What is cellulitis

Cellulitis is a common, potentially serious bacterial infection of the skin (the lower dermis) and subcutaneous tissues (just under the skin). The affected skin appears swollen and red (but this may be less obvious on brown or black skin) and is typically painful and warm to the touch 1, 2, 3, 4, 5, 6. The skin may look pitted, like the peel of an orange, or blisters may appear on the affected skin 7. Cellulitis is sometimes accompanied by fever, chills, and general fatigue. Cellulitis can appear anywhere on the body, but it is most common on the feet and legs 7. Cellulitis is usually caused by a bacterial infection and can become serious if not treated with antibiotics. The most common bacteria are Staphylococcus aureus (golden Staph) and group A beta-hemolytic Streptococcus (Streptococcus pyogenes). These bacteria are able to enter the skin through small cracks (fissures) or normal skin, and can spread easily to the tissue under the skin.

Cellulitis can affect almost any part of your body (e.g., face, eye, arms and other areas). Most commonly, cellulitis occurs on the lower legs and in areas where the skin is damaged or inflamed allowing bacteria to enter. Anyone, at any age, can develop cellulitis. However, you are at increased risk if you smoke, have diabetes or poor circulation.

Left untreated, cellulitis can spread to your lymph nodes (lymphadenitis) and can result in pockets of pus (abscesses) or the bacteria can spread into your bloodstream (bacteremia) and rapidly become life-threatening. Prior to the development of antibiotics, cellulitis was fatal. With the introduction of antibiotics, most people recover fully within a week.

Cellulitis isn’t usually spread from person to person.

If you think you or someone in your care has cellulitis, it’s important to get medical attention soon as possible!

The main signs of cellulitis are skin that is red, painful, swollen, tender and warm to touch. People with severe cellulitis can get fever, chills, sweating and nausea, and might feel generally unwell.

Cellulitis often affects the lower leg, but can occur on any part of the body including the face. The infection may occur when bacteria enter the skin through an ulcer, cut or a scratch or an insect bite. However it can occur without any visible damage to the skin.

Sometimes bacteria from cellulitis spreads into the blood stream, which is called sepsis and this is a medical emergency.

People with cellulitis can quickly become very unwell and a small number of people may develop serious complications.

Complications from cellulitis are uncommon but can include serious infections:

- Bacteremia (blood infection)

- Toxic shock syndrome or sepsis

- Suppurative arthritis (bacterial infection in a joint)

- Osteomyelitis (bone infection)

- Endocarditis (a life-threatening inflammation of the inner lining of the heart’s chambers and heart valves)

Cellulitis can also cause thrombophlebitis (swelling in a vein due to a blood clot).

Rarely, cellulitis can spread to the deep layer of tissue called the fascial lining. Necrotizing fasciitis is an example of a deep-layer infection. It’s an extreme emergency.

Doctors typically diagnose cellulitis by looking at the affected skin during a physical examination. Blood or other lab tests are usually not needed.

Antibiotics are the main treatment, usually orally at home. Some people need treatment in hospital with intravenous (IV) antibiotics. Rest and elevation (raising) of the limb are also very important as it can help decrease swelling and speed up recovery. In some cases the affected limb may need compression.

After successful treatment, the skin may flake or peel off as it heals. This can be itchy.

Figure 1. Cellulitis leg

Figure 2. Cellulitis foot

Figure 3. Facial cellulitis

It’s important to identify and treat cellulitis early because the condition can spread rapidly throughout your body.

Seek emergency care if:

- You have a red, swollen, tender rash or a rash that’s changing rapidly

- You have a fever

See your doctor, preferably that day, if:

- You have a rash that’s red, swollen, tender and warm — and it’s expanding — but without fever

Who gets cellulitis?

Cellulitis affects people of all ages and races. Factors that increase the risk of developing cellulitis include:

- Previous episode(s) of cellulitis

- Skin wounds or injuries that cause a break in the skin (like cuts, ulcers, bites, puncture wounds, tattoos, piercings)

- Fissuring of toes or heels, eg due to athlete’s foot, tinea pedis or cracked heels

- Poor circulation in the legs (peripheral vascular disease)

- Venous disease, eg gravitational eczema, leg ulceration, and/or lymphedema

- Having limbs (feet, legs, hands, and arms) that stay swollen (chronic edema), including swelling due to:

- Lymphedema (problems with the lymphatic system so it does not drain the way it should); the lymphatic system is a part of the body’s immune system that helps move fluid that contains infection-fighting cells throughout the body

- Coronary artery bypass grafting (having a healthy vein removed from the leg and connected to the coronary artery to improve blood flow to the heart)

- Bites from insects, animals, or other humans

- Chronic lower leg swelling (edema)

- Current or prior injury, eg trauma, surgical wounds, radiotherapy

- Immunodeficiency, eg human immunodeficiency virus infection (HIV)

- Intravenous drug abuse

- Weakened immune system due to underlying illness or medication

- Diabetes

- Chronic kidney disease

- Chronic liver disease

- Obesity

- Pregnancy

- Alcoholism

- Athlete’s foot (tinea pedis)

- Chickenpox

- Shingles

- Eczema

Many people falsely attribute an episode of cellulitis to an unseen spider bite. Documented spider bites have not led to cellulitis.

Is cellulitis contagious?

Cellulitis isn’t usually spread from person to person. Cellulitis is an infection of the deeper layers of the skin most commonly caused by bacteria that normally live on the skin’s surface. You have an increased risk of developing cellulitis if you:

- Have an injury, such as a cut, fracture, burn or scrape

- Have a skin condition, such as eczema, athlete’s foot or shingles

- Participate in contact sports, such as wrestling

- Have diabetes or a weakened immune system

- Have a chronic swelling of your arms or legs (lymphedema)

- Use intravenous drugs

However, direct person-to-person transmission of group A strep (Streptococcus pyogenes) can occur through contact with skin lesions or exposure to respiratory droplets 6. People with active infection are more likely to transmit group A strep (Streptococcus pyogenes) compared to asymptomatic carriers. Local dermatophyte (fungal) infection (e.g., athlete’s foot) may serve as portal of entry for group A strep (Streptococcus pyogenes) 1.

The spread of all types of group A strep (Streptococcus pyogenes) infection can be reduced by good hand hygiene, especially after coughing and sneezing, and respiratory etiquette (e.g., covering your cough or sneeze). Early identification and management of superficial skin lesions is also key to cellulitis prevention. Patients with recurrent cellulitis on their leg or foot should be inspected for tinea pedis and should be treated if present. Traumatic or bite wounds should be cleaned and managed appropriately (e.g., antibiotic prophylaxis, surgical debridement if indicated) to prevent secondary infections 4.

Reduce the risk of transmission

Cellulitis is spread by skin-to-skin contact or by touching infected surfaces. Stop the spread by:

- Washing your hands often.

- Bathing or showering daily.

- Do not let dressing become wet. If they do get wet they will need to be changed. Do not swim until infection clears up.

- Covering the wound with a gauze dressing (not a Band-Aid)

- Washing your bed linen, towels and clothing separately from other family members while the infection is healing.

Cellulitis may arise when skin injury or inflammation is not adequately treated.

How to clean a wound

You can look after most cuts and wounds yourself. You can:

- Stop any bleeding by holding a clean cloth or bandage on it and apply firm pressure. Use a clean towel to apply light pressure to the area until bleeding stops (this may take a few minutes). Minor cuts and scrapes usually stop bleeding on their own. Be aware that some medicines (e.g. aspirin and warfarin) will affect bleeding, and may need pressure to be applied for a longer period of time. If needed, apply gentle pressure with a clean bandage or cloth and elevate the wound until bleeding stops.

- Wash your hands well. Prior to cleaning or dressing the wound, ensure your hands are washed to prevent contamination and infection of the wound.

- Clean the wound by rinsing it with clean water and picking out any dirt (e.g. gravel) or debris with tweezers (don’t use antiseptic cream), as this will reduce the risk of infection. Keeping the wound under running tap water will reduce the risk of infection. Wash around the wound with soap.

- Dry the wound. Gently pat dry the surrounding skin with a clean pad or towel.

- Replace any skin flaps if possible. If there is a skin flap and it is still attached, gently reposition the skin flap back over the wound as much as possible using a moist cotton bud or pad.

- To help the injured skin heal, use an antibiotic ointment (e.g., Neosporin, Polysporin) or petroleum jelly to keep the wound moist. Petroleum jelly prevents the wound from drying out and forming a scab; wounds with scabs take longer to heal. This will also help prevent a scar from getting too large, deep or itchy. As long as the wound is cleaned daily, it is not necessary to use anti-bacterial ointments. However, several studies have supported the use of prophylactic topical antibiotics for minor wounds. An randomized controlled trial of 426 patients with uncomplicated wounds found significantly lower infection rates with topical bacitracin, neomycin/bacitracin/polymyxin B, or silver sulfadiazine (Silvadene) compared with topical petrolatum (5.5%, 4.5%, 12.1%, and 17.6%, respectively) 8. Certain ingredients in some ointments can cause a mild rash in some people. If a rash appears, stop using the ointment.

- Cover the wound (small wounds can be left uncovered) 9. Use a non-stick or gentle dressing and lightly bandage in place; try to avoid using tape on fragile skin to prevent further trauma on dressing removal. Dressings protect the wound by acting as a barrier to infection and absorbing wound fluid. A moist wound bed stimulates epithelial cells to migrate across the wound bed and resurface the wound 10. A dry environment leads to cell desiccation and causes scab formation, which delays wound healing. Older studies in animals and humans suggest that moist wounds had faster rates of re-epithelialization compared with dry wounds 11.

- Manage pain. Wounds can be painful, so consider pain relief while the wound heals. Talk to your doctor or pharmacist about options for pain relief.

- Change the dressing every day or whenever the bandage becomes wet or dirty.

- Get a tetanus shot. Get a tetanus shot if you haven’t had one in the past five years and the wound is deep or dirty.

- Watch for signs of infection. See a doctor if you see signs of infection on the skin or near the wound, such as redness, increasing pain, drainage, warmth or swelling.

- It’s also important to care for yourself, as this helps wounds heal faster. So eat fresh food, get some exercise, avoid smoking, and avoid drinking too much and drink plenty of water (unless you have liquid intake restrictions) to maintain supple, healthy skin.

See a doctor or nurse for a tetanus immunization within a day if you have had any cut or abrasion and any of the following apply:

- It is more than 10 years since your last tetanus shot or you can’t remember when you last had a tetanus shot 12. The Centers for Disease Control and Prevention (CDC) recommends that tetanus toxoid be administered as soon as possible to patients who have no history of tetanus immunization, who have not completed a primary series of tetanus immunization (at least three tetanus toxoid–containing vaccines), or who have not received a tetanus booster in the past 10 years.

- It is more than five years since your last tetanus shot and there was dirt in in the cut or abrasion, or the cut is deep.

- You should have the tetanus booster shot within 48 hours of the injury.

- Besides a tetanus shot, your doctor may also give you an injection of something called tetanus immune globulin, which acts fast to prevent infection 13. There is a small window of opportunity for the tetanus immune globulin to work, so don’t delay seeking medical care.

- Be aware of the first signs of tetanus infection. Also known as lockjaw, tetanus causes stiffness of the neck, difficulty swallowing, rigidity of abdominal muscles, spasms, sweating and fever. Symptoms usually begin eight days after the infection, but occur anywhere within three days to three weeks.

Cellulitis causes

Cellulitis occurs when bacteria, most commonly Streptococcus pyogenes (two thirds of cases) and Staphylococcus aureus (one third of cases), enter through a crack or break in your skin. The incidence of a more serious staphylococcus infection called methicillin-resistant Staphylococcus aureus (MRSA) is increasing.

For many people who get cellulitis, experts do not know how the bacteria get into the body. Sometimes the bacteria get into the body through openings in the skin, like an injury or surgical wound. In general, people cannot catch cellulitis from someone else; it is not contagious.

Rare causes of cellulitis include 14:

- Pseudomonas aeruginosa, usually in a puncture wound of foot or hand

- Haemophilus influenzae, in children with facial cellulitis

- Anaerobes, Eikenella, Streptococcus viridans, due to human bite

- Pasteurella multocida, due to cat or dog bite

- Vibrio vulnificus, due to salt water exposure, e.g., coral injury

- Aeromonas hydrophila from fresh or salt water exposure, e.g., following leech bites

- Erysipelothrix (erysipeloid), in butchers

Cellulitis usually occurs in skin areas that have been damaged or inflamed for other reasons, including:

- trauma, such as an insect bite, burn, abrasion or cut

- a surgical wound

- skin problems, such as eczema, psoriasis, scabies or acne

- a foreign object in the skin, such as metal or glass.

Often, it is not possible to find a cause for cellulitis.

Although cellulitis can occur anywhere on your body, the most common location is the lower leg. Bacteria are most likely to enter disrupted areas of skin, such as where you’ve had recent surgery, cuts, puncture wounds, an ulcer, athlete’s foot or dermatitis.

Animal bites can cause cellulitis. Bacteria can also enter through areas of dry, flaky skin or swollen skin.

Risk factors for developing cellulitis

Several factors put you at increased risk of cellulitis:

- Injury. Any cut, fracture, burn or scrape gives bacteria an entry point.

- Weakened immune system. Conditions that weaken your immune system — such as diabetes, leukemia and HIV/AIDS — leave you more susceptible to infections. Certain medications also can weaken your immune system.

- Skin conditions. Conditions such as eczema, athlete’s foot and shingles can cause breaks in the skin, which give bacteria an entry point.

- Chronic swelling of your arms or legs (lymphedema). This condition sometimes follows surgery.

- History of cellulitis. Having had cellulitis before makes you prone to develop it again.

- Obesity. Being overweight or obese increases your risk of developing cellulitis.

Cellulitis prevention

If your cellulitis recurs, your doctor may recommend preventive antibiotics. To help prevent cellulitis and other infections, take these precautions when you have a skin wound:

- Wash your wound daily with soap and water. Do this gently as part of your normal bathing.

- Apply a protective cream or ointment. For most surface wounds, an over-the-counter ointment (Vaseline, Polysporin, others) provides adequate protection.

- Cover your wound with a bandage. Change bandages at least daily.

- Watch for signs of infection. Redness, pain and drainage all signal possible infection and the need for medical evaluation.

People with diabetes and those with poor circulation need to take extra precautions to prevent skin injury. Good skin care measures include the following:

- Inspect your feet daily. Regularly check your feet for signs of injury so you can catch infections early.

- Moisturize your skin regularly. Lubricating your skin helps prevent cracking and peeling. Do not apply moisturizer to open sores.

- Trim your fingernails and toenails carefully. Take care not to injure the surrounding skin.

- Protect your hands and feet. Wear appropriate footwear and gloves.

- Promptly treat infections on the skin’s surface (superficial), such as athlete’s foot. Superficial skin infections can easily spread from person to person. DON’T wait to start treatment.

How to prevent recurrent episodes of cellulitis

To help prevent recurrent episodes of cellulitis — a bacterial infection in the deepest layer of skin — keep skin clean and well-moisturized. Prevent cuts and scrapes by wearing appropriate clothing and footwear, using gloves when necessary, and trimming fingernails and toenails with care.

Factors that may increase your risk of cellulitis include:

- Pre-existing skin diseases, such as athlete’s foot

- Puncture injuries, such as insect or animal bites

- Surgical incisions or pressure sores

- Immune system problem, such as diabetes

- Injuries that occur when you’re in a lake, river or ocean

- Hot tub use

Cellulitis usually makes the affected skin hot, red, swollen and painful. Your skin may look pebbled, like an orange peel. Seek prompt medical attention at the first sign of a skin infection. Treatment is usually with antibiotics. Some people who frequently develop cellulitis may benefit from long-term low-dose antibiotic treatment to prevent recurrent infections. Prophylactic antibiotics, such as oral penicillin or erythromycin oral twice daily for 4–52 weeks, or intramuscular benzathine penicillin every 2–4 weeks, should be considered in patients who have 3–4 episodes of cellulitis per year despite attempts to treat or control predisposing factors 4. This antibiotic program should be continued so long as the predisposing factors persist 4.

Cellulitis symptoms

Possible signs and symptoms of cellulitis, which usually occur on one side of the body, include:

- Redness, swelling and tenderness of skin and subcutaneous tissue underneath it that tends to expand (spread)

- Warmth of the affected skin

- Fever and chills

- Swollen glands or lymph nodes

- Pain

- Red spots

- Blisters

- Dimpled skin (peau d’orange)

- Weeping or leaking of yellow clear fluid or pus

- Erosions and ulceration

- Abscess formation

- Purpura: petechiae, ecchymoses, or hemorrhagic bullae

Cellulitis may be associated with lymphangiitis and lymphadenitis, which are due to bacteria within lymph vessels and local lymph glands. A red line tracks from the site of infection to nearby tender, swollen lymph glands.

Left untreated, cellulitis can rapidly turn into a life-threatening condition. Treatment usually includes antibiotics. In severe cases, you may need to be hospitalized and receive antibiotics through your veins (intravenously).

Cellulitis complications

The infection can spread to the rest of the body. The lymph nodes may swell and be noticed as a tender lump in the groin and armpit. You may also have fevers, sweats and vomiting.

Severe or rapidly progressive cellulitis may lead to:

- Necrotizing fasciitis (a more serious soft tissue infection recognized by severe pain, skin pallor, loss of sensation, purpura, ulceration and necrosis). Necrotizing fasciitis is an example of a deep-layer infection. It’s an extreme emergency.

- Gas gangrene

- Severe sepsis (blood poisoning)

- Infection of other organs, e.g., pneumonia, osteomyelitis, meningitis

- Endocarditis (heart valve infection).

Sepsis is recognized by fever, malaise, loss of appetite, nausea, lethargy, headache, aching muscles and joints. Serious infection leads to hypotension (low blood pressure, collapse), reduced capillary circulation, heart failure, diarrhea, gastrointestinal bleeding, renal failure and loss of consciousness.

Recurrent episodes of cellulitis may damage the lymphatic drainage system and cause chronic swelling of the affected limb.

Cellulitis diagnosis

Your doctor will likely be able to diagnose cellulitis by looking at your skin. In some cases, he or she may suggest blood tests or other tests to help rule out other conditions.

Investigations may reveal:

- Leukocytosis (raised white cell count).

- Elevated C-reactive protein (CRP)

- Causative organism, on culture of blood or of pustules, crusts, erosions or wound

Imaging may be performed. For example:

- Chest X-ray in case of heart failure or pneumonia

- Doppler ultrasound to look for blood clots (deep vein thrombosis)

- MRI in case of necrotizing fasciitis.

Cellulitis treatment

Antibiotics are used to treat the infection. Oral antibiotics may be adequate, but in the severely ill person, intravenous antibiotics will be needed to control and prevent further spread of the infection. This treatment is given in hospital or sometimes, at home by a local doctor or nurse. Your doctor also might recommend elevating the affected area, which may speed recovery.

For typical cases of non-purulent cellulitis, the Infectious Diseases Society of America (IDSA) recommends treatment with an antibiotic that is active against streptococci 4. Due to the difficulty of determining the causative pathogen for most cellulitis cases, clinicians may select antibiotics that cover both Staphylococcus aureus and group A beta-hemolytic Streptococcus (Streptococcus pyogenes).

Group A beta-hemolytic Streptococcus (Streptococcus pyogenes) remains susceptible to beta-lactam antibiotics. Mild cellulitis can be treated with oral antibiotics, including penicillin, cephalosporins (e.g., cephalexin), dicloxacillin, or clindamycin. If signs of systemic infection are present, then intravenous antibiotics can be considered, such as penicillin, ceftriaxone, cefazolin, or clindamycin 4.

The recommended duration of antibiotic treatment for most cellulitis cases is 5 days 4. Cases in which there has not been improvement during this time period may require longer durations of treatment 4.

In addition, elevation of the affected area and treating predisposing factors (e.g., edema, underlying skin disorders) is recommended to reduce the risk of recurrent infection 4.

Within three days of starting an antibiotic, let your doctor know whether the infection is responding to treatment. You’ll need to take the antibiotic for as long as your doctor directs, usually five to 10 days but possibly as long as 14 days. After successful treatment, the skin may flake or peel off as it heals. This can be itchy.

As the infection improves, you may be able to change from intravenous to oral antibiotics, which can be taken at home for a further week to 10 days. Most people respond to antibiotics in two to three days and begin to show improvement. In some cases, antibiotics are continued until all signs of infection have cleared (redness, pain and swelling), sometimes for several months.

In most cases, signs and symptoms of cellulitis disappear after a few days. You may need to be hospitalized and receive antibiotics through your veins (intravenously) if:

- Signs and symptoms don’t respond to oral antibiotics

- Signs and symptoms are extensive

- You have a high fever

In rare cases, the cellulitis may progress to a serious illness by spreading to deeper tissues. In addition to broad spectrum antibiotics, surgery is sometimes required.

Treatment should also include:

- Analgesia to reduce pain

- Adequate water/fluid intake

- Management of co-existing skin conditions like venous eczema or tinea pedis

Cellulitis antibiotics

The management of cellulitis is becoming more complicated due to rising rates of methicillin-resistant Staphylococcus aureus (MRSA) and macrolide- or erythromycin-resistant Streptococcus pyogenes.

Usually, doctors prescribe a drug that’s effective against both streptococci and staphylococci. It’s important that you take the medication as directed and finish the entire course of medication, even after you feel better.

Treatment of cellulitis with systemic illness

More severe cellulitis and systemic symptoms should be treated with fluids, intravenous antibiotics and oxygen. The choice of antibiotics depends on local protocols based on prevalent organisms and their resistance patterns, and may be altered according to culture/susceptibility reports.

- Penicillin-based antibiotics are often chosen (eg penicillin G or flucloxacillin)

- Amoxicillin and clavulanic acid provide broad-spectrum cover if unusual bacteria are suspected

- Cephalosporins are also commonly used (eg ceftriaxone, cefotaxime or cefazolin)

- Clindamycin, sulfamethoxazole/trimethoprim, doxycycline and vancomycin are used in patients with penicillin or cephalosporin allergy, or where infection with methicillin-resistant Staphylococcus aureus is suspected

- Broad-spectrum antibiotics may also include linezolid, ceftaroline, or daptomycin

Sometimes oral probenecid is added to maintain antibiotic levels in the blood.

Treatment may be switched to oral antibiotics when fever has settled, cellulitis has regressed, and CRP is reducing.

Cellulitis home treatment

Self-care at home to help ease any pain and swelling include:

- Get plenty of rest. This gives your body a chance to fight the infection.

- Raise the area of the body involved as high as possible. This will ease the pain, help drainage and reduce swelling.

- Take pain-relieving medication such as paracetamol. Check the label for how much to take and how often. The pain eases once the infection starts getting better.

- If you are not admitted to hospital, you will require a follow-up appointment with your doctor within a day or two to make sure the cellulitis is improving. This appointment is important to attend.

Management of recurrent cellulitis

Patients with recurrent cellulitis should:

- Avoid trauma, wear long sleeves and pants in high risk activities, eg gardening

- Keep skin clean and well moisturized, with nails well tended

- Avoid having blood tests taken from the affected limb

- Treat fungal infections of hands and feet early

- Keep swollen limbs elevated during rest periods to aid lymphatic circulation. Those with chronic lymphedema may benefit from compression garments.

Patients with 2 or more episodes of cellulitis may benefit from chronic suppressive antibiotic treatment with low-dose penicillin V or erythromycin, for one to two years.

Cellulitis prognosis

Occasionally, cellulitis can result in bacteremia and rarely in deep tissue infections, such as septic thrombophlebitis, suppurative arthritis, osteomyelitis, and infective endocarditis. Patients with impaired lymphatic drainage of the limbs or those who have undergone saphenous vein removal for coronary artery bypass grafting are at increased risk of recurrent infection 1.

Eye cellulitis

Cellulitis is a common, potentially serious bacterial infection of the skin (the lower dermis) and subcutaneous tissues (just under the skin). The affected skin appears swollen and red (but this may be less obvious on brown or black skin) and is typically painful and warm to the touch 1, 2, 3, 4, 5, 6. The skin may look pitted, like the peel of an orange, or blisters may appear on the affected skin 7. Cellulitis is sometimes accompanied by fever, chills, and general fatigue. Cellulitis can appear anywhere on the body, but it is most common on the feet and legs 7. Cellulitis is usually caused by a bacterial infection and can become serious if not treated with antibiotics. The most common bacteria are Staphylococcus aureus (golden Staph) and group A beta-hemolytic Streptococcus (Streptococcus pyogenes). These bacteria are able to enter the skin through small cracks (fissures) or normal skin, and can spread easily to the tissue under the skin.

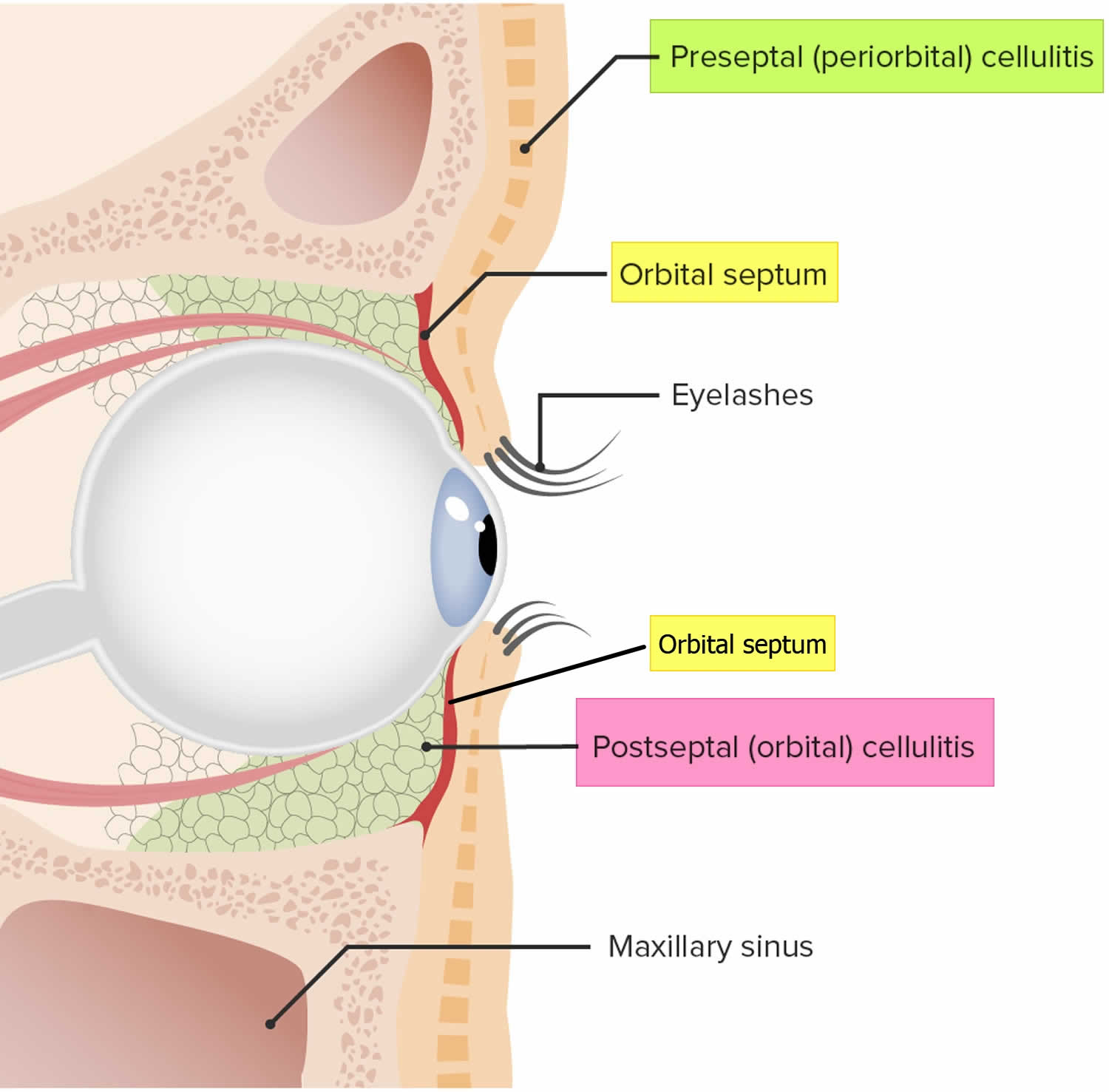

There are two types of cellulitis that affect the eyes 15:

- Preseptal cellulitis also known as periorbital cellulitis, is cellulitis around eye that only involves the eyelid tissue anterior to the orbital septum (Figures 1, 2 & 3). Preseptal cellulitis or periorbital cellulitis usually happens in children, especially young children.

- Orbital cellulitis is cellulitis is cellulitis that affects the soft tissues of the eye socket (the orbit) behind the orbital septum (i.e., cellulitis involving the orbital fat, extraocular muscles, and bony structures). Orbital cellulitis can cause the eye or eyelid to swell, keeping the eye from moving properly (Figures 1, 4 & 5). Orbital cellulitis is a serious condition. It often needs to be treated more aggressively than preseptal cellulitis.

Cellulitis is serious because the infection spreads quickly. That is why it must be treated right away.

If you think you or your child in your care has cellulitis, it’s important to get medical attention soon as possible!

If cellulitis around eye is not treated immediately, cellulitis can cause vision loss or even spread throughout your body. Left untreated, cellulitis can result in pockets of pus (abscesses) or the bacteria can spread into your bloodstream (bacteremia) and rapidly become life-threatening.

It appears that as more people are getting flu vaccinations, fewer people are getting cellulitis—especially pre-septal cellulitis 15.

Table 1. Clinical, historical, and diagnostic characteristics of preseptal cellulitis (periorbital cellulitis) and orbital cellulitis.

| Characteristic | Preseptal Cellulitis | Orbital Cellulitis |

|---|---|---|

| Eye pain | May be present | Yes |

| Eyelid erythema (redness) and/or tenderness | Yes | Yes |

| Pain with eye movements | No | May be present |

| Ophthalmoplegia (paralysis or weakness of the eye muscles) ± diplopia (double vision) | No | May be present* |

| Proptosis (bulging eye) | No | May be present* |

| Vision loss | No | May be present* |

| Relative afferent pupillary defect (RAPD) | No | May be present* |

| Fever | Usually not present | Usually present |

| Intraocular Pressure (IOP) | Normal | May be elevated* |

| Resistance to retropulsion | None | Present* |

| History of sinusitis | May be present, but often not | Present more often than not |

| CT or MRI imaging | Shows inflammation only anterior to the orbital septum | Show post-septal involvement of the inflammation. |

| Blood cultures | Very rarely has bacteremia | Bacteremia may be present |

Footnote: *Emergent signs and symptoms that might warrant immediate lateral canthotomy or cantholysis

[Source 16 ]Figure 4. Orbital septum anatomy

Footnote: The orbital septum is a membranous layer arising from the orbital periosteal lining that extends into the tarsal plates of the eyelids that provides structural support to the eye and acts as a barrier preventing bacterial spread. The orbital septum divides the eye into 2 compartments 1) Preseptal: anterior to the septum; 2) Postseptal: posterior to the septum

Figure 5. Periorbital cellulitis (also called preseptal cellulitis)

Figure 6. Orbital cellulitis

Figure 7. Preseptal cellulitis (also called periorbital cellulitis)

Figure 8. Orbital cellulitis

[Source 16 ]What are the symptoms of eye cellulitis?

Eye cellulitis symptoms include:

- bulging eye (proptosis)

- swelling of the eyelid or tissue around the eye

- red eyelids

- problems moving your eye (ophthalmoplegia)

- blurry vision or double vision (diplopia)

- fever

- feeling as if you do not have much energy or lethargy

- problems seeing well

Cellulitis eye diagnosis

To see if you have an eye cellulitis, your doctor will ask if you have had any recent surgery or dental work. They will also ask if you have had recent face or skin wounds, and chest, lung or sinus infections.

Your doctor will also examine your eyes.

To diagnose the type of infection you have, your doctor will probably do some tests. If they think you might have preseptal cellulitis, they may test tissue from your nose or eye. If they suspect orbital cellulitis, they may do a blood test.

In some cases, your doctor may also have you get a scan of the affected area. These images will help your doctor see where the infection is within the orbit.

Cellulitis eye treatment

In most cases, your doctor will have you take an antibiotic medicine to treat your cellulitis.

With pre-septal cellulitis, you should start to notice the infection getting better in about a day or two while taking antibiotics.

Because it is more serious, orbital cellulitis may not improve with (oral) antibiotics. If that happens, you may need to stay in the hospital to be treated with intravenous (IV) antibiotics. Your doctor will give you special antibiotics continuously through a vein in your body.

In some cases, your doctor may need to drain fluid from the infected area. Sometimes this can be performed in your doctor’s office. Other times, it may mean having surgery in a hospital or outpatient clinic.

Your doctor will explain the cellulitis treatment chosen for you. If you have any questions, be sure to ask.

Periorbital cellulitis

Periorbital cellulitis also called preseptal cellulitis, is a localized cellulitis of the tissues anterior (in front) to the orbital septum that involves the eyelid (Figures 1, 2 & 3). The orbital septum is a fibrous tissue that divides the orbit contents in two compartments: preseptal (anterior to the septum) and postseptal (posterior to the septum). Periorbital cellulitis or preseptal cellulitis usually affects only one eye and doesn’t travel to the other. Preseptal cellulitis or periorbital cellulitis usually happens in children, especially children younger than 6 years.

Is periorbital cellulitis contagious?

Cellulitis doesn’t usually spread from person to person. Cellulitis is an infection of the deeper layers of the skin most commonly caused by bacteria that normally live on the skin’s surface. You have an increased risk of developing cellulitis if you have:

- Injury (especially on the face). Any cut, fracture, burn or scrape gives bacteria an entry point.

- Dental surgery or other surgery of the head and neck

- Sinus infection

- Weakened immune system. Conditions that weaken your immune system — such as diabetes, leukemia and HIV/AIDS — leave you more susceptible to infections. Certain medications also can weaken your immune system.

- Skin conditions. Conditions such as eczema and insect bites can cause breaks in the skin, which give bacteria an entry point.

- Asthma

- History of cellulitis. Having had cellulitis before makes you prone to develop it again.

- Obesity. Being overweight or obese increases your risk of developing cellulitis.

However, direct person-to-person transmission of group A strep (Streptococcus pyogenes) can occur through contact with skin lesions or exposure to respiratory droplets 6. People with active infection are more likely to transmit group A strep (Streptococcus pyogenes) compared to asymptomatic carriers. Local dermatophyte (fungal) infection (e.g., athlete’s foot) may serve as portal of entry for group A strep (Streptococcus pyogenes) 1.

The spread of all types of group A strep (Streptococcus pyogenes) infection can be reduced by good hand hygiene, especially after coughing and sneezing, and respiratory etiquette (e.g., covering your cough or sneeze). Early identification and management of superficial skin lesions is also key to cellulitis prevention. Patients with recurrent cellulitis on their leg or foot should be inspected for tinea pedis and should be treated if present. Traumatic or bite wounds should be cleaned and managed appropriately (e.g., antibiotic prophylaxis, surgical debridement if indicated) to prevent secondary infections 4.

Periorbital cellulitis causes

The majority of periorbital cellulitis are caused by bacteria. Gram positive cocci are the most prevalent microorganisms identified in preseptal cellulitis, typically Staphylococcus and Streptococcus species (pyogenes and pneumonia) 17. Staphylococcus aureus and Staphylococcus epidermidis are commonly found after a penetrating eyelid trauma 17. Streptococcus pneumoniae is a common bacteria found in preseptal cellulitis secondary to sinusitis 17. In the era before the establishment of the universal vaccination against Haemophilus influenzae type b (Hib), this was a frequent bacteria especially in children under 5 years of age. It is still common in unvaccinated patients. In preseptal cellulitis secondary to a human bite it is frequent to isolate anaerobic bacteria such as Clostridium.

Adenovirus, herpes simplex and varicella zoster are also associated to cellulitis. In the immunocompromised patient fungi are often found to be the possible infective organisms.

There are three main routes for pathogen inoculation in the periorbital tissues 17:

- Direct inoculation: after eyelid trauma and infected insect bites.

- Spread from contiguous structures: paranasal sinuses are the most common (specially the ethmoids, since nerves and vessels traverse the lamina papyracea that divides the ethmoids sinuses from the orbit), chalazia/hordeolum, dacryocystitis, dacryoadenitis, canaliculitis, impetigo, erysipela, herpes simplex and herpes zoster skin lesions, endophthalmitis.

- Hematogenous: via blood vessels from an upper respiratory tract or a middle ear infection.

The venous drainage of the orbit, eyelids and sinuses goes primarily to the superior and inferior orbital veins, which drain to the cavernous sinus. Because these veins are devoid of valves, infection easily can spread to preseptal and postseptal space, and can also lead to cavernous sinus thrombosis.

Periorbital cellulitis signs and symptoms

Periorbital cellulitis or preseptal cellulitis patients often complain of eyelid swelling and redness. But also general malaise and low grade fever are commonly reported. Among the classic signs of preseptal cellulitis or periorbital cellulitis are eyelid swelling (edema), eyelid redness (erythema), eyelid warmth and fever. There are clinical keys that help us distinguish between preseptal cellulitis (periorbital cellulitis) and orbital cellulitis.

- Preseptal cellulitis: eyelid swelling (edema) and eyelid redness (erythema), normal visual acuity, absence of proptosis (bulging eyeball), pupil with normal reaction to light, normal color saturarion, normal conjunctiva and normal ocular movements.

- Orbital cellulitis: eyelid swelling (edema) and eyelid redness (erythema), diminished visual acuity, proptosis (bulging eyeball) is present, relative afferent pupillary defect may be present, reduced color saturation, chemotic conjunctiva and reduced extraocular movements with pain elicited by these movements.

Cellulitis may extend to the cheek and forehead. Also, it is common to see an eyelid abscess associated with preseptal cellulitis, which may require incision and drainage.

It is useful to delineate the area of the face affected with cellulitis using a skin marker, in order to monitor progression along time. Photographs are also an invaluable tool.

Periorbital cellulitis diagnosis

To see if you have a periorbital cellulitis, your doctor will ask if you have had any recent surgery or dental work. They will also ask if you have had recent face or skin wounds, and chest, lung or sinus infections.

Your doctor will also examine your eyes.

To diagnose the type of infection you have, your doctor will probably do some tests. If they think you might have preseptal cellulitis, they may test tissue from your nose or eye. If they suspect orbital cellulitis, they may do a blood test.

In some cases, your doctor may also have you get a scan of the affected area. These images will help your doctor see where the infection is within the orbit.

Tests for periorbital cellulitis:

- Complete blood count to document leukocytosis.

- CT scan: Sometimes the eyelid edema is so severe that precludes eye examination, thus making the distinction between preseptal and orbital cellulitis impossible. In these cases, it is useful to order a CT scan of the orbit and sinuses (to diagnose an associated sinusitis).

- Cultures of the eyelid wound (if evident), conjunctiva, blood (if febrile), abscess contents (if present and drained) or paranasal sinus secretion. These are important in order to prescribe the most appropriate antibiotic according to bacteria sensitivity.

- Lymph nodes of the head and neck to asses for lymphadenopathy.

- Check for signs of meningeal irritation to evaluate the presence of intracranial complications.

Periorbital cellulitis differential diagnosis

Periorbital cellulitis differential diagnosis may include:

- Orbital cellulitis.

- Adenoviral keratoconjunctivitis.

- Allergic conjunctivitis.

- Contact dermatitis.

- Kawasaki’s disease (children).

- Idiopathic orbital inflammation.

- Thyroid eye disease.

- Dacryocystitis.

- Dacryoadenitis.

Periorbital cellulitis treatment

Once diagnosed, preseptal cellulitis can be treated in an outpatient or inpatient basis depending on the characteristics of the patient.

If the patient is afebrile with a mild preseptal cellulitis he can be followed as an outpatient with oral antibiotics and daily visits to monitor the progress of the disease. However, if the patient does not respond to oral antibiotics in 48 hours or if extension of the infectious process into the orbit is suspected, he or she should be admitted to the hospital: a CT scan must be performed to evaluate for orbital extension, and intravenous antibiotics must be indicated.

Usually children under 2 years of age or febrile patients with a severe cellulitis are managed with intravenous antibiotics during hospitalization, with close followup. Hospitalization is also recommended in patients who cannot be followed up as outpatients. Intravenous antibiotics are usually indicated for two or three days, depending on improvement. If the condition improves, treatment can be switched to the appropriate oral antibiotics based on cultures.

These patients should be treated by a multidisciplinary team: ophthalmologist, pediatrician/primary care physician and ENT (in case of an associated sinusitis).

Antibiotics for periorbital cellulitis

Broad spectrum antibiotics must be prescribed to cover gram positive and gram negative bacteria.

Oral antibiotics

- Against gram positive and negative bacteria: Ampicillin, Amoxicillin/clavulanate, Fluoroquinolones (levofloxacin), Azithromicin (also covers some anaerobic bacteria), Clindamycin.

- Against gram positive (Staphylococcus) in case of an evident eyelid trauma: Dicloxacillin, Flucloxacillin, first generation cephalosporins (cefalexine, cefazolin).

Intravenous antibiotics. These antibiotics provide coverage to gram positive and gram negative bacteria.

- Third-generation cephalosporins (these medications are less sensitive to beta-lactamase producing bacteria such as Staphylococcus aureus): Ceftriaxone, cefotaxime, ceftazidime.

- Ampicillin/sulbactam.

The results of antibiotic sensitivities should guide the treatment whenever possible. When the cultures reveal a methicillin-resistant Staphylococcus aureus (MRSA) the therapy choice must be reevaluated.

Community associated MRSA is susceptible to these antibiotics administered in an oral route:

- Trimethoprim-Sulfamethoxazole.

- Rifampin.

- Clindamycin.

- Fluoroquinolones.

Hospital-associated MRSA is susceptible only to:

- Intravenous Vancomycin.

- PO Linezolid.

If there was a penetrating eyelid injury with organic material or a human bite, antibiotics should also cover anaerobic organisms: Metronidazole, Clindamycin, Piperacillin-Tazobactam.

If an abscess localized in the preseptal space develops, it should be incised and drained. The surgeon must not open the orbital septum during the procedure, since this may spread the infection to the postseptal space and aggravate the infection. The contents of the abscess should be cultured to determine appropriate antibiotic therapy.

Periorbital cellulitis prognosis

Periorbital cellulitis prognosis is usually good when the cellulitis is promptly diagnosed and treated. However, complications can develop even with prompt treatment.

- Orbital extension and complications: orbital cellulitis, subperiosteal abscess, orbital abscess, cavernous sinus thrombosis.

- Central nervous system involvement (after orbital extension): meningitis, abscesses (brain, extradural or subdural).

- Necrotizing fasciitis: it is a rare complication caused by β-hemolytic Streptococcus. It presents as a rapidly progressive cellulitis with poorly demarcated borders and violaceous skin discoloration, which can lead to necrosis and toxic shock syndrome. The patient must be admitted to the hospital, intravenous fluids should be replenished, IV broad spectrum antibiotics must be prescribed and surgical debridement could be necessary.

Orbital cellulitis

Orbital cellulitis is cellulitis that affects the soft tissues of the eye socket (the orbit) behind the orbital septum (i.e., cellulitis involving the orbital fat, extraocular muscles, and bony structures). Orbital cellulitis can cause the eye or eyelid to swell, keeping the eye from moving properly (Figures 1, 4 & 5). Orbital cellulitis most commonly refers to an acute spread of infection into the eye socket from either extension from periorbital structures (most commonly the adjacent ethmoid or frontal sinuses (90%), skin, dacryocystitis, dental infection, intracranial infection), exogenous causes (trauma, foreign bodies, post-surgical), intraorbital infection (endopthalmitis, dacryoadenitis), or from spread through the blood (bacteremia with septic emboli) 18. Risk factors for orbital cellulitis include recent upper respiratory illness, acute or chronic bacterial sinusitis, trauma, ocular or periocular infection, or systemic infection.

Orbital cellulitis can be caused by an extension from periorbital structures (paranasal sinuses, face and eyelids, lacrimal sac, dental structures). Orbital cellulitis cause can also be exogenous (trauma, foreign body, surgery), endogenous (bacteremia with septic embolization), or intraorbital (endophthalmitis, dacryoadenitis) 19. The orbital tissues are infiltrated by acute and chronic inflammatory cells and the infectious organisms may be identified on the tissue sections. The organisms are best identified by microbiologic culture. The most common infectious pathogens include gram positive Streptococcal and Staphylococcal species. In a study by Harris et al 20, it was noted that in children younger than 9 years of age, the infections are typically from one aerobic organism; in children older than 9 years of age and in adults, the infections may be polymicrobial with both aerobic and anaerobic bacteria.

Orbital cellulitis is a serious condition. Orbital cellulitis often needs to be treated more aggressively than preseptal cellulitis.

Admission to the hospital is warranted in all cases of orbital cellulitis. A complete blood count with differential, blood cultures, and nasal and throat swabs should be ordered. The diagnosis of orbital cellulitis is based on clinical examination.

Is orbital cellulitis contagious?

Cellulitis doesn’t usually spread from person to person. Cellulitis is an infection of the deeper layers of the skin most commonly caused by bacteria that normally live on the skin’s surface. You have an increased risk of developing cellulitis if you have:

- Injury (especially on the face). Any cut, fracture, burn or scrape gives bacteria an entry point.

- Dental surgery or other surgery of the head and neck

- Sinus infection

- Weakened immune system. Conditions that weaken your immune system — such as diabetes, leukemia and HIV/AIDS — leave you more susceptible to infections. Certain medications also can weaken your immune system.

- Skin conditions. Conditions such as eczema and insect bites can cause breaks in the skin, which give bacteria an entry point.

- Asthma

- History of cellulitis. Having had cellulitis before makes you prone to develop it again.

- Obesity. Being overweight or obese increases your risk of developing cellulitis.

However, direct person-to-person transmission of group A strep (Streptococcus pyogenes) can occur through contact with skin lesions or exposure to respiratory droplets 6. People with active infection are more likely to transmit group A strep (Streptococcus pyogenes) compared to asymptomatic carriers. Local dermatophyte (fungal) infection (e.g., athlete’s foot) may serve as portal of entry for group A strep (Streptococcus pyogenes) 1.

The spread of all types of group A strep (Streptococcus pyogenes) infection can be reduced by good hand hygiene, especially after coughing and sneezing, and respiratory etiquette (e.g., covering your cough or sneeze). Early identification and management of superficial skin lesions is also key to cellulitis prevention. Patients with recurrent cellulitis on their leg or foot should be inspected for tinea pedis and should be treated if present. Traumatic or bite wounds should be cleaned and managed appropriately (e.g., antibiotic prophylaxis, surgical debridement if indicated) to prevent secondary infections 4.

Orbital cellulitis causes

Orbital cellulitis most commonly occurs when a bacterial infection spreads from the paranasal sinuses into the orbit 18. In children under the age of 10 years, paranasal sinusitis most often involves the ethmoid sinus which spreads through the thin lamina papyracea of the medial orbital wall into the orbit. It can also occur when an eyelid skin infection, an infection in an adjacent area, or an infection in the blood stream spreads into the orbit. The drainage of the eyelids and sinuses occurs largely through the orbital venous system: more specifically, through the superior and inferior orbital veins that drain into the cavernous sinus. This venous system is devoid of valves and for this reason infection might spread, in preseptal and orbital cellulitis, into the cavernous sinus causing a sight threatening complication such as cavernous sinus thrombosis.

The most common pathogens in orbital cellulitis are Gram positive Streptococcus and Staphylococcus species. Streptococcal infections are identified on culture by their formation of pairs or chains. Streptococcal pyogenes (group A beta-hemolytic Streptococcus) requires blood agar to grow and exhibits clear (beta) hemolysis on blood agar 18. Streptococcus such as Streptococcus pneumonia produce green (alpha) hemolysis, or partial reduction of red blood cell hemoglobin 18. Staphylococcal species appear as a cluster arrangement on gram stain. Staphylococcus aureus (golden Staph) forms a large yellow colony on rich medium in distinction to Staphylococcus epidermidis which forms white colonies 18. Gram negative rods can be seen in both orbital cellulitis related to trauma and in neonates and immunosuppressed patients. Anaerobic bacteria such as Peptococcus, Peptostreptococcus, and Bacteroides can be involved in infections extending from sinusitis in adults and older children 18. Fungal infections with either Mucor or Aspergillus need to be considered in immunocompromised or diabetic patients; immunocompetent patients may also have fungal infections in rare cases 18.

Orbital cellulitis pathophysiology

Orbital cellulitis most commonly occurs in the setting of an upper respiratory or sinus infection 18. The human upper respiratory tract is normally colonized with Streptococcus pneumoniae and infection can occur through several mechanisms. Streptococcal pyogenes (group A beta-hemolytic Streptococcus) infections also occur primarily in the respiratory tract. The complex cell surface of this Gram-positive organism determines its virulence and ability to invade the surrounding tissue and incite inflammation. Staphylococcus aureus (golden Staph) infections occur commonly in the skin and spread to the orbit from the skin. Staphylococcal organisms also produce toxins which help to promote their virulence and leads to the inflammatory response seen in these infections. The inflammatory response elicited by all these pathogens plays a major role in tissue destruction in the orbit.

Orbital cellulitis prevention

Identifying patients and effectively treating upper respiratory or sinus infections before they evolve into orbital cellulitis is an important aspect of preventing preseptal cellulitis from progressing to orbital cellulitis 18. Equally important in preventing orbital cellulitis is prompt and appropriate treatment of preseptal skin infections as well as infections of the teeth, middle ear, or face before they spread into the orbit.

Orbital cellulitis signs and symptoms

As a preseptal infection progresses into the orbit, the inflammatory signs typically increase with increasing redness and swelling of the eyelid with a secondary ptosis (droopy eyelid). As the infection worsens, proptosis (bulging eyeball) develops and extraocular motility becomes compromised causing ophthalmoplegia (paralysis or weakness of the eye muscles). When the optic nerve is involved, loss of visual acuity is noted and an afferent pupillary defect can be appreciated. The intraocular pressure (IOP) often increases and the orbit becomes resistant to retropulsion. The skin can feel warm to the touch and pain can be elicited with either touch or eye movements. Examination of the nose and mouth is also warranted in order to look for any black eschar which would suggest a fungal infection. Purulent nasal discharge with hyperemic nasal mucosa may be present.

Systemic symptoms including fever and lethargy may or may not be present. Change in the appearance of the eyelids with redness and swelling is frequently a presenting symptom. Pain, particularly with eye movement, is commonly noted. Diplopia (double vision) may also occur.

Orbital cellulitis complications

The complications of orbital cellulitis are threatening and include severe exposure keratopathy (damage to the cornea) with secondary ulcerative keratitis, neutrophic keratitis, secondary glaucoma, septic uveitis or retinitis, exudative retinal detachment, inflammatory or infectious neuritis, optic neuropathy, panophthalmitis (inflammation of the interior of the eye involving the vitreous humor), cranial nerve palsies, optic nerve edema, subperiosteal abscess, orbital abscess, central retinal artery occlusion, retinal vein occlusion, blindness, orbital apex syndrome, cavernous sinus thrombosis, meningitis, subdural or brain abscess, and death.

Orbital cellulitis diagnosis

Admission to the hospital is warranted in all cases of orbital cellulitis. A complete blood count with differential, blood cultures, and nasal and throat swabs should be ordered. The diagnosis of orbital cellulitis is based on clinical examination. The presence of the following signs is suggestive of orbital involvement: proptosis (bulging eyeball), swelling or edema of the conjunctiva (chemosis), pain with eye movements, ophthalmoplegia (paralysis or weakness of the eye muscles), diplopia (double vision), optic nerve involvement as well as fever, leukocytosis (75% of cases), and lethargy. Other signs and symptoms include runny nose (rhinorrhea), headache, tenderness on palpation, and eyelid edema. Intraocular pressure may be elevated if there is increased venous congestion. In addition to clinical suspicion, diagnostic imaging using computed tomography (CT) may help distinguish between preseptal and orbital cellulitis while also looking for complications of orbital cellulitis.

Physical examination

Physical examination should include:

- Best-corrected visual acuity (BCVA). Decreased vision might be indicative of optic nerve involvement or could be secondary to severe exposure keratopathy or retinal vein occlusion.

- Color vision assessment to assess the presence of optic nerve involvement.

- Proptosis measurements using Hertel exophthalmometry.

- Visual field assessment via confrontation.

- Assessment of pupillary function with particular attention paid to the presence of a relative afferent pupillary defect (RAPD).

- Ocular motility and presence of pain with eye movements. Also, there might be involvement of the III, IV, and V1/V2 cranial nerve in cases of cavernous sinus involvement.

- Orbit exam should include documentation of direction of displacement of globe (e.g. a superior subperiosteal abscess will displace the globe inferiorly), resistance to retropulsion on palpation, unilateral or bilateral involvement (bilateral involvement is virtually diagnostic of cavernous sinus thrombosis) 21.

- Measurement of intraocular pressure (IOP). Increased venous congestion may result in increased intraocular pressure (IOP).

- Slit-lamp biomicroscopy of the anterior segment if possible to look for signs of exposure keratopathy in cases of severe proptosis.

- Dilated fundus exam will exclude or confirm the presence of optic neuropathy or retinal vascular occlusion.

Diagnostic procedures

Computed tomography (CT) of the orbit is the imaging modality of choice for patients with orbital cellulitis. Most of the time, CT is readily available and will give the clinician information regarding the presence of sinusitis, subperiosteal abscess, stranding of orbital fat, or intracranial involvement. Nevertheless, in cases of mild to moderate orbital cellulitis with no optic nerve involvement, the initial management of the patient remains medical. Imaging is warranted in children and in cases of poor response to intravenous antibiotics with progression of orbital signs in order to confirm the presence of complications such as subperiosteal abscess or intracranial involvement. Although a magnetic resonance imaging (MRI) scan is safer in children since there is no risk of radiation exposure, the long acquisition time and the need for prolonged sedation make CT scan the imaging modality of choice. However, if there is suspicion of a concomitant cavernous sinus thrombosis, MRI may be a useful adjunct to a CT scan.

Orbital cellulitis treatment

The management of orbital cellulitis requires admission to the hospital and initiation of broad-spectrum intravenous antibiotics that address the most common pathogens 18. A multi-disciplinary approach is usually warranted for patients with orbital cellulitis under the care of pediatricians, ENT surgeons, ophthalmologists, and infectious disease specialists. Blood cultures and nasal and throat swabs may be undertaken, and the antibiotics should be modified based on the results. In infants with orbital cellulitis, a 3rd generation cephalosporin is usually initiated such as cefotaxime, ceftriaxone or ceftazidime along with a penicillinase-resistant penicillin 18. In older children, since sinusitis is most commonly associated with aerobic and anaerobic organisms, clindamycin might be another option 18. Metronidazole is also being increasingly used in children. If there is concern for MRSA infection, vancomycin may be added as well 22. The antibiotic regimen should be modified based on the results of the cultures if needed. Intravenous corticosteroids may also be of benefit in the management of pediatric orbital cellulitis 23, 24, 25.

Medical follow up

The patient should be followed closely in the hospital setting for progression of orbital signs and development of complications such as cavernous sinus thrombosis or intracranial extension, which can be lethal 21. Once improvement has been documented with 48 hours of intravenous antibiotics, consideration for switching to oral antibiotics may be appropriate.

Surgery

The prevalence of subperiosteal or orbital abscess complicating an orbital cellulitis approaches 10% 18. The clinician should suspect the presence of such an entity if there is progression of orbital signs, and/or systemic compromise despite the initiation of appropriate intravenous antibiotics for at least 24-48 hours 18. In these cases, a contrast-enhanced CT scan should be ordered to evaluate the orbit, the paranasal sinuses, and/or the brain 18. If there is associated sinusitis, ENT should be consulted. If an orbital abscess is present it should be drained. The management of subperiosteal abscess remains controversial since there are cases of resolution with the use of intravenous antibiotics only. As a general recommendation, observation with intravenous antibiotics only (i.e. no drainage of the subperiosteal abscess) is indicated when 20, 26, 27:

- Child is under the age of 9 years

- No intracranial involvement

- Medial wall abscess is of moderate or smaller size

- No vision loss or afferent pupillary defect

- No frontal sinus involvement

- No dental abscess

If there is evidence of intracranial extension of the infection, evidence of optic nerve compromise, clinical deterioration despite 48 hours of intravenous antibiotics, suspicion of anaerobic infection (e.g. presence of gas in abscess on CT), or recurrence of subperiosteal abscess after prior drainage, surgery is almost always indicated 19. At the time of surgery, cultures and susceptibility testing may be obtained from samples to help tailor therapy.

Orbital cellulitis prognosis

With prompt recognition and aggressive medical and/or surgical treatment, the prognosis is excellent.

- Stevens DL, Bryant AE. Impetigo, Erysipelas and Cellulitis. 2016 Feb 10. In: Ferretti JJ, Stevens DL, Fischetti VA, editors. Streptococcus pyogenes : Basic Biology to Clinical Manifestations [Internet]. Oklahoma City (OK): University of Oklahoma Health Sciences Center; 2016-. Available from: https://www.ncbi.nlm.nih.gov/books/NBK333408[↩][↩][↩][↩][↩][↩]

- Bisno AL, Stevens DL. Streptococcal infections of skin and soft tissues. N Engl J Med. 1996 Jan 25;334(4):240-5. doi: 10.1056/NEJM199601253340407[↩][↩]

- Sigrídur Björnsdóttir, Magnús Gottfredsson, Anna S. Thórisdóttir, Gunnar B. Gunnarsson, Hugrún Ríkardsdóttir, Már Kristjánsson, Ingibjörg Hilmarsdóttir, Risk Factors for Acute Cellulitis of the Lower Limb: A Prospective Case-Control Study, Clinical Infectious Diseases, Volume 41, Issue 10, 15 November 2005, Pages 1416–1422, https://doi.org/10.1086/497127[↩][↩]

- Dennis L. Stevens, Alan L. Bisno, Henry F. Chambers, E. Patchen Dellinger, Ellie J. C. Goldstein, Sherwood L. Gorbach, Jan V. Hirschmann, Sheldon L. Kaplan, Jose G. Montoya, James C. Wade, Practice Guidelines for the Diagnosis and Management of Skin and Soft Tissue Infections: 2014 Update by the Infectious Diseases Society of America, Clinical Infectious Diseases, Volume 59, Issue 2, 15 July 2014, Pages e10–e52, https://doi.org/10.1093/cid/ciu296[↩][↩][↩][↩][↩][↩][↩][↩][↩][↩][↩][↩]

- Karppelin M, Siljander T, Vuopio-Varkila J, Kere J, Huhtala H, Vuento R, Jussila T, Syrjänen J. Factors predisposing to acute and recurrent bacterial non-necrotizing cellulitis in hospitalized patients: a prospective case-control study. Clin Microbiol Infect. 2010 Jun;16(6):729-34. doi: 10.1111/j.1469-0691.2009.02906.x[↩][↩]

- Efstratiou A, Lamagni T. Epidemiology of Streptococcus pyogenes. 2016 Feb 10 [Updated 2017 Apr 3]. In: Ferretti JJ, Stevens DL, Fischetti VA, editors. Streptococcus pyogenes : Basic Biology to Clinical Manifestations [Internet]. Oklahoma City (OK): University of Oklahoma Health Sciences Center; 2016-. Available from: https://www.ncbi.nlm.nih.gov/books/NBK343616[↩][↩][↩][↩][↩]

- Cellulitis: All You Need to Know. https://www.cdc.gov/groupastrep/diseases-public/cellulitis.html[↩][↩][↩][↩]

- Dire DJ, Coppola M, Dwyer DA, Lorette JJ, Karr JL. Prospective evaluation of topical antibiotics for preventing infections in uncomplicated soft-tissue wounds repaired in the ED. Acad Emerg Med. 1995;2(1):4–10.[↩]

- Sibbald RG, Goodman L, Woo KY, et al. Special considerations in wound bed preparation 2011: an update. Adv Skin Wound Care. 2011;24(9):415–436.[↩]

- Okan D, Woo K, Ayello EA, Sibbald G. The role of moisture balance in wound healing. Adv Skin Wound Care. 2007;20(1):39–53.[↩]

- Agren MS, Karlsmark T, Hansen JB, Rygaard J. Occlusion versus air exposure on full-thickness biopsy wounds. J Wound Care. 2001;10(8):301–304.[↩]

- Centers for Disease Control and Prevention (CDC). Updated recommendations for use of tetanus toxoid, reduced diphtheria toxoid and acellular pertussis (Tdap) vaccine from the Advisory Committee on Immunization Practices, 2010. MMWR Morb Mortal Wkly Rep. 2011;60(1):13–15.[↩]

- Immunization Action Coalition. Ask the experts: diseases & vaccines. Diphtheria, tetanus, and pertussis. http://www.immunize.org/askexperts/experts_per.asp[↩]

- Cellulitis. https://dermnetnz.org/topics/cellulitis[↩]

- What Is Cellulitis? https://www.aao.org/eye-health/diseases/what-is-cellulitis[↩][↩]

- Preseptal vs Orbital Cellulitis. https://morancore.utah.edu/basic-ophthalmology-review/preseptal-vs-orbital-cellulitis[↩][↩]

- Preseptal Cellulitis. https://eyewiki.org/Preseptal_Cellulitis[↩][↩][↩][↩]

- Orbital Cellulitis. https://eyewiki.org/Orbital_Cellulitis[↩][↩][↩][↩][↩][↩][↩][↩][↩][↩][↩][↩][↩][↩][↩]

- Basic and Clinical Science Course 2019-2020: Oculofacial Plastic and Orbital Surgery. San Francisco, CA: American Academy of Ophthalmology; 2019.[↩][↩]

- Harris GJ. Subperiosteal abscess of the orbit. Age as a factor in the bacteriology and response to treatment. Ophthalmology. 1994 Mar;101(3):585-95. doi: 10.1016/s0161-6420(94)31297-8[↩][↩]

- Basic and Clinical Science Course 2019-2020: Pediatric Ophthalmology and Strabismus. San Francisco, CA: American Academy of Ophthalmology; 2019.[↩][↩]

- Liao S, Durand ML, Cunningham MJ. Sinogenic orbital and subperiosteal abscesses: microbiology and methicillin-resistant Staphylococcus aureus incidence. Otolaryngol Head Neck Surg. 2010 Sep;143(3):392-6. doi: 10.1016/j.otohns.2010.06.818[↩]

- Yen MT, Yen KG. Effect of corticosteroids in the acute management of pediatric orbital cellulitis with subperiosteal abscess. Ophthalmic Plast Reconstr Surg. 2005 Sep;21(5):363-6; discussion 366-7. doi: 10.1097/01.iop.0000179973.44003.f7[↩]

- Chen L, Silverman N, Wu A, Shinder R. Intravenous Steroids With Antibiotics on Admission for Children With Orbital Cellulitis. Ophthalmic Plast Reconstr Surg. 2018 May/Jun;34(3):205-208. doi: 10.1097/IOP.0000000000000910[↩]

- Davies BW, Smith JM, Hink EM, Durairaj VD. C-Reactive Protein As a Marker for Initiating Steroid Treatment in Children With Orbital Cellulitis. Ophthalmic Plast Reconstr Surg. 2015 Sep-Oct;31(5):364-8. doi: 10.1097/IOP.0000000000000349[↩]

- Garcia GH, Harris GJ. Criteria for nonsurgical management of subperiosteal abscess of the orbit: analysis of outcomes 1988-1998. Ophthalmology. 2000 Aug;107(8):1454-6; discussion 1457-8. doi: 10.1016/s0161-6420(00)00242-6[↩]

- Harris GJ. Subperiosteal abscess of the orbit: computed tomography and the clinical course. Ophthalmic Plast Reconstr Surg. 1996 Mar;12(1):1-8. doi: 10.1097/00002341-199603000-00001[↩]