe S, Zidi S, Huneau JF, Thuillier F, Marteau P, Tome D. Gastro-jejunal digestion of soya-bean-milk protein in humans. Br J Nutr. 1994;72:519–532. doi: 10.1079/BJN19940056. https://www.ncbi.nlm.nih.gov/pubmed/7986784

- Mariotti F, Mahe S, Benamouzig R, Luengo C, Dare S, Gaudichon C, Tome D. Nutritional value of [15N]-soy protein isolate assessed from ileal digestibility and postprandial protein utilization in humans. J Nutr. 1999;129:1992–1997. https://www.ncbi.nlm.nih.gov/pubmed/10539774/

- Bos C, Metges CC, Gaudichon C, Petzke KJ, Pueyo ME, Morens C, Everwand J, Benamouzig R, Tome D. Postprandial kinetics of dietary amino acids are the main determinant of their metabolism after soy or milk protein ingestions in humans. J Nutr. 2003;133:1308–1315. https://www.ncbi.nlm.nih.gov/pubmed/12730415

- Anderson JW, Bush HM. Soy protein effects on serum lipoproteins: a quality assessment and meta-analysis of randomized, controlled studies. Journal of the American College of Nutrition. 2011;30(2):79-91. https://www.ncbi.nlm.nih.gov/pubmed/21730216

- Fed Regist. 1999 Oct 26;64(206):57700-33. Food labeling: health claims; soy protein and coronary heart disease. Food and Drug Administration, HHS. Final rule. https://www.ncbi.nlm.nih.gov/pubmed/11010706?dopt=Abstract

- Lethaby A, Marjoribanks J, Kronenberg F, et al. Phytoestrogens for menopausal vasomotor symptoms. Cochrane Database of Systematic Reviews. 2013;(12):CD001395. http://onlinelibrary.wiley.com/doi/10.1002/14651858.CD001395.pub4/full

- Taku K, Melby MK, Kronenberg F, et al. Extracted or synthesized soybean isoflavones reduce menopausal hot flash frequency and severity: systematic review and meta-analysis of randomized controlled trials. Menopause. 2012;19(7):776-790. https://www.ncbi.nlm.nih.gov/pubmed/22433977

- Clement YN, Onakpoya I, Hung SK, et al. Effects of herbal and dietary supplements on cognition in menopause: a systematic review. Maturitas. 2011;68(3):256-263. https://www.ncbi.nlm.nih.gov/pubmed/21237589

- Ricci E, Cipriani S, Chiaffarino F, et al. Soy isoflavones and bone mineral density in perimenopausal and postmenopausal Western women: a systematic review and meta-analysis of randomized controlled trials. Journal of Women’s Health. 2010;19(9):1609-1617. https://www.ncbi.nlm.nih.gov/pubmed/20673147

- Dong J-Y, Tong X, Wu Z-W, et al. Effect of soya protein on blood pressure: a meta-analysis of randomised controlled trials. British Journal of Nutrition. 2011;106(3):317-326. https://www.ncbi.nlm.nih.gov/pubmed/21342608

- Agriculture, U.D.o., USDA Nutrient Database for Standard Reference, Release 14. 2005.

- The Vegetarian Society. Protein. https://www.vegsoc.org/facts/protein

- Bernstein, A.M., et al., Major dietary protein sources and risk of coronary heart disease in women. Circulation, 2010. 122(9): p. 876-83. https://www.ncbi.nlm.nih.gov/pubmed/20713902

- Aune, D., G. Ursin, and M.B. Veierod, Meat consumption and the risk of type 2 diabetes: a systematic review and meta-analysis of cohort studies. Diabetologia, 2009. 52(11): p. 2277-87. https://www.ncbi.nlm.nih.gov/pubmed/19662376

- Pan, A., et al., Red meat consumption and mortality: results from 2 prospective cohort studies. Arch Intern Med, 2012. 172(7): p. 555-63. https://www.ncbi.nlm.nih.gov/pubmed/22412075

- Pan, A., et al., Red meat consumption and risk of type 2 diabetes: 3 cohorts of US adults and an updated meta-analysis. Am J Clin Nutr, 2011. 94(4): p. 1088-96. https://www.ncbi.nlm.nih.gov/pubmed/21831992

- Bernstein, A.M., et al., Dietary protein sources and the risk of stroke in men and women. Stroke, 2012. 43(3): p. 637-44. www.ncbi.nlm.nih.gov/pubmed/22207512

- Song, M., Fung, T.T., Hu, F.B., et al. Association of Animal and Plant Protein Intake With All-Cause and Cause-Specific Mortality. JAMA Intern Med. Published online August 01, 2016. https://www.hsph.harvard.edu/news/hsph-in-the-news/healthy-eating-red-meat-stroke-hu/

- Bernstein, A.M., et al., Dietary protein sources and the risk of stroke in men and women. Stroke, 2012. 43(3): p. 637-44. https://www.ncbi.nlm.nih.gov/pubmed/22207512

- Halton, T.L., et al., Low-carbohydrate-diet score and the risk of coronary heart disease in women. N Engl J Med, 2006. 355(19): p. 1991-2002. https://www.ncbi.nlm.nih.gov/pubmed/17093250

- Appel, L.J., et al., Effects of protein, monounsaturated fat, and carbohydrate intake on blood pressure and serum lipids: results of the OmniHeart randomized trial. JAMA, 2005. 294(19): p. 2455-64. https://www.ncbi.nlm.nih.gov/pubmed/16287956

- Jenkins, D.J., et al., The effect of a plant-based low-carbohydrate (“Eco-Atkins”) diet on body weight and blood lipid concentrations in hyperlipidemic subjects. Arch Intern Med, 2009. 169(11): p. 1046-54. https://www.ncbi.nlm.nih.gov/pubmed/19506174

- Lagiou, P., et al., Low carbohydrate-high protein diet and incidence of cardiovascular diseases in Swedish women: prospective cohort study. BMJ, 2012. 344: p. e4026. https://www.ncbi.nlm.nih.gov/pubmed/22735105

- Ley, S. H., Sun, Q., Willett, W. C., Eliassen, A. H., Wu, K., Pan, A., … & Hu, F. B. (2014). Associations between red meat intake and biomarkers of inflammation and glucose metabolism in women. Am J Clin Nutr, February 2014. http://ajcn.nutrition.org/content/early/2013/11/27/ajcn.113.075663.short

- Halton, T.L., et al., Low-carbohydrate-diet score and risk of type 2 diabetes in women. Am J Clin Nutr, 2008. 87(2): p. 339-46. www.ncbi.nlm.nih.gov/pubmed/18258623

- Akerblom, H.K., et al., Environmental factors in the etiology of type 1 diabetes. Am J Med Genet, 2002. 115(1): p. 18-29. https://www.ncbi.nlm.nih.gov/pubmed/12116173

- Vaarala, O., et al., Removal of Bovine Insulin From Cow’s Milk Formula and Early Initiation of Beta-Cell Autoimmunity in the FINDIA Pilot Study. Arch Pediatr Adolesc Med, 2012. https://www.ncbi.nlm.nih.gov/pubmed/22393174

- Farvid MS, Cho E, Chen WY, Eliassen AH, Willett WC. Adolescent meat intake and breast cancer risk. Int J Cancer, 2014. https://www.ncbi.nlm.nih.gov/pubmed/?term=farvid+cho+adolescent+meat+intake+and+breast+cancer+risk

- Bouvard V, Loomis D, Guyton KZ, Grosse Y, Ghissassi FE, Benbrahim-Tallaa L, Guha N1, Mattock H, Straif K; International Agency for Research on Cancer Monograph Working Group (2015). Carcinogenicity of consumption of red and processed meat. Lancet Oncol doi: 10.1016/S1470-2045(15)00444-1. https://www.ncbi.nlm.nih.gov/pubmed/?term=26514947

- Feskanich, D., et al., Protein consumption and bone fractures in women. Am J Epidemiol, 1996. 143(5): p. 472-9. https://www.ncbi.nlm.nih.gov/pubmed/8610662

- Darling, A.L., et al., Dietary protein and bone health: a systematic review and meta-analysis. Am J Clin Nutr, 2009. 90(6): p. 1674-92. https://www.ncbi.nlm.nih.gov/pubmed/19889822

- Kerstetter, J.E., A.M. Kenny, and K.L. Insogna, Dietary protein and skeletal health: a review of recent human research. Curr Opin Lipidol, 2011. 22(1): p. 16-20. https://www.ncbi.nlm.nih.gov/pubmed/21102327

- Bonjour, J.P., Protein intake and bone health. Int J Vitam Nutr Res, 2011. 81(2-3): p. 134-42. https://www.ncbi.nlm.nih.gov/pubmed/22139564

- Mozaffarian, D., et al., Changes in diet and lifestyle and long-term weight gain in women and men. N Engl J Med, 2011. 364(25): p. 2392-404. http://www.nejm.org/doi/full/10.1056/NEJMoa1014296

- Li SS, Kendall CW, de Souza RJ, Jayalath VH, Cozma AI, Ha V, Mirrahimi A, Chiavaroli L, Augustin LS, Blanco Mejia S, Leiter LA, Beyene J, Jenkins DJ, Sievenpiper JL. Dietary pulses, satiety and food intake: a systematic review and meta-analysis of acute feeding trials. Obesity, 2014. Aug;22(8):1773-80. https://www.ncbi.nlm.nih.gov/pubmed/24820437

- Harvard University, Harvard School of Public Health. 5 Quick tips: Choosing healthy protein foods. https://www.hsph.harvard.edu/nutritionsource/2014/02/12/5-quick-tips-choosing-healthy-protein-foods/