Health Benefits of Pomegranate

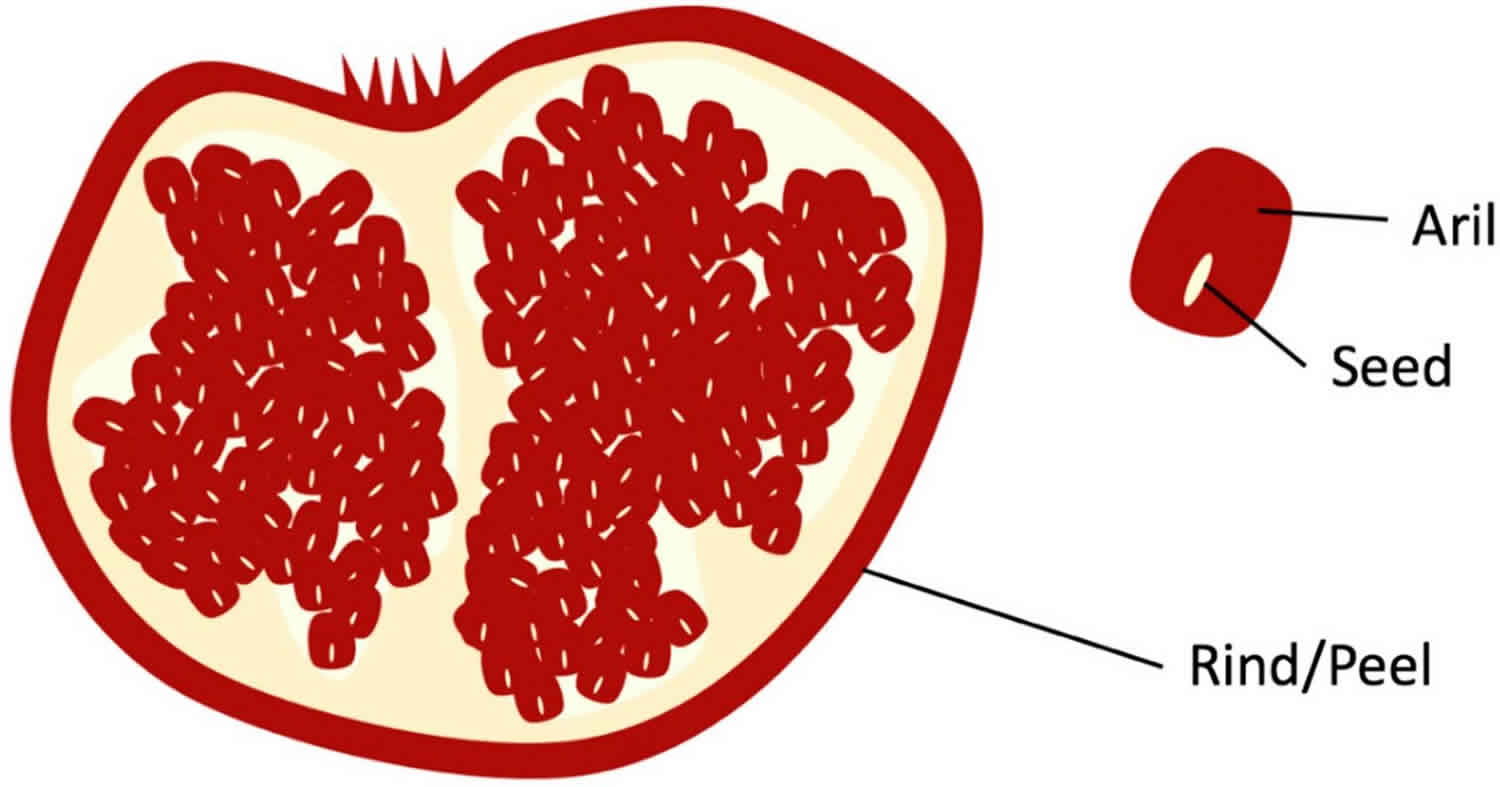

The pomegranate (Punica garanatum L.) fruit has a leathery rind (or husk) with many little pockets of edible seeds and juice inside. Researchers have studied all parts of the pomegranate for their potential health benefits. Those parts include the fruit, seed, seed oil, tannin-rich peel, root, leaf, and flower. The pomegranate has been used as a dietary supplement for many conditions including wounds, heart conditions, intestinal problems, and as a gargle for a sore throat.

Pomegranate is made into capsules, extracts, teas, powders, and juice products 1.

Pomegranate is a long-lived and drought-tolerant plant. Arid and semiarid zones are popular for growing pomegranate trees. They are widely cultivated in Iran, India, and the Mediterranean countries such as Turkey, Egypt, Tunisia, Spain, and Morocco 2. However, pomegranate is categorized as a berry but it belongs to its own botanical family, Punicaceae. The only genus is Punica, with one predominant species called P. granatum 3.

The pomegranate is an ancient fruit native to regions from the Himalayas in northern India to Iran. In recent years, however, cultivation of pomegranate has disseminated throughout many dry regions of the world, including parts of the United States. The trees can grow up to 30 feet in height. The leaves are opposite, narrow, oblong with 3-7 cm long and 2 cm broad. It has bright red, orange, or pink flowers, which are 3 cm in diameter with four to five petals. Edible pomegranate fruit has a rounded hexagonal shape, with 5-12 cm in diameter and weighing 200 g. The thick skin surrounds around 600 arils, which encapsulates the seeds 4.

Apart from fruit, pomegranate is available in various forms such as bottled juice (fresh or concentrated), powdered capsules, and tablets, which are derived from seed, fermented juice, peel, leaf and flower, gelatin capsules of seed oil extracts, dry or beverage tea from leaves or seeds, and other food productions such as jams, jellies, sauces, salad dressings, and vinegars. Anardana, which is the powdered form of pomegranate seed, is used as a form of spice 4.

Pomegranate nutrition facts

The 100 g edible portion of pomegranate contains water (77.93 g), protein (1.67 g), lipids (1.17 g), ash (0.53 g), carbohydrates (18.7 g), fiber (4 g) and sugars (13.67 g) (see Table 1).

Figure 1. Pomegranate rind and seed

Table 1. Pomegranate (Raw) Nutrition Content

| Nutrient | Unit | Value per 100 g | cup arils (seed/juice sacs) 87 g | pomegranate (4″ dia) 282 g | |

| Approximates | |||||

| Water | g | 77.93 | 67.8 | 219.76 | |

| Energy | kcal | 83 | 72 | 234 | |

| Protein | g | 1.67 | 1.45 | 4.71 | |

| Total lipid (fat) | g | 1.17 | 1.02 | 3.3 | |

| Carbohydrate, by difference | g | 18.7 | 16.27 | 52.73 | |

| Fiber, total dietary | g | 4 | 3.5 | 11.3 | |

| Sugars, total | g | 13.67 | 11.89 | 38.55 | |

| Minerals | |||||

| Calcium, Ca | mg | 10 | 9 | 28 | |

| Iron, Fe | mg | 0.3 | 0.26 | 0.85 | |

| Magnesium, Mg | mg | 12 | 10 | 34 | |

| Phosphorus, P | mg | 36 | 31 | 102 | |

| Potassium, K | mg | 236 | 205 | 666 | |

| Sodium, Na | mg | 3 | 3 | 8 | |

| Zinc, Zn | mg | 0.35 | 0.3 | 0.99 | |

| Vitamins | |||||

| Vitamin C, total ascorbic acid | mg | 10.2 | 8.9 | 28.8 | |

| Thiamin | mg | 0.067 | 0.058 | 0.189 | |

| Riboflavin | mg | 0.053 | 0.046 | 0.149 | |

| Niacin | mg | 0.293 | 0.255 | 0.826 | |

| Vitamin B-6 | mg | 0.075 | 0.065 | 0.211 | |

| Folate, DFE | µg | 38 | 33 | 107 | |

| Vitamin B-12 | µg | 0 | 0 | 0 | |

| Vitamin A, RAE | µg | 0 | 0 | 0 | |

| Vitamin A, IU | IU | 0 | 0 | 0 | |

| Vitamin E (alpha-tocopherol) | mg | 0.6 | 0.52 | 1.69 | |

| Vitamin D (D2 + D3) | µg | 0 | 0 | 0 | |

| Vitamin D | IU | 0 | 0 | 0 | |

| Vitamin K (phylloquinone) | µg | 16.4 | 14.3 | 46.2 | |

| Lipids | |||||

| Fatty acids, total saturated | g | 0.12 | 0.104 | 0.338 | |

| Fatty acids, total monounsaturated | g | 0.093 | 0.081 | 0.262 | |

| Fatty acids, total polyunsaturated | g | 0.079 | 0.069 | 0.223 | |

| Fatty acids, total trans | g | 0 | 0 | 0 | |

| Cholesterol | mg | 0 | 0 | 0 | |

| Other | |||||

| Caffeine | mg | 0 | 0 | 0 | |

Pomegranate Chemical Composition

46% weight per weight (w/w) of pomegranate is used as a juice, and the rest of it is considered to be waste. Pomegranate’s arils are depicted in Figure 1 as the edible red pulp that surrounds the seed that is used by juice manufacturing companies to produce pomegranate juice. The remaining solid waste from pomegranates, after juice extraction, the pomegranate rind and pomegranate seed contain various bioactive and nutritional components, such as flavonoids (e.g., anthocyanins), hydrolyzable tannins (e.g., punicalagin and ellagic acid), and fatty acids (e.g., punicic acid) 6. These components in pomegranate biowaste have various potential value addition applications in food and skin health 7. Table 2 shows some of the chemical properties of pomegranate rind and seed to help outline the various applications that add value to pomegranate’s biowaste as functional ingredients in food. For instance, pomegranate seed is a source of dietary fiber that has applications as a food additive in fiber-enriched products, including dough 8 and chicken nuggets 9.

The pomegranate rind is one of the waste components that comprises 43% w/w of the pomegranate fruit. Pomegranate seeds are another waste component of pomegranate and compose 11% w/w of the fruit. The oil content that is extracted from pomegranate seeds varies in weight percentages, depending on their cultivars, and it constitutes approximately 7.6–20% w/w of the pomegranate seed 10. The oil content of pomegranate varies depending on the climate of the growing region, the maturity of the fruit, cultivation practices, and storage conditions 11.

Table 2. Chemical properties of pomegranate seed and rind by dry weight

| Property | Seed Amount | Rind Amount |

| Moisture | 10.44–12.86% | 67.26–73.23% |

| Sugar | N/A | 30.65–34.83% |

| Crude Oil | 10.89–13.24% | N/A |

| Crude Protein | 6.71–8.11% | 3.96–7.13% |

| Crude Ash | 1.61–2.29% | 3.71–4.97% |

| Fiber | 17.33–27.84% | 28.10–33.93% |

| Pectin | N/A | 6.8–10.1% |

Pomegranate seed

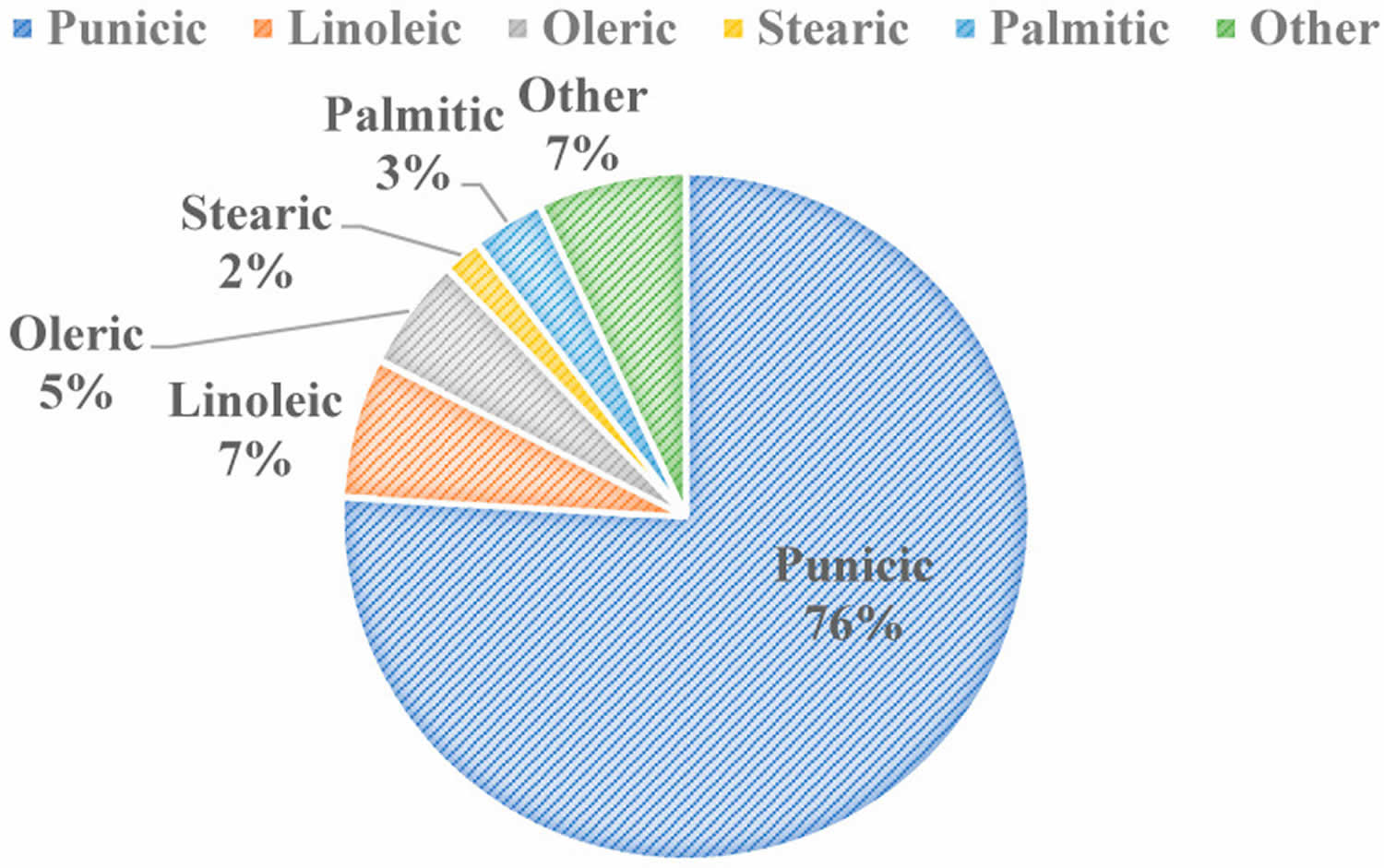

About 18% of dried and cleaned white pomegranate seeds are oil 12. Figure 2 shows the five major fatty acid components found in pomegranate seed oil. There are 45 identified different fatty acids in pomegranate seed oil, with conjugated fatty acids making up over 80% weight/volume percentage (w/v%) of its composition 13. There are some phytoestrogen compounds in pomegranate seeds that have sex steroid hormones similar to those in humankind. The 17-alpha-estradiol is a mirror-image version of estrogen 4.

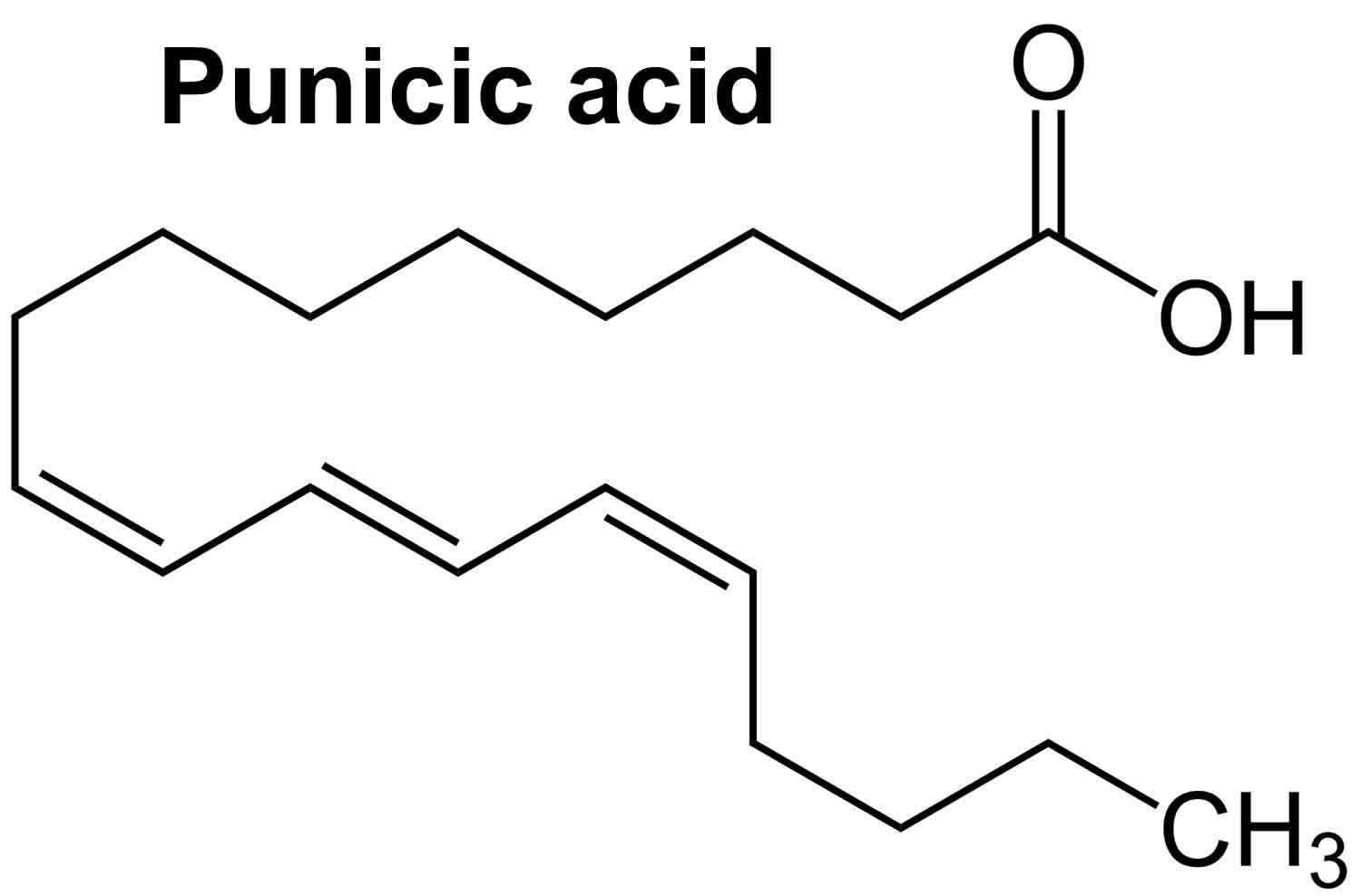

Punicic acid is the main fatty acid (~76%) in pomegranate seed oil, being followed closely by linoleic and oleic acids 14. Some studies show the health benefits of specific fatty acid components within the pomegranate seed oil, such as punicic acid’s role in preventing diabetes and related obesities 15. It has also been shown that punicic acid can inhibit skin cancer 16 and prevent type 2 diabetes in rats 17 and it possesses anti-diabetic, anti-obesity, anti-inflammatory, anticancer, and antioxidant properties 18. Similarly, a wide scope of applications for pomegranate seed oil extracts as a whole exist, including in food packaging, fat substitution, animal food production and functional ingredient, and antimicrobial agent and pharmaceutical capacities 13. There is an increasing demand and acceptance for pomegranate seed oil for consumers in the cosmetics, food, and pharmaceutical industries globally due to pomegranate seed oil’s valuable phytochemical composition and functional properties. The oil also has feasible extraction procedures, and it has applications in cosmetic products, especially in Europe 13.

Figure 2. Pomegranate seed oil major fatty acids

Figure 3. Punicic acid chemical structure

Pomegranate juice

Pomegranate juice is a good source of fructose, sucrose, and glucose 12. Pomegranate juice also has some of the simple organic acids such as ascorbic acid, citric acid, fumaric acid, and malic acid. In addition, it contains small amounts of all amino acids, specifically proline, methionine, and valine. Both pomegranate juice and peel are rich in polyphenols. The largest classes include tannins and flavonoids that indicate pharmacological potential of pomegranate due to their strange antioxidative and preservative activities 4.

Ellagitannin is a type of tannins; it can be broken down into hydroxybenzoic acid such as ellagic acid. It is widely used in plastic surgeries, which prevents skin flap’s death due to its antioxidant activity 12. Two other ellagitannins that are found in both pomegranate juice and peel are punicalagin and punicalin 12. Several classes of pomegranate flavonoids include anthocyanins, flavan 3-ols, and flavonols. Pomegranate juice and peel have catechins with a high antioxidant activity. They are essential compounds of anthocyanin’s production with antioxidant and inflammatory role. Anthocyanins cause the red color of juice, which is not found in the peel. All pomegranate flavonoids show antioxidant activity with indirect inhibition of inflammatory markers such as tumor necrosis factor-alpha (TNF-α) 4.

Pomegranate rind

Pomegranate rind is the main non-edible portion that constitutes approximately 43% w/w of the fruit. Pomegranate rind is a source of bioactive compounds, including flavonoids, complex polysaccharides, minerals, and hydrolyzable tannins, such as punicalagin, ellagic, and gallic acid 7. Pomegranate rind has a variety of applications in wastewater treatment, including being used in the removal of phenolic compounds 19, in the removal of dye from wastewater by conversion of pomegranate rind to activated carbon 20 and as renewable energy material sources 21. Pomegranate rind is a rich source of dietary fiber and pectin, as shown in Table 2. In one study, pomegranate rind powder was added to the diet of hypercholesteremic rats as a source of dietary fiber, and it has been shown to combat the risks that are associated with hypercholesterolemia such as lipid peroxidation 22. Pomegranate rind has also been supplemented in foods, such as cookies, to enhance its nutritional benefits 23. Pomegranate rind’s phenolics assisted in improving oxidative stability during food storage in addition to significantly increasing the cookies’ dietary fiber content, which allows the product to be marketed towards health-conscious consumers 6. The phenolics in cookies also improve the antioxidant activity in the gastrointestinal tract at a 7.5% w/w of rind extract and regulates glucose metabolism by inhibiting alpha-glucosidase 24. Alpha glucosidase enzymes catalyze hydrolysis of starch to produce glucose. In humans, these enzymes aid digestion of dietary carbohydrates and starches to produce glucose for intestinal absorption, which in turn, leads to increase in blood glucose levels. Inhibiting the function of these enzymes in patients with type-2 diabetes may reduce hyperglycemia. These findings suggest additional health benefits in the digestive tract, using pomegranate rind in bakery foods. In addition, pomegranate pectin has found food-related applications as a gelling agent 25 and an emulsifier 26. The properties and bioactive composition of pomegranate rind are what allows it to have several applications in skin health and food industries. Table 2 shows the chemical properties of the pomegranate seed and rind, which correspond to some of the potential uses of pomegranate biowaste in food additives.

Pomegranate bark and roots

The pomegranate tree’s bark and roots are rich sources of chemicals called alkaloids. They are carbon-based substances; they were used to treat worms in the human gastrointestinal tract in traditional medicine 4.

How to Eat a Pomegranate

Inside a pomegranate are those glistening red jewels – they are called arils (juice sacs). The arils are full of delicious, nutritious sweet juice that surround a small white crunchy seed. You can eat the whole arils including the fiber-rich seeds, or spit out the seeds if you prefer- it’s your choice. The rind and the white membranes surrounding the arils are bitter and we don’t suggest eating them- although some say even that part of the pomegranate has medicinal value.

How do you remove the seeds/arils?

To remove the seeds follow this simple 3 steps process:

Step 1. Cut the crown end off a pomegranate. Then cut the pomegranate in half vertically.

Step 2. Hold the pomegranate half, cut side down, over a deep bowl the roll out the arils with your fingers and discard everything else.

Step 3. Strain out the water. Then eat the succulent arils whole, seeds and all.

How do you juice a pomegranate ?

There are 3 main methods to get fresh squeezed juice:

- Juicer Method: Cut the fresh pomegranate in half as you would a grapefruit. The Pomegranate Council 27 recommends using a hand-press juicer to juice a pomegranate. If you use an electric juicer, take care not to juice the membrane, so that the juice remains sweet. Strain the juice through a cheesecloth-lined strainer or sieve. Be cautious, as pomegranate juice can stain.

- Blender Method: Place 1 ½ to 2 cups seeds in a blender; blend until liquefied. Pour through a cheesecloth-lined strainer or sieve.

- Rolling Method: On a hard surface, press the palm of your hand against a pomegranate and gently roll to break all of the seeds inside (crackling stops when all seeds have broken open). Pierce the rind and squeeze out juice, or poke in a straw and press to release the juice. NOTE: Rolling can be done inside a plastic bag to contain any juice that may leak through the skin 27.

Health effects of Pomegranate

Pomegranate has been heavily used in various ancient medicines, such as Ayurveda, for treatment of diabetes. As a result of its rapidly increasing production and consumption throughout the world, a considerable amount of recent research has explored the potential of pomegranate to fight for obesity and diabetes.

A study in male mice showed that consumption of pomegranate seed oil reduced weight gain, improved key markers that lead to the development of type-2 diabetes, and improved insulin sensitivity – all suggesting a diminished develpoment to type-2 diabetes 28. Experiments in 3T3-L1 pre-adipocytes demonstrated that punicic acid, a conjugated linolenic acid found in pomegranate, activates peroxisome proliferator-activated receptor-gamma (PPAR-γ), an important target of insulin action and energy metabolism. Pucinic acid also augmented PPARγ downstream gene expression, and demonstrates an impaired ability to alleviate the pathogenesis of diabetes in PPARγ knockdown immune cells 29. This suggests that pomegranate may be a natural complement to the synthetic thiazolidinediones (anti-diabetic drugs and PPAR-γ agonists), and alleviate pathogenesis of obesity and diabetes through a PPAR-γ mediated mechanism. In the Otsuka Long-Evans Tokushima Fatty rat model, pomegranate seed oil rich in punicic acid significantly decreased hepatic triacylglycerol contents and levels of monounsaturated fatty acid (MUFA) , which can be preventive for development of hepatic steatosis 30. In obese rats, a model of metabolic syndrome, supplementation with pomegranate fruit extract and juice markedly decreased expression of vascular inflammatory markers such as thrombospondin and TGF-β 31. Also, a 4 week clinical trial administering 400 mg of pomegranate seed oil twice a day in hyperlipidemic subjects significantly improved the lipid profile as shown by a decreased triglyceride:HDL “good” cholesterol ratio 32.

Furthermore, pomegranate has shown dramatic antioxidant potential. It has been shown that pomegranate fruit extract, which is rich in polyphenolic antioxidants, represses the expression of oxidation-sensitive genes at the site of stress. More recently, studies show that pomegranate juice extract may prevent high blood pressure induced by Angiotensin II in diabetic rats by ameliorating oxidative stress and inhibiting Angiotensin-converting enzyme (ACE) activity 33. Research is also heading towards development of a synergistic combination of various extracts. Recently, Fenercioglu et al 34 demonstrated antagonizing effects on oxidative stress and lipid peroxidation of a supplement containing pomegranate extract, green tea extract, and absorbic acid in type 2 diabetic patients. All the above mentioned results clearly suggest that pomegranate can play an important role in the prevention of diabetes, obesity and their associated complication. Basis on these findings it can be suggested that pomegranate can considered as a rational complementary therapeutic agent to ameliorate obesity, diabetes and the resultant metabolic syndrome.

Pomegranate can induce its beneficial effects through its various metabolites. The antioxidant and antiatherosclerotic potentials of pomegranate are mainly relevant to the high polyphenol concentrations in pomegranate fruit such as ellagitannins and hydrolysable tannins 35. COX-1 and COX-2 enzymes and IL-1 β activity can be inhibited by pomegranate fruit extract 36.

It is suggested that pomegranate can antagonize the stimulation of mRNA of MMP-9 in THP-1/monocytes. The whole fruit and compounds inhibit TNF-induced MMP-9 promoter activity 37. Urolithins are metabolites that are metabolized by the human intestinal microflora. These compounds decreased MMP-9 sretion and mRNA levels induced by HZ or TNF. It is suggested that ellagitannins are responsible for the control of excessive production of MMP-9, which could result in decreased production of noxious cytokine TNF 38. TNF cytokines promote NFκB binding to target sequences while inducing transcription of several genes such as the MMP-9 gene 39. Ellagitannins prevent NFκB promoter activity by blocking NFκB-driven transcription and affecting the entire cytokine cascade. Ellagitannins inhibit the activation of inflammatory pathways such as MAPK 40. In addition, pomegranate compounds could inhibit angiogenesis through the downregulation of vascular endothelial growth factor in cancers 41.

Dietary fiber

Dietary fiber is found in fruits, vegetables, and whole grains. A high fiber diet helps to alleviate constipation, maintain healthy bowel movements, lower cholesterol levels, and control blood sugar levels 42. Pomegranate seed is shown to have a dietary fiber content of 17.33–27.84% w/w when six varieties of pomegranates from Turkey were tested (Table 2) 43.

Pomegranate seed powder is a form of dietary fiber that can be used as a food additive. Pomegranate seed powder was used to replace a percentage of lean meat in the formulation of chicken nuggets in a study 9. The results showed that chicken nuggets had increased sensory attributes with a 3% w/w incorporation of pomegranate seed powder. There was also a significant increase in the crude fiber content of the nuggets with increasing levels of pomegranate seed powder. However, there was decreased emulsion stability as a result of decreased pH and water holding capacity and increased fat due to the abundance of fatty acids in pomegranate seeds 9. In a similar study on bread making, pomegranate seed flour was used to replace up to 5% w/w of the wheat flour without drastically changing the sensory qualities of the bread. The resulting bread was labeled as a good source of fiber with lower production costs 8. This is especially important because the bran and germ of wheat are taken out when wheat is milled, which causes a marked decrease in the dietary fiber content of the flour. When a portion of wheat flour was replaced with punicic acid-rich pomegranate seed powder, the bread’s dietary fiber, punicic acid, total polyphenol content, and radical scavenging activity were all increased 8. However, incorporating a 10% w/w level of pomegranate seed powder led to a slight decrease in the dough’s volume, crumb hardness, rheological properties, and sensory scores 44. Pomegranate rind is also a source of dietary fiber and, when supplemented in cookies at an acceptable level of below 7.5% w/w, increases the crude fiber content by 80%. There was overall acceptability of the cookies, although this addition may have been attributed to the hardening of the cookies and a decline in sensory scores 23.

Because fiber is an important nutrient needed to maintain healthy stool and bowel movements, the above studies show the merits of pomegranate in adding fiber to food products, such as chicken nuggets and dough, without drastically changing their sensory scores or quality. They also show the potential of pomegranate to be used as a source of fiber in other food products, such as granola bars. Pomegrain bars have been formulated in one study in optimized conditions with 55% w/w pomegranate seed powder.

Prostate cancer

After lung cancer, the second leading cause of male cancer death is prostate cancer worldwide. Its progress before onset of symptoms is slow; therefore, pharmacological and nutritional interventions could affect the quality of patient’s life by delaying its development 45.

It was shown that pomegranate fruit could be used in the treatment of human prostate cancer because it could inhibit cell growth and induce apoptosis. It leads to induction of pro-apoptotic proteins (Bax and Bak) and downregulation of anti-apoptotic proteins (Bcl-xL and Bcl-2) 46. Moreover, the presence of NFκB and cell viability of prostate cancer cell lines has been inhibited when using pomegranate fruit extract, because it blocks NFκB 47. Polyphenols of fermented juice and pomegranate oil can inhibit the proliferation of LNCaP (epithelial cell line derived from a human prostate carcinoma), PC-3, and DU145 human prostate cancer cell lines. These effects were the result of changes in cell cycle distribution and apoptosis induction 46. In addition, it is reported that pomegranate fruit extract oral administration in nude mice implanted with androgen-sensitive CWR22RV1 cells caused significant decrease in serum prostate-specific antigen (PSA) level and inhibited tumor growth 47. Besides, the observed increase in NFκB activity during androgen dependence to androgen independence transition in the LAPC4 xenograft model was terminated 48.

One small study 49 from 2006 found that drinking a daily 227ml (8oz) glass of pomegranate juice significantly slowed the progress of prostate cancer in men with recurring prostate cancer. This was a well-conducted study, but more are needed to support these findings.

A more recent study 50 from 2013 looked at whether giving men pomegranate extract tablets prior to surgery to remove cancerous tissue from the prostate would reduce the amount of tissue that needed to be removed. The results were not statistically significant, meaning they could have been down to chance.

Breast cancer

Fermented pomegranate juice has double the antiproliferative effect compared to fresh pomegranate juice in human breast cancer cell lines MCF-7 (breast cancer cell line isolated in 1970 from a 69-year-old Caucasian woman) and MB-MDA-231. In addition, pomegranate seed oil caused 90% prevention of proliferation of MCF-7 cells 51, 52.

Lung cancer

Pomegranate fruit extract can inhibit several signaling pathways, which can be used in the treatment of human lung cancer. Pathways include Mitogen-activated protein kinases (MAPK) PI3K/Akt and NFκB. In addition, there was a 4 day delay in the appearance of tumors (from 15 to 19 days) in mice implanted with A549 cells.[10] These studies indicate the chemopreventive effects of pomegranate fruit extract 4.

Colon cancer

Adams et al. 53 have reported the anti-inflammatory effects of pomegranate juice on the signaling proteins in HT-29 human colon cancer cell line. Reduction in phosphorylation of the p65 subunit of NFκB, its binding to the NFκB response, and 79% inhibition in TNF-α protein expression have been observed with 50 mg/L concentration of pomegranate extract.

Skin cancer

It has been demonstrated that pomegranate oil has chemopreventive efficacy in mice. Reduced tumor incidence (7%), decrease in tumor numbers, reduction in ornithine decarboxylase activity (17%), significant inhibition in elevated Tissue plasminogen activator-mediated skin edema and hyperplasia, protein expression of ODC and COX-2, and epidermal ODC activity have been reported with pomegranate oil treatments 54, 55. Pomegranate extract in various concentrations (5-60 mg/L) was effective against UVA- and UVB-induced damage in SKU-1064 fibroblast cells of human, which was relevant in reducing NFκB transcription, downregulating proapoptotic caspase-3, and elevating the G0/G1 phase associated with deoxyribonucleic acid (DNA) repair 56.

Cardiovascular diseases

Pomegranate juice is an affluent source of polyphenols with high antioxidative potential. Moreover, its antiatherogenic, antihypertensive, and anti-inflammatory effects have been shown in limited studies in human and murine models 35.

Hypertension is the most common disease in primary care of patients. It is found in comorbidity with diabetes and cardiovascular disease, and the majority of patients do not tend to be medicated. Pomegranate juice prevents the activity of serum angiotensin-converting enzyme and reduces systolic blood pressure 57. Angiotensin II acute subcutaneous administration causes increased blood pressure in diabetic Wistar rats. It has been shown that pomegranate juice administration (100 mg/kg) for 4 weeks could reduce the mean arterial blood pressure 58. Pomegranate juice consumption resulted in 30% decrease in carotid intima-media thickness after 1 year. The patient’s serum paraoxonase 1 activity showed 83% increase, whereas both serum low dwnsity lipoprotein (LDL) basal oxidative state and LDL susceptibility to copper ion significantly decreased by 90% and 95%, respectively 59.

Punicic acid, which is the main constituent of pomegranate seed oil, has antiatherogenic effects. In a study on 51 hyperlipidemic patients, pomegranate seed oil was administered twice a day (800 mg/day) for 4 weeks. There was a significant decrease in triglycerides (TG) and TG: High density lipoprotein (HDL) cholesterol ratio by 2.75 mmol/L and 5.7 mmol/L, respectively, whereas serum cholesterol, LDL-C, and glucose concentration remained unchanged 60.

High plasma LDL concentration is the major risk factor for atherosclerosis. Therefore, LDL modifications, including oxidation, retention, and aggregation, play a key role in atherosclerosis as well. Studies have shown that consuming pomegranate juice for 2 weeks resulted in declined retention and aggregation of LDL susceptibility and increased activity of serum paraoxonase (a protective lipid peroxidation esterase related to HDL) by 20% in humans. Pomegranate juice administration in mice for 14 weeks showed reduced LDL oxidation by peritoneal macrophages by more than 90%, which was because of reduced cellular lipid peroxidation and superoxide release. The uptake of oxidized LDL showed 20% reduction in mice. The size of atherosclerotic lesions reduced by 44% after pomegranate juice supplementation 61. Moreover, pomegranate juice administration to apolipoprotein E-deficient mice with advanced atherosclerosis for 2 months reduced oxidized LDL (31%) and increased macrophage cholesterol efflux (39%) 62.

In cultured human endothelial cells and hypercholesterolemic mice, both pomegranate juice and fruit extract reduced the activation of ELK-1 and p-CREB (oxidation-sensitive responsive genes) and elevated the expression of endothelial nitric oxide synthase. It is suggested that polyphenolic antioxidant compounds in pomegranate juice are responsible for the reduction of oxidative stress and atherogenesis 63.

In another study 64, concentrated pomegranate juice was shown to reduce heart disease risk factors. Administration of concentrated pomegranate juice to 22 diabetic type 2 patients with hyperlipidemia could significantly reduce TC, LDL-C, LDL-C: HDL-C ratio, and TC: HDL-C ratio. However, it was unable to decrease serum TG and HDL-C concentrations.

Oral administration of pomegranate flower aqueous extract in streptozotocin-induced albino Wistar rats in both 250 mg/kg and 500 mg/kg doses for 21 days could significantly reduce fibrinogen (FBG), TC, TG, LDL-C, and tissue lipid peroxidation level and increased the level of HDL-C and glutathione content 65.

Heart fibrosis increases among diabetics, which results in impairing cardiac function. Endothelin (ET)-1 and NFκB are interactive fibroblast growth regulators. It is suggested that pomegranate flower extract (500 mg/kg/day) in Zucker diabetic fatty rats could reduce the ratios of van Gieson-stained interstitial collagen deposit area to a total left ventricular area and perivascular collagen deposit areas to coronary artery media area in the heart and diminishes cardiac fibrosis in these rats. In addition, overexpressed cardiac fibronectin and collagen I and II messenger RNAs (mRNAs) were inhibited. It also decreased the upregulated cardiac mRNA expression of ET-1, ETA, inhibitor-κBβ, and c-jun. Pomegranate flower extract is a dual activator of peroxisome proliferator-activated receptor (PPAR)-α and γ and improves hyperlipidemia, hyperglycemia, and fatty heart in diabetic fatty Zucker rats 66, 67.

Punicic acid caused a dose-dependent increase in PPAR alpha and gamma reporter activity in 3T3-L1 cells. Dietary punicic acid reduced plasma glucose, suppressed NFκB activation and unregulated TNF-α expression and PPAR-α/γ responsive genes in adipose tissue and skeletal muscle 68.

Pomegranate leaf extract was administered (400 and 800 mg/kg/day) to high-fat-diet-induced obese and hyperlipidemic mouse models for 5 weeks. The results indicated significant reduction in body weight, energy intake (based on food intake), serum total cholesterol (TC), TG, FBG, and TC/HDL-C ratio. Intestinal fat absorption was inhibited as well 69.

The high fat diet (HFD) with 1% pomegranate seed oil (rich source of punicic acid) was administered for 12 weeks to induce obesity and insulin resistance in mice. The pomegranate seed oil-fed group exhibited lower body weight (4%) and body fat mass (3.1%) compared with only HFD-fed mice. A clear improvement was observed in peripheral insulin sensitivity (70%) in pomegranate seed oil-administered rats 70.

Fatty liver is the most common abnormal liver function among diabetics. Pomegranate flower was examined for its antidiabetic effects on diabetic type II and obese Zucker rats. Rats fed with 500 mg/kg/day of pomegranate flower extract for 6 weeks showed decreased ratio of liver weight to tibia length, lipid droplets, and hepatic TG contents. In addition, it increased PPRA-α and Acyl-COA oxidase mRNA levels in HepG2 cells 71.

In a study by de Nigris et al. 72, they compared the influence of pomegranate fruit extract with pomegranate juice on nitric oxide and arterial function in obese Zucker rats. They have demonstrated that both pomegranate fruit extract and juice significantly reduced the vascular inflammatory markers expression, thrombospondin, and cytokine TGFP 1. Increased plasma nitrite and nitrate were observed with administration of either pomegranate fruit or juice.

Many studies have reported the anti-inflammatory potential of pomegranate extract. In a study on 30 Sprague-Dawley rats with acute inflammation due to myringotomy, it was observed that 100 μl/day of pomegranate extract could significantly reduce reactive-oxygen species (ROS) levels. The extract was administered 1 day before and 2 days after surgery. Reduced thickness of lamina propria and vessel density was reported as well 73. Both ellagitannins and ellagic acid are the main components of pomegranate extract, which have anti-inflammatory properties. They are metabolized by gut microbiota to yield urolithins. It is suggested that urolithins are the main components responsible for the anti-inflammation properties of pomegranate. It is suggested that NFκB activation, MAPK downregulation of COX-2, and mPGES-1 expression were inhibited through a decrease in PGE2 production 74. Neutrophils play key roles in inflammatory processes by releasing great amounts of ROS generated by NADPH-oxidase and myeloperoxidase. It is indicated that punicic acid exhibited a potent anti-inflammatory effect via prevention of TNF-α-induced priming of NADPH oxidase by targeting the p38MAPKinase/Ser 345-p 47 phox-axis and releasing MPO 75. Hyperglycemia results in oxidative stress in diabetes mellitus, which is a major factor in the pathogenesis of cardiovascular disease. Results suggested that pomegranate extract, owing to its polyphenol-rich antioxidants (oleanolic, ursolic, and gallic acids), could prevent cardiovascular complications through decrease in LDL, increase in HDL, serum paraoxonase 1 stability and activity, and nitric oxide production 76, 77, 78.

Anti-inflammatory effect

Pomegranate rind extract was tested on ex-vivo porcine skin for its anti-inflammatory effects. The punicalagin permeated the skin, thus downregulating COX-2, an inflammatory enzyme 79. A hydrogel containing pomegranate rind extract and zinc sulfate was formulated by the same research team as a topical treatment for Herpes simplex virus (HSV) infection. The hydrogel exhibited virucidal and anti-inflammatory effects, with punicalagin permeating regions of the skin that are susceptible to infection 80. This has relevance in the growing need for novel clinical products to combat HSV. Another study using the rind extract’s punicalagin with zinc (II) ions established virucidal and therapeutic effects against HSV infections, such as the common cold sore, in order to further emphasize this potential application 81.

In addition to bioactive components of pomegranate rind, pomegranate seed oil, when topically applied, alleviates oxidative and inflammatory stress brought on the skin by UV irradiation. A topical hydrogel that was formulated with silibinin-loaded pomegranate oil-based nanocapsules had an anti-inflammatory effect on mice skin damaged by UVB induced radiation 82. Furthermore, pomegranate seed oil nanoemulsions can provide photoprotection against UVB-induced damage of DNA in human keratinocyte HaCaT cells, which constitute most of the epidermis 83. In another study on keratinocyte cells, pomegranate extract phenolics, including punicalagin, EA, and urolithin A, had protective effects against hydrogen peroxide-induced oxidative stress and cytotoxicity 84. These studies demonstrate the existing potential of pomegranate extracts for use in sunscreen and cosmetics products. Furthermore, the topical application of pomegranate seed oil decreased skin tumor development and multiplicity, and it has shown applications as a chemo-preventive agent for skin cancer 16.

Osteoarthritis

The most common forms of arthritis are osteoarthritis and its major progressive degenerative joint disease, which could affect joint functions and quality of life in patients. It is mediated by proinflammatory cytokines such as IL-1 and TNF-α. MAPKs are important due to their inflammatory and cartilage damage regulation 85. P38-MAPKs are responsible for regulating cytokine production, neutrophils activation, apoptosis, and nitric oxide synthesis. The MAPK family phosphorylates a number of transcription factors such as runt-related transcription factor-2 (RUNX-2) 86.

Pomegranate extract, with its rich source of polyphenols, can inhibit IL-1 β-induced activation of MKK3, DNA-binding activity of RUNX-2 transcription factor, and p38 α-MAPK isoform 85.

Rheumatoid arthritis

Rheumatoid arthritis is an autoimmune disease that affects 0.5-1% of people worldwide. Women are afflicted more than men. This inflammatory disease is characterized by inflammation and bone erosion 85, 86. Critical mediators in the pathogenesis of rheumatoid arthritis are TNF-α, IL-1 β, MCP1, Inducible nitric oxide synthase (iNOS), and COX-2-agents, which are stimulated by p38-MAPK and NFκB activation 87, 88.

The pomegranate has been used for centuries to treat inflammatory diseases, and people with rheumatoid arthritis sometimes take dietary supplements containing a pomegranate extract called POMx. However, little is known about the efficacy of POMx in suppressing joint problems associated with rheumatoid arthritis.

In a recent study, researchers from Case Western Reserve University and Aligarh (India) Muslim University used an animal model of rheumatoid arthritis—collagen-induced arthritis (CIA) in mice—to evaluate the effects of POMx. The animals received either POMx or water by stomach tube before and after collagen injection to induce arthritis. POMx significantly reduced the incidence and severity of CIA in the mice. The arthritic joints of the POMx-fed mice had less inflammation, and destruction of bone and cartilage were alleviated. Consumption of POMx, the researchers also concluded, selectively inhibited signal transduction pathways and cytokines critical to development and maintenance of inflammation in rheumatoid arthritis 89. Severity of arthritis, joint inflammation, and IL-6 level were significantly reduced in pomegranate extract-fed mice 90.

Although previous studies of POMx found cartilage-protective effects in human cell cultures, this is the first study to observe positive effects in a live model. The researchers note that the data from this study suggest the potential efficacy of POMx for arthritis prevention, but not for treatment in the presence of active inflammation; future studies will address disease-modifying effects of POMx. They also note that clinical trials are needed before POMx can be recommended as safe and effective for rheumatoid arthritis-related use in people 89.

Antibacterial and antifungal effect

Since bacterial resistance to antimicrobial drugs is increasing, medicinal plants have been considered as alternative agents. Pomegranate has been widely approved for its antimicrobial properties 91, 92, 93. It has been shown that dried powder of pomegranate peel has a high inhibition of Candida albicans 94. In addition, antimicrobial effects of both methanol and dichloromethane pomegranate extracts have been demonstrated on the Candida genus yeast as pathogen-causing disease in immunosuppressive host 95. Methicillin-resistant staphylococcus aureus (MRSA) and methicillin-sensitive staphylococcus aureus (MSSA) (multiple antibiotics resistant) produce panta valentine leukocidin (PVL) toxin, which can lead to higher levels of morbidity and mortality 96, 97. It is indicated that a combination of pomegranate peel extract with Cu (II) ions exhibit enhanced antimicrobial effects against isolated MSSA, MRSA, and PVL 98. One of the leading etiological bacteria of urinary tract infections is Escherichia Coli. Strong antibacterial activity of ethanol extract against E. coli has been shown 99.

Skin

Pomegranate rind and bioactive seed compounds can be integrated into skin health products, demonstrating the potential that biowaste can be converted into value-added products 6. Ellagic acid and punicalagin are both bioactive compounds of pomegranate rind that promote skin health by inhibiting tyrosinase and initiating anti-inflammatory and anti-fungal effects 79. Pomegranate seed oil is rich in punicic acid, which gives it protective and anti-inflammatory characteristics to act against ultraviolet (UV)-induced radiation 100. Solar ultraviolet (UV) radiations are the primary causes of many biological effects such as photoaging and skin cancer. These radiations resulted in DNA damage, protein oxidation, and matrix metalloproteinases induction. In one study, the effects of pomegranate juice, extract, and oil were examined against UVB-mediated damage. These products caused a decrease in UVB-induced protein expression of c-Fos and phosphorylation of c-Jun 101. On the other hand, production of proinflammatory cytokines IL-1 β and IL-6 was decreased by topical application of 10 micromol/L of ellagic acid. The inflammatory macrophages infiltration was blocked in the integuments of SKH-1 hairless UVB-exposed mice for 8 weeks 102. Furthermore, pomegranate seed oil can act as an inhibitor for aging-induced glycation, a process that negatively affects skin elasticity 103.

Skin whitening

Pomegranate has one of the highest levels of ellagic acid among fruits and vegetables 6. Ellagic acid is a phenolic component that is used to protect skin against oxidative stress 104. Ellagic acid is currently approved as a lightening ingredient for cosmetic formulations due to its ability to chelate copper ions that are present in tyrosinase enzymes, which are the main enzymes catalyzing the production of melanin 105.

Ellagic acid that is found in pomegranate has advantageous treatment abilities for UVB-induced hyperpigmentation 100. In one study, pomegranate rind extract containing 90% w/w ellagic acid was orally administered to UV irradiated guinea pigs to test its skin whitening effect. The extract taken orally had a comparable whitening effect to L-ascorbic acid (vitamin C), which is a known tyrosinase inhibitor on UV-induced pigmentation, and reduced the number of DOPA-positive melanocytes, whereas L-ascorbic acid did not 106. Apart from its skin whitening effect, ellagic acid in pomegranate has more skin health applications that will be discussed in the next sections.

Skin wrinkling and skin aging

Pomegranate extract also has an anti-aging effect against skin wrinkling and it can increase skin elasticity. Pomegranate seed oil can improve the striae distensae skin condition, which is associated with a lack of skin elasticity. It was tested in an oil-in-water cream with Croton lechleri resin, which increased the thickness, hydration, and elasticity values of the dermis 107. Another topical oil-in-water emulsion was formulated with pomegranate extract, donkey milk, and UV filters. In addition to an overall decrease in brown pigmentation, the emulsion had anti-aging effects on the skin, such as a decreased wrinkle count by 32.9%, decreased wrinkle length by 9.6%, and increased skin firmness and elasticity by 9.6%. This suggests that these effects are due to the synergistic potency of the ingredients of the formulation 108. Pomegranate ellagic acid, in particular, has the ability to prevent UVB-induced thickening of the dermis, a process that can lead to skin wrinkling 109.

Glycation, which is also known as the Maillard reaction, is a process that creates advanced glycation end products (AGEs), which is partly induced by aging 103. It is also a non-enzymatic, irreversible reaction between reducing sugars and proteins 110. Skin glycation affects collagen in a way that results in the deterioration of skin elasticity. The anti-glycation property of a polysaccharide fraction from pomegranate extract was studied by evaluating the content of fructosamine, an early glycation product. The pomegranate extract acted as a glycation inhibitor due to both its free radical scavenging ability and its inhibition of fructosamine formation by modification of the amino or carbonyl groups in the Maillard reaction 103. More recently, oral dosages of 100 mg/day pomegranate extract were given to post-menopausal healthy females. The results showed a decrease in glycative stress markers in those who had received the extract dosages 111. Pomegranate extract was also found to be effective in firming skin after weight change or cosmetic surgery, as it increased the synthesis of glycosaminoglycans in the skin 112. In another application, pomegranate extract from sterols with shale extract was used in a lip gloss formulation to treat rough, dry, or cracked lips and reduce the appearance of wrinkles 113. In short, pomegranate extract can be considered to be beneficial for eliminating wrinkles that are induced by skin aging and damage from UV.

Burn and wound healing

In addition to its skin whitening and anti-aging effects, ellagic acid from pomegranate rind extract has a protective effect on sunburns at low doses (100 mg/day ellagic acid) 114. Pomegranate extract with 40% w/w ellagic acid also has a healing effect on deep second-degree burn wounds in rats through the induction of collagen formation, which strengthens wounded tissue and speeds up the healing process 115. The same extract can also enhance the healing process for incision wounds on rats by increasing collagen content and angiogenesis while decreasing polymorphonuclear leukocytes infiltration, which causes tissue damage during inflammation 116. Furthermore, ellagic acid and pomegranate rind extract positively contribute to increasing tensile strength in rat incision wounds. Although a high dose of ellagic acid alone can inhibit polymorphonuclear leukocytes infiltration, it cannot produce significant amounts of collagen. This is an indication of the synergistic effect of pomegranate extract with ellagic acid on healing wounds 117.

Dental effects

The interbacterial coaggregations and these bacterial interactions with yeasts are related to the maintenance of oral microbiota. It is indicated that dried, powdered pomegranate peel shows a strong inhibition of C. albicans with a mean zone of 22 mm. In another study, the antiplaque effect of pomegranate mouth rinse has been reported 118. In addition, hydroalcoholic extract of pomegranate was very effective against dental plaque microorganisms (84% decrease (cfu/ml)) 119.

Reproductive system

One of the main constituents (16%) of the methanolic pomegranate seed extract is beta-sitosterol. It is suggested that the extract is a potent phasic activity stimulator in rat uterus, which happens due to the non-estrogenic effects of beta-sitosterol on inhibiting sarco-endoplasmic reticulum Ca2+ -ATPase (SERCA) and K channel, which resulted in contraction by calcium entry on L-type calcium channels and myosin light chain kinase (MLCK). It is demonstrated that pomegranate fruit extract has an embryonic protective nature against adrianycin-induced oxidative stress (adrianycin is a chemotherapeutic drug used in cancer treatment) 120. Moreover, pomegranate juice consumption could increase epididymal sperm concentration, motility, spermatogenic cell density, diameter of seminiferous tubules and germinal cell layer thickness 121.

Alzheimer’s Disease

Hartman et al. 122 showed that mice treated by pomegranate juice have 50% less soluble Abeta 42 accumulation and amyloid deposition in the hippocampus, which could be considered for Alzheimer’s disease improvement.

Malaria

In the presence of pomegranate fruit rind, the induced MMP-9 mRNA levels by haemozoin or TNF was decreased, which may be attributed to the antiparasitic activity and the inhibition of the proinflammatory mechanisms responsible in the onset of cerebral malaria 123, 124.

HIV

The anti-HIV-1 microbicide of pomegranate juice blocks virus binding to CD4 and CXCR4/CCR5, thereby preventing infection by primary virus clades A to G and group O 125.

Pomegranate safety

Many studies have been carried out on the different components derived from pomegranate but no adverse effects have been reported in the examined dosage. Histopathological studies on both sexes of OF-1 mice confirmed the non-toxic effects of the polyphenol antioxidant punicalagin. Besides, in a study on 86 overweight human subjects who received 1420 mg/day of pomegranate fruit extract in tablet form for 28 days, no side effects or adverse changes in urine or blood of individuals were reported 91, 126.

Pomegranate Summary

Pomegranate is a potent antioxidant. This fruit is rich in flavonoids, anthocyanins, punicic acid, ellagitannins, alkaloids, fructose, sucrose, glucose, simple organic acids, and other components and has antiatherogenic, antihypertensive, and anti-inflammatory properties. Eventhough pomegranate can be used in the prevention and treatment of several types of cancer, cardiovascular disease, osteoarthritis, rheumatoid arthritis, and other diseases, mainly in laboratory animals and in petri dishes. We don’t have a lot of strong scientific evidence on the effects of pomegranate for people’s health. Many in vitro, animal and clinical trials have been carried out to examine and prove the therapeutic effects of these compounds, further human trials and studies are necessary to understand the therapeutic potentials of pomegranate 127.

- A 2012 clinical trial of about 100 dialysis patients suggested that pomegranate juice may help ward off infections. In the study, the patients who were given pomegranate juice three times a week for a year had fewer hospitalizations for infections and fewer signs of inflammation, compared with patients who got the placebo.

- Pomegranate extract in mouthwash may help control dental plaque, according to a small 2011 clinical trial with 30 healthy participants.

- Pomegranate may help improve some signs of heart disease but the research isn’t definitive.

Lastly, Federal agencies have taken action against companies (POM Pomegranate) selling pomegranate juice and supplements for deceptive advertising and making drug-like claims about the products. For more on this, view the NCCIH Director’s Page entitled Excessive Claims 128.

References- National Center for Complementary and Integrative Health. Pomegranate. https://nccih.nih.gov/health/pomegranate/at-a-glance

- Genetic relationships among wild pomegranate (Punica granatum) genotypes from Coruh Valley in Turkey. Ercisli S, Gadze J, Agar G, Yildirim N, Hizarci Y. Genet Mol Res. 2011 Mar 15; 10(1):459-64. https://www.ncbi.nlm.nih.gov/pubmed/21425096/

- Newman R. Sydney, Australia: Readhowyouwant; 2011. A wealth of phtochemicals. Pomegranate: The Most Medicinal Fruit p. 184.

- Newman RA, Lansky EP, Block ML. Pomegranate: The Most Medicinal Fruit. Laguna Beach, California: Basic Health Publications; 2007. -A Wealth of Phytochemicals; p. 120.

- United States Department of Agriculture, Agriculture Research Service. USDA Food Composition Databases. https://ndb.nal.usda.gov/ndb/

- Ko, K., Dadmohammadi, Y., & Abbaspourrad, A. (2021). Nutritional and Bioactive Components of Pomegranate Waste Used in Food and Cosmetic Applications: A Review. Foods (Basel, Switzerland), 10(3), 657. https://doi.org/10.3390/foods10030657

- Charalampia D., Koutelidakis A. From Pomegranate Processing By-Products to Innovative value added Func-tional Ingredients and Bio-Based Products with Several Applications in Food Sector. BAOJ Biotech. 2017;3:210.

- Gül H., Şen H. Effects of pomegranate seed flour on dough rheology and bread quality. CyTA J. Food. 2017;15:622–628. doi: 10.1080/19476337.2017.1327461

- Kaur S., Kumar S., Bhat Z.F. Utilization of pomegranate seed powder and tomato powder in the development of fi-ber-enriched chicken nuggets. Nutr. Food Sci. 2015;45:793–807. doi: 10.1108/NFS-05-2015-0066

- Verardo V., Garcia-Salas P., Baldi E., Segura-Carretero A., Fernandez-Gutierrez A., Caboni M.F. Pomegranate seeds as a source of nutraceutical oil naturally rich in bioactive lipids. Food Res. Int. 2014;65:445–452. doi: 10.1016/j.foodres.2014.04.044

- Viuda-Martos M, Fernández-López J, Pérez-Álvarez JA. Pomegranate and its Many Functional Components as Related to Human Health: A Review. Compr Rev Food Sci Food Saf. 2010 Nov;9(6):635-654. doi: 10.1111/j.1541-4337.2010.00131.x

- Zarfeshany, A., Asgary, S., & Javanmard, S. H. (2014). Potent health effects of pomegranate. Advanced biomedical research, 3, 100. https://doi.org/10.4103/2277-9175.129371

- Paul A., Radhakrishnan M. Pomegranate seed oil in food industry: Extraction, characterization, and applications. Trends Food Sci. Technol. 2020;105:273–283. doi: 10.1016/j.tifs.2020.09.014

- Khoddami A., Man Y.B.C., Roberts T.H. Physico-chemical properties and fatty acid profile of seed oils from pomegranate (Punica granatum L.) extracted by cold pressing. Eur. J. Lipid Sci. Technol. 2014;116:553–562. doi: 10.1002/ejlt.201300416

- Khajebishak Y., Payahoo L., Alivand M., Alipour B. Punicic acid: A potential compound of pomegranate seed oil in Type 2 diabetes mellitus management. J. Cell. Physiol. 2019;234:2112–2120. doi: 10.1002/jcp.27556

- Hora J.J., Maydew E.R., Lansky E.P., Dwivedi C. Chemopreventive Effects of Pomegranate Seed Oil on Skin Tumor Development in CD1 Mice. J. Med. Food. 2003;6:157–161. doi: 10.1089/10966200360716553

- Nekooeian A.A., Eftekhari M.H., Adibi S., Rajaeifard A. Effects of Pomegranate Seed Oil on Insulin Release in Rats with Type 2 Diabetes. Iran. J. Med. Sci. 2014;39:130–135.

- Aruna P., Venkataramanamma D., Singh A.K., Singh R. Health Benefits of Punicic Acid: A Review. Compr. Rev. Food Sci. Food Saf. 2015;15:16–27. doi: 10.1111/1541-4337.12171

- Ververi M., Goula A.M. Pomegranate peel and orange juice by-product as new biosorbents of phenolic compounds from olive mill wastewaters. Chem. Eng. Process. Process. Intensif. 2019;138:86–96. doi: 10.1016/j.cep.2019.03.010

- Amin N.K. Removal of direct blue-106 dye from aqueous solution using new activated carbons developed from pomegranate peel: Adsorption equilibrium and kinetics. J. Hazard. Mater. 2009;165:52–62. doi: 10.1016/j.jhazmat.2008.09.067

- Saadi W., Rodríguez-Sánchez S., Ruiz B., Souissi-Najar S., Ouederni A., Fuente E. Pyrolysis technologies for pomegranate (Punica granatum L.) peel wastes. Prospects in the bioenergy sector. Renew. Energy. 2019;136:373–382. doi: 10.1016/j.renene.2019.01.017

- Hossin F.L.A. Effect of Pomegranate (Punica granatum) Peels and It’s Extract on Obese Hypercholesterolemic Rats. Pak. J. Nutr. 2009;8:1251–1257. doi: 10.3923/pjn.2009.1251.1257

- Ismail T., Akhtar S., Riaz M., Ismail A. Effect of pomegranate peel supplementation on nutritional, organoleptic and stability properties of cookies. Int. J. Food Sci. Nutr. 2014;65:661–666. doi: 10.3109/09637486.2014.908170

- Colantuono A., Ferracane R., Vitaglione P. In vitro bioaccessibility and functional properties of polyphenols from pom-egranate peels and pomegranate peels-enriched cookies. Food Funct. 2016;7:4247–4258. doi: 10.1039/C6FO00942E

- Abid M., Yaich H., Hidouri H., Attia H., Ayadi M. Effect of substituted gelling agents from pomegranate peel on colour, textural and sensory properties of pomegranate jam. Food Chem. 2018;239:1047–1054. doi: 10.1016/j.foodchem.2017.07.006

- Yang X., Nisar T., Hou Y., Gou X., Sun L., Guo Y. Pomegranate peel pectin can be used as an effective emulsifier. Food Hydrocoll. 2018;85:30–38. doi: 10.1016/j.foodhyd.2018.06.042

- Pomegranate Council. http://www.pomegranates.org/index.php

- Pomegranate seed oil consumption during a period of high-fat feeding reduces weight gain and reduces type 2 diabetes risk in CD-1 mice. McFarlin BK, Strohacker KA, Kueht ML. Br J Nutr. 2009 Jul; 102(1):54-9. https://www.ncbi.nlm.nih.gov/pubmed/19079947/

- Activation of PPAR gamma and alpha by punicic acid ameliorates glucose tolerance and suppresses obesity-related inflammation. Hontecillas R, O’Shea M, Einerhand A, Diguardo M, Bassaganya-Riera J. J Am Coll Nutr. 2009 Apr; 28(2):184-95. https://www.ncbi.nlm.nih.gov/pubmed/19828904/

- Dietary effect of pomegranate seed oil rich in 9cis, 11trans, 13cis conjugated linolenic acid on lipid metabolism in obese, hyperlipidemic OLETF rats. Arao K, Wang YM, Inoue N, Hirata J, Cha JY, Nagao K, Yanagita T. Lipids Health Dis. 2004 Nov 9; 3():24. https://www.ncbi.nlm.nih.gov/pmc/articles/PMC534798/

- The influence of pomegranate fruit extract in comparison to regular pomegranate juice and seed oil on nitric oxide and arterial function in obese Zucker rats. de Nigris F, Balestrieri ML, Williams-Ignarro S, D’Armiento FP, Fiorito C, Ignarro LJ, Napoli C. Nitric Oxide. 2007 Aug; 17(1):50-4. https://www.ncbi.nlm.nih.gov/pubmed/17553710/

- Effect of pomegranate seed oil on hyperlipidaemic subjects: a double-blind placebo-controlled clinical trial. Mirmiran P, Fazeli MR, Asghari G, Shafiee A, Azizi F. Br J Nutr. 2010 Aug; 104(3):402-6. https://www.ncbi.nlm.nih.gov/pubmed/20334708/

- Effect of pomegranate juice on Angiotensin II-induced hypertension in diabetic Wistar rats. Mohan M, Waghulde H, Kasture S. Phytother Res. 2010 Jun; 24 Suppl 2():S196-203. https://www.ncbi.nlm.nih.gov/pubmed/20020514/

- The effects of polyphenol-containing antioxidants on oxidative stress and lipid peroxidation in Type 2 diabetes mellitus without complications. Fenercioglu AK, Saler T, Genc E, Sabuncu H, Altuntas Y. J Endocrinol Invest. 2010 Feb; 33(2):118-24. https://www.ncbi.nlm.nih.gov/pubmed/19834314/

- Gil MI, Tomás-Barberán FA, Hess-Pierce B, Holcroft DM, Kader AA. Antioxidant activity of pomegranate juice and its relationship with phenolic composition and processing. J Agric Food Chem. 2000;48:4581–9. https://www.ncbi.nlm.nih.gov/pubmed/11052704

- Tao X, Schulze-Koops H, Ma L, Cai J, Mao Y, Lipsky PE. Effects of Tripterygium wilfordii hook F extracts on induction of cyclooxygenase 2 activity and prostaglandin E2 production. Arthritis Rheum. 1998;41:130–8. https://www.ncbi.nlm.nih.gov/pubmed/9433878

- Loeser RF, Erickson EA, Long DL. Mitogen-activated protein kinases as therapeutic targets in osteoarthritis. Curr Opin Rheumatol. 2008;20:581–6. https://www.ncbi.nlm.nih.gov/pmc/articles/PMC2892710/

- Cerdá B, Cerón JJ, Tomás-Barberán FA, Espín JC. Repeated oral administration of high doses of the pomegranate ellagitannin punicalagin to rats for 37 days is not toxic. J Agric Food. 2003;51:3493–501. https://www.ncbi.nlm.nih.gov/pubmed/12744688

- Prescott SM, Fitzpatrick FA. Cyclooxygenase-2 and carcinogenesis. Biochim Biophys Acta. 2000;1470:69–78. https://www.ncbi.nlm.nih.gov/pubmed/10722929

- Kumar S, Votta BJ, Rieman DJ, Badger AM, Gowen M, Lee JC. IL-1- and TNF-induced bone resorption is mediated by p38 mitogen activated protein kinase. J Cell Physiol. 2001;187:294–303. https://www.ncbi.nlm.nih.gov/pubmed/11319753

- Jurenka JS. Therapeutic applications of pomegranate (Punica granatum L.): A review. Altern Med Rev. 2008 13:128–44. USDA 2010. Pomegranates, Raw. United States Department of Agriculture. https://www.nal.usda.gov/

- Dietary fiber: Essential for a healthy diet. https://www.mayoclinic.org/healthy-lifestyle/nutrition-and-healthy-eating/in-depth/fiber/art-20043983

- Al Juhaimi F., Özcan M.M., Ghafoor K. Characterization of pomegranate (Punica granatum L.) seed and oils. Eur. J. Lipid Sci. Technol. 2017;119:1700074. doi: 10.1002/ejlt.201700074

- Pamisetty A., Kumar K.A., Indrani D., Singh R.P. Rheological, physico-sensory and antioxidant properties of punicic acid rich wheat bread. J. Food Sci. Technol. 2020;57:253–262. doi: 10.1007/s13197-019-04055-3

- Pomegranate fruit juice for chemoprevention and chemotherapy of prostate cancer. Malik A, Afaq F, Sarfaraz S, Adhami VM, Syed DN, Mukhtar H. Proc Natl Acad Sci U S A. 2005 Oct 11; 102(41):14813-8. https://www.ncbi.nlm.nih.gov/pubmed/16192356/

- Rettig MB, Heber D, An J, Seeram NP, Rao JY, Liu H, et al. Pomegranate extract inhibits androgen-independent prostate cancer growth through a nuclear factor-kappaB-dependent mechanism. Mol Cancer Ther. 2008;7:2662–71. https://www.ncbi.nlm.nih.gov/pmc/articles/PMC2858627/

- Albrecht M, Jiang W, Kumi-Diaka J, Lansky EP, Gommersall LM, Patel A, et al. Pomegranate extracts potently suppress proliferation, xenograft growth, and invasion of human prostate cancer cells. J Med Food. 2004;7:274–83. https://www.ncbi.nlm.nih.gov/pubmed/15383219

- Kim ND, Mehta R, Yu W, Neeman I, Livney T, Amichay A, et al. Chemopreventive and adjuvant therapeutic potential of pomegranate (Punica granatum) for human breast cancer. Breast Cancer Res Treat. 2002;71:203–17. https://www.ncbi.nlm.nih.gov/pubmed/12002340

- Phase II study of pomegranate juice for men with rising prostate-specific antigen following surgery or radiation for prostate cancer. Clin Cancer Res. 2006 Jul 1;12(13):4018-26. http://clincancerres.aacrjournals.org/content/12/13/4018.long

- Freedland SJ, Carducci M, Kroeger N, et al. A Double Blind, Randomized, Neoadjuvant Study of the Tissue effects of POMx Pills in Men with Prostate Cancer Prior to Radical Prostatectomy. Cancer prevention research (Philadelphia, Pa). 2013;6(10):1120-1127. doi:10.1158/1940-6207.CAPR-12-0423. https://www.ncbi.nlm.nih.gov/pmc/articles/PMC3806642/

- Mehta R, Lansky EP. Breast cancer chemopreventive properties of pomegranate (Punica granatum) fruit extracts in a mouse mammary organ culture. Eur J Cancer Prev. 2004;13:345–8. https://www.ncbi.nlm.nih.gov/pubmed/15554563

- Khan N, Hadi N, Afaq F, Syed DN, Kweon MH, Mukhtar H. Pomegranate fruit extract inhibits prosurvival pathways in human A549 lung carcinoma cells and tumor growth in athymic nude mice. Carcinogenesis. 2007;28:163–73. https://www.ncbi.nlm.nih.gov/pubmed/16920736

- Adams LS, Seeram NP, Aggarwal BB, Takada Y, Sand D, Heber D. Pomegranate juice, total pomegranate ellagitannins, and punicalagin suppress inflammatory cell signaling in colon cancer cells. J Agric Food Chem. 2006;54:980–5. https://www.ncbi.nlm.nih.gov/pubmed/16448212

- Hora JJ, Maydew ER, Lansky EP, Dwivedi C. Chemopreventive effects of pomegranate seed oil on skin tumor development in CD1 mice. J Med Food. 2003;6:157–61. https://www.ncbi.nlm.nih.gov/pubmed/14585180

- Syed DN, Malik A, Hadi N, Sarfaraz S, Afaq F, Mukhtar H. Photochemopreventive effect of pomegranate fruit extract on UVA-mediated activation of cellular pathways in normal human epidermal keratinocytes. Photochem Photobiol. 2006;82:398–405. https://www.ncbi.nlm.nih.gov/pubmed/16613491

- Pacheco-Palencia LA, Noratto G, Hingorani L, Talcott ST, Mertens-Talcott SU. Protective effects of standardized pomegranate (Punica granatum L.) polyphenolic extract in ultraviolet-irradiated human skin fibroblasts. J Agric Food Chem. 2008;56:8434–41. https://www.ncbi.nlm.nih.gov/pubmed/18717570

- Stowe CB. The effects of pomegranate juice consumption on blood pressure and cardiovascular health. Complement Ther Clin Pract. 2011;17:113–5. https://www.ncbi.nlm.nih.gov/pubmed/21457902

- Mohan M, Waghulde H, Kasture S. Effect of pomegranate juice on Angiotensin II-induced hypertension in diabetic Wistar rats. Phytother Res. 2010;24:S196–203. https://www.ncbi.nlm.nih.gov/pubmed/20020514

- Aviram M, Rosenblat M, Gaitini D, Nitecki S, Hoffman A, Dornfeld L, et al. Pomegranate juice consumption for 3 years by patients with carotid artery stenosis reduces common carotid intima-media thickness, blood pressure and LDL oxidation. Clin Nutr. 2004;23:423–33. https://www.ncbi.nlm.nih.gov/pubmed/15158307

- Mirmiran P, Fazeli MR, Asghari G, Shafiee A, Azizi F. Effect of pomegranate seed oil on hyperlipidaemic subjects: A double-blind placebo-controlled clinical trial. Br J Nutr. 2010;104:402–6. https://www.ncbi.nlm.nih.gov/pubmed/20334708

- Aviram M, Dornfeld L, Rosenblat M, Volkova N, Kaplan M, Coleman R, et al. Pomegranate juice consumption reduces oxidative stress, atherogenic modifications to LDL, and platelet aggregation: Studies in humans and in atherosclerotic apolipoprotein E-deficient mice. Am J Clin Nutr. 2000;71:1062–76. https://www.ncbi.nlm.nih.gov/pubmed/10799367

- Kaplan M, Hayek T, Raz A, Coleman R, Dornfeld L, Vaya J, et al. Pomegranate juice supplementation to atherosclerotic mice reduces macrophage lipid peroxidation, cellular cholesterol accumulation and development of atherosclerosis. J Nutr. 2001;131:2082–9. https://www.ncbi.nlm.nih.gov/pubmed/11481398

- de Nigris F, Williams-Ignarro S, Sica V, Lerman LO, D’Armiento FP, Byrns RE, et al. Effects of a pomegranate fruit extract rich in punicalagin on oxidation-sensitive genes and eNOS activity at sites of perturbed shear stress and atherogenesis. Cardiovasc Res. 2007;73:414–23. https://www.ncbi.nlm.nih.gov/pubmed/17014835

- Esmaillzadeh A, Tahbaz F, Gaieni I, Alavi-Majd H, Azadbakht L. Cholesterol-lowering effect of concentrated pomegranate juice consumption in type II diabetic patients with hyperlipidemia. Int J Vitam Nutr Res. 2006;76:147–51. https://www.ncbi.nlm.nih.gov/pubmed/17048194

- Bagri P, Ali M, Aeri V, Bhowmik M, Sultana S. Antidiabetic effect of Punica granatum flowers: Effect on hyperlipidemia, pancreatic cells lipid peroxidation and antioxidant enzymes in experimental diabetes. Food Chem Toxicol. 2009;47:50–4. https://www.ncbi.nlm.nih.gov/pubmed/18950673

- Huang TH, Yang Q, Harada M, Li GQ, Yamahara J, Roufogalis BD, et al. Pomegranate flower extract diminishes cardiac fibrosis in Zucker diabetic fatty rats: Modulation of cardiac endothelin-1 and nuclear factor-kappaB pathways. J Cardiovasc Pharmacol. 2005;46:856–62. https://www.ncbi.nlm.nih.gov/pubmed/16306813

- Huang TH, Peng G, Kota BP, Li GQ, Yamahara J, Roufogalis BD, et al. Pomegranate flower improves cardiac lipid metabolism in a diabetic rat model: Role of lowering circulating lipids. Br J Pharmacol. 2005;145:767–74. https://www.ncbi.nlm.nih.gov/pmc/articles/PMC1576197/

- Hontecillas R, O’Shea M, Einerhand A, Diguardo M, Bassaganya-Riera J. Activation of PPAR gamma and alpha by punicic acid ameliorates glucose tolerance and suppresses obesity-related inflammation. J Am Coll Nutr. 2009;28:184–95. https://www.ncbi.nlm.nih.gov/pubmed/19828904

- Lei F, Zhang XN, Wang W, Xing DM, Xie WD, Su H, DU LJ. Evidence of anti-obesity effects of the pomegranate leaf extract in high-fat diet induced obese mice. Int J Obes (Lond) 2007;31:1023–9. https://www.ncbi.nlm.nih.gov/pubmed/17299386

- Vroegrijk IO, van Diepen JA, van den Berg S, Westbroek I, Keizer H, Gambelli L. Pomegranate Seed Oil, a rich source of Punicic Acid, prevents diet-induced obesity and insulin resistance in mice. Food Chem Toxicol. 2011;49:1426–30. https://www.ncbi.nlm.nih.gov/pubmed/21440024

- Xu KZ, Zhu C, Kim MS, Yamahara J, Li Y. Pomegranate flower ameliorates fatty liver in an animal model of type 2 diabetes and obesity. J Ethnopharmacol. 2009;123:280–7. https://www.ncbi.nlm.nih.gov/pubmed/19429373

- de Nigris F, Balestrieri ML, Williams-Ignarro S, D’Armiento FP, Fiorito C, Ignarro LJ, et al. The influence of pomegranate fruit extract in comparison to regular pomegranate juice and seed oil on nitric oxide and arterial function in obese Zucker rats. Nitric Oxide. 2007;17:50–4. https://www.ncbi.nlm.nih.gov/pubmed/17553710

- Kahya V, Meric A, Yazici M, Yuksel M, Midi A, Gedikli O. Antioxidant effect of pomegranate extract in reducing acute inflammation due to myringotomy. J Laryngol Otol. 2011;1:370–5. https://www.ncbi.nlm.nih.gov/pubmed/21349238

- González-Sarrías A, Larrosa M, Tomás-Barberán FA, Dolara P, Espín JC. NF-kappaB-dependent anti-inflammatory activity of urolithins, gut microbiota ellagic acid-derived metabolites, in human colonic fibroblasts. Br J Nutr. 2010;104:503–12. https://www.ncbi.nlm.nih.gov/pubmed/20338073

- Boussetta T, Raad H, Lettéron P, Gougerot-Pocidalo MA, Marie JC, Driss F, et al. Punicic acid a conjugated linolenic acid inhibits TNFalpha-induced neutrophil hyperactivation and protects from experimental colon inflammation in rats. PLoS One. 2009;4:e6458. https://www.ncbi.nlm.nih.gov/pmc/articles/PMC2714468/

- Katz SR, Newman RA, Lansky EP. Punica granatum: Heuristic treatment for diabetes mellitus. J Med Food. 2007;10:213–7. https://www.ncbi.nlm.nih.gov/pubmed/17651054

- Rock W, Rosenblat M, Miller-Lotan R, Levy AP, Elias M, Aviram M. Consumption of wonderful variety pomegranate juice and extract by diabetic patients increases paraoxonase 1 association with high-density lipoprotein and stimulates its catalytic activities. J Agric Food Chem. 2008;56:8704–13. https://www.ncbi.nlm.nih.gov/pubmed/18759451

- Fenercioglu AK, Saler T, Genc E, Sabuncu H, Altuntas Y. The effects of polyphenol-containing antioxidants on oxidative stress and lipid peroxidation in Type 2 diabetes mellitus without complications. J Endocrinol Invest. 2010;33:118–24. https://www.ncbi.nlm.nih.gov/pubmed/19834314

- Houston D.M., Bugert J., Denyer S.P., Heard C.M. Anti-inflammatory activity of Punica granatum L. (Pomegranate) rind extracts applied topically to ex vivo skin. Eur. J. Pharm. Biopharm. 2017;112:30–37. doi: 10.1016/j.ejpb.2016.11.014

- Houston D.M., Robins B., Bugert J.J., Denyer S.P., Heard C.M. In vitro permeation and biological activity of punicalagin and zinc (II) across skin and mucous membranes prone to Herpes simplex virus infection. Eur. J. Pharm. Sci. 2017;96:99–106. doi: 10.1016/j.ejps.2016.08.013

- Houston D.M., Bugert J.J., Denyer S.P., Heard C.M. Potentiated virucidal activity of pomegranate rind extract (PRE) and punicalagin against Herpes simplex virus (HSV) when co-administered with zinc (II) ions, and antiviral activity of PRE against HSV and aciclovir-resistant HSV. PLoS ONE. 2017;12:e0179291

- Marchiori M.C.L., Rigon C., Camponogara C., Oliveira S.M., Cruz L. Hydrogel containing silibinin-loaded pomegranate oil based nanocapsules exhibits anti-inflammatory effects on skin damage UVB radiation-induced in mice. J. Photochem. Photobiol. B Biol. 2017;170:25–32. doi: 10.1016/j.jphotobiol.2017.03.015

- Baccarin T., Mitjans M., Ramos D., Lemos-Senna E., Vinardell M.P. Photoprotection by Punica granatum seed oil nanoemulsion entrapping polyphenol-rich ethyl acetate fraction against UVB-induced DNA damage in human keratinocyte (HaCaT) cell line. J. Photochem. Photobiol. B Biol. 2015;153:127–136. doi: 10.1016/j.jphotobiol.2015.09.005

- Liu C., Guo H., DaSilva N.A., Li D., Zhang K., Wan Y., Gao X.H., Chen H.D., Seeram N.P., Ma H. Pomegranate (Punica granatum) phenolics ameliorate hydrogen peroxide-induced oxidative stress and cyto-toxicity in human keratinocytes. J. Funct. Foods. 2019;54:559–567. doi: 10.1016/j.jff.2019.02.015

- Rasheed Z, Akhtar N, Haqqi TM. Pomegranate extract inhibits the interleukin-1b-induced activation of MKK-3, p38a-MAPK and transcription factor RUNX-2 in human osteoarthritis chondrocytes -Arthritis Res Ther. 2010;12:195. https://www.ncbi.nlm.nih.gov/pmc/articles/PMC2991031/

- Lee JC, Laydon JT, McDonnell PC, Gallagher TF, Kumar S, Green D. A protein kinase involved in the regulation of inflammatory cytokine biosynthesis. Nature. 1994;372:739–46. https://www.ncbi.nlm.nih.gov/pubmed/7997261

- Hayden MS, Ghosh S. Signaling to NF-B. Genes Dev. 2004;18:2195. https://www.ncbi.nlm.nih.gov/pubmed/15371334

- Schieven GL. The biology of p38 kinase: A central role in inflammation. Curr Top Med Chem. 2005;5:921–8. https://www.ncbi.nlm.nih.gov/pubmed/16178737

- Shukla M, Gupta K, Rasheed Z, et al. Consumption of hydrolyzable tannins-rich pomegranate extract suppresses inflammation and joint damage in rheumatoid arthritis. Nutrition. 2008;24(7–8):733–743. https://www.ncbi.nlm.nih.gov/pubmed/18490140

- Shukla M, Gupta K, Rasheed Z, Khan KA, Haqqi TM. Bioavailable constituents/metabolites of pomegranate (Punica granatum L) preferentially inhibit COX2 activity ex vivo and IL-1beta-induced PGE2 production in human chondrocytes in vitro. J Inflamm (Lond) 2008;5:9. https://www.ncbi.nlm.nih.gov/pmc/articles/PMC2438359/

- Jurenka JS. Therapeutic applications of pomegranate (Punica granatum L.): A review. [Accessed September 2010];Altern Med Rev. 2008 13:128–44. USDA 2010.

- Lansky E, Shubert S, Neeman I. Pharmacological and therapeutic properties of pomegranate. Israel: CIHEAM-Options Mediterraneennes; 2004;42:231–5.

- Satish S, Mohana D, Ranhavendra M, Raveesha K. Antifungal activity of some plant extracts against important seed borne pathogens of Aspergillus sp. J Agric Sci Technol. 2007;3:109–19.

- Mithun P, Prashant G, Murlikrishna K, Shivakumar K, Chandu G. Antifungal efficacy of Punica granatum, Acacia nilotica, Cuminum cyminum and Foeniculum vulgare on Candida albicans: An in vitro study. Indian J Dent Res. 2010;21:334–6. https://www.ncbi.nlm.nih.gov/pubmed/20930339

- Höfling JF, Anibal PC, Obando-Pereda GA, Peixoto IA, Furletti VF, Foglio MA, Goncalves RB. Antimicrobial potential of some plant extracts against Candida species. Braz J Biol. 2010;70:1065–8. https://www.ncbi.nlm.nih.gov/pubmed/21180915

- Ferrara AM. Treatment of hospital-acquired pneumonia caused by methicillin-resistant Staphylococcus aureus. Int J Antimicrob Agents. 2007;30:19–24. https://www.ncbi.nlm.nih.gov/pubmed/17475449

- Wenzel RP, Bearman G, Edmond MB. Community-acquired methicillin-resistant staphylococcus aureus (MRSA): New issues for infection control. Int J Antimicrob Agents. 2007;30:210–2. https://www.ncbi.nlm.nih.gov/pubmed/17566712

- Gould SW, Fielder MD, Kelly AF, Naughton DP. Anti-microbial activities of pomegranate rind extracts: Enhancement by cupric sulphate against clinical isolates of S. aureus, MRSA and PVL positive CA-MSSA. BMC Complement Altern Med. 2009;9:23. https://www.ncbi.nlm.nih.gov/pmc/articles/PMC2724405/

- Sharma M, Li L, Celver J, Killian C, Kovoor A, Seeram NP. Effects of fruit ellagitannin extracts, ellagic acid, and their colonic metabolite, urolithin A, on Wnt signaling. J Agric Food Chem. 2010;58:3965–9. https://www.ncbi.nlm.nih.gov/pmc/articles/PMC2850963/

- Kanlayavattanakul M., Chongnativisit W., Chaikul P., Lourith N. Phenolic-rich Pomegranate Peel Extract: In Vitro, Cellular, and In Vivo Activities for Skin Hy-perpigmentation Treatment. Planta Med. 2020;86:749–759. doi: 10.1055/a-1170-7785

- Afaq F, Zaid MA, Khan N, Dreher M, Mukhtar H. Protective effect of pomegranate-derived products on UVB-mediated damage in human reconstituted skin. Exp Dermatol. 2009;18:553–61. https://www.ncbi.nlm.nih.gov/pmc/articles/PMC3004287/

- Bae JY, Choi JS, Kang SW, Lee YJ, Park J, Kang YH. Dietary compound ellagic acid alleviates skin wrinkle and inflammation induced by UV-B irradiation. Exp Dermatol. 2010;19:e182–90. https://www.ncbi.nlm.nih.gov/pubmed/20113347

- Kumagai Y., Nakatani S., Onodera H., Nagatomo A., Nishida N., Matsuura Y., Kobata K., Wada M. Anti-Glycation Effects of Pomegranate (Punica granatum L.) Fruit Extract and Its Components in Vivo and in Vitro. J. Agric. Food Chem. 2015;63:7760–7764. doi: 10.1021/acs.jafc.5b02766

- Mirsane S, Mirsane S. Benefits of ellagic acid from grapes and pomegranates against colorectal cancer. Caspian J Intern Med. 2017 Summer;8(3):226-227. doi: 10.22088/cjim.8.3.226

- Turrini F., Malaspina P., Giordani P., Catena S., Zunin P., Boggia R. Traditional Decoction and PUAE Aqueous Extracts of Pomegranate Peels as Potential Low-Cost An-ti-Tyrosinase Ingredients. Appl. Sci. 2020;10:2795. doi: 10.3390/app10082795

- Yoshimura M., Watanabe Y., Kasai K., Yamakoshi J., Koga T. Inhibitory Effect of an Ellagic Acid-Rich Pomegranate Extract on Tyrosinase Activity and Ultravio-let-Induced Pigmentation. Biosci. Biotechnol. Biochem. 2005;69:2368–2373. doi: 10.1271/bbb.69.2368

- Bogdan C., Iurian S., Tomuta I., Moldovan M.L. Improvement of skin condition in striae distensae: Development, characterization and clinical efficacy of a cosmetic product containing Punica granatum seed oil and Croton lechleri resin extract. Drug Des. Dev. Ther. 2017;11:521–531. doi: 10.2147/DDDT.S128470

- Baltazar D., Marto J., Berger T., Pinto P., Ribeiro H.M. The antiageing efficacy of donkey milk in combination with pomegranate extract and UV protection: A traditional ingredient in a modern formulation. Monogr. Spec. Issue Cosmet. Act. Ingred. H&PC Today Househ. Pers. Care Today. 2017;12:30–32.

- Bae J.-Y., Choi J.-S., Kang S.-W., Lee Y.-J., Park J., Kang Y.-H. Dietary compound ellagic acid alleviates skin wrinkle and inflammation induced by UV-B irradiation. Exp. Dermatol. 2010;19:e182–e190. doi: 10.1111/j.1600-0625.2009.01044.x

- Rout S., Banerjee R. Free radical scavenging, anti-glycation and tyrosinase inhibition properties of a polysaccharide frac-tion isolated from the rind from Punica granatum. Bioresour. Technol. 2007;98:3159–3163. doi: 10.1016/j.biortech.2006.10.011

- Yagi M., Parengkuan L., Sugimura H., Shioya N., Matsuura Y., Nishida N., Nagatomo A., Yonei Y. Anti-glycation effect of pomegranate (Punica granatum L.) extract: An open clinical study. Glycative Stress Res. 2014;1:060–067

- Castiel I., Gueniche A. Non-Therapeutic Cosmetic Use of at Least One Pomegranate Extract, as Agent for Firming Skin of a Subject, Who Has Weight Modification Prior to and/or After an Aesthetic Surgery and to Prevent and/or Treat Sagging Skin, in Espcenet. FR2967063A1. 2012 May 11

- Wilson K. Lip Gloss. US 2012/0288319 A1. 2012 Nov 15

- Kasai K., Yoshimura M., Koga T., Arii M., Kawasaki S. Effects of oral administration of ellagic acid-rich pomegranate extract on ultraviolet-induced pigmentation in the human skin. J. Nutr. Sci. Vitaminol. 2006;52:383–388. doi: 10.3177/jnsv.52.383

- Lukiswanto B.S., Miranti A., Sudjarwo S.A., Primarizky H., Yuniarti W.M. Evaluation of wound healing potential of pomegranate (Punica granatum) whole fruit extract on skin burn wound in rats (Rattus norvegicus) J. Adv. Vet. Anim. Res. 2019;6:202–207. doi: 10.5455/javar.2019.f333

- Yuniarti W.M., Primarizky H., Lukiswanto B.S. The activity of pomegranate extract standardized 40% ellagic acid during the healing process of incision wounds in albino rats (Rattus norvegicus) Vet. World. 2018;11:321–326. doi: 10.14202/vetworld.2018.321-326

- Mo J., Panichayupakaranant P., Kaewnopparat N., Nitiruangjaras A., Reanmongkol W. Wound healing activities of standardized pomegranate rind extract and its major antioxidant ellagic acid in rat dermal wounds. J. Nat. Med. 2014;68:377–386. doi: 10.1007/s11418-013-0813-9

- Bhadbhade SJ, Acharya AB, Rodrigues SV, Thakur SL. The antiplaque efficacy of pomegranate mouthrinse. Quintessence Int. 2011;42:29–36. https://www.ncbi.nlm.nih.gov/pubmed/21206931

- Menezes SM, Cordeiro LN, Viana GS. Punica granatum (pomegranate) extract is active against dental plaque. J Herb Pharmacother. 2006;6:79–92. https://www.ncbi.nlm.nih.gov/pubmed/17182487

- Promprom W, Kupittayanant P, Indrapichate K, Wray S, Kupittayanant S. The effects of pomegranate seed extract and beta-sitosterol on rat uterine contractions. Reprod Sci. 2010;17:288–96. https://www.ncbi.nlm.nih.gov/pubmed/19966214

- Türk G, Sönmez M, Aydin M, Yüce A, Gür S, Yüksel M, et al. Effects of pomegranate juice consumption on sperm quality, spermatogenic cell density, antioxidant activity and testosterone level in male rats. Clin Nutr. 2008;27:289–96. https://www.ncbi.nlm.nih.gov/pubmed/18222572

- Hartman RE, Shah A, Fagan AM, Schwetye KE, Parsadanian M, Schulman RN, et al. Pomegranate juice decreases amyloid load and improves behavior in a mouse model of Alzheimer’s disease. Neurobiol Dis. 2006;24:506–15. https://www.ncbi.nlm.nih.gov/pubmed/17010630