Thinning hair women

Female pattern hair loss also called androgenic alopecia in women, is a common hair loss in women characterized by diffuse hair thinning over the top (crown) and the sides of head with retention of the frontal hairline due to increased hair shedding or a reduction in hair volume, or both 1, 2. Many women are affected by female pattern hair loss with the prevalence of female pattern hair loss increases with advancing age. Onset of hair loss seems most common at either 20–30 or 40–50 years of age 3, 4. Around 40% of women by age 50 show signs of hair loss and less than 50% of women reach the age of 80 with a full head of hair 5. Female pattern hair loss incidence is highest in Caucasians followed by Asians and African Americans, and the lowest incidence of hair loss is in Native Americans 6. Female-pattern baldness typically starts with scalp hairs becoming progressively finer and shorter as you age. Many women first experience hair thinning and hair loss where they part their hair and on the top-central portion of the head. Some affected women also experience thinning at the frontal hairline or temples. There may be an increase in hair shedding. These changes usually lead to a reduction of the hair volume that may be evident by a shrinking hair ponytail. Some women get episodic bursts of accelerated hair shedding for a few months in between longer stable periods of little activity.

Three different patterns of female pattern hair loss can be observed 7. First is the classic diffuse thinning of the midline scalp, which can be classified using the Ludwig scale (Figure 4). Second, the “Christmas tree pattern” described by Olsen 8, is characterized by frontal midline recession and thinning of the central part of the scalp (Figure 3). Finally, the third pattern presents as hair thinning associated with bitemporal recession, which resembles the classic male pattern hair loss presentation 9. This later pattern is less frequent. The hair pull test is usually negative; however, it may be positive in the frontal scalp as compared with in the occipital scalp due to the shortened hair cycle 7.

Female pattern baldness presents with follicular miniaturization and progressive shortening of the anagen phase, similar to androgenetic alopecia in men (male pattern hair loss) 10; nevertheless, the underlying cause of female pattern hair loss remains unclear 11. The present understanding of relationship between androgenic hormone (androgens are sex hormones that help start puberty and play a role in reproductive health and body development, with male testicles making more androgens than female ovaries) and female pattern hair loss is controversial as evidence suggests normal male sex hormone levels in most balding females, and there is uncertainty regarding its hereditary nature 12.

Female pattern hair loss can affect women in any age group, but it occurs more commonly after menopause. The hair loss process is not constant and usually occurs in fits and bursts. It is not uncommon to have accelerated phases of hair loss for 3–6 months, followed by periods of stability lasting 6–18 months. Without medication, female pattern hair loss tends to progress in severity over the next few decades of life.

Before pursuing hair loss treatment, see your doctor about the cause of your hair loss and what treatment options are available.

The only medicine approved by the United States Food and Drug Administration (FDA) to treat female pattern baldness is minoxidil:

- It is applied to the scalp.

- For women, the 2% solution or 5% foam is recommended. A previous study reported that the effects of minoxidil 5% foam were similar to those of 2% solution twice daily in women 13.

- Minoxidil may help hair grow in about 1 in 4 or 5 of women. In most women, it may slow or stop hair loss.

- You must continue to use this medicine for a long time. Hair loss starts again when you stop using it. Also, the hair that it helps grow will fall out.

If minoxidil does not work, your doctor may recommend other medicines, such as spironolactone, cimetidine, birth control pills, ketoconazole, among others. Your doctor can tell you more about these if needed.

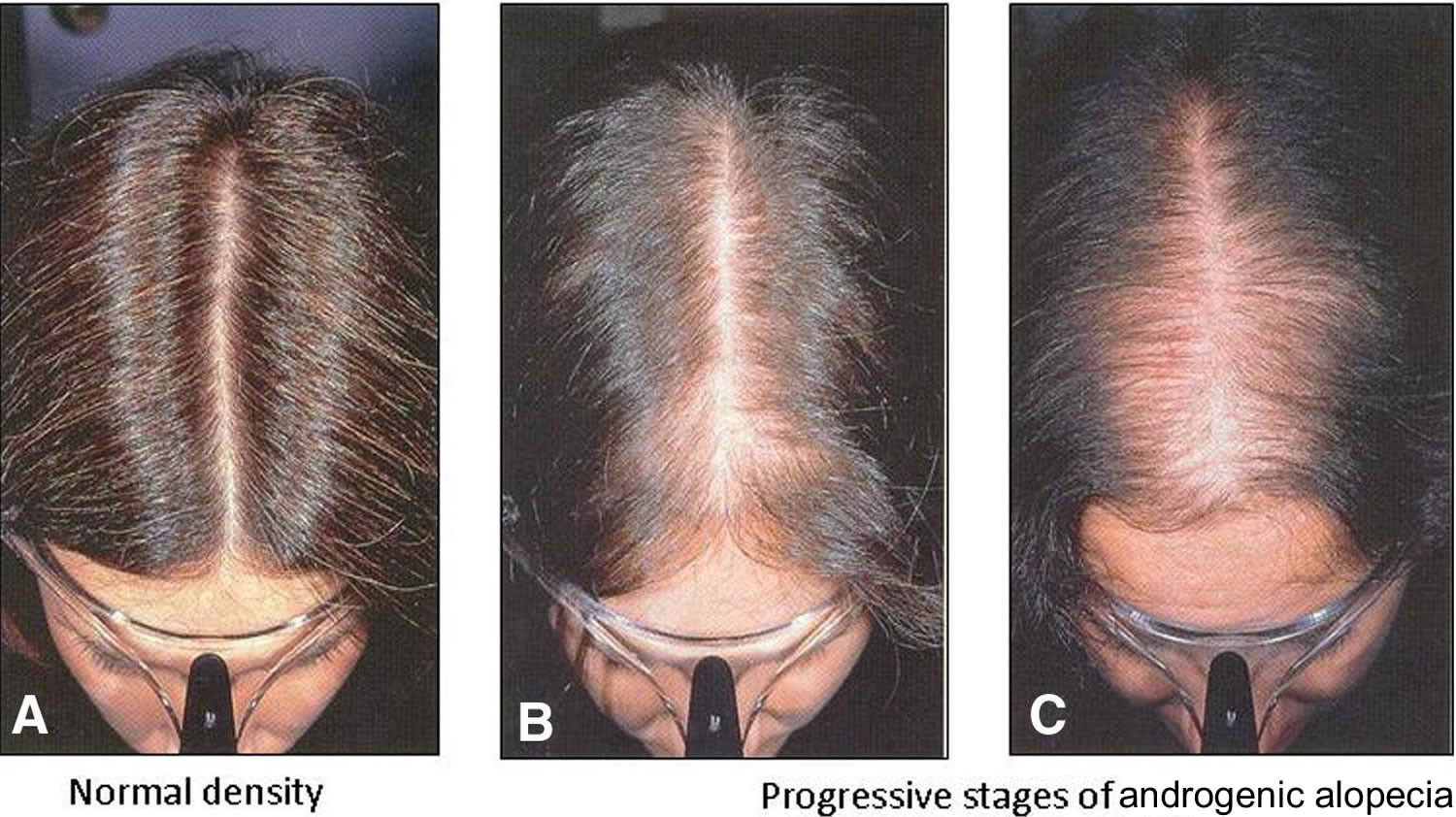

Figure 1. Female pattern baldness (androgenic alopecia in women)

Footnote: Female pattern hair loss (androgenic alopecia in women) showing hair thinning mostly confined to the crown (top of scalp) with retention of frontal hairline.

[Source 14 ]Figure 2. Female pattern hair loss (androgenic alopecia in women)

Figure 3. Androgenetic alopecia female (female pattern baldness)

Footnote: Androgenetic alopecia in women with ‘Christmas Tree Pattern’

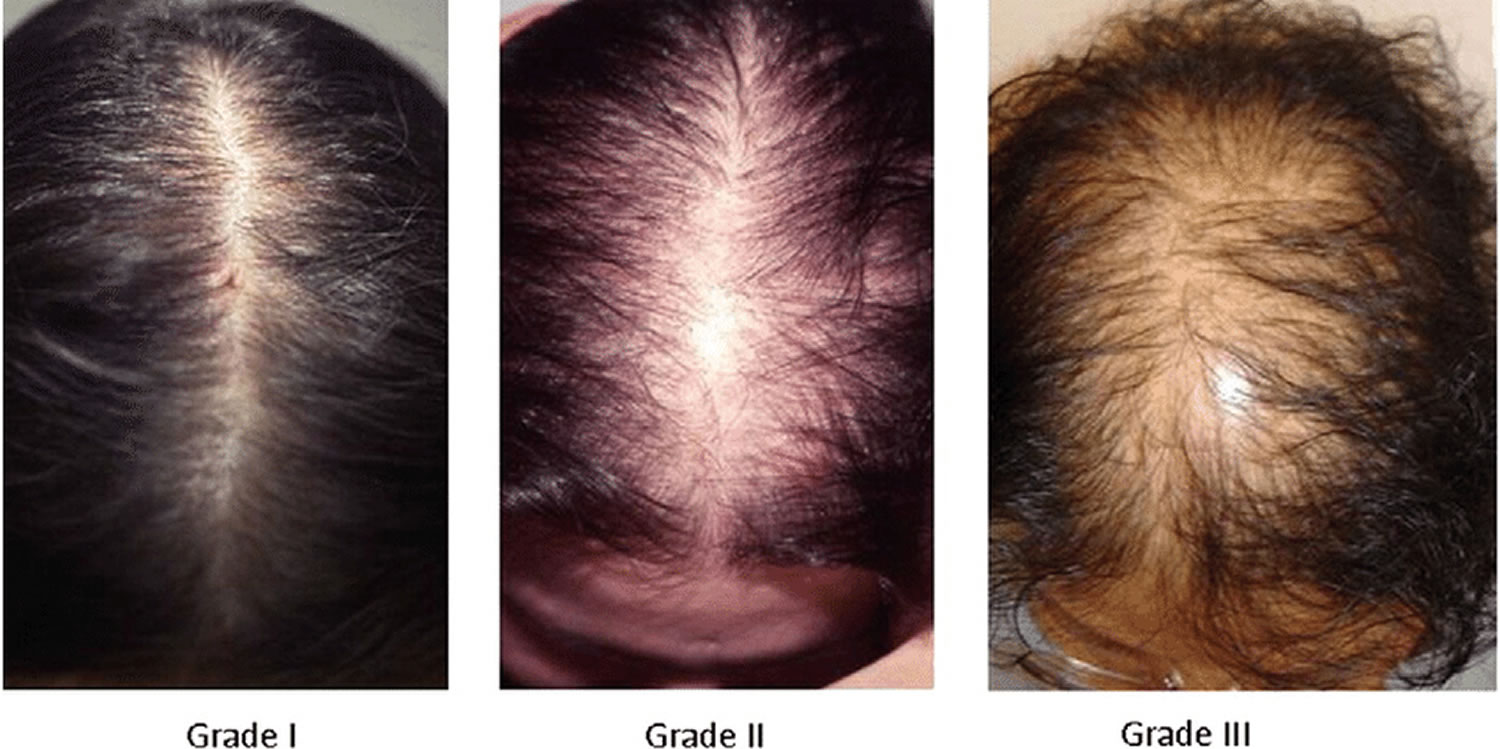

[Source 15 ]Figure 4. Ludwig classification for female pattern hair loss

Footnote: Ludwig classification for female pattern hair loss (androgenic alopecia in women). Grades 1, 2 and 3 (minimal, moderate, intense)

- Grade 1: Perceptible thinning of the hair on the crown, limited in the front by a line situated 1–3 cm behind the frontal hairline.

- Grade 2: Pronounced rarefaction of the hair on the crown, within the area seen in grade 1.

- Grade 3: Full baldness (total denudation) within the area seen in grades 1 and 2.

Figure 5. Male pattern hair loss

You should seek medical advice for hair loss if:

- you have recently started a new medicine;

- you are a woman and your hair loss is accompanied by excess growth of facial and body hair or you have acne;

- you have been diagnosed with (or think you may have) an autoimmune disorder such as systemic lupus erythematosis (SLE), nutritional deficiency or thyroid disease;

- you have been recently treated with chemotherapy or have used a hormonal medicine;

- the hair loss occurs in discrete patches;

- the hair loss is associated with scaling or inflammation of the scalp;

- you also have loss of body hair; or

- you are aware you have a compulsive hair-pulling habit.

How does your hair grow?

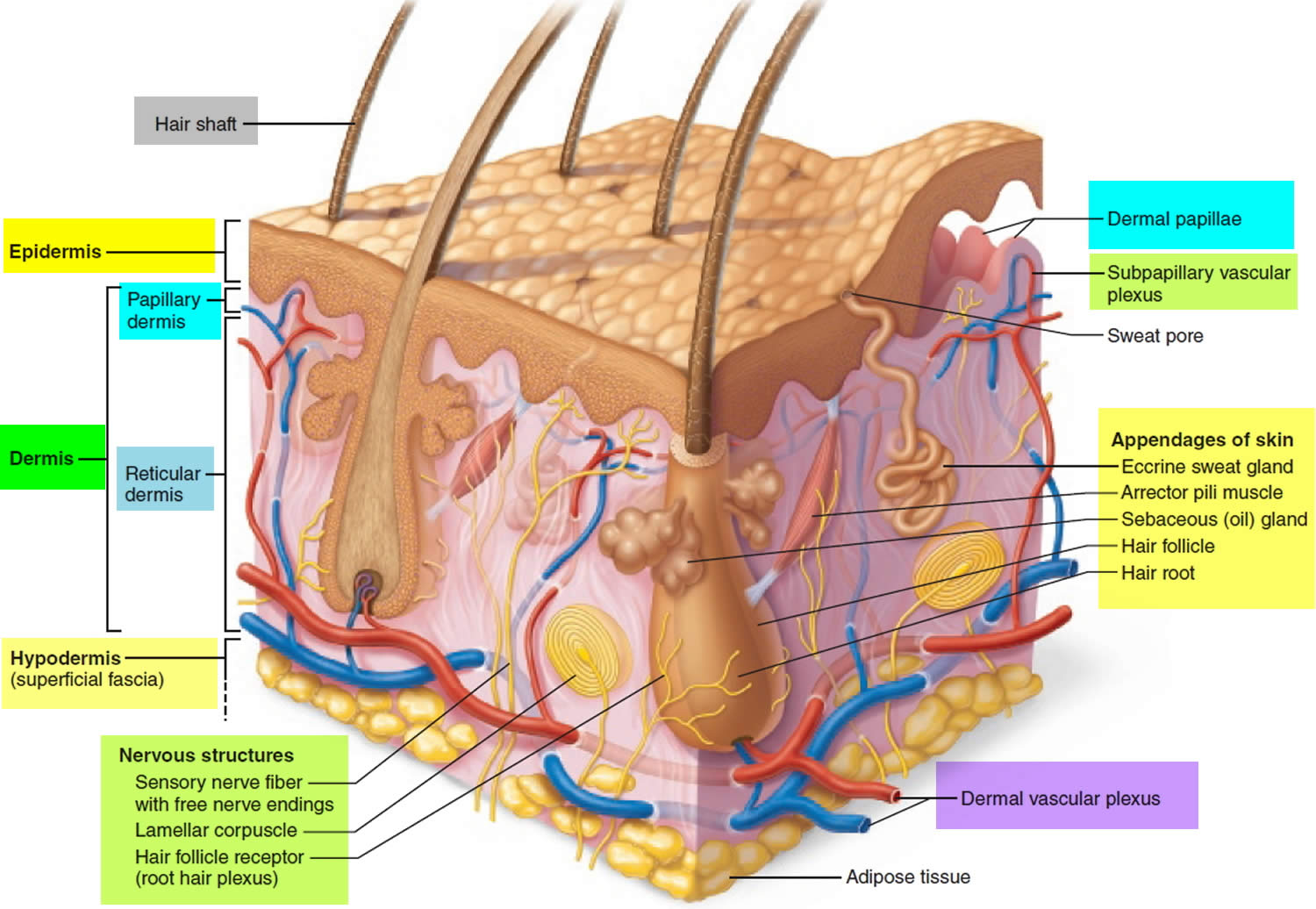

Hair is a slender filament of keratinized cells that grows from an oblique tube in the skin called a hair follicle. Each hair is composed of columns of dead, keratinized epidermal cells bonded together by extracellular proteins. The hair shaft is the superficial portion of the hair, which projects above the surface of the skin. The hair root is the portion of the hair deep to the shaft that penetrates into the dermis, and sometimes into the subcutaneous layer.

Hairs project beyond the surface of the skin almost everywhere except the sides and soles of the feet, the palms of the hands, the sides of the fingers and toes, the lips, and portions of the external genitalia. There are about 5 million hairs on the human body, and 98 percent of them are on the general body surface, not the head. Hairs are nonliving structures that form in organs called hair follicles.

The density of hair does not differ much from one person to another or even between the sexes; indeed, it is virtually the same in humans, chimpanzees, and gorillas. Differences in apparent hairiness are due mainly to differences in texture and pigmentation.

Types of Hairs

Hairs first appear after about three months of embryonic development. These hairs, collectively known as lanugo, are extremely fine and unpigmented. Most lanugo hairs are shed before birth.

The two types of hairs in the adult skin are vellus hairs and terminal hairs:

- Vellus hairs are the fine “peach fuzz” hairs found over much of the body surface.

- Terminal hairs are heavy, more deeply pigmented, and sometimes curly. The hairs on your head, including your eyebrows and eyelashes, are terminal hairs. After puberty, it also forms the armpit and pubic hair, male facial hair, and some of the hair on the trunk and limbs.

Hair follicles may alter the structure of the hairs they produce in response to circulating hormones.

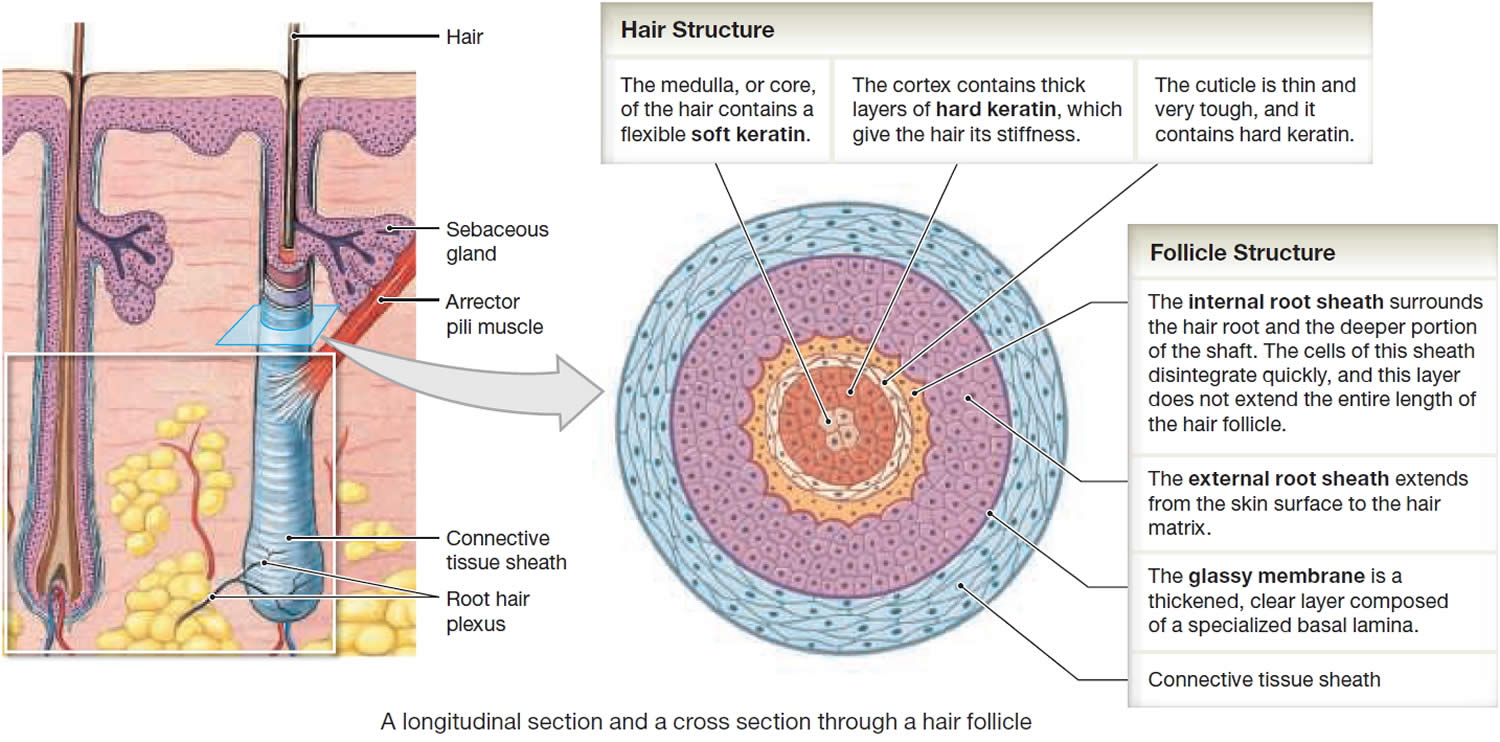

Figure 6. Hair structure

Figure 7. Hair follicle

Structure of Hair Follicle

The portion of a hair above the skin is called the shaft, and all that beneath the surface is the root. The root penetrates deeply into the dermis or hypodermis and ends with a dilation called the hair bulb. The only living cells of a hair are in and near the hair bulb. The hair bulb grows around a bud of vascular connective tissue called the dermal papilla, which provides the hair with its sole source of nutrition. Immediately above the papilla is a region of mitotically active cells, the hair matrix, which is the hair’s growth center. All cells higher up are dead.

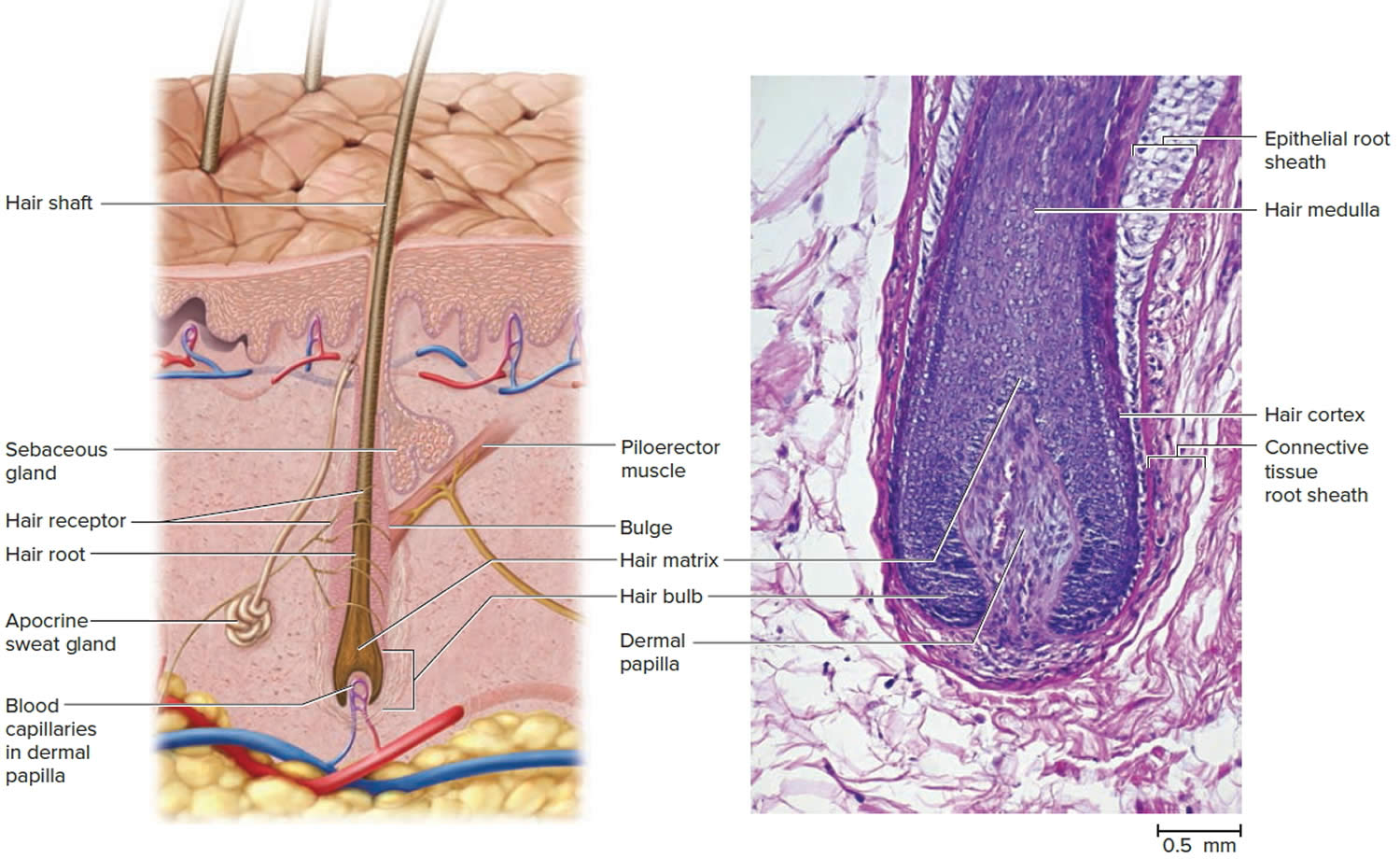

Figure 8. Hair follicle and hair structure

Hair Structure

In cross section, a hair reveals up to three layers. From the inside out, these are the medulla, cortex, and cuticle.

The medulla is a core of loosely arranged cells and air spaces. It is most prominent in thick hairs such as those of the eyebrows, but narrower in hairs of medium thickness and absent from the thinnest hairs of the scalp and elsewhere.

The cortex constitutes most of the bulk of a hair. It consists of several layers of elongated keratinized cells that appear cuboidal to flattened in cross sections.

The cuticle is composed of multiple layers of very thin, scaly cells that overlap each other like roof shingles with their free edges directed upward.

Hair Follicle

Cells lining the hair follicle are like shingles facing in the opposite direction. They interlock with the scales of the hair cuticle and resist pulling on the hair. When a hair is pulled out, this layer of follicle cells comes with it.

The hair follicle is a diagonal tube that contains the hair root. It has two principal layers: an epithelial root sheath and a connective tissue root sheath. The epithelial root sheath is an extension of the epidermis; it consists of stratified squamous epithelium and lies immediately adjacent to the hair root. Toward the deep end of the follicle, it widens to form a bulge, a source of stem cells for follicle growth. The connective tissue root sheath, which is derived from the dermis and composed of collagenous connective tissue, surrounds the epithelial sheath and is somewhat denser than the adjacent dermis.

Associated with the hair follicle are nerve and muscle fibers. Nerve fibers called hair receptors entwine each hair follicle and respond to hair movements. You can feel their effect by carefully moving a single hair with a pin or by lightly running your finger over the hairs of your forearm without touching the skin.

Each hair has a piloerector muscle—also known as a pilomotor muscle or arrector pili—a bundle of smooth muscle cells extending from dermal collagen fibers to the connective tissue root sheath of the follicle. In response to cold, fear, touch, or other stimuli, the sympathetic nervous system stimulates the piloerector to contract, making the hair stand on end and wrinkling the skin in such areas as the scrotum and areola. In humans, it pulls the follicles into a vertical position and causes “goose bumps,” but serves no useful purpose.

Figure 9. Hair structure

Hair Production

Hair follicles extend deep into the dermis, often projecting into the underlying subcutaneous layer. The epithelium at the follicle base surrounds a small hair papilla, a peg of connective tissue containing capillaries and nerves. The hair bulb consists of epithelial cells that surround the papilla.

Hair production involves a specialized keratinization process. The hair matrix is the epithelial layer involved in hair production. When the superficial basal cells divide, they produce daughter cells that are pushed toward the surface as part of the developing hair. Most hairs have an inner medulla and an outer cortex. The medulla contains relatively soft and flexible soft keratin. Matrix cells closer to the edge of the developing hair form the relatively hard cortex. The cortex contains

hard keratin, which gives hair its stiffness. A single layer of dead, keratinized cells at the outer surface of the hair overlap and form the cuticle that coats the hair.

The hair root anchors the hair into the skin. The root begins at the hair bulb and extends distally to the point where the internal organization of the hair is complete, about halfway to the skin surface. The hair shaft extends from this halfway point to the skin surface, where we see the exposed hair tip.

The size, shape, and color of the hair shaft are highly variable.

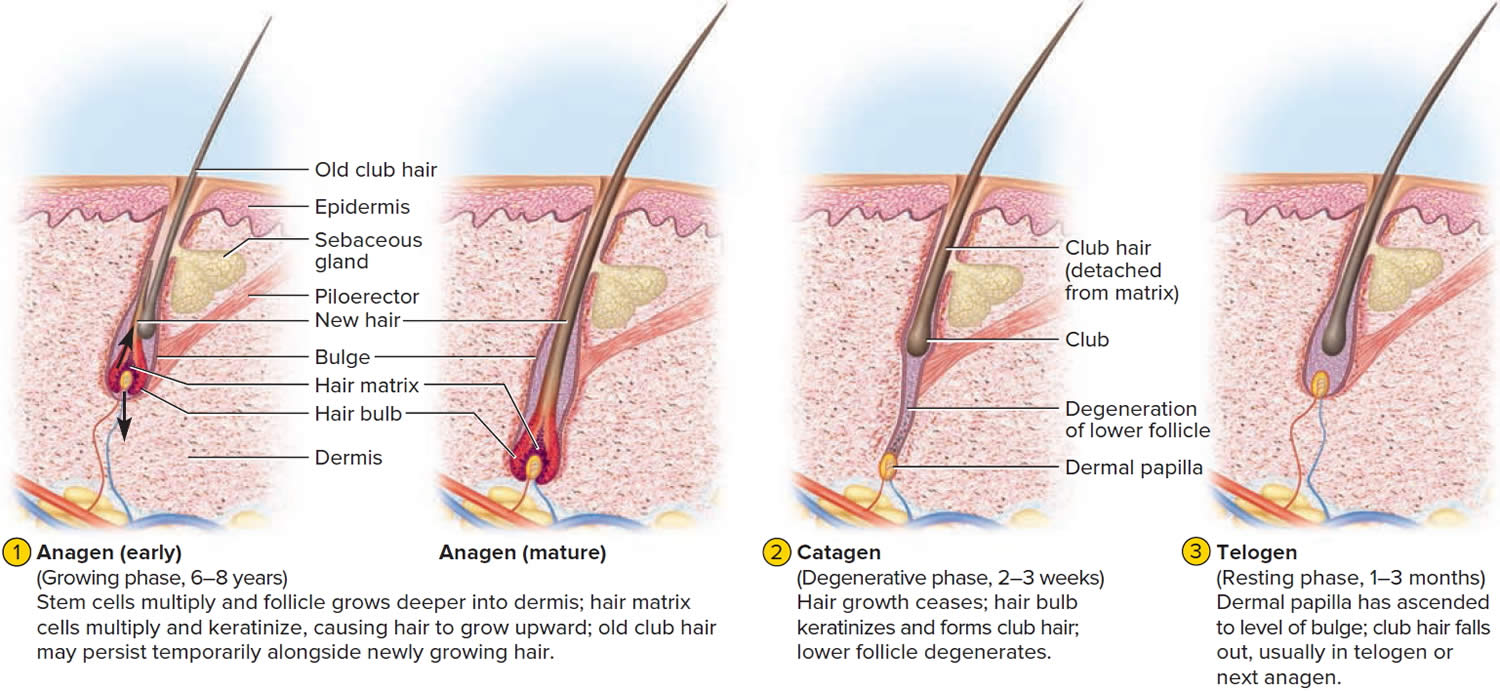

Growth and Replacement of Hair

The human scalp contains about 100,000 hair follicles. These anchor the hair to the skin and contain the cells that produce new hairs. A hair in the scalp grows for two to five years, at a rate of around 0.33 mm/day (about 1/64 inch). Variations in hair growth rate and the duration of the hair growth cycle account for individual differences in uncut hair length. Hair grows in 3 developmental stages:

- Anagen. The anagen phase or actively hair growing phase starts the growing of new hair. The anagen phase is genetically determined and can vary from 2 to 6 years (the average is just under 3 years). Most hair follicles on the scalp are in the anagen phase.

- Catagen. The catagen phase is a transition stage (in-between phase) between the growing and resting phases and lasts 2-3 weeks. The catagen phase is when hair growth stops and the hair follicle shrinks. About 1–3% of hairs are in the catagen phase (in-between phase).

- Telogen. The telogen phase or resting phase is a mature hair with a root, which is held very loosely in the follicle. The telogen phase (resting phase) generally lasts about 4-5 months. Up to 10% of hairs in a normal scalp are in the telogen phase (resting phase). About 100 telogen hairs are lost from the human scalp each day.

Everyone is born with a fixed number of hair follicles on the scalp that produce hairs throughout life. Hair grows from the base of the follicle at a rate of about one centimetre a month for about three years. This growth phase is called anagen. After anagen, the hair dies (catagen hair) and no longer grows. It sits dormant in the follicle for a three-month phase called telogen. After telogen, the hair follicle undergoes another anagen phase to produce new hair that grows out of the same follicle. As it grows, the old telogen hair is dislodged or pushed out. The hair cycle continues throughout life.

At any given time, about 90% of the scalp follicles are in the Anagen stage. In this stage, stem cells from the bulge in the hair follicle multiply and travel downward, pushing the dermal papilla deeper into the skin and forming the epithelial root sheath. Root sheath cells directly above the papilla form the hair matrix. Here, sheath cells transform into hair cells, which synthesize keratin and then die as they are pushed upward away from the papilla. The new hair grows up the follicle, often alongside an old club hair left from the previous cycle.

Hair length depends on the duration of anagen stage. Short hairs (eyelashes, eyebrows, hair on arms and legs) have a short anagen phase of around one month. Anagen lasts up to 6 years or longer in scalp hair.

In the Catagen stage, mitosis in the hair matrix ceases and sheath cells below the bulge die. The follicle shrinks and the dermal papilla draws up toward the bulge. The base of the hair keratinizes into a hard club and the hair, now known as a club hair, loses its anchorage. Club hairs are easily pulled out by brushing the hair, and the hard club can be felt at the hair’s end. When the papilla reaches the bulge, the hair goes into a resting period called the Telogen stage. Eventually, anagen begins anew and the cycle repeats itself. A club hair may fall out during catagen or telogen, or as it is pushed out by the new hair in the next anagen phase.

You lose about 50 to 100 scalp hairs daily. In a young adult, scalp follicles typically spend 6 to 8 years in anagen, 2 to 3 weeks in catagen, and 1 to 3 months in telogen. Scalp hairs grow at a rate of about 1 mm per 3 days (10–18 cm/yr) in the anagen phase.

Hair grows fastest from adolescence until the 40s. After that, an increasing percentage of follicles are in the catagen and telogen phases rather than the growing anagen phase. Hair follicles also shrink and begin producing wispy vellus hairs instead of thicker terminal hairs. Thinning of the hair or baldness, is called alopecia. It occurs to some degree in both sexes and may be worsened by disease, poor nutrition, fever, emotional stress, radiation, or chemotherapy. In the great majority of cases, however, it is simply a matter of aging.

Pattern baldness is the condition in which hair is lost unevenly across the scalp rather than thinning uniformly. It results from a combination of genetic and hormonal influences. The relevant gene has two alleles: one for uniform hair growth and a baldness allele for patchy hair growth. The baldness allele is dominant in males and is expressed only in the presence of the high level of testosterone characteristic of men. In men who are either heterozygous or homozygous for the baldness allele, testosterone causes terminal hair to be replaced by vellus hair, beginning on top of the head and later the sides. In women, the baldness allele is recessive. Homozygous dominant and heterozygous women show normal hair distribution; only homozygous recessive women are at risk of pattern baldness. Even then, they exhibit the trait only if their testosterone levels are abnormally high for a woman (for example, because of a tumor of the adrenal gland, a woman’s principal source of testosterone). Such characteristics in which an allele is dominant in one sex and recessive in the other are called sex-influenced traits.

Excessive or undesirable hairiness in areas that are not usually hairy, especially in women and children, is called hirsutism. It tends to run in families and usually results from either masculinizing ovarian tumors or hypersecretion of testosterone by the adrenal cortex. It is often associated with menopause.

Contrary to popular misconceptions, hair and nails do not continue to grow after a person dies, cutting hair does not make it grow faster or thicker, and emotional stress cannot make the hair turn white overnight.

Different causes of hair loss affect the hair follicles in different phases of growth. See below for the different types of hair loss.

Figure 10. Hair growth cycle

Thinning hair and hair loss in women causes

Genetics usually plays a part in the development of female pattern baldness. The mode of inheritance is polygenic, indicating that there are many genes that contribute to female pattern hair loss, and these genes could be inherited from one or both of your parents. However, some women with female pattern baldness do not have any paternal or maternal family history of baldness. Genetic testing to assess the risk of balding is currently not recommended, as it is unreliable.

Hair loss in females is polygenic and multifactorial with the additional influence of environmental factors 17. Several environmental factors possibly related to female pattern hair loss are psychological stress, high blood pressure (hypertension), diabetes mellitus, smoking, multiple marriages, lack of photoprotection, higher income, and little physical activity 18.

Female pattern baldness is not caused by changes to your diet, infections or hair styling practices.

Currently, it is not clear if androgens (male sex hormones) play a role in female pattern hair loss, although androgens have a clear role in male pattern baldness. The majority of women with female pattern hair loss have normal levels of androgens in their bloodstream 17. The role of enzyme 5 alpha- reductase, which converts testosterone to dihydrotestosterone (DHT) is not clear 19. When testosterone is present in the hair follicle and it combines with the enzyme 5-alpha-reductase type 2, it produces dihydrotestosterone (DHT). Dihydrotestosterone (DHT) is the most potent hormone among the androgens [i.e, dehydroepiandrosterone (DHEA), androstenedione, testosterone, and dihydrotestosterone (DHT)] and is considered a pure androgen as it cannot be converted into estrogen 20. DHT (dihydrotestosterone) attacks the hair follicle, causing it to shrink, finally causing the hair to fall out and not grow back and is implicated in male-pattern hair loss androgenetic alopecia pathophysiology 21. Due to this uncertain relationship, the term female pattern hair loss is preferred to ‘female androgenetic alopecia’. Furthermore, routine hormonal testing is not required but may be recommended by your doctor if you have other signs of androgen excess such as acne, irregular periods, excessive body hair (hirsutism), etc.

In a small number of women with female pattern hair loss have a higher than normal concentration of male hormones in their bodies. These women may lose hair in a similar pattern to men with male pattern hair loss and often have additional symptoms related to this excess of androgens, such as:

- hirsutism (too much hair on the face or body);

- severe acne; or

- irregular periods.

If you have hair loss plus these additional features of androgen excess such as acne, irregular periods, excessive body hair (hirsuitism), your doctor may want to rule out the possibility that a condition such as polycystic ovary syndrome (PCOS) may be causing (or contributing to) your hair loss. Rarely, this combination of symptoms may indicate a tumor that is secreting male hormones.

Female pattern baldness is more common after menopause, suggesting that changes in the levels of female hormones (estrogens) may also be involved. However, the role of estrogen is uncertain. In addition, laboratory experiments have also suggested estrogens may suppress hair growth.

Numerous studies have theorized the effects of estrogen on hair parameters, including anagen phase length. Estrogen has been postulated to have protective effects against hair loss based on differential observations of hair parameters throughout pregnancy, postpartum, and menopause, each characterized by estrogen concentration differences. In pregnancy, characterized by high levels of estrogen, hair growth, and hair diameter increases while the hair shedding decreases 22. These observations have been attributed to estrogen, although other pregnancy-related changes, such as increases in human chorionic gonadotropin (hCG), progesterone, prolactin, growth factors, and cytokines, may additionally contribute 22. In contrast, a decrease in estrogen and progesterone following childbirth is associated with postpartum telogen effluvium. Furthermore, estrogen depletion characteristic of menopause is associated with female pattern hair loss, with decreased hair density and diameter, and decreased anagen phase length 22. The protective role of estrogen in hair loss is further supported by the observation that the frontal hairline of women, often spared in female pattern hair loss, depicts a relatively increased level of aromatase, the enzyme responsible for the conversion of androgens to estrogen 23. However, rather than serum values in isolation, research has suggested that a decreased estrogen to testosterone ratio, rather than absolute values of either hormone, may instead contribute to female pattern hair loss 24. Serum levels of luteinizing hormone (LH), follicle-stimulating hormone (FSH), estradiol, free and total testosterone, sex hormone binding globulin (SHBG) and dehydroepiandrosterone sulfate (DHEAS) were studied among 20 premenopausal women with female pattern hair loss and 9 healthy controls 24. Absolute values of androgens were normal in both groups, although the patients with female pattern hair loss depicted reduced estradiol to free testosterone and estradiol to DHEAS ratios 24. The authors therefore concluded that the estradiol to free testosterone ratio may contribute to female pattern hair loss 24.

Therefore, rather than increasing the absolute values of estrogen, deliberately increasing the estrogen to testosterone ratio may be an effective therapeutic strategy 21. Estrogen replacement therapy has been assessed for the management of hair, both in female and male patients. A case report depicted extensive hair regrowth in a male-to-female transition candidate with androgenic alopecia treated with estradiol supplementation and estrone solution, although simultaneous treatment with minoxidil inhibits the ability to make direct conclusions of the efficacy of estrogen replacement. However, the patient was also treated with anti-androgenic Aldactone (spironolactone), so it is possible extensive hair regrowth occurred due to increased estrogen to testosterone activity 25.

In addition, a study compared the effectiveness of two oral contraceptives, one containing antiandrogenic chlormadinone acetate with synthetic estrogen and another containing synthetic progestin with synthetic estrogen, on acne parameters; the authors also reported resolution rates of hair loss 26. Hair loss resolution rates were 86% and 91% among those receiving chlormadinone/synthetic estrogen and synthetic progestin/synthetic estrogen, respectively 26. This suggests anti-androgenic activity coupled with estrogen replacement, and thus an increased estrogen to testosterone activity ratio may be as effective as an estrogen and progestin replacement for the resolution of hair loss 21. Ultimately, larger, controlled studies are necessary to assess the effectiveness of therapy specifically targeting the estrogen to testosterone ratio. However, prior reports suggest the estrogen to testosterone ratio may be of more value than the absolute values of either hormone, which may further explain why sex hormone concentrations often fail to correlate with reported hair loss symptoms 27.

Thinning hair and hair loss in women pathophysiology

The pathophysiology of female pattern hair loss is complex with genetic, hormonal, and environmental factors playing a key role in it 10. In female pattern hair loss, there is a reduction in the duration of the anagen phase along with the miniaturization of the dermal papilla 28. Miniaturization is the progressive transformation of terminal hair follicles (large, thick, pigmented) to vellus-like hair follicles (short, thin, nonpigmented) and is the hallmark feature in female pattern hair loss 23. These vellus-like hair follicles have a shortened hair cycle because of the reduction in the anagen phase, which leads to the production of fine and short hair shafts. Thus, premature termination of the anagen phase is the key event in the development of female pattern hair loss 17. In addition, there is a delay between the end of the telogen phase and the beginning of the new anagen phase, the so-called kenogen phase, in which the hair follicle remains empty 29.

The diameter of the hair follicle is determined by the size of the dermal papilla and thus miniaturization process is due to a decrease in the volume of the papilla which takes place somewhere between the catagen and the formation of new hair. The factors that lead to miniaturization are not fully known but a possible mechanism is a decrease in the number of papilla cells due to apoptosis 30. The follicular regression in the catagen phase is the outcome of the diffuse apoptosis of follicular keratinocytes 31. Apoptosis occurs as a result of an imbalance between various growth factors and cytokines that promote apoptosis such as fibroblast growth factor 5, interleukin 1 alpha, prostaglandin (PG) D2, transforming growth factor-beta 1, tumor necrosis factor-alpha 1, and those growth factors and cytokines which maintain the anagen phase such as basic fibroblast growth factor, fibroblast growth factor 7, hepatocyte growth factor, insulin-like growth factor 1, PG-E2, vascular endothelial growth factor and Wnt signaling pathway 30.

Thinning hair and hair loss in women prevention

There is no known prevention for thinning hair and hair loss in women. The most common cause of thinning hair and hair loss in women is your genes. The mode of inheritance is polygenic, indicating that there are many genes that contribute to female pattern hair loss, and these genes could be inherited from one or both of your parents. However, some women with female pattern baldness do not have any paternal or maternal family history of baldness. Genetic testing to assess the risk of balding is currently not recommended, as it is unreliable.

These tips may help you avoid preventable types of hair loss:

- Be gentle with your hair. Use a detangler and avoid tugging when brushing and combing, especially when your hair is wet. A wide-toothed comb might help prevent pulling out hair. Avoid harsh treatments such as hot rollers, curling irons, hot-oil treatments and permanents. Limit the tension on hair from styles that use rubber bands, barrettes and braids.

- Shampooing and other hair products have no adverse effects other than harsh products or practices that may damage the hair shaft, causing breakage.

- Ask your doctor about medications and supplements you take that might cause hair loss.

- Protect your hair from sunlight and other sources of ultraviolet light.

- Stop smoking. Some studies show an association between smoking and baldness in men.

- If you’re being treated with chemotherapy, ask your doctor about a cooling cap. This cap can reduce your risk of losing hair during chemotherapy.

Thinning hair and hair loss in women signs and symptoms

In female pattern hair loss, there is diffuse thinning of hair over the top (crown) and the sides of head with retention of the frontal hairline due to increased hair shedding or a reduction in hair volume, or both. Total hair loss is very rare. Female pattern hair loss presents quite differently from the more easily recognizable male pattern baldness, which usually begins with a receding frontal hairline that progresses to a bald patch on top of the head. It is very uncommon for women to bald following the male pattern unless there is excessive production of androgens in the body.

Hair thinning is different from that of male pattern baldness. In female pattern baldness:

- Hair thins mainly on the top and crown of the scalp. It usually starts with a widening through the center hair part.

- The front hairline remains unaffected except for normal recession, which happens to everyone as time passes.

- The hair loss rarely progresses to total or near total baldness, as it may in men.

- If the cause is increased androgens, hair on the head is thinner while hair on the face is coarser.

Itching or skin sores on the scalp are generally not seen.

Thinning hair and hair loss in women diagnosis

Talk to your doctor if your hair is thinning. Your doctor will examine your hair and scalp, and might refer you to a dermatologist, a doctor who specializes in skin problems. Your doctor can often diagnose female pattern baldness on clinical grounds without a scalp biopsy. However, your doctor may suggest a biopsy to rule out other hair loss conditions that can mimic female pattern baldness.

Female pattern baldness is usually diagnosed based on:

- Ruling out other causes of hair loss.

- The appearance and pattern of hair loss.

- Your medical history.

If you have acne, irregular periods or a lot of body hair, your doctor might recommend a test to check your hormones, or to rule out polycystic ovarian syndrome (PCOS). Blood tests include female and male sex hormone levels as well as thyroid function, are part of the diagnostic workup.

Your doctor might also recommend removing a tiny piece of skin from your scalp (skin biopsy) to test for hair loss conditions such as alopecia areata. Scalp biopsy is the most reliable test to differentiate female pattern hair loss from chronic telogen effluvium by evaluation of terminal:vellus hair ratio. A terminal:vellus hair ratio of <4:1 is diagnostic of female pattern hair loss and a ratio of >8:1 is diagnostic of chronic telogen effluvium 28.

Your health care provider will examine you for other signs of too much male hormone (androgen), such as:

- Abnormal new hair growth, such as on the face or between the belly button and pubic area

- Changes in menstrual periods and enlargement of the clitoris

- New acne

A skin biopsy of the scalp or blood tests may be used to diagnose skin disorders that cause hair loss.

The European Consensus held in 2011 recommends the free androgen index (FAI) and prolactin levels as screening tests 32. The free androgen index (FAI) is the relationship between total testosterone and sex hormone-binding globulin (SHBG) [total testosterone (nmol/L)/SHBG (nmol/L) × 100]. The free androgen index (FAI) of 5 or greater is indicative of polycystic ovary syndrome (PCOS). The use of hormonal contraceptives causes alterations in sex hormone-binding globulin (SHBG) levels. Therefore, laboratory tests should only be carried out after a hormonal contraceptive pause of at least 2 months. Thyroid function should be evaluated as thyroid dysfunctions may contribute to the effluvium associated with female pattern hair loss [32.

Looking at the hair with a dermoscope (trichoscopy) or under a microscope may be done to check for problems with the structure of the hair shaft itself. The main dermoscopic finding is the diversity in the thickness of the hairs with an increased number of miniaturized hairs, especially in the frontoparietal region (Figure 11). Hair diameter density >20% is diagnostic for female pattern hair loss. Short vellus hair (<0.03 mm) is a sign of severe miniaturization and their presence on the frontal scalp is a very useful clue for female pattern hair loss. A decrease in the number of hairs per follicular unit is another important element 33. The peripilar sign, a light brown area, slightly atrophic around the follicle, usually occurs in the early stages of female pattern hair loss which correlates with the inflammatory infiltrate. It can be brown sign, which is seen in early grades of female pattern hair loss and white peripilar sign, seen in later grades 34. Yellow dots may be seen in more advanced cases, probably as a result of sebum and keratin accumulation in dilated follicles. With increased thinning of the hairs, there is greater penetration of ultraviolet radiation into the scalp and changes typical of photoaging, such as the honeycomb pigmented network, may occur. These signs, when evaluated together, allow the early diagnosis of female pattern hair loss. In 2009, Rakowska standardized the criteria for the diagnosis of female pattern hair loss based on dermoscopic findings 35.

The majority of women affected by female pattern hair loss do not have underlying hormonal abnormalities. However, a few women with female pattern hair loss are found to have excessive levels of androgens. These women also tend to suffer from acne, irregular menses and excessive facial and body hair. These symptoms are characteristic of the polycystic ovarian syndrome (PCOS) although the majority of women with PCOS do not experience hair loss. Less often, congenital adrenal hyperplasia may be responsible.

Figure 11. Trichoscopy of female pattern hair loss

Footnote: Trichoscopy of female pattern hair loss showing peripilar sign (black circle), yellow dots (red arrow), focal atrichia (white square), single hairs and honeycomb pigmentation in the background. Presence of hair of various diameters indicates increased hair diameter diversity.

[Source 28 ]Hair loss treatment for women

Treatments are available for female pattern hair loss although there is no cure. The main aim of treatment is to slow down or stop your hair loss. Treatment might also stimulate hair growth, but this kind of treatment works better for some women than others. Results are variable, and it is not possible to predict who may or may not benefit from treatment.

Medicines

The only medicine approved by the United States Food and Drug Administration (FDA) to treat female pattern baldness is minoxidil:

- It is applied to the scalp.

- For women, the 2% solution or 5% foam is recommended.

- Minoxidil may help hair grow in about 1 in 4 or 5 of women. In most women, it may slow or stop hair loss.

- You must continue to use this medicine for a long time. Hair loss starts again when you stop using it. Also, the hair that it helps grow will fall out.

Minoxidil 2% is the only treatment approved by the U.S. Food and Drug Administration (FDA) for treating female pattern hair loss in women older than 18 years. Topical minoxidil; the 2% preparation recommended for women is available over the counter. This may help hair to grow in a quarter of the women using it, and it will stop or slow hair loss in the majority of users. A Cochrane systematic review published in 2012 36 concluded that minoxidil solution was effective for female pattern hair loss. This updated 2016 Cochrane review found that minoxidil is more effective than placebo for female pattern hair loss or female androgenic alopecia 37. Minoxidil is available as 2% and 5% solutions; the stronger preparation is more likely to irritate and may cause undesirable hair growth unintentionally on areas other than the scalp. Furthermore, the updated 2016 Cochrane review found no difference in effect between the minoxidil 2% and 5% for female pattern hair loss 37.

It takes about 4 months of using minoxidil to see any obvious effect. You might have some hair loss for the first couple of weeks as hair follicles in the resting phase are stimulated to move to the growth phase. You need to keep using minoxidil to maintain its effect – once you stop treatment the scalp will return to its previous state of hair loss within 3 to 4 months. Also, be aware that minoxidil is not effective for all women, and the amount of hair regrowth will vary among women. Some women experience hair regrowth while in others hair loss is just slowed down. If there is no noticeable effect after 6 months, it’s recommended that treatment is stopped.

Always carefully follow the directions for use, making sure you use minoxidil only when your scalp and hair are completely dry. Take care when applying minoxidil near the forehead and temples to avoid unwanted excessive hair growth. Wash your hands after use.

The most common side effects of minoxidil include a dry, red and itchy scalp. Higher-strength solutions are more likely to cause scalp irritation.

Bear in mind that minoxidil is also used in tablet form as a prescription medicine to treat high blood pressure, and there is a small chance that minoxidil solution could possibly affect your blood pressure and heart function. For this reason, minoxidil is generally only recommended for people who do not have heart or blood pressure problems.

Minoxidil should not be used if you are pregnant or breast feeding.

If minoxidil does not work, your doctor may recommend other medicines, such as spironolactone, cimetidine, birth control pills, ketoconazole, among others. Your doctor can tell you more about these if needed.

There is not enough evidence to show that laser treatments, platelet-rich plasma injections, ‘hair tonics’ and nutritional supplements will stimulate hair growth. The true value of commercially available hair tonics and nutritional supplements claiming to treat female pattern baldness is also dubious.

Hormonal treatment, i.e. anti-androgen medicines are oral medications that block the effects of androgens (e.g. spironolactone, cyproterone acetate, finasteride and flutamide) is also often tried. These medicines help stop hair loss and may also stimulate hair regrowth. Spironolactone has been shown to stop the loss of hair in 90 per cent women with androgenetic alopecia. In addition, partial hair regrowth occurs in almost half of treated women. The effects of treatment generally only last while you continue to take the medicine – stopping the medicine will mean that your hair loss will return. Spironolactone and cyproterone acetate should not be taken during pregnancy. Effective contraception must be used while you are being treated with these medicines, as it can affect a developing baby. These medicines should also not be taken if you are breast feeding.

A hyperandrogenic state may limit the success of treatment with minoxidil 38 and, in these women, spironolactone (Aldactone) 100 to 200 mg daily may slow the rate of hair loss 39. Women with evidence of a hyperandrogenic state requesting combined oral contraceptives would benefit from using antiandrogenic progesterones, such as drospirenone 40. Finasteride (Propecia) is ineffective in postmenopausal women with female pattern hair loss 41. Finasteride, spironolactone, and cyproterone should not be used in women of childbearing potential.

Topical finasteride (used on the skin only) has not been approved by the U.S. Food and Drug Administration (FDA), but has been approved in India to treat male and female pattern hair loss 42. Topical finasteride has been found to be as effective as oral finasteride 43, 44, 45, 46. A recent single-center, double-blind randomized controlled trial compared the efficacy between topical 3% minoxidil solution alone and in combination with 0.25% finasteride for treatment of 30 postmenopausal female pattern hair loss patients 47. The combined treatment group showed significantly superior results compared to the minoxidil monotherapy group in terms of increased hair diameter at weeks 24, while increased hair density was progressively observed over time from weeks 8 in both groups with similar time-courses 47. At week 24, clinical improvements as assessed by global photographic assessment from blinded dermatologists and participants were reported in approximately 93% of participants in the combined treatment group but were not significantly different from the minoxidil group 47. The authors agreed with the previous literature that adding 0.25% finasteride to minoxidil solution showed evidence of systemic absorption by lowering serum dihydrotestosterone (DHT) level after 24 weeks of treatment 47. Nevertheless, DHT (dihydrotestosterone) levels remained in the normal range throughout the study 47. This study showed that topical finasteride is a promising treatment for post-menopausal women with female pattern hair loss. However, many aspects of topical finasteride are required for further investigations, including delivery systems, concentrations, and application regimens. Minimal local side effects such as pruritus and irritation have been reported with topical finasteride 47. Because of limited data, further clinical trials with long-term use should be performed to confirm the safety of topical finasteride in women.

A combination of low dose oral minoxidil (eg, 2.5 mg daily) and spironolactone (25 mg daily) has been shown to significantly improve hair growth, reduce shedding and improve hair density.

Once started, treatment needs to continue for at least six months before the benefits can be assessed, and it is important not to stop treatment without discussing it with your doctor first. Long term treatment is usually necessary to sustain the benefits.

Side effects of spironolactone can include:

- irregular periods and spotting;

- breast tenderness or lumpiness; and

- tiredness.

Side effects of cyproterone acetate can include:

- spotting and irregular periods;

- tiredness;

- weight gain;

- reduced libido; and

- depressed mood.

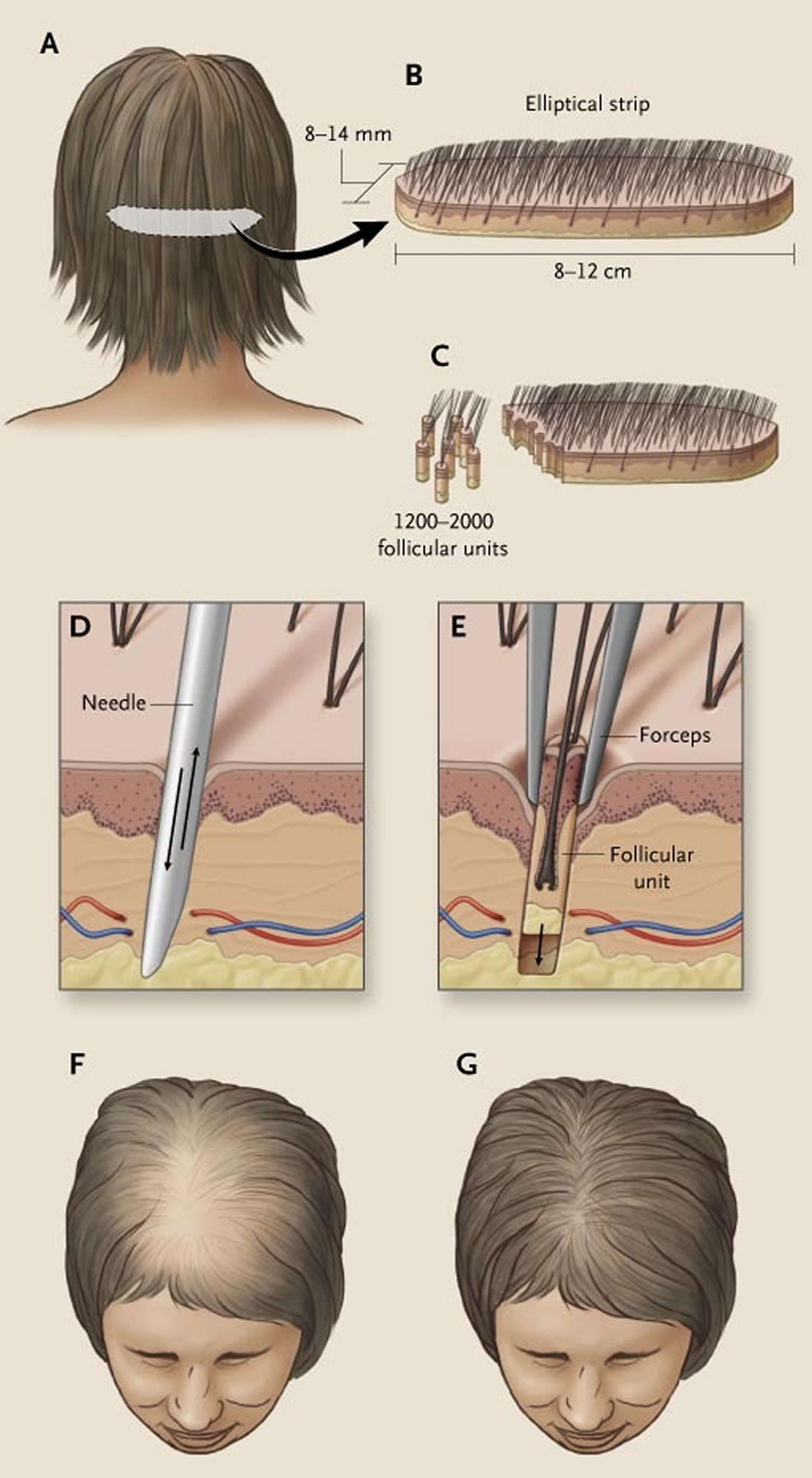

Cosmetic camouflages include colored hair sprays to cover thinning areas on the scalp, hair bulking fiber powder, and hair wigs. Hair transplantation for female pattern hair loss is becoming more popular although not everyone is suitable for this procedure. Your doctor can refer you to a hair transplant surgeon to assess whether hair transplant surgery may be a suitable option for you.

Hair transplant surgery involves follicular unit transplantation, where tiny clusters of hair-producing tissue (each containing up to 4 hairs) are taken from areas of the scalp where hair is growing well and surgically attached (grafted) onto thinning areas. However, if your hair is very thin all over your scalp, you may not have enough healthy hair to transplant.

Hair transplant surgery can be expensive and painful, and multiple procedures are sometimes needed. Side effects may include infection and scarring.

Low-level laser therapy (LLLT) is of unproven benefit in female pattern balding; the Capillus® laser cap and Hairmax® Lasercomb/Laserband are two low‐level laser therapy (LLLT) devices have been approved by the FDA for the management of androgenetic alopecia 48, 49, 50. In a randomized, double‐blind, placebo‐controlled trial comprising 42 female subjects with androgenetic alopecia, 24 active group subjects were treated with 655 nm low-level laser therapy (LLLT) vs. 18 placebo group subjects were treated with incandescent red lights (sham) 48. Subjects were treated on alternate days for 16 weeks, and photography and hair count assessments revealed a 37% increase in terminal hair counts in the active treatment group as compared to the control group. In a review of 11 trials, 10 demonstrated significant improvement in androgenetic alopecia compared to baseline or controls when treated with low-level laser therapy (LLLT) 51. Two of the trials demonstrated efficacy for low-level laser therapy (LLLT) in combination with topical minoxidil, and one trial showed efficacy in combination with finasteride 52. Small number of participants reported adverse events of acne, mild paresthesia such as burning sensation, dry skin, headache, and itch 51.

Overall, literature has suggested light therapy to be a safe treatment modality for androgenic alopecia (androgenetic alopecia) in both male and female patients when used independently or in combination with topical/oral therapies 51, 53. Light therapy has an excellent side effect profile, and there are no contraindications for use, although caution may be taken when administering in patients with dysplastic lesions on the scalp 54.

Platelet‐rich plasma (PRP) injections are also under investigation 55. Further studies are required to determine the magnitude of the benefit if any.

Platelet‐rich plasma is generally indicated for patients with early‐stage androgenic alopecia, as intact hair follicles are present and a more significant hair restorative effect can be achieved 52. During the procedure, approximately 10–30 mL of blood are drawn from the patient’s vein and centrifuged for 10 min in order to separate the plasma from red blood cells. The platelet‐rich plasma, containing numerous growth factors, is then injected into the deep dermis or subcutaneous tissue at a volume of 4–8 mL per session. Mild side effects include scalp pain, headache, and burning sensation, but these effects usually subside in 10–15 minutes post‐injection and do not warrant use of topical anesthesia or pain medications 56. Vibration or cool air is typically sufficient to alleviate any significant pain that a patient may feel from the treatment. Patients can resume regular activities immediately after treatment but should avoid strenuous physical activity 24 hour post‐treatment to allow for optimal absorption of platelet‐rich plasma into tissue.

Hausauer and Jones 57 conducted a single center, blinded, randomized controlled trial investigating the efficacy of two platelet‐rich plasma regimens in 40 androgenic alopecia subjects. Participants received either subdermal platelet‐rich plasma injections with 3 monthly sessions and booster 3 months later (group 1) or 2 sessions every 3 months (group 2). Folliscope hair count and shaft caliber, global photography, and patient satisfaction questionnaires were completed at baseline, 3‐month, and 6‐month visits. The authors reported statistically significant increases in hair count and shaft caliber in both groups at 6 months. Importantly, improvements occurred more rapidly and profoundly in group 1, indicating that platelet‐rich plasma injections should be administered first monthly 57. Alves and Grimalt 58 demonstrated significant differences in mean anagen hair and telogen hair count as well as telogen and overall hair density when compared to baseline. In a review of 16 studies comprising a total of 389 patients with androgenic alopecia, the majority demonstrated efficacy in promoting successful hair growth after 3–4 sessions on a monthly basis, followed by quarterly maintenance sessions 59. Platelet‐rich plasma is not curative for hair loss and must be continued long term for hair sustenance. However, patient satisfaction is typically very high and 60–70% of patients continue to undergo maintenance treatments. Due to the relatively recent introduction of platelet‐rich plasma injections for androgenic alopecia, there are no long‐term studies evaluating its effectiveness. Additionally, it is difficult to compare the efficacy with other remedies due to the lack of standardization in regard to platelet‐rich plasma kits, treatment fractions, and regimens, including the use of newer multi‐needle injectors.

While platelet‐rich plasma injections are considered safe when performed by a trained medical provider, these treatments are not suitable for everyone. Platelet‐rich plasma may not be appropriate for those with a history of bleeding disorders, autoimmune disease, or active infection, or those currently taking an anticoagulant medication. Although the majority of patients seem to tolerate the pain associated with scalp injections, some patients may prefer to avoid it.

Topical Minoxidil

Minoxidil is a medicated solution you apply to the scalp to help stop hair loss. Topical 2% minoxidil solution is approved by the Food and Drug Administration (FDA) for women with thinning hair due to female-pattern hair loss. It may also stimulate hair regrowth in some women. Brand names include Regaine for Women and Hair A-Gain. Minoxidil for hair loss is available over-the-counter from pharmacies – you don’t need a prescription.

It takes about 4 months of using minoxidil to see any obvious effect. You might have some hair loss for the first couple of weeks as hair follicles in the resting phase are stimulated to move to the growth phase.

You need to keep using minoxidil to maintain its effect – once you stop treatment the scalp will return to its previous state of hair loss within 3 to 4 months. Also, be aware that minoxidil is not effective for all women, and the amount of hair regrowth will vary among women. Some women experience hair regrowth while in others hair loss is just slowed down. If there is no noticeable effect after 6 months, it’s recommended that treatment is stopped.

Always carefully follow the directions for use, making sure you use minoxidil only when your scalp and hair are completely dry. Take care when applying minoxidil near the forehead and temples to avoid unwanted excessive hair growth. Wash your hands after use.

In a double-blind, placebo-controlled trial, 2% minoxidil used twice daily resulted in minimal hair regrowth in 50% of women and moderate hair regrowth in 13% of women after 32 weeks of treatment, as compared with rates of 33% and 6%, respectively, in the placebo group 60. Efficacy can be assessed definitively after 6 to 12 months of treatment. Side effects of topical minoxidil therapy include contact dermatitis (attributed in many cases to irritation from propylene glycol in the solution) and symmetric facial hypertrichosis manifested as fine hairs on the cheeks or forehead in up to 7% of women. Hypertrichosis disappears within 4 months after discontinuation of the drug. Minoxidil should not be used in pregnant or nursing women.

The use of 5% minoxidil may be considered in women who do not have a response to the 2% formulation or who want more aggressive management 61. A double-blind, randomized trial comparing a 5% minoxidil solution with a 2% minoxidil solution used twice daily in women with mild-to-moderate female-pattern hair loss showed no significant difference between the two solutions with respect to investigator assessments of efficacy, but it showed significantly greater patient satisfaction with the 5% preparation 61. However, the incidences of hypertrichosis (excessive hair growth) and contact dermatitis were higher with the 5% solution than with the 2% solution. A new 5% minoxidil foam formulation that contains no propylene glycol appears to be much less likely to cause contact dermatitis than topical minoxidil solution. Although they are prescribed by many dermatologists in practice, neither the 5% minoxidil solution nor the foam preparation is FDA-approved for use in women 62.

Side effects associated with minoxidil

The most common side effects of minoxidil include a dry, red and itchy scalp. Higher-strength solutions are more likely to cause scalp irritation.

Bear in mind that minoxidil is also used in tablet form as a prescription medicine to treat high blood pressure, and there is a small chance that minoxidil solution could possibly affect your blood pressure and heart function. For this reason, minoxidil is generally only recommended for people who do not have heart or blood pressure problems.

Minoxidil should not be used if you are pregnant or breast feeding.

Oral Minoxidil

Although not FDA‐approved and not nearly as popular as topical minoxidil, multiple studies were conducted to evaluate oral minoxidil for treating both male and female patients with androgenetic alopecia. Oral minoxidil is available as a 2.5 mg tablet, and it can be cut in halves or quarters to achieve optimal safe dosing for the treatment of androgenetic alopecia. Sinclair first reported the combination of oral minoxidil 0.25 mg and spironolactone 25 mg to be a safe and effective option in managing female pattern hair loss 63.

Several retrospective case series reported oral minoxidil to be an effective treatment for female androgenetic alopecia with favorable side effects 64, 65. Studies suggested that optimal safe doses range between 0.625 mg and 1.25 mg daily 66. Oral minoxidil has also shown equivalent effectiveness in women compared to the 5% topical formulation 67. Jimenez‐Cauhe et al. 68 conducted a retrospective review of 41 men diagnosed with androgenetic alopecia undergoing oral minoxidil 5 mg daily treatment. Side effects were detected in about 30% of the participants, but they were all tolerable 68. Another prospective study 69 using a 5 mg once daily regimen showed 100% improvement at week 12 and 24 with 43% patients achieving excellent improvement. Pirmez et al. 70 suggested that very low dose oral minoxidil (0.25 mg once daily) may be less effective in treating moderate androgenetic alopecia and higher dosage might be needed. However, the sample size was small.

Side effects oral minoxidil

Although it may be more convenient for patients to take the oral form of minoxidil, its systemic side effects such as increased heart rate, weight gain, hirsutism, hypertrichosis, and lower extremity edema make it unfavorable compared to topical minoxidil as a first‐line treatment 69. In a recent study of 1404 subjects 71, the most common side effect was noted to be hypertrichosis in about 15% of patients and the incidence of systemic adverse effects was noted in 1.7% of patients. Oral minoxidil’s side effects, however, are typically dose‐dependent and reversible with discontinuation of the drug. Rare side effects include pericardial effusion, congestive heart failure, and allergic reactions 69.

Anti-androgen medicines

Antiandrogen agents (including the androgen-receptor blockers spironolactone, cyproterone acetate, and flutamide and the type II 5 alpha-reductase inhibitor finasteride) and oral contraceptives are not commonly used to treat female-pattern hair loss in North America, but they are used more commonly in Europe 62. None of these agents are FDA-approved for female-pattern hair loss. Cyproterone acetate is not approved in the United States, and neither flutamide nor finasteride is approved for any indication in women, although finasteride is approved for the treatment of hair loss in men.

Spironolactone and cyproterone acetate (brand names include Androcur, Cyprone and Cyprostat) are anti-androgen medicines that may be prescribed to treat female pattern hair loss.

These medicines help stop hair loss and may also stimulate hair regrowth. Spironolactone has been shown to stop the loss of hair in 90 per cent women with androgenetic alopecia. In addition, partial hair regrowth occurs in almost half of treated women.

The effects of treatment generally only last while you continue to take the medicine – stopping the medicine will mean that your hair loss will return.

Spironolactone and cyproterone acetate should not be taken during pregnancy. Effective contraception must be used while you are being treated with these medicines, as it can affect a developing baby. These medicines should also not be taken if you are breast feeding.

In an open-label study of cyproterone acetate (50 to 100 mg daily for 10 days of the menstrual cycle) or spironolactone (200 mg daily) in women with female-pattern hair loss, more than 80% of women had either hair regrowth or stabilization of hair loss, but this study was uncontrolled 72. In a randomized trial comparing topical 2% minoxidil solution plus an oral contraceptive with cyproterone acetate (52 mg per day) plus an oral contraceptive in women with female-pattern hair loss, the latter combination resulted in greater hair density in women with hyperandrogenism, whereas in women without hyperandrogenism, minoxidil had a greater effect 73. If antiandrogen agents are used in women of reproductive age, an oral contraceptive should be prescribed concomitantly, since these agents are known teratogens. Teratogens are substances that may produce birth defects in the human embryo or fetus after the pregnant woman is exposed.

In two small, uncontrolled studies, finasteride (Propecia) at a minimum dose of 2.5 mg per day appeared to have a benefit for women with female-pattern hair loss 74, 75. However, in a double-blind, controlled trial involving postmenopausal women with female-pattern hair loss, treatment with finasteride at a dose of 1 mg per day was not significantly better than placebo. Like the antiandrogens, finasteride is a known teratogen and is classified as pregnancy category X, that it is contradicted in women who are or may become pregnant, and its use is not recommended in women of reproductive age 76. An animal study showed that finasteride led to dose-dependent development of hypospadias in male offspring, and that the abnormal development of external genitalia is an expected aftereffect from inhibition of type II 5α-reductase similar to male children with genetic 5α-reductase deficiency 77. No developmental abnormalities were seen in female fetuses. Finasteride is also prohibited in lactating women because of its potential risks in male infants, despite the unavailability of data on its excretion in human milk. Finasteride can interfere with the estrogen/testosterone balance, leading to potential risk of estrogen-mediated malignant transformation; it should be avoided in those who have family history of breast cancer 78.

Side effects of anti-androgen medicines

Side effects of spironolactone can include:

- irregular periods and spotting;

- breast tenderness or lumpiness; and

- tiredness.

Side effects of cyproterone acetate can include:

- spotting and irregular periods;

- tiredness;

- weight gain;

- reduced libido; and

- depressed mood.

Spironolactone

Although labeled for the treatment of cardiovascular diseases, spironolactone has been widely used as a treatment for female pattern hair loss due to its antiandrogenic properties 52. Spironolactone works by decreasing testosterone production in the adrenal gland by affecting the 17a‐hydroxylase and desmolase, as well as the competitive inhibitor of the androgen receptor 23. Spironolactone is the most commonly used antiandrogen for female pattern hair loss and the standard dose is 100–200 mg daily 79. A clinical trial conducted by Sinclair et al. 80 studied 80 female patients with either cyproterone acetate or spironolactone 200 mg daily and found that 44% subjects experienced hair regrowth, 44% had no change in their hair density, and 12% had reduced hair density. There was no significant difference between both treatment groups 80. There were also case reports demonstrating the effectiveness of spironolactone alone or when combined with topical minoxidil 81, 82. In a retrospective survey of 166 patients with female-pattern hair loss being managed with spironolactone, over 70% of patients noted stabilization or improvement of their disease 83.

Side effects of spironolactone

Although well‐tolerated and has been on the market for decades, the side effects of spironolactone include electrolyte imbalance, worsening of kidney function, and hypotension (low blood pressure).

Cyproterone acetate

Cyproterone acetate inhibits gonadotrophin secretion and cutaneous 5‐alpha‐reductase activity and inhibits the androgen receptor 84. Cyproterone acetate is not available in the United States, but has been used in other countries for female pattern hair loss. It has shown efficacy in treating androgenic alopecia and acne vulgaris in female patients 85. Although cyproterone acetate and topical minoxidil are both safe and effective options, cyproterone acetate may be a superior choice when patients have other signs of hyperandrogenism and elevated body mass index (BMI) 84, 86.

Side effects of cyproterone acetate

Cyproterone acetate is associated with weight gain, breast tenderness, and decreased sex drive (libido).

Flutamide and bicalutamide

Flutamide is an oral antiandrogen medication rarely used in clinical practice. Oral flutamide first reported to be an appropriate option for managing hyperandrogenic alopecia 87. Oral flutamide 250 mg daily was noted to be effective in managing female pattern hair loss refractory to topical minoxidil and oral spironolactone in a 55‐year‐old female 88. A large population study evaluated yearly reduction of oral flutamide in managing androgenic alopecia. A significant decrease in alopecia score was seen and 4% of the patients dropped out the study in the initial phase due to liver toxicity 89. No patients abandoned the study in the following year when they were treated with a lower dose. Other common side effects of flutamide include hot flashes and potentially increasing the effect of warfarin 90.

Bicalutamide is a nonsteroidal, antiandrogen medication. It has a more favorable safety profile than flutamide when treating prostate cancer. Recent retrospective review study of 17 women given oral bicalutamide with or without adjuvant therapies showed oral bicalutamide as a useful option in treatment of female pattern hair loss, especially patients with other comorbidities such as polycystic ovarian syndrome or hirsutism 91.

Side effects of flutamide and bicalutamide

Flutamide carries a risk of liver injury and has a Black box warning of liver failure. The most common side effect of bicalutamide is mild and transient elevation of liver enzymes 91. Two retrospective reviews also suggested bicalutamide as a safe and effective option for female pattern hair loss with 95% adherence 92, 93. The most common side effects of oral bicalutamide were mild liver injury, peripheral edema, and gastrointestinal complaints. A retrospective review of oral bicalutamide reported three and four out of 316 patients dropped out of the study due to elevated liver enzymes and gastrointestinal discomfort, respectively 93.

Hair transplant

Your doctor can refer you to a dermatologist or hair transplant surgeon to assess whether hair transplant surgery may be a suitable option for you. Talk to your doctor about the risks and benefits of this treatment.

Hair transplant surgery involves follicular unit transplantation, where tiny clusters of hair-producing tissue (each containing up to 4 hairs) are taken from areas of the scalp where hair is growing well and surgically attached (grafted) onto thinning areas. However, if your hair is very thin all over your scalp, you may not have enough healthy hair to transplant. Hair transplant surgery can be expensive and painful, and multiple procedures are sometimes needed, which can be expensive. Side effects may include skin infection and scarring. However, the results are often excellent and permanent.

Surgical hair transplantation is increasingly used to treat many women with female-pattern hair loss 94. Clinical experience indicates that when the newer technique of follicular-unit transplantation is performed by an experienced surgeon, a natural result is possible 62. However, data on long-term outcomes are lacking, and rates of graft failure, although considered to be very low, remain uncertain. Costs vary, but they may range from $4,000 to $15,000 per session, depending on the size of the area treated and the surgeon. One or two sessions are usually sufficient for a cosmetically acceptable result. Hair density in the donor (occipital) area must be sufficient to yield the required number of grafts with no visible scarring. Complications, which are rare, include infection, permanent scalp dysthesias, and arteriovenous malformations (which occur in less than 1% of patients). Many surgeons use minoxidil therapy in patients who have undergone hair transplantation, although this strategy has also not been rigorously studied 95.

Figure 12. Hair transplantation with grafts obtained from an elliptical strip from the back of the scalp

Footnote: An elliptical strip averaging in size from 8 to 14 mm wide and 8 to 12 cm long is excised from the occipital portion of the scalp (Panels A and B). This strip is subdivided into 1200 to 2000 follicular units of two to three hairs each (Panel C). Slits are made with a tiny spear or needle (Panel D). The needle is then removed, and follicular units are planted in these slits (Panel E). With appropriate placement and orientation of follicular units, it is possible to increase hair density from Ludwig stage II (Panel F) to Ludwig stage I (Panel G) in a patient with female-pattern hair loss.

Other solutions

The following cosmetic treatments for hair loss are available for women with female pattern baldness.

- Hair bulking fiber powder, such as natural keratin fiber, is an inexpensive treatment that involves applying tiny, microfiber ‘hairs’ that bond to existing hair through static electricity to give the appearance of thicker hair.

- Coloring the scalp with a camouflage dye, or colored hair spray.

- A special type of tattooing called scalp micropigmentation or dermatography may be recommended in some cases where the hair is thinning to give the appearance of thicker hair.

- Synthetic and real hair wigs are available for those with severe hair loss.

Wigs and hair pieces

Some affected individuals find wigs, toupees and even hair extensions can be very helpful in disguising androgenetic alopecia female. There are two types of postiche (false hairpiece) available to individuals; these can be either synthetic or made from real hair. Synthetic wigs and hairpieces, usually last about 6 to 9 months, are easy to wash and maintain, but can be susceptible to heat damage and may be hot to wear. Real hair wigs or hairpieces can look more natural, can be styled with low heat and are cooler to wear.

Skin camouflage

Spray preparations containing small pigmented fibers are available from the internet and may help to disguise the condition in some individuals. These preparations however, may wash away if the hair gets wet (i.e. rain, swimming, perspiration), and they only tend to last between brushing/shampooing.

Unproven treatments

Hair loss remedies that have not yet been shown or proven to be effective include:

- laser treatment;

- nutritional supplements;

- platelet-rich plasma injections (also referred to as PRP rejuvenation);

- scalp massage; and

- acupuncture.

Some hair loss clinics and alternative medicine practitioners offer unproven treatments for hair loss. Make sure you understand exactly what is involved with any hair loss treatment and whether there is any proven scientific evidence for its effectiveness.

Discuss with your doctor the risks and benefits of any treatments that you are interested in before trying them. This will help you avoid spending money on a treatment that is unlikely to help and may involve side effects.

Your doctor can refer you to a specialist dermatologist for an expert opinion on current treatments that have been shown to be safe and effective.

Scalp massage

Developing hair follicles are surrounded by deep dermal vascular plexuses. Associated blood vessels function to supply nutrients to the developing hair follicle and foster waste elimination. As such, proper blood supply is necessary for effective hair follicle growth, further exemplified by the angiogenic properties of the anagen phase 96. A 2016 study 97 assessed the effect of a 4-minute standardized daily scalp massage for 24 weeks among nine healthy men. Authors found scalp massage to increase hair thickness, upregulate 2655 genes, and downregulate 2823 genes; hair cycle-related genes including NOGGIN, BMP4, SMAD4, and IL6ST were among those upregulated, and hair-loss related IL6 was among those downregulated 97. The authors thereby concluded that a standardized scalp massage and subsequent dermal papilla cellular stretching can increase hair thickness, mediated by changes in gene expression in dermal papilla cells 97.

In addition, of 327 survey respondents attempting standardized scalp massages following demonstration video, 68.9% reported hair loss stabilization or regrowth 98. Positive associations existed between self-reported hair changes and estimated daily minutes, months, and total standardized scalp massage effort. This study 98 is limited based on recall bias and reliance on patient adherence and technique, although it suggests promising therapeutic potential for standardized scalp massage, which functions to increase blood flow.

Low-level laser (light) therapy

Low-level laser (light) therapy refers to therapeutic exposure to low levels of red and near infrared light 99. Studies have demonstrated increased hair growth in mice with chemotherapy-induced alopecia and alopecia areata, in addition to both men and women human subjects. Proposed mechanisms of efficacy include stimulation of epidermal stem cells residing in the hair follicle bulge and promoting increased telogen to anagen phase transition 100. Interestingly, while minoxidil and finasteride are the only FDA-approved drugs for androgenetic alopecia in men, a 2017 study 53 found comparable efficacy among patients receiving low-level light therapy versus topical minoxidil among patients with female-pattern androgenetic alopecia. In addition, combination therapy resulted in the greatest patient satisfaction and lowest Ludwig classification scores of androgenetic alopecia.

A meta-analysis including eleven double-blinded randomized controlled trials found a significant increase in hair density among patients with androgenetic alopecia receiving low level light therapy compared to those in the placebo-controlled group 101. Low level light therapy was effective for men and women. Furthermore, a subgroup analysis observed a more significant increase in hair growth in those receiving low-frequency therapy than receiving high-frequency therapy 101. Despite the limitation of the heterogeneity of included trials, these results suggest low level laser (light) therapy to be a promising therapeutic strategy for androgenetic alopecia 101, although further research is necessary to determine the optimal wavelength and dosimetric parameters for hair growth 100.

Prostaglandins

Latanoprost is a prostaglandin F2 agonist and has been shown to have a direct effect on hair growth and pigmentation in eyelashes and hair around the eyes 102. Clinically used to treat glaucoma, latanoprost was found to affect the hair follicles in the telogen phase and cause them to move to the anagen phase; this was supported by the increased number and length of eyelashes seen in patients using latanoprost 102. Subsequently, the application of latanoprost for patients experiencing alopecia was assessed in clinical studies. One conducted in 2012 studied the effects of 0.1% latanoprost solution applied to the scalp for 24 weeks 103. Participants included 16 males with mild androgenetic alopecia and were instructed to apply placebo on one area of the scalp and the treatment on another area. The results indicated that the area of scalp receiving latanoprost had significantly improved hair density compared to placebo 103.

Another prostaglandin known as bimatoprost, a prostamide-F2 analog, was also found to have a positive effect on hair growth in human and mouse models 104. A study conducted in 2013 also found that bimatoprost, in both humans and mice, stimulated the anagen phase of hair follicles prompting an increase in hair length, i.e., promoting hair growth 104. The study also confirmed the presence of prostanoid receptors in human scalp hair follicles in vivo, opening the strong possibility that scalp follicles can also respond to bimatoprost in a similar fashion 104.

It is important to note, however, that not all prostaglandins induce hair growth 105. In a study analyzing individuals with androgenetic alopecia with a bald scalp versus a haired scalp, it was discovered that there was an elevated level of prostaglandin D2 synthase at the mRNA and protein levels in bald individuals 105. They were also found to have an elevated level of prostaglandin D2 (PGD2). When analyzing the level of prostaglandin D2 synthase presence through the various phases of hair follicular growth, it was found that the level steadily increased throughout the anagen phase with a peak in late anagen, at the time of transition to the catagen (breakdown) phase. Therefore, the study concluded that prostaglandin D2 (PGD2)’s hair loss effect represents a counterbalance to PGE2 and PGF2’s hair growth effects. In conclusion, prostaglandins are a promising treatment option for alopecia that require larger clinical studies; however, clinicians should be aware of which one to recommend for hair growth, as not all prostaglandins are alike 21.

Platelet rich plasma

Platelet rich plasma (PRP) has conventionally been used to supplement a patient’s endogenous platelet supply to promote increased healing 21. However, its prominent supply of growth factors has prompted assessment of platelet rich plasma for alopecia. Growth factors promote hair growth and increase the telogen to anagen transition. For example, a mice study found the fibroblast growth factor (FGF) induced the anagen phase and subsequently promoted hair growth 106. Growth factors prominently included in platelet rich plasma include platelet-derived growth factor (PDGF), transforming growth factor β (TGF-β), vascular endothelial growth factor (VEGF), epidermal growth factor (EGF), insulin-like growth factor (IGF) and fibroblast growth factor (FGF) 107.

The growth factors of platelet-rich plasma stimulate the development of new follicles and neovascularization 108. Three meta-analyses have assessed the efficacy of platelet rich plasma injections compared to placebo control on the number of hairs per cm2 among patients with androgenetic alopecia. One meta-analysis involving 177 patients found a mean improvement of platelet rich plasma treatment compared to placebo of 17.9 109; a second meta-analysis with 262 androgenetic alopecia patients observed a mean difference of 38.8 110; and a third meta-analysis including studies with parallel or half-head design found a mean difference of 30.4 111.

Despite the efficacious results described by each meta-analysis for the use in androgenetic alopecia, gender differences have been observed. A 2020 meta-analysis 112 found that while platelet rich plasma significantly increased hair density and hair diameter from baseline in men, platelet rich plasma only increased hair diameter in women, in the absence of significantly increased hair density. Furthermore, hair density in men was only significantly increased by a double spin method, in contrast to a single spin method 112. The authors conclude that platelet rich plasma effectiveness may be improved via higher platelet concentrations 112. Ultimately, platelet rich plasma injections appear to have clinical efficacy in early studies although with slightly different effects in men vs. women. Future research is necessary to establish the optimal treatment protocol for both men and women with androgenetic alopecia. Also, the role of diet in the days prior to collection of the platelet rich plasma has not been assessed in conjunction with hair, although diet influences the quality of the platelet rich plasma 113.

Microneedling

Microneedling is a minimally invasive dermatologic procedure in which fine needles are rolled over the skin to puncture the stratum corneum. The physical trauma from needle penetration in microneedling induces a wound healing cascade with minimal damage to the epidermis stimulating collagen formation, neovascularization, and growth factor production in the treated areas 114. Microneedling enhances drug delivery in the treatment of androgenetic alopecia and female pattern hair loss and has been successfully paired with other hair growth-promoting therapies such as minoxidil, platelet-rich plasma, and topical steroidal medications 114.

Melatonin

Melatonin is known to have strong anti-oxidant properties and the ability to actively capture free radicals 115. Melatonin has been found to modulate hair growth, pigmentation, and molting in many species including humans 116. The topical application of the melatonin 0.1% solution was shown to significantly increase anagen hair in male and female androgenetic alopecia with good compliance in a controlled study 117.

Living with hair loss

Many studies have shown that hair loss is not merely a cosmetic issue, but it also causes significant psychological distress. For some women, hair loss can be incredibly distressing and can be associated with low self-esteem, depression, introversion, and feelings of unattractiveness. Others might accept their hair loss a little more easily.

Hair loss is especially hard to live in a society that places great value on youthful appearance and attractiveness. Compared to unaffected women, those affected have a more negative body image and are less able to cope with daily functioning.