Male or female pattern baldness

Male-pattern baldness also called ‘androgenetic alopecia’ typically appears first at the hairline or top of the head. The typical pattern of male pattern baldness begins at the hairline. The hairline gradually moves backward (recedes) and forms an “M” shape. Eventually the hair becomes finer, shorter, and thinner, and creates a U-shaped (or horseshoe) pattern of hair around the sides of the head. It can progress to partial or complete baldness. Male-pattern baldness is the most common type of hair loss. Male-pattern baldness affects all men to some degree as they get older. For a few men, this process starts as early as the late teens. By the age of 60, most men have some degree of hair loss. Each strand of hair sits in a tiny hole in the skin called a hair follicle. In general, baldness occurs when the hair follicle shrinks over time, resulting in shorter and finer hair. Eventually, the hair follicle does not grow new hair. The hair follicles remain alive, which suggests that it is still possible to grow new hair. Significant balding affects about one in five men (20%) in their 20s, about one in three men (30%) in their 30s and nearly half of men (40%) in their 40s.

Male-pattern baldness is caused when hair follicles are oversensitive to the hormone dihydrotestosterone (DHT), produced by the male hormone, testosterone. Dihydrotestosterone (DHT) causes the follicles to shrink and eventually stop functioning. Both men and women produce this hormone in different amounts.

The involvement of testosterone in balding has led to the myth that going bald is a sign of virility. But men with male-pattern baldness don’t have more male hormones than other men. Their hair follicles are simply more sensitive to the hormones.

Male pattern baldness is usually not a sign of an underlying medical disorder. Hair loss is usually permanent.

While hair loss is a normal part of the ageing process, for some men it can be distressing, particularly if it happens at an early age. Men losing their hair can feel less confident, less attractive and may think it makes them look older; some may feel depressed.

Some men find talking to a counselor helpful if they are feeling worried about their hair loss.

Male-pattern baldness is so called because it tends to follow a set pattern. The first stage is usually a receding hairline, followed by thinning of the hair on the crown and temples. When these two areas meet in the middle, it leaves a horseshoe shape of hair around the back and sides of the head. Eventually, some men go completely bald.

If you have inherited the genes responsible for male-pattern or female-pattern baldness there’s little you can do to prevent it from happening.

Treatments can slow down the process, but there’s no cure. The two most effective treatments for male-pattern baldness are medicines called minoxidil and finasteride. Side-effects are uncommon, but minoxidil can cause skin irritation or a rash in some men.

Current male-pattern baldness treatment options include:

- Hair replacement / transplantation

- Cosmetics

- Micropigmentation (tattoo) to resemble shaven scalp

- Hairpieces

- Minoxidil solution

- Finasteride tablets (type II 5-alpha reductase inhibitor)

- Dutasteride.

There is some evidence that ketoconazole shampoo may also be of benefit, perhaps because it is effective in seborrheic dermatitis and dandruff.

Low level laser therapy is of unproven benefit in pattern balding; one device has been approved by the FDA for marketing. Further studies are required to determine the magnitude of the benefit, if any.

Other treatments for hair loss include wigs, hair transplants and plastic surgery procedures, such as scalp reduction.

As a general rule, it’s easier to maintain existing hair than to regrow it, and once the hair follicle has stopped working it cannot be revived.

Figure 1. Male-pattern baldness

Female-pattern baldness presents as generalized thinning of hair and widening of the scalp parting. The prevalence of female pattern hair loss increases with advancing age, affecting 50% of women during their lifetime 1. Female-pattern baldness typically starts with scalp hairs becoming progressively finer and shorter as you age. Many women first experience hair thinning and hair loss where they part their hair and on the top-central portion of the head. Some affected women also experience thinning at the frontal hairline or temples. There may be an increase in hair shedding. These changes usually lead to a reduction of the hair volume that may be evident by a shrinking hair ponytail. Some women get episodic bursts of accelerated hair shedding for a few months in between longer stable periods of little activity.

In female pattern baldness:

- the hair tends to thin all over the scalp;

- the hair on the top of the head thins and the hair part line (parting) becomes wider; and

- the hairline at the front of the head becomes more sparse.

The reason for female pattern baldness is not well understood, but may be related to:

- Aging

- Changes in the levels of androgens (hormones that can stimulate male features)

- Family history of male or female pattern baldness

Untreated, hair loss in female pattern baldness is permanent. In most cases, hair loss is mild to moderate. You do not need treatment if you are comfortable with your appearance.

Your doctor might prescribe minoxidil, or a cream containing minoxidil. This active ingredient is found in lotions like Hair Revive Extra Strength, Hair Retreva, and Hair A-Gain. It’s important to discuss the potential side effects of these treatments with your doctor. If minoxidil does not work, your doctor may recommend oral tablets such as spironolactone and cyproterone acetate or Androcur®.

Many women find that hair loss can impact on their confidence and self-esteem. Some women may even develop depression. Counseling can help, as can joining a support group where you can share experiences with other people experiencing hair loss. Talk to your doctor if your hair loss is causing you distress.

Figure 2. Female-pattern baldness

Call your doctor if you have hair loss and it continues, especially if you also have itching, skin irritation, or other symptoms. There might be a treatable medical cause for the hair loss.

You should seek medical advice for hair loss if:

- you have recently started a new medicine;

- you are a woman and your hair loss is accompanied by excess growth of facial and body hair or you have acne;

- you have been diagnosed with (or think you may have) an autoimmune disorder such as systemic lupus erythematosis (SLE), nutritional deficiency or thyroid disease;

- you have been recently treated with chemotherapy or have used a hormonal medicine;

- the hair loss occurs in discrete patches;

- the hair loss is associated with scaling or inflammation of the scalp;

- you also have loss of body hair;

- your hair loss is accompanied by changes in the appearance of the underlying skin, which may indicate an infection or skin condition;

- you are aware you have a compulsive hair-pulling habit.

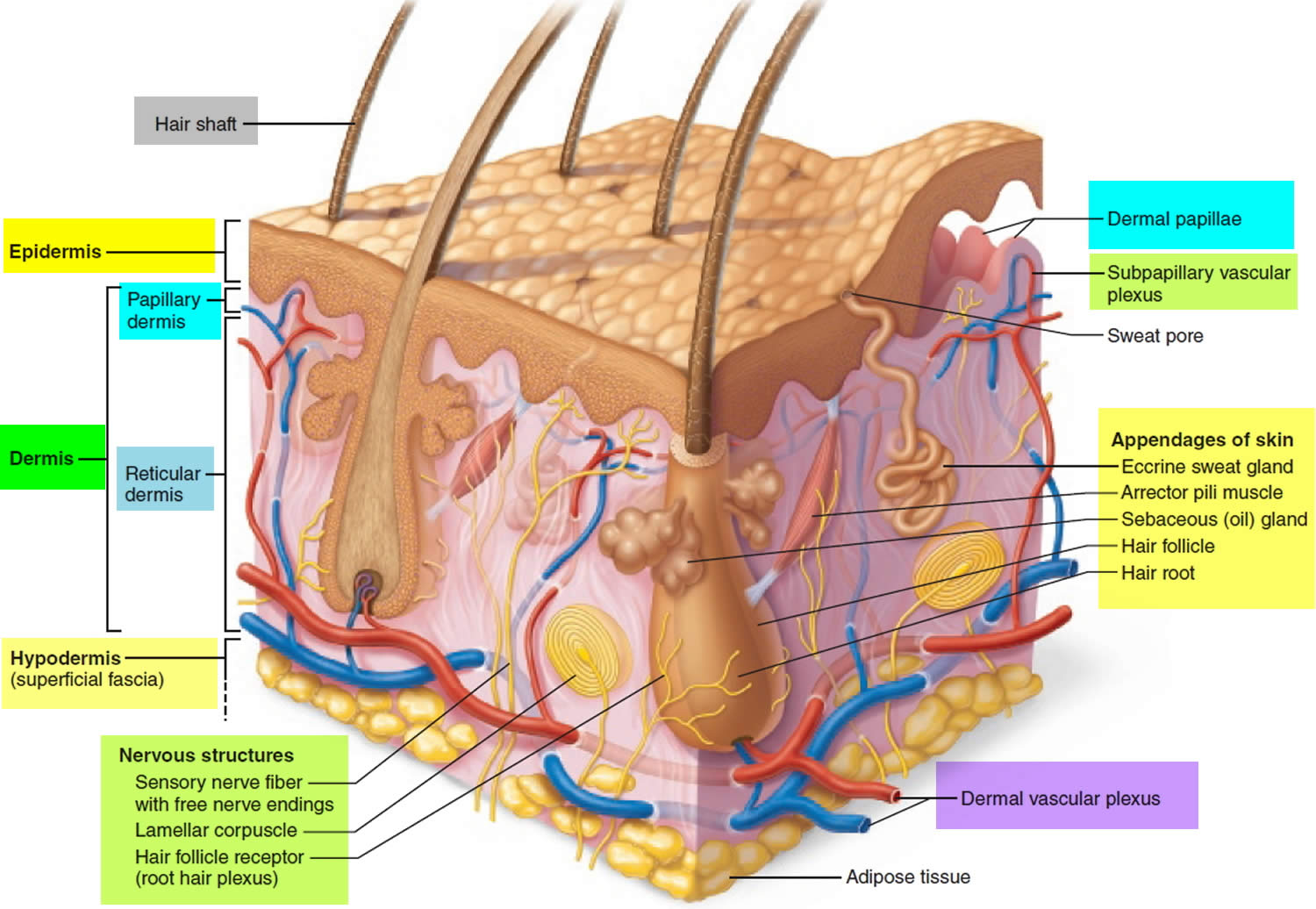

Hair Production

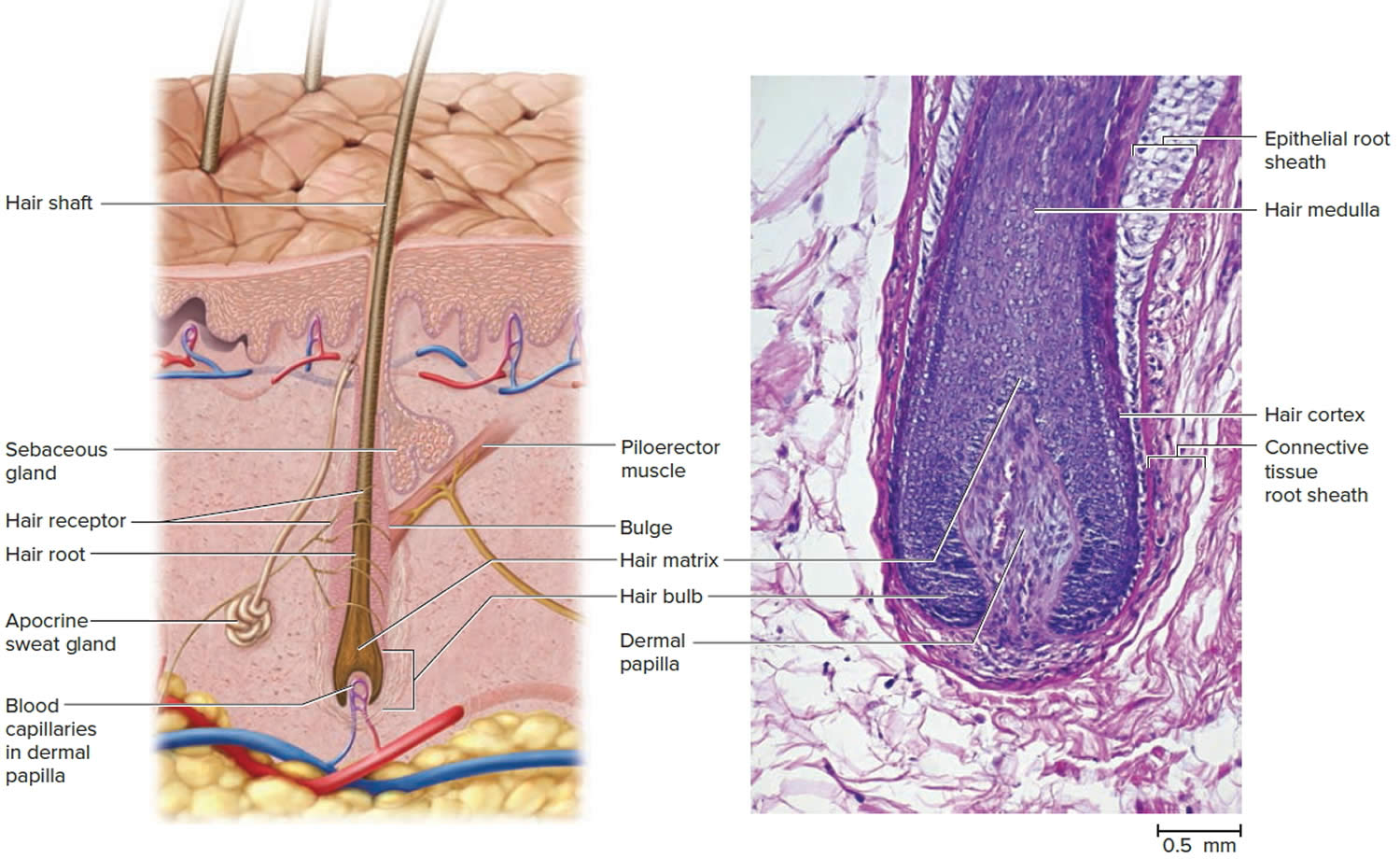

Hair follicles extend deep into the dermis, often projecting into the underlying subcutaneous layer. The epithelium at the follicle base surrounds a small hair papilla, a peg of connective tissue containing capillaries and nerves. The hair bulb consists of epithelial cells that surround the papilla.

Hair production involves a specialized keratinization process. The hair matrix is the epithelial layer involved in hair production. When the superficial basal cells divide, they produce daughter cells that are pushed toward the surface as part of the developing hair. Most hairs have an inner medulla and an outer cortex. The medulla contains relatively soft and flexible soft keratin. Matrix cells closer to the edge of the developing hair form the relatively hard cortex. The cortex contains

hard keratin, which gives hair its stiffness. A single layer of dead, keratinized cells at the outer surface of the hair overlap and form the cuticle that coats the hair.

The hair root anchors the hair into the skin. The root begins at the hair bulb and extends distally to the point where the internal organization of the hair is complete, about halfway to the skin surface. The hair shaft extends from this halfway point to the skin surface, where we see the exposed hair tip.

The size, shape, and color of the hair shaft are highly variable.

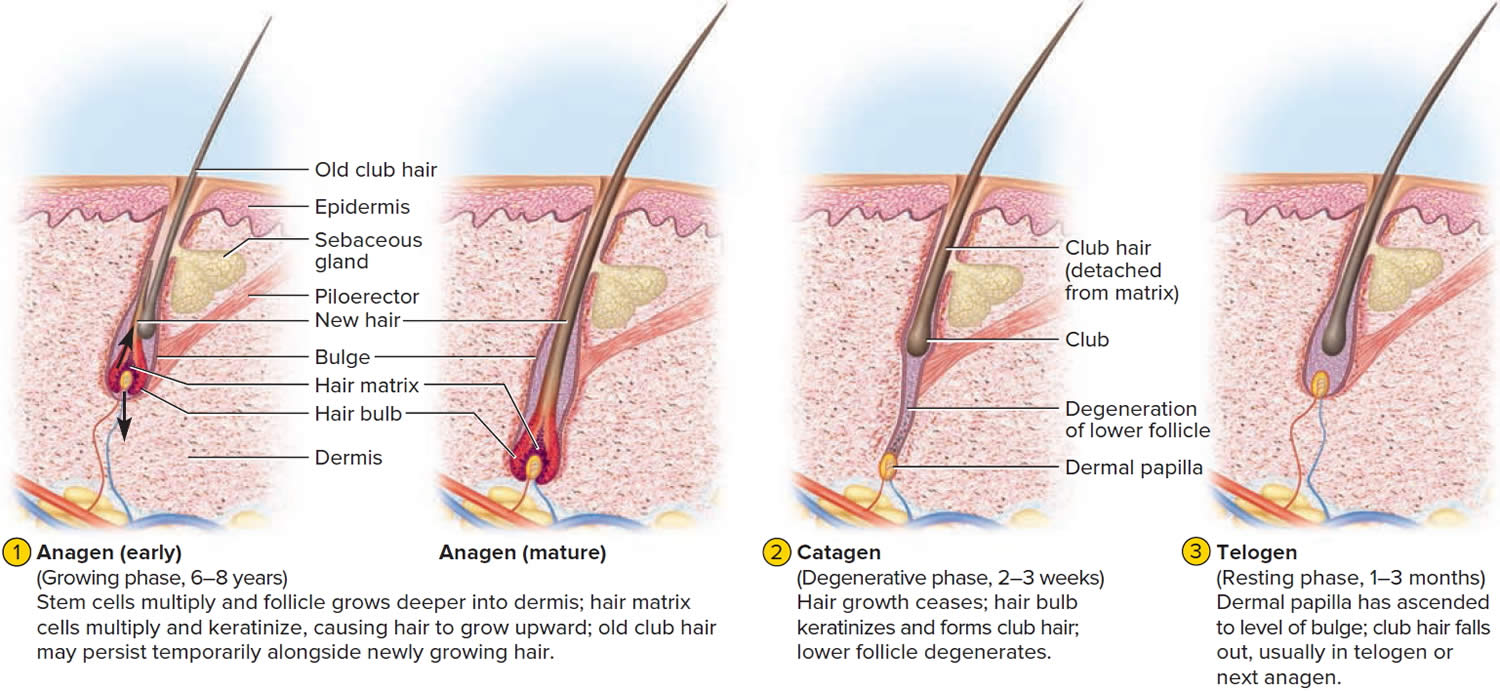

Growth and Replacement of Hair

The human scalp contains about 100,000 hair follicles. These anchor the hair to the skin and contain the cells that produce new hairs. A hair in the scalp grows for two to five years, at a rate of around 0.33 mm/day (about 1/64 inch). Variations in hair growth rate and the duration of the hair growth cycle account for individual differences in uncut hair length. Hair grows in 3 developmental stages:

- Anagen. The anagen phase or actively hair growing phase starts the growing of new hair. The anagen phase is genetically determined and can vary from 2 to 6 years (the average is just under 3 years). Most hair follicles on the scalp are in the anagen phase.

- Catagen. The catagen phase is a transition stage (in-between phase) between the growing and resting phases and lasts 2-3 weeks. The catagen phase is when hair growth stops and the hair follicle shrinks. About 1–3% of hairs are in the catagen phase (in-between phase).

- Telogen. The telogen phase or resting phase is a mature hair with a root, which is held very loosely in the follicle. The telogen phase (resting phase) generally lasts about 4-5 months. Up to 10% of hairs in a normal scalp are in the telogen phase (resting phase). About 100 telogen hairs are lost from the human scalp each day.

At any given time, about 90% of the scalp follicles are in the Anagen stage. In this stage, stem cells from the bulge in the hair follicle multiply and travel downward, pushing the dermal papilla deeper into the skin and forming the epithelial root sheath. Root sheath cells directly above the papilla form the hair matrix. Here, sheath cells transform into hair cells, which synthesize keratin and then die as they are pushed upward away from the papilla. The new hair grows up the follicle, often alongside an old club hair left from the previous cycle.

Hair length depends on the duration of anagen stage. Short hairs (eyelashes, eyebrows, hair on arms and legs) have a short anagen phase of around one month. Anagen lasts up to 6 years or longer in scalp hair.

In the Catagen stage, mitosis in the hair matrix ceases and sheath cells below the bulge die. The follicle shrinks and the dermal papilla draws up toward the bulge. The base of the hair keratinizes into a hard club and the hair, now known as a club hair, loses its anchorage. Club hairs are easily pulled out by brushing the hair, and the hard club can be felt at the hair’s end. When the papilla reaches the bulge, the hair goes into a resting period called the Telogen stage. Eventually, anagen begins anew and the cycle repeats itself. A club hair may fall out during catagen or telogen, or as it is pushed out by the new hair in the next anagen phase.

You lose about 50 to 100 scalp hairs daily. In a young adult, scalp follicles typically spend 6 to 8 years in anagen, 2 to 3 weeks in catagen, and 1 to 3 months in telogen. Scalp hairs grow at a rate of about 1 mm per 3 days (10–18 cm/yr) in the anagen phase.

Hair grows fastest from adolescence until the 40s. After that, an increasing percentage of follicles are in the catagen and telogen phases rather than the growing anagen phase. Hair follicles also shrink and begin producing wispy vellus hairs instead of thicker terminal hairs. Thinning of the hair or baldness, is called alopecia. It occurs to some degree in both sexes and may be worsened by disease, poor nutrition, fever, emotional stress, radiation, or chemotherapy. In the great majority of cases, however, it is simply a matter of aging.

Pattern baldness is the condition in which hair is lost unevenly across the scalp rather than thinning uniformly. It results from a combination of genetic and hormonal influences. The relevant gene has two alleles: one for uniform hair growth and a baldness allele for patchy hair growth. The baldness allele is dominant in males and is expressed only in the presence of the high level of testosterone characteristic of men. In men who are either heterozygous or homozygous for the baldness allele, testosterone causes terminal hair to be replaced by vellus hair, beginning on top of the head and later the sides. In women, the baldness allele is recessive. Homozygous dominant and heterozygous women show normal hair distribution; only homozygous recessive women are at risk of pattern baldness. Even then, they exhibit the trait only if their testosterone levels are abnormally high for a woman (for example, because of a tumor of the adrenal gland, a woman’s principal source of testosterone). Such characteristics in which an allele is dominant in one sex and recessive in the other are called sex-influenced traits.

Excessive or undesirable hairiness in areas that are not usually hairy, especially in women and children, is called hirsutism. It tends to run in families and usually results from either masculinizing ovarian tumors or hypersecretion of testosterone by the adrenal cortex. It is often associated with menopause.

Contrary to popular misconceptions, hair and nails do not continue to grow after a person dies, cutting hair does not make it grow faster or thicker, and emotional stress cannot make the hair turn white overnight.

Different causes of hair loss affect the hair follicles in different phases of growth. See below for the different types of hair loss.

Figure 3. Hair structure

Figure 4. Hair follicle

Figure 5. Hair growth cycle

What is male pattern baldness

Male pattern baldness is also known as androgenetic alopecia affects all men to some degree as they grow older. Progressive thinning of the hair on the head eventually leads to baldness. The hair loss usually begins at the temples, with the hairline gradually receding. Subsequently, hair at the crown (back) of the head also starts to get thinner.

Male pattern hair loss affects nearly all men at some point in their lives. It affects different populations at different rates, probably because of genetics. Up to half of male Caucasians will experience some degree of hair loss by age 50, and possibly as many as 80% by the age of 70 years, while other population groups such as Japanese and Chinese men are far less affected.

The severity of male pattern baldness can be classified in several ways. Norwood and Sinclair systems are shown below.

Figure 6. Types of male pattern baldness (Norwood Classification)

Figure 7. Male pattern baldness stages

Male pattern baldness causes

Male pattern baldness is related to your genes and male sex hormones. Testosterone is the most important androgen (male sex hormone) in men and is needed for normal reproductive and sexual function. Testosterone is important for the physical changes that happen during male puberty, such as development of the penis and testes, and for the features typical of adult men such as facial and body hair. In the body, testosterone is converted to dihydrotestosterone (DHT) by an enzyme (5-alpha reductase). Dihydrotestosterone (DHT) acts on different organs in the body including the hair follicles and cells in the prostate.

Normally, in the hair cycle, 90 per cent of the hairs on a man’s scalp are in a growth phase (anagen). The other 10 per cent are mostly in a resting phase (telogen). Up to 100 telogen hairs fall out each day, and are replaced by the growth of new hairs.

Dihydrotestosterone (DHT) is the main hormone responsible for male pattern baldness in genetically susceptible individuals. Dihydrotestosterone (DHT) causes hair loss by inducing a change in the hair follicles. The hairs produced by the follicles affected by dihydrotestosterone (DHT) become progressively smaller until eventually the follicles shrink completely and stop producing hair entirely.

In some families there are genes passed on through the family that make men more likely to have androgenetic alopecia. In men with these genes, the hair follicles are more sensitive to dihydrotestosterone (DHT). This leads to hair follicle miniaturization (where the hairs growing from the follicles become thinner and shorter with each cycle of growth) at a younger age.

Scientists are still investigating why men with male pattern baldness inherit this sensitivity to dihydrotestosterone (DHT), but it causes changes in the hair follicle (called miniaturisation), which results in:

- fewer hairs emerging from each follicle;

- each hair becoming finer;

- the anagen growth phase of each hair gradually becoming shorter, so that each hair exists for a shorter time;

- the telogen hairs are shed faster; and

- the lag time between the end of the resting phase and the next growth phase increases.

Each strand of hair sits in a tiny hole (cavity) in the skin called a follicle. Generally, baldness occurs when the hair follicle shrinks over time, resulting in shorter and finer hair. Eventually, the follicle does not grow new hair.

So the hair becomes progressively shorter and finer, and can eventually stop growing altogether, resulting in baldness. The balding process is gradual and only hair on the scalp is affected. The follicles remain alive, which suggests that it is still possible to grow new hair.

It is your genes that will determine whether or not you will develop this type of hair loss and at what age it starts, as well as how extensive it will be and the pattern that the hair loss will follow. You can inherit male pattern hair loss from your mother or your father (or both).

Male pattern baldness genetics

Male pattern hair loss occurs in men who are genetically predisposed to be more sensitive to the effects of dihydrotestosterone (DHT). Researchers now believe that the condition can be inherited from either side of the family. There is a myth that hair loss is a genetic trait passed down from the mother’s side of the family. Genetics is the cause of male pattern hair loss, but a number of genes are responsible and they probably come from both parents. If there is a close relative with male pattern hair loss there is a higher risk of the condition.

Male pattern baldness prevention

There is no known prevention for male pattern baldness.

Male pattern baldness signs and symptoms

The typical sequence of hair loss in men with male pattern hair loss is loss of hair from the temples (sides of the head), which progresses to loss of hair from the front of the head. The hair loss is gradual and referred to as a receding hairline.

Over time, a bald spot may develop at the back or crown of the head, and, in some men, the entire top of the head may become bald over time, leaving a horseshoe-shaped rim of hair. And even that can be lost in some men.

Hair loss can start as early as puberty, although this is uncommon. Many men start to notice thinning of their hair in their late 20s or early 30s, and about 80 per cent of men are affected to some degree by the age of 70.

Some men find that their hair loss progresses quickly, losing much of their hair within 5 years. However, it is more common for hair loss to progress more slowly, usually over 15 to 25 years.

Male pattern baldness diagnosis

Classic male pattern baldness is usually diagnosed based on the appearance and pattern of the hair loss.

Hair loss may be due to other conditions. This may be true if hair loss occurs in patches, you shed a lot of hair, your hair breaks, or you have hair loss along with redness, scaling, pus, or pain.

A skin biopsy, blood tests, or other procedures may be needed to diagnose other disorders that cause hair loss.

Hair analysis is not accurate for diagnosing hair loss due to nutritional or similar disorders. But it may reveal substances such as arsenic or lead.

Male pattern baldness treatment

Treatment is not necessary if you are comfortable with your appearance. Hair weaving, hairpieces, or change of hairstyle may disguise the hair loss. This is usually the least expensive and safest approach for male baldness.

Current male pattern baldness treatment options include:

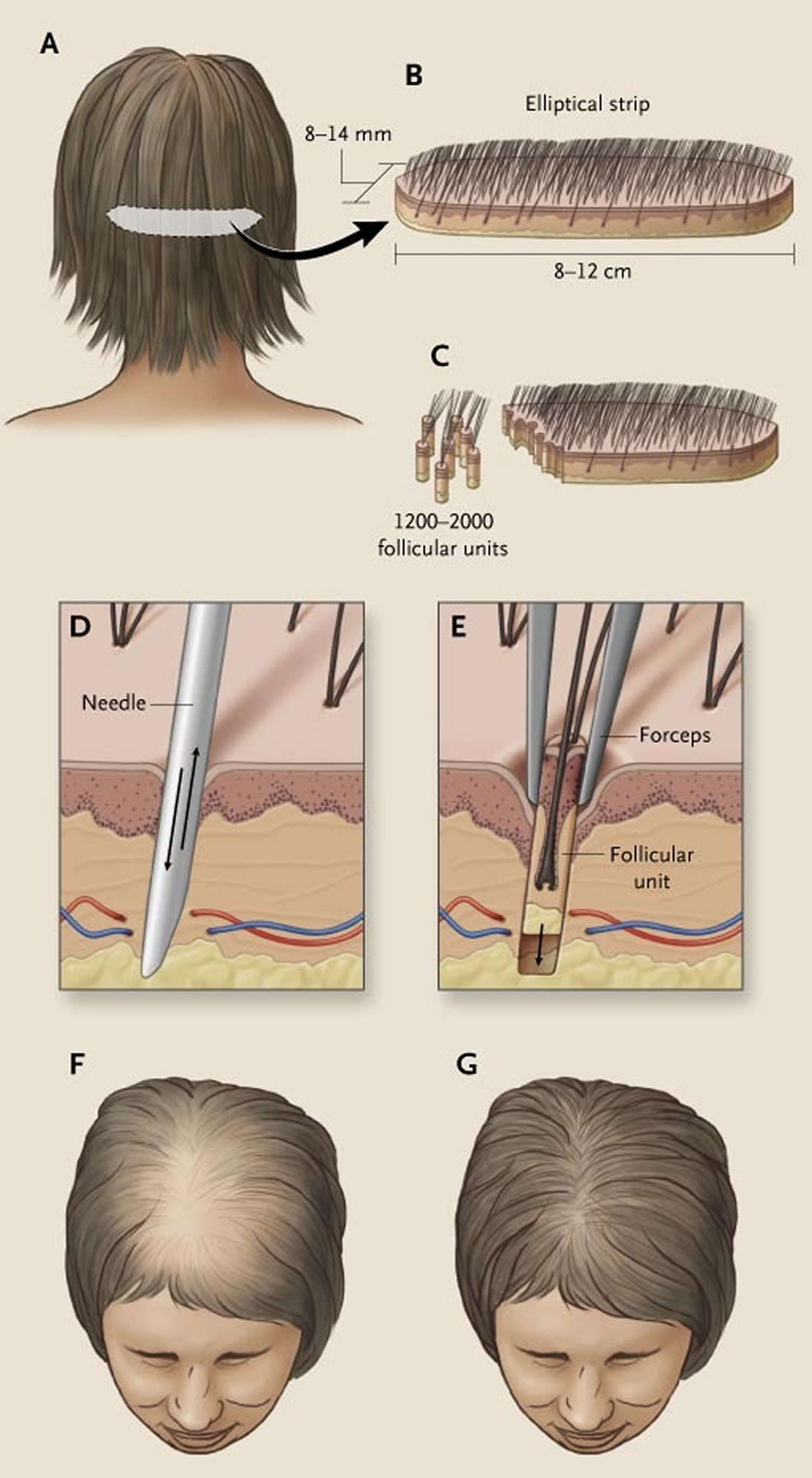

- Hair replacement / transplantation. Hair transplants consist of removing tiny plugs of hair from areas where the hair is continuing to grow and placing them in areas that are balding. This can cause minor scarring and possibly, infection. The procedure usually requires multiple sessions and may be expensive.

- Cosmetics

- Micropigmentation (tattoo) to resemble shaven scalp

- Hairpieces

- Minoxidil (Rogaine) solution, a solution that is applied directly to the scalp to stimulate the hair follicles. It slows hair loss for many men, and some men grow new hair. Hair loss returns when you stop using this medicine.

- Finasteride tablets (Propecia, Proscar) (type II 5-alpha-reductase inhibitor), a pill that interferes with the production of a highly active form of testosterone that is linked to baldness. It slows hair loss. It works slightly better than minoxidil. Hair loss returns when you stop using this medicine.

- Dutasteride (type I and type II 5-alpha-reductase inhibitor). Dutasteride is similar to finasteride, but may be more effective.

Suturing hair pieces to the scalp is not recommended. It can result in scars, infections, and abscess of the scalp. The use of hair implants made of artificial fibers was banned by the FDA because of the high rate of infection.

Topical minoxidil (2% and 5%) and oral finasteride are the only treatments approved by the FDA for treatment of male pattern hair loss in men older than 18 years. Treatment with finasteride can cause decreased libido, impotence, and ejaculation disorders 2. These adverse effects often abate with continued treatment and happen in less than 2 percent of men younger than 40 years 3. Finasteride may also induce depression 4. Minoxidil is available over-the-counter, and it should be applied to the scalp and not the hair. Its mechanism of action is unclear. Some shedding during the first few months of treatment is common. The minoxidil 5% solution has not been shown to be consistently more effective than the 2% solution, and patients using the higher concentration had more adverse effects, including allergic contact dermatitis, dryness, and itching 5. These typically resolve after treatment is discontinued 6.

Several small studies have shown some increased effectiveness with combined minoxidil and finasteride treatment 7, 8. Starting treatment early can help maximize success, and patients can expect to see results after three to six months, although dense regrowth is not likely. Discontinuation of finasteride or minoxidil results in loss of any positive effects on hair growth within 12 and six months, respectively 9. When switching between treatment with finasteride and minoxidil, it is best to overlap treatments for three months to minimize hair loss 10. Additional treatment options are listed in Table 2: Treatment of Hair Loss (Summary & Evidence) below.

A phase 2 randomized placebo-controlled study of dutasteride versus finasteride showed that the effect of dutasteride was dose dependent and 2.5mg of dutasteride was superior to 5mg finasteride in improving scalp hair growth in men between the ages of 21 and 45 years 11. It was also able to produce hair growth earlier than finasteride. This was evidenced by target area hair counts and clinical assessment at 12 and 24 weeks. In addition, a recent randomized, double blind, placebo-controlled study on the efficacy of dutasteride 0.5mg/day in identical twins demonstrated that dutasteride was able to significantly reduce hair loss progression in men with male pattern hair loss 12. A single case report showed improvement of hair loss with dutasteride 0.5mg in a woman who had failed to show any response to finasteride 13, 14.

In one phase 3 study dutasteride 0.5 mg daily showed significantly higher efficacy than placebo based on subject self-assessment and by investigator and panel photographic assessment 15. There was no major difference in adverse events between two groups the treatment and placebo groups. However, this study was limited to only 6 months. Another more recent phase 3 trial found that dutasteride 0.5 mg was statistically superior to finasteride 1 mg and placebo at 24 weeks 16.

There is some evidence that ketoconazole shampoo, an antifungal cortisol inhibitor shampoo, may also be of benefit, perhaps because it is effective in seborrheic dermatitis and dandruff 17, 18. A study compared shampoo containing 2% ketoconazole with unmedicated shampoo among 39 patients with male-pattern androgenetic alopecia 19. Medicated 2% ketoconazole shampoo increased hair density and the size and proportion of hair follicles residing in the anagen phase, both in isolation and in combination with minoxidil 19. Similarly, a 2007 study 20 including six patients with male-pattern androgenetic alopecia found hair regrowth with 2% ketoconazole topical lotion 21. Interestingly, one patient stopped using the lotion and depicted hair loss recurrence three months later, suggesting continual ketoconazole application is required for maintenance of hair regrowth. In addition, the authors found that ketoconazole may promote hair regrowth via both androgen-dependent and androgen-independent mechanisms 21. A 2019 study 22 compared the efficacy of 2% topical ketoconazole in comparison to 2% minoxidil among patients with female-pattern androgenetic alopecia. Whereas a significant difference between baseline and months 4 and 6 was observed among those receiving topical minoxidil, significant improvement with ketoconazole was observed only at month 6, suggesting delayed treatment efficacy with ketoconazole. However, whereas treatment-related side effects were reported among 55% of those receiving minoxidil, side effects were reported in only 10% receiving ketoconazole, and there was no difference in patient satisfaction between the groups 22. These studies highlight the potential therapeutic role of cortisol inhibition on hair regrowth in patients with both male and female-pattern androgenetic alopecia, although additional large, randomized controlled trials are needed to better assess efficacy.

Low-dose oral minoxidil (off label) can increase hair growth on the scalp, but may also result in generalized hypertrichosis and other adverse effects 23.

Low-level laser therapy (LLLT) is of unproven benefit in male pattern balding; the Capillus® laser cap and Hairmax® Lasercomb/Laserband are two low‐level laser therapy (LLLT) devices have been approved by the FDA for the management of androgenetic alopecia 24, 25. Minimal side effects were reported. Small number of participants reported adverse events of acne, mild paresthesia such as burning sensation, dry skin, headache, and itch 26.

Light‐emitting diode (LED) devices. In contrast with low-level laser therapy (LLLT) that delivers a single, collimated wavelength of light, light‐emitting diode (LED) devices may emit a small band of wavelengths. In particular, an all‐LED device that delivers dual dark orange (620 nm) and red light (660 nm) (Revian Red) to promote blood flow, reduce inflammation, and inhibit DHT via 5-alpha-reductase downregulation 27. In a prospective, randomized, double‐blind, controlled study, 18 male pattern hair loss subjects were treated with Revian Red cap vs. 18 male pattern hair loss subjects were treated with a sham light device for 10 min daily for 16 weeks total 28. Preliminary photographic assessments revealed increased mean hair count in the active group as compared to placebo group. Specifically, active group participants demonstrated approximately 26.3 more hairs per cm² compared to the placebo group. Overall, literature has suggested light therapy to be a safe treatment modality for androgenic alopecia (androgenetic alopecia) in both male and female patients when used independently or in combination with topical/oral therapies 26, 29. Light therapy has an excellent side effect profile, and there are no contraindications for use, although caution may be taken when administering in patients with dysplastic lesions on the scalp 30.

Platelet-rich plasma injections are also under investigation 31. Platelet‐rich plasma treatment can be administered alone or in combination with other therapies for androgenetic alopecia, although better results are obtained if platelet‐rich plasma administration is used in association with topical (such as minoxidil) or oral therapies (finasteride) 31. Further studies are required to determine the magnitude of the benefit if any.

Platelet‐rich plasma is generally indicated for patients with early‐stage androgenic alopecia, as intact hair follicles are present and a more significant hair restorative effect can be achieved 32. During the procedure, approximately 10–30 mL of blood are drawn from the patient’s vein and centrifuged for 10 min in order to separate the plasma from red blood cells. The platelet‐rich plasma, containing numerous growth factors, is then injected into the deep dermis or subcutaneous tissue at a volume of 4–8 mL per session. Mild side effects include scalp pain, headache, and burning sensation, but these effects usually subside in 10–15 minutes post‐injection and do not warrant use of topical anesthesia or pain medications 33. Vibration or cool air is typically sufficient to alleviate any significant pain that a patient may feel from the treatment. Patients can resume regular activities immediately after treatment but should avoid strenuous physical activity 24 hour post‐treatment to allow for optimal absorption of platelet‐rich plasma into tissue.

Hausauer and Jones 34 conducted a single center, blinded, randomized controlled trial investigating the efficacy of two platelet‐rich plasma regimens in 40 androgenic alopecia subjects. Participants received either subdermal platelet‐rich plasma injections with 3 monthly sessions and booster 3 months later (group 1) or 2 sessions every 3 months (group 2). Folliscope hair count and shaft caliber, global photography, and patient satisfaction questionnaires were completed at baseline, 3‐month, and 6‐month visits. The authors reported statistically significant increases in hair count and shaft caliber in both groups at 6 months. Importantly, improvements occurred more rapidly and profoundly in group 1, indicating that platelet‐rich plasma injections should be administered first monthly 34. Alves and Grimalt 35 demonstrated significant differences in mean anagen hair and telogen hair count as well as telogen and overall hair density when compared to baseline. In a review of 16 studies comprising a total of 389 patients with androgenic alopecia, the majority demonstrated efficacy in promoting successful hair growth after 3–4 sessions on a monthly basis, followed by quarterly maintenance sessions 36.

Platelet‐rich plasma is not curative for hair loss and must be continued long term for hair sustenance. However, patient satisfaction is typically very high and 60–70% of patients continue to undergo maintenance treatments. Due to the relatively recent introduction of platelet‐rich plasma injections for androgenic alopecia, there are no long‐term studies evaluating its effectiveness. Additionally, it is difficult to compare the efficacy with other remedies due to the lack of standardization in regard to platelet‐rich plasma kits, treatment fractions, and regimens, including the use of newer multi‐needle injectors.

While platelet‐rich plasma injections are considered safe when performed by a trained medical provider, these treatments are not suitable for everyone. Platelet‐rich plasma may not be appropriate for those with a history of bleeding disorders, autoimmune disease, or active infection, or those currently taking an anticoagulant medication. Although the majority of patients seem to tolerate the pain associated with scalp injections, some patients may prefer to avoid it.

Finasteride

Finasteride (also known as Propecia®) is taken as a tablet and works by blocking the conversion of testosterone to DHT. The hair follicles are then not affected by DHT and can grow normally. About two in three men who take finasteride every day get some hair regrowth. One in three men may have no hair regrowth but most of these don’t have any further hair loss. Finasteride has no effect in about one in 100 men.

The usual dose of finasteride is one tablet daily, with regrowth or reduction of further hair loss visible after about 4 months. However, it may take 2 or more years before a noticeable effect is seen. Hair growth is usually greater over the crown than over the front areas of the scalp. Also, the effect of finasteride is only maintained while you continue to take the medicine – if you stop taking the tablets hair loss will resume, so ongoing treatment is needed for long-term benefit. Side-effects are uncommon, but about two in 100 men taking finasteride experience a lower libido (sex drive).

Finasteride (marketed as Proscar®) is taken in higher doses as a treatment for benign prostate enlargement.

Finasteride taken at these higher doses may raise a man’s chance of getting certain types of prostate cancer. However, the much lower dose used for hair loss is not known to have any effect on a man’s chance of developing prostate cancer.

If you have any concerns, speak to your doctor.

Be aware that finasteride does not lead to hair regrowth in all men who try it, although it does stop further hair loss in most men. In order to decide how effective the treatment is for you, it may be a good idea to photograph your scalp before treatment and again after 6-12 months. Finasteride is only available on prescription from your doctor.

Side effects of finasteride

Side effects of finasteride are uncommon and usually mild. Talk to your doctor about the risks of taking finasteride.

A small number of men report a decreased libido (sex drive) and problems with their erections (erectile dysfunction) are recognized side-effects of treatment with finasteride in men 37. Some small differences have been seen in the semen of males who take finasteride, such as low sperm counts 38. Sperm levels improved when the medication was stopped. Taking finasteride may increase the risk that you will develop high-grade prostate cancer (a type of prostate cancer that spreads and grows more quickly than other types of prostate cancer) or male breast cancer 39, 40.

In rare cases, gynecomastia (male breast enlargement) has occurred in men taking finasteride.

Although finasteride is generally well tolerated in a study of 3,200 men, including patients on therapy for up to two years. Recently many reports described adverse effects in men during finasteride treatment, such as sexual dysfunction and mood alteration 41, 42, 43, 44, 45. In addition, it has been also reported that persistent side effects may occur in some androgenetic alopecia patients. This condition, termed post-finasteride syndrome (PFS) represents a constellation of sexual, physical, and neurological symptoms that develop and persist during treatment and/or after finasteride discontinuation 46, 47, 48. Among the reported sexual and physical adverse effects associated with post-finasteride syndrome (PFS) are: loss of libido; erectile dysfunction; ejaculatory disorders; reduction in penis size; penile curvature; reduced sensation; decreased arousal and difficulty in achieving orgasm; gynecomastia; muscle atrophy; fatigue; and severely dry skin. Reported neurological (psychiatric) adverse events include: depression and anxiety; cognitive impairment; and suicidal ideation that are still present despite drug withdrawal 48. Furthermore, several case studies have linked finasteride with male infertility 49, 50, cataract and intraoperative floppy-iris syndrome 51, pseudoporphyria 52 and T cell–mediated acute localized exanthematous pustulosis 53. As a result, regulatory agencies in several countries generated warnings about finasteride (e.g., Swedish Medical Products Agency, the Medicines and Healthcare Products Regulatory Agency of UK and the U.S. Food and Drug Administration) required to include multiple persistent side effects within the finasteride labels 46.

Dutasteride

Dutasteride is the successor to finasteride acting as a second‐generation 5‐alpha‐reductase inhibitor and functioning as a selective competitive inhibitor of type 1 and type 2 isoenzymes of 5‐alpha‐reductase 54. Dutasteride is reported to be three times more potent at inhibiting the type I 5‐alpha‐reductase enzyme and 100 times more potent at inhibiting the type II 5‐alpha‐reductase enzyme than finasteride 55. Dutasteride comes in 2.5 and 5 mg doses, both of which have shown superior efficacy to finasteride 5 mg 11. Due to dutasteride’s large molecular size, it is difficult to formulate and deliver as a topical agent. However, its large size and fat soluble (lipophilic) nature contribute to it remaining on the scalp and preventing absorption into your body. If requested by clinicians, compounding pharmacies may formulate dutasteride topical solutions, although literature is sparse regarding its utility in treating androgenetic alopecia.

Olszewska and Rudnicka 13 reported a case of a female patient with androgenetic alopecia who did not respond to minoxidil and initially benefited from finasteride. Given her persistent androgenetic alopecia, the patient was started on oral dutasteride. After 6 months of treatment, clinical and trichogram assessments revealed significant improvement in hair density 13. Several randomized, double‐blind, placebo‐controlled clinical studies have demonstrated dutasteride’s effectiveness for treating androgenetic alopecia 54, 56. Intradermal (injection into the skin) dutasteride was also reported in order to decrease the systemic side effects. Saceda‐Corralo et al. 57 administered 1 mL intradermal dutasteride 0.01% injections every 3 months for a total of three sessions to six subjects. Trichoscopy assessments revealed increased hair diameter and density, in addition to clinical improvement in androgenetic alopecia. There were no statistically significant differences in serum levels of total and free testosterone, 3 alpha androstanediol glucuronide, and dihydrotestosterone before and after treatment 57. Similar studies injecting dutasteride mesotherapy yielded promising results 58, 59, 60. Overall, oral dutasteride appears to be superior to the intradermal route. However, more studies are warranted 56.

Overall, dutasteride has shown superior efficacy both in blocking DHT and promoting hair growth compared to finasteride. In a study of 399 patients, dutasteride was found to block 98.4% of DHT, while finasteride blocked about 70% 55. In another study of 416 men between 21 and 45 years of age, dutasteride was found to produce better hair count results than finasteride over a period of 12–24 weeks 11. Despite the greater efficacy demonstrated by dutasteride, finasteride is still likely to be prescribed more often as a first‐line agent in treating male pattern baldness due to FDA approval and insurance coverage.

Side effects of dutasteride

Similar to finasteride, the side effects of oral dutasteride include decreased sex drive (libido), erectile dysfunction, and ejaculatory dysfunction 56.

Topical Minoxidil

Minoxidil (also known as Rogaine®, Hair a-gain®, Hair Retreva®) is a lotion that is rubbed onto the head. Topical minoxidil is one of the only three FDA‐approved treatments for male and female pattern hair loss. Minoxidil is available in both 2% and 5% solutions and in foam preparation, so clinicians and patients have flexibility to select their preferred strength and formulation. The 5% solution has demonstrated greater efficacy than the 2% solution, and the 5% foam has shown equivalency to the 2% and 5% solutions depending on frequency of use 61, 62. Minoxidil foam is often more convenient to use, as it dries quicker and has less tendency to spread to the peripheral areas. Some patients report an unpleasant residue after applying the foam, in which case a solution formulation may be preferred. Minoxidil must be applied once or twice daily for full effect. If used properly, patients can expect to see hair growth within 4–8 months which stabilizes after 12–18 months 63. If a patient terminates treatment, progressive hair loss can be expected within 12–24 weeks 64.

Topical minoxidil was approved specifically for androgenic alopecia in 1988 as a first‐line treatment for men with mild‐to‐moderate androgenic alopecia 65, 66. About half of the men using minoxidil have a delay in further balding 67. About 15 in 100 men have hair regrowth, while hair loss continues in about one in three users. Minoxidil needs to be rubbed onto the scalp twice daily, and used for four months before results can be seen. There may actually be some hair loss at the beginning of treatment, as hair follicles in the resting phase are stimulated to move to the growth phase. Treatment needs to be ongoing for hair growth to continue; any hair that has regrown may fall out two months after treatment is stopped.

In a 1 year study of 904 males with androgenetic alopecia, 62% of the patients exhibited a significant decrease in the affected region of the scalp when treated with 5% topical minoxidil twice daily and 84.3% of patients reported hair regrowth of varying degrees 68. The 2% and 5% Minoxidil solutions have elicited a 70% greater improvement in mean hair density compared with placebo after 16 and 26 week treatment periods 69, 70, 71. In a randomized control trial of 278 patients treated with minoxidil, 45% demonstrated more hair regrowth when treated with 5% solution vs. 2% by 48 weeks of treatment 69.

Be aware that minoxidil is not effective for all men, and the amount of hair regrowth will vary among people. Some men experience hair regrowth while in others hair loss is just slowed down. If there is no noticeable effect after 6 months, it’s recommended that treatment is stopped.

Side effects associated with minoxidil

The most common side effects of minoxidil include a dry, red and itchy scalp. Higher-strength solutions are more likely to cause scalp irritation and excessive facial hair growth 72.

Bear in mind that minoxidil is also used in tablet form as a prescription medicine to treat high blood pressure, and there is a small chance that minoxidil solution could possibly affect your blood pressure and heart function. For this reason, minoxidil is generally only recommended for people who do not have heart or blood pressure problems.

Always follow the directions on the product, making sure you use minoxidil only when your scalp and hair are completely dry. Wash your hands after use.

Oral minoxidil

Although not FDA‐approved and not nearly as popular as finasteride, multiple studies were conducted to evaluate oral minoxidil for treating both male and female patients with androgenetic alopecia. Oral minoxidil is available as a 2.5 mg tablet, and it can be cut in halves or quarters to achieve optimal safe dosing for the treatment of androgenetic alopecia. Sinclair first reported the combination of oral minoxidil 0.25 mg and spironolactone 25 mg to be a safe and effective option in managing female pattern hair loss 73.

Several retrospective case series reported oral minoxidil to be an effective treatment for female androgenetic alopecia with favorable side effects 74, 75. Studies suggested that optimal safe doses range between 0.625 mg and 1.25 mg daily 76. Oral minoxidil has also shown equivalent effectiveness in women compared to the 5% topical formulation 77. Jimenez‐Cauhe et al. 23 conducted a retrospective review of 41 men diagnosed with androgenetic alopecia undergoing oral minoxidil 5 mg daily treatment. Side effects were detected in about 30% of the participants, but they were all tolerable 23. Another prospective study 78 using a 5 mg once daily regimen showed 100% improvement at week 12 and 24 with 43% patients achieving excellent improvement. Pirmez et al. 79 suggested that very low dose oral minoxidil (0.25 mg once daily) may be less effective in treating moderate androgenetic alopecia and higher dosage might be needed. However, the sample size was small.

Side effects oral minoxidil

Although it may be more convenient for patients to take the oral form of minoxidil, its systemic side effects such as increased heart rate, weight gain, hirsutism, hypertrichosis, and lower extremity edema make it unfavorable compared to topical minoxidil as a first‐line treatment 78. In a recent study of 1404 subjects 80, the most common side effect was noted to be hypertrichosis in about 15% of patients and the incidence of systemic adverse effects was noted in 1.7% of patients. Oral minoxidil’s side effects, however, are typically dose‐dependent and reversible with discontinuation of the drug. Rare side effects include pericardial effusion, congestive heart failure, and allergic reactions 78.

Scalp massage

Developing hair follicles are surrounded by deep dermal vascular plexuses. Associated blood vessels function to supply nutrients to the developing hair follicle and foster waste elimination. As such, proper blood supply is necessary for effective hair follicle growth, further exemplified by the angiogenic properties of the anagen phase 81. A 2016 study 82 assessed the effect of a 4-minute standardized daily scalp massage for 24 weeks among nine healthy men. Authors found scalp massage to increase hair thickness, upregulate 2655 genes, and downregulate 2823 genes; hair cycle-related genes including NOGGIN, BMP4, SMAD4, and IL6ST were among those upregulated, and hair-loss related IL6 was among those downregulated 82. The authors thereby concluded that a standardized scalp massage and subsequent dermal papilla cellular stretching can increase hair thickness, mediated by changes in gene expression in dermal papilla cells 82.

In addition, of 327 survey respondents attempting standardized scalp massages following demonstration video, 68.9% reported hair loss stabilization or regrowth 83. Positive associations existed between self-reported hair changes and estimated daily minutes, months, and total standardized scalp massage effort. This study 83 is limited based on recall bias and reliance on patient adherence and technique, although it suggests promising therapeutic potential for standardized scalp massage, which functions to increase blood flow.

Low-level laser (light) therapy

Low-level laser (light) therapy refers to therapeutic exposure to low levels of red and near infrared light 84. Studies have demonstrated increased hair growth in mice with chemotherapy-induced alopecia and alopecia areata, in addition to both men and women human subjects. Proposed mechanisms of efficacy include stimulation of epidermal stem cells residing in the hair follicle bulge and promoting increased telogen to anagen phase transition 85. Interestingly, while minoxidil and finasteride are the only FDA-approved drugs for androgenetic alopecia, a 2017 study 29 found comparable efficacy among patients receiving low-level light therapy versus topical minoxidil among patients with female-pattern androgenetic alopecia. In addition, combination therapy resulted in the greatest patient satisfaction and lowest Ludwig classification scores of androgenetic alopecia.

A meta-analysis including eleven double-blinded randomized controlled trials found a significant increase in hair density among patients with androgenetic alopecia receiving low level light therapy compared to those in the placebo-controlled group 86. Low level light therapy was effective for men and women. Furthermore, a subgroup analysis observed a more significant increase in hair growth in those receiving low-frequency therapy than receiving high-frequency therapy 86. Despite the limitation of the heterogeneity of included trials, these results suggest low level laser (light) therapy to be a promising therapeutic strategy for androgenetic alopecia 86, although further research is necessary to determine the optimal wavelength and dosimetric parameters for hair growth 85.

Prostaglandins

Latanoprost is a prostaglandin F2 agonist and has been shown to have a direct effect on hair growth and pigmentation in eyelashes and hair around the eyes 87. Clinically used to treat glaucoma, latanoprost was found to affect the hair follicles in the telogen phase and cause them to move to the anagen phase; this was supported by the increased number and length of eyelashes seen in patients using latanoprost 87. Subsequently, the application of latanoprost for patients experiencing alopecia was assessed in clinical studies. One conducted in 2012 studied the effects of 0.1% latanoprost solution applied to the scalp for 24 weeks 88. Participants included 16 males with mild androgenetic alopecia and were instructed to apply placebo on one area of the scalp and the treatment on another area. The results indicated that the area of scalp receiving latanoprost had significantly improved hair density compared to placebo 88.

Another prostaglandin known as bimatoprost, a prostamide-F2 analog, was also found to have a positive effect on hair growth in human and mouse models 89. A study conducted in 2013 also found that bimatoprost, in both humans and mice, stimulated the anagen phase of hair follicles prompting an increase in hair length, i.e., promoting hair growth 89. The study also confirmed the presence of prostanoid receptors in human scalp hair follicles in vivo, opening the strong possibility that scalp follicles can also respond to bimatoprost in a similar fashion 89.

It is important to note, however, that not all prostaglandins induce hair growth 90. In a study analyzing individuals with androgenetic alopecia with a bald scalp versus a haired scalp, it was discovered that there was an elevated level of prostaglandin D2 synthase at the mRNA and protein levels in bald individuals 90. They were also found to have an elevated level of prostaglandin D2 (PGD2). When analyzing the level of prostaglandin D2 synthase presence through the various phases of hair follicular growth, it was found that the level steadily increased throughout the anagen phase with a peak in late anagen, at the time of transition to the catagen (breakdown) phase. Therefore, the study concluded that prostaglandin D2 (PGD2)’s hair loss effect represents a counterbalance to PGE2 and PGF2’s hair growth effects. In conclusion, prostaglandins are a promising treatment option for alopecia that require larger clinical studies; however, clinicians should be aware of which one to recommend for hair growth, as not all prostaglandins are alike 91.

Platelet rich plasma

Platelet rich plasma (PRP) has conventionally been used to supplement a patient’s endogenous platelet supply to promote increased healing 91. However, its prominent supply of growth factors has prompted assessment of platelet rich plasma for alopecia. Growth factors promote hair growth and increase the telogen to anagen transition. For example, a mice study found the fibroblast growth factor (FGF) induced the anagen phase and subsequently promoted hair growth 92. Growth factors prominently included in platelet rich plasma include platelet-derived growth factor (PDGF), transforming growth factor β (TGF-β), vascular endothelial growth factor (VEGF), epidermal growth factor (EGF), insulin-like growth factor (IGF) and fibroblast growth factor (FGF) 93.

The growth factors of platelet-rich plasma stimulate the development of new follicles and neovascularization 94. Three meta-analyses have assessed the efficacy of platelet rich plasma injections compared to placebo control on the number of hairs per cm2 among patients with androgenetic alopecia. One meta-analysis involving 177 patients found a mean improvement of platelet rich plasma treatment compared to placebo of 17.9 95; a second meta-analysis with 262 androgenetic alopecia patients observed a mean difference of 38.8 96; and a third meta-analysis including studies with parallel or half-head design found a mean difference of 30.4 97.

Despite the efficacious results described by each meta-analysis for the use in androgenetic alopecia, gender differences have been observed. A 2020 meta-analysis 98 found that while platelet rich plasma significantly increased hair density and hair diameter from baseline in men, platelet rich plasma only increased hair diameter in women, in the absence of significantly increased hair density. Furthermore, hair density in men was only significantly increased by a double spin method, in contrast to a single spin method 98. The authors conclude that platelet rich plasma effectiveness may be improved via higher platelet concentrations 98. Ultimately, platelet rich plasma injections appear to have clinical efficacy in early studies although with slightly different effects in men vs. women. Future research is necessary to establish the optimal treatment protocol for both men and women with androgenetic alopecia. Also, the role of diet in the days prior to collection of the platelet rich plasma has not been assessed in conjunction with hair, although diet influences the quality of the platelet rich plasma 99.

Hair transplantation

Hair transplant surgery is an option for men with hair loss that has not responded to other treatments. Hair transplantation involves taking tiny clusters, or plugs of hair (each containing up to 4 hairs) from areas where it continues to grow (usually the back of the head) and inserting them in bald or thinning areas. The procedures used to transplant hair are called micrografting or follicular unit transplantation. They can be expensive and painful and transplant sessions may be needed to achieve the desired effect and this can be expensive. Side effects such as skin infection and minor scarring are possible. However, results are usually good and are permanent. Choosing a surgeon with experience in this operation is recommended.

Procedures that involve transplanting body hair to the scalp or implanting artificial hair fibers may be used in some cases, although there is a higher rate of complications with artificial hair implants.

Talk to your doctor about whether these procedures would be suitable for you and about the risks and benefits of these treatments. Your doctor should be able to refer you to a dermatologist or hair transplant surgeon if hair transplant surgery is likely to be a suitable treatment for you.

Cosmetic treatments

Cosmetic treatment options include the following.

- Wearing a wig, hairpiece or toupee. Synthetic and real hair wigs are available.

- A special type of tattooing called scalp micropigmentation or dermatography can give the appearance of a shaved head of hair or thicker hair.

- Coloring the scalp with a camouflage dye may be recommended in some cases where the hair is thinning.

- The use of hair thickening fibers, such as natural keratin fiber, is a treatment that is inexpensive. It involves applying tiny, microfiber ‘hairs’ that bond to existing hair through static electricity to give the appearance of thicker hair.

Talk to your doctor about these options before deciding which, if any, may be suitable for you.

Unproven treatments for hair loss

Remedies for hair loss which have not been shown or proven to be effective include:

- nutritional supplements;

- platelet-rich plasma injections – sometimes known as PRP rejuvenation;

- acupuncture;

- scalp massage; and

- laser treatment.

Discuss with your doctor any treatments that you are interested in trying. It’s important to discuss the risks and benefits before opting for any hair loss treatment options.

If you consult a hair loss clinic or alternative medicine practitioner about treatments for hair loss, make sure you understand exactly what treatments they offer and whether there is any proven scientific evidence for their effectiveness.

It’s always a good idea to check with your doctor before using any treatment, to avoid unwanted effects and spending time or money on a treatment that is unlikely to help.

What is female pattern baldness

Female pattern baldness is also called female pattern hair loss or androgenetic alopecia in women, is a term used to describe hair loss and thinning in women. In female pattern baldness (androgenetic alopecia female), there is diffuse thinning of hair on the scalp due to increased hair shedding or a reduction in hair volume, or both. Female pattern baldness is a term used to describe genetic hair thinning in females. Female pattern baldness can affect women of any age after the onset of puberty but is more common after menopause 100. It is normal to lose up to 50-100 hairs a day. Increased hair shedding is a feature to female pattern baldness (androgenetic alopecia female). The hair loss process is not constant and usually occurs in fits and bursts. It is not uncommon to have accelerated phases of hair loss for 3–6 months, followed by periods of stability lasting 6–18 months. Without medication, it tends to progress in severity over the next few decades of life. Around 40% of women by age 50 show signs of hair loss and less than 45% of women reach the age of 80 with a full head of hair 101. Unlike other areas of the body, hairs on the scalp grow in tufts of 3–4. In androgenetic alopecia, the tufts progressively lose hairs. Eventually, when all the hairs in the tuft are gone, bald scalp appears between the hairs.

Another condition called chronic telogen effluvium also presents with increased hair shedding and is often confused with female pattern baldness (androgenetic alopecia female). It is important to differentiate between these conditions as management for both conditions differ.

Female pattern baldness is a similar condition to male pattern baldness, but the hair loss and thinning follow a different pattern. Unlike with male pattern baldness, which starts with a receding hair line, hair loss in women occurs across the top of the head, the central portion of the scalp, sparing the frontal hairline, and is characterized by a wider midline part on the crown than on the occipital scalp (Figure 8). The hair usually thins across the whole scalp. A receding hairline or a bald patch on the top of the head is rare, although this can happen.

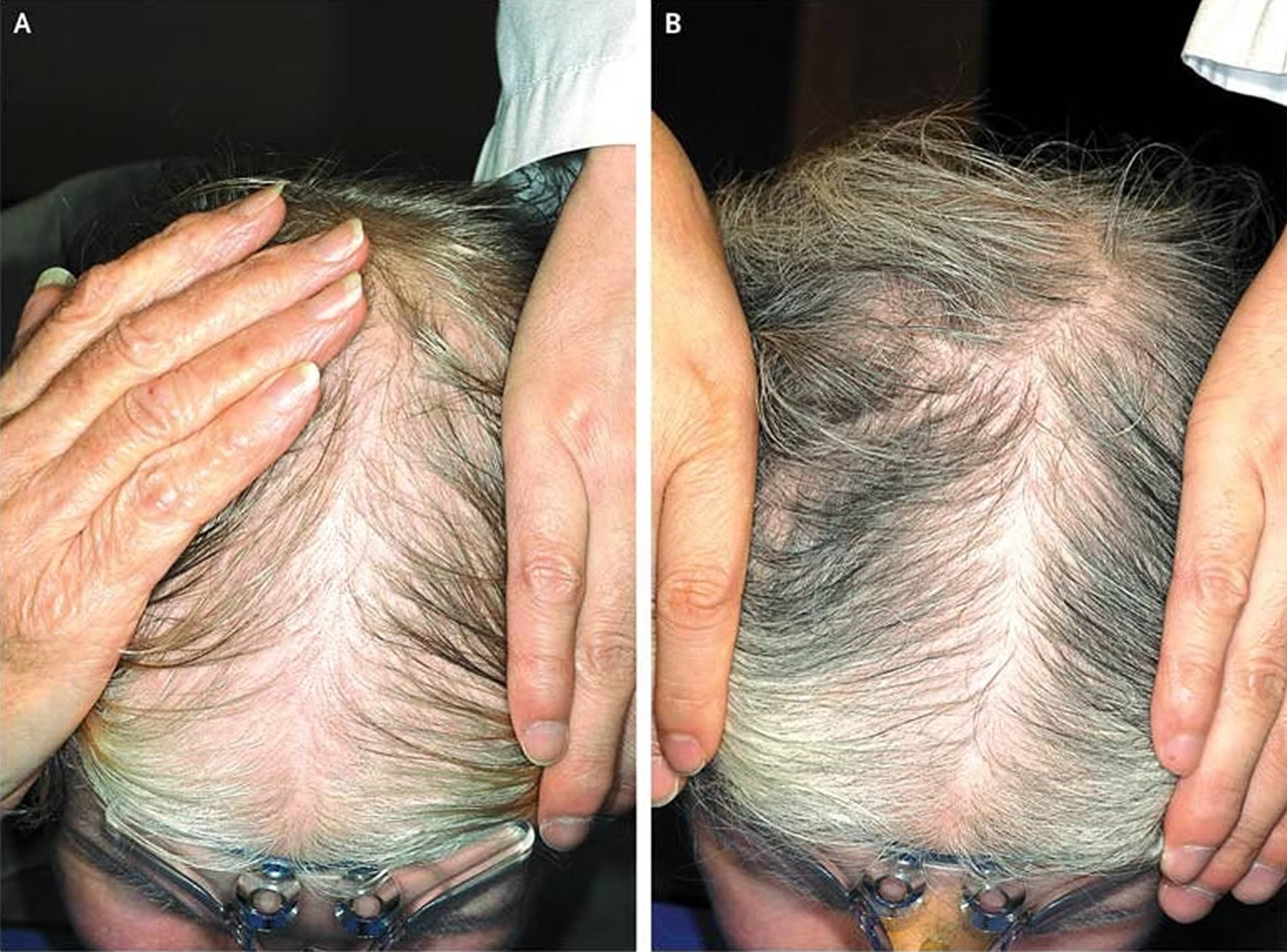

In some women, hair thinning over the side area of the scalp also occurs. The severity of hair loss is staged according to the Ludwig classification (Figure 9), in which increasing stages (I to III) correspond to increasing widths of the midline part 102. Women can use the hair shedding guide below to define whether hair shedding is normal or excessive. If hair thinning is more evident in the frontal portion of the scalp, the part may resemble a fir tree in what is known as a “Christmas tree pattern” behind the frontal hair line (Figure 10). This pattern is referred to as “frontal accentuation” 100.

It is very uncommon for women to bald following the male pattern unless there is excessive production of androgens in the body. Male patterns of hair loss may be associated with hyperandrogenism, but the majority of women with female-pattern hair loss have normal serum androgen levels 103. One study 104 showed a prevalence of biochemical hyperandrogenemia of 38.5% among women with moderate-to-severe alopecia; approximately one quarter of these women had no other signs of hyperandrogenemia, such as hirsutism or menstrual disturbances.

The hair loss associated with female pattern baldness, although permanent, requires no treatment if you are comfortable with your appearance.

There is no known prevention for hair loss; shampooing and other hair products have no adverse effects other than harsh products or practices that may damage the hair shaft, causing breakage.

Many studies have shown that hair loss is not merely a cosmetic issue, but it also causes significant psychological distress. Compared to unaffected women, those affected have a more negative body image and are less able to cope with daily functioning. Hair loss can be associated with low self-esteem, depression, introversion, and feelings of unattractiveness. It is especially hard to live in a society that places great value on youthful appearance and attractiveness.

Baseline photographs (typically of the midline part) should be taken and used on subsequent visits for comparison. To assess hair shedding, women should choose which of the six photographs of hair bundles best represents how much hair they shed on an average day.

Doctors can use the hair shedding scale to score hair loss at each patient visit to assess response to treatment. It can also be used in clinical trials to assess new treatments for excess hair shedding.

Therapies for androgenetic alopecia women include topical minoxidil (2% & 5%), antiandrogen medication and hair transplantation in selected patients. Six months to 1 year of treatment may be required before there is considerable improvement.

Figure 8. Female pattern baldness

Figure 9. Female pattern baldness stages

Figure 10. Female pattern hair loss with frontal accentuation (Christmas tree pattern)

Footnote: Panel A shows hair loss before topical 5% Minoxidil treatment, and Panel B shows regrowth after 6 months of treatment.

Female pattern baldness causes

Genetics usually plays a part in the development of female pattern baldness. You can inherit the genes that cause female pattern baldness from one or both of your parents. However, some women with female pattern baldness do not have any paternal or maternal family history of baldness. It’s also possible that hormones contribute to female pattern hair loss, although the exact role that androgens play in women is uncertain.

Female pattern baldness is more common after menopause, suggesting that changes in the levels of female hormones (estrogens) may also be involved.

Female pattern baldness is different from alopecia areata, which is an auto-immune disease resulting in hair loss from the scalp and other parts of the body.

At the scalp level, hair follicles are more sensitive to the effects of androgen hormones that are required to drive female pattern baldness. This does not imply any underlying hormonal abnormalities. In fact, the vast majority of women with female pattern baldness have normal hormonal profiles. Routine hormonal testing is not required but may be recommended by your doctor if you have other signs of androgen excess such as acne, irregular periods, excessive body hair, etc.

Female pattern baldness is not caused by changes to your diet, infections or hair styling practices.

In a small number of women with female pattern hair loss have a higher than normal concentration of male hormones in their bodies. These women may lose hair in a similar pattern to men with male pattern hair loss and often have additional symptoms related to this excess of androgens, such as:

- hirsutism (too much hair on the face or body);

- severe acne; or

- irregular periods.

If you have hair loss plus these additional features, your doctor may want to rule out the possibility that a condition such as polycystic ovary syndrome (PCOS) may be causing (or contributing to) your hair loss. Rarely, this combination of symptoms may indicate a tumor that is secreting male hormones.

Female pattern baldness prevention

There is no known prevention for female pattern baldness.

Female pattern baldness signs and symptoms

Hair thinning is different from that of male pattern baldness. In female pattern baldness:

- Hair thins mainly on the top and crown of the scalp. It usually starts with a widening through the center hair part.

- The front hairline remains unaffected except for normal recession, which happens to everyone as time passes.

- The hair loss rarely progresses to total or near total baldness, as it may in men.

- If the cause is increased androgens, hair on the head is thinner while hair on the face is coarser.

Itching or skin sores on the scalp are generally not seen.

Female pattern baldness diagnosis

Talk to your doctor if your hair is thinning. Your doctor will examine your hair and scalp, and might refer you to a dermatologist, a doctor who specializes in skin problems. Your doctor can often diagnose female pattern baldness on clinical grounds without a scalp biopsy. However, your doctor may suggest a biopsy to rule out other hair loss conditions that can mimic female pattern baldness.

Female pattern baldness is usually diagnosed based on:

- Ruling out other causes of hair loss.

- The appearance and pattern of hair loss.

- Your medical history.

If you have acne, irregular periods or a lot of body hair, your doctor might recommend a test to check your hormones, or to rule out polycystic ovarian syndrome (PCOS).

They might also recommend removing a tiny piece of skin from your scalp (skin biopsy) to test for hair loss conditions such as alopecia areata.

Your health care provider will examine you for other signs of too much male hormone (androgen), such as:

- Abnormal new hair growth, such as on the face or between the belly button and pubic area

- Changes in menstrual periods and enlargement of the clitoris

- New acne

A skin biopsy of the scalp or blood tests may be used to diagnose skin disorders that cause hair loss.

Looking at the hair with a dermoscope or under a microscope may be done to check for problems with the structure of the hair shaft itself.

Female pattern baldness treatment

The main aim of treatment is to slow down or stop your hair loss. Treatment might also stimulate hair growth, but this kind of treatment works better for some women than others.

Medicines

The only medicine approved by the United States Food and Drug Administration (FDA) to treat female pattern baldness is minoxidil:

- It is applied to the scalp.

- For women, the 2% solution or 5% foam is recommended.

- Minoxidil may help hair grow in about 1 in 4 or 5 of women. In most women, it may slow or stop hair loss.

- You must continue to use this medicine for a long time. Hair loss starts again when you stop using it. Also, the hair that it helps grow will fall out.

Minoxidil 2% is the only treatment approved by the U.S. Food and Drug Administration (FDA) for treating female pattern hair loss in women older than 18 years. Topical minoxidil; the 2% preparation recommended for women is available over the counter. This may help hair to grow in a quarter of the women using it, and it will stop or slow hair loss in the majority of users. A Cochrane systematic review published in 2012 105 concluded that minoxidil solution was effective for female pattern hair loss. This updated 2016 Cochrane review found that minoxidil is more effective than placebo for female pattern hair loss or female androgenic alopecia 106. Minoxidil is available as 2% and 5% solutions; the stronger preparation is more likely to irritate and may cause undesirable hair growth unintentionally on areas other than the scalp. Furthermore, the updated 2016 Cochrane review found no difference in effect between the minoxidil 2% and 5% for female pattern hair loss 106.

If minoxidil does not work, your doctor may recommend other medicines, such as spironolactone, cimetidine, birth control pills, ketoconazole, among others. Your doctor can tell you more about these if needed.

There is not enough evidence to show that laser treatments, platelet-rich plasma injections, ‘hair tonics’ and nutritional supplements will stimulate hair growth. The true value of commercially available hair tonics and nutritional supplements claiming to treat female pattern baldness is also dubious.

Hormonal treatment, i.e. anti-androgen medicines are oral medications that block the effects of androgens (e.g. spironolactone, cyproterone acetate, finasteride and flutamide) is also often tried. These medicines help stop hair loss and may also stimulate hair regrowth. Spironolactone has been shown to stop the loss of hair in 90 per cent women with androgenetic alopecia. In addition, partial hair regrowth occurs in almost half of treated women. The effects of treatment generally only last while you continue to take the medicine – stopping the medicine will mean that your hair loss will return. Spironolactone and cyproterone acetate should not be taken during pregnancy. Effective contraception must be used while you are being treated with these medicines, as it can affect a developing baby. These medicines should also not be taken if you are breast feeding.

A hyperandrogenic state may limit the success of treatment with minoxidil 107 and, in these women, spironolactone (Aldactone) 100 to 200 mg daily may slow the rate of hair loss 108. Women with evidence of a hyperandrogenic state requesting combined oral contraceptives would benefit from using antiandrogenic progesterones, such as drospirenone 109. Finasteride (Propecia) is ineffective in postmenopausal women with female pattern hair loss 110. Finasteride, spironolactone, and cyproterone should not be used in women of childbearing potential.

A combination of low dose oral minoxidil (eg, 2.5 mg daily) and spironolactone (25 mg daily) has been shown to significantly improve hair growth, reduce shedding and improve hair density.

Once started, treatment needs to continue for at least six months before the benefits can be assessed, and it is important not to stop treatment without discussing it with your doctor first. Long term treatment is usually necessary to sustain the benefits.

It takes about 4 months of using minoxidil to see any obvious effect. You might have some hair loss for the first couple of weeks as hair follicles in the resting phase are stimulated to move to the growth phase. You need to keep using minoxidil to maintain its effect – once you stop treatment the scalp will return to its previous state of hair loss within 3 to 4 months. Also, be aware that minoxidil is not effective for all women, and the amount of hair regrowth will vary among women. Some women experience hair regrowth while in others hair loss is just slowed down. If there is no noticeable effect after 6 months, it’s recommended that treatment is stopped.

Always carefully follow the directions for use, making sure you use minoxidil only when your scalp and hair are completely dry. Take care when applying minoxidil near the forehead and temples to avoid unwanted excessive hair growth. Wash your hands after use.

The most common side effects of minoxidil include a dry, red and itchy scalp. Higher-strength solutions are more likely to cause scalp irritation.

Bear in mind that minoxidil is also used in tablet form as a prescription medicine to treat high blood pressure, and there is a small chance that minoxidil solution could possibly affect your blood pressure and heart function. For this reason, minoxidil is generally only recommended for people who do not have heart or blood pressure problems.

Minoxidil should not be used if you are pregnant or breast feeding.

Topical Minoxidil

Minoxidil is a medicated solution you apply to the scalp to help stop hair loss. Topical 2% minoxidil solution is approved by the Food and Drug Administration (FDA) for women with thinning hair due to female-pattern hair loss. It may also stimulate hair regrowth in some women. Brand names include Regaine for Women and Hair A-Gain. Minoxidil for hair loss is available over-the-counter from pharmacies – you don’t need a prescription.

It takes about 4 months of using minoxidil to see any obvious effect. You might have some hair loss for the first couple of weeks as hair follicles in the resting phase are stimulated to move to the growth phase.

You need to keep using minoxidil to maintain its effect – once you stop treatment the scalp will return to its previous state of hair loss within 3 to 4 months. Also, be aware that minoxidil is not effective for all women, and the amount of hair regrowth will vary among women. Some women experience hair regrowth while in others hair loss is just slowed down. If there is no noticeable effect after 6 months, it’s recommended that treatment is stopped.

Always carefully follow the directions for use, making sure you use minoxidil only when your scalp and hair are completely dry. Take care when applying minoxidil near the forehead and temples to avoid unwanted excessive hair growth. Wash your hands after use.

In a double-blind, placebo-controlled trial, 2% minoxidil used twice daily resulted in minimal hair regrowth in 50% of women and moderate hair regrowth in 13% of women after 32 weeks of treatment, as compared with rates of 33% and 6%, respectively, in the placebo group 111. Efficacy can be assessed definitively after 6 to 12 months of treatment. Side effects of topical minoxidil therapy include contact dermatitis (attributed in many cases to irritation from propylene glycol in the solution) and symmetric facial hypertrichosis manifested as fine hairs on the cheeks or forehead in up to 7% of women. Hypertrichosis disappears within 4 months after discontinuation of the drug. Minoxidil should not be used in pregnant or nursing women.

The use of 5% minoxidil may be considered in women who do not have a response to the 2% formulation or who want more aggressive management 112. A double-blind, randomized trial comparing a 5% minoxidil solution with a 2% minoxidil solution used twice daily in women with mild-to-moderate female-pattern hair loss showed no significant difference between the two solutions with respect to investigator assessments of efficacy, but it showed significantly greater patient satisfaction with the 5% preparation 112. However, the incidences of hypertrichosis (excessive hair growth) and contact dermatitis were higher with the 5% solution than with the 2% solution. A new 5% minoxidil foam formulation that contains no propylene glycol appears to be much less likely to cause contact dermatitis than topical minoxidil solution. Although they are prescribed by many dermatologists in practice, neither the 5% minoxidil solution nor the foam preparation is FDA-approved for use in women 113.

Side effects associated with minoxidil

The most common side effects of minoxidil include a dry, red and itchy scalp. Higher-strength solutions are more likely to cause scalp irritation.

Bear in mind that minoxidil is also used in tablet form as a prescription medicine to treat high blood pressure, and there is a small chance that minoxidil solution could possibly affect your blood pressure and heart function. For this reason, minoxidil is generally only recommended for people who do not have heart or blood pressure problems.

Minoxidil should not be used if you are pregnant or breast feeding.

Oral Minoxidil

Although not FDA‐approved and not nearly as popular as topical minoxidil, multiple studies were conducted to evaluate oral minoxidil for treating both male and female patients with androgenetic alopecia. Oral minoxidil is available as a 2.5 mg tablet, and it can be cut in halves or quarters to achieve optimal safe dosing for the treatment of androgenetic alopecia. Sinclair first reported the combination of oral minoxidil 0.25 mg and spironolactone 25 mg to be a safe and effective option in managing female pattern hair loss 73.

Several retrospective case series reported oral minoxidil to be an effective treatment for female androgenetic alopecia with favorable side effects 74, 75. Studies suggested that optimal safe doses range between 0.625 mg and 1.25 mg daily 76. Oral minoxidil has also shown equivalent effectiveness in women compared to the 5% topical formulation 77. Jimenez‐Cauhe et al. 23 conducted a retrospective review of 41 men diagnosed with androgenetic alopecia undergoing oral minoxidil 5 mg daily treatment. Side effects were detected in about 30% of the participants, but they were all tolerable 23. Another prospective study 78 using a 5 mg once daily regimen showed 100% improvement at week 12 and 24 with 43% patients achieving excellent improvement. Pirmez et al. 79 suggested that very low dose oral minoxidil (0.25 mg once daily) may be less effective in treating moderate androgenetic alopecia and higher dosage might be needed. However, the sample size was small.

Side effects oral minoxidil

Although it may be more convenient for patients to take the oral form of minoxidil, its systemic side effects such as increased heart rate, weight gain, hirsutism, hypertrichosis, and lower extremity edema make it unfavorable compared to topical minoxidil as a first‐line treatment 78. In a recent study of 1404 subjects 80, the most common side effect was noted to be hypertrichosis in about 15% of patients and the incidence of systemic adverse effects was noted in 1.7% of patients. Oral minoxidil’s side effects, however, are typically dose‐dependent and reversible with discontinuation of the drug. Rare side effects include pericardial effusion, congestive heart failure, and allergic reactions 78.

Anti-androgen medicines

Antiandrogen agents (including the androgen-receptor blockers spironolactone, cyproterone acetate, and flutamide and the 5α-reductase inhibitor finasteride) and oral contraceptives are not commonly used to treat female-pattern hair loss in North America, but they are used more commonly in Europe 113. None of these agents are FDA-approved for female-pattern hair loss. Cyproterone acetate is not approved in the United States, and neither flutamide nor finasteride is approved for any indication in women, although finasteride is approved for the treatment of hair loss in men.

Spironolactone and cyproterone acetate (brand names include Androcur, Cyprone and Cyprostat) are anti-androgen medicines that may be prescribed to treat female pattern hair loss.

These medicines help stop hair loss and may also stimulate hair regrowth. Spironolactone has been shown to stop the loss of hair in 90 per cent women with androgenetic alopecia. In addition, partial hair regrowth occurs in almost half of treated women.

The effects of treatment generally only last while you continue to take the medicine – stopping the medicine will mean that your hair loss will return.