Skin infection

Your skin is your body’s largest organ. It has many different functions, including covering and protecting your body. It helps keep germs out. But sometimes the germs can cause a skin infection. This often happens when there is a break, cut, or wound on your skin. It can also happen when your immune system is weakened, because of another disease or a medical treatment.

Skin infections are caused by different kinds of germs ranging from the commonest bacterial Staph infection caused by the bacteria Staphylococcus aureus (S. aureus) causing cellulitis, impetigo (Streptococcus pyogenes) to fungi and yeast infections (Pityriasis versicolor [Tinea versicolor], ringworm fungus called Tinea, Athlete’s foot, Jock itch), parasites (body lice, head lice, pubic lice and scabies) and viruses (Molluscum contagiosum, shingles, warts, and herpes simplex)

Some skin infections cover a small area on the top of your skin. Other infections can go deep into your skin or spread to a larger area.

You are at a higher risk for a skin infection if you:

- Have poor circulation

- Have diabetes

- Are older

- Have an immune system disease, such as HIV and AIDS

- Have a weakened immune system because of chemotherapy or other medicines that suppress your immune system

- Have to stay in one position for a long time, such as if you are sick and have to stay in bed for a long time or you are paralyzed

- Are malnourished

- Have excessive skinfolds, which can happen if you have obesity

- Injury to the skin

- Have skin conditions, such as dermatitis or eczema

- Have chronic swelling of the legs or arms (lymphedema)

Skin infection symptoms depend on the type of infection. Some symptoms that are common to many skin infections include rashes, swelling, redness, pain, pus, and itching.

To diagnose a skin infection, your doctor will perform a physical exam and ask about your symptoms. You may have lab tests, such as a skin or wound swabs and culture. This is a test to identify what type of infection you have, using a sample from your skin. Your doctor may take the sample by swabbing or scraping your skin, or removing a small piece of skin (biopsy). Sometimes doctors use other tests, such as blood tests.

The treatment of a skin infection depends on the type of infection, the severity and location of the infection and your overall health and immune status and how serious it is. Some skin infections will go away on their own. When you do need treatment, it may include a cream or lotion to put on the skin. Other possible treatments include medicines(antibiotics, anti-fungals or anti-virals) and a procedure to drain pus.

Bacterial skin infection

Some bacteria live on normal skin and cause no harm, but some bacteria (listed below) invade normal skin, broken skin from eczema or dermatitis or wounds causing infection. Staphylococcus aureus or Staphylococci (‘staph’) are a common type of bacteria that live on your skin and mucous membranes (for example, in the nostrils) of humans. Staphylococcus aureus (S. aureus) is the most important of these bacteria in human diseases. Other staphylococci, including Staphylococcus epidermidis, are considered commensals or normal inhabitants of the skin surface.

About 15–40 per cent of healthy humans are carriers of Staphylococcus aureus (S. aureus), that is, they have the bacteria on their skin without any active infection or disease (colonization). The carrier sites are usually the nostrils and skin folds, where the bacteria may be found intermittently or every time they are looked for.

Bacterial skin infections develop when bacteria enter through the hair follicles or through small breaks in your skin that result from scrapes, punctures, surgery, burns, sunburn, animal or insect bites, wounds, and preexisting skin disorders. People can develop bacterial skin infections after participating in a variety of activities, for example, gardening in contaminated soil or swimming in a contaminated pond, lake, or ocean.

Some bacterial skin infections involve just the skin, and others also involve the soft tissues under the skin. Cellulitis is a common type bacterial of skin infection that involves the deeper layers of the skin that causes redness, swelling, and pain in the infected area of the skin. If untreated, cellulitis can spread and cause serious health problems. Different types of bacteria can cause cellulitis. The most common bacteria causing cellulitis are Streptococcus pyogenes (two-thirds of cases) and Staphylococcus aureus (one third). Good wound care and hygiene are important for preventing cellulitis. Another type of common bacterial skin infection is skin abscess, which is a collection of pus under the skin.

Relatively minor skin infections include:

- Carbuncles

- Ecthyma

- Erythrasma

- Folliculitis

- Furuncles

- Impetigo

- Lymphadenitis

- Small skin abscesses (pus-filled pockets in the skin)

More serious bacterial skin and skin structure infections include:

- Cellulitis

- Erysipelas

- Large skin abscesses

- Lymphangitis

- Necrotizing skin infections

- Wound infections

Bacterial skin infections can be classified as simple (uncomplicated) or complicated (necrotizing or nonnecrotizing), or as suppurative or nonsuppurative. Most community-acquired infections are caused by methicillin-resistant Staphylococcus aureus (MRSA) and beta-hemolytic streptococcus. Every year, community-acquired methicillin-resistant Staphylococcus aureus (MRSA) accounts for 59% of skin and soft tissue infections presenting to the emergency department 1. Simple skin infections are usually monomicrobial (one bacteria) and present with localized clinical findings. In contrast, complicated skin infections can be mono- or polymicrobial and may present with systemic inflammatory response syndrome (SIRS). Staphylococcal scalded skin syndrome, Scarlet fever, and toxic shock syndrome are skin-related consequences of bacterial infections.

Bacteria that cause skin infection

Many types of bacteria can infect the skin. The most common are Staphylococcus and Streptococcus. Methicillin-resistant Staphylococcus aureus (also known as MRSA) is a common bacteria causing skin infections in the United States. MRSA is resistant to many commonly used antibiotics because it has undergone genetic changes that allow it to survive despite exposure to some antibiotics. Because MRSA is resistant to several antibiotics that used to kill it, doctors tailor their treatment based on how often MRSA is found in the local area and whether or not it has been found to be resistant to commonly used antibiotics.

Staphylococcus aureus

- Folliculitis

- Furunculosis (boils) and abscesses

- Impetigo (school sores) and ecthyma

- Methicillin-resistant Staphylococcus aureus (also known as MRSA)

- Staphylococcal scalded skin syndrome

- Toxic shock syndrome

- Tropical pyomyositis

- Botryomycosis (pyoderma vegetans)

Streptococcus pyogenes

- Cellulitis

- Erysipelas

- Impetigo

- Necrotising fasciitis

- Infectious gangrene

- Scarlet fever

- Rheumatic fever, erythema marginatum

Corynebacterium species

Less common bacteria

Less common bacteria that may also cause infection include:

- Neisseria species, the cause of gonorrhea and meningococcal disease

- Erysipelothrix insidiosa, the cause of erysipeloid (usually an animal infection)

- Haemophilus species, the cause of chancroid and cellulitis in young children

- Helicobacter pylori, a stomach infection, which may be associated with some cases of chronic urticaria and rosacea

- Klebsiella rhinoscleromatis, the cause of rhinoscleroma

- Mycoplasma pneumoniae, a cause of pneumonia, causes non-specific erythema, bullous eruptions, urticarial rashes, erythema multiforme, mucositis and rarely, Stevens–Johnson syndrome and toxic epidermal necrolysis (TEN)

- Pseudomonas aeruginosa causes wound infections, athlete’s foot, gram-negative folliculitis, chronic paronychia (green nail syndrome), spa pool folliculitis and ecthyma gangrenosum

- Calymmatobacterium granulomatis, the cause of granuloma inguinale

- Bacillus anthracis, the cause of anthrax

- Clostridium perfringens and other species cause gas gangrene

- Listeria monocytogenes rarely causes cutaneous listeriosis.

- Treponema species cause syphilis, yaws and pinta

- Bartonella species cause cat scratch fever, bacillary angiomatosis, Carrion disease, and bartonellosis

- Mycobacterium species cause tuberculosis, leprosy and atypical mycobacterial infections including Buruli ulcer

- Leptospira, the cause of leptospirosis, which may cause bleeding into the skin (purpura)

- Nocardia, the cause of nocardiosis

- Yersinia pestis, the cause of bubonic plague, which causes swollen lymph glands and pustules, ulcers and scabs on the skin

- Serratia marcescens, a facultative anaerobic gram-negative bacillus that may rarely cause skin infections such as cellulitis, abscesses and ulcers; usually in patients with immunodeficiency.

- Fusobacterium species, Bacillus fusiformis, Treponema vincenti and other bacteria may result in tropical ulcer

- Burkholderia species, the cause of melioidosis and glanders, in which abscesses may be associated with systemic symptoms.

- Actinomyces species, the cause of actinomycosis, in which granular bacteriosis occurs, with abscesses and sinus tracts draining sulphur-yellow granules.

- Vibrio vulnificus, a cause of septic shock characterized by blood-filled blisters.

- Brucella species, the cause of brucellosis, a febrile illness caught from unvaccinated animals or their unpasteurized milk.

- Salmonella species, particularly S. typhi (typhoid fever)

- Aeromonas species, found in water, rarely cause skin and soft tissue infections

Tick-borne bacterial infections

Tick-borne bacterial infections include:

- Lyme disease, due to Borrelia burgdorferi

- Relapsing fever, due to Babesia microti

- Tularemia, due to Francisella tularensis

- Rickettsial diseases (some of these also transmitted by body louse, fleas, mosquitoes and mites).

- Ehrlichiosis and anaplasmosis.

Conditions sometimes caused by or associated with bacterial infection

Other conditions sometimes caused by or associated with bacterial infection include:

- Kawasaki disease (mucocutaneous lymph node syndrome)

- Folliculitis barbae (shaving bumps)

- Sarcoidosis

- Scalp folliculitis

- Osler nodes and Janeway lesions (bacterial endocarditis)

- Vaginitis and bacterial vaginosis.

Risk factor for bacterial skin infection

Some people are at particular risk of developing bacterial skin infections:

- People with diabetes, who are likely to have poor blood flow (especially to the hands and feet), have a high level of sugar (glucose) in their blood, which decreases their ability to fight infections

- People who are hospitalized or living in a nursing home

- People who are older

- People who have human immunodeficiency virus (HIV), AIDS or other immune disorders, or hepatitis

- People who are undergoing chemotherapy or treatment with other drugs that suppress the immune system

Skin that is inflamed (dermatitis) or damaged is more likely to become infected. In fact, any break in the skin predisposes a person to infection.

Bacterial skin infection prevention

Preventing bacterial skin infections involves keeping the skin undamaged and clean. When the skin is cut or scraped, the injury should be washed with soap and water and covered with a sterile bandage.

Petrolatum may be applied to open areas to keep the tissue moist and to try to prevent bacterial invasion. Doctors recommend that people do not use antibiotic ointments (prescription or nonprescription) on uninfected minor wounds because of the risk of developing an allergy to the antibiotic.

Bacterial skin infection diagnosis

Laboratory tests for bacterial skin infections may include:

- A swab of the inflamed site, such as throat, skin lesions for culture

- Complete blood count. bacterial infection often raises the white cell count with increased neutrophils

- C-reactive protein (CRP). Elevated CRP > 50 in serious bacterial infections

- Procalcitonin. Procalcitonin blood test marker for generalized sepsis due to bacterial infection

- Serology. Serology tests ten days apart to determine immune response to a particular organism

- Polymerase chain reaction (PCR) and ELISA tests for specific organisms

- Blood culture. Blood culture if high fever > 38°C

Bacterial skin infection treatment

The treatment of bacterial skin infection depends on the bacteria that is causing the infection, the severity and location of the infection and your overall health and immune status. When bacterial skin infections do occur, they can range in size from a tiny spot to the entire body surface. Bacterial skin infection can range in seriousness as well, from harmless to life threatening. Minor bacterial infections may resolve without treatment. However, persistent and serious bacterial infections are treated with antibiotics. These are available for localized topical use (creams, gels, solutions), such as antibiotics for acne, or as systemic treatment as tablets, capsules and intramuscular or intravenous injections.

It is best to take samples or swabs to test which organism is responsible for the skin infection before commencing antibiotics. If the infection is serious (e.g, if meningococcal disease is suspected), immediate treatment with a broad-spectrum antibiotic may commence. Once the specific organism causing infection has been determined, the antibiotic may be changed to a narrow-spectrum antibiotic directed against that organism.

Antibiotics have important side effects and societal impact and should not be prescribed or taken if they are not required or if they are unlikely to be of benefit, for example, if the infection is viral in origin. Antibiotic side effects can range from minor issues, like a rash, to very serious health problems, such as antibiotic-resistant infections and Clostridioides difficile infection, which causes diarrhea that can lead to severe colon damage and death. See your doctor if you develop any side effects while taking your antibiotic.

Abscesses should be cut open by a doctor and allowed to drain, and any dead tissue must be surgically removed. Antibiotics are sometimes needed for abscesses after the pus has been drained.

In some cases, severe infections need to be treated in the hospital.

Cellulitis

Cellulitis is a common, potentially serious bacterial infection of the skin (the lower dermis) and subcutaneous tissues (just under the skin). The affected skin appears swollen and red (but this may be less obvious on brown or black skin) and is typically painful and warm to the touch 2, 3, 4, 5, 6, 7. The skin may look pitted, like the peel of an orange, or blisters may appear on the affected skin 8. Cellulitis is sometimes accompanied by fever, chills, and general fatigue. Cellulitis can appear anywhere on the body, but it is most common on the feet and legs 8. Cellulitis is usually caused by a bacterial infection and can become serious if not treated with antibiotics. The most common bacteria are Staphylococcus aureus (golden Staph) and group A beta-hemolytic Streptococcus (Streptococcus pyogenes). These bacteria are able to enter the skin through small cracks (fissures) or normal skin, and can spread easily to the tissue under the skin.

Cellulitis can affect almost any part of your body (e.g., face, eye, arms and other areas). Most commonly, cellulitis occurs on the lower legs and in areas where the skin is damaged or inflamed allowing bacteria to enter. Anyone, at any age, can develop cellulitis. However, you are at increased risk if you smoke, have diabetes or poor circulation.

Left untreated, cellulitis can spread to your lymph nodes (lymphadenitis) and can result in pockets of pus (abscesses) or the bacteria can spread into your bloodstream (bacteremia) and rapidly become life-threatening. Prior to the development of antibiotics, cellulitis was fatal. With the introduction of antibiotics, most people recover fully within a week.

Cellulitis isn’t usually spread from person to person.

If you think you or someone in your care has cellulitis, it’s important to get medical attention soon as possible!

The main signs of cellulitis are skin that is red, painful, swollen, tender and warm to touch. People with severe cellulitis can get fever, chills, sweating and nausea, and might feel generally unwell.

Cellulitis often affects the lower leg, but can occur on any part of the body including the face. The infection may occur when bacteria enter the skin through an ulcer, cut or a scratch or an insect bite. However it can occur without any visible damage to the skin.

Sometimes bacteria from cellulitis spreads into the blood stream, which is called sepsis and this is a medical emergency.

People with cellulitis can quickly become very unwell and a small number of people may develop serious complications.

Antibiotics are the main treatment, usually orally at home. Some people need treatment in hospital with intravenous (IV) antibiotics. Rest and elevation (raising) of the limb are also very important. In some cases the affected limb may need compression.

After successful treatment, the skin may flake or peel off as it heals. This can be itchy.

Figure 1. Cellulitis leg

Figure 2. Cellulitis foot

Figure 3. Facial cellulitis

It’s important to identify and treat cellulitis early because the condition can spread rapidly throughout your body.

Seek emergency care if:

- You have a red, swollen, tender rash or a rash that’s changing rapidly

- You have a fever

See your doctor, preferably that day, if:

- You have a rash that’s red, swollen, tender and warm — and it’s expanding — but without fever

Who gets cellulitis?

Cellulitis affects people of all ages and races. Factors that increase the risk of developing cellulitis include:

- Previous episode(s) of cellulitis

- Skin wounds or injuries that cause a break in the skin (like cuts, ulcers, bites, puncture wounds, tattoos, piercings)

- Fissuring of toes or heels, eg due to athlete’s foot, tinea pedis or cracked heels

- Poor circulation in the legs (peripheral vascular disease)

- Venous disease, eg gravitational eczema, leg ulceration, and/or lymphedema

- Having limbs (feet, legs, hands, and arms) that stay swollen (chronic edema), including swelling due to:

- Lymphedema (problems with the lymphatic system so it does not drain the way it should); the lymphatic system is a part of the body’s immune system that helps move fluid that contains infection-fighting cells throughout the body

- Coronary artery bypass grafting (having a healthy vein removed from the leg and connected to the coronary artery to improve blood flow to the heart)

- Bites from insects, animals, or other humans

- Chronic lower leg swelling (edema)

- Current or prior injury, eg trauma, surgical wounds, radiotherapy

- Immunodeficiency, eg human immunodeficiency virus infection (HIV)

- Intravenous drug abuse

- Weakened immune system due to underlying illness or medication

- Diabetes

- Chronic kidney disease

- Chronic liver disease

- Obesity

- Pregnancy

- Alcoholism

- Athlete’s foot (tinea pedis)

- Chickenpox

- Shingles

- Eczema

Many people falsely attribute an episode of cellulitis to an unseen spider bite. Documented spider bites have not led to cellulitis.

Is cellulitis contagious?

Cellulitis isn’t usually spread from person to person. Cellulitis is an infection of the deeper layers of the skin most commonly caused by bacteria that normally live on the skin’s surface. You have an increased risk of developing cellulitis if you:

- Have an injury, such as a cut, fracture, burn or scrape

- Have a skin condition, such as eczema, athlete’s foot or shingles

- Participate in contact sports, such as wrestling

- Have diabetes or a weakened immune system

- Have a chronic swelling of your arms or legs (lymphedema)

- Use intravenous drugs

However, direct person-to-person transmission of group A strep (Streptococcus pyogenes) can occur through contact with skin lesions or exposure to respiratory droplets 7. People with active infection are more likely to transmit group A strep (Streptococcus pyogenes) compared to asymptomatic carriers. Local dermatophyte (fungal) infection (e.g., athlete’s foot) may serve as portal of entry for group A strep (Streptococcus pyogenes) 2.

The spread of all types of group A strep (Streptococcus pyogenes) infection can be reduced by good hand hygiene, especially after coughing and sneezing, and respiratory etiquette (e.g., covering your cough or sneeze). Early identification and management of superficial skin lesions is also key to cellulitis prevention. Patients with recurrent cellulitis on their leg or foot should be inspected for tinea pedis and should be treated if present. Traumatic or bite wounds should be cleaned and managed appropriately (e.g., antibiotic prophylaxis, surgical debridement if indicated) to prevent secondary infections 5.

Reduce the risk of transmission

Cellulitis is spread by skin-to-skin contact or by touching infected surfaces. Stop the spread by:

- Washing your hands often.

- Bathing or showering daily.

- Do not let dressing become wet. If they do get wet they will need to be changed. Do not swim until infection clears up.

- Covering the wound with a gauze dressing (not a Band-Aid)

- Washing your bed linen, towels and clothing separately from other family members while the infection is healing.

Cellulitis may arise when skin injury or inflammation is not adequately treated.

How to clean a wound

You can look after most cuts and wounds yourself. You can:

- Stop any bleeding by holding a clean cloth or bandage on it and apply firm pressure. Use a clean towel to apply light pressure to the area until bleeding stops (this may take a few minutes). Minor cuts and scrapes usually stop bleeding on their own. Be aware that some medicines (e.g. aspirin and warfarin) will affect bleeding, and may need pressure to be applied for a longer period of time. If needed, apply gentle pressure with a clean bandage or cloth and elevate the wound until bleeding stops.

- Wash your hands well. Prior to cleaning or dressing the wound, ensure your hands are washed to prevent contamination and infection of the wound.

- Clean the wound by rinsing it with clean water and picking out any dirt (e.g. gravel) or debris with tweezers (don’t use antiseptic cream), as this will reduce the risk of infection. Keeping the wound under running tap water will reduce the risk of infection. Wash around the wound with soap.

- Dry the wound. Gently pat dry the surrounding skin with a clean pad or towel.

- Replace any skin flaps if possible. If there is a skin flap and it is still attached, gently reposition the skin flap back over the wound as much as possible using a moist cotton bud or pad.

- To help the injured skin heal, use an antibiotic ointment (e.g., Neosporin, Polysporin) or petroleum jelly to keep the wound moist. Petroleum jelly prevents the wound from drying out and forming a scab; wounds with scabs take longer to heal. This will also help prevent a scar from getting too large, deep or itchy. As long as the wound is cleaned daily, it is not necessary to use anti-bacterial ointments. However, several studies have supported the use of prophylactic topical antibiotics for minor wounds. An randomized controlled trial of 426 patients with uncomplicated wounds found significantly lower infection rates with topical bacitracin, neomycin/bacitracin/polymyxin B, or silver sulfadiazine (Silvadene) compared with topical petrolatum (5.5%, 4.5%, 12.1%, and 17.6%, respectively) 9. Certain ingredients in some ointments can cause a mild rash in some people. If a rash appears, stop using the ointment.

- Cover the wound (small wounds can be left uncovered) 10. Use a non-stick or gentle dressing and lightly bandage in place; try to avoid using tape on fragile skin to prevent further trauma on dressing removal. Dressings protect the wound by acting as a barrier to infection and absorbing wound fluid. A moist wound bed stimulates epithelial cells to migrate across the wound bed and resurface the wound 11. A dry environment leads to cell desiccation and causes scab formation, which delays wound healing. Older studies in animals and humans suggest that moist wounds had faster rates of re-epithelialization compared with dry wounds 12.

- Manage pain. Wounds can be painful, so consider pain relief while the wound heals. Talk to your doctor or pharmacist about options for pain relief.

- Change the dressing every day or whenever the bandage becomes wet or dirty.

- Get a tetanus shot. Get a tetanus shot if you haven’t had one in the past five years and the wound is deep or dirty.

- Watch for signs of infection. See a doctor if you see signs of infection on the skin or near the wound, such as redness, increasing pain, drainage, warmth or swelling.

- It’s also important to care for yourself, as this helps wounds heal faster. So eat fresh food, get some exercise, avoid smoking, and avoid drinking too much and drink plenty of water (unless you have liquid intake restrictions) to maintain supple, healthy skin.

See a doctor or nurse for a tetanus immunization within a day if you have had any cut or abrasion and any of the following apply:

- It is more than 10 years since your last tetanus shot or you can’t remember when you last had a tetanus shot 13. The Centers for Disease Control and Prevention (CDC) recommends that tetanus toxoid be administered as soon as possible to patients who have no history of tetanus immunization, who have not completed a primary series of tetanus immunization (at least three tetanus toxoid–containing vaccines), or who have not received a tetanus booster in the past 10 years.

- It is more than five years since your last tetanus shot and there was dirt in in the cut or abrasion, or the cut is deep.

- You should have the tetanus booster shot within 48 hours of the injury.

- Besides a tetanus shot, your doctor may also give you an injection of something called tetanus immune globulin, which acts fast to prevent infection 14. There is a small window of opportunity for the tetanus immune globulin to work, so don’t delay seeking medical care.

- Be aware of the first signs of tetanus infection. Also known as lockjaw, tetanus causes stiffness of the neck, difficulty swallowing, rigidity of abdominal muscles, spasms, sweating and fever. Symptoms usually begin eight days after the infection, but occur anywhere within three days to three weeks.

Cellulitis causes

Cellulitis occurs when bacteria, most commonly Streptococcus pyogenes (two thirds of cases) and Staphylococcus aureus (one third of cases), enter through a crack or break in your skin. The incidence of a more serious staphylococcus infection called methicillin-resistant Staphylococcus aureus (MRSA) is increasing.

For many people who get cellulitis, experts do not know how the bacteria get into the body. Sometimes the bacteria get into the body through openings in the skin, like an injury or surgical wound. In general, people cannot catch cellulitis from someone else; it is not contagious.

Rare causes of cellulitis include 15:

- Pseudomonas aeruginosa, usually in a puncture wound of foot or hand

- Haemophilus influenzae, in children with facial cellulitis

- Anaerobes, Eikenella, Streptococcus viridans, due to human bite

- Pasteurella multocida, due to cat or dog bite

- Vibrio vulnificus, due to salt water exposure, e.g., coral injury

- Aeromonas hydrophila from fresh or salt water exposure, e.g., following leech bites

- Erysipelothrix (erysipeloid), in butchers

Cellulitis usually occurs in skin areas that have been damaged or inflamed for other reasons, including:

- trauma, such as an insect bite, burn, abrasion or cut

- a surgical wound

- skin problems, such as eczema, psoriasis, scabies or acne

- a foreign object in the skin, such as metal or glass.

Often, it is not possible to find a cause for cellulitis.

Although cellulitis can occur anywhere on your body, the most common location is the lower leg. Bacteria are most likely to enter disrupted areas of skin, such as where you’ve had recent surgery, cuts, puncture wounds, an ulcer, athlete’s foot or dermatitis.

Animal bites can cause cellulitis. Bacteria can also enter through areas of dry, flaky skin or swollen skin.

Risk factors for developing cellulitis

Several factors put you at increased risk of cellulitis:

- Injury. Any cut, fracture, burn or scrape gives bacteria an entry point.

- Weakened immune system. Conditions that weaken your immune system — such as diabetes, leukemia and HIV/AIDS — leave you more susceptible to infections. Certain medications also can weaken your immune system.

- Skin conditions. Conditions such as eczema, athlete’s foot and shingles can cause breaks in the skin, which give bacteria an entry point.

- Chronic swelling of your arms or legs (lymphedema). This condition sometimes follows surgery.

- History of cellulitis. Having had cellulitis before makes you prone to develop it again.

- Obesity. Being overweight or obese increases your risk of developing cellulitis.

Cellulitis prevention

If your cellulitis recurs, your doctor may recommend preventive antibiotics. To help prevent cellulitis and other infections, take these precautions when you have a skin wound:

- Wash your wound daily with soap and water. Do this gently as part of your normal bathing.

- Apply a protective cream or ointment. For most surface wounds, an over-the-counter ointment (Vaseline, Polysporin, others) provides adequate protection.

- Cover your wound with a bandage. Change bandages at least daily.

- Watch for signs of infection. Redness, pain and drainage all signal possible infection and the need for medical evaluation.

People with diabetes and those with poor circulation need to take extra precautions to prevent skin injury. Good skin care measures include the following:

- Inspect your feet daily. Regularly check your feet for signs of injury so you can catch infections early.

- Moisturize your skin regularly. Lubricating your skin helps prevent cracking and peeling. Do not apply moisturizer to open sores.

- Trim your fingernails and toenails carefully. Take care not to injure the surrounding skin.

- Protect your hands and feet. Wear appropriate footwear and gloves.

- Promptly treat infections on the skin’s surface (superficial), such as athlete’s foot. Superficial skin infections can easily spread from person to person. DON’T wait to start treatment.

How to prevent recurrent episodes of cellulitis

To help prevent recurrent episodes of cellulitis — a bacterial infection in the deepest layer of skin — keep skin clean and well-moisturized. Prevent cuts and scrapes by wearing appropriate clothing and footwear, using gloves when necessary, and trimming fingernails and toenails with care.

Factors that may increase your risk of cellulitis include:

- Pre-existing skin diseases, such as athlete’s foot

- Puncture injuries, such as insect or animal bites

- Surgical incisions or pressure sores

- Immune system problem, such as diabetes

- Injuries that occur when you’re in a lake, river or ocean

- Hot tub use

Cellulitis usually makes the affected skin hot, red, swollen and painful. Your skin may look pebbled, like an orange peel. Seek prompt medical attention at the first sign of a skin infection. Treatment is usually with antibiotics. Some people who frequently develop cellulitis may benefit from long-term low-dose antibiotic treatment to prevent recurrent infections. Prophylactic antibiotics, such as oral penicillin or erythromycin oral twice daily for 4–52 weeks, or intramuscular benzathine penicillin every 2–4 weeks, should be considered in patients who have 3–4 episodes of cellulitis per year despite attempts to treat or control predisposing factors 5. This antibiotic program should be continued so long as the predisposing factors persist 5.

Cellulitis symptoms

Possible signs and symptoms of cellulitis, which usually occur on one side of the body, include:

- Redness, swelling and tenderness of skin and subcutaneous tissue underneath it that tends to expand (spread)

- Warmth of the affected skin

- Fever and chills

- Swollen glands or lymph nodes

- Pain

- Red spots

- Blisters

- Dimpled skin (peau d’orange)

- Weeping or leaking of yellow clear fluid or pus

- Erosions and ulceration

- Abscess formation

- Purpura: petechiae, ecchymoses, or hemorrhagic bullae

Cellulitis may be associated with lymphangiitis and lymphadenitis, which are due to bacteria within lymph vessels and local lymph glands. A red line tracks from the site of infection to nearby tender, swollen lymph glands.

Left untreated, cellulitis can rapidly turn into a life-threatening condition. Treatment usually includes antibiotics. In severe cases, you may need to be hospitalized and receive antibiotics through your veins (intravenously).

Cellulitis complications

The infection can spread to the rest of the body. The lymph nodes may swell and be noticed as a tender lump in the groin and armpit. You may also have fevers, sweats and vomiting.

Severe or rapidly progressive cellulitis may lead to:

- Necrotizing fasciitis (a more serious soft tissue infection recognized by severe pain, skin pallor, loss of sensation, purpura, ulceration and necrosis). Necrotizing fasciitis is an example of a deep-layer infection. It’s an extreme emergency.

- Gas gangrene

- Severe sepsis (blood poisoning)

- Infection of other organs, e.g., pneumonia, osteomyelitis, meningitis

- Endocarditis (heart valve infection).

Sepsis is recognized by fever, malaise, loss of appetite, nausea, lethargy, headache, aching muscles and joints. Serious infection leads to hypotension (low blood pressure, collapse), reduced capillary circulation, heart failure, diarrhea, gastrointestinal bleeding, renal failure and loss of consciousness.

Recurrent episodes of cellulitis may damage the lymphatic drainage system and cause chronic swelling of the affected limb.

Cellulitis diagnosis

Your doctor will likely be able to diagnose cellulitis by looking at your skin. In some cases, he or she may suggest blood tests or other tests to help rule out other conditions.

Investigations may reveal:

- Leukocytosis (raised white cell count).

- Elevated C-reactive protein (CRP)

- Causative organism, on culture of blood or of pustules, crusts, erosions or wound

Imaging may be performed. For example:

- Chest X-ray in case of heart failure or pneumonia

- Doppler ultrasound to look for blood clots (deep vein thrombosis)

- MRI in case of necrotizing fasciitis.

Cellulitis treatment

Antibiotics are used to treat the infection. Oral antibiotics may be adequate, but in the severely ill person, intravenous antibiotics will be needed to control and prevent further spread of the infection. This treatment is given in hospital or sometimes, at home by a local doctor or nurse. Your doctor also might recommend elevating the affected area, which may speed recovery.

Within three days of starting an antibiotic, let your doctor know whether the infection is responding to treatment. You’ll need to take the antibiotic for as long as your doctor directs, usually five to 10 days but possibly as long as 14 days. After successful treatment, the skin may flake or peel off as it heals. This can be itchy.

As the infection improves, you may be able to change from intravenous to oral antibiotics, which can be taken at home for a further week to 10 days. Most people respond to antibiotics in two to three days and begin to show improvement. In some cases, antibiotics are continued until all signs of infection have cleared (redness, pain and swelling), sometimes for several months.

In most cases, signs and symptoms of cellulitis disappear after a few days. You may need to be hospitalized and receive antibiotics through your veins (intravenously) if:

- Signs and symptoms don’t respond to oral antibiotics

- Signs and symptoms are extensive

- You have a high fever

In rare cases, the cellulitis may progress to a serious illness by spreading to deeper tissues. In addition to broad spectrum antibiotics, surgery is sometimes required.

Treatment should also include:

- Analgesia to reduce pain

- Adequate water/fluid intake

- Management of co-existing skin conditions like venous eczema or tinea pedis

Cellulitis antibiotics

The management of cellulitis is becoming more complicated due to rising rates of methicillin-resistant Staphylococcus aureus (MRSA) and macrolide- or erythromycin-resistant Streptococcus pyogenes.

Usually, doctors prescribe a drug that’s effective against both streptococci and staphylococci. It’s important that you take the medication as directed and finish the entire course of medication, even after you feel better.

Treatment of cellulitis with systemic illness

More severe cellulitis and systemic symptoms should be treated with fluids, intravenous antibiotics and oxygen. The choice of antibiotics depends on local protocols based on prevalent organisms and their resistance patterns, and may be altered according to culture/susceptibility reports.

- Penicillin-based antibiotics are often chosen (eg penicillin G or flucloxacillin)

- Amoxicillin and clavulanic acid provide broad-spectrum cover if unusual bacteria are suspected

- Cephalosporins are also commonly used (eg ceftriaxone, cefotaxime or cefazolin)

- Clindamycin, sulfamethoxazole/trimethoprim, doxycycline and vancomycin are used in patients with penicillin or cephalosporin allergy, or where infection with methicillin-resistant Staphylococcus aureus is suspected

- Broad-spectrum antibiotics may also include linezolid, ceftaroline, or daptomycin

Sometimes oral probenecid is added to maintain antibiotic levels in the blood.

Treatment may be switched to oral antibiotics when fever has settled, cellulitis has regressed, and CRP is reducing.

Cellulitis home treatment

Self-care at home to help ease any pain and swelling include:

- Get plenty of rest. This gives your body a chance to fight the infection.

- Raise the area of the body involved as high as possible. This will ease the pain, help drainage and reduce swelling.

- Take pain-relieving medication such as paracetamol. Check the label for how much to take and how often. The pain eases once the infection starts getting better.

- If you are not admitted to hospital, you will require a follow-up appointment with your doctor within a day or two to make sure the cellulitis is improving. This appointment is important to attend.

Management of recurrent cellulitis

Patients with recurrent cellulitis should:

- Avoid trauma, wear long sleeves and pants in high risk activities, eg gardening

- Keep skin clean and well moisturized, with nails well tended

- Avoid having blood tests taken from the affected limb

- Treat fungal infections of hands and feet early

- Keep swollen limbs elevated during rest periods to aid lymphatic circulation. Those with chronic lymphedema may benefit from compression garments.

Patients with 2 or more episodes of cellulitis may benefit from chronic suppressive antibiotic treatment with low-dose penicillin V or erythromycin, for one to two years.

Impetigo

Impetigo also called “school sores” or pyoderma, is a highly contagious skin infection caused by bacteria 16. Impetigo is characterized by pustules and honey-colored crusted erosions (“school sores”). More than 90 percent of impetigo cases are caused by Staphylococcus aureus or “golden staph” bacteria, while the rest are caused by Streptococcus pyogenes (group A beta-hemolytic Streptococcus) bacteria (which also are responsible for “strep throat” and “scarlet fever“) 17, 18, 19. Generally, those who are affected are carriers of these bacteria, Staphylococcus aureus and Streptococcus pyogenes, meaning that their nostrils are colonized by the bacteria. If Staphylococcus aureus bacteria are to blame, the infection may cause blisters filled with clear fluid (bullous impetigo). These can break easily, leaving a raw, glistening area that soon forms a scab with a honey colored crust. By contrast, infections with Streptococcus pyogenes (group A beta-hemolytic Streptococcus) bacteria usually are not associated with blisters (non bullous impetigo or impetigo contagiosa), but they do cause crusts over larger sores and ulcers. Methicillin-resistant Staphylococcus aureus (MRSA) bacteria is also becoming an important cause of impetigo.

Impetigo is most common in children between the ages of two and six; however, adults can be affected by impetigo too. Impetigo usually starts when bacteria get into a break in the skin, such as a cut, scratch, or insect bite.

Young children often develop impetigo around the nose or mouth as a result of colonization of the nostrils, but the disease can occur anywhere – particularly if the skin barrier is disrupted in another part of the body such as with eczema or a dermatitis.

Symptoms start with red or pimple-like sores surrounded by red skin. These sores can be anywhere, but usually they occur on your face (around the nose, mouth, and ears), arms and legs. The sores fill with pus, then break open after a few days and form a thick crust. They are often itchy, but scratching them can spread the sores to other parts of their body. Impetigo can spread to anyone who touches infected skin or items that have been touched by infected skin (such as clothing, towels, and bed linens).

In the United States, impetigo is more common in the summer 20. There are more than 3 million cases of impetigo in the United States every year. Doctors typically see impetigo with kids 2 to 6 years old, probably because they get more cuts and scrapes and scratch more. The World Health Organization (WHO) estimates that 111 million children in less developed countries have streptococcal impetigo at any one time 21. Higher rates of impetigo are found in crowded and impoverished settings, in warm and humid conditions, and among populations with poor hygiene.

Complications related to impetigo can include deeper skin infection (cellulitis), meningitis, or a kidney inflammation (post streptococcal glomerulonephritis, which is not prevented by treatment) with few people going to develop kidney failure 22. The kidney dysfunction appears 7-14 days after the infection 22. The transient blood in urine (hematuria) and protein in urine (proteinuria) may last a few weeks or months. Other complications include septic arthritis, scarlet fever, sepsis, and staphylococcal scalded skin syndrome.

Impetigo is contagious and it can spread by contact with sores or nasal discharge from an infected person. You can treat impetigo with antibiotics.

Your doctor will look at your skin to determine if you have impetigo. Your doctor may take a sample of bacteria from your skin to grow in the lab. This can help determine if MRSA is the cause. Specific antibiotics are needed to treat this type of bacteria.

Impetigo will generally resolve on its own in a matter of weeks, but the use of topical or oral antibiotics prescribed by your doctor can hasten resolution of the infection.

Who gets impetigo?

Impetigo is most common in children (especially boys), but may also affect adults if they have low immunity to the bacteria. It is prevalent worldwide. Peak onset is during summer and it is more prevalent in developing countries.

The following factors predispose to impetigo.

- Atopic dermatitis or eczema

- Scabies

- Skin trauma: chickenpox, insect bite, abrasion, laceration, thermal burn, dermatitis, surgical wound.

How does impetigo spread?

Streptococcal impetigo is most commonly spread through direct contact with other people with impetigo, including through contact with drainage from impetigo lesions. Lesions can be spread (by fingers and clothing) to other parts of the body. People with impetigo are much more likely to transmit the bacteria than asymptomatic carriers. Crowding, such as found in schools and daycare centers, increases the risk of disease spread from person to person.

Humans are the primary reservoir for Streptococcus pyogenes (group A beta-hemolytic Streptococcus). There is no evidence to indicate that pets can transmit the bacteria to humans.

What is the incubation period for impetigo?

The incubation period of impetigo, from colonization of the skin to development of the characteristic lesions, is about 10 days 20. It is important to note not everyone who becomes colonized will go on to develop impetigo.

How long is impetigo contagious?

Impetigo is contagious until the rash clears, or until at least two days of antibiotics have been given and there is evidence of improvement 17. Your child should avoid close contact with other children during this period, and you should avoid touching the rash. If you or other family members do come in contact with it, wash your hands and the exposed site thoroughly with soap and water. Also, keep the infected child’s washcloths and towels separate from those of other family members.

Types of impetigo

The three types of impetigo are non-bullous (crusted), bullous (large blisters) and ecthyma (ulcers):

Non-bullous impetigo

Non-bullous also known as crusted impetigo or impetigo contagiosa is most common. Non-bullous impetigo is caused by either Staphylococcus aureus, Streptococcus pyogenes, or both bacteria conjointly. It begins as tiny blisters that eventually burst and leave small wet patches of red skin that may weep fluid. Gradually, a yellowish-brown or tan crust covers the area, making it look like it has been coated with honey or brown sugar.

Intact skin is usually resistant to colonization from bacteria. Disruption in skin integrity allows for invasion of bacteria via the interrupted surface.

Bullous impetigo

Bullous impetigo causes larger fluid-containing blisters that look clear, then cloudy. Bullous impetigo is caused by Staphylococcus aureus bacteria which produces exfoliative toxins (exfoliatins A and B). Exfoliative toxins target intracellular adhesion molecules (desmoglein – 1) present in the epidermal granular layer. Results in dissociation of epidermal cells which causes blister formation. These blisters are more likely to stay longer on the skin without bursting.

Bullous impetigo can occur on areas of intact skin.

Ecthyma or ulcerated impetigo

Ecthyma or ulcerated impetigo is usually due to Streptococcus pyogenes, but co-infection with Staphylococcus aureus may occur. Ecthyma is a deep form of impetigo, as the same bacteria causing the infection are involved. Ecthyma causes deeper erosions of the skin into the dermis. Ecthyma is a skin infection characterized by crusted sores beneath which ulcers form.

Impetigo causes

Impetigo is caused by Streptococcus pyogenes (group A beta-hemolytic Streptococcus) or Staphylococcus aureus (staph) bacteria 18, 19. Methicillin-resistant staph aureus (MRSA) is becoming a common cause. Impetigo can be “bullous impetigo” or “non-bullous impetigo”. Toxin-producing Staphylococcus aureus cause bullous impetigo, Streptococcus pyogenes (group A beta-hemolytic Streptococcus) or both cause non-bullous impetigo, which is also called “impetigo contagiosa.”

Streptococcus pyogenes (group A beta-hemolytic Streptococcus) are Gram-positive cocci that grow in chains. They exhibit beta-hemolysis (complete hemolysis) when grown on blood agar plates. Streptococcus pyogenes belong to group A in the Lancefield classification system for beta-hemolytic Streptococcus, and thus are also called group A streptococci.

Skin normally has many types of bacteria on it; Streptococcus pyogenes (group A beta-hemolytic Streptococcus) and Staphylococcus aureus, intermittently colonizing the nasal, armpit, throat, or perineal areas 23, 24. When there is a break in the skin, the bacteria can enter the body and grow there. This causes inflammation and infection. Breaks in the skin may occur from injury or trauma to the skin or from insect (e.g., infected mosquito bites), animal, or human bites 25, 26. However, impetigo may also occur on skin where there is no visible break.

Many bacteria inhabit healthy skin; some types, such as Streptococcus pyogenes (group A beta-hemolytic Streptococcus) or Staphylococcus aureus (staph) can lead to infection of susceptible skin 24. Other factors that predispose to impetigo are skin trauma; hot, humid climates; poor hygiene; day care settings; crowding; malnutrition; and diabetes mellitus or other medical comorbidities 23, 24. Autoinoculation via fingers, towels, or clothing often leads to the formation of satellite lesions in adjacent areas 24. The highly contagious nature of impetigo also allows spread from patients to close contacts. Although impetigo is considered a self-limited infection, antibiotic treatment is often initiated for a quicker cure and to prevent the spread to others 23. This can help decrease the number of school and work days lost 24. Hygienic practices such as cleaning minor injuries with soap and water, handwashing, regular bathing, and avoiding contact with infected children can help prevent infection 27.

Impetigo is most common in children who live in unhealthy conditions.

In adults, it may occur following another skin problem. It may also develop after a cold or other virus.

Impetigo can spread to others. You can catch the infection from someone who has it if the fluid that oozes from their skin blisters touches an open area on your skin.

Because impetigo spreads by skin-to-skin contact, there often are small outbreaks within a family or a classroom. Avoid touching objects that someone with impetigo has used, such as utensils, towels, sheets, clothing and toys. If you have impetigo, keep your fingernails short so the bacteria can’t live under your nails and spread. Also, don’t scratch the sores.

See your health care provider if the symptoms don’t go away or if there are signs the infection has worsened, such as fever, pain, or increased swelling.

Risk factors for impetigo

Factors that increase the risk of impetigo include:

- Age. Impetigo most commonly occurs in children ages 2 to 5.

- Poor personal hygiene. Lack of proper handwashing, body washing, and facial cleanliness can increase someone’s risk of getting impetigo.

- People with weakened immune system or immunosuppressed (eg, diabetes, neutropenia, immunosuppressive medication, cancer, HIV and AIDS)

- Crowded conditions. Impetigo spreads easily in schools and child care settings. Close contact with another person with impetigo is the most common risk factor for infection.

- Warm, humid weather. Impetigo infections are more common in areas with hot, humid summers and mild winters (subtropics), or wet and dry seasons (tropics).

- Certain sports. Participation in sports that involve skin-to-skin contact, such as football or wrestling, increases your risk of developing impetigo.

- Skin trauma. The bacteria that cause impetigo often enter your skin through a small skin injury, thermal burns, abrasions, insect bite or rash.

- Skin conditions such as atopic dermatitis, contact dermatitis and chickenpox

- People with scabies infection are at increased risk for impetigo 28, 29.

Adults and people with diabetes or a weakened immune system are more likely to develop ecthyma. Ecthyma is a deep form of impetigo, as the same bacteria causing the infection are involved. Ecthyma causes deeper erosions of the skin into the dermis. Ecthyma is a skin infection characterized by crusted sores beneath which ulcers form.

Impetigo prevention

The bacteria that cause impetigo thrive in breaks in the skin. The best ways to prevent impetigo rash are to keep your child’s fingernails clipped and clean and to teach him not to scratch minor skin irritations. When he does have a scrape, cleanse it with soap and water, and apply an antibiotic cream or ointment. Be careful not to use washcloths or towels that have been used by someone else who has an active skin infection.

When certain types of strep bacteria cause impetigo, a rare but serious complication called glomerulonephritis can develop. This disease injures the kidney and may cause high blood pressure and blood to pass in the urine. Therefore, if you notice any blood or dark brown color in your child’s urine, let your pediatrician know so he can evaluate it and order further tests if needed.

Prevent the spread of impetigo.

- If you have impetigo, always use a clean washcloth and towel each time you wash.

- DO NOT share towels, clothing, razors, and other personal care products with anyone.

- Avoid touching blisters that are oozing.

- Wash your hands thoroughly after touching infected skin.

Keep your skin clean to prevent getting the infection. Wash minor cuts and scrapes well with soap and clean water. You can use a mild antibacterial soap.

Impetigo symptoms

Symptoms of impetigo are:

- One or many blisters that are filled with pus and easy to pop. In infants, the skin is reddish or raw-looking where a blister has broken.

- Blisters that itch, are filled with yellow or honey-colored fluid, and ooze and crust over. Rash that may begin as a single spot, but spreads to other areas with scratching.

- Skin sores on the face, lips, arms, or legs that spread to other areas.

- Swollen lymph nodes near the infection.

- Patches of impetigo on the body (in children).

In general, impetigo is a mild infection that can occur anywhere on the body. Impetigo most often affects exposed skin, such as:

- Around the nose and mouth

- On the arms or legs

Impetigo symptoms include red, itchy sores that break open and leak a clear fluid or pus for a few days. Next, a crusty yellow or “honey-colored” scab forms over the sore, which then heals without leaving a scar.

Primary impetigo mainly affects exposed areas such as the face and hands, but may also affect trunk, perineum and other body sites. It presents with single or multiple, irregular crops of irritable superficial plaques. These extend as they heal, forming annular or arcuate lesions.

Although many children are otherwise well, lymphadenopathy (enlarged lymph gland), mild fever and malaise may occur.

Figure 4. Impetigo on nose

Figure 5. Impetigo on face

Nonbullous impetigo

Nonbullous impetigo starts as a pink macule that evolves into a vesicle or pustule. Pustule or vesicle ruptures releasing serous contents which dries leaving a typical honey-colored crust. There’s minimal or no surrounding redness (erythema). Can spread rapidly with satellite lesions due to autoinoculation. “Kissing lesions” arise where two skin surfaces are in contact. People with non-bullous impetigo are typically otherwise well; they may experience some itching and regional enlarged lymph node (lymphadenopathy).

Non-bullous impetigo most commonly found on the face or extremities but skin on any part of the body can be involved.

Untreated nonbullous impetigo usually resolves within 2 to 4 weeks without scarring.

Bullous impetigo

Bullous impetigo presents with small vesicles that evolve quickly into flaccid transparent superficial, small or large thin roofed bullae which tend to spontaneously rupture and ooze yellow fluid leaving a scaley rim (collarette). It heals without scarring. People with bullous impetigo are more likely to have systemic symptoms of malaise, fever, and enlarged lymph node (lymphadenopathy).

Bullous impetigo is usually found on the face, trunk, extremities, buttocks, and perineal regions. Can spread distally due to autoinoculation.

Ecthyma

Ecthyma is a deep form of impetigo, as the same bacteria causing the infection are involved. Ecthyma causes deeper erosions of the skin into the dermis. Ecthyma starts as nonbullous impetigo but develops into a punched-out necrotic ulcer. This heals slowly, leaving a scar.

Streptococcus pyogenes and Staphylococcus aureus are the bacteria responsible for ecthyma.

Impetigo complications

Impetigo is usually a self-limited condition, and rarely, complications can occur after impetigo. These include cellulitis (nonbullous form), septicemia, osteomyelitis, septic arthritis, lymphangitis, lymphadenitis, guttate psoriasis, staphylococcal scalded skin syndrome, and acute poststreptococcal glomerulonephritis, with post streptococcal glomerulonephritis being the most serious 30. Post streptococcal glomerulonephritis is thought to be the result of an immune response that is triggered by Streptococcus pyogenes (group A beta-hemolytic Streptococcus) infection. The number of possible causes, incidence, and clinical severity of acute post streptococcal glomerulonephritis have decreased, because the causative organism of impetigo has shifted from Streptococcus pyogenes (group A beta-hemolytic Streptococcus) to Staphylococcus aureus 31. Most cases of poststreptococcal glomerulonephritis in the United States are associated with pharyngitis. The strains of Streptococcus pyogenes (group A beta-hemolytic Streptococcus) implicated in impetigo are thought to have minimal nephritogenic potential 31. There are no data to indicate that antibiotic treatment of impetigo has any effect on preventing the development of acute poststreptococcal glomerulonephritis, which can occur in up to 5% of patients with nonbullous impetigo 32, 33, 3, 34. Rheumatic fever does not appear to be a complication of impetigo 3.

Impetigo may lead to:

- Spread of the infection to other parts of the body (common)

- Kidney inflammation or failure (post-streptococcal glomerulonephritis) (rare). Acute kidney condition following infection with Streptococcus pyogenes (group A streptococcus). This is due to a type III hypersensitivity reaction and presents 2–6 weeks post-skin infection.

- Cellulitis. This potentially serious infection affects the tissues underlying your skin and eventually may spread to your lymph nodes and bloodstream. Untreated cellulitis can quickly become life-threatening.

- Wider spread infection: lymphangitis, and bacteremia.

- Staphylococcal scalded skin syndrome.

- Scarlet fever.

- Streptococcal toxic shock syndrome: a rare complication causing diffuse erythematous rash, hypotension, and pyrexia.

- Postinflammatory pigmentation.

- Permanent skin damage and scarring, particularly with ecthyma (very rare)

Soft tissue infection

The bacteria causing impetigo can become invasive, leading to cellulitis and lymphangitis; subsequent bacteremia might result in osteomyelitis, septic arthritis or pneumonia.

Staphylococcal scalded skin syndrome

In infants under 6 years of age or adults with renal insufficiency, localized bullous impetigo due to certain Staphylococcal serotypes can lead to a sick child with generalized staphylococcal scalded skin syndrome. Superficial crusting then tender cutaneous denudation on face, in skin folds, and elsewhere is due to circulating exfoliatin/epidermolysin, rather than direct skin infection. It does not scar.

Toxic shock syndrome

Post-streptococcal glomerulonephritis

Group A streptococcal infection may rarely lead to acute post-streptococcal glomerulonephritis 3–6 weeks after the skin infection. It is associated with anti-DNase B and antistreptolysin O (ASO) antibodies.

Rheumatic fever

Group A streptococcal skin infections have rarely been linked to cases of rheumatic fever and rheumatic heart disease. It is thought that this occurs because strains of group A streptococci usually found on the skin have moved to the throat (the more usual site for rheumatic fever-associated infection).

Impetigo diagnosis

Impetigo is usually diagnosed clinically but can be confirmed by bacterial swabs sent for microscopy (Gram positive cocci are observed), culture and sensitivity.

Blood count may reveal neutrophil leucocytosis when impetigo is widespread.

Skin biopsy is rarely necessary. Histological features are characteristic.

Non-bullous impetigo

- Gram-positive cocci

- Intraepidermal neutrophilic pustules,

- Dense inflammatory infiltrate in upper dermis

Bullous impetigo

- Split through granular layer of epidermis without inflammation or bacteria

- Acantholytic cells

- Minimal inflammatory infiltrate in upper dermis

- Resembles pemphigus foliaceus

Ecthyma

- Full thickness skin ulceration

- Gram stain shows cocci within dermis

Impetigo treatment

Impetigo needs to be treated with antibiotics, either topically (antibiotics rubbed onto the sores) or by mouth (oral antibiotics), and your doctor may order a culture in the lab to determine which bacteria are causing the rash. Gram stain and culture of the pus or exudates from skin lesions of impetigo and ecthyma are recommended to help identify whether Staphylococcus aureus and/or a Streptococcus pyogenes (group A beta-hemolytic Streptococcus) is the cause 33.

Make sure your child takes the medication for the full prescribed course or the impetigo could return.

- When it just affects a small area of the skin (and especially if it’s the non-bullous form), impetigo is treated with antibiotic ointment. Treatment of bullous and nonbullous impetigo should be with either mupirocin or retapamulin twice daily for 5 days 33.

- If the infection has spread to other areas of the body or the antibiotic ointment isn’t working, the doctor may prescribe an antibiotic pill or liquid to be taken for 7–10 days. Oral antibiotic therapy for ecthyma or impetigo should be a 7-day regimen with an agent active against Staphylococcus aureus unless cultures yield streptococci alone (when oral penicillin is the recommended agent) 33. Because Staphylococcus aureus isolates from impetigo and ecthyma are usually methicillin susceptible, dicloxacillin or cephalexin is recommended. When MRSA is suspected or confirmed, doxycycline, clindamycin, or sulfamethoxazole-trimethoprim (SMX-TMP) is recommended 33.

There is no over-the-counter (OTC) treatment for impetigo 35.

Quality evidence-based research for the most effective treatment of impetigo is lacking 36. In 2012, an updated Cochrane review on impetigo interventions evaluated 68 randomized controlled trials, including 26 on oral treatments and 24 on topical treatments. There was no clear evidence as to which intervention is most effective 37. Topical antibiotics are more effective than placebo and preferable to oral antibiotics for limited impetigo 36. Systemic antibiotics are often reserved for more generalized or severe infections in which topical therapy is not practical. Clinicians sometimes may choose both topical and systemic therapy 37. The ideal treatment should be effective, be inexpensive, have limited adverse effects, and should not promote bacterial resistance 38.

Untreated, impetigo often clears up on its own after a few days or weeks 39. The key is to keep the infected area clean with soap and water and not to scratch it. The downside of not treating impetigo is that some people might develop more lesions that spread to other areas of their body.

And you can infect others. To spread impetigo, you need fairly close contact — not casual contact — with the infected person or the objects they touched. Avoid spreading impetigo to other people or other parts of your body by:

- Cleaning the infected areas with soap and water (DO NOT scrub).

- Loosely covering scabs and sores until they heal.

- Gently removing crusty scabs.

- Washing your hands with soap and water after touching infected areas or infected persons.

- To prevent impetigo from spreading among family members, make sure everyone uses their own clothing, sheets, razors, soaps, and towels. Separate the bed linens, towels, and clothing of anyone with impetigo, and wash them in hot water. Keep the surfaces of your kitchen and household clean.

Table 1. Topical antibiotics for impetigo

| Medication | Instructions | Cost* |

|---|---|---|

| Fusidic acid 2% ointment† | Apply to affected skin three times daily for seven to 12 days | Available in Canada and Europe |

| Mupirocin 2% cream (Bactroban)‡ | Apply to affected skin three times daily for seven to 10 days; reevaluate after three to five days if no clinical response Approved for use in persons older than three months | 15-g tube: $48 ($89) 30-g tube: $50 ($144) |

| Mupirocin 2% ointment‡ | Apply to affected skin three times daily for seven to 14 days Dosing in children is same as adults Approved for use in persons older than two months | 22-g tube: $14 ($103) |

| Retapamulin 1% ointment (Altabax)§ | Apply to affected skin twice daily for five days Total treatment area should not exceed 100 cm2 in adults or 2% of total body surface area in children Approved for use in persons nine months or older | 15-g tube: NA ($130) 30-g tube: NA ($245) |

Footnotes: NA = not available

*Estimated retail price

† Coverage for Staphylococcus aureus (methicillin-susceptible) and streptococcus

‡ Coverage for Staphylococcus aureus (methicillin-susceptible) and streptococcus. Mupirocin resistant streptococcus has now been documented.

§ First member of the pleuromutilin class of antibiotics. Coverage for Staphylococcus aureus (methicillin-susceptible) and streptococcus.

[Source 40 ]Table 2. Oral antibiotics for impetigo

| Drug | Adult seven-day dose | Cost (for a typical course of treatment)* | Children seven-day dose | Cost* |

|---|---|---|---|---|

| Amoxicillin/clavulanate (Augmentin)† | 875/125 mg every 12 hours | $19 ($193) | Younger than three months: 30 mg per kg per day Three months or older: 25 to 45 mg per kg per day for those weighing less than 40 kg (88 lb); 875/125 mg every 12 hours for those weighing 40 kg or more Based on mg per kg per day of the amoxicillin component in divided doses every 12 hours | 1 bottle, 400/57 mg per 5 mL (100-mL oral suspension): $30 ($125) |

| Cephalexin (Keflex) | 250 mg every six hours or 500 mg every 12 hours | $5 ($90) | 25 to 50 mg per kg per day in divided doses every six to 12 hours | 1 bottle, 250 mg per 5 mL (100-mL oral suspension): $14 (NA) |

| Clindamycin‡ | 300 to 600 mg every six to eight hours | $18 ($200) | 10 to 25 mg per kg per day in divided doses every six to eight hours | 1 bottle, 75 mg per 5 mL (100-mL oral solution): $47 (pricing varies by region) |

| Dicloxacillin | 250 mg every six hours | $14 (NA) | 12.5 to 25 mg per kg per day in divided doses every six hours | See adult pricing: no liquid formulation available |

| Doxycycline§ | 50 to 100 mg every 12 hours | $15 ($95) | 2.2 to 4.4 mg per kg per day in divided doses every 12 hours Not recommend in children younger than eight years | 1 bottle, 25 mg per 5 mL (60-mL oral suspension): $20 (pricing varies by region) |

| Minocycline (Minocin)§ | 100 mg every 12 hours | $36 ($185) | Loading dose of 4 mg per kg for first dose (maximum dose of 200 mg), then 4 mg per kg per day in divided doses every 12 hours Maximum of 400 mg per day Not recommend in children younger than eight years | See adult pricing: no liquid formulation available |

| Trimethoprim/sulfamethoxazole§ | 160/800 mg every 12 hours | $4 (NA) | 8 to 10 mg per kg per day based on the trimethoprim component in divided doses every 12 hours | 1 bottle, 40/200 mg per 5 mL (100-mL oral suspension): $4 (pricing varies by region) |

Footnote: Because of emerging resistance, penicillin and erythromycin are no longer recommended treatments.

NA = not available

* Estimated retail price based on information obtained at http://www.goodrx.com. Generic price listed first; brand listed in parentheses.

† Good coverage for Staphylococcus aureus (methicillin-susceptible) and streptococcus.

‡ If methicillin-resistant Staphylococcus aureus (MRSA) is suspected or proven.

§ If methicillin-resistant Staphylococcus aureus (MRSA) is suspected or proven. There is no activity against streptococcus.

[Source 40 ]Home remedies for impetigo

Topical disinfectants

There are some studies on the benefits of nonantibiotic treatments, such as disinfectant soaps, but they lack statistical power 36. Disinfectants appear to be less effective than topical antibiotics and are not recommended 37. Studies comparing hexachlorophene (not available in the United States) with bacitracin and hydrogen peroxide with topical fusidic acid found the topical antibiotic to be more effective 41.

Natural therapies

The evidence is insufficient to recommend or dismiss popular herbal treatments for impetigo 42. Natural remedies such as tea tree oil; tea effusions; olive, garlic, and coconut oils; and Manuka honey have been anecdotally successful. The fact that impetigo is self-limited means that many “cures” could appear to be helpful without being superior to placebo. In one study, tea leaf ointment and oral cephalexin (Keflex) were similarly effective, with a cure rate of 81% vs. 79% 43. Tea tree oil (derived from Melaleuca alternifolia) appeared to be equivalent to mupirocin 2% for topical decolonization of MRSA 44.

Impetigo prognosis

Without treatment, impetigo heals in 14-21 days 22. About 20% of cases resolve spontaneously. Scarring is rare but some patients may develop pigmentation changes. Some patients may develop ecthyma. With treatment, cure occurs within 10 days 22. Neonates may develop meningitis. A rare complication is acute post streptococcal glomerulonephritis, which occurs 2-3 weeks after the skin infection 22.

Fungal skin infections

Fungal infections of the skin are also known as ‘mycoses’. They are common and generally mild. However, in very sick or otherwise immune suppressed people, fungi can sometimes cause severe disease.

Fungi usually make their homes in moist areas of the body where skin surfaces meet: between the toes, in the genital area, and under the breasts. Common fungal skin infections are caused by yeasts (such as Candida or Malassezia furfur) or dermatophytes, such as Epidermophyton, Microsporum, and Trichophyton.

Many fungi live only in the topmost layer of the epidermis (stratum corneum) and do not penetrate deeper. Obese people are more likely to get these infections because they have excessive skinfolds, especially if the skin within a skinfold becomes irritated and broken down (intertrigo). People with diabetes tend to be more susceptible to fungal infections as well.

Strangely, fungal infections on one part of the body can cause rashes on other parts of the body that are not infected. For example, a fungal infection on the foot may cause an itchy, bumpy rash on the fingers. These eruptions (dermatophytids, or identity or id reactions) are allergic reactions to the fungus. They do not result from touching the infected area.

- Superficial fungal infections. These affect the outer layers of the skin, the nails and hair. The main groups of fungi causing superficial fungal infections are:

- Dermatophytes (tinea)

- Yeasts: Candida, including non-albicans candida species, Malassezia, Piedra. Yeasts form a subtype of fungus characterized by clusters of round or oval cells. These bud out similar cells from their surface to divide and propagate. In some circumstances, they form a chain of cells called a pseudomycelium.

- Molds.

- Subcutaneous fungal infections. These involve the deeper layers of the skin (the dermis, subcutaneous tissue and even bone). The causative organisms live in the soil on rotting vegetation. They can get pricked into the skin as a result of an injury but usually stay localized at the site of implantation. Deeper skin infections include:

Fungus that cause skin infection

Candida

- diaper dermatitis (diaper rash)

- Non-albicans candida infections

- Oral candidiasis (oral thrush)

- Vulvovaginal candidiasis (vaginal thrush)

- Candida intertrigo (skin fold infection)

- Paronychia (nail fold infections)

- Chronic mucocutaneous candidiasis

- Cyclic vulvovaginitis (cyclical symptoms due to vulvovaginal candidiasis)

Malassezia

- Pityriasis versicolor (tinea versicolor)

- Malassezia (pityrosporum) folliculitis

- Seborrheic dermatitis

Dermatophyte infections

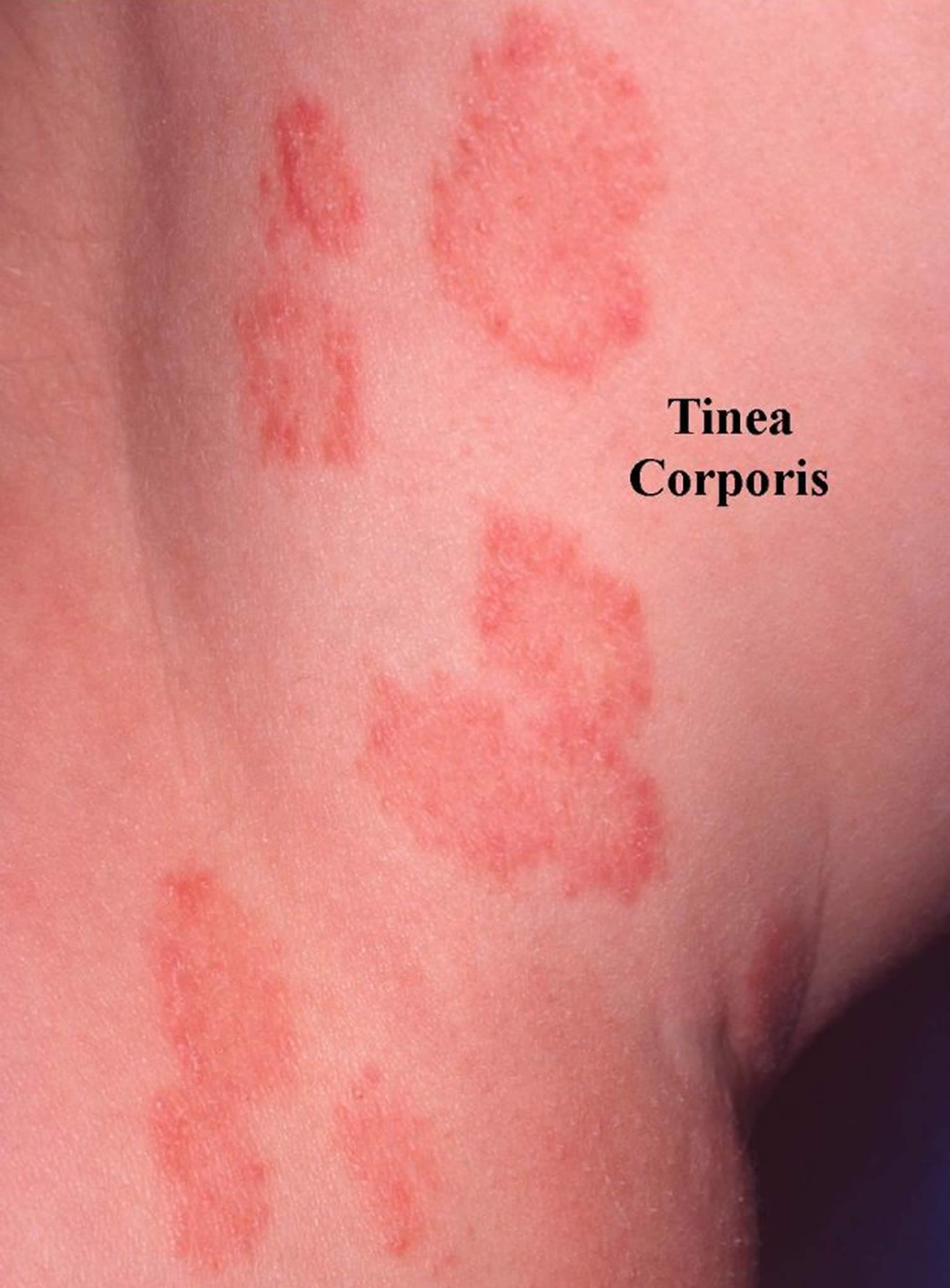

- Tinea infections. Tinea is a skin infection with a dermatophyte ringworm fungus. Depending on which part of the body is affected, it is given a specific name.

- Tinea barbae (fungal infection of the beard)

- Tinea capitis (fungal infection of the scalp)

- Tinea corporis (fungal infection of the trunk and limbs)

- Tinea cruris (fungal infection of the groin)

- Tinea faciei (fungal infection of the face)

- Tinea incognito (steroid-treated fungal infection)

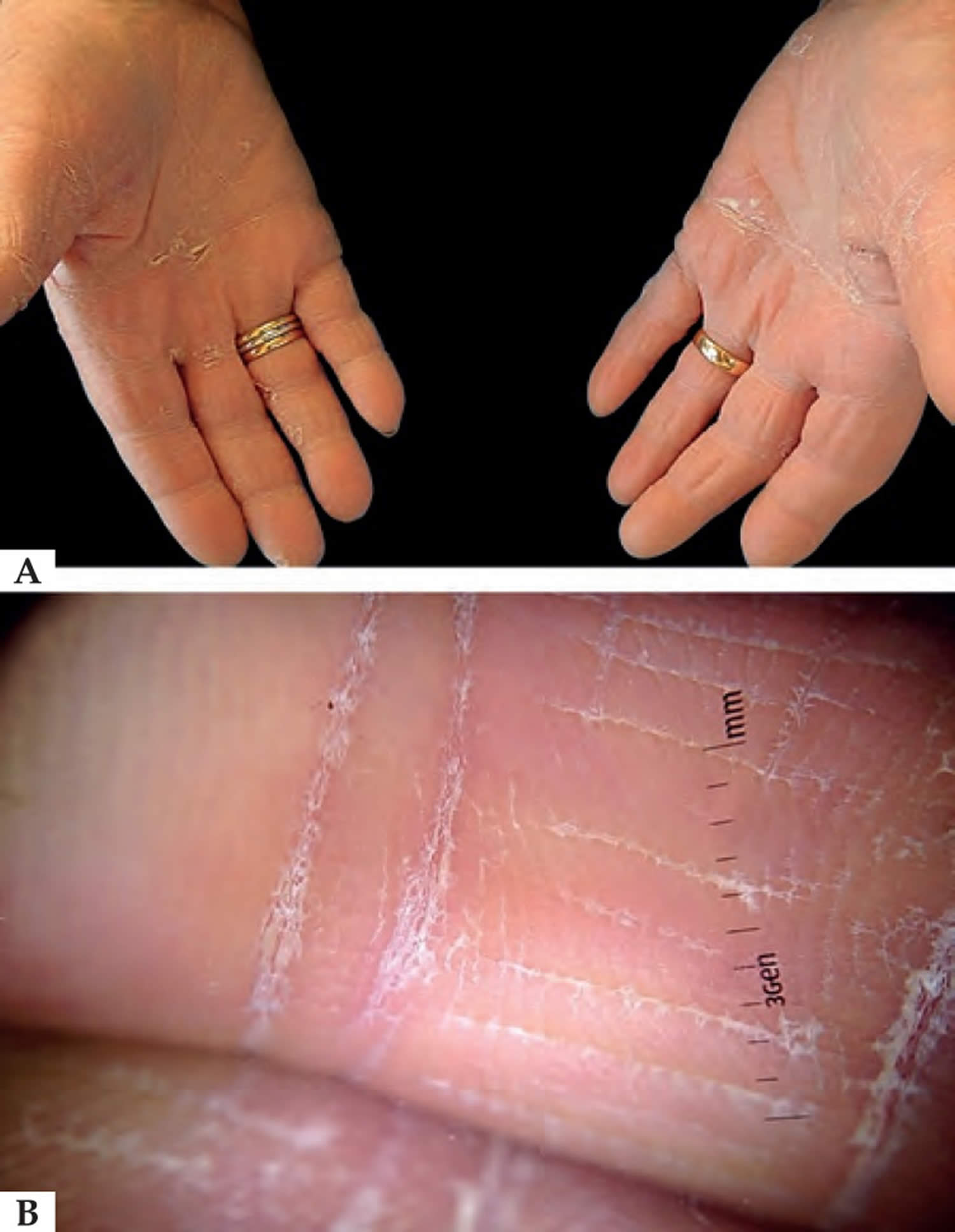

- Tinea manuum (fungal infection of the hand)

- Tinea pedis (fungal infection of the foot)

- Tinea unguium (onychomycosis, fungal nail infection)

- Majocchi granuloma (deep fungal infection of hair follicles)

- Kerion (fungal abscess)

- Dermatophytide (id reactions) dermatitis in reaction to tinea infection

Deep fungal infections

Systemic mycoses may result from breathing in the spores of fungi, which live in the soil or rotting vegetation, or present as an opportunistic disease in immunocompromised individuals.

- Aspergillosis

- Blastomycosis

- Cryptococcosis

- Chromoblastomycosis

- Histoplasmosis

- Mycetoma

- Sporotrichosis

- Sporotrichoid spread

- Systemic mycoses

- Talaromycosis

- Zygomycosis

Fungal skin infection diagnosis

Your doctor may suspect a fungal infection when they see a red, irritated, or scaly rash in one of the commonly affected areas.

Your doctor can usually confirm the diagnosis of a fungal skin infection by scraping off a small amount of skin and having it examined under a microscope or placed in a culture medium where the specific fungus can grow and be identified.

Fungal skin infection treatment

Fungal skin infections are typically treated with antifungal drugs, usually with antifungal drugs that are applied directly to the affected area (called topical drugs). Topical drugs may include creams, gels, lotions, solutions, or shampoos. Antifungal drugs may also be taken by mouth.

Many antifungal medications are suitable for both dermatophyte and yeast infections. Others are more specific to one or the other type of fungus. Those unsuitable for dermatophyte fungal infections are marked with an asterisk (*) in the list that follows.

- Whitfield ointment (3% salicylic acid, 6% benzoic acid in petrolatum)

- Undecylenic alkanolamide

- Ciclopirox olamine

- Polyenes *

- Nystatin

- Imidazoles

- Bifonazole

- Clotrimazole

- Econazole

- Efinaconazole

- Ketoconazole

- Luliconazole

- Miconazole

- Sulconazole

- Tioconazole

- Allylamine

- Terbinafine

- Thiocarbamates

- Tolciclate

- Tolnaftate

- Benzoxaborole

- Tavaborole

Topical antifungals can be obtained over the counter without a doctor’s prescription. They are generally applied to the affected area twice daily for two to four weeks, including a margin of several centimetres of normal skin. Treatment should continue for one or two weeks after the last visible rash has cleared. They can often cure a localized infection, although recurrence is common so repeated treatment is often necessary.

In addition to antifungal drugs, people may use measures to keep the affected areas dry, such as applying powders or wearing open-toed shoes.

Corticosteroids can help relieve inflammation and itching caused by some infections, but these should be used only when prescribed by a doctor.

Oral antifungal medications may be required for a fungal infection if:

- It is extensive or severe

- It resists topical antifungal therapy

- It affects hair-bearing areas (tinea capitis and tinea barbae).

Scalp antifungal agents

Antifungal shampoos are mainly used to treat dandruff or seborrheic dermatitis but are used as an adjunct for tinea capitis and scalp psoriasis. The most effective ingredients are ketoconazole, miconazole and ciclopirox (Stieprox® liquid), but many other shampoos marketed for dandruff have antifungal properties.

Nail fold antifungal agents

There are many antiseptic and antifungal preparations to control nail fold fungal infections (paronychia). They should be applied two or three times daily for several months.

- Clotrimazole solution

- Econazole solution

- Miconazole

- Sulfacetamide 15% in spirit

Nail plate antifungal agents

Distal onychomycosis can be treated with an antifungal lacquer applied once or twice weekly. The medication should be applied to the surface of the cleaned nail plate after it has been roughened using an emery board. Extra lacquer should be applied under the edge of the nail.

Available preparations are:

- Amorolfine

- Ciclopirox

- Bifonazole cream + urea ointment

- Efinaconazole solution

- Tavaborole solution.

These can be expected to reduce and sometimes cure the infection, provided that:

- No more than 50% of the nail plate is infected

- The growing part of the nail plate (the matrix) is not involved