Psoriatic arthritis

Psoriatic arthritis is a form of arthritis that affects some people who have psoriasis 1. Psoriasis is a skin disease that causes itchy or sore patches of thick, red skin with silvery scales. You usually get them on your elbows, knees, scalp, back, face, palms and feet, but they can show up on other parts of your body. Psoriatic arthritis is usually negative for rheumatoid factor (RF) and hence classified as one of the seronegative spondyloarthropathies. Men and women are equally affected by psoriatic arthritis. The symptoms of psoriatic arthritis come and go but it is a lifelong condition that is usually progressive.

Up to 30 percent of people with psoriasis also develop psoriatic arthritis 2. Psoriatic arthritis causes pain, stiffness, and swelling of your joints. Psoriatic arthritis is often mild, but can sometimes be serious and affect many joints. The joint and skin problems don’t always happen at the same time. Most people develop psoriasis first and are later diagnosed with psoriatic arthritis sometimes by many years, but the joint problems (arthritis) can sometimes begin before skin lesions appear.

When arthritis symptoms occur with psoriasis, it is called psoriatic arthritis (psoriatic spondyloarthropathy). In these cases, the joints at the end of your fingers are most commonly affected, causing inflammation and pain, but other joints like the wrists, knees, and ankles can also become involved. This is usually accompanied by symptoms in the fingernails and toenails, ranging from small pits in the nails to nearly complete destruction and crumbling as seen in reactive arthritis or fungal infections.

The joints most often affected are:

- The outer joints of the fingers or toes.

- Wrists.

- Knees.

- Ankles.

- Lower back.

Joint pain, stiffness and swelling are the main symptoms of psoriatic arthritis. They can affect any part of your body, including your fingertips and spine, and can range from relatively mild to severe. In both psoriasis and psoriatic arthritis, disease flares may alternate with periods of remission.

Onset of psoriasis and arthritis are as follows:

- Psoriasis appears to precede the onset of psoriatic arthritis in 60-80% of patients (occasionally by as many as 20 years, but usually by less than 10 years)

- In as many as 15-20% of patients, arthritis appears before the psoriasis

- Occasionally, arthritis and psoriasis appear simultaneously

In some cases, patients may experience only stiffness and pain, with few objective findings. In most patients, the musculoskeletal symptoms are insidious in onset, but an acute onset has been reported in one third of all patients.

Psoriatic arthritis is more common in Caucasians than African Americans or Asian Americans. The disease typically begins between the ages of 30 and 50, but can begin in childhood 3.

People with psoriasis who are more likely to subsequently get arthritis include those with the following characteristics 4:

- Psoriatic nail disease

- Flexural psoriasis, scalp psoriasis or post-auricular psoriasis

- Obesity

- Smoker

- Elevated C-reactive protein (CRP) at baseline.

About 20 percent of patients with psoriatic arthritis will develop spinal involvement, which is called psoriatic spondylitis 5. Inflammation of the spine can lead to complete fusion, as in ankylosing spondylitis or affect only certain areas such as the lower back or neck. Patients who are HLA-B27 positive are more likely than others to have their disease progress to the spine 5.

Psoriatic arthritis and ankylosing spondylitis are considered genetically and clinically related because both are inflammatory rheumatic diseases linked to the HLA-B27 gene 5. HLA-B27 is a powerful predisposing gene associated with several rheumatic diseases. The HLA-B27 gene itself does not cause disease, but can make people more susceptible. While a number of genes are linked to psoriatic arthritis, the highest predictive value is noted with HLA-B27.

Your doctor will do a physical exam and imaging tests to diagnose psoriatic arthritis. At the present time there is no cure for psoriatic arthritis, but medicines can help control inflammation and pain. In rare cases, you might need surgery to repair or replace damaged joints. Without treatment, psoriatic arthritis can be disabling.

There’s no cure for psoriatic arthritis. Treatment is aimed at controlling symptoms and preventing joint damage.

Psoriatic arthritis key facts:

- Psoriatic arthritis is chronic arthritis. In some people, it is mild, with just occasional flare ups. In other people, it is continuous and can cause joint damage if it is not treated. Early diagnosis is important to avoid damage to joints.

- Psoriatic arthritis typically occurs in people with skin psoriasis, but it can occur in people without skin psoriasis, particularly in those who have relatives with psoriasis.

- Psoriatic arthritis typically affects the large joints, especially those of the lower extremities, small joints of the fingers and toes, and can affect the spine and sacroiliac joints of the pelvis. Eyes, tendons, gastrointestinal system, and nails can also be involved.

- For most people, appropriate treatments will relieve pain, protect the joints, and maintain mobility. Physical activity helps maintain joint movement.

Figure 1. Psoriatic arthritis rash

Who gets psoriatic arthritis?

Psoriatic arthritis has an incidence of approximately 6 per 100,000 per year and a prevalence of about 1–2 per 1000 in the general population 4. Estimates of the prevalence of psoriatic arthritis among patients with psoriasis range between 4 and 30 per cent. In most patients, arthritis appears 10 years after the first signs of skin psoriasis 4. The first signs of psoriatic arthritis usually occur between the ages of 30 and 50 years of age 4. In approximately 13–17% of cases, arthritis precedes the skin disease 4.

Psoriatic arthritis symptoms

Both psoriatic arthritis and psoriasis are chronic diseases that get worse over time, but you may have periods when your symptoms improve or go into remission alternating with times when symptoms become worse.

Psoriatic arthritis can affect joints on just one side or on both sides of your body. The signs and symptoms of psoriatic arthritis often resemble those of rheumatoid arthritis. Both diseases cause joints to become painful, swollen and warm to the touch.

The symptoms of psoriatic arthritis can vary from person to person and change in severity. Skin symptoms typically (but not always) appear before the joints become involved, sometimes up to 10 years before. Without treatment, many of these symptoms can lead to progressive, permanent joint damage 5.

Symptoms of psoriatic arthritis include:

- Joint pain and swelling that may come and go and may be accompanied by redness and warmth.

- Tenderness where muscles or ligaments attach to the bones, particularly the heel and bottom of the foot.

- Inflammation of the spinal column, called spondylitis, which can cause pain and stiffness in the neck and lower back.

- Morning stiffness.

- Reduced range of motion of the joints.

- Back pain and stiffness, primarily in the lower back, neck, and upper back.

- Painful, often throbbing joints.

- Swollen fingers and toes. Psoriatic arthritis can cause a painful, sausage-like swelling of your fingers and toes. You may also develop swelling and deformities in your hands and feet before having significant joint symptoms.

- Thickness and reddening of the skin with flaky, silver white patches called scales.

- Pitting of the nails or separation from the nail bed and/or discoloration of the fingernails or toenails, which occur in almost all patients;

- Tiredness or generalized fatigue.

- Pink eye, inflammation, or infection of the membrane lining the eyelid and part of the eyeball that can cause redness, pain, blurred vision, and sensitivity to light. Thirty percent of psoriatic arthritis patients have conjunctivitis, and seven percent have iritis.

- Foot pain. Psoriatic arthritis can also cause pain at the points where tendons and ligaments attach to your bones — especially at the back of your heel (Achilles tendinitis) or in the sole of your foot (plantar fasciitis).

- Lower back pain. Some people develop a condition called spondylitis as a result of psoriatic arthritis. Spondylitis mainly causes inflammation of the joints between the vertebrae of your spine and in the joints between your spine and pelvis (sacroiliitis).

Psoriatic arthritis develops after skin psoriasis in approximately 75% of patients 4. Remaining patients have either a simultaneous onset of skin and joint psoriasis (10%), or joint symptoms precede any skin problem (15%). The severity of the skin disease does not predict the severity of the joint disease 4.

Plaque psoriasis is the most common form of skin psoriasis seen with psoriatic arthritis. Joint symptoms may be exacerbated by a flare in skin psoriasis but quite commonly the skin symptoms behave independently of joint symptoms. Most people with psoriatic arthritis have mild psoriasis.

Figure 2. Psoriatic arthritis fingers

Note: Swelling and deformity of the metacarpophalangeal and distal interphalangeal joints in a patient with psoriatic arthritis.

Figure 3. Psoriatic arthritis hands

Note: Severe psoriatic arthritis showing involvement of the distal interphalangeal joints, distal flexion deformity, and telescoping of the left third, fourth, and fifth digits due to destruction of joint tissue.

Psoriatic arthritis causes

The exact cause of psoriatic arthritis is not known, but the main contributing factors to the development of psoriatic arthritis are a genetic predisposition, immune factors and the environment 4. Psoriatic arthritis occurs when your body’s immune system begins to attack healthy cells and tissue. The abnormal immune response causes inflammation in your joints as well as overproduction of skin cells.

It’s not entirely clear why the immune system turns on healthy tissue, but it seems likely that both genetic and environmental factors play a role. Up to 40 percent of people with psoriatic arthritis have a family history of either psoriasis or psoriatic arthritis 5. Researchers have discovered certain genetic markers that appear to be associated with psoriatic arthritis — of those with psoriatic arthritis, 40% have a family member with psoriasis or arthritis, suggesting heredity may play a role. If an identical twin has psoriatic arthritis, there is a 75 percent chance that the other twin will have it as well 5.

Psoriatic arthritis can also result from an infection that activates the immune system. While psoriasis itself is not infectious, it might be triggered by a streptococcal throat infection, commonly known as strep throat 6.

Physical trauma or something in the environment — such as a viral or bacterial infection — may trigger psoriatic arthritis in people with an inherited tendency.

Genetic factors

As in psoriasis of the skin, many patients with psoriatic arthritis may have a familial tendency toward the condition. A twin study found that arthritis was as common in dizygotic (fraternal) twins as in monozygotic (identical) twins so unknown environmental factors may also be important. First-degree relatives of patients with psoriatic arthritis have a 50-fold increased risk of developing psoriatic arthritis compared with the general population. It is unclear whether this is due to a genetic basis of psoriasis alone, or whether there is a special genetic predisposition to arthritis as well.

Immune factors

Psoriatic arthritis occurs as a result of abnormal interaction between the immune system and the joints. People with psoriatic arthritis seem to have an overactive immune system as evidenced by raised inflammatory markers, increased antibodies and T-lymphocytes.

Activated T cells (in particular CD8+ T cells) have generally been found in the skin and joints of patients with psoriatic arthritis. Several studies have demonstrated that pro-inflammatory cytokines secreted from activated T cells (especially tumour necrosis factor alpha (TNF-α), IL-17, IL-18 and IL-23) induce proliferation and activation of synovial and epidermal fibroblasts. CD8+, IL-17+ cells, natural killer (NK) cells and innate lymphoid (ILC3) cells are present in high concentrations in the synovial fluid and skin lesions in patients with psoriatic arthritis.

Environmental factors

Environmental factors implicated in the pathogenesis of psoriatic arthritis include infections (bacterial infections such as streptococci and Borrelia burgdorferi, the cause of Lyme disease; and viral infections such as rubella), trauma (Koebner phenomenon), moving to a new house, recurrent oral ulcers, obesity and bone fractures.

An inverse association with smoking has also been reported in HLA-C*06 allele negative patients 4.

Risk factors for Psoriatic arthritis

Several factors can increase your risk of psoriatic arthritis, including:

- Psoriasis. Having psoriasis is the single greatest risk factor for developing psoriatic arthritis. People who have psoriasis lesions on their nails are especially likely to develop psoriatic arthritis.

- Your family history. Many people with psoriatic arthritis have a parent or a sibling with the disease.

- Your age. Although anyone can develop psoriatic arthritis, it occurs most often in adults between the ages of 30 and 50.

Psoriatic arthritis complications

The impact of psoriatic arthritis depends on the joints involved and the severity of symptoms. A small percentage of people with psoriatic arthritis develop arthritis mutilans — a severe, painful and disabling form of the disease. Over time, arthritis mutilans destroys the small bones in your hands, especially the fingers, leading to permanent deformity and disability.

People who have psoriatic arthritis sometimes also develop eye problems such as pinkeye (conjunctivitis) or uveitis, which can cause painful, reddened eyes and blurred vision. They also are at higher risk of cardiovascular disease.

Fatigue and anemia are common. Some psoriatic arthritis patients also experience mood changes. Treating the arthritis and reducing the levels of inflammation helps with these problems. People with psoriasis are slightly more likely to develop high blood pressure, high cholesterol, obesity or diabetes. Maintaining a healthy weight and treating high blood pressure and cholesterol are also important aspects of treatment.

Figure 4. Psoriatic Arthritis Mutilans

Psoriatic arthritis diagnosis

If you have psoriasis and start to develop joint pain, it’s important to see your doctor. Early diagnosis and treatment of psoriatic arthritis can help prevent joint damage.

Diagnosing psoriatic arthritis can be tricky, primarily because it shares similar symptoms with other diseases such as osteoarthritis, rheumatoid arthritis, and gout. Because of this, misdiagnosis can often be a problem. Early diagnosis, however, is important because long-term joint damage can be warded off better in the first few months after symptoms arise.

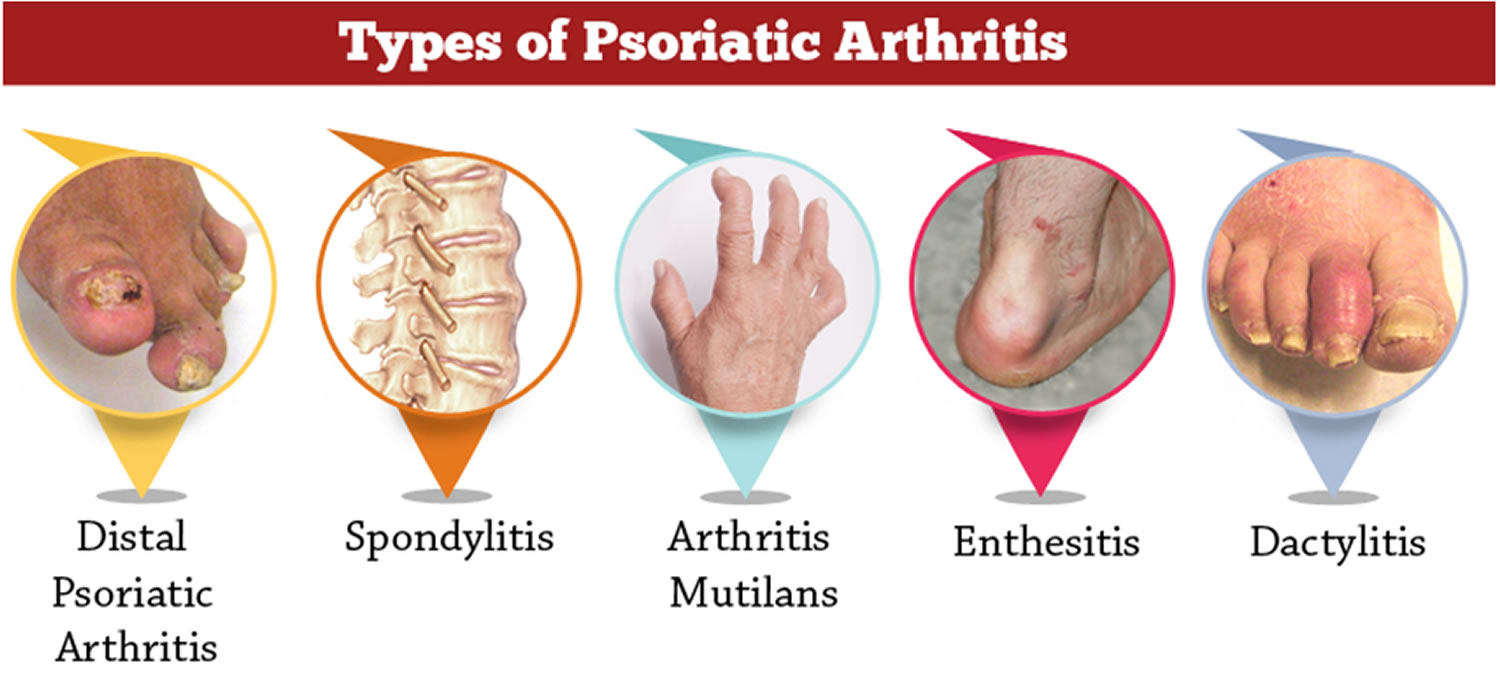

The diagnosis of psoriatic arthritis is based on symptoms, an examination of skin and joints and compatible X-ray findings 4. Psoriatic arthritis may present with tendinitis, enthesitis or dactylitis, rather than swollen joints.

Classification criteria, such as CASPAR criteria, are mainly used for research purposes. Several screening questionnaires have also been developed, such as Toronto Psoriatic Arthritis Screen (ToPAS2), to help to identify patients with psoriatic arthritis.

Although there is no test for psoriatic arthritis, your doctor may do the following to diagnosis you with the condition:

- Ask you about your medical and family history.

- Give you a physical exam.

- Take samples of blood or joint fluid for a laboratory test.

- Take x-rays

- Magnetic resonance imaging (MRI). Plain X-rays can help pinpoint changes in the joints that occur in psoriatic arthritis but not in other arthritic conditions. MRI utilizes radio waves and a strong magnetic field to produce very detailed images of both hard and soft tissues in your body. This type of imaging test may be used to check for problems with the tendons and ligaments in your feet and lower back. Magnetic resonance imaging studies are particularly sensitive for detecting sacroiliitic synovitis, enthesitis, and erosions; can also be used with gadolinium to increase sensitivity. MRI may show inflammation in the small joints of the hands, involving the collateral ligaments and soft tissues around the joint capsule, a finding not seen in persons with rheumatoid arthritis.

Physical examination

Findings on physical examination are as follows:

- Enthesopathy or enthesitis, reflecting inflammation at tendon or ligament insertions into bone, is observed more often at the attachment of the Achilles tendon and the plantar fascia to the calcaneus with the development of insertional spurs

- Dactylitis with sausage digits is seen in as many as 35% of patients

- Skin lesions include scaly, erythematous plaques; guttate lesions; lakes of pus; and erythroderma

- Psoriasis may occur in hidden sites, such as the scalp (where psoriasis frequently is mistaken for dandruff), perineum, intergluteal cleft, and umbilicus

Psoriatic nail changes, which may be a solitary finding in patients with psoriatic arthritis, may include the following:

- Beau lines

- Leukonychia

- Onycholysis

- Oil spots

- Subungual hyperkeratosis

- Splinter hemorrhages

- Spotted lunulae

- Transverse ridging

- Cracking of the free edge of the nail

- Uniform nail pitting

Extra-articular features are observed less frequently in patients with psoriatic arthritis than in those with rheumatoid arthritis but may include the following:

- Synovitis affecting flexor tendon sheaths, with sparing of the extensor tendon sheath

- Subcutaneous nodules are rare

- Ocular involvement may occur in 30% of patients, including conjunctivitis in 20% and acute anterior uveitis in 7%; in patients with uveitis, 43% have sacroiliitis

Blood tests

There are no diagnostic blood tests for psoriatic arthritis but tests may be done to help confirm the diagnosis and rule out other causes 7.

- Rheumatoid factor (RF). Rheumatoid factor (RF) is an antibody that’s often present in the blood of people with rheumatoid arthritis, but rheumatoid factor is usually negative but may be positive in up to 10% of patients with psoriatic arthritis. For that reason, this test can help your doctor distinguish between the two conditions.

- Anti-CCP (anti-cyclic citrullinated peptide) is also usually negative but may be positive in up to 7% of patients with psoriatic arthritis.

- Markers of inflammation, ESR (erythrocyte sedimentation rate) and CRP, may reflect the severity of the inflammation in the joints.

- HLA-B27 testing. HLA-B27 is a specific protein involved with immune regulation. 57% of psoriatic arthritis patients with axial involvement are positive for HLA-B27

- Joint fluid test. Using a needle, your doctor can remove a small sample of fluid from one of your affected joints — often the knee. Uric acid crystals in your joint fluid may indicate that you have gout rather than psoriatic arthritis.

The most characteristic laboratory abnormalities in patients with psoriatic arthritis are as follows:

- Elevations of the erythrocyte sedimentation rate (ESR) and C-reactive protein level

- Negative rheumatoid factor in 91-95% of patients

- In 10-20% of patients with generalized skin disease, the serum uric acid concentration may be increased

- Low levels of circulating immune complexes have been detected in 56% of patients

- Serum immunoglobulin A levels are increased in two thirds of patients

- Synovial fluid is inflammatory, with cell counts ranging from 5000-15,000/µL and with more than 50% of cells being polymorphonuclear leukocytes; complement levels are either within reference ranges or increased, and glucose levels are within reference ranges

Imaging studies

Radiologic features have helped to distinguish psoriatic arthritis from other causes of polyarthritis. In general, the common subtypes of psoriatic arthritis, such as asymmetrical oligoarthritis and symmetrical polyarthritis, tend to result in only mild erosive disease. Early bony erosions occur at the cartilaginous edge, and cartilage is initially preserved, with maintenance of a normal joint space.

X-ray findings that are characteristic of psoriatic arthritis include:

- Changes affecting the joints at the end of the fingers and toes

- Asymmetrical joint involvement particularly of the sacroiliac joints

- Erosions: Destruction of the bone and cartilage adjacent to joint spaces

- “Pencil-in-cup” deformity: results from periarticular erosions and bone resorption giving the appearance of a pencil in a cup.

- Subluxation: slipping of the alignment of the joint

- Ankylosis: fusion of bones together across the joint space

- Wispy and dense bony outgrowths around joints (‘whiskering‘ and ‘spurs‘, respectively)

- Increased calcium salt deposition around the insertion of ligaments and tendons into the bone and other features of enthesopathy.

- Ivory phalanx: increased radiodensity of an entire phalanx as a result of periosteal and endosteal bone formation.

MRI and ultrasound can also aid diagnosis, by identifying enthesitis, tendinitis and ligamentous inflammation.

Classification of psoriatic arthritis

The Classification Criteria for Psoriatic Arthritis 8 consist of established inflammatory articular disease with at least 3 points from the following features:

- Current psoriasis (assigned a score of 2)

- A history of psoriasis (in the absence of current psoriasis; assigned a score of 1)

- A family history of psoriasis (in the absence of current psoriasis and history of psoriasis; assigned a score of 1)

- Dactylitis (assigned a score of 1)

- Juxta-articular new-bone formation (assigned a score of 1)

- Rheumatic Factor negativity (assigned a score of 1)

- Nail dystrophy (assigned a score of 1)

Psoriatic arthritis treatment

No cure exists for psoriatic arthritis, so treatment focuses on controlling inflammation in your affected joints to prevent joint pain and disability. Although no clear correlation exists between joint inflammation and the skin in every patient, the skin and joint aspects of the disease often must be treated simultaneously.

Treating psoriatic arthritis varies depending on the level of pain, swelling and stiffness. Those with very mild arthritis may require treatment only when their joints are painful and may stop therapy when they feel better. Non-steroidal anti-inflammatory drugs (NSAIDs) such as ibuprofen (Motrin or Advil) or naproxen (Aleve) are used as initial treatment.

If the arthritis does not respond, disease-modifying antirheumatic drugs (DMARDs may be prescribed. These include sulfasalazine (Azulfidine), methotrexate (Rheumatrex, Trexall, Otrexup, Rasuvo), cyclosporine (Neoral, Sandimmune, Gengraf), and leflunomide. Sometimes combinations of these drugs may be used together. The anti-malarial drug hydroxychloroquine (Plaquenil) can help, but it usually is avoided as it can cause a flare of psoriasis. Azathioprine (Imuran) may help those with severe forms of psoriatic arthritis.

Other treatments include biologics, typically starting with TNF inhibitors such as adalimumab (Humira), certolizumab pegol (Cimzia), etanercept (Enbrel), golimumab (Simponi), infliximab (Remicade). Other biologics used for psoriatic arthritis include the IL-17 inhibitors secukinumab (Cosentyx) and ixekizumab (Taltz), or other classes as ustekinumab (Stelara) and abatacept (Orencia). Newer oral medications, such as tofacitinib (Xeljanz) have also been shown to be effective.

Non-pharmacological management strategies are also very important; these include physical and occupational therapy, exercise, prescription of orthotics, and education regarding the disease and about joint protection, disease management, and the proper use of medications 4. Patients should receive assistance in weight reduction and management of cardiovascular risk factors and other comorbidities.

In general, a stepwise approach to pharmacological treatment is adopted 4:

- Step one

- If arthritis is mild and limited to a few joints and the skin disease is not severe, the skin is treated with topical therapies or phototherapy and the joint disease is managed with pain relief (non-steroidal anti-inflammatory drugs, heat and ice) and possibly corticosteroid injections into the joint.

- Step two

- Non-biological disease-modifying antirheumatic drugs (DMARDs) improve symptoms of pain and stiffness, but none have been shown to prevent progressive joint damage and all have the potential for serious side effects. The following medications have a beneficial effect on joint disease and psoriasis:

- Methotrexate

- Ciclosporin

- Leflunomide

- Apremilast.

- Systemic steroids may help arthritis but can often cause a flare of psoriasis on reduction in dose or discontinuation.

- Non-biological disease-modifying antirheumatic drugs (DMARDs) improve symptoms of pain and stiffness, but none have been shown to prevent progressive joint damage and all have the potential for serious side effects. The following medications have a beneficial effect on joint disease and psoriasis:

- Step three

- Biological TNF-alpha inhibitors. Biologic response modifiers licensed for use in psoriatic arthritis are:

- Adalimumab

- Etanercept

- Infliximab

- Golimumab.

- Biological TNF-alpha inhibitors. Biologic response modifiers licensed for use in psoriatic arthritis are:

- Step four

- Other agents that are under investigation or are available include:

- Abatacept: (CTLA4-Ig) a selective T-cell co-stimulation modulator

- Tofacitinib: a Janus kinase (JAK1 and 3) inhibitor

- Secukinumab, brodalumab, ixekizumab: anti-IL-17 therapies

- Ustekinumab: a human monoclonal antibody to the shared p40 subunit of IL-13 and IL-23

- Filgotinib: a JAK1 inhibitor

- Guselkumab: an anti-leukin (IL)-23 monoclonal antibody

- Upadacitinib: JAK inhibitor.

- Other agents that are under investigation or are available include:

- Step five

- In some cases, the joint disease may require orthopedic surgery.

European League Against Rheumatism (EULAR) recommendations

Based on evidence from systematic literature reviews and expert opinion, the European League Against Rheumatism (EULAR) developed 10 treatment recommendations, 5 overarching principles, and a research agenda for psoriatic arthritis.

The recommendations are as follows 9:

- Nonsteroidal anti-inflammatory drugs (NSAIDs) can be given to relieve musculoskeletal signs and symptoms

- Treatment with disease-modifying antirheumatic drugs (DMARDs)—eg, methotrexate, sulfasalazine, and leflunomide—should be considered at an early stage for patients with active disease

- If a patient with active psoriatic arthritis also has clinically relevant psoriasis, preference should be given to treatment with methotrexate or other disease-modifying antirheumatic drugs (DMARDs) that are also effective against psoriasis

- Adjunctive treatment with local corticosteroid injections should be considered; cautious use of systemic steroids, if administered at the lowest effective dose, can also be considered

- If active psoriatic arthritis fails to adequately respond to 1 or more synthetic, disease-modifying antirheumatic drugs (DMARDs) (eg, methotrexate), tumor necrosis fdactor (TNF)–inhibitor therapy should be employed

- TNF-inhibitor therapy should also be considered if a patient with active enthesitis and/or dactylitis does not show sufficient response to NSAIDs or local steroid injections

- TNF-inhibitor therapy should be considered if a patient has active, predominantly axial disease that does not respond sufficiently to NSAIDs

- Exceptional use of TNF-inhibitor therapy may be considered if a very active patient is DMARD-treatment naïve

- If a TNF inhibitor produces an inadequate response, consideration should be given to replacing it with another TNF inhibitor

- If adjustments are made in a patient’s therapy, then comorbidities, safety concerns, and other considerations beyond the psoriatic arthritis itself should be factored into the change

British Society of Rheumatology recommendations

The British Society of Rheumatology issued guidelines for the treatment of adult psoriatic arthritis with biologic agents (particularly anti-TNF therapy) 10. The British Society of Rheumatology recommends considering anti-TNF treatment in patients with any of the following 10:

- Active peripheral arthritis refractory to at least 2 conventional disease-modifying antirheumatic drugs (DMARDs)

- Peripheral disease refractory to 1 disease-modifying antirheumatic drug (DMARD) plus the presence of adverse prognostic factors

- Severe persistent oligoarthritis that is affecting well-being and refractory to at least 2 disease-modifying antirheumatic drugs (DMARDs) and intra-articular therapy

- Axial disease

The British Society of Rheumatology recommendations on response assessment include the following 10:

- Use the psoriatic arthritis response criteria as the clinical response criteria for peripheral disease

- Use the psoriasis area severity index score for significant skin psoriasis

Safety recommendations include the following 10:

- Do not start or continue anti-tumor necrosis factor (TNF) therapy in patients with serious active infection; use caution in those at high risk of infection

- Screen all patients for infection with mycobacteria, human immunodeficiency virus (HIV), hepatitis B (HBV), and hepatitis C (HCV) before starting anti-TNF therapy

- Consider prophylactic vaccination for tuberculosis and HBV in high-risk patients before initiating anti-TNF therapy

- In patients with HIV, HBV, or HCV, initiate anti-TNF therapy only in those with well-controlled disease and appropriate monitoring; appropriate antiviral therapy for patients with HBV is also important

- Avoid anti-TNF treatment in patients with a current or previous history of malignancy, unless there is a high likelihood of cure or the malignancy was diagnosed and treated more than 10 years ago

- Regularly screen for skin cancers in patients who are receiving anti-TNF therapy and who have a history of current or previous malignancy

- Discontinue anti-TNF therapy prior to pregnancy; restart anti-TNF treatment following the end of lactation or delivery if the mother is not breastfeeding

- Consider an alternative anti-TNF agent in patients whose condition is refractory to a first anti-TNF agent; assess the treatment response as for the first agent.

Psoriatic arthritis medication

Medical treatment regimens include the use of nonsteroidal anti-inflammatory drugs (NSAIDs) and disease-modifying antirheumatic drugs (DMARDs).

Nonsteroidal anti-inflammatory drugs (NSAIDs)

Initial treatment includes NSAIDs for joint disease and topical therapies for the skin. In many patients, this approach is sufficient to control disease manifestations, although some individuals have a worsening of psoriasis with NSAIDs. In these patients, a drug belonging to a different family of NSAIDs should be used.

For people who have morning stiffness, the optimal time for taking an NSAID may be after the evening meal and again upon awakening. Taking NSAIDs with food can reduce stomach discomfort. Any NSAID can damage the mucous layer and cause ulcers and gastrointestinal bleeding when taken for long periods. Cyclooxygenase (COX)–2 selective inhibitors are associated with a lower prevalence of gastric ulcer formation. Other side effects may include heart problems, and liver and kidney damage.

Over-the-counter NSAIDs include ibuprofen (Advil, Motrin IB, others) and naproxen sodium (Aleve). Stronger NSAIDs are available by prescription.

Indomethacin (Indocin)

Indomethacin is thought to be the most effective NSAID for the treatment of ankylosing spondylitis, although no scientific evidence supports this claim. It is used for relief of mild to moderate pain; it inhibits inflammatory reactions and pain by decreasing the activity of cyclooxygenase (COX), which results in a decrease of prostaglandin synthesis.

Ibuprofen (Ibu-tab 200, Motrin IB, Advil, NeoProfen)

Ibuprofen is used for relief of mild to moderate pain; it inhibits inflammatory reactions and pain by decreasing the activity of cyclooxygenase (COX), which results in a decrease of prostaglandin synthesis.

Naproxen (Naprosyn, Naprelan, Aleve, Anaprox)

Naproxen is used for relief of mild to moderate pain; it inhibits inflammatory reactions and pain by decreasing the activity of COX, which results in a decrease of prostaglandin synthesis.

Diclofenac (Zorvolex, Cambia)

Diclofenac inhibits prostaglandin synthesis by decreasing COX activity, which, in turn, decreases formation of prostaglandin precursors.

Immunosuppressants

Immunosuppressants inhibit key factors in the immune system that are responsible for inflammatory responses. These medications act to tame your immune system, which is out of control in psoriatic arthritis.

Methotrexate (Trexall, Otrexup, Rasuvo)

A randomized, 6-month study by Scarpa et al 11 showed that the early use of methotrexate in patients with early psoriatic arthritis markedly improved tender and swollen joints and/or entheses. However, no significant difference was found after 3 months of treatment with NSAIDs or methotrexate. These results suggest that other therapeutic approaches capable of modifying the early course of the disease should be used 12.

Patients receiving long-term methotrexate therapy with high cumulative doses can be monitored using serial liver function tests (LFTs). Liver biopsy should be considered if LFT values are persistently elevated. Pro-collagen 3 N-terminal peptide (PIIINP) is an alternate test, although Lindsay et al 13 reported that PIIINP frequently showed elevated values despite normal liver biopsy results.

Cyclosporine (Sandimmune, Neoral, Gengraf)

Cyclosporine is a cyclic polypeptide that suppresses some humoral immunity and, to a greater extent, cell-mediated immune reactions.

5-Aminosalicylic Acid Derivatives

5-Aminosalicylic acid derivatives inhibit prostaglandin synthesis and reduce the inflammatory response to tissue injury.

Sulfasalazine (Azulfidine, Azulfidine EN-tabs)

Sulfasalazine has been shown to reduce the inflammatory symptoms of psoriatic arthritis.

Disease-modifying antirheumatic drugs (DMARDs)

Disease-modifying antirheumatic drugs (DMARDs) include the following 14:

- Methotrexate

- Sulfasalazine

- Cyclosporine

- Leflunomide

- Biologic agents, such as the anti-tumor necrosis factor (TNF) medications.

There are several biologic type medications available to treat psoriatic arthritis via infusion or injection.

- The anti-tumor necrosis factor (TNF) Inhibitors such as adalimumab (Humira), etanercept (Enbrel), golimumab (Simponi), certolizumab (Cimzia) and infliximab (Remicade) are also available and can help the arthritis as well as the skin psoriasis.

- Secukinumab (Cosentyx), a new type of biologic injection, was recently approved to treat psoriatic arthritis and also can be helpful in treating psoriasis.

- Ustekinumab (Stelara) is a biologic injection given in your doctor’s office that is effective in treating psoriatic arthritis and psoriasis.

- Abatacept is given to patients who have not responded to one or more Disease-modifying antirheumatic drugs (DMARDs) or other biologic drugs. Abatacept may be used alone or in combination with Disease-modifying antirheumatic drugs (DMARDs).

- For swollen joints, corticosteroid injections can be useful. Surgery can be helpful to repair or replace badly damaged joints.

Anti-tumor necrosis factor (TNF)-alpha inhibitors. Tumor necrosis factor-alpha (TNF-alpha) is an inflammatory substance produced by your body. TNF-alpha inhibitors can help reduce pain, morning stiffness, and tender or swollen joints. Examples include etanercept (Enbrel), infliximab (Remicade), adalimumab (Humira), golimumab (Simponi) and certolizumab (Cimzia). Potential side effects include nausea, diarrhea, hair loss and an increased risk of serious infections.

Newer medications. Some newly developed medications for plaque psoriasis can also reduce the signs and symptoms of psoriatic arthritis. Examples include apremilast (Otezla), ustekinumab (Stelara) and secukinumab (Cosentyx).

In patients with severe skin inflammation, medications such as methotrexate, retinoic-acid derivatives, and psoralen plus ultraviolet (UV) light should be considered. These agents have been shown to work on skin and joint manifestations. Intra-articular injection of entheses or single inflamed joints with corticosteroids may be particularly effective in some patients. Use DMARDs in individuals whose arthritis is persistent.

Disease-modifying antirheumatic drugs (DMARDs) – Anti-tumor necrosis factor (TNF) Inhibitors

The use of biologic response modifiers that target anti-tumor necrosis factor (TNF) and other cytokines represents an advance in the treatment of several diseases involving autoimmune mechanisms. Several such agents have been developed, in the form of either soluble fusion proteins (eg, etanercept) or monoclonal antibodies (eg, infliximab, adalimumab), that have shown considerable efficacy in the treatment of rheumatoid arthritis and other autoimmune diseases 15.

Etanercept (Enbrel)

Etanercept is approved by the US Food and Drug Administration (FDA) for (1) treating adult patients (age ≥18 y) with chronic, moderate to severe plaque psoriasis; (2) reducing the symptoms and signs of moderate to severe polyarticular-course juvenile rheumatoid arthritis and ankylosing spondylitis; and (3) reducing the signs and symptoms and inhibiting the progression of structural damage associated with psoriatic arthritis. Therefore, etanercept may be an effective and safe alternative monotherapy for the treatment of psoriatic arthritis.

Infliximab (Inflectra, Remicade)

Infliximab is another TNF-neutralizing agent. It has been approved for the treatment of Crohn disease, ulcerative colitis, rheumatoid arthritis (in combination with methotrexate), ankylosing spondylitis, and psoriatic arthritis (and has shown success in reducing the signs and symptoms of this disease) 16.

However, the FDA has issued safety warnings for infliximab concerning worsening heart failure in patients with moderate to severe chronic heart failure, as well as risk for opportunistic infections such as tuberculosis, histoplasmosis, listeriosis, and pneumocystosis.

Golimumab (Simponi, Simponi Aria)

Golimumab is an FDA-approved human TNF-alpha antibody that is given every 4 weeks as a subcutaneous injection at doses of 50 mg and 100 mg. It has been shown to significantly improve symptoms of psoriatic arthritis 15.

Ustekinumab (Stelara)

Ustekinumab is an anti-IL-12/23 monoclonal antibody approved for treatment of active psoriatic arthritis in adult patients. It may be administered alone or in combination with methotrexate. It is approved in doses of 45 mg or 90 mg SC given at weeks 0 and 4 and then every 12 weeks. At week 24 of the PSUMMIT 1 trial, 42% of patients receiving 45 mg and 50% of patients receiving 90 mg demonstrated at least a 20% improvement in signs and symptoms as measured by the American College of Rheumatology (ACR 20). These improvements were maintained at week 52 of the study 17.

Certolizumab pegol (Cimzia)

Other new biologic agents in clinical trials include certolizumab pegol, a PEGylated Fab’ fragment of an anti–TNF-alpha monoclonal antibody. Certolizumab pegol has shown promising results in the treatment of rheumatoid arthritis and may be applicable to the treatment of psoriasis and psoriatic arthritis in the future.

Adalimumab (Humira, Amjevita, Adalimumab-atto)

Recombinant human anti-TNF-alpha IgG1 monoclonal antibody. Blocks inflammatory activity of TNF-alpha, by specifically binding to TNF-alpha and blocks its interaction with p55 and p75 cell surface TNF receptors. It is indicated for reduction of signs and symptoms, inhibition of progression of structural damage, and improvement of physical function in adults with active psoriatic arthritis.

Disease-modifying antirheumatic drugs (DMARDs) – PDE4 Inhibitors

Agents which increase intracellular cyclic adenosine monophosphate (cAMP), such as PDE4 inhibitors, may have an antagonistic effect on proinflammatory molecule production.

Apremilast (Otezla)

Apremilast is an oral, small molecule inhibitor of phosphodiesterase-4 specific for cAMP, resulting in increased intracellular cAMP levels. The specific mechanism by which apremilast exerts it therapeutic action in psoriatic arthritis is not well defined. It is indicated for treatment of active psoriatic arthritis. It is indicated for active psoriatic arthritis.

Disease-modifying antirheumatic drugs (DMARDs) – Immunomodulators

Abatacept is a selective costimulation modulator that inhibits T-cell activation.

Abatacept (Orencia, Orencia ClickJect)

Chimeric protein which inhibits T-lymphocyte activation by binding to CD80 and CD86 located on antigen presenting cells (APC). T-cell activation is dependent on interacting with APC. Indicated for active psoriatic arthritis in adults.

Interleukin Inhibitors

Various interleukins play a role in inflammatory processes.

Secukinumab (Cosentyx)

Human IgG1 monoclonal antibody that selectively binds to and neutralizes the proinflammatory cytokine interleukin 17A (IL-17A). IL-17A is a naturally occurring cytokine that is involved in normal inflammatory and immune responses. It is indicated for adults with active psoriatic arthritis.

Physical therapy

The rehabilitation treatment program for patients with psoriatic arthritis should be individualized and should be started early in the disease process. Such a program should consider the use of the following:

- Rest: Local and systemic

- Exercise: Passive, active, stretching, strengthening, and endurance

- Modalities: Heat, cold

- Orthotics: Upper and lower extremities, spinal

- Assistive devices for gait and adaptive devices for self-care tasks: Including possible modifications to homes and automobiles

- Education about the disease, energy conservation techniques, and joint protection

- Possible vocational readjustments

With regard to the first item above, prolonged rest should be avoided to prevent the deleterious effects of immobility. In a very few people, psoriatic arthritis may cause extreme fatigue.

Acute phase

Encourage rest as indicated. Splints may be used for rest and pain relief, especially for the hands, wrists, knees, or ankles. Cold modalities should be used to decrease inflammation and assist with pain relief. Joints should not be moved beyond the limit of pain; passive movements should be limited at this time. Education should be completed during this phase, with topics including the disease itself, the importance of rest, the exercise program, joint protection, energy conservation, and weight loss, if appropriate.

Subacute and long-term phase

Isometric exercises are begun, with progression to active movement. Gradual range-of-motion (ROM) exercises include passive and active exercises; areas with subluxation should not be forced passively. Heating modalities, including moist heat packs, paraffin wax, diathermy, and ultrasound, can be used to decrease pain; heat therapy should be administered just prior to the performance of ROM exercises.

Institute gait activities, with the patient bearing weight as tolerated, with or without an assistive device. Gentle stretching should be gradually introduced. If pain persists beyond 2 hours after therapies, then the intensity should be decreased. If a joint is swollen, then no resistive exercises should be performed through full ROM.

For patients with axial spine involvement, spine extension exercises help with flexibility and strength. ROM exercises should be performed, but not in patients with increased pain.

If the patient has sausage toes, extra-depth shoes with a high toe box should be considered to protect the foot. With pain in the toes, such shoes should have a rocker-bottom modification to alleviate forces during the toe-off phase in the gait cycle. The patient may also benefit from arch supports if plantar fascitis is a problem.

Psoriatic arthritis diet

Currently there is no study or literature on psoriatic arthritis diet. However, there are plenty of research on dietary management for rheumatoid arthritis. Based on findings discussed in Khanna et al review 18, they have designed an anti-inflammatory food chart (see Table 1) that may aid in reducing signs and symptoms of rheumatoid arthritis. This may not cure the patients; however, an effective incorporation of these food items in the daily food plan may help to reduce their disease activity, delay disease progression, and reduce joint damage, and eventually a decreased dose of drugs administered for therapeutic treatment of patients. The believe that an ideal meal can include raw or moderately cooked vegetables (lots of greens, legumes), with addition of spices like turmeric and ginger 19, seasonal fruits 20, probiotic yogurt 21; all of which are good sources of natural antioxidants and deliver anti-inflammatory effects. The patient should avoid any processed food, high salt 22, oils, butter, sugar, and animal products 23. Dietary supplements like vitamin D 24, cod liver oil 25, and multivitamins 26 can also help in managing rheumatoid arthritis. This diet therapy with low impact aerobic exercises can be used for a better degree of self-management of rheumatoid arthritis with minimal financial burden 27. A better patient compliance is, however, always necessary for effective care and management of rheumatoid arthritis.

Table 1. Recommended anti-inflammatory food chart

| Fruits | Dried plums, grapefruits, grapes, blueberries, pomegranate, mango (seasonal fruit), banana, peaches, apples |

| Cereals | Whole oatmeal, whole wheat bread, whole flattened rice |

| Legumes | Black soybean, black gram |

| Whole grains | Wheat, rice, oats, corn, rye, barley, millets, sorghum, canary seed |

| Spices | Ginger, turmeric |

| Herbs | Sallaki, ashwagandha |

| Oils | Olive oil, fish oil, borage seed oil (in encapsulated form) |

| Miscellaneous | Yogurt (curd), green tea, basil (tulsi) tea |

Psoriatic arthritis prognosis

Most people with psoriatic arthritis will have ongoing problems with arthritis throughout the rest of their life. Remissions are uncommon; occurring in less than 20% of patients with less than 10% of patients having a complete remission off all medication with no signs of joint damage on X-rays. People with severe psoriatic arthritis have been reported to have a shorter lifespan than average.

Features associated with a relatively good prognosis are:

- Male sex

- Fewer joints involved

- Good functional status at presentation

- Previous remission in symptoms.

Features associated with a poor prognosis include:

- ESR > 15 mm/hr or raised CRP at presentation

- Failure of previous medication trials

- Absence of nail changes

- Joint damage (clinically or radiographically)

- HLA-B27-, -B39-, or -DQw3-positive status.

Living with psoriatic arthritis

Many people with arthritis develop stiff joints and muscle weakness due to lack of use. Proper exercise is very important to improve overall health and keep joints flexible. This can be quite simple. Walking is an excellent way to get exercise. A walking aid or shoe inserts will help to avoid undue stress on feet, ankles, or knees affected by arthritis. An exercise bike provides another good option, as well as yoga and stretching exercises to help with relaxation.

Aqua therapy can be beneficial as some people with psoriatic arthritis find it easier to move in water. If this is the case, swimming or walking laps in the pool offers activity without stressing joints. Many people with psoriatic arthritis also benefit from physical and occupational therapy to strengthen muscles, protect joints from further damage, and increase flexibility.

Lifestyle and home remedies for psoriatic arthritis

- Protect your joints. Changing the way you carry out everyday tasks can make a tremendous difference in how you feel. For example, you can avoid straining your finger joints by using gadgets such as jar openers to twist the lids from jars, by lifting heavy pans or other objects with both hands, and by pushing doors open with your whole body instead of just your fingers.

- Maintain a healthy weight. Maintaining a healthy weight places less strain on your joints, leading to reduced pain and increased energy and mobility. The best way to increase nutrients while limiting calories is to eat more plant-based foods — fruits, vegetables and whole grains.

- Exercise regularly. Exercise can help keep your joints flexible and your muscles strong. Types of exercises that are less stressful on joints include biking, swimming and walking.

- Pace yourself. Battling pain and inflammation can leave you feeling exhausted. In addition, some arthritis medications can cause fatigue. The key isn’t to stop being active entirely, but to rest before you become too tired. Divide exercise or work activities into short segments. Find time to relax several times throughout the day.

Coping and support for psoriatic arthritis

Psoriatic arthritis can be particularly discouraging because the emotional pain that psoriasis can cause is compounded by joint pain and, in some cases, disability.

The support of friends and family can make a tremendous difference when you’re facing the physical and psychological challenges of psoriatic arthritis. For some people, support groups can offer the same benefits.

A counselor or therapist can help you devise coping strategies to reduce your stress levels. The chemicals your body releases when you’re under stress can aggravate both psoriasis and psoriatic arthritis.

References- Ritchlin CT, Colbert RA, Gladman DD. Psoriatic Arthritis. N Engl J Med. 2017 Mar 9. 376 (10):957-970.

- Højgaard P, Christensen R, Dreyer L, et al. Pain mechanisms and ultrasonic inflammatory activity as prognostic factors in patients with psoriatic arthritis: protocol for a prospective, exploratory cohort study. BMJ Open 2016; 6: e010650. doi: 10.1136/bmjopen-2015-010650

- Psoriatic Arthritis. https://www.niams.nih.gov/health-topics/psoriatic-arthritis

- Psoriatic arthritis. https://dermnetnz.org/topics/psoriatic-arthritis

- Overview of Psoriatic Arthritis. https://spondylitis.org/about-spondylitis/overview-of-spondyloarthritis/psoriatic-arthritis

- Psoriatic Arthritis. https://www.rheumatology.org/I-Am-A/Patient-Caregiver/Diseases-Conditions/Psoriatic-Arthritis

- Mease PJ, Reich K. Alefacept with methotrexate for treatment of psoriatic arthritis: open-label extension of a randomized, double-blind, placebo-controlled study. J Am Acad Dermatol. 2009 Mar. 60(3):402-11.

- Taylor W, Gladman D, Helliwell P, Marchesoni A, Mease P, Mielants H. Classification criteria for psoriatic arthritis: development of new criteria from a large international study. Arthritis Rheum. 2006 Aug. 54(8):2665-73.

- Gossec L, Smolen JS, Gaujoux-Viala C, Ash Z, Marzo-Ortega H, van der Heijde D, et al. European League Against Rheumatism recommendations for the management of psoriatic arthritis with pharmacological therapies. Ann Rheum Dis. 2012 Jan. 71(1):4-12.

- [Guideline] Coates LC, Tillett W, Chandler D, et al, on behalf of BSR Clinical Affairs Committee & Standards, Audit and Guidelines Working Group and the BHPR. The 2012 BSR and BHPR guideline for the treatment of psoriatic arthritis with biologics. Rheumatology (Oxford). October 2013. 52(10):1754-7.

- Scarpa R, Peluso R, Atteno M, Manguso F, Spano A, Iervolino S, et al. The effectiveness of a traditional therapeutical approach in early psoriatic arthritis: results of a pilot randomised 6-month trial with methotrexate. Clin Rheumatol. 2008 Jul. 27(7):823-6.

- Otezla (apremilast) prescribing information [package insert]. Summit, NJ.: Celgene Corp. 2014.

- Lindsay K, Fraser AD, Layton A, Goodfield M, Gruss H, Gough A. Liver fibrosis in patients with psoriasis and psoriatic arthritis on long-term, high cumulative dose methotrexate therapy. Rheumatology (Oxford). 2009 May. 48(5):569-72.

- Saad AA, Symmons DP, Noyce PR, Ashcroft DM. Risks and benefits of tumor necrosis factor-alpha inhibitors in the management of psoriatic arthritis: systematic review and metaanalysis of randomized controlled trials. J Rheumatol. 2008 May. 35(5):883-90.

- Mease PJ, Gladman DD, Ritchlin CT, Ruderman EM, Steinfeld SD, Choy EH, et al. Adalimumab for the treatment of patients with moderately to severely active psoriatic arthritis: results of a double-blind, randomized, placebo-controlled trial. Arthritis Rheum. 2005 Oct. 52(10):3279-89.

- Schrader P, Mooser G, Peter RU, Puhl W. [Preliminary results in the therapy of psoriatic arthritis with mycophenolate mofetil]. Z Rheumatol. 2002 Oct. 61(5):545-50.

- Mease PJ, Gottlieb AB, van der Heijde D, FitzGerald O, Johnsen A, Nys M, et al. Efficacy and safety of abatacept, a T-cell modulator, in a randomised, double-blind, placebo-controlled, phase III study in psoriatic arthritis. Ann Rheum Dis. 2017 May 4.

- Khanna S, Jaiswal KS, Gupta B. Managing Rheumatoid Arthritis with Dietary Interventions. Frontiers in Nutrition. 2017;4:52. doi:10.3389/fnut.2017.00052. https://www.ncbi.nlm.nih.gov/pmc/articles/PMC5682732/

- Ramadan G, Al-Kahtani MA, El-Sayed WM. Anti-inflammatory and anti-oxidant properties of Curcuma longa (turmeric) versus Zingiber officinale (ginger) rhizomes in rat adjuvant-induced arthritis. Inflammation (2011) 34(4):291–301.10.1007/s10753-010-9278-0. https://www.ncbi.nlm.nih.gov/pubmed/21120596

- Balbir-Gurman A, Fuhrman B, Braun-Moscovici Y, Markovits D, Aviram M. Consumption of pomegranate decreases serum oxidative stress and reduces disease activity in patients with active rheumatoid arthritis: a pilot study. Isr Med Assoc J (2011) 13(8):474–9.

- Shadnoush M, Shaker Hosseini R, Mehrabi Y, Delpisheh A, Alipoor E, Faghfoori Z, et al. Probiotic yogurt affects pro-and anti-inflammatory factors in patients with inflammatory bowel disease. Iran J Pharm Res (2013) 12(4):929–36.

- van der Meer JW, Netea MG. A salty taste to autoimmunity. N Engl J Med (2013) 368(26):2520–1.10.1056/NEJMcibr1303292

- Manzel A, Muller DN, Hafler DA, Erdman SE, Linker RA, Kleinewietfeld M. Role of “Western diet” in inflammatory autoimmune diseases. Curr Allergy Asthma Rep (2014) 14(1):404.10.1007/s11882-013-0404-6

- Cutolo M, Otsa K, Uprus M, Paolino S, Seriolo B. Vitamin D in rheumatoid arthritis. Autoimmun Rev (2007) 7(1):59–64.10.1016/j.autrev.2007.07.001

- Galarraga B, Ho M, Youssef H, Hill A, McMahon H, Hall C, et al. Cod liver oil (n-3 fatty acids) as an non-steroidal anti-inflammatory drug sparing agent in rheumatoid arthritis. Rheumatology (2008) 47(5):665–9.10.1093/rheumatology/ken024

- Martin RH. The role of nutrition and diet in rheumatoid arthritis. Proc Nutr Soc (1998) 57(02):231–4.10.1079/PNS19980036

- Neuberger GB, Aaronson LS, Gajewski B, Embretson SE, Cagle PE, Loudon JK, et al. Predictors of exercise and effects of exercise on symptoms, function, aerobic fitness, and disease outcomes of rheumatoid arthritis. Arthritis Care Res (2007) 57(6):943–52.10.1002/art.22903