Whole Grain

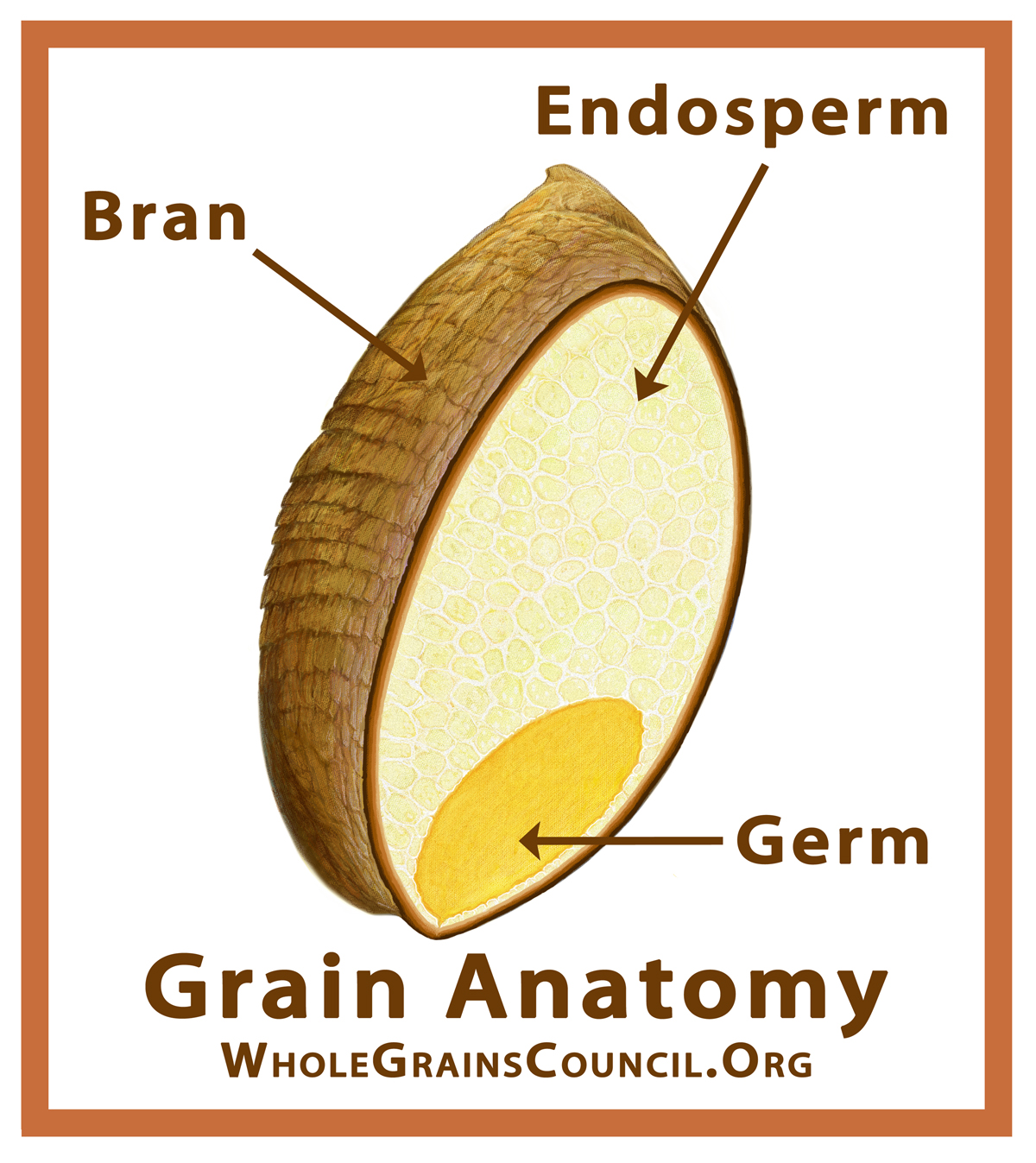

All grains start life as whole grains. In their natural state growing in the fields, whole grains are the entire seed of a plant. A grain is considered to be a whole grain as long as all three original parts — the bran, germ, and endosperm — are still present in the same proportions as when the grain was growing in the fields 1. This seed (also called a “kernel”) is made up of three edible parts – the bran, the germ, and the endosperm – protected by an inedible husk that protects the kernel from assaults by sunlight, pests, water, and disease.

- The term ‘whole grain’ is used to describe an intact grain, flour or a food that contains all three parts of the grain 2.

- “The intact grain or the dehulled, ground, milled, cracked or flaked grain where the constituents – endosperm, germ and bran – are present in such proportions that represent the typical ratio of those fractions occurring in the whole cereal, and includes wholemeal.”

Processing grains does not necessarily produce ‘refined grains’ or exclude them from the definition of a ‘whole grain’.

Examples of foods made with whole grain or wholemeal ingredients include wholemeal and mixed-grain breads, rolls, wraps, flat breads and English muffins, whole grain breakfast cereals, wheat or oat flake breakfast biscuits, whole grain crispbreads, rolled oats, wholemeal pasta, brown rice, popcorn, bulgar (cracked wheat) and rice cakes.

The Bran

The bran is the multi-layered outer skin of the edible grain kernel. Bran is rich in vitamins, minerals, phytonutrients and fibre. It contains important antioxidants, B vitamins and fiber.

The Endosperm

The endosperm is the germ’s food supply, which provides essential energy to the young plant so it can send roots down for water and nutrients, and send sprouts up for sunlight’s photosynthesizing power. The endosperm is by far the largest portion of the kernel. It contains starchy carbohydrates, proteins and small amounts of vitamins and minerals.

The Germ

The germ is the embryo which contains the genetic material for a new plant and has the potential to sprout into a new plant. It contains many B-group vitamins, is abundant in essential healthy fatty acids, some protein, vitamin E, minerals and phytonutrients.

[Source: Grains & Legumes Nutrition Council. Whole Grains 2]Table 1. Grains included in the HEALTHGRAIN whole grain definition

| Cereal | Scientific name |

|---|---|

| Cereals | |

| Wheat, including spelt, emmer, faro, einkorn, khorasan wheat1, durums | Triticum spp. |

| Rice, including brown, black, red, and other coloured rice varieties | Oryza spp. |

| Barley, including hull-less or naked barley but not pearled | Hordeum spp. |

| Maize (corn) | Zea mays |

| Rye | Secale spp. |

| Oats, including hull-less or naked oats | Avena spp. |

| Millets | Brachiaria spp.; Pennisetum spp.; Panicum spp.; Setaria spp.; Paspalum spp.; Eleusine spp.; Echinochloa spp. |

| Sorghum | Sorghum spp. |

| Teff (tef) | Eragrotis spp. |

| Triticale | Triticale |

| Canary seed | Phalaris canariensis* |

| Job’s tears | Coizlacryma-jobi |

| Fonio, black fonio, Asian millet | Digitaria spp. |

| Pseudocereals | |

| Amaranth | Amaranthus caudatus |

| Buckwheat tartar buckwheat | Fagopyrum spp. |

| Quinoa | Chenopodium quinoa Willd. is generally considered to be a single species within the Chenopodioideae |

| Wild rice** | Zizania aquatica |

Footnotes:

1Khorasan wheat – also known as Kamut (registered trademark).

*In the first version of the definition document two scientific names were erroneously mentioned: Phalaris arundinacea and P. canariensis. The former one is a noxious weed.

**In the first version, wild rice was – incorrectly – listed as a cereal and not as a pseudocereal.

Summary

There is a need for a consistent definition of the term “whole grain” and appropriate food standards regarding the proportion of whole grains required in a food in order for it to be classed as a whole grain food, which will together help guide consumer choices. Components in whole grains associated with improved health status include lignans, tocotrienols and phenolic compounds and anti-nutrients such as phytic acid, tannins and enzyme inhibitors. In the grain-refining process the bran is removed, resulting in loss of dietary fibre, vitamins, minerals, lignans, phyto-oestrogens, phenolic compounds and phytic acid 4.

Epidemiological studies find that whole-grain intake is protective against cancer, cardiovascular disease, diabetes and obesity. Potential mechanisms for this protection are diverse since whole grains are rich in nutrients and phytochemicals. First, whole grains are concentrated sources of dietary fibre, resistant starch and oligosaccharides, carbohydrates that escape digestion in the small intestine and are fermented in the gut, producing short-chain fatty acids 4.

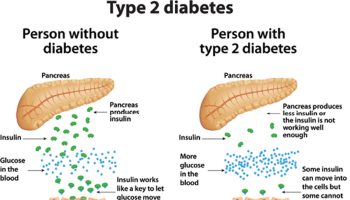

- Whole grain foods are protective against the development type 2 diabetes.

- Whole grain foods and legumes improve indicators of glucose, lipid and lipoprotein metabolism in people with diabetes and in healthy people.

- The acute metabolic advantage in glucose handling appears at least in part to be due to the intact structure of the grain or legume.

- The extent to which the intact structure of grains and legumes contribute to the beneficial effect in terms of prevention and management of diabetes remain to be quantified.

Whole Grain Nutrition

Whole grains contain more than 26 nutrients and phytonutrients, which are bioactive substances thought to play a role in disease protection 2. Whole grains are low in fat and contain protein, dietary fibre (lignans, beta-glucan and soluble pentosans), vitamins (especially B-group vitamins and antioxidant Vitamin E), minerals (iron, zinc, magnesium and selenium) and many bioactive phytochemicals, including:

- Phytosterols – which have cholesterol-lowering properties.

- Sphingolipids – are associated with tumour control and maintenance of normal epithelia.

- Polyphenols and phenolics – such as hydroxycinnamic, ferulic, vanillic and p-coumaric acids, which have antioxidant properties.

- Carotenoids – such as alpha- and beta-carotene, lutein and zeaxanthin), which have antioxidant functions.

- Phytates – which may have a role in lowering glycemic responses and reducing oxidation of cholesterol.

Table 2. 100% Whole Grain – Whole Wheat Flour Nutritional Content

| Nutrient | Unit | cup 30 g | Value per 100 g | |

|---|---|---|---|---|

| Approximates | ||||

| Energy | kcal | 100 | 333 | |

| Protein | g | 4 | 13.33 | |

| Total lipid (fat) | g | 0.5 | 1.67 | |

| Carbohydrate, by difference | g | 20 | 66.67 | |

| Fiber, total dietary | g | 4 | 13.3 | |

| Sugars, total | g | 0 | 0 | |

| Minerals | ||||

| Calcium, Ca | mg | 0 | 0 | |

| Iron, Fe | mg | 1.08 | 3.6 | |

| Sodium, Na | mg | 0 | 0 | |

| Vitamins | ||||

| Vitamin C, total ascorbic acid | mg | 0 | 0 | |

| Thiamin | mg | 0.3 | 1 | |

| Riboflavin | mg | 0.034 | 0.113 | |

| Niacin | mg | 2.666 | 8.887 | |

| Vitamin A, IU | IU | 0 | 0 | |

| Lipids | ||||

| Fatty acids, total saturated | g | 0 | 0 | |

| Fatty acids, total trans | g | 0 | 0 | |

| Cholesterol | mg | 0 | 0 | |

Whole Grains and Disease

As researchers have begun to look more closely at carbohydrates and health, they are learning that the quality of the carbohydrates you eat is at least as important as the quantity. Most studies, including some from several different Harvard teams, show a connection between whole grains and better health 6.

A report from the Iowa Women’s Health Study linked whole grain consumption with fewer deaths from inflammatory and infectious causes, excluding cardiac and cancer causes. Examples are rheumatoid arthritis, gout, asthma, ulcerative colitis, Crohn’s disease, and neurodegenerative diseases. Compared with women who rarely or never ate whole-grain foods, those who had at least two or more servings a day were 30% less likely to have died from an inflammation-related condition over a 17-year period 7.

A meta-analysis combining results from studies conducted in the U.S., the United Kingdom, and Scandinavian countries (which included health information from over 786,000 individuals), found that people who ate 70 grams/day of whole grains—compared with those who ate little or no whole grains—had a 22% lower risk of total mortality, a 23% lower risk of cardiovascular disease mortality, and a 20% lower risk of cancer mortality 8.

Whole Grains and Cardiovascular Disease

Eating whole instead of refined grains substantially lowers total cholesterol, low-density lipoprotein (LDL, or bad) cholesterol, triglycerides, and insulin levels.

In the Harvard-based Nurses’ Health Study, women who ate 2 to 3 servings of whole-grain products each day were 30% less likely to have a heart attack or die from heart disease over a 10-year period than women who ate less than 1 serving per week 9.

A meta-analysis of seven major studies showed that cardiovascular disease (heart attack, stroke, or the need for a procedure to bypass or open a clogged artery) was 21% less likely in people who ate 2.5 or more servings of whole-grain foods a day compared with those who ate less than 2 servings a week 10.

Whole Grains and Type 2 Diabetes

Replacing refined grains with whole grains and eating at least 2 servings of whole grains daily may help to reduce type 2 diabetes risk. The fiber, nutrients, and phytochemicals in whole grains may improve insulin sensitivity and glucose metabolism and slow the absorption of food, preventing blood sugar spikes 11. In contrast, refined grains tend to have a high glycemic index and glycemic load with less fiber and nutrients.

In a study of more than 160,000 women whose health and dietary habits were followed for up to 18 years, those who averaged 2 to 3 servings of whole grains a day were 30% less likely to have developed type 2 diabetes than those who rarely ate whole grains 12. When the researchers combined these results with those of several other large studies, they found that eating an extra 2 servings of whole grains a day decreased the risk of type 2 diabetes by 21%.

A follow-up to that study including men and women from the Nurses’ Health Studies I and II and the Health Professionals Follow-Up Study found that swapping white rice for whole grains could help lower diabetes risk. Those who ate the most white rice—five or more servings a week—had a 17% higher risk of diabetes than those who ate white rice less than one time a month. Those who ate the most brown rice—two or more servings a week—had an 11% lower risk of diabetes than those who rarely ate brown rice. Researchers estimate that swapping whole grains in place of even some white rice could lower diabetes risk by 36% 13.

A large study of more than 72,000 postmenopausal women without diabetes at the start of the study found that the higher the intake of whole grains, the greater the risk reduction of type 2 diabetes. A 43% reduced risk was found in women eating the highest amount of whole grains (2 or more servings daily) as compared with those who ate no whole grains 14.

Whole Grains and Cancer

The data on cancer are mixed, with some studies showing a protective effect of whole grains and others showing none 15, 16.

A large five-year study among nearly 500,000 men and women suggests that eating whole grains, but not dietary fiber, offers modest protection against colorectal cancer 17, 18. A review of four large population studies also showed a protective effect of whole grains from colorectal cancer, with a cumulative risk reduction of 21% 19.

Whole Grains and Digestive Health

By keeping the stool soft and bulky, the fiber in whole grains helps prevent constipation, a common, costly, and aggravating problem. It also helps prevent diverticular disease (diverticulosis) by decreasing pressure in the intestines 20.

A study of 170,776 women followed for more than 26 years looked at the effect of different dietary fibers, including that from whole grains, on Crohn’s disease and ulcerative colitis. Though a reduced risk of Crohn’s disease was found in those eating high intakes of fruit fiber, there was no reduced risk of either disease found from eating whole grains 21.

Some grains contain the naturally-occurring protein, gluten. While gluten can cause side effects in certain individuals, such as those with celiac disease, most people can and have eaten gluten most of their lives—without any adverse reaction. However, negative media attention on wheat and gluten has caused some people to doubt its place in a healthful diet, though there is little published research to support such claims.

For further information on gluten and health, see: What is gluten free diet? and What is celiac disease?

Can eating more whole-grain foods help your blood blood glucose management?

There is no end in sight to the debate as to whether grains help you lose weight or if they promote weight gain. Even more importantly, do whole grains help or hinder blood glucose management ?

a) Swedish researchers at Lund University have determined that certain whole grain products can help control blood sugar for up to ten hours. A team led by Anne Nilsson fed twelve healthy subjects test meals including different whole and refined grains, and found that barley and rye kernels at one meal had a long-lasting effect on controlling blood sugar extending to most of the day after the whole grain breakfast, or overnight with whole grains at dinner 22.

In a more recent study by Janine A. Higgins 23, who studied the subsequent meal effect of whole grain (or second meal effect), which describes the ability of whole grain (and legume) intake at a single meal to influence postprandial glycemia at the next meal. The “second meal effect” describes the glycaemic and/or other physiological responses to a “standard” meal fed several hours after the feeding of a previous meal. It has been shown that consumption of a breakfast having a low GI (glycaemic index) lowers the glycaemic response to a standard lunch taken 4 h later compared with the same lunchtime meal following a higher GI breakfast 24. That is, inclusion of whole grains or legumes at breakfast decreases postprandial glycemia at both lunch and dinner on the same day whereas consumption of a whole grain or lentil dinner reduces glycemia at breakfast the following morning. This effect is apparent whether whole grains and legumes are consumed during breakfast, causing decreased glycemia for the remainder of the day or at dinner, causing lower glycemia at breakfast the following morning. This effect may prove useful for diabetes prevention and could be a factor in the documented relationship between whole grain intake and lower risk of diabetes 23. Additionally, by decreasing glycemia not only following the initial meal but also over the course of the day, the effect of ingesting rapidly absorbed carbohydrates on long-term glycemic control, as measured via HbA1c, may be diminished if whole grains or legumes are also consumed 23. This is a hypothesis that warrants further investigation. It is important to note that extensive milling or cooking negates the subsequent meal effect so whole grains and legumes should be consumed in their native state or with minimal processing for full benefit 23. Finally, it may be concluded that fermentation of indigestible carbohydrate is the primary mechanism whereby whole grains and legumes exert the subsequent meal effect 23.

b) In a study at the University of the Philippines, researchers used a randomized cross-over design to compare the effects on blood glucose of brown rice and white rice on 10 healthy and nine Type 2 diabetic volunteers. In healthy volunteers, the glycemic area and glycemic index were, respectively, 19.8% and 12.1% lower with brown rice than with white rice; with diabetics, the same values for brown rice were 35.2% and 35.6% lower than with white rice. (International Journal of Food Sciences and Nutrition. May-June 2006).

c) At the University of Arkansas, researchers conducted a small randomized crossover trial with 10 healthy men, to compare the impact on blood sugar of eating two different whole grain muffins: a whole sorghum muffin and a whole wheat muffin, each with 50g of total starch. Glucose response averaged 35% lower after the sorghum muffin, leading researchers to suggest that whole grain sorghum could be a good ingredient choice for managing glucose and insulin levels. (Food and Function. March 2014).

d) Dutch researchers used a crossover study with 10 healthy men to compare the effects of cooked barley kernels and refined wheat bread on blood sugar control. The men ate one or the other of these grains at dinner, then were given a high glycemic index breakfast (50g of glucose) the next morning for breakfast. When they had eaten the barley dinner, the men had 30% better insulin sensitivity the next morning after breakfast. (American Journal of Clinical Nutrition, January 2010).

Can eating more whole-grain foods help lower your blood pressure?

It might 25. Eating more whole-grain foods on a regular basis may help reduce your chance of developing high blood pressure (hypertension).

Whole grains are grains that include the entire grain kernel — they haven’t had their bran and germ removed by refining. Whole-grain foods are a rich source of healthy nutrients, including fiber, potassium, magnesium, folate, iron and selenium. Eating more whole-grain foods offers many health benefits that can work together to help reduce your risk of high blood pressure by:

- Aiding in weight control, since whole-grain foods can make you feel full longer

- Increasing your intake of potassium, which is linked to lower blood pressure

- Decreasing your risk of insulin resistance

- Reducing damage to your blood vessels

If you already have high blood pressure, eating more whole-grain foods might help lower your blood pressure and possibly reduce your need for blood pressure medication.

The Dietary Approaches to Stop Hypertension (DASH) diet and the Mediterranean diet both suggest including whole grains as part of a healthy diet.

According to the Dietary Guidelines for Americans 26, as part of an overall healthy diet, adults should eat at least 85 grams of whole-grain foods a day — that’s about 3 ounces, or the equivalent of three slices of whole-wheat bread.

Whole Grain and Health Benefits

Dietary fiber and whole grains contain a unique blend of bioactive components including resistant starches, vitamins, minerals, phytochemicals and antioxidants. As a result, research regarding their potential health benefits has received considerable attention in the last several decades. Epidemiological and clinical studies demonstrate that consumption of dietary fiber and whole grain intake is inversely related to obesity 27, type two diabetes 28, cancer 29 and cardiovascular disease 30.

The American Association of Cereal Chemists 31, define “dietary fiber is the edible parts of plants or analogous carbohydrates that are resistant to digestion and absorption in the human small intestine with complete or partial fermentation in the large intestine. Dietary fiber includes polysaccharides, oligosaccharides, lignin, and associated plants substances. Dietary fibers promote beneficial physiological effects including laxation, and/or blood cholesterol attenuation, and/or blood glucose attenuation” 31. The World Health Organization (WHO) and Food and Agriculture Organization (FAO) agree with the American Association of Cereal Chemists International (AACCI) definition but with a slight variation. They state “Dietary fibre means carbohydrate polymers1 with ten or more monomeric units, which are not hydrolysed by the endogenous enzymes in the small intestine of humans and belong to the following categories: that dietary fiber is a polysaccharide with ten or more monomeric units which is not hydrolyzed by endogenous hormones in the small intestine” 32.

The Food and Drug Administration (FDA) has approved two health claims for dietary fiber. The first claim states that, along with a decreased consumption of fats (<30% of calories), an increased consumption of dietary fiber from fruits, vegetables and whole grains may reduce some types of cancer 33. “Increased consumption” is defined as six or more one ounce equivalents, with three ounces derived from whole grains. A one ounce equivalent would be consistent with one slice of bread, ½ cup oatmeal or rice, or five to seven crackers. The second FDA claim supporting health benefits of dietary fiber states that diets low in saturated fat (<10% of calories) and cholesterol and high in fruits, vegetables and whole grain, have a decreased risk of leading to coronary heart disease 34. For most, an increased consumption of dietary fiber is considered to be approximately 25 to 35 g/d, of which 6 g are soluble fiber.

Recent studies support this inverse relationship between dietary fiber and the development of several types of cancers including colorectal, small intestine, oral, larynx and breast 29, 35, 36. Although most studies agree with these findings, the mechanisms responsible are still unclear. Several modes of actions however have been proposed. First, dietary fiber resists digestion in the small intestine, thereby allowing it to enter the large intestine where it is fermented to produce short chain fatty acids, which have anti-carcinogenic properties 37. Second, since dietary fiber increases fecal bulking and viscosity, there is less contact time between potential carcinogens and mucosal cells. Third, dietary fiber increases the binding between bile acids and carcinogens. Fourth, increased intake of dietary fiber yield increased levels of antioxidants. Fifth, dietary fiber may increase the amount of estrogen excreted in the feces due to an inhibition of estrogen absorption in the intestines 38. Obviously, many studies support the inverse relationship of dietary fiber and the risk for coronary heart disease. However, more recent studies found interesting data illustrating that for every 10 g of additional fiber added to a diet the mortality risk of coronary heart disease decreased by 17–35% 39, 30. Risk factors for CHD include hypercholesterolemia, hypertension, obesity and type two diabetes. It is speculated that the control and treatment of these risk factors underlie the mechanisms behind dietary fiber and coronary heart disease prevention. First, soluble fibers have been shown to increase the rate of bile excretion therefore reducing serum total and LDL “bad” cholesterol 40. Second, short chain fatty acid production, specifically propionate, has been shown to inhibit cholesterol synthesis 41. Third, dietary fiber demonstrates the ability to regulate energy intake thus enhancing weight loss or maintenance of a healthier body weight. Fourth, either through glycemic control or reduced energy intake, dietary fiber has been shown to lower the risk for type two diabetes. Fifth, dietary fiber has been shown to decrease pro-inflammatory cytokines such as interleukin-18 which may have an effect on plaque stability 42. Sixth, increasing dietary fiber intake has been show to decrease circulating levels of C-Reactive protein, a marker of inflammation and a predictor for coronary heart disease 43.

High consumption of whole-grain foods is associated with a reduced risk of chronic diseases including coronary heart disease 44, 45, hypertension (high blood pressure) 46 and type 2 diabetes 47, 48. Suggested mechanisms of action include reduction in serum lipid concentrations 49 and blood pressure 50, increased insulin sensitivity 51 and reduction in thrombotic and inflammatory markers 52, 53.

Whole grains are important dietary components of a healthy lifestyle, and the consumption of whole grains is advocated in the dietary guidelines and nutritional policies of many countries, including the USA (2015) 54, Australia (2013), Canada (2011), Mexico (2006), and various countries in South America, throughout Europe and Asia 55. The 2015-2020 Dietary Guidelines for Americans advised the public to consume at least half of all grains as whole grains, which typically means at least three servings of whole grains daily 54. This recommendation is based on evidence gathered in large part from observational studies on the effects of consumption of whole grains on chronic disease 56. The predominance of evidence from observational and clinical research indicates that the regular consumption of at least three servings of whole grains (16 g/serving) – such as wheat, oats, rice, rye, barley, millet, quinoa and maize – may reduce the risk of developing several chronic diseases. Epidemiological data on whole grains alone are limited compared with data on mixtures of whole grain and bran or foods high in cereal fibre primarily because of varying definitions of what, and how much, was included in that food category 57. The positive association between consumption of oats and reduced risk of cardiovascular disease is represented in a variety of health claims in markets, such as the USA, Canada, Europe and Japan 58. However, the results of the two most comprehensive, well-designed randomised control trials ever conducted with whole-grain foods found no significant effects on the major risk factors for cardiovascular disease 50, 59.

Whole grain intake is associated with a variety of beneficial health effects. In large epidemiological studies, whole grain intake is associated with lower body mass index (BMI) 60 and lower incidence of type 2 diabetes, cardiovascular disease 61, 62 and colorectal cancer 63. Likewise, legume consumption is associated with a reduction in the incidence of type 2 diabetes 64 and, in small prospective intervention studies, with increased glucose tolerance and improved lipemia 65.

One of the mechanisms that may be responsible for the beneficial effects of whole grain and legume consumption is their ability to lower postprandial (after a meal) glucose and insulin responses which, in turn, has effects on hepatic and lipid metabolism 66. The ability of certain whole grains (and legumes) to lower postprandial (after a meal) glycemia is well documented 67, 68. Given the epidemic nature of type 2 diabetes, it is important to emphasise that a diet high in unrefined cereal grain foods and legumes is appropriate for the general population as well as for high-risk families and individuals with diabetes 69.

What is the difference between Whole Wheat and Whole Grain?

Whole wheat is one kind of whole grain, so all whole wheat is whole grain, but not all whole grain is whole wheat.

If you’re reading this in Canada, be aware that Canada has a unique regulatory situation as regards whole wheat flour. Canada allows wheat flour to be called “whole wheat” even when up to 5% of the original kernel is missing. So in Canada you’ll hear two terms used:

- Whole Wheat Flour in Canada — contains at least 95% of the original kernel

- Whole Grain Whole Wheat Flour in Canada — contains 100% of the original kernel

“Whole grain whole wheat flour” would be redundant in the U.S.A. — whole wheat flour is always whole grain in the States. But not in Canada, so be aware.

Finding whole grain foods can be a challenge. Some foods only contain a small amount of whole grain but will say it contains whole grain on the front of the package. For all cereals and grains, read the ingredient list and look for the following sources of whole grains as the first ingredient:

- Bulgur (cracked wheat)

- Whole wheat flour

- Whole oats/oatmeal

- Whole grain corn/corn meal

- Popcorn

- Brown rice

- Whole rye

- Whole grain barley

- Whole farro

- Wild rice

- Buckwheat

- Buckwheat flour

- Triticale

- Millet

- Quinoa

- Sorghum

The structure of all grains is similar and includes the endosperm, germ and bran. The absolute amount of each of these components varies among grains. For example, the bran content of maize is 6 % while that of wheat is 16 %. Important grains in the US diet include wheat, rice, maize and oats 4.

Most rolls, breads, cereals, and crackers labeled as “made with” or “containing” whole grain do not have whole grain as the first ingredient. Read labels carefully to find the most nutritious grain products.

For cereals, pick those with at least 3 grams of fiber per serving and less than 6 grams of sugar.

What’s a Refined Grain and an Enriched Grain?

“Refined grain” is the term used to refer to grains that are not whole, because they are missing one or more of their three key parts (bran, germ, or endosperm). White flour and white rice are refined grains, for instance, because both have had their bran and germ removed, leaving only the endosperm. Refining a grain removes about a quarter of the protein in a grain, and half to two thirds or more of a score of nutrients, leaving the grain a mere shadow of its original self.

Since the late 1800s, when new milling technology allowed the bran and germ to be easily and cheaply separated from the endosperm, most of the grains around the world have been eaten as refined grains. This quickly led to disastrous and widespread nutrition problems, like the deficiency diseases pelagra and beri-beri.

In response, many governments recommended or required that refined grains be “enriched.” Enrichment adds back fewer than a half dozen of the many missing nutrients, and does so in proportions different than they originally existed. The better solution is simply to eat whole grains, now that we more fully understand their huge health advantages.

The chart below compares whole wheat flour to refined wheat flour and enriched wheat flour. You can see the vast difference in essential nutrients.

Chart 1. Vitamins content of Whole Wheat

The grains below, when consumed in a form including the bran, germ and endosperm, are examples of generally accepted whole grain foods and flours.

Amaranth (Amaranthus cruentus)

Amaranth is the common name for more than 60 different species of amaranthus, which are usually very tall plants with broad green leaves and impressively bright purple, red, or gold flowers. Three species — Amaranthus cruenus, Amaranthus hypochondriacus, and Amaranthus caudatus — are commonly grown for their edible seeds.

Amaranth contains more than three times the average amount of calcium and is also high in iron, magnesium, phosphorus, and potassium. It’s also the only grain documented to contain Vitamin C. Very little research has been conducted on amaranth’s beneficial properties, but the studies that have focused on amaranth’s role in a healthy diet have revealed three very important reasons to add it to your diet.

It’s a protein powerhouse. At about 13-14%, it easily trumps the protein content of most other grains. You may hear the protein in amaranth referred to as “complete” because it contains lysine, an amino acid missing or negligible in many grains.

It’s good for your heart. Amaranth has shown potential as a cholesterol-lowing whole grain in several studies conducted over the past 14 years. Qureshi with co-authors 70 showed that feeding of chickens with amaranth oil decreases blood cholesterol levels, which are supported by the work of others 71. The results of the present study on the effect of amaranth oil was studied in a randomized placebo-controlled clinical trial of 125 patients with cardiovascular disease. The patients were randomized to amaranth oil (3 ml amaranth oil provides a 100 mg squalene) 3–18 ml amaranth oil daily. All 125 patients got similar dietary and behavioral recommendations and low-salt diet. Biochemical and clinical indices was monitored during the treatment and after 3 weeks. The experiment was conducted on men and women, aged 32–68, suffering from coronary heart disease and hypertension accompanied by obesity 72. The study shows that amaranth oil can reduce the amount of cholesterol in blood serum and it can be recommended as a functional food product for the prevention and treatment of cardiovascular diseases. Diet with amaranth oil may help reduce blood pressure and could serve as an effective alternative to drug therapy in people with hypertension. This investigation also showed that a combination of amaranth oil with a low salt antiatherogenic diet is more effective to reduce the amount of blood cholesterol than just the low salt antiatherogenic diet alone 72. The next step is to study mechanism of cholesterol lowering properties of amaranth oil.

Last but not least, it’s naturally gluten-free.

Barley (Hordeum vulgare)

Barley is highest in fiber of all the whole grains, with common varieties clocking in at about 17% fiber. For comparison, brown rice contains 3.5% fiber, corn about 7%, oats 10% and wheat about 12%. While the fiber in most grains is concentrated largely in the outer bran layer, barley’s fiber is found throughout the whole grain, which may account for its extraordinarily high levels.

Barley offers many of the same healthy vitamins and minerals as other whole grains, but many think its special health benefits stem from the high levels of soluble beta-glucan fiber found in this grain.

According to a recent review in the journal Minerva Med 73, beta-glucans reduce cholesterol, help control blood sugar, and improve immune system function. New research even indicates that beta-glucans may be radioprotective: they may help our bodies stand up better to chemotherapy, radiation therapy and nuclear emergencies.

Barley Controls Blood Sugar Better: Dutch researchers used a crossover study with 10 healthy men to compare the effects of cooked barley kernels and refined wheat bread on blood sugar control. The men ate one or the other of these grains at dinner, then were given a high glycemic index breakfast (50g of glucose) the next morning for breakfast. When they had eaten the barley dinner, the men had 30% better insulin sensitivity the next morning after breakfast 74.

Barley Lowers Glucose Levels: White rice, the staple food in Japan, is a high glycemic index food. Researchers at the University of Tokushima found that glucose levels were lower after meals when subjects switched from rice to barley 75.

Barley Beta-Glucan Lowers Glycemic Index: Scientists at the Functional Food Centre at Oxfod Brookes University in England fed 8 healthy human subjects chapatis (unleavened Indian flatbreads) made with either 0g, 2g, 4g, 6g or 8g of barley beta-glucan fiber. They found that all amounts of barley beta-glucan lowered the glycemic index of the breads, with 4g or more making a significant difference 76.

Insulin Response better with Barley Beta-Glucan: In a crossover study involving 17 obese women at increased risk for insulin resistance, USDA scientists studied the effects of 5 different breakfast cereal test meals on subjects’ insulin response. They found that consumption of 10g of barley beta-glucan significantly reduced insulin response 77.

Barley Beats Oats in Glucose Response Study: USDA researchers fed barley flakes, barley flour, rolled oats, oat flour, and glucose to 10 overweight middle-aged women, then studied their bodies’ responses. They found that peak glucose and insulin levels after barley were significantly lower than those after glucose or oats. Particle size did not appear to be a factor, as both flour and flakes had similar effects 78.

Barley Reduces Blood Pressure: For five weeks, adults with mildly high cholesterol were fed diets supplemented with one of three whole grain choices: whole wheat/brown rice, barley, or whole wheat/brown rice/barley. All three whole grain combinations reduced blood pressure, leading USDA researchers to conclude that “in a healthful diet, increasing whole grain foods, whether high in soluble or insoluble fiber, can reduce blood pressure and may help to control weight.”79

Barley Lowers Serum Lipids: University of Connecticut researchers reviewed 8 studies evaluating the lipid-reducing effects of barley. They found that eating barley significantly lowered total cholesterol, LDL (“bad”) cholesterol, and triglycerides, but did not appear to significantly alter HDL (“good”) cholesterol 80.

Cholesterol and Visceral Fat Decrease with Barley: A randomized double-blind study in Japan followed 44 men with high cholesterol for twelve weeks, as the men ate either a standard white-rice diet or one with a mixture of rice and high-beta-glucan pearl barley. Barley intake significantly reduced serum cholesterol and visceral fat, both accepted markers of cardiovascular risk 81.

Barley Significantly Improves Lipids: 25 adults with mildly high cholesterol were fed whole grain foods containing 0g, 3g or 6g of barley beta-glucan per day for five weeks, with blood samples taken twice weekly. Total cholesterol and LDL (“bad”) cholesterol significantly decreased with the addition of barley to the diet 82.

Barley Pasta Lowers Cholesterol: University of California researchers fed two test meals to 11 healthy men, both containing beta-glucan. One meal was a high-fiber (15.7g) barley pasta and the other was lower-fiber (5.0g) wheat pasta. The barley pasta blunted insulin response, and four hours after the meal, barley-eaters had significantly lower cholesterol concentration than wheat-eaters 83.

Barley’s Slow Digestion may help Weight Control: Barley varieties such as Prowashonupana that are especially high in beta-glucan fiber may digest more slowly than standard barley varieties. Researchers at USDA and the Texas Children’s Hospital compared the two and concluded that Prowashonupana may indeed be especially appropriate for obese and diabetic patients 84.

Greater Satiety, Fewer Calories Eaten with Barley: In a pilot study 85 not yet published, six healthy subjects ate a 420-calorie breakfast bar after an overnight fast, then at lunch were offered an all-you-can-eat buffet. When subjects ate a Prowashonupana barley bar at breakfast they subsequently ate 100 calories less at lunch than when they ate a traditional granola bar for breakfast 85.

Buckwheat (Fagopyrum esculentum)

Buckwheat contains higher levels of zinc, copper, and manganese than other cereal grains, and the bioavailability of zinc, copper, and potassium from buckwheat is also quite high. Potassium helps to maintain the water and acid balance in blood and tissue cells. Buckwheat also provides a very high level of protein, second highest only to oats. Not only is buckwheat protein well-balanced and rich in lysine, its amino acid score is 100, which is one of the highest amino acid scores among plant sources as well. It’s important to note there is some evidence that the protein digestibility in humans can be somewhat low. While this makes it a less than ideal source of protein for growing children or anyone with digestive tract issues, it’s perfectly fine for the grown-ups of the world 86.

It’s high in soluble fiber 86, helping to slow down the rate of glucose absorption. This can be especially important in people with diabetes and anyone else trying to maintain balanced blood sugar levels. One Slovenian study in 2001 showed boiled buckwheat groats or bread made with at least 50% buckwheat flour induce much lower postprandial (after-meal) blood glucose and insulin responses than white wheat bread.

It’s a potential source of resistant starch 86, a type of starch that escapes digestion in the small intestine. Resistant starch is often considered the third type of dietary fiber because it possesses some of the benefits of insoluble fiber and some of the benefits of soluble fiber. While most of the starch in buckwheat is readily digestible, the small portion that is resistant (about 4-7%) can be highly advantageous to overall colon health.

Buckwheat Enhanced Gluten-free Bread a Healthier Gluten-free Alternative: Researches from the Polish Academy of Sciences recently published a study suggesting substituting some or all of the corn starch in many traditional gluten-free bread recipes with buckwheat flour. In addition to providing higher levels of antioxidants, B vitamins, magnesium, phosphorus and potassium, the study indicated that swapping 40% of the corn starch for buckwheat flour also increased its “overall sensory quality” when compared to the gluten-free bread used in the control. Although recipes were tested with anywhere from 10-40% buckwheat flour, the conclusion clearly points to the 40% buckwheat flour results as having the most nutritional benefits for Celiac sufferers 87.

Buckwheat Starch is A Good Energy Source: In a study found via the China National Knowledge Infrastructure (CNKI), researchers at the Graduate University of the Chinese Academy of Sciences explored the digestibility of starch derived from oats, wheat, buckwheat, and sweet potatoes. The goal of this study was to determine which of the four starch sources might prove useful in high-energy diets. Pigs were fed diets containing vitamins, minerals, and starch from one of the four sources, and after 15 days, it was determined that buckwheat, along with oats and wheat, provided a better source of dietary energy than sweet potatoes 88.

Buckwheat Protein Shows Promise For Lowering Blood Glucose: A study from the Jilin Agricultural University in China investigated the blood glucose lowering potential of buckwheat protein, pitting it against a toxic glucose analogue called alloxan. This insidious chemical selectively destroys insulin-producing cells in the pancreas, causing characteristics similar to type 1 diabetes when found in rodents and many other animal species. Different doses of buckwheat protein were administered, and researchers discovered that the blood glucose levels of test subjects were indeed lowered when compared to the control group 89.

Germinated Buckwheat Extract Decreases Blood Pressure: A team of Korean researchers extracted the bioflavonoid rutin, thought to have blood-pressure lowering properties, from both raw buckwheat (RBE) and germinated buckwheat (GBE). The team then studied the effects of both extracts on body weight and systolic blood pressure in rats. They also searched for any indication of the formation of peroxynitrite, an oxidant and nitrating agent that can damage a wide array of molecules in cells, including DNA and proteins. After five weeks, the systolic blood pressure of the rats treated with GBE was lower than the group treated with RBE, but both groups showed significantly reduced oxidative damage in aortic cells when compared to the control group 90.

Buckwheat Provides Prebiotic-like Benefits And Can Be Considered a Healthy Food: In 2003, a study out of Madrid, Spain examined the high nutrient levels in buckwheat to determine whether it could behave as a prebiotic and be considered a healthy food. Prebiotics, of course, are indigestible food ingredients that stimulate the helpful bacteria in our digestive systems. Not only did the buckwheat-fed group emerge with a lower bodyweight when compared to the control, some of the best types of helpful bacteria were found, along with a decrease in some types of pathogenic bacteria 91.

Eating Buckwheat Products Produces Lower GI Response: It was buckwheat versus itself in a study to determine the characteristics of buckwheat starch and its potential for a reduced metabolic response after meals. In a joint effort, researchers from Slovenia and Sweden scored human test subject’s responses to an assortment of buckwheat products, including boiled buckwheat groats, breads baked with 30-70% buckwheat flour, and bread baked from buckwheat groats. The highest level of resistant starch was found in the boiled buckwheat groats, while the resistant starch levels in the buckwheat breads were significantly lower and depending on whether flour or grouts had been used. The conclusion? All buckwheat products scored significantly lower on the after-meal blood glucose tests, while also scoring higher in satiety, than the control group’s white wheat bread 92.

Bulgur (Triticum ssp.)

When wheat kernels are cleaned, boiled, dried, ground by a mill, then sorted by size, the result is bulgur. This wheat product is sometimes referred to as “Middle Eastern pasta” for its versatility as a base for all sorts of dishes. Because bulgur has been precooked and dried, it needs to be boiled for only about 10 minutes to be ready to eat – about the same time as dry pasta.

Since wheat is by far the most common grain used in breads, pastas and other grain foods eaten in the United States, most U.S. studies of “whole grains” in the aggregate can be considered to attest to the benefits of whole wheat in its common form 93. These benefits are well established, and include, among others:

- stroke risk reduced 30-36%

- type 2 diabetes risk reduced 21-30%

- heart disease risk reduced 25-28%

- better weight maintenance

- reduced risk of asthma

- healthier blood pressure levels

- reduction of inflammatory disease risk

Corn (Zea mays mays)

In the case of corn, its high point is Vitamin A – with more than 10 times that of other grains. Recent research shows that corn is also high in antioxidants and carotenoids that are associated with eye health, such as lutein and zeaxanthin. As a gluten-free grain, corn is a key ingredient in many gluten-free foods 94.

Prebiotic Potential of Whole Maize Cereals: Researchers at the University of Reading, England carried out a double-blind, placebo-controlled human feeding study to explore the potential benefits of eating a whole maize (corn) cereal daily. For 21 days, they offered 32 healthy adults either 48 grams a day of a whole grain corn ceeal or an equal amount of a non-whole-grain cereal placebo, in a cross-over fashion, with a 3-week washout period in between. Fecal bifidobacteria levels increased significantly after 21 days of whole grain cereal, as compared to the refined grain cereal, leading researchers to conclude that whole grain corn can cause a “bifidogenic modulation of the gut microbiota” – an increase in beneficial gut bacteria 95.

Whole Grain Corn High in Resistant Starch Satisfies Longer: An increasing body of research shows that resistant starch, a newly-recognized type of dietary fiber found in grains, cold potatoes, legumes and other foods, has many health benefits. Now researchers at the University of Toronto have found that certain whole grain varieties with naturally-high levels of resistant starch may be especially good at making us feel full longer. In the study, 17 male volunteers consumed five different test soups, at one week intervals, after which scientists recorded their glycemic response and their food intake at various intervals over the next few hours. Eating whole grain corn soup with 66% resistant starch content reduced subsequent food intake by 15% compared to eating a high-glycemic control soup 96.

Antidiabetes and Antihypertension potential of corn: Scientists in São Paulo, Brazil, studied ten traditional foods native to the Peruvean Andes, to measure healthy compounds in the foods that are thought to manage early stages of diabetes and high blood pressure. Purple corn scored highest in free-radical-scavenging antioxidant activity, and also had the highest total phenolic content and highest alpha-glucosidase inhibitory activity. The researchers concluded that these native foods, including purple corn, could be useful in designing health-management programs for diabetes and hypertension 97.

Cornbread ranks high as whole grain source: Children and youth with type 1 diabetes must be especially careful to eat well, but, like other children, have strong likes and dislikes. Researchers at the University of Massachusetts Medical School worked with 128 young people, ages 7 to 17, at a diabetes camp, to gauge acceptability of a range of whole grains and legumes. Whole grain cornbread was the favorite (85% tried it and liked it, with another 11% willing to try it) followed by whole wheat bread (72% tried/liked and 3% more were willing to try). Those living in an urban setting or frequently consuming fast food were less willing to try whole grain foods 98.

Carotenoids abound in Corn food products: Carotenoids are plant pigments that act as antioxidants, and are especially associated with eye health. Scientists at Purdue University studied yellow maize (corn) to better understand the bioavailability of the carotenoids therein. They found that lutein and zeaxanthin were the major carotenoids, making up about 70% of total carotenoid content. They also found that bioavailability of different carotenoids varied according to the type of foods (breads, extruded corn puffs, porridge) 99.

Millet (Panicum miliaceum, Pennisetum Glaucum, Setaria italica, eleusine coracana, digitaria exilis)

Millet is not just one grain but the name given to a group of several small related grains that have been around for thousands of years and are found in many diets around the world. They include pearl millet (Pennisetum glaucum), foxtail millet (Setaria italica), proso millet (Panicum miliaceum), finger millet / ragi (Eleucine coracana), and fonio (Digitaria exilis). Millet is a gluten-free grain that’s high in antioxidant activity, and also especially high in magnesium, a mineral that helps maintain normal muscle and nerve function.

In addition to being cooked in its natural form, millet can be ground and used as flour (as in Indian roti) or prepared as polenta in lieu of corn meal. As a gluten-free whole grain, millet provides yet another great grain option for those in need of alternatives. Easy to prepare, and becoming easier to find, millet has finally made its way to the American table. Millet can be found in white, gray, yellow or red; and the delicate flavor is enhanced by toasting the dry grains before cooking.

For many years, little research was done on the health benefits of millets, but recently they have been “rediscovered” by researchers, who have found millets helpful in controlling diabetes and inflammation.

Foxtail Millet May Help Control Blood Sugar and Cholesterol: Foxtail millet (Setaria italica) is a common food in parts of India. Scientists at Sri Venkateswara University in that country studied its health benefits in diabetic rats, and concluded that the millet produced a “significant fall (70%) in blood glucose” while having no such effect in normal rats. Diabetic rats fed millet also showed significantly lower levels of triglycerides, and total/LDL/VLDLcholesterol, while exhibiting an increase in HDL cholesterol 100.

Sprouting (Malting) Millet Makes Some Minerals More Bioavailable: In India and some other countries, sprouted (malted) grains are commonly used as weaning foods for infants and as easily-digested foods for the elderly and infirm. A study at the Central Food Technological Research Institute in Mysore, India, measured the changes caused by malting finger millet, wheat and barley. They found that malting millet increased the bioaccessibility of iron (> 300%) and manganese (17%), and calcium (“marginally”), while reducing bioaccessibility of zinc and making no difference in copper. The effects of malting on different minerals varied widely by grain 101.

All Millet Varieties Show High Antioxidant Activity: At the Memorial University of Newfoundland in Canada, a team of biochemists analyzed the antioxidant activity and phenolic content of several varieties of millet: kodo, finger, foxtail, proso, pearl, and little millets. Kodo millet showed the highest phenolic content, and proso millet the least. All varieties showed high antioxidant activity, in both soluble and bound fractions 102.

Millet consumption decreases triglycerides and C-reactive protein: Scientists in Seoul, South Korea, fed a high-fat diet to rats for 8 weeks to induce hyperlipidemia, then randomly divided into four diet groups: white rice, sorghum, foxtail millet and proso millet for the next 4 weeks. At the end of the study, triglycerides were significantly lower in the two groups consuming foxtail or proso millet, and levels of C-reactive protein were lowest in the foxtail millet group. The researchers concluded that millet may be useful in preventing cardiovascular disease 103.

Indian Diabetics Turn to Ragi (Finger Millet) and other Millets: Diabetes is rising rapidly in India, as it is in many nations. Researchers at Sri Devaraj Urs Medical College in Tamaka, Kola, India decided to study the prevalence and awareness of diabetes in rural areas, in order to inform health policy. While there was widespread lack of awareness of the longterm effects of diabetes and diabetic care, common perception favored consumption of ragi, millet and whole wheat chapatis instead of rice, sweets and fruit 104.

Finger Millet (Ragi) Tops in Antioxidant Activity Among Common Indian Foods: The National Institute of Nutrition in Hyderabad, India, carried out a study of the total phenolic content and antioxidant activity of various pulses, legumes and cereals, including millets. Finger millet and Rajmah (a type of bean) were highest in antioxidant activity, while finger millet and black gram dhal (a type of lentil) had the highest total phenolic content 105.

Oats (Avena sativa)

Oats have a sweet flavor that makes them a favorite for breakfast cereals. Unique among grains, oats almost never have their bran and germ removed in processing. So if you see oats or oat flour on the label, relax: you’re virtually guaranteed to be getting whole grain 106.

How to be sure you’re getting whole oats: When you see oats or oatmeal or oat groats on an ingredient list, they are almost invariably whole oats.

Scientific studies have concluded that like barley, oats contain a special kind of fiber called beta-glucan found to be especially effective in lowering cholesterol. Recent research reports indicate that oats also have a unique antioxidant, avenanthramides, that helps protect blood vessels from the damaging effects of LDL cholesterol. For more information on oatmeal, see a post on oatmeal (Is oatmeal good for you?).

Quinoa (Chenopodium quinoa)

Quinoa (Chenopodium quinoa, or goosefoot) is in fact not technically a cereal grain at all, but is instead called a “pseudo-cereal” – a name for foods that are cooked and eaten like grains and have a similar nutrient profile. Botanically, quinoa is related to beets, chard and spinach, and in fact the leaves can be eaten as well as the grains 107. Over 120 different varieties of quinoa are known, but the most commonly cultivated and commercialized are white (sometimes known as yellow or ivory) quinoa, red quinoa, and black quinoa. Quinoa flakes and quinoa flour are increasingly available, usually at health food stores. Go here 108 for pictures and descriptions of the different forms of quinoa.

While the existing research on quinoa pales next to well-studied grains like oats or barley, the pace of quinoa research is picking up, and presenting some intriguing preliminary data.

- Quinoa is a more nutritious option for gluten free diets.

- Quinoa may be useful in reducing the risk for diabetes.

- Quinoa helps you feel fuller longer.

It’s not surprising that quinoa supports good health, as it’s one of the only plant foods that’s a complete protein, offering all the essential amino acids in a healthy balance. Not only is the protein complete, but quinoa grains have an usually high ratio of protein to carbohydrate, since the germ makes up about 60% of the grain. For comparison, wheat germ comprises less than 3% of a wheat kernel. Quinoa is also highest of all the whole grains in potassium, which helps control blood pressure.

What’s more, quinoa is gluten free, which makes it extremely useful to the celiac community and to others who may be sensitive to more common grains such as wheat – or even to all grains in the grass family 107.

Quinoa Offers Antioxidants for Gluten-Free Diets: Researchers suggest that adding quinoa or buckwheat to gluten-free products significantly increases their polyphenol content, as compared to typical gluten-free products made with rice, corn, and potato flour. Products made with quinoa or buckwheat contained more antioxidants compared with both wheat products and the control gluten-free products. Also of note: antioxidant activity increased with sprouting, and decreased with breadmaking 109.

Quinoa’s Excellent Nutritional and Functional Properties: Lillian Abugoch James of the University of Chile reported on the composition, chemistry, nutritional and functional properties of quinoa. She cited the pseudocereal’s “remarkable nutritional qualities” including its high protein content (15%), “great amino acid balance,” and “notable Vitamin E content.” Beyond its nutritional profile, Abugoch recommends quinoa to food manufacturers because of its useful functional properties, such as viscosity and freeze stability 110.

More Protein, Minerals, Fiber in Quinoa: Anne Lee and colleagues at Columbia University’s Celiac Disease Center found that the nutritional profile of gluten-free diets was improved by adding oats or quinoa to meals and snacks. Most notable increases were protein (20.6g vs 11g) iron (18.4mg vs 1.4mg, calcium (182mg vs 0mg) and fiber (12.7g vs 5g) 111.

Quinoa Possible Dietary Aid Against Diabetes: Scientists at the Universidade de São Paulo in Brazil studied ten traditional Peruvian grains and legumes for their potential in managing the early stages of Type 2 diabetes. They found that quinoa was especially rich in an antioxidant called quercetin and that quinoa had the highest overall antioxidant activity (86%) of all ten foods studied. Coming in a close second in antioxidant activity was quinoa’s cousin, kañiwa. This in vitro study led the researchers to conclude that quinoa, kañiwa, and other traditional crops from the Peruvian Andes have potential in developing effective dietary strategies for managing type 2 diabetes and associated hypertension 112.

Quinoa, Oats, and Buckwheat: More Satiating. A University of Milan study compared buckwheat, oats, and, quinoa to see if any of them showed promise in helping with appetite control. In three experiments – one for each grain – subjects’ satisfaction and subsequent calorie consumption were compared, after eating the study grain and after eating wheat or rice. All three study grains had a higher Satiating Efficiency Index (SEI) than wheat or rice; white bread was in fact lowest in appetite satisfaction. Unfortunately, even after feeling fuller from eating the study grains, the subjects did not cut their calories at the next meal 113.

Better Lipid Effects from Quinoa: Also at the University of Milan, researchers compared the digestibility of various gluten-free foods in the lab (in vitro) and then with a group of healthy volunteers (in vivo). Their goal was to gauge the effect of the different foods on postprandial glucose and insulin response, as well as to measure triglycerides and free fatty acids after eating. Quinoa stood out in the study, for producing lower free fatty acid levels and triglyceride concentrations than other GF pastas and breads studied 114.

Kañiwa (Chenopodium pallidicaule or Canihua)

Kañiwa (Chenopodium pallidicaule, also in the goosefoot family) is a cousin of quinoa. Unlike quinoa, kañiwa is not coated in bitter saponins that must first be rinsed away 115.

This grain has a high protein content (15 to 19 percent) and, like quinoa and kiwicha, a high proportion of sulphur-containing amino acids. It has the advantage of not containing saponins, which facilitates its use.

The traditional and most frequent method of consumption is in the form of lightly roasted, ground grains which produce a pleasant flour called cañihuaco. This is consumed on its own, in cold or hot drinks, or in porridges. Over 15 different ways of preparing the whole grain and cañihuaco are known (as entrees, soups, stews, desserts and drinks). In the bakery industry good results have been achieved by adding 20 percent of cañihuaco to wheat flour, which gives the product (bread, biscuits) a pleasant characteristic colour and flavour.

Kañiwa flour also has medicinal uses: it counteracts altitude sickness and fights dysentery while the ashes of its stem can be used as a repellent against insect and spider bites 115.

Rice (Oryza sativa)

Rice (Oryza sativa) provides about half the calories for up to half of the world’s population, especially in parts of Asia, South America and the Indies. Worldwide, it’s second in production to corn – but first in its contribution to human food, since corn is used for many other purposes.

After rice is harvested, its inedible hull must be removed, resulting in a whole grain (often brown) rice kernel, ready to eat. If the rice is milled further, the bran and germ are removed, resulting in white rice, with lower levels of nutrients 116.

Rice is often classified by size and texture. There’s long-, medium-, and short-grain rices, with the former quite elongated and the latter nearly round. Some short-grain rices are known as “sticky” rice because of the extra amylopectin (a kind of starch) that they contain; this stickiness makes them easier to manipulate with chopsticks, and perfect for sushi 116. Aromatic rices have a special fragrance and taste. We’re all familiar with the wonderful fragrance of Basmati or Texmati rice; in India Ambemohar rice, with the fragrance of mango blossoms, is a big favorite.

Brown rice has much higher levels of many vitamins and minerals than white rice. Click here to see a comparision of the nutrient levels in brown and white rice. Other colored rices have similarly higher nutrient levels, but aren’t as well studied as brown rice.

Brown rice is an excellent source of manganese. Just one cup of cooked brown rice provides 88% of your daily need for manganese, a mineral that helps us digest fats and get the most from the proteins and carbohydrates we eat. Manganese also may help protect against free radicals. It’s also a good source of selenium.

Studies indicate that whole grain brown rice may:

- cut diabetes risk

- lower cholesterol

- helped maintain a healthy weight

Black/Brown Rice More Effective in Weight Control: At the Department of Food and Nutrition at Hanyang University in Seoul, Korean researchers randomly assigned forty overweight adult women to two groups. For six weeks, one group ate meals containing white rice, while the other consumed otherwise-identical meals with a mix of black and brown rice. While both groups showed significant reductions in weight, BMI and body fat, the whole grain rice group surpassed the white rice group in all three measures. The whole grain group also saw an increase in HDL (good) cholesterol and in antioxidant activity 117.

Brown Rice, for lower blood glucose in Healthy and Diabetic Subjects: Lower post-prandial blood glucose response can be important both for preventing and for controlling diabetes. In a study at the University of the Philippines, researchers used a randomized cross-over design to compare the effects on blood glucose of brown rice and white rice on 10 healthy and nine Type 2 diabetic volunteers. In healthy volunteers, the glycemic area and glycemic index were, respectively, 19.8% and 12.1% lower with brown rice than with white rice; with diabetics, the same values for brown rice were 35.2% and 35.6” lower than with white rice 118.

Phenols in Brown Rice may Inhibit Breast and Colon Cancer: Rice is a staple in Asia, where breast and colon cancer rates are markedly lower than in the Western world. Scientists at the University of Leicester, UK, analyzed the phenolic compounds in brown rice, brown rice bran, and white milled rice (from the same varietal) to look for known cancer-suppressive compounds. They discovered that several such compounds were present in all three samples, but were found in much lower levels in the white rice. They postulated that consuming rice bran or brown rice instead of white rice may be advantageous with respect to cancer prevention 119.

Switch to Brown Rice Reduces Diabetes Risk in Men and Women: Scientists at the Harvard School of Public Health followed 39,765 men and 157,463 women as part of the Health Professionals Follow-up Study and the Nurses’ Health Study I and II. They found that those eating several servings of white rice per week had a higher risk of Type 2 diabetes and that those eating 2 or more servings of brown rice had a lower risk. They estimate that replacing about two servings a week of white rice with the same amount of brown rice would lower diabetes risk 16% 120.

Black Rice Rivals Blueberries as Antioxidant Source: Scientists working with Zhimin Xu at the Louisiana State University Agricultural Center have found that black rice (sometimes called “forbidden rice”) contains health-promoting antioxidants called anthocyanins, at levels similar to those found in blueberries and blackberries 121.

Black Rice Bran Protects Against Inflammation: S.P. Choi and colleagues from Ajou University in Suwon, South Korea tested both black rice bran and brown rice bran for their effectiveness in protecting against skim inflammation. In mouse tests, they found that the black rice bran did suppress dermatitis, but the brown rice bran did not. The scientists suggest that black rice may be a “useful therapeutic agent for the treatment and prevention of diseases associated with chronic inflammation.” 122

Black Rice Bran High in Antioxidants: A team of researchers at Cornell University, including WGC Scientific Advisor Rui Hai Liu, analyzed the phenolic content and antioxidant activity of 12 diverse varieties of black rice, and found that antioxidants were about six times higher in black rice than in common brown/white rice. The black rice bran had higher content of phenolics, flavonoids and anthocyanins 123.

Rye (Secale cereale)

Rye is a rich and versatile source of dietary fiber, especially a type of fiber called arabinoxylan, which is also known for its high antioxidant activity 124. Rye grain also contains phenolic acids, lignans, alkylresorcinos and many other compounds with potential bioactivities. Research indicates that consuming whole grain rye has many benefits including:

- Improved bowel health

- Better blood sugar control, and reduced risk of type 2 diabetes

- Overall weight management, improved satiety (feeling full longer after eating)

Since rye is consumed widely only in a handful of countries, research into its benefits has not been as widespread as that into some other whole grains. Recently, however, Scandinavian researchers have banded together to step up the pace of research into the benefits of rye and of the Nordic diet overall.

Triticale (Triticosecale rimpaui) is a hybrid of wheat [Triticum] and rye [Secale] that is little more than a century old. The main goal in creating triticale was to produce a grain with many of the advantages of wheat for product development with the ability of rye to thrive in adverse conditions 124.

Rye Reduces Body Weight Compared to Wheat: In this study conducted at Lund University in Sweden, mice were fed whole grain diets based on either wheat or rye, for 22 weeks. Body weight, glucose tolerance, and several other parameters were measured during the study. The researchers concluded that whole grain rye “evokes a different metabolic profile compared with whole grain wheat.” Specifically, mice consuming the whole grain rye had reduced body weight, slightly improved insulin sensitivity, and lower total cholesterol 125.

Rye Lowers Insulin Response, Improves Blood Glucose Profile: In the fight against diabetes and obesity, foods that produce a low insulin response and suppress hunger can be extremely useful. Scientists at Lund University in Sweden examined the effects on 12 healthy subjects of breakfasts made from different rye flours (endosperm, whole grain rye, or rye bran) produced with different methods (baking, simulated sour-dough baking, and boiling). This cross-over study showed that the endosperm rye bread and the whole grain rye bread (especially the “sourdough” one with lactic acid) best controlled blood sugar and regulated appetite 126.

Rye Bread Satisfies Longer than Wheat: At the Swedish University of Agricultural Sciences in Uppsala, researchers fed rye bread (with three varying levels of rye bran) and wheat bread to 16 people, then asked them to rate their appetite (hunger, satiety and desire to eat) for 8 hours afterward. [It’s not known if the wheat bread was whole wheat or refined wheat.] All through the morning and into the afternoon, the three rye bread breakfasts all decreased hunger and desire to eat, compared to the wheat bread control, with the rye bread containing the highest level of bran providing the strongest effect on satiety 127.

Rye may Reduce Inflammation in People with Metabolic Syndrome: At the University of Kuopio in Finland, scientists assigned a group of 47 adults with metabolic syndrome to one of two different 12-week diets. The first group ate a diet with oat, wheat bread and potato (high post-meal insulin response) and the second group at a diet with rye bread and pasta (low post-meal insulin response). The researchers found that the rye/pasta group showed less inflammation than the oat/wheat/potato group. Since inflammation may raise the risk of type 2 diabetes, the researchers concluded that choosing cereal foods wisely may be important to reduce diabetes risk, especially in those who already have metabolic syndrome 128.

Rye Down-Regulates Some Risky Genes: For decades it was believed that genes determined destiny: if you’ve inherited genes that predispose you to heart disease, for example, you will develop cardiovascular disease. More recently, we’ve learned that genes have on/off switches: the potential may be there for your heart attack, but your diet and lifestyle may help you keep that switch turned off, by “down-regulating” the gene. Scientists at the University of Kuopio studied gene expression in 47 middle-aged adults who ate either an oat/wheat bread/potato diet or a rye/pasta diet for 12 weeks. They found 71 down-regulated genes with the rye/pasta group, including some involved with impaired insulin signaling, in contrast to 62 up-regulated genes in the oat/wheat/potato group, including genes that related to stress and over-action of the immune system, even in the absence of weight loss 129.

Sorghum / Milo (Sorghum spp.)

Being gluten-free isn’t sorghum’s only bragging right. It’s also a whole grain that provides many other nutritional benefits. Sorghum, which doesn’t have an inedible hull like some other grains, is commonly eaten with all its outer layers, thereby retaining the majority of its nutrients. Sorghum also is grown from traditional hybrid seeds and does not contain traits gained through biotechnology, making it nontransgenic (non-GMO) 130.

In Africa and parts of Asia, sorghum is primarily a human food product, while in the United States it is used mainly for livestock feed and in a growing number of ethanol plants. However, the United States also has seen food usage on the rise, thanks to the gluten-free benefits of sorghum for those with celiac disease.

Some specialty sorghums are high in antioxidants, which are believed to help lower the risk of cancer, diabetes, heart disease and some neurological diseases. In addition, the wax surrounding the sorghum grain contains compounds called policosanols, that may have an impact on human cardiac health. Some researchers, in fact, believe that policosanols have cholesterol-lowering potency comparable to that of statins 131.

Sorghum May Inhibit Cancer Tumor Growth: Compounds in sorghum called 3-Deoxyanthoxyanins (3-DXA) are present in darker-colored sorgums, and to a lesser extent in white sorghum. Scientists at the University of Missouri tested extracts of black, red, and white sorghums and found that all three extracts had strong antiproliferative activity against human colon cancer cells 132.

Sorghum May Protect Against Diabetes and Insulin Resistance: Advanced glycation endproducts (AGEs) are increasingly implicated in the complications of diabetes. A study from the University of Georgia Neutraceutical Research Libraries showed that sorghum brans with a high phenolic content and high anti-oxidant properties inhibit protein glycation, whereas wheat, rice or oat bran, and low-phenolic sorghum bran did not. These results suggest that “certain varieties of sorghum bran may affect critical biological processes that are important in diabetes and insulin resistance.” 133

Sorghum is Safe for People with Celiac Disease: Up to one percent of the U.S. population (and about ½% worldwide) is believed to have Celiac Disease, an autoimmune reaction to gluten proteins found in wheat, barley and rye. While sorghum has long been thought safe for celiacs, no clinical testing had been done until researchers in Italy made a study. First, they conducted laboratory tests; after those tests established the likely safety, they fed celiac patients sorghum-derived food products for five days. The patients experienced no symptoms and the level of disease markers (anti-transglutaminase antibodies) was unchanged at the end of the five-day period 134.

Sorghum May Help Manage Cholesterol: Scientists at the University of Nebraska observed that sorghum is a rich source of phytochemicals, and decided to study sorghum’s potential for managing cholesterol. They fed different levels of sorghum lipids to hamsters for four weeks, and found that the healthy fats in sorghum significantly reduced “bad” (non-HDL) cholesterol. Reductions ranged from 18% in hamsters fed a diet including 0.5% sorghum lipids, to 69% in hamsters fed a diet including 5% sorghum lipids. “Good” (HDL) cholesterol was not affected. Researchers concluded that “grain sorghum contains beneficial components that could be used as food ingredients or dietary supplements to manage cholesterol levels in humans.” 135

Advantages of Sorghum over Maize in South African Diets: Sorghum has been widely consumed as a staple food and in beverages throughout Africa. More recently, corn has replaced sorghum in some areas. Researchers from the University of Witwatersrand Medical School in South Africa believe that “the change of the staple diet of Black South Africans from sorghum to maize (corn) is the cause of the epidemic of squamous carcinoma of the esophagus.” They link the cancers to Fusarium fungi that grow freely on maize but are far less common on sorghum and note that “countries in Africa, in which the staple food is sorghum, have a low incidence of squamous carcinoma of the esophagus.” 136

Antioxidants in Sorghum High Relative to other Grains and to Fruits: Joseph Awika and Lloyd Rooney, at Texas A&M University, conducted an extensive review of scores of studies involving sorghum, and concluded that the phytochemicals in sorghum “have potential to signiciantly impact human health.” In particular, they cited evidence that sorghum may reduce the risk of certain cancers and promote cardiovascular health 137.

Sorghum May Help Treat Human Melanoma: Scientists in Madrid studied the effect of three different components from wine and one from sorghum, to gauge their effects on the growth of human melanoma cells. While results were mixed, they concluded that all four components (phenolic fractions) “have potential as therapeutic agents in the treatments of human melanoma” although the way in which each slowed cancer growth may differ 138.

Teff (Eragrostis tef)

Teff grains are minute – just 1/150 the size of wheat kernels (less than 1mm diameter – similar to a poppy seed)– giving rise to the grain’s name, which comes from teffa, meaning “lost” in Amharic. Teff has been cultivated and used for human consumption in Ethiopia for centuries.

This nutritious and easy-to-grow type of millet is largely unknown outside of Ethiopia, India and Australia. This interest is mainly attributed to teff being gluten

-free and thus a candidate ingredient for food products destined for people with celiac disease 139, 140. The relatively high nutrient content (i.e. minerals) of teff is also likely to be well suited for celiac patients who usually suffer from mineral malabsorption. Today it is getting more attention for its sweet, molasses-like flavor and its versatility; it can be cooked as porridge, added to baked goods, or even made into “teff polenta.”

Teff grows in three colors: red, brown and white.

The existing literature suggests that teff is composed of complex carbohydrates with slowly digestible starch. Teff has a similar protein content to other more common cereals like wheat, but is relatively richer than other cereals in the essential amino acid lysine. Teff is also a good source of essential fatty acids, fiber, minerals (especially calcium and iron), and phytochemicals such as polyphenols and phytates 141 .

Teff leads all the grains – by a wide margin – in its calcium content, with a cup of cooked teff offering 123 mg, about the same amount of calcium as in a half-cup of cooked spinach.

Teff was long believed to be high in iron, but more recent tests have shown that its iron content comes from soil mixed with the grain after it’s been threshed on the ground – the grain itself is not unusually high in iron 142.

Teff is, however, high in resistant starch, a newly-discovered type of dietary fiber that can benefit blood-sugar management, weight control, and colon health. It’s estimated that 20-40% of the carbohydrates in teff are resistant starches. A gluten-free grain with a mild flavor, teff is a healthy and versatile ingredient for many gluten-free products Teff and Millet. https://wholegrainscouncil.org/whole-grains-101/grain-month-calendar/teff-and-millet-%E2%80%93-november-grains-month.

Since teff’s bran and germ make up a large percentage of the tiny grain, and it’s too small to process, teff is always eaten in its whole form. It’s been estimated that Ethiopians get about two-thirds of their dietary protein from teff. Many of Ethiopia’s famed long-distance runners attribute their energy and health to teff.

- Whole Grains Council. Whole Grains 101. https://wholegrainscouncil.org/whole-grains-101

- Grains & Legumes Nutrition Council. Whole Grains. http://www.glnc.org.au/grains-2/grains-and-nutrition/whole-grains/