Chlamydia trachomatis

Chlamydia trachomatis is a Gram-negative anaerobic intracellular bacterium that infects the columnar epithelium of the cervix, urethra, and rectum, as well as nongenital sites such as the lungs and eyes 1, 2. Chlamydia trachomatis is a member of the Chlamydiaceae family. The genus Chlamydia includes three species that infect humans: Chlamydia trachomatis, Chlamydia pneumoniae, and Chlamydia psittaci 1, 3.

Chlamydia trachomatis differentiates into 18 serovars (serologically variant strains) based on monoclonal antibody-based typing assays. These serovars correlate with multiple medical conditions as follows 4:

- Serovars A, B, Ba, and C: Trachoma is a serious ocular illness that is endemic in Africa and Asia. It is characterized by chronic conjunctivitis and has the potential to cause blindness

- Serovars D-K: Genital tract infections, neonatal infections

- Serovars L1-L3: Lymphogranuloma venereum (LGV), which correlates with genital ulcer disease in tropical countries.

Chlamydia trachomatis bacterium is the cause of the most frequently reported sexually transmitted disease (STD) in the United States, which is responsible for more than 1.6 million infections annually 5, 6. Most people with chlamydia infection are asymptomatic. Untreated infection can result in serious complications such as pelvic inflammatory disease (PID), cervicitis, infertility, chronic pelvic pain and ectopic pregnancy in women, and epididymitis and orchitis in men and urethritis and proctitis in both men and women. Men and women can experience chlamydia-induced reactive arthritis.

Lymphogranuloma venereum, another type of STD caused by different serovars of the same Chlamydia trachomatis bacterium, occurs commonly in the developing world, and has more recently emerged as a cause of outbreaks of proctitis among men who have sex with men worldwide 7. Lymphogranuloma venereum (LGV) generally presents as a unilateral, tender inguinal or femoral node, and may include a genital ulcer or papule. Anal exposure may result in proctocolitis, rectal discharge, pain, constipation, or tenesmus.If left untreated, it may lead to chronic symptoms, including fistulas and strictures. Diagnosis is based on clinical symptoms and a genital lesion swab or lymph node sample, similar to those used to diagnose the more typical C. trachomatis genitourinary infection. Molecular identification may be needed to differentiate lymphogranuloma venereum (LGV) from non-lymphogranuloma venereum (non-LGV) Chlamydia trachomatis. Doxycycline (100 mg twice daily for 21 days) is the preferred treatment. An alternative treatment regimen includes erythromycin (500 mg four times daily for 21 days); azithromycin (1 g once weekly for three weeks) may also be used 6.

According to the Centers for Disease Control and Prevention (CDC) in 2009, the rate of sexually transmitted chlamydia infections in the United States was 426 cases per population of 100,000, which represents a 24 percent increase in the rate of infection since 2006 8. More recent data from 2016 indicates that 1,598,354 chlamydia infections were reported to the CDC from all 50 states and the District of Columbia 9. The CDC estimates that there are 2.86 million chlamydia cases in the United States annually—more than twice the number actually reported 10. This is an increase of 5 percent over the past year, and 27 percent from four years ago 11. A large number of cases are not reported because most people with chlamydia are asymptomatic and do not seek testing.

Chlamydia is most common among young people, especially young women. Almost two-thirds of new chlamydia infections occur among youth aged 15-24 years 10. It is estimated that 1 in 20 sexually active young women aged 14-24 years has chlamydia 12.

Substantial racial/ethnic disparities in chlamydial infection exist, with prevalence among non-Hispanic blacks 5.6 times the prevalence among non-Hispanic whites 9. Chlamydia is also common among men who have sex with men. Among men who have sex with men screened for rectal chlamydial infection, positivity has ranged from 3.0% to 10.5% 13. Among men who have sex with men screened for pharyngeal chlamydial infection, positivity has ranged from 0.5% to 2.3% 14.

The Centers for Disease Control and Prevention (CDC) recommends chlamydia screening for:

- Sexually active women age 25 or younger. The rate of chlamydia infection is highest in this group, so a yearly screening test is recommended. Even if you’ve been tested in the past year, get tested when you have a new sex partner.

- Pregnant women. You should be tested for chlamydia during your first prenatal exam. If you have a high risk of infection — from changing sex partners or because your regular partner might be infected — get tested again later in your pregnancy.

- Women and men at high risk. People who have multiple sex partners, who don’t always use a condom or men who have sex with men should consider frequent chlamydia screening. Other markers of high risk are current infection with another sexually transmitted infection and possible exposure to an STD through an infected partner.

Screening and diagnosis of chlamydia is relatively simple. Chlamydia tests include:

- A urine test. A sample of your urine is analyzed in the laboratory for presence of this infection.

- A swab. For women, your doctor takes a swab of the discharge from your cervix for culture or antigen testing for chlamydia. This can be done during a routine Pap test. Some women prefer to swab their vaginas themselves, which has been shown to be as diagnostic as doctor-obtained swabs.

For men, your doctor inserts a slim swab into the end of your penis to get a sample from the urethra. In some cases, your doctor will swab the anus.

If you’ve been treated for an initial chlamydia infection, you should be retested in about three months.

Chlamydia trachomatis is treated with antibiotics (e.g., doxycycline, azithromycin or levofloxacin). You might receive a one-time dose, or you might need to take the medication daily or multiple times a day for five to 10 days.

In most cases, chlamydia infection resolves within one to two weeks. During that time, you should abstain from sex. Your sexual partner or partners also need treatment even if they have no signs or symptoms. Otherwise, the chlamydia infection can be passed back and forth between sexual partners.

Having chlamydia or having been treated for it in the past doesn’t prevent you from getting it again.

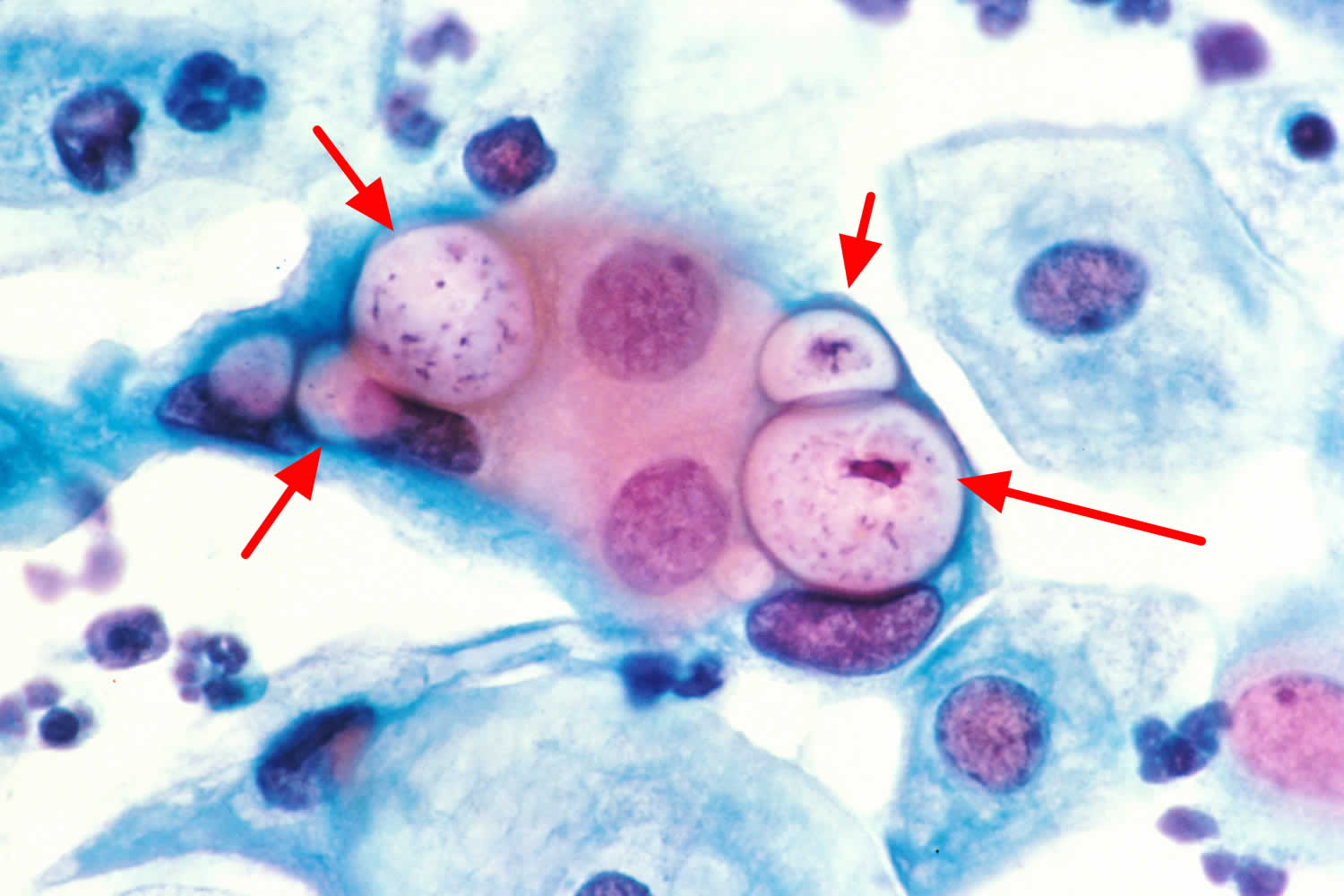

Figure 1. Chlamydia trachomatis bacteria (human pap smear showing cells infected with Chlamydia trachomatis at 500x magnification, stained with haematoxylin and eosin)

Chlamydia often has no symptoms, but it can cause serious health problems, even without symptoms. If symptoms occur, they may not appear until several weeks after having sex with a partner who has chlamydia.

See your doctor if you have a discharge from your vagina, penis or rectum, or if you have pain during urination. Also, see your doctor if you learn your sexual partner has chlamydia. Your doctor will likely prescribe an antibiotic even if you have no symptoms.

Chlamydia infection symptoms in women may include:

- An abnormal vaginal discharge; and

- A burning sensation when peeing.

Chlamydia infection symptoms in men may include:

- A discharge from their penis;

- A burning sensation when peeing; and

- Pain and swelling in one or both testicles (although this is less common).

Men and women can also get chlamydia in their rectum. This happens either by having receptive anal sex, or by spread from another infected site (such as the vagina). While these infections often cause no symptoms, they can cause:

- Rectal pain;

- Discharge; and

- Bleeding.

See a doctor if you notice any of these symptoms. You should also see a doctor if your partner has an STD or symptoms of one. Symptoms can include

- An unusual sore;

- A smelly discharge;

- Burning when peeing; or

- Bleeding between periods.

How does chlamydia spread?

You can get chlamydia by having vaginal, anal, or oral sex with someone who has chlamydia. If your sex partner is male you can still get chlamydia even if he does not ejaculate (cum).

If you’ve had chlamydia and were treated in the past, you can still get infected again. This can happen if you have unprotected sex with someone who has chlamydia.

If you are pregnant, you can give chlamydia to your baby during childbirth.

You are more likely to become infected with chlamydia if you have:

- Sex without using a condom

- Had multiple sexual partners

- Been infected with chlamydia before

Who should be tested for chlamydia?

Sexually active people can get chlamydia through vaginal, anal, or oral sex without a condom with a partner who has chlamydia. You should go to your doctor or a STD clinic for a test if you have symptoms of chlamydia or if you have a partner who has an STD. Pregnant women should get a test when they go to their first prenatal visit.

People at higher risk should get checked for chlamydia every year:

- Sexually active women 25 and younger

- Older women who have new or multiple sex partners or a sex partner who has an STD

- Men who have sex with men (MSM)

Sexually active young people are at a higher risk of getting chlamydia. This is due to behaviors and biological factors common among young people 15. Gay and bisexual men are also at risk since chlamydia can spread through oral and anal sex.

If you are sexually active, have an honest and open talk with your healthcare provider. Ask them if you should get tested for chlamydia or other STDs. Gay or bisexual men and pregnant people should also get tested for chlamydia.

STD clinic near you

Although it may be embarrassing, if you are sexually active, getting tested for STDs is one of the most important things you can do to protect your health. Make sure you have an open and honest conversation about your sexual history and STD testing with your doctor and ask whether you should be tested for STDs. If you are not comfortable talking with your regular health care provider about STDs, there are many clinics that provide confidential and free or low-cost testing. Below or following this link to find an STD testing center near you https://www.cdc.gov/std/prevention/screeningreccs.htm

Is there a cure for chlamydia?

Yes, antibiotics will cure chlamydia infection. You may get a one-time dose of the antibiotics, or you may need to take medicine every day for 7 days. It is important to take all the medicine that your doctor prescribed for you to cure your infection. When taken properly antibiotic will stop chlamydia infection and could decrease your chances of having problems later (see Chlamydia complications below). Antibiotics cannot repair any permanent damage that chlamydia has caused.

To prevent spreading chlamydia to your partner, you should not have sex until the chlamydia infection has cleared up. If you got a one-time dose of antibiotics, you should wait 7 days after taking the medicine to have sex again. If you have to take medicine every day for 7 days, you should not have sex again until you have finished taking all of the doses of your medicine.

It is common to get a repeat chlamydia infection, so you need to get tested again about three months after your treatment, even if your sex partner(s) receives treatment.

When can I have sex again after my chlamydia treatment?

You should not have sex again until you and your sex partner(s) complete treatment. If given a single dose of medicine, you should wait seven days after taking the medicine before having sex. If given medicine to take for seven days, wait until you finish all the doses before having sex.

If you’ve had chlamydia and took medicine in the past, you can still get it again. This can happen if you have sex without a condom with a person who has chlamydia.

What happens if I don’t get treated for chlamydia?

The initial damage that chlamydia causes often goes unnoticed. However, chlamydia can lead to serious health problems.

In women, untreated chlamydia can cause pelvic inflammatory disease (PID). Some of the complications of pelvic inflammatory disease are:

- Formation of scar tissue that blocks fallopian tubes;

- Ectopic pregnancy (pregnancy outside the womb);

- Infertility (not being able to get pregnant); and

- Long-term pelvic/abdominal pain.

Men rarely have health problems from chlamydia. The infection can cause a fever and pain in the tubes attached to the testicles. This can, in rare cases, lead to infertility.

Untreated chlamydia may also increase your chances of getting or giving HIV – the virus that causes AIDS.

I’m pregnant. How does chlamydia affect my baby?

If you are pregnant and have chlamydia, you can pass the infection to your baby during delivery. This could cause an eye infection or pneumonia in your newborn. Having chlamydia may also make it more likely to deliver your baby too early.

If you are pregnant, you should get tested for chlamydia at your first prenatal visit. Testing and treatment are the best ways to prevent health problems.

Can chlamydia be cured?

Yes, chlamydia can be cured with the right treatment. It is important that you take all of the medication your doctor prescribes to cure your infection. When taken properly it will stop the infection and could decrease your chances of having complications later on. You should not share medication for chlamydia with anyone.

Repeat infection with chlamydia is common. You should be tested again about three months after you are treated, even if your sex partner(s) was treated.

How can I reduce my risk of getting chlamydia?

The only way to avoid STDs is to not have vaginal, anal, or oral sex.

If you are sexually active, you can do the following things to lower your chances of getting chlamydia:

- Be in a long-term mutually monogamous relationship with a partner who has been tested and has negative STD test results;

- Use latex condoms the right way every time you have sex.

I was treated for chlamydia. When can I have sex again?

You should not have sex again until you and your sex partner(s) have completed treatment. If your doctor prescribes a single dose of medication, you should wait seven days after taking the medicine before having sex. If your doctor prescribes a medicine for you to take for seven days, you should wait until you have taken all of the doses before having sex.

Chlamydia trachomatis causes

Chlamydia is transmitted through sexual contact with the penis, vagina, mouth, or anus of an infected partner. Ejaculation does not have to occur for chlamydia to be transmitted or acquired. Chlamydia can also be spread perinatally from an untreated mother to her baby during childbirth, resulting in ophthalmia neonatorum (conjunctivitis) or pneumonia in some exposed infants. In published prospective studies, chlamydial conjunctivitis has been identified in 18-44% and chlamydial pneumonia in 3-16% of infants born to women with untreated chlamydial cervical infection at the time of delivery 16. While rectal or genital chlamydial infection has been shown to persist one year or longer in infants infected at birth 17, the possibility of sexual abuse should be considered in prepubertal children beyond the neonatal period with vaginal, urethral, or rectal chlamydial infection.

People who have had chlamydia and have been treated may get infected again if they have sexual contact with a person infected with chlamydia 18.

Any sexually active person can be infected with chlamydia. It is a very common STD, especially among young people 9. It is estimated that 1 in 20 sexually active young women aged 14-24 years has chlamydia 12.

Sexually active young people are at high risk of acquiring chlamydia for a combination of behavioral, biological, and cultural reasons. Some young people don’t use condoms consistently 19. Some adolescents may move from one monogamous relationship to the next more rapidly than the likely infectivity period of chlamydia, thus increasing risk of transmission 20. Teenage girls and young women may have cervical ectopy (where cells from the endocervix are present on the ectocervix) 21. Cervical ectopy may increase susceptibility to chlamydial infection. The higher prevalence of chlamydia among young people also may reflect multiple barriers to accessing STD prevention services, such as lack of transportation, cost, and perceived stigma.

Men who have sex with men are also at risk for chlamydial infection since chlamydia can be transmitted by oral or anal sex. Among men who have sex with men screened for rectal chlamydial infection, positivity has ranged from 3.0% to 10.5% 13. Among men who have sex with men screened for pharyngeal chlamydial infection, positivity has ranged from 0.5% to 2.3% 14.

Chlamydia trachomatis infection prevention

You can get chlamydia by having vaginal, anal, or oral sex with someone who has chlamydia. Also, you can still get chlamydia even if your sex partner does not ejaculate (cum). And the only way to completely avoid chlamydia infection or other STDs is to not have vaginal, anal, or oral sex. Short of that, you can:

- Use condoms. Use a male latex condom or a female polyurethane condom during each sexual contact. Condoms used properly during every sexual encounter reduce but don’t eliminate the risk of infection.

- Limit your number of sex partners. Having multiple sex partners puts you at a high risk of contracting chlamydia and other sexually transmitted infections.

- Get regular STD tests. If you’re sexually active, particularly if you have multiple partners, talk with your doctor about how often you should be screened for chlamydia and other sexually transmitted infections.

- Avoid douching. Douching decreases the number of good bacteria in the vagina, which can increase the risk of infection.

You should always use condoms when having sex, including oral and anal sex. Latex condoms greatly reduces, but does not completely eliminate, the risk of catching or spreading STDs

If your or your partner is allergic to latex, you can use polyurethane condoms.

How to use male condoms

- Put the condom on before any contact is made.

- Unroll the condom over an erect penis to the base of the penis. (Uncircumcised men should pull back their foreskin before unrolling.) The unrolled ring should be on the outside. Leave about 1/2 inch of space in the tip so semen can collect there. Squeeze the tip to get the air out.

- Pull out after ejaculating and before the penis gets soft. To pull out, hold the rim of the condom at the base of the penis to make sure it doesn’t slip off.

- Don’t reuse condoms.

How to use female condoms

- Follow the directions on the condom package for correct placement. Be sure the inner ring goes as far into the vagina as it can. The outer ring stays outside the vagina.

- Guide the penis into the condom.

- After sex, remove the condom before standing up by gently pulling it out.

- Don’t reuse condoms.

Screening for genitourinary Chlamydia trachomatis infection

Currently, the U.S. Preventive Services Task Force recommends routine screening in all sexually active women 24 years and younger, and in women 25 years and older who are at increased risk because of having multiple partners or a new sex partner 22. Because of the high risk of intrauterine and postnatal complications if left untreated, all pregnant women at increased risk should be routinely screened for chlamydia during the first prenatal visit 6. Additionally, any pregnant woman undergoing termination of pregnancy should be tested for chlamydia infection 23.

There is insufficient evidence to recommend screening in men, although a small number of studies suggest that screening high-risk groups may be useful and cost-effective 22. Per the CDC, the screening of sexually active young men should be considered in clinical settings with a high prevalence of chlamydia (e.g., adolescent clinics, correctional facilities, sexually transmitted disease clinics), and in certain groups (e.g., men who have sex with men). In men who have sex with men, some experts recommend screening for rectal infections (a rectal swab in those who have had receptive anal intercourse during the preceding year) 6. The CDC includes chlamydia screening with a urine test among the list of annual tests for all men who have had insertive intercourse within the previous 12 months 6. Testing for Chlamydia trachomatis pharyngeal infection is not recommended in men who have had receptive oral intercourse.

Chlamydia trachomatis symptoms

Chlamydia is known as a ‘silent’ infection because most infected people are asymptomatic and lack abnormal physical examination findings. So you may not realize that you have chlamydia. But even if you don’t have symptoms, you can still pass chlamydia infection to others.

Early-stage chlamydia infections often cause few or no signs and symptoms. Even when you have signs and symptoms, they’re often mild, making them easy to overlook.

If you do have symptoms, they may not appear until 1 to 3 weeks after you have sex with someone who has chlamydia.

Signs and symptoms of chlamydia trachomatis infection can include 24, 25, 26, 27, 28, 29:

- Painful urination (a burning sensation).

- Vaginal discharge in women

- Discharge from the penis in men

- Pain in the testicles in men.

- Painful sexual intercourse in women

- Irregular periods, bleeding between periods and after sex in women

- Testicular pain in men

- Lower abdominal pain

- Rectal pain, discharge, and bleeding for men and women who engage in anal sexual activity.

- Reactive arthritis in both men and women (pain and inflammation of the joints that develops from an infection).

- Lymphogranuloma venereum. Lymphogranuloma venereum causes painful and swollen lymph nodes (buboes), which can then break down into large ulcers. Lymphogranuloma venereum symptoms include:

- Drainage through the skin from lymph nodes in the groin

- Painful bowel movements

- Small painless sore on the male genitals or in the female genital tract

- Swelling and redness of the skin in the groin area

- Swelling of the labia (in women)

- Swollen groin lymph nodes on one or both sides; it may also affect lymph nodes around the rectum in people who have anal intercourse

- Blood or pus from the rectum (blood in the stools)

Chlamydia can infect the rectum in men and women, either directly through receptive anal sex, or possibly via spread from the cervix and vagina in a woman with cervical chlamydial infection 30. Chlamydia infection of the rectum in men or women, can present with either with no signs or symptoms or with of proctitis (e.g., rectal pain, discharge, and/or bleeding) 30. You also can get chlamydial eye infections (conjunctivitis) through contact with infected body fluids.

Lymphogranuloma venereum is caused by Chlamydia trachomatis serovars L1, L2, or L3; it is an uncommon infection in the United States, but sporadic cases and outbreaks have been reported among men who have sex with men (MSM), many of whom have HIV 31, 32. Rectal manifestations with lymphogranuloma venereum can include anorectal pain, purulent rectal discharge, rectal bleeding, tenesmus, diarrhea, and constipation, which is clinically diagnosed as proctitis 31, 32. Although most cases of lymphogranuloma venereum in the United States are rectal infections, lymphogranuloma venereum can also cause enlarged inguinal lymph nodes (lymphadenopathy) characterized by multiple, unilateral, enlarged, matted, tender inguinal lymph nodes, termed “buboes” that may suppurate 31, 32. Systemic signs and symptoms, such as fever, chills, or muscle ache (myalgia), also may be present with either rectal or inguinal manifestations 33. A self-limited genital ulcer sometimes occurs at the site of inoculation. Less often, oral ulceration can occur and may be associated with cervical adenopathy. Specimens from anogenital sites and lymph nodes can be obtained in an attempt to identify Chlamydia trachomatis by a nucleic acid amplification test (NAAT).

Sexually acquired chlamydial conjunctivitis can occur in both men and women through contact with infected genital secretions 34.

While chlamydia can also be found in the throats of women and men having oral sex with an infected partner, it is typically asymptomatic and not thought to be an important cause of pharyngitis 35.

At its worst, chlamydia can damage a woman’s fertility, making it difficult to get pregnant. Also, it can cause an ectopic pregnancy (pregnancy that develops outside the womb). An extremely serious ectopic pregnancy can lead to a woman’s death.

Estimates of the proportion of chlamydia-infected people who develop symptoms vary by setting and study methodology; two published studies that incorporated modeling techniques to address limitations of point prevalence surveys estimated that only about 10% of men and 5-30% of women with laboratory-confirmed chlamydial infection develop symptoms 36. The incubation period of chlamydia is poorly defined. However, given the relatively slow replication cycle of the organism, symptoms may not appear until several weeks after exposure in those persons who develop symptoms.

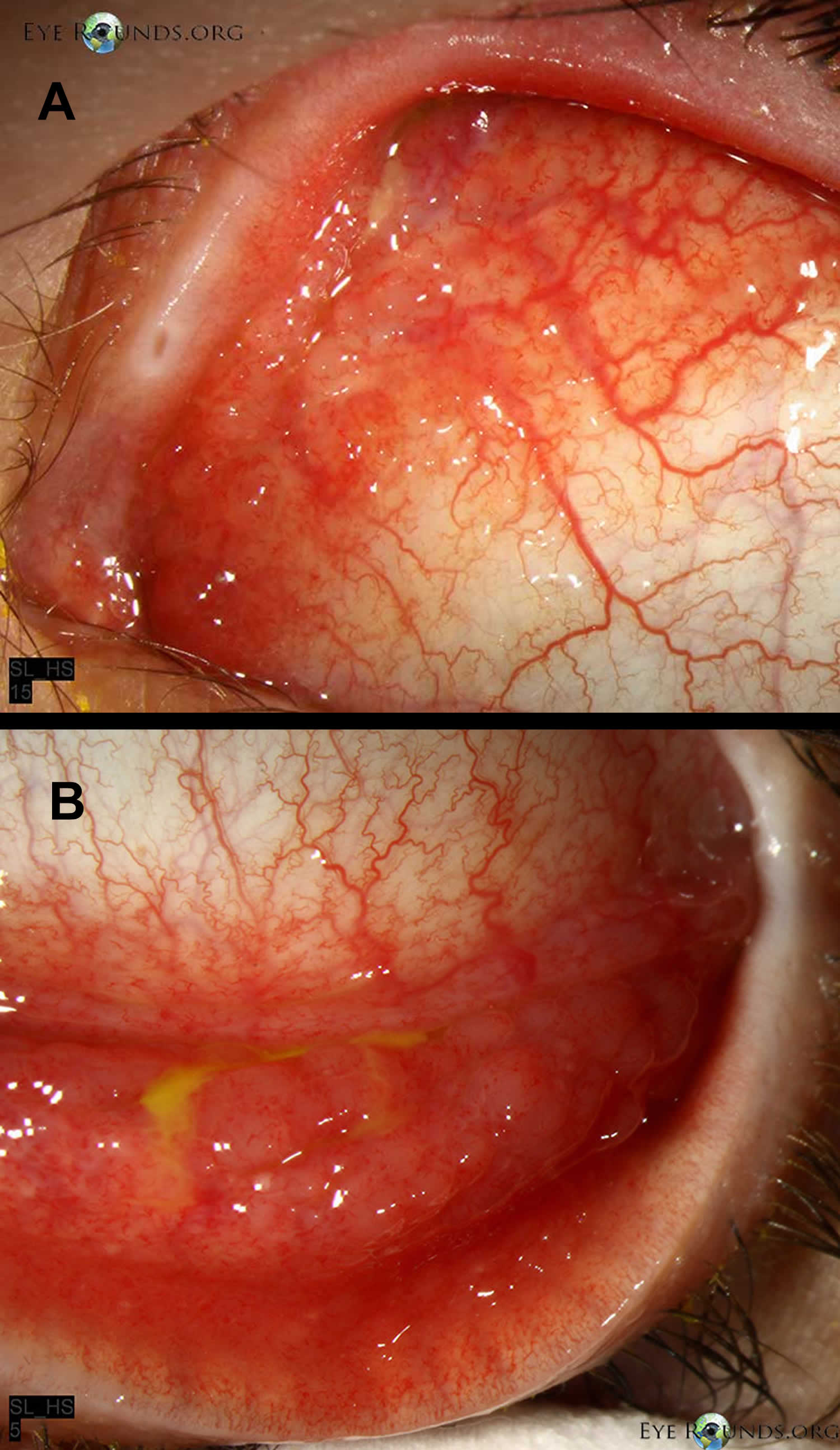

Figure 2. Chlamydia infection in eye

Footnote: (A) Follicles on the bulbar conjunctiva, characteristic of Chlamydia trachomatis infection. (B) Note the follicles in the inferior fornix

[Source 37 ]Chlamydia in women

Most women with urogenital chlamydia infection initially have no signs or symptoms, but may present later with a range of manifestations and complications. In women, the Chlamydia trachomatis bacteria initially infect the cervix, where the infection may cause signs and symptoms of cervicitis (e.g., mucopurulent endocervical discharge, easily induced endocervical bleeding), and sometimes the urethra, which may result in signs and symptoms of urethritis (e.g., pyuria, dysuria, urinary frequency). Infection can spread from the cervix to the upper reproductive tract (i.e., uterus, fallopian tubes), causing pelvic inflammatory disease (PID), which may be asymptomatic (“subclinical PID”) or acute, with typical symptoms of abdominal and/or pelvic pain, along with signs of cervical motion tenderness, and uterine or adnexal tenderness on examination 24, 25, 38.

Chlamydia symptoms in women include:

- Abnormal vaginal discharge, which may have a strong smell

- A burning sensation when urinating

If the infection spreads, you might get lower abdominal (belly) pain, pain during sex, nausea, and fever.

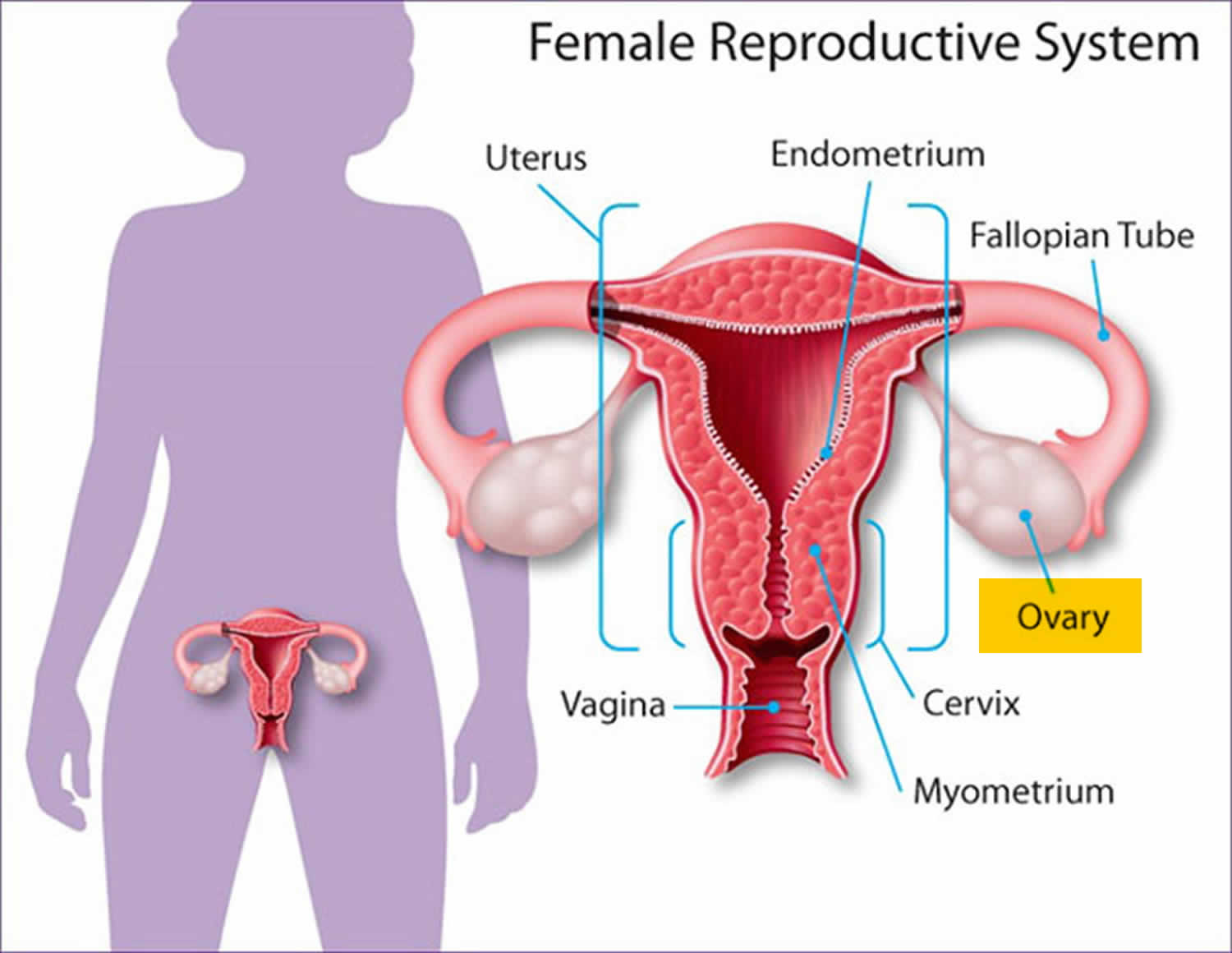

Figure 3. Female reproductive system

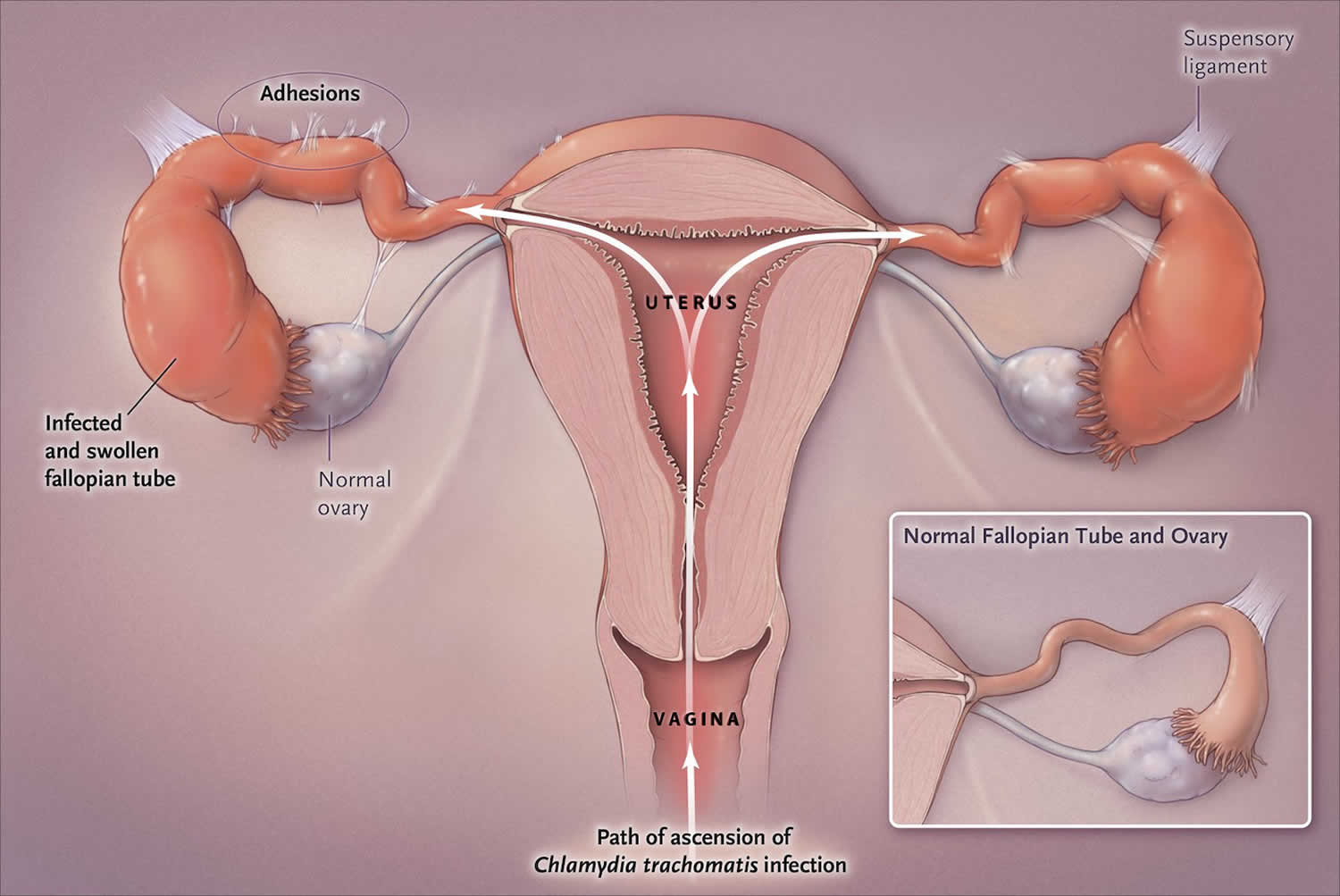

Figure 4. Chlamydia infection in the upper genital tract in women

[Source 25 ]Cervicitis

The cervix is the site of infection in 75 to 80% of women with chlamydial infection and most women with cervical chlamydial infection are asymptomatic. When symptoms are present, they are often nonspecific, such as vague abdominal discomfort or spotting. Typically, the clinical examination of the cervix is normal in women with cervical chlamydial infection, but some may have findings that suggest cervicitis, such as mucopurulent endocervical discharge and spontaneous (or easily induced) endocervical bleeding 26, 39. Causes of mucopurulent cervicitis other than Chlamydia trachomatis include Neisseria gonorrhoeae and Mycoplasma genitalium.

Urethritis

Urethral infection with chlamydia in women is usually asymptomatic, but it may cause painful urination (dysuria) and urinary frequency, which can mimic acute cystitis.[24] Nearly all women with urethral chlamydial infection also have cervical infection 40.

Pelvic inflammatory disease (PID)

Women with Chlamydia trachomatis infection can develop pelvic inflammatory disease (PID), which is a subclinical to acute clinical syndrome caused by the ascending spread of microorganisms from the cervix to the endometrium, fallopian tubes, ovaries, and contiguous structures (Figure 3) 25. Following untreated genital infection with Chlamydia trachomatis, pelvic inflammatory disease (PID) develops in approximately 3% of women within 2 weeks and in 10% of women within 1 year 41, 42. Although most women with PID caused by Chlamydia trachomatis initially have a mild or subclinical illness, some present with lower abdominal pain and may have findings of cervical motion tenderness, with or without uterine or ovary tenderness 27, 43. Chlamydia-associated pelvic inflammatory disease (PID) can result in fallopian tube scarring, which may lead to tubal factor infertility, increased risk for ectopic pregnancy, and chronic pelvic pain 25, 29. Among women treated for PID caused by chlamydia, approximately 20% become infertile, 30% develop chronic pain, and 1% have an ectopic pregnancy when they conceive 28. The extensive long-term morbidity associated with chlamydial infection underscores the importance of aggressive prevention, screening, and treatment programs 44.

Perihepatitis (Fitz-Hugh-Curtis Syndrome)

Untreated pelvic infection in women with Chlamydia trachomatis can infrequently cause inflammation of the liver capsule, which is commonly referred to as perihepatitis or the Fitz-Hugh-Curtis syndrome 45, 46. Although perihepatitis was initially attributed only to gonococcal infection, it is now known to be more often associated with chlamydial infection. Perihepatitis is characterized by right upper quadrant pain, nausea, vomiting, and fever, which are generally accompanied by evidence of pelvic inflammatory disease (PID) on physical examination 47.

Chlamydia in men

Men who are symptomatic typically have urethritis, with a mucoid or watery urethral discharge and painful urination (dysuria). A minority of infected men develop epididymitis (with or without symptomatic urethritis), presenting with unilateral testicular pain, tenderness, and swelling 48.

Chlamydia symptoms in men include:

- Discharge from your penis

- A burning sensation when urinating (peeing)

- Pain and swelling in one or both testicles (although this is less common)

If the chlamydia infects your rectum (in men or women), it can cause rectal pain, discharge, and bleeding.

Urethritis

The most common site for chlamydial infection in heterosexual men is the urethra. Although most men identified with urethral chlamydial infection have no symptoms, some will develop dysuria and urethral discharge, which is typically clear, mucoid, or mucopurulent; the clinical presentation is typically referred to as nongonococcal urethritis 49. Although attempts to distinguish gonococcal urethritis from nongonococcal urethritis on clinical examination are not reliable, the discharge caused by Chlamydia trachomatis is usually less purulent than with gonococcal urethritis.

Epididymitis

In males, epididymitis is the most common local complication of urethral Chlamydia trachomatis infection, and men with this complication typically develop unilateral scrotal pain, epididymal swelling, and tenderness 50. For men with epididymitis who have concomitant urethral discharge, most have at least 2 white blood cells per high power field on Gram’s staining of a urethral discharge specimen. Approximately 70% of sexually transmitted cases of epididymitis are due to Chlamydia trachomatis 50.

Chlamydia infections in infants and children

Although chlamydial infections are now seen infrequently among infants and children in the United States, they are still found in the cases of inadequate prenatal care. Among cases of perinatal chlamydial infection, the most common presentation is inclusion conjunctivitis, which occurs in about 25% of neonates born to mothers who have untreated cervical chlamydia infection. The second most common manifestation is neonatal pneumonia, and this occurs in only about 10 to 15% of infants of mothers who have untreated cervical chlamydia.

Conjunctivitis

For infants, conjunctivitis is the most common clinical condition resulting from perinatal transmission of chlamydia. Ocular infection with Chlamydia trachomatis results from exposure of the neonate to infected secretions from the mother’s genital tract during birth, and the exposure may also involve mucous membranes of the oropharynx, urogenital tract, and rectum. Inclusion conjunctivitis occurs 5 to 14 days after delivery. The signs range from mild scant mucoid discharge to severe copious purulent discharge, chemosis, pseudomembrane formation, erythema, friability, and edema. Neonatal ocular prophylaxis with silver nitrate solution or antibiotic ointments for prevention of gonorrhea transmission does not prevent perinatal transmission of Chlamydia trachomatis from mother to infant. A chlamydial etiology should be considered for all infants aged 30 days or younger who have conjunctivitis.

Pneumonia

Chlamydial pneumonia in infants occurs 4 to 12 weeks after delivery. Notably, infection of the nasopharynx is thought to be a precursor condition that is usually asymptomatic, but can progress to pneumonia. The signs are cough, congestion, and tachypnea. Infants are usually afebrile, and rales are apparent with auscultation of the lungs.

Trachoma

Trachoma is the most common infectious cause of blindness in the world caused by recurrent ocular surface infection and secondary scarring by Chlamydia trachomatis 51. Repeat infection with Chlamydia trachomatis leads to conjunctival inflammation and scarring, trichiasis, and ultimately blinding corneal opacification and thus a leading cause of preventible blindness. Trachoma is the leading cause of preventable blindness in the world and is caused primarily by Chlamydia trachomatis serotypes A, B, Ba, and C 52. Trachoma is found in select regions of the world, mostly in the Middle East and Southeast Asia. The disease is most often contracted person-to-person through hand (or fomite) contact with an infected eye, followed by autoinoculation. Most cases of trachoma occur in the setting of poor sanitary conditions and some cases result from fly transmission 53. The process begins as follicular conjunctivitis, which, if untreated, progresses to an entropion wherein the eyelid turns inward and chronic eyelash abrasion results in opacification of the corneal surface over time. Trachoma is diagnosed clinically and treatment with single-dose azithromycin is usually effective. Trachoma is not an STD, and it is not transmitted from mother-to-child during birth.

Urogenital infection

Urogenital infections in preadolescent males and females are usually asymptomatic and can be the result of vertical transmission during the perinatal period 24. Genital or rectal infection can persist for as long as 2 to 3 years, so infection in young children may be the result of perinatally-acquired infection. Sexual abuse is a major concern when chlamydia (or any STD) is detected in preadolescent males or females. STD evaluation in a case of suspected abuse should be performed by, or in consultation with, an expert in the assessment of child sexual abuse. Only tests with high specificity should be used because of the legal and psychosocial consequences of a false-positive diagnosis.

Chlamydia trachomatis complications

Chlamydia infection can be associated with:

- Pelvic inflammatory disease (PID). PID is an infection of the uterus and fallopian tubes that causes pelvic pain and fever. Severe infections might require hospitalization for intravenous antibiotics. PID can damage the fallopian tubes, ovaries and uterus, including the cervix.

- Infection of the epididymis (the tube that carries sperm) also known as epididymitis. A chlamydia infection can inflame the coiled tube located beside each testicle (epididymis). The infection can result in fever, scrotal pain and swelling.

- Prostate gland infection (prostatitis). Rarely, the chlamydia organism can spread to a man’s prostate gland. Prostatitis can cause pain during or after sex, fever and chills, painful urination, and lower back pain.

- Infections in newborns. The chlamydia infection can pass from the vaginal canal to your child during delivery, causing pneumonia or a serious eye infection (conjunctivitis).

- Ectopic pregnancy. This occurs when a fertilized egg implants and grows outside of the uterus, usually in a fallopian tube. The pregnancy needs to be removed to prevent life-threatening complications, such as a burst tube. A chlamydia infection increases this risk.

- Infertility. Chlamydia infections — even those that produce no signs or symptoms — can cause scarring and obstruction in the fallopian tubes, which might make women infertile.

- Reactive arthritis also known as Reiter’s syndrome. People who have Chlamydia trachomatis are at higher risk of developing reactive arthritis. This condition typically affects the joints, eyes and urethra — the tube that carries urine from your bladder to outside of your body.

In women, an untreated chlamydia infection can spread to your uterus (womb) and fallopian tubes, causing pelvic inflammatory disease (PID). PID can cause permanent damage to your reproductive system. This can lead to long-term pelvic pain, infertility, and ectopic pregnancy. Women who have had chlamydia infections more than once are at higher risk of serious reproductive health complications. Symptomatic PID occurs in about 10 to 15 percent of women with untreated chlamydia 54. However, chlamydia can also cause subclinical inflammation of the upper genital tract (“subclinical PID”). Both acute and subclinical PID can cause permanent damage to the fallopian tubes, uterus, and surrounding tissues. The damage can lead to chronic pelvic pain, tubal factor infertility, and potentially fatal ectopic pregnancy 55.

Some women with chlamydial PID develop perihepatitis, or “Fitz-Hugh-Curtis Syndrome”, an inflammation of the liver capsule and surrounding peritoneum, which is associated with right upper quadrant pain.

Men often don’t have health problems from chlamydia. Sometimes it can infect the epididymis (the tube that carries sperm) causing epididymitis. This can cause pain, fever, and, rarely, infertility 56.

Both men and women can develop reactive arthritis because of a chlamydia infection. Reactive arthritis is a type of arthritis that happens as a “reaction” to an infection in the body.

Babies born to infected mothers can get chlamydia eye infection (conjunctivitis or ophthalmia neonatorum) and pneumonia from chlamydia 15. It may also make it more likely for your baby to be born too early (premature birth or pre-term delivery) 57.

Untreated chlamydia may also increase your chances of getting or giving HIV – the virus that causes AIDS 58, 59. For men and women who are already co-infected with HIV, a concurrent chlamydia infection may increase shedding of the virus 56. Some studies have also documented an association between co-infection, human papillomavirus, and the subsequent development of cervical cancer, although the association is not definitive 60.

Reactive arthritis can occur in men and women following symptomatic or asymptomatic chlamydial infection, sometimes as part of a triad of symptoms (with urethritis and conjunctivitis) formerly referred to as Reiter’s Syndrome 61. Chlamydia-induced reactive arthritis is believed to be underdiagnosed, and emerging data suggest that asymptomatic chlamydia infections may be a common cause 62. Studies suggest that prolonged antimicrobial therapy, up to six months of combination antibiotics, may be effective 63.

Chlamydia trachomatis infection in pregnancy

In pregnant women, untreated chlamydia has been associated with pre-term delivery 57, as well as ophthalmia neonatorum (conjunctivitis) and pneumonia in the newborn. In published prospective studies, chlamydial conjunctivitis has been identified in 18-44% and chlamydial pneumonia in 3-16% of infants born to women with untreated chlamydial cervical infection at the time of delivery 64. Neonatal prophylaxis against gonococcal conjunctivitis routinely performed at birth does not effectively prevent chlamydial conjunctivitis 65.

Screening and treatment of chlamydia in pregnant women is the best method for preventing neonatal chlamydial disease. All pregnant women should be screened for chlamydia at their first prenatal visit. Pregnant women under 25 and those at increased risk for chlamydia (e.g., women who have a new or more than one sex partner) should be screened again in their third trimester. Pregnant women with chlamydial infection should be retested 3 weeks and 3 months after completion of recommended therapy 66.

Chlamydia trachomatis Pulmonary Infection

C. trachomatis is thought to cause about 12,000 cases of neonatal pneumonia per year in the United States.34,35 Fewer than 10 percent of neonates born to women with active chlamydia infection during labor develop chlamydia pneumonia.34,35 C. trachomatis pneumonia usually manifests one to three months following birth, and should be suspected in a child who has tachypnea and a staccato cough (short bursts of cough) without a fever. Chest radiography may reveal hyperinflation and bilateral diffuse infiltrates, and blood work frequently reveals eosinophilia (400 or more cells per mm3).19 In addition, specimens should be collected from the nasopharynx. For neonates who have a lung infection, erythromycin (base or ethylsuccinate, 50 mg per kg daily divided into four doses for 14 days) is the treatment of choice. Follow-up is recommended, and a second course of antibiotics may be required.19

Chlamydia trachomatis Ocular Infection

Ocular C. trachomatis infection occurs in three distinct disease patterns: ophthalmia neonatorum/neonatal conjunctivitis, adult inclusion conjunctivitis, and trachoma. Physicians treating immigrant and refugee populations, or those practicing internationally, may encounter chronic trachoma cases and should be familiar with its presentation and management.

Ophthalmia neonatorum/neonatal conjunctivitis

This infection is transmitted vaginally from an infected mother, and can present within the first 15 days of life. One-third of neonates exposed to the pathogen during delivery may be affected 67. Symptoms include conjunctival injection, various degrees of ocular discharge, and swollen eyelids. The diagnostic standard is to culture a conjunctival swab from an everted eyelid, using a Dacron swab or another swab specified for this culture. The culture must contain epithelial cells; exudates are not sufficient 67.

The recommended treatment is oral erythromycin base or ethylsuccinate (50 mg per kg daily in four divided doses for 14 days) 67. Prophylaxis with silver nitrate solution or antibiotic ointments does not prevent vertical perinatal transmission of Chlamydia trachomatis, but it will prevent ocular gonococcal infection and should therefore be administered 6.

Adult inclusion conjunctivitis

This acute mucopurulent conjunctival infection is associated with concomitant genitourinary tract chlamydia infection. If the diagnosis is suspected, a specimen from an everted lid collected using a Dacron swab should be sent for culture. Special culture media are required. Treatment consists of doxycycline (100 mg twice daily for one to three weeks) or erythromycin (250 mg four times daily for one to three weeks) 68. According to one study, a single 1-g dose of azithromycin may be just as effective 69.

Trachoma

Trachoma is a chronic or recurrent ocular infection that leads to scarring of the eyelids. This scarring often inverts the eyelids, causing abnormal positioning of the eyelashes that can scratch and damage the bulbar conjunctiva. Trachoma is the primary source of infectious blindness in the world, affecting primarily the rural poor in Asia and Africa 70. The initial infection is usually contracted outside of the neonatal period. It is easily spread via direct contact, poor hygiene, and flies. Although it has been eradicated in the United States, physicians may encounter cases in immigrants from endemic areas or during global health work.

Treatment has focused primarily on antibiotics. Although the World Health Organization has instituted its SAFE (surgery, antibiotics, facial cleanliness, and environmental improvement) program, the large heterogeneity of studies has not clearly identified which of these modalities are most effective at stemming the disease 71. Topical treatment is not effective. Mass community treatment, in which all members of a community receive antibiotics, has been found to be effective for up to two years following treatment, but recurrence and scarring remain problematic 72.

Chlamydia trachomatis diagnosis

Laboratory tests can diagnose chlamydia 73. Your doctor may ask you to provide a urine sample for testing, or they might use a cotton swab to get a vaginal sample. For women, your doctor will swab (with a long cotton swab) the inside of the vagina. For men, your doctor will swab the inside of the end of the penis. A urine test also may be required. This involves peeing in a cup provided by the doctor’s office. The urine sample is sent to a lab to be tested. If you are pregnant, your doctor may check you for chlamydia even if you have no signs of the disease. Chlamydia can be extremely dangerous to a newborn.

The Centers for Disease Control and Prevention (CDC) recommends chlamydia screening for:

- Sexually active women age 25 or younger. The rate of chlamydia infection is highest in this group, so a yearly screening test is recommended. Even if you’ve been tested in the past year, get tested when you have a new sex partner.

- Pregnant women. You should be tested for chlamydia during your first prenatal exam. If you have a high risk of infection — from changing sex partners or because your regular partner might be infected — get tested again later in your pregnancy.

- Women and men at high risk. People who have multiple sex partners, who don’t always use a condom or men who have sex with men should consider frequent chlamydia screening. Other markers of high risk are current infection with another sexually transmitted infection and possible exposure to an STD through an infected partner.

Screening and diagnosis of chlamydia is relatively simple. Tests include:

- A urine test. A sample of your urine is analyzed in the laboratory for presence of this infection.

- A swab. For women, your doctor takes a swab of the discharge from your cervix for culture or antigen testing for chlamydia. This can be done during a routine Pap test. Some women prefer to swab their vaginas themselves, which has been shown to be as diagnostic as doctor-obtained swabs.

- For men, your doctor inserts a slim swab into the end of your penis to get a sample from the urethra. In some cases, your doctor will swab the anus.

If you’ve been treated for an initial chlamydia infection, you should be retested in about three months.

Because chlamydia is usually asymptomatic, screening is necessary to identify most infections. Screening programs have been demonstrated to reduce rates of adverse sequelae in women 55. CDC recommends yearly chlamydia screening of all sexually active women younger than 25, as well as older women with risk factors such as new or multiple partners, or a sex partner who has a sexually transmitted infection 66. Pregnant women should be screened during their first prenatal care visit. Pregnant women under 25 or at increased risk for chlamydia (e.g., women who have a new or more than one sex partner) should be screened again in their third trimester 66. Women diagnosed with chlamydial infection should be retested approximately 3 months after treatment 66. Any woman who is sexually active should discuss her risk factors with a health care provider who can then determine if more frequent screening is necessary.

Routine screening is not recommended for men. However, the screening of sexually active young men should be considered in clinical settings with a high prevalence of chlamydia (e.g., adolescent clinics, correctional facilities, and STD clinics) when resources permit and do not hinder screening efforts in women 66.

Sexually active men who have sex with men who had insertive intercourse should be screened for urethral chlamydial infection and men who have sex with men who had receptive anal intercourse should be screened for rectal infection at least annually; screening for pharyngeal infection is not recommended.. More frequent chlamydia screening at 3-month intervals is indicated for men who have sex with men, including those with HIV infection, if risk behaviors persist or if they or their sexual partners have multiple partners 66.

At the initial HIV care visit, doctors should test all sexually active persons with HIV infection for chlamydia and perform testing at least annually during the course of HIV care. A patient’s health care provider might determine more frequent screening is necessary, based on the patient’s risk factors.

Chlamydia test

There are a number of diagnostic tests for chlamydia, including nucleic acid amplification tests (NAATs), cell culture, and others. Nucleic acid amplification tests (NAATs) are the most sensitive tests, and can be performed on easily obtainable specimens such as vaginal swabs (either clinician- or patient-collected) or urine 74.

Vaginal swabs, either patient- or clinician-collected, are the optimal specimen to screen for genital chlamydia using NAATs in women; urine is the specimen of choice for men, and is an effective alternative specimen type for women 74. Self-collected vaginal swab specimens perform at least as well as other approved specimens using NAATs 75. In addition, patients may prefer self-collected vaginal swabs or urine-based screening to the more invasive endocervical or urethral swab specimens 76. Adolescent girls may be particularly good candidates for self-collected vaginal swab- or urine-based screening because pelvic exams are not indicated if they are asymptomatic.

Chlamydial culture can be used for rectal or pharyngeal specimens, but is not widely available. Nucleic acid amplification tests (NAATs) have demonstrated improved sensitivity and specificity compared with culture for the detection of Chlamydia trachomatis at non-genital sites 77. Most tests, including NAATs, are not FDA-cleared for use with rectal or pharyngeal swab specimens; however, NAATS have demonstrated improved sensitivity and specificity compared with culture for the detection of Chlamydia trachomatis at rectal sites 77 and however, some laboratories have met regulatory requirements and have validated NAAT testing on rectal and pharyngeal swab specimens.

Nucleic Acid Amplification Test (NAAT)

Nucleic acid amplification tests (NAATs) amplify nucleic acid sequences (either DNA or RNA) that are specific for the organism being detected. Similar to other nonculture tests, nucleic acid amplification tests (NAATs) can detect replicating or nonviable organisms. Multiple commercially available NAATs are FDA-cleared as diagnostic tests for Chlamydia trachomatis on urine specimens from men and women, urethral secretions in men, and endocervical swabs in women; some tests are cleared for vaginal swabs 24. In addition, in May 2019, the United States Food and Drug Administration (FDA) cleared two NAATs for diagnostic testing of chlamydia at extragenital sites (pharynx and rectum); the two tests are the Aptima Combo 2 Assay and the Xpert CT/NG 78. For chlamydia testing in men, NAATs are highly sensitive for detecting Chlamydia trachomatis in either urethral secretions or a first-catch urine specimen, but most experts prefer using first-catch urine samples 24. For women, vaginal swabs are preferred over urine samples since they are more sensitive than urine samples 24. Several studies have shown that self-collected vaginal swabs are preferred by women and perform equal to or better than clinician-collected vaginal swabs 79, 80. In addition, in men and women, self-collected rectal swabs for NAAT have also performed well 81. Nucleic acid amplification tests do not distinguish non-lymphogranuloma venereum (non-LGV) from lymphogranuloma venereum (LGV) strains.

Point-of-Care NAAT Testing

In March 2021, the FDA approved the first point-of-care nucleic acid amplification test (NAAT) (Binx Health IO CT/NG Assay) for the diagnosis of urogenital chlamydia and gonorrhea 82. This point-of-care test can be run on vaginal swabs obtained from women or on urine samples collected from men 82. This assay can provide a result in approximately 30 minutes 82. In a cross-sectional study, investigators evaluated this point-of-care NAAT for the diagnosis of chlamydia and gonorrhea using vaginal swabs obtained from 1,523 women and urine samples collected from 922 men 83. For chlamydia, the sensitivity estimates were 96.1% in women and 92.5% in men; the specificity estimates were 99.1% for women and 99.3% for men 83. In addition, the investigators found that self-obtained vaginal swabs in women performed equivalent to clinician-collected vaginal swabs 83.

Non-amplification molecular tests

Molecular tests that do not use nucleic acid amplification encompass a variety of antigen detection and nucleic acid hybridization methods. These tests include enzyme-immunoassays (EIA), direct fluorescent antibody tests (DFA), and nucleic acid hybridization tests—a distinct non-NAAT methodology that can detect C. trachomatis-specific DNA or RNA sequences in ribosomal RNA, genomic DNA, or plasmid DNA. All have a significantly lower sensitivity (range 50% to 75%) than NAATs 84. These non-amplification tests are rarely used in clinical practice, and they are classified as not recommended by the Centers for Disease Control and Prevention (CDC) 24.

Culture

Historically, cell culture to detect Chlamydia trachomatis was the most sensitive and specific method available to detect chlamydial infection. Cell culture, however, is technically complex, expensive, difficult to standardize, and has a lower sensitivity than amplification tests. In addition, performing Chlamydia trachomatis cell culture requires collection of Chlamydia trachomatis elementary bodies from relevant anatomical site(s) and use of stringent transport requirements. Because of their excellent sensitivity and specificity, NAATs have replaced the use of culture in most clinical situations; the use of culture for Chlamydia trachomatis is primarily limited to evaluation of suspected cases of sexual abuse in children 85.

Serology

Serologic testing is rarely used in clinical practice to diagnose genital infections caused by Chlamydia trachomatis and chlamydia serologic tests do not reliably distinguish current from prior infection. Two main types of serologic tests are used for diagnosis: (1) chlamydia complement fixation test (CFT), which measures antibody against group-specific lipopolysaccharide antigen, and (2) microimmunofluorescence (MIF) 73.

Diagnosing lymphogranuloma venereum

Since routinely used NAATs for diagnosing chlamydial infections do not distinguish non-lymphogranuloma venereum (non-LGV) strains of Chlamydia trachomatis from lymphogranuloma venereum (LGV) strains, additional diagnostic methods, such as lymphogranuloma venereum-specific molecular testing with PCR genotyping, are required to make a laboratory diagnosis of lymphogranuloma venereum (LGV). These molecular tests, however, are not widely available and results do not return within a time frame that would alter clinical management 86. In addition, chlamydia serologic testing is not recommended for diagnosing lymphogranuloma venereum (LGV) 87. Therefore, the diagnosis of lymphogranuloma venereum (LGV) should be based on epidemiologic information, compatible clinical findings, and a positive Chlamydia trachomatis NAAT at the symptomatic anatomic site 87.

Chlamydia trachomatis treatment

Chlamydia can be easily cured with antibiotics. HIV-positive persons with chlamydia should receive the same treatment as those who are HIV-negative.

Recommended antibiotics for chlamydial infection among adolescents and adults 88:

- Doxycycline 100 mg orally 2 times/day for 7 days

Alternative Regimens

- Azithromycin 1 g orally in a single dose

- OR

- Levofloxacin 500 mg orally once daily for 7 days

Persons with chlamydia should abstain from sexual activity for 7 days after single dose antibiotics or until completion of a 7-day course of antibiotics, to prevent spreading the infection to partners. It is important to take all of the medication prescribed to cure chlamydia. Medication for chlamydia should not be shared with anyone. Although medication will cure the infection, it will not repair any permanent damage done by the disease. If a person’s symptoms continue for more than a few days after receiving treatment, he or she should return to a health care provider to be reevaluated.

Repeat infection with chlamydia is common 89. Women whose sex partners have not been appropriately treated are at high risk for re-infection. Having multiple chlamydial infections increases a woman’s risk of serious reproductive health complications, including pelvic inflammatory disease and ectopic pregnancy 90. Women and men with chlamydia should be retested about three months after treatment of an initial infection, regardless of whether they believe that their sex partners were successfully treated 66.

Infants infected with chlamydia may develop ophthalmia neonatorum (conjunctivitis) and/or pneumonia 91. Chlamydial infection in infants can be treated with antibiotics.

Uncomplicated genitourinary chlamydia infection should be treated with azithromycin (Zithromax; 1 g, single dose) or doxycycline (100 mg twice daily for seven days) see Table 1 below. Studies indicate that both treatments are equally effective 92. Although dual therapy to cover gonorrhea and chlamydia is recommended when patients are diagnosed with gonorrhea, additional coverage for gonorrhea is not required with the diagnosis of chlamydia alone 6.

Alternative regimens for uncomplicated chlamydia infection include erythromycin (500 mg four times daily for seven days), erythromycin ethylsuccinate (800 mg four times daily for seven days), levofloxacin (Levaquin; 500 mg once daily for seven days), or ofloxacin (Floxin; 300 mg twice daily or 600 mg once daily for seven days) 6. Erythromycin is reported to have higher occurrences of gastrointestinal adverse effects 92.

Pregnant women may be treated with azithromycin (1 g, single dose) or amoxicillin (500 mg three times daily for seven days). Alternative regimens include erythromycin (500 mg four times daily for seven days or 250 mg four times daily for 14 days) and erythromycin ethylsuccinate (800 mg four times daily for seven days or 400 mg four times daily for 14 days). Although all three medications show similar effectiveness, a recent review indicates that azithromycin may have fewer adverse effects when compared with erythromycin or amoxicillin in pregnant women 93.

Test of cure is recommended three to four weeks after completion of treatment in pregnant women only. If chlamydia is detected during the first trimester, repeat testing for reinfection should also be performed within three to six months, or in the third trimester 6. Men and nonpregnant women should be retested at three months. If this is not possible, clinicians should retest the patient to screen for reinfection when he or she next presents for medical care within 12 months after treatment 6.

Treatment of chlamydial infections during pregnancy

The recommended regimen for the treatment of chlamydial infections in pregnant women is azithromycin 1 gram orally in a single dose; amoxicillin is the alternative medication 24. Doxycycline and levofloxacin are not recommended for the treatment of chlamydial infections in pregnancy 24. Erythromycin is no longer recommended for the treatment of chlamydia during pregnancy due to gastrointestinal side effects that make adherence challenging for the mother during pregnancy. All pregnant women treated for chlamydial infection should have a test-of-cure performed 4 weeks after completing therapy and all should be retested 3 months after treatment for reinfection 24.

Adults with oropharyngeal chlamydial infections

The clinical significance of oropharyngeal Chlamydia trachomatis infection remains unclear, and routine screening for oropharyngeal Chlamydia trachomatis infection is not recommended. Nevertheless, since oropharyngeal C. trachomatis can be transmitted to genital sites of sex partners 94, 95, detection of Chlamydia trachomatis from an oropharyngeal sample warrants the same treatment as with urogenital chlamydial infection: doxycycline 100 mg orally twice daily for 7 days as the preferred regimen for nonpregnant adults and azithromycin 1 gram single dose orally preferred for pregnant persons 24.

Treatment for lymphogranuloma venereum

The recommended treatment for Chlamydia trachomatis infections caused by lymphogranuloma venereum strains is oral doxycycline 100 mg twice daily for 21 days; note this treatment is significantly longer than the 7-day treatment for non-lymphogranuloma venereum chlamydia strains 24. The alternative lymphogranuloma venereum treatment regimens include oral azithromycin 1 gram weekly for 3 weeks or oral erythromycin base 500 mg four times daily for 21 days 87. Since practical laboratory diagnostic methods are not available for making a timely diagnosis of lymphogranuloma venereum, the indication to provide lymphogranuloma venereum treatment (doxycycline 100 mg twice daily for 21 days) should be based on epidemiologic information, compatible clinical finding, and a positive Chlamydia trachomatis NAAT at the symptomatic anatomic site 87. In addition, empiric therapy for lymphogranuloma venereum is indicated for persons in whom (1) symptoms or signs of proctocolitis (e.g. bloody discharge, tenesmus, or ulceration), (2) those with severe inguinal lymphadenopathy with bubo formation, especially if the individual reports recently having a genital ulcer, and (3) persons with a genital ulcer and other causes for the genital ulcer have been excluded 87.

Management of sex partners

For persons diagnosed with urogenital chlamydial infection, all sex partners with whom they had sexual contact during the 60 days preceding the onset of symptoms or chlamydia diagnosis should be referred for evaluation, testing, and presumptive treatment of chlamydia 24. If no sex contacts have occurred in the 60 days before the diagnosis of chlamydia or onset of symptoms, then the most recent sex partner prior to that 60-day period should be evaluated and treated 24. All sex contacts should have testing for STDs as part of the evaluation process. The sex contacts should receive presumptive treatment for chlamydia without waiting for their STD test results to ensure the treatment does not depend on an additional follow-up visit. The empiric treatment for nonpregnant sex contacts is oral doxycycline 100 mg twice daily for 7 days and for pregnant contacts it is azithromycin 1 gram orally as a single dose. The purpose of performing an evaluation for the contact, even if they will receive presumptive treatment, is to perform counseling and screening for other STDs, which may require treatment. For neonates or infants diagnosed with chlamydial infection, it is important that mothers and their sex partners undergo diagnostic evaluation and receive empiric treatment for chlamydial infection.

Use of expedited partner therapy

Certain situations may arise in which sexual contacts are unable or unwilling to present for evaluation, testing, and treatment. In this scenario, there may be an option to provide expedited partner therapy (EPT)—a process whereby the patient diagnosed with chlamydia delivers treatment (or a prescription for treatment)—to the recent sex partner, without a medical provider examining the partner. This strategy has been demonstrated to decrease the rate of recurrent or persistent chlamydia infection 96, 97, 98. There are concerns regarding the use of expedited partner therapy for men who have sex with men, since, ideally, these individuals would get tested for other STDs, such as syphilis and HIV, during a clinic visit 24. The use of expedited partner therapy for men who have sex with men should therefore be performed on a shared-decision basis. Finally, expedited partner therapy is not legal in all states; the CDC maintains an updated information page (Legal Status of Expedited Partner Therapy) that identifies the legal status of expedited partner therapy in each state in the United States.

Infants born to mothers with chlamydial infection

When neonatal chlamydial infection occurs, it results from neonatal contact with a chlamydia-infected cervix during the birth process. Neonatal chlamydial infection most often manifests as conjunctivitis (ophthalmia neonatorum) that develops 5 to 12 days after birth or as a subacute, afebrile pneumonia with onset at ages 1 to 3 months. The erythromycin eye ointment that is routinely given to neonates at birth to prevent neonatal gonococcal ophthalmia neonatorum does not prevent neonatal chlamydial eye infection 24. The most effective strategy for preventing perinatal chlamydia transmission is to screen pregnant women for chlamydial infection and promptly treat those women who test positive. Prophylactic antibiotic treatment is not recommended for infants who are born to mothers at high risk for chlamydia or who have untreated chlamydia. In this situation, the recommended approach is to monitor the infant for signs and symptoms of chlamydial infection and promptly evaluate and treat any documented infection in the neonate 24.

Neonates with ophthalmia neonatorum

The recommended treatment regimen for the neonate with ophthalmia neonatorum is a 14-day course of oral erythromycin base or erythromycin ethylsuccinate 24. Data on oral azithromycin for the treatment of neonatal chlamydial infection are limited, but a small study suggested a short 3-day course of azithromycin may be effective.[93] The use of topical erythromycin alone is not effective for ophthalmia neonatorum, and it is not recommended for use in combination with oral antibiotics 24. The use of a recommended or alternative therapy has an efficacy of only approximately 80% and some infants require treatment with a second course of antibiotics. Treatment with oral erythromycin or oral azithromycin in infants during the first 6 weeks of life has been associated with an increased risk of infantile hypertrophic pyloric stenosis 99, 100. Thus, all infants with chlamydial ophthalmia neonatorum should have close follow-up to determine the treatment response and to evaluate signs and symptoms of infantile hypertrophic pyloric stenosis 99.

Infant pneumonia

For infants with pneumonia caused by Chlamydia trachomatis, the recommended treatment is a 14-day regimen of oral erythromycin base or erythromycin ethylsuccinate; the alternative regimen is a 3-day course of oral azithromycin 24. The treatment for chlamydial pneumonia in neonates often occurs empirically, based on the infant’s chest radiographic findings, the age of the infant, and the mother’s epidemiologic risk for chlamydial infection 24. In situations when presumptive therapy is used in a situation with a high degree of suspicion of chlamydial infection, and there is considerable concern that follow-up will not occur, the 3-day azithromycin alternative regimen can be used 24.

Chlamydial infections in infants and children

The treatment of infants and children with chlamydia is stratified into three groups: (1) younger than 8 years of age and weight less than 45 kg, (2) younger than 8 years of age and weight 45 kg or greater, and (3) age 8 or older 24. In infants and children who weigh less than 45 kg, the preferred treatment of chlamydial infections is a 14-day course of oral erythromycin base or oral erythromycin ethylsuccinate 24. For children younger than 8 years of age and weighing 45 kg or greater, the recommended regimen is single-dose oral azithromycin. Children older than 8 years of age should be treated with single-dose oral azithromycin or a 7-day course of oral doxycycline 24. A follow-up visit with chlamydia test-of-cure is recommended approximately 4 weeks after completion of treatment to evaluate for treatment effectiveness 24.

Chlamydia trachomatis prognosis

Antibiotic treatment has a 95% effectiveness rate for first-time chlamydia therapy 101. The prognosis is excellent with prompt initiation of treatment early and with the completion of the entire course of antibiotics. Although treatment failures with primary therapies are quite rare, chlamydia relapse may occur. Chlamydia reinfection is common and is usually related to the nontreatment of infected sexual partners or acquisition from a new partner. Death is rare but can be caused by progression to salpingitis and tubo-ovarian abscess with rupture and peritonitis. The most significant morbidity occurs with repetitive infection with chlamydia, which leads to scarring of the fallopian tubes and subsequent infertility.

References- Darville T, Hiltke TJ. Pathogenesis of genital tract disease due to Chlamydia trachomatis. J Infect Dis. 2010 Jun 15;201 Suppl 2(Suppl 2):S114-25. doi: 10.1086/652397

- William M. Geisler, Duration of Untreated, Uncomplicated Chlamydia trachomatis Genital Infection and Factors Associated with Chlamydia Resolution: A Review of Human Studies, The Journal of Infectious Diseases, Volume 201, Issue Supplement_2, June 2010, Pages S104–S113, https://doi.org/10.1086/652402

- Elwell C, Mirrashidi K, Engel J. Chlamydia cell biology and pathogenesis. Nat Rev Microbiol. 2016 Jun;14(6):385-400. doi: 10.1038/nrmicro.2016.30

- Morré SA, Rozendaal L, van Valkengoed IG, Boeke AJ, van Voorst Vader PC, Schirm J, de Blok S, van Den Hoek JA, van Doornum GJ, Meijer CJ, van Den Brule AJ. Urogenital Chlamydia trachomatis serovars in men and women with a symptomatic or asymptomatic infection: an association with clinical manifestations? J Clin Microbiol. 2000 Jun;38(6):2292-6. doi: 10.1128/JCM.38.6.2292-2296.2000

- Sexually Transmitted Disease Surveillance 2020. https://www.cdc.gov/std/statistics/2020/overview.htm#Chlamydia

- Workowski KA, Berman S; Centers for Disease Control and Prevention. Sexually transmitted diseases treatment guidelines, 2010 [published correction appears in MMWR Recomm Rep. 2011;60(1):18]. MMWR Recomm Rep. 2010;59(RR-12):1–110.

- O’Farrell N, Morison L, Moodley P, et al. Genital ulcers and concomitant complaints in men attending a sexually transmitted infections clinic: implications for sexually transmitted infections management. Sexually transmitted diseases 2008;35:545-9.

- Centers for Disease Control and Prevention. STD trends in the United States: 2010 national data for gonorrhea, chlamydia, and syphilis Snapshot sexually transmitted diseases in 2010. https://www.cdc.gov/std/stats10/tables/trends-snapshot.htm

- 2016 Sexually Transmitted Diseases Surveillance. https://www.cdc.gov/std/stats16/default.htm

- Satterwhite CL et al, Sexually transmitted infections among US women and men: prevalence and incidence estimates, 2008. STD 2013 Mar;40(30):187-93

- Centers for Disease Control and Prevention. STD trends in the United States: 2010 national data for gonorrhea, chlamydia, and syphilis. https://www.cdc.gov/std/stats10/tables/trends-table.htm

- Torrone E, Papp J, Weinstock H. Prevalence of Chlamydia trachomatis Genital Infection Among Persons Aged 14–39 Years — United States, 2007–2012. MMWR 2014;63:834-8.

- Pinsky L, Chiarilli DB, Klausner JD, et al. Rates of asymptomatic nonurethral gonorrhea and chlamydia in a population of university men who have sex with men. Journal of American college health : J of ACH 2012;60:481-4.

- Park J, Marcus JL, Pandori M, Snell A, Philip SS, Bernstein KT. Sentinel surveillance for pharyngeal chlamydia and gonorrhea among men who have sex with men–San Francisco, 2010. Sexually transmitted diseases 2012;39:482-4.

- Chlamydia – CDC Basic Fact Sheet. https://www.cdc.gov/std/chlamydia/stdfact-chlamydia.htm

- Schachter J, Grossman M, Sweet RL, Holt J, Jordan C, Bishop E. Prospective study of perinatal transmission of Chlamydia trachomatis. JAMA : the journal of the American Medical Association 1986;255:3374-7.

- Bell TA, Stamm WE, Wang SP, Kuo CC, Holmes KK, Grayston JT. Chronic Chlamydia trachomatis infections in infants. JAMA : the journal of the American Medical Association 1992;267:400-2.

- Batteiger BE, Tu W, Ofner S, et al. Repeated Chlamydia trachomatis genital infections in adolescent women. The Journal of infectious diseases 2010;201:42-51.

- Eaton DK, Kann L, Kinchen S, et al. Youth risk behavior surveillance – United States, 2011. Morbidity and mortality weekly report Surveillance summaries (Washington, DC : 2002) 2012;61:1-162.

- Kraut-Becher JR, Aral SO. Gap length: an important factor in sexually transmitted disease transmission. Sexually transmitted diseases 2003;30:221-5.

- Singer A. The uterine cervix from adolescence to the menopause. British journal of obstetrics and gynaecology 1975;82:81-99.

- U. S. Preventive Services Task Force. Screening for chlamydia infection: recommendation statement. Ann Intern Med. 2007;147(2):128–134.

- Scottish Intercollegiate Guidelines Network. Management of genital chlamydia trachomatis infection. http://www.sign.ac.uk/guidelines/fulltext/109/index.html

- Chlamydial Infections. https://www.cdc.gov/std/treatment-guidelines/chlamydia.htm

- Wiesenfeld HC. Screening for Chlamydia trachomatis Infections in Women. N Engl J Med. 2017 Feb 23;376(8):765-773. doi: 10.1056/NEJMcp1412935

- Jeanne M. Marrazzo, David H. Martin, Management of Women with Cervicitis, Clinical Infectious Diseases, Volume 44, Issue Supplement_3, April 2007, Pages S102–S110, https://doi.org/10.1086/511423

- Brunham RC, Gottlieb SL, Paavonen J. Pelvic inflammatory disease. N Engl J Med. 2015 May 21;372(21):2039-48. doi: 10.1056/NEJMra1411426

- Ness RB, Soper DE, Holley RL, Peipert J, Randall H, Sweet RL, Sondheimer SJ, Hendrix SL, Amortegui A, Trucco G, Songer T, Lave JR, Hillier SL, Bass DC, Kelsey SF. Effectiveness of inpatient and outpatient treatment strategies for women with pelvic inflammatory disease: results from the Pelvic Inflammatory Disease Evaluation and Clinical Health (PEACH) Randomized Trial. Am J Obstet Gynecol. 2002 May;186(5):929-37. doi: 10.1067/mob.2002.121625

- Brunham RC, Binns B, McDowell J, Paraskevas M. Chlamydia trachomatis infection in women with ectopic pregnancy. Obstet Gynecol. 1986 May;67(5):722-6. doi: 10.1097/00006250-198605000-00022

- Barry PM, Kent CK, Philip SS, Klausner JD. Results of a program to test women for rectal chlamydia and gonorrhea. Obstetrics and gynecology 2010;115:753-9.

- Handsfield HH. Lymphogranuloma Venereum Treatment and Terminology. Sex Transm Dis. 2018 Jun;45(6):409-411. doi: 10.1097/OLQ.0000000000000853

- Bradley P. Stoner, Stephanie E. Cohen, Lymphogranuloma Venereum 2015: Clinical Presentation, Diagnosis, and Treatment, Clinical Infectious Diseases, Volume 61, Issue suppl_8, December 2015, Pages S865–S873, https://doi.org/10.1093/cid/civ756

- Schachter J, Moncada J. Lymphogranuloma venereum: how to turn an endemic disease into an outbreak of a new disease? Start looking. Sex Transm Dis. 2005 Jun;32(6):331-2. doi: 10.1097/01.olq.0000168429.13282.c8

- Kalayoglu MV. Ocular chlamydial infections: pathogenesis and emerging treatment strategies. Current drug targets Infectious disorders 2002;2:85-91.

- Jones RB, Rabinovitch RA, Katz BP, et al. Chlamydia trachomatis in the pharynx and rectum of heterosexual patients at risk for genital infection. Annals of internal medicine 1985;102:757-62.

- Farley TA, Cohen DA, Elkins W. Asymptomatic sexually transmitted diseases: the case for screening. Preventive medicine 2003;36:502-9.

- Chlamydia Trachomatis Infection. https://webeye.ophth.uiowa.edu/eyeforum/atlas/pages/chlamydia-trachomatis-infection.htm

- Wiesenfeld HC, Sweet RL, Ness RB, Krohn MA, Amortegui AJ, Hillier SL. Comparison of acute and subclinical pelvic inflammatory disease. Sexually transmitted diseases 2005;32:400-5.

- Taylor SN. Cervicitis of unknown etiology. Curr Infect Dis Rep. 2014 Jul;16(7):409. doi: 10.1007/s11908-014-0409-x

- Bradley MG, Hobson D, Lee N, Tait IA, Rees E. Chlamydial infections of the urethra in women. Genitourin Med. 1985 Dec;61(6):371-5. doi: 10.1136/sti.61.6.371

- Hook EW, Spitters C, Reichart CA, Neumann TM, Quinn TC. Use of Cell Culture and a Rapid Diagnostic Assay for Chlamydia trachomatis Screening. JAMA. 1994;272(11):867–870. doi:10.1001/jama.1994.03520110047027

- Oakeshott P, Kerry S, Aghaizu A, Atherton H, Hay S, Taylor-Robinson D, Simms I, Hay P. Randomised controlled trial of screening for Chlamydia trachomatis to prevent pelvic inflammatory disease: the POPI (prevention of pelvic infection) trial. BMJ. 2010 Apr 8;340:c1642. doi: 10.1136/bmj.c1642

- Ross JD. Pelvic inflammatory disease. BMJ Clin Evid. 2013 Dec 11;2013:1606

- LeFevre ML; U.S. Preventive Services Task Force. Screening for Chlamydia and gonorrhea: U.S. Preventive Services Task Force recommendation statement. Ann Intern Med. 2014 Dec 16;161(12):902-10. doi: 10.7326/M14-1981

- Money DM, Hawes SE, Eschenbach DA, Peeling RW, Brunham R, Wölner-Hanssen P, Stamm WE. Antibodies to the chlamydial 60 kd heat-shock protein are associated with laparoscopically confirmed perihepatitis. Am J Obstet Gynecol. 1997 Apr;176(4):870-7. doi: 10.1016/s0002-9378(97)70613-6

- Wang SP, Eschenbach DA, Holmes KK, Wager G, Grayston JT. Chlamydia trachomatis infection in Fitz-Hugh-Curtis syndrome. Am J Obstet Gynecol. 1980 Dec 1;138(7 Pt 2):1034-8. doi: 10.1016/0002-9378(80)91103-5

- Ris HW. Perihepatitis (Fitz-Hugh–Curtis syndrome). A review and case presentation. J Adolesc Health Care. 1984 Oct;5(4):272-6. doi: 10.1016/s0197-0070(84)80131-x

- Berger RE, Alexander ER, Monda GD, Ansell J, McCormick G, Holmes KK. Chlamydia trachomatis as a cause of acute “idiopathic” epididymitis. The New England journal of medicine 1978;298:301-4.

- Moi H, Blee K, Horner PJ. Management of non-gonococcal urethritis. BMC Infect Dis. 2015 Jul 29;15:294. doi: 10.1186/s12879-015-1043-4